Abstract

Introduction

Initiation of injectable therapies in type 2 diabetes (T2D) is often delayed, however the reasons why are not fully understood.

Methods

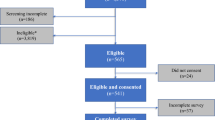

A mixed methods study performed in sequential phases. Phase 1: focus groups with people with T2D (injectable naïve [n = 12] and experienced [n = 5]) and healthcare professionals (HCPs; nurses [n = 5] and general practitioners (GPs) [n = 7]) to understand their perceptions of factors affecting initiation of injectables. Phase 2: video-captured GP consultations (n = 18) with actor-portrayed patient scenarios requiring T2D treatment escalation to observe the initiation in the clinical setting. Phase 3: HCP surveys (n = 87) to explore external validity of the themes identified in a larger sample.

Results

Focus groups identified patients’ barriers to initiation; fear, lack of knowledge and misconceptions about diabetes and treatment aims, concerns regarding lifestyle restrictions and social stigma, and feelings of failure. Facilitators included education, good communication, clinician support and competence. HCP barriers included concerns about weight gain and hypoglycaemia, and limited consultation time. In simulated consultations, GPs performed high-quality consultations and recognised the need for injectable initiation in 9/12 consultations where this was the expert recommended option but did not provide support for initiation themselves. Survey results demonstrated HCPs believe injectable initiation should be performed in primary care, although many practitioners reported inability to do so or difficulty in maintaining skills.

Conclusion

People with T2D have varied concerns and educational needs regarding injectables. GPs recognise the need to initiate injectables but lack practical skills and time to address patient concerns and provide education. Primary care nurses also report difficulties in maintaining these skills. Primary care HCPs initiating injectables require additional training to provide practical demonstrations, patient education and how to identify and address concerns. These skills should be concentrated in the hands of a small number of primary care providers to ensure they can maintain their skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Initiation of injectable therapy is often delayed by several years in type 2 diabetes, however the reasons for these delays are not understood. |

The study used multiple methods (focus groups, video-captured simulated consultations, and surveys) to identify barriers and facilitators to the initiation of injectable therapy. |

What was learned from the study? |

There are multiple patient barriers to initiation which include fear, lack of knowledge, and misconceptions. Good communication, clinician support and education can overcome barriers. |

In primary care, clinicians recognise the need to initiate injectable therapies but lack the required practical skills to do so and find it difficult to maintain competence. |

Additional training for primary care professionals initiating injectables is needed to support competency in this area. |

Introduction

Only around half of people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) achieve glycaemic targets [1,2,3]. A major component of suboptimal management is delayed treatment intensification termed “clinical inertia” [4]. Diabetes guidelines recommend stepwise treatment escalation [5, 6]. However, delayed intensification of glucose-lowering medication occurs at every stage of the treatment pathway; initiation of oral medication, addition of further oral medications, initiation of injectable therapies, and escalation of injectable therapies once initiated [7, 8]. The time to initiation of injectable therapies after maximal oral therapy is especially prolonged, with delays of 5–7 years reported [7, 9,10,11]. The mean threshold at which injectable therapies are initiated is also very high, with mean HbA1c values at initiation over 80 mmol/mol (9.5%) [12, 13]. Delayed intensification to injectable therapy likely increases risk for microvascular and macrovascular complications, reduces quality of life and increases mortality [14, 15].

Multiple factors have been associated with delayed initiation of injectable therapies and been categorised as clinician, patient, and health service-level factors [11, 16]. Clinician factors include a lack of awareness by general practitioners (GPs) of clinical inertia and lack of understanding of the need to achieve early glycaemic control [11, 17]. It has been hypothesised that both a lack of expert knowledge and consultation time with patients required to initiate insulin are major barriers in primary care [11]. Clinicians’ concerns about hypoglycaemia may also contribute [18]. Patient factors include fear of weight gain, hypoglycaemia, and concerns around the burden of injections and reduced quality of life [19, 20]. Improved understanding of the patient-, clinician-, and health service-level factors that influence clinical inertia is urgently needed to facilitate improved glycaemic control and health outcomes in T2D.

This study was designed to describe patients’ and healthcare professionals’ (HCPs) perceptions of the process of intensification with injectable therapies (insulin and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists [GLP1 RAs]), and the context within which those decisions are made. The goal was to enhance our understanding of clinical inertia and of what prevents appropriate initiation of injectable therapies in people with uncontrolled T2D despite maximum oral therapy.

Methods

The study research protocol has previously been reported in full [21]. In brief, we used a mixed methods design consisting of three phases.

-

Phase 1 We undertook separate focus groups with patients and HCPs (GPs and practice nurses) to explore their attitudes and experiences of the initiation of injectable therapies, and to examine their views on the facilitators and barriers to starting injectable therapy.

-

Phase 2 We observed consultations with GPs using fictional patients, played by actors, to simulate scenarios where injectable therapies could be initiated, to describe the context in which injectable therapy initiation takes place, including how well prompts and information from the computerised medical record (CMR) system are recognised in the consultation.

-

Phase 3 We used the results from the previous phases to devise a survey, which we sent to primary care HCPs across England, to describe consensus or discrepancy within and between clinicians and people with T2D about intensification to injectable therapies.

Setting

We recruited HCPs and patients with T2D from nine volunteer GP practices within the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Research and Surveillance Centre (RSC) network. The RCGP RSC is a large network of practices distributed across England which provides a broadly representative sample of the national population and high-quality data on diabetes care processes [22, 23].

In the UK, T2D is largely managed in primary care. Consultations are recorded into CMR systems that provide a mechanism to record diagnosis of T2D, prescription records, and pathology results, including HbA1c. Therefore, every time a person with T2D presents, their clinician can readily tell if they are achieving targets, and whether they are receiving appropriate therapy.

Since 2004 GPs have been financially remunerated for care quality in T2D through a pay-for-performance (P4P) system, the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) [24]. CMR-based interventions are known to improve glycaemic control [25] and the introduction of these P4P targets may have improved glycaemic control and reduced inequalities in T2D management [26, 27]. Despite these improvements the majority still have an HbA1c above target [26].

Participant Selection

Within each study practice we recruited adults with T2D; some naïve to injectable therapy, and others with current or prior experience (for Phase 1). We also recruited a mix of GPs and practice nurses (for Phase 1). We compared practice size, patient demographics, and diabetes QOF indicators of study practices with all practices in England to check representativeness of study practices.

Phase 1: Focus Groups with People with Type 2 Diabetes and Clinicians

We used focus groups as our primary method of data collection in this initial phase, but offered individual interviews to participants as an alternative (n = 1). Four patient and three HCPs focus groups were conducted separately to minimise response bias. A moderator introduced topics (Appendix 1) and ensured all participants were able to share views, and that all topics were covered. Each focus group lasted between 90 and 120 min. Transcripts were analysed using framework analysis (Appendix 1).

Phase 2: Video-Recorded Simulated Surgeries

We conducted simulated consultations (surgeries) with six of the seven GPs from Phase 1. Three fictional patient scenarios were generated (Appendix 2) by experts, using concepts and issues identified in Phase 1:

-

1.

Jane Smith: the appropriate therapeutic action was initiation of insulin.

-

2.

John Thompson: injectable therapy was not needed.

-

3.

Gary Jones: the appropriate therapeutic action was initiation of a GLP1 RA.

Patients’ roles were played by professional actors. Historic clinical data were entered into the CMR to produce prompts and access to guidelines that HCPs see to simulate routine surgeries as closely as possible.

Each consultation was video-recorded using the Activity Log File Aggregation (ALFA) toolkit [28]. The ALFA toolkit is a multi-channel video method that captures the minutiae of clinical consultation, such as verbal/non-verbal cues, and the impact of the computer, through simultaneous recording of (1) clinician’s upper body, (2) patient’s upper body, (3) wider angle capturing both patient and clinician, and (4) computer screen [28, 29].

Assessment of Consultation Quality

Consultation style has a major impact on patient–doctor relationships, substantially affecting the amount of information disclosed by patients [30]. We used The Global Consultation Rating Scale (GCRS) scoring template (Appendix 3), based on the Calgary–Cambridge consultation guide [31], to assess consultation quality [32]. The GCRS has been validated for assessment of simulated patient consultations and demonstrated to have good inter-rater reliability [32].

Assessment of the Interaction Between the GP and the Simulated Patient

A data capture form (Appendix 4) was developed for each simulated surgery to enable us to:

-

1.

Highlight key consultation elements that supported or negated need for action (therapy escalation to injectable treatment) either in patient’s history or simulated medical record

-

2.

Note whether each key consultation element was accessed in CMR or recognised during consultation

-

3.

Assess degree of patient or doctor-centeredness of consultation

-

4.

Describe outcome of consultation (captured through free text)

This analysis was carried out independently by two expert reviewers (JW and NM). The reviewers independently identified the six most important key elements, a priori, in the records or history from the simulated patient which should trigger action or prevent action, in this case intensification of therapy with injectable treatment. The videos were then independently reviewed by the experts using the data capture form to see if these triggers were recognised, discussed, and actioned. This peer approach mirrored similar methods used to assess multidisciplinary team meetings [33]. Inter-rater reliability of data capture was assessed using Cohen’s kappa.

Consultation outcomes were reported by the reviewers. These were coded as one or more of five potential outcomes:

-

1.

A prescription for insulin or a plan for the initiation of insulin

-

2.

A prescription for a GLP1 RA or a plan for the initiation of a GLP1 RA

-

3.

A prescription for the initiation or a plan for the initiation of a new oral medication

-

4.

A change in dose of a current oral medication

-

5.

No medication changes made

Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer (WH) by additional assessment of video data.

Follow-up Focus Groups: Including Assessing Consensus Statements

The GPs were subsequently invited to a follow-up focus group with a diabetologist, to ascertain their views on the scenarios and on factors influencing consultation outcome. In addition, they were presented with statements (Appendix 5) regarding care provision and initiation of injectable therapy in T2D and asked to rate their agreement/disagreement using a Likert scale. These statements were generated using the findings of Phase 1 focus groups and subsequently used to form the survey for Phase 3.

Phase 3: Survey

We developed a web-based survey for HCPs (Appendix 6) to quantify the extent to which themes identified in focus groups were representative of HCP views more broadly (by surveying practitioners across the RCGP RSC network). The survey incorporated a series of statements; participants indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each statement, using a Likert scale and described the rationale for their response.

Participants were also asked to indicate their role, gender, age, ethnicity, workplace location, and to categorise any diabetes-specific training that they had received.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

We received ethical approval from the Health Research Authority, London—Hampstead Research Ethics Committee (Ref 17/LO/1305). Each participant provided informed consent prior to involvement and all data were pseudonymised/anonymised as appropriate. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Results

HCPs from the nine practices participated in the focus groups, simulated surgeries, and helped recruit people with diabetes from their practices. Practices were broadly representative of practices in England and Wales in terms of size, prevalence of people with T2D, and patient sociodemographics. Study practices had a slightly better than average performance on diabetes QOF indicators (Appendix 7).

Phase 1: Focus Groups with People with Type 2 Diabetes and Clinicians

Seventeen people with T2D and 12 HCPs participated in focus groups (Tables S1, S2).

The people with T2D (n = 17) had a median age range of 65–74 years, and median duration of diabetes of 10–19 years. Half were male (53%) and they were an ethnically diverse sample (Table S1). Four participants were currently using insulin injectable therapy, one participant had been on insulin and returned to oral medication only; the remaining participants were naïve to injectable medications. Of the 12 clinicians, the median age range was 45–54, and three were male (25%). Seven clinicians were GPs and five were nurses, with nine reported having had some diabetes-specific training.

Reluctance to Start Injectable Therapy

Of the participants with T2D not on injectable therapy, all expressed a reluctance to start. Although one participant on injectable therapy recalled initial reluctance, all four participants currently on insulin described a positive experience with using it.

Emergent Themes

These are grouped into eight key themes with sample quotations (Table 1 and Appendix 8).

Barriers to the Initiation of Injectable Therapy

Theme 1: Lack of Understanding by People with Type 2 Diabetes

Lack of understanding about diabetes and injectable therapy were common among participants with T2D in this study. Given concordance with the clinicians’ views, it would suggest that low health literacy in relation to diabetes was widespread.

Theme 2: Fear

Some participants with T2D expressed fear in general terms, however others were more specific about reasons underpinning their fear. Participants with T2D and clinicians most commonly identified restriction of lifestyle as a reason for fear of injectables. Fear at the thought of self-administration was expressed by one person with T2D who was not on injectable therapy, as well as from clinicians. This contrasted with neutral reactions from those already using insulin. Areas of discordance between people with T2D and clinicians’ accounts of fear as a barrier to initiation of injectables were hypoglycaemic episodes, pain and fear of stigma. While these were raised by clinicians, these were not identified as significant sources of fear by people with T2D.

Themes 3: Comorbidities

Clinicians recognised comorbidities, such as impaired eyesight, overweight/obesity and age, as barriers for them to initiate administration of injectables for some patients.

Theme 4: Clinician Competence

The perceptions of participants with T2D varied widely in relation to individual clinician competence (clinician experience and knowledge used interchangeably). There was substantial variation in clinician confidence to initiate insulin therapy. While they felt able to discuss the potential for injectables with patients, some clinicians felt they did not have sufficient experience or knowledge to start this complex process. Clinicians acknowledged the importance of trust, particularly in the initiation of injectables. Where patients perceived their clinician to be competent, they reported having trust in them.

Theme 5: System Limitations

Lack of time was recognised as a major limiting factor for overall diabetes care and for the time-consuming initiation of injectable therapy by both clinicians and participants with T2D. High workloads were identified as another component of system constraints contributing to restricted time available for initiation of injectables. Cost was raised as an additional constraint by clinicians; the cost burden associated with patient equipment and choice of drug was also discussed. A lack of continuity of care was perceived to lead to a decline in the quality of diabetes care received by participants with T2D (but not by clinicians). Clinicians expressed frustration about the inconsistency of advice that patients received from GPs and diabetes clinics. Another inconsistency apparent within clinicians’ responses was the appropriate timing to discuss injectables with people with T2D; a number of clinicians felt that, at diabetes diagnosis, there was too much information for patients, while others believed that all information should be provided at diagnosis.

Facilitators to the Initiation of Injectable Therapy

Theme 6: Support for People with Type 2 Diabetes

People with T2D and clinicians recognised the importance of adequate support for people being initiated onto injectable therapy. Support from their leading clinician was reported as of paramount importance for people with T2D feeling willing/able to start injectable therapy. Adequate support helped with overcoming two of the most prominent barriers to initiation for people with T2D (i.e. misconceptions, fear). The need for practical advice, reassurance, and clearer rationale for needing injectables was noted by people with T2D and clinicians. Follow-up support was also identified as essential to ensure patients feel supported through their initiation of injectables.

The need to include family members in the initiation process was emphasised by clinicians. This was supported by narratives from people with T2D, who identified their families as crucial to their diabetes care and management of insulin regimens. Clinicians indicated that QOF targets and NICE guidelines support their decision-making for injectable therapy.

There was an overriding view that if people with T2D received the support they needed, they would overcome many of the barriers to initiation of injectable therapy.

Theme 7: Education

Both participants with T2D and clinicians identified improved diabetes-related education for patients as a major factor facilitating diabetes care and the initiation of injectable therapy. There was strong concordance across clinicians and participants with T2D that diabetes-related education for patients was key to the support that they need to overcome their barriers and accept initiation of injectables. Lack of time was recognised as a major obstacle to providing sufficient education that people with T2D require to fully understand the need for injectables.

Clinicians also expressed a strong interest in receiving more education/training for injectable therapy to provide the confidence and competence to initiate. Public health campaigns were mentioned by clinicians and people with T2D as a strategy to educate both the public and patients about the role of injectables in diabetes management.

Theme 8: Communication

Clear and more compassionate clinician communication was raised as a facilitator for initiation of injectables by people with T2D and links with the role of support and education from clinicians to encourage people to initiate injectable therapy. The participants with T2D stated the need for tailored, applied advice. Clinicians highlighted the need to improve their negotiation skills; when injectable therapy is broached during appointments, patients often engage in negotiation to avoid initiation.

Shared decision-making was a salient component of the diabetes care that the majority of the people with T2D felt that they received. Interestingly, participants with T2D who reported not being included in decisions about their own care also reported low levels of trust in their clinician.

Phase 2: Video-Recorded Simulated Surgeries

Six GPs participated in the simulated surgeries and follow-up focus groups (Table S3). The majority of participating GPs had over 30 years of healthcare experience. Each GP participated in a simulated surgery with all three patient actors. The mean consultation time was just over 13 min (range 9:25–16:49). Consultation quality was uniformly high across all the participating GPs (Supplementary Table S5).

Consultation Outcomes

The consultation outcomes for the three simulated patients are shown in Table 2. In case 1 (Jane Smith), none of the consulting GPs opted for the expert-recommended option of initiating insulin, although one clinician recommended further review after additional blood tests with potential for adding insulin. Three clinicians initiated a GLP1 RA despite the patient not being above the minimum BMI recommended for initiation in the UK. For case 2 (John Thompson), 5/6 consulting GPs opted for the expert-recommended option of making no changes. For case 3 (Gary Jones), 4/6 of GPs suggested addition of a GLP1 RA. One GP arranged for a further appointment to consider a GLP1 RA or other oral medication when the patient could provide additional information. Injectable devices or techniques were not discussed in any of the consultations.

Identification of Key Consultation Elements

GPs identified a mean of 3.8 of the six key elements needed to make a decision about escalation or maintenance of treatment across all simulated consultations (Table S5). Key elements relating to glycaemic control (e.g. HbA1c, osmotic symptoms) and patients’ expectations/wishes were well recognised by GPs, although other elements were less well explored (Table 3). Inter-rater reliability for clinician identification of key elements was excellent for majority of domains assessed (Table S6).

Phase 3: Survey

There were 87 HCP survey respondents, from 63 primary care workplaces distributed across the RCGP RSC network (Fig. S1): 41% (n = 36) were nurses and 56% were GPs (n = 49); the remainder were pharmacists (n = 2). All but one of the nurses was female, whereas the gender distribution was almost equal among GPs (Tables S7, S8). Participants described a wide range of prior diabetes-specific training.

An in-depth analysis of the survey results is provided in Appendix 9 and summarised in Table 4. The majority of survey respondents felt that initiating injectable therapies in people with T2D was usual practice in primary care without specialist input, stating that this would be done by a diabetes lead GP or nurse with diabetes expertise within the practice. Where respondents indicated that this was not done in their practices, this was either because a small number of people with diabetes meant they could not develop the required expertise or because this service was not commissioned locally. Where services were not commissioned in primary care, practitioners relied entirely on local specialist diabetes services for initiation of injectable therapies. Only half of the GPs and nurses surveyed reported the ability to initiate injectable therapy themselves, citing lack of training and lack of frequent exposure as reasons for their reticence.

HCPs reported the major factor causing the anxiety associated with starting injectable therapy is fear—of hypoglycaemia, injections, diabetic complications, and the implicit accusation of failure to manage lifestyle adequately. Nurses were more likely than GPs to respond to these fears by emphasising the importance of reassuring people with diabetes, and they valued the beneficial effects of peer support for people with T2D starting injections. HCPs broadly agreed that people with diabetes were reluctant to start injectable therapy. All HCPs were likely to consider social factors in relation to the likely efficacy/safety of treatment.

Regarding diabetes services organisation, nurses in primary care regarded QOF as incidental to the care that they provided. In contrast, while GPs did not universally endorse QOF treatment targets, they tended to believe that payments for performance had incentivised standardisation of care processes and raised the quality of diabetes care by their practices. Most HCPs felt that a lack of insulin prescribing courses was not a barrier to prescribing insulin in their localities but many, whilst keen, had not been on such a course. In contrast, a minority of participants felt that they had adequate access to training on GLP1 RA therapies. Whilst nurses generally did not report difficulty taking time out of clinical work to attend courses, GPs stated this was often difficult. The majority of nurses in primary care who participated in this study were not prescribers, but they were more likely than GPs to be the go-to people in their practices for initiation of injectable therapies.

Discussion

Focus groups demonstrated the barriers to initiation of injectable therapies in T2D include patient fear; a lack of knowledge and misconceptions about diabetes amongst those with T2D; concerns about potential lifestyle restrictions and social stigma; feelings of failure; concerns from clinicians about the interplay between insulin and comorbidities such as obesity or arthritis; and fear of adverse effects in both patients and clinicians. Facilitators to initiation include patient support, education, good communication, and clinician competence. In simulated consultations, GPs recognised the need for injectables and arranged initiation, although they preferred GLP1 RAs even where insulin was more appropriate. The reasons for this apparent preference are not clear but may include the weight loss benefit, lack of hypoglycaemia risk, or potential weekly administration of a GLP1 RA when compared with insulin. Survey results demonstrated HCPs feel injectable therapy initiation should be performed in primary care although many reported lack of skills to do so and difficulty in gaining and maintaining experience.

Interpreting our data collectively (see extended discussion—Appendix 10) we found that clinicians have reasonable scientific and theoretical knowledge of T2D and its treatments and an understanding of patient barriers to injectable therapy initiation. GPs also broadly have the ability to identify the need to escalate to injectable therapy in practice. However, they lack the technical know-how to initiate injectable treatment (skills that were more common in nurses) and did not always select the appropriate injectable therapy in simulated consultations. However, nurses within primary care also reported difficulties in achieving and maintaining the skills to initiate injectable therapy. This lack of technical know-how may lead to a mismatch between the perceived and actual role of primary care in initiation of injectable therapies.

In agreement with previous studies, we found that patients were generally reluctant to use injectable treatments. Many of the patient factors potentially contributing to delayed initiation that we identified have been previously recognised, including misconceptions, concerns regarding social stigma, association of insulin with personal failure [18, 20, 34, 35]. To initiate injectable therapies, patients reported needing skilled and compassionate healthcare providers who they trusted. These factors have also been previously recognised as demonstrated by a recent systematic review of qualitative studies [36]. They also felt the need for additional education about diabetes in general, to be given reasons for treatment, and a practical demonstration of the injection method. Practical demonstration of GLP1 RA injection has previously shown to influence patient medication preference [36, 37]. The unique perspective in our study, compared with previous similar analyses [36], was the video-recorded simulated surgeries. These have led us to identify a barrier which appears not to have been fully appreciated in previous studies, namely the potential mismatch between the perceived role of primary care in initiation of injectable therapies and the available technical skills to deliver this.

Implications for Clinical Practice

The barriers identified here are modifiable targets. There is a need to upskill practitioners with the technical skills to support patients with the initiation of injectable therapies. Given the reports of small numbers of patients within each practice going through this process and care providers’ difficulties in maintaining competence, this skill set should be concentrated in the hands of one or two care providers within each practice or group of practices. These practitioners require familiarity with different options for injectable therapies, to be able to select appropriate treatment options, and an ability to demonstrate their use to patients. In addition, they should be able to provide the education patients require to understand treatment rationale and be able to identify and address patients’ personal concerns or fears. It should also be recognised that this process is complex and requires adequate time and follow-up. A well-structured national training programme is required to address these current issues and should be carefully scrutinised for effectiveness.

Strengths and Limitations

We have previously reported key strengths (representativeness of the sample, the high fidelity of the simulated surgeries, and benefits of both a micro and macro perspective) and limitations (limiting to English language participants, potential for interference of video in the observed consultations) of the study design [21].

Some additional limitations are noteworthy: firstly, data collection was designed to examine barriers to initiation of insulin and GLP1 RAs, yet we were unable to recruit any people with diabetes with GLP1 RA experience; therefore, the data presented focused on insulin. The HCPs had some limited experience of GLP1 RAs. Secondly, it is near impossible to prepare the patient actors to correctly answer all possible questions they may get asked during the consultation, and therefore some answers given may have been misleading in the consultation. We identified a few minor examples of this but our expert reviewers felt that this did not have a major effect on any of the consultations. Finally, for the video-studies we were required to inform the GPs about the overall purpose of the study. They were therefore aware that the research was exploring barriers and facilitators to the initiation of injectable therapies in T2D. This knowledge may have biased decision-making in the simulated consultations although we still found that GPs did not initiate insulin in our first scenario.

Conclusions

Primary care in the UK provides an appropriate setting for the initiation of injectable therapies and care providers widely report they feel initiation of injectables should be performed in primary care. However, whilst practitioners readily recognise patients requiring treatment escalation, they lack the technical know-how to select and initiate the correct therapy. Patients are also often not ready to initiate injectable therapies as a result of a lack of knowledge, misconceptions and fear. Improving the knowledge, skills and confidence of a selected group of practitioners in primary care would facilitate provision of knowledge and practical skills required to successfully initiate injectable therapies for people with T2D.

References

Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saaddine JB, Cowie CC, Imperatore G, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in US diabetes care, 1999–2010. New Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1613–24.

Khunti K, Ceriello A, Cos X, De Block C. Achievement of guideline targets for blood pressure, lipid, and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;137:137–48.

Stone MA, Khunti K, Charpentier G, et al. Quality of care of people with type 2 diabetes in eight European Countries: findings from the guideline adherence to enhance care (GUIDANCE) study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2628–38.

Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia; time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105–6.

Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 201841(12):2669–701.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. NICE guideline [NG28]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28. Accessed 02 Aug 2022.

Khunti K, Wolden ML, Thorsted BL, Andersen M, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013:DC_130331.

Khunti K, Nikolajsen A, Thorsted BL, Andersen M, Davies MJ, Paul SK. Clinical inertia with regard to intensifying therapy in people with type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(4):401–9.

Rubino A, McQuay LJ, Gough SC, Kvasz M, Tennis P. Delayed initiation of subcutaneous insulin therapy after failure of oral glucose-lowering agents in patients with type 2 diabetes: a population-based analysis in the UK. Diabet Med. 2007;24(12):1412–8.

Nichols GA, Koo YH, Shah SN. Delay of insulin addition to oral combination therapy despite inadequate glycemic control: delay of insulin therapy. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(4):453–8.

Khunti K, Millar-Jones D. Clinical inertia to insulin initiation and intensification in the UK: a focused literature review. Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(1):3–12.

Harris SB, Kapor J, Lank CN, Willan AR, Houston T. Clinical inertia in patients with T2DM requiring insulin in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(12):e418–24.

Hinton W, McGovern A, Whyte M, et al. What are the HbA1c thresholds for initiating insulin therapy in people with type 2 diabetes in UK primary care? Diabetologia. 2016;59:S416–7.

Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133–8.

Goodall G, Sarpong EM, Hayes C, Valentine WJ. The consequences of delaying insulin initiation in UK type 2 diabetes patients failing oral hyperglycaemic agents: a modelling study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2009;9(1):19.

Bralic Lang V, Bergman Markovic B, Kranjcevic K. Family physician clinical inertia in glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:403–11.

Zafar A, Stone MA, Davies MJ, Khunti K. Acknowledging and allocating responsibility for clinical inertia in the management of type 2 diabetes in primary care: a qualitative study. Diabet Med. 2015;32(3):407–13.

Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm-Draeger P-M. Insulin adherence behaviours and barriers in the multinational Global Attitudes of Patients and Physicians in Insulin Therapy study. Diabet Med. 2012;29(5):682–9.

Kunt T, Snoek FJ. Barriers to insulin initiation and intensification and how to overcome them. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(s164):6–10.

Polonsky WH, Jackson RA. What’s so tough about taking insulin? Addressing the problem of psychological insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2004;22(3):147–50.

de Lusignan S, Hinton W, Konstantara E, et al. Intensification to injectable therapy in type 2 diabetes: mixed methods study (protocol). BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):284.

Correa A, Hinton W, McGovern A, et al. Cohort profile: Royal College of General Practitioners Research (RCGP) and Surveillance Centre (RSC) sentinel network. BMJ Open. 20166(4):e011092.

McGovern A, Hinton W, Correa A, Munro N, Whyte M, de Lusignan S. Real-world evidence studies into treatment adherence, thresholds for intervention and disparities in treatment in people with type 2 diabetes in the UK. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e012801.

NHS Digital. Quality and outcomes framework 2018. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/quality-and-outcomes-framework-achievement-prevalence-and-exceptions-data/2018-19-pas. Accessed 2 Aug 2022.

Alharbi NS, Alsubki N, Jones S, Khunti K, Munro N, de Lusignan S. Impact of information technology-based interventions for type 2 diabetes mellitus on glycemic control: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(11): e310.

Oluwatowoju I, Abu E, Wild SH, Byrne CD. Improvements in glycaemic control and cholesterol concentrations associated with the Quality and Outcomes Framework: a regional 2-year audit of diabetes care in the UK. Diabet Med. 2010;27(3):354–9.

Alshamsan R, Millett C, Majeed A, Khunti K. Has pay for performance improved the management of diabetes in the United Kingdom? Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(2):73–8.

de Lusignan S, Kumarapeli P, Chan T, et al. The ALFA (Activity Log Files Aggregation) toolkit: a method for precise observation of the consultation. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10(4): e27.

Kumarapeli P, de Lusignan S. Using the computer in the clinical consultation; setting the stage, reviewing, recording, and taking actions: multi-channel video study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(e1):e67-75.

Silverman J, Kinnersley P. Doctors’ non-verbal behaviour in consultations: look at the patient before you look at the computer. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(571):76–8.

Kurtz SM, Silverman JD. The Calgary-Cambridge referenced observation guides: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Med Educ. 1996;30(2):83–9.

Burt J, Abel G, Elmore N, et al. Assessing communication quality of consultations in primary care: initial reliability of the Global Consultation Rating Scale, based on the Calgary-Cambridge guide to the medical interview. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e004339.

Harris J, Green JS, Sevdalis N, Taylor C. Using peer observers to assess the quality of cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: a qualitative proof of concept study. J Multidiscipl Healthc. 2014;7:355–63.

Jenkins N, Hallowell N, Farmer AJ, Holman RR, Lawton J. Participants’ experiences of intensifying insulin therapy during the Treating to Target in Type 2 Diabetes (4-T) trial: qualitative interview study. Diabet Med. 2011;28(5):543–8.

Hunt LM, Valenzuela MA, Pugh JA. NIDDM patients' fears and hopes about insulin therapy: the basis of patient reluctance. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(3):292–8.

Byrne J, Willis A, Dunkley A, et al. Individual, healthcare professional and system-level barriers and facilitators to initiation and adherence to injectable therapies for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Diabet Med. 2022;39(1): e14678.

Boye K, Ross M, Mody R, Konig M, Gelhorn H. Patients’ preferences for once-daily oral versus once-weekly injectable diabetes medications: the REVISE study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(2):508–19.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank patients, healthcare providers, and practices that participated in this study.

Funding

This work and journal’s Rapid Service Fee is funded and sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

We would like to thank Jeremy van Vlymen of the University of Surrey, for statistical support.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Simon de Lusignan and William Hinton designed the mixed methods study and study components with critical review from Andrew McGovern, Emmanouela Konstantara, Julie Mount, Filipa Ferreira, Martin Whyte, Neil Munro, and Michael Feher. Emmanouela Konstantara performed the data collection with support from William Hinton, Manasa Tripathy, Filipa Ferreira, Martin Whyte, Neil Munro, Michael Feher, and Simon de Lusignan. Manasa Tripathy formatted the video-recordings of simulated surgeries as per the ALFA toolkit set-up. Benjamin. Field, William Hinton, Martin Whyte, Neil Munro, John Williams, Emily Williams, Afrodita Marcu, Andrew McGovern, and Emmanouela Konstantara performed the analysis and synthesis of the data. Simon de Lusignan, Andrew McGovern and Benjamin. Field wrote the manuscript with critical review and contributions from William Hinton, Martin Whyte, Neil Munro, Emily Williams, Afrodita Marcu, John Williams, Filipa Ferreira, Julie Mount, Emmanouela Konstantara, Manasa Tripathy, and Michael Feher.

Disclosures

Simon de Lusignan holds grants from Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, AstraZeneca, and Novo Nordisk Ltd. through the University of Surrey for investigator lead research in diabetes; William Hinton has had part of his academic salary funded through these awards (Eli Lilly and Company, Novo Nordisk Ltd., and AstraZeneca UK Ltd). Neil Munro has received financial support for research, speaker meetings, and consultancy from MSD, Merck, BMS, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk Ltd., and Sanofi-Aventis. Martin Whyte has received financial support for speaker meetings from AstraZeneca and MSD, and support for research from Eli Lilly and Company and Sanofi-Aventis. Michael Feher has received financial support for research and speaker meetings from Novo Nordisk Ltd., and Sanofi-Aventis. Julie Mount is employed by Eli Lilly and Company. Andrew McGovern declares research funding from Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Company, and AstraZeneca. Emily Williams, Afrodita Marcu, John Williams, Filipa Ferreira, Manasa Tripathy, Emmanouela Konstantara, Benjamin. Field declare that they have no competing interests.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

As described in the methods this study used a sequential design where patient responses in study Phase 1 were utilised to inform the subsequent study phases. We received ethical approval from the Health Research Authority, London—Hampstead Research Ethics Committee (Ref 17/LO/1305). Each participant provided informed consent prior to involvement and all data were pseudonymised/anonymised as appropriate. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Data Availability

To protect patient confidentiality data from this study cannot be made publicly available. Limited anonymised data can be made available to bona fide researchers on a case-by-case basis. Please contact the corresponding author to make a request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Lusignan, S., McGovern, A., Hinton, W. et al. Barriers and Facilitators to the Initiation of Injectable Therapies for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Mixed Methods Study. Diabetes Ther 13, 1789–1809 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-022-01306-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-022-01306-z