Abstract

Background

The number of older adults with insulin-treated diabetes mellitus (DM) is steadily increasing worldwide. Errors in the insulin injection technique can lead to skin lipohypertrophy (LH), which is the accumulation of fat cells and fibrin in the subcutaneous tissue. While lipohypertrophic lesions/nodules (LHs) due to incorrect insulin injection techniques are very common, they are often flat and hardly visible and thus require thorough deep palpation examination and ultrasonography (US) for detection. Detection is crucial because such lesions may eventually result in poor diabetes control due to their association with unpredictable insulin release patterns. Skin undergoes fundamental structural changes with aging, possibly increasing the risk for LH. We have therefore investigated the effect of age on the prevalence of LHs and on factors potentially associated with such lesions.

Methods

A total of 1227 insulin-treated outpatients with type 2 DM (T2DM) referred to our diabetes centers were consecutively enrolled in the study. These patients underwent a thorough clinical and US evaluation of the skin at injection sites, as previously described, with up to 95% concordance betweenthe clinical and US screening techniques. Of these 1227 patients, 718 (59%) had LH (LH+) and 509 (41%) were LH-free (LH−). These patients were then assigned to two age class groups (≤ 65 years and > 65 years), and several clinical features, diabetes complication rates, and injection habits were investigated.

Results

Comparison of the two age subgroups revealed that 396 (48%) and 322 (79%) patients in the younger and older groups, respectively, had LHs (p < 0.001). Compared to the younger subgroup, the older subgroup displayed a higher LH rate in the abdomen (52.9 vs. 38.3%; p < 0.01) and a lower rate in the arms (25.4 vs. 35.8%; p < 0.05), thighs (26.7 vs. 33.4%; p < 0.05), and buttocks (4.9 vs. 26.2%; p < 0.01). In older subjects, the most relevant parameters were: habit of injecting insulin into LH nodules (56 vs. 47% [younger subjects]; p < 0.01), rate of post-injection leakage of insulin from injection site (drop-leaking rate; 47 vs. 39% [younger subjects]; p < 0.05), and rate of painful injections (5 vs. 16% [younger subjects]; p < 0.001). Multivariate analysis showed a stronger association between LH and poor habits, as well as between several clinical parameters, among which the most relevant were hypoglycemic events and glycemic variability.

Discussion

The higher rate of post-injection drop-leaking and pain-free injections might find an explanation in skin changes typically observed in older adults, including lower thickness, vascularity and elasticity, and a more prominent fibrous texture, all of which negatively affect tissue distensibility. Consequently, in addition to the well-known association between aging skin impaired drug absorption rate, aging skin displays a progressively decreasing ability to accommodate large volumes of insulin-containing fluid.

Conclusions

The strong association between LH rate and hypoglycemic events plus glycemic variability suggests the need (1) to take specific actions to prevent and control the high risk of acute cardiovascular events expected to occur in older subjects in the case of hypoglycemic events, and (2) to identify suitable strategies to fulfill the difficult task of performing effective educational programs specifically targeted to the elderly.

Trial Registration

Trial registration number 172–11:12.2019, Scientific and Ethical Committee of Campania University “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Naples, Italy).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Insulin injection technique errors can cause a high rate of skin lipohypertrophic lesions (LHs), but these lesions are often flat and barely visible, thus requiring thorough deep palpation examination and ultrasonography (US) for identification. |

Detection of LHs is crucial to prevent poor diabetes control due to unpredictable insulin-release patterns. |

The skin undergoes fundamental structural changes with aging, potentially increasing the risk for LHs. |

In this study, 718 outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with LHs were assigned to one of two age class subgroups (≤ 65 years and > 65 years) in order to evaluate whether age influences LH prevalence and various factors associated with LHs. |

The older group was found to show a stronger association between LHs and poor habits, as well as with several clinical parameters, among which the most relevant were hypoglycemic events and glycemic variability. |

The results suggest the need (1) to take specific actions to prevent and control the high risk of acute cardiovascular events expected to occur in older subjects in the case of hypoglycemic events, and (2) to identify and establish better-targeted, effective educational programs specifically in patients in the older age category. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13117835.

Introduction

Increases in life expectancy have resulted in the ageing population representing an increasingly larger segment of the world’s population, with one consequence being that the number of people aged > 65 years having diabetes mellitus (DM) is also rising worldwide [1]. The prevalence of both DM and insulin utilization also increases with age due to progressive beta-cell failure and chronic DM complications contraindicating alternative hypoglycemic agents [2].

Insulin activity is known to be optimized in children and adults through the use of correct injection modalities [3], but in elderly patients a number of factors other than injection technique affect insulin activity, including pruritus, carcinomas, melanomas, frequently occurring skin morphological/functional changes, and skin disorders, have to be taken into account as a consequence of increasing age [4]. The skin undergoes fundamental structural changes with aging, such as increased fragility, decreased healing potential, and increased susceptibility to toxic injuries, which may precipitate various disorders/diseases and result in aesthetically undesirable effects (e.g., wrinkling and uneven pigmentation) [4].

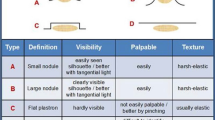

Errors in insulin injection techniques cause lipohypertrophic nodules (LHs) to develop in the skin. Such lesions consist of fat cells and fibrin that accumulate in the subcutaneous tissue with or without tissue tinting [5, 6]. The rate of LHs is quite high among insulin-treated persons with DM and has been reported to exceed 50% of this patient population [7]. Due to their firm–elastic texture, LHs modify skin consistency and elasticity. Nevertheless, they are sometimes flat and hardly visible, thus requiring thorough deep palpation examination and ultrasonography (US) for detection.

In this context, we have investigated the possibility of risk factor-matched age-dependent differences in prevalence of LHs as the primary endpoint of our study, and the localization of LHs and associated factors as secondary endpoints.

Methods

This study is a sub-analysis of data collected in a multicenter survey [8] conducted by eight Italian outpatient diabetes units (DCs) that share electronic record systems, diagnostic–therapeutic procedures, and operating standards, and participate in the continuous care improvement program of the National Clinical Diabetology Association (AMD) (https://www.aemmedi.it). The specialists participating in the study had undergone full training on all procedures described in the study.

Eligibility criteria were: age > 18 years; duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) of at least 5 years; lifestyle-only treatment, with the exception of insulin pen treatment twice daily or more for at least 1 year. Those unable to either complete the questionnaire or fully understand its content were not considered eligible for the study and excluded after initial enrollment.

The questionnaire, derived from the web-based clinical record form, examined several aspects of T2DM, as described elsewhere [9], but focused on aspects closely related to injection technique, including type of needle, failure to rotate injection sites, needle reuse, habit of injecting ice-cold insulin, post-injection leakage of insulin from the injection site (drop-leaking), and local discomfort/pain/redness/itching or other changes at the injection site. Other relevant aspects were age, gender, severe hypoglycemic episodes (HEs) over the past 12 months, and experience of symptomatic HEs in the past 4 weeks. Relevant clinical characteristics of the subjects enrolled in the study, T2DM-related factors, including complications and treatments, and parameters associated with the insulin injection technique were also recorded (Table 1).

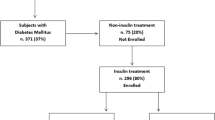

Of the 3234 insulin-treated outpatients consecutively referred to our DCs, 1227 with T2DM were enrolled as meeting the recruitment criteria. All 1227 subjects underwent a clinical and US evaluation of the skin in search of LHs at insulin injection sites, as previously described [10, 11]. The evaluations identified 718 (59%) patients with skin lipohypertrophy (LH+) and 509 (41%) without LH (LH-free [ (LH−]).

The diagnosis of T2DM was based on criteria defined by the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2019 [12]. The International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM, diagnosis code V82.9) was used to define DM-related or -unrelated comorbidities and complications [13].

The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-Epi) formula was used to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Of the 442 subjects with nephropathy, 24 had end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the dialysis phase and were followed-up according to an integrated management protocol in ten dialysis centers associated with the involved DCs.

HEs were defined according to ADA guidelines 2019 [12] as frequent unexplained HEs when occurring at least once a week in the absence of any identified precipitating event (i.e., changed insulin dosage, diet composition, or physical activity) and further distinguished into severe (SH) or non-severe (NSH) based on attained blood glucose levels (i.e., < 50 mg/dl or 51–70 mg/dl, respectively) [9].

Glycemic variability (GV) was evaluated by considering the mean [5] of glycemic fluctuations occurring over the observation period, when patients monitored capillary blood glucose both immediately before and 2 h after breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and at midnight, as reported elsewhere [14]. In the absence of any user-friendly, unanimously accepted clinical method, we investigated GV through a validated questionnaire [15] and defined it as high in the case of blood glucose levels swinging consistently, inexplicably, and unpredictably from < 60 to > 250 mg/dl at least once a week over the 3 months immediately preceding enrollment and for least for 3 weeks within the first and second trimester of the study, as previously described [5, 8, 15].

We identified LHs at all injection sites according to a validated clinical method described elsewhere [8, 10, 11]. Briefly, a well-trained staff with > 3 years of experience carefully followed a clearly defined patient inspection procedure with the patient in the supine, sitting, and standing position, both from the front and from the side. This was followed by a thorough gel-assisted, increasingly deep, repeated palpation procedure, in combination with a pinching maneuver in the case of suspected hardly visible/palpable LHs within a pasty and less elastic skin area. An in-depth description of our manual procedure to identify LH size is given in our previous publications together with detailed images [8, 10]. The minimum size is that of a lentil in the case of nodular LHs and 2 cm in the case of flat LHs. A further assessment, especially for the smallest lesions, required high-frequency B-mode US scanning at all injection sites in all patients enrolled in the present study. US scanning also allowed us to concentrate only on LHs by excluding any other lesions characterized by a similar density and texture, such as cysts, lipomas, or amyloid nodules. In questionable cases, i.e., detection of extremely small LHs, the site was classified as LH−.

Data were analyzed anonymously. This study was conducted in conformance with good clinical practice standards and was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki 1975, as revised in 2008. It was approved by Vanvitelli University, Naples, Italy (Trial registration number 172–11:12.2019) and by all of the ethics committees of the centers participating in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment.

Statistical Analysis

Patients’ characteristics were reported as the mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables or in terms of number/percentages for categorical variables. Parameters associated with injection techniques were subjected to repeated measures analysis of variance integrated by two-tailed paired Student’s t test with 95% confidence intervals for parametric variables and Mann–Whitney’s U test for non-parametric variables. The Chi-square (χ2) test with Yates correction or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. A p < 0.05 was chosen as the least acceptable statistical significance level. All evaluations were performed using SAS statistical software release 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The concordance between the results from clinical and US scanning examination in terms of LH detection was as high as 95%. Using the pre-determined age cut-off to separate the subjects into two age groups, 817 (67%) and 410 (33%) subjects were grouped into the age groups of ≤ 65 and > 65 years, respectively.

As shown in Table 1, the subjects in the older group differed from their younger counterparts in terms of gender (23% of subjects in older group were male vs. 40% in younger group; p < 0.05), body mass index (lower in the older group: 27 ± 6 vs. 31 ± 5 kg/m2; p < 0.005), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (higher in the older group: 8.9 ± 1.4 vs. 8.1 ± 1.2%; p < 0.05), disease duration (longer in the older group: 12 ± 9 vs. 9 ± 7 years; p < 0.05), duration of treatment with insulin (longer in the older group: 12 ± 5 vs. 8 ± 4 years; p < 0.01), daily insulin requirement (lower in the older group: 43 ± 11 vs. 49 ± 15 IU/day; p < 0.01), prevalence of HEs (higher in the older group: 65 vs. 51; p < 0.01), glycemic variability (greather in the older group: 347 ± 69 vs. 281 ± 62 mg/dl; p < 0.001), and frequency of complications (higher in the older group). However, most of the parameters of the injection procedure were superimposable in the two age groups, including needle reuse (65 vs. 61%; p = not significant [n.s.]), failure to rotate injection sites (46 vs. 49%; p = n.s.), injection of ice-cold insulin (49 vs. 51%; p = n.s.), required (10–20 s) post-injection needle removal lag time (6 vs. 9%; p = n.s.), although the older patients observed post-injection drop-leaking more frequently (47 vs. 39%; p < 0.05), had a significantly greater habit to inject insulin into LHs (47 vs. 39%; p < 0.01) and had a significantly lower rate of painful injections (5 vs. 16%; p < 0.001).

As roughly seen from Fig. 1, the most frequent location of LHs in the subjects in both age groups was the abdomen; other locations were relatively evenly distributed in the subjects in both age classes. However, some differences between age classes were apparent: compared to the younger subgroup, the older subgroup had a higher rate of LHs in the abdomen (52.9 vs. 38.3%; p < 0.01) and a lower rate in the arms (25.4 vs. 35.8%; p < 0.05), (26.7 vs. 33.4%; p < 0.05), and buttocks (4.9 vs. 26.2%; p < 0.01).

Graphic representation of the distribution of skin lipohypertrophic lesions (LHs) on the body surface of younger (≤ 65 years) and older (> 65 years) subjects. The colored circles represent the body areas in which LHs are present, with a higher color intensity and a larger size indicating a higher frequency of LHs

Data from both subgroups were subjected to multivariate analysis to look for any possible associations among the investigated factors and LHs. Table 2 shows the only parameters found to be significantly associated with the presence of LHs. The same associations were significant in both groups, but hazard risk values were higher in the older subgroup.

Discussion

Our survey clearly shows that LHs due to poor/inadequate insulin injection technique were significantly more frequent in the older subjects than in the younger ones (79 vs. 48%; p < 0.0001). A large body of evidence suggests that LHs are invariably associated with needle reuse and failure to rotate injection sites and are more frequent in subjects with longer diabetes duration, especially females. There is also considerable agreement in the literature regarding a strong association between LH and high SH or NSH rates, large GV, and worse HbA1c [5, 7, 8, 14,15,16], but not with high insulin doses. Although our results support the findings from the majority of these published reports, we found that the injection of cold insulin occurred in about 50% of patients independently of age and that it was significantly associated with rate of LHs, as if the cryo-traumas per se functioned as an add-on to repeated mechanical trauma in terms of LH-related factors.

The older subjects in our study suffered cardiovascular and renal complications more frequently than the younger ones. This aspect deserves special attention as both frequent HEs and a large GV act as independent cardiovascular risk factors per se by causing well-established and considerable macro- and micro-vascular changes [17,18,19,20]. We report here for the first time a close relationship between injection-related LHs and ESRD/dialysis in aged subjects. Thus, given the association with a more prominent risk for HEs, in frail subjects a higher LH rate may represent an add-on factor triggering acute complications [20], which can be prevented by correcting injection technique errors and by injecting insulin far from LHs.

Despite almost superimposable injection habits in the two age groups, our data also suggest an equally strong association of LHs with injection technique errors, although we observed a higher prevalence of post-injection drop-leaking (47 vs. 39%; p < 0.05) and a lower rate of painful injections (5 vs. 16%; p < 0.01) in older subjects, possibly related to skin changes typically observed in older adults. The aging skin becomes thinner, loses vascularity and elasticity, and becomes more fibrous in texture [4, 21, 22], all factors contributing to reduced tissue distensibility. As a consequence of these changes with age, the skin becomes increasingly less able to accommodate an ever-increasing volume of insulin-containing fluid. The lower rate of painful injections may also reflect skin changes with aging, which are typically characterized by progressively higher denervation processes [23].

In terms of the distribution of LHs, we found the abdomen to be the preferred injection site, followed by the arms, thighs and buttocks in decreasing order of preference [5, 24]. Despite being potentially random, this distribution across the body may well depend on the manual skills of the patient, the style of dress, or functional hand/arm joint deficits, all possibly making the abdomen more convenient for injections, especially when outdoors. These are only hypotheses, as the observed phenomena may simply be chance or depend on other age-related factors, such as physical stiffness hindering injections outside the abdominal area, inveterate behavior, or laziness. In our opinion, abdominal sites do not contribute to the occurrence of LHs in older patients more than other sites, despite LHs appearing less frequently at these other sites.

It is also possible that typical changes in age-related subcutaneous fat distribution may also cause the different LH rate observed in the older subjects [4, 21].

In summary, the higher frequency of cutaneous LHs due to incorrect insulin injection technique in our older subgroup, described here for the first time, seems to be mostly driven by age-related behavioral aspects and skin alterations. However, the strong association between LH rate and HE risk suggests the need (1) to take specific actions to prevent and control the high risk of hypoglycemia and of consequent acute cardiovascular events in older patients and (2) to identify suitable strategies to fulfill the difficult task of performing effective educational programs specifically targeted to the elderly.

As a first and easy to implement solution, we suggest the use of pens to deliver concentrated insulins, like the U-200 pen for the fast-acting analog and U-300 pen for the long-acting one. The use of pens may be of particular help to older adults by reducing the injected volume.

Regarding a practical approach to educating patients on correct injection techniques, there have been a few good studies, although these are characterized by a small number of subjects and a short-duration follow-up [25, 26]. We performed a preliminary analysis of the cost-saving effects of structured education on correct injection techniques in terms of reduced severe HE-related hospital emergencies [27]. We are fully aware that older people cannot train effectively to act appropriately after inadvertently have bad habits for years. However, we also feel a large responsibility to fight therapeutic inertia given the evidence for severe—and even potentially life-threatening—HEs due to an avoidable high rate of LHs. We feel that a new structured education approach that is specifically designed for the elderly should be implemented on an experimental basis, possibly based on models showing effectiveness for other purposes, like the so-called “group care” model [28, 29]. It is notable that even showing patients their lesions during US scanning procedures has proven to be quite convincing and educationally compelling per se [8].

There is one final consideration that deserves attention: the real reasons behind LH occurrence are still unknown. Independent of underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, as is seen above, LHs are a consequence of inappropriate injection techniques. Getting to know how to inject insulin correctly and to do so in real life is not easy. It requires adequate training initially, followed by refresher courses at regular intervals after repeated performance checks and careful injection site examination in search of possibly occurring LHs. A common complaint is the large discrepancy observed among studies held in care settings of different clinical approaches, countries, and identification methods.

Consequently, in past publications we have also criticized research groups unable to adopt a strict, repeatable, and safe LH identification method [8, 10, 11]. Even more, we have pronounced the high prevalence of LH lesions as evidence that clinicians are not sufficiently interested in this problem and have allowed patients to carry out their insulin treatment in a non-systematic and somewhat careless manner [30, 31]. Such criticism sounds like a defeat for clinicians. Otherwise, we would not read so many papers on this topic that report huge differences in LH rates. Things might get much better just by following a systematic, repeated search for LHs in clinical practice and reinforcing correct messages by appropriate education refresher courses. As seen, older adults, i.e., the frailest subjects, have a higher rate of LH occurrence than their younger counterparts. Therefore, they need to be checked for LHs more frequently and be provided with thorough education by healthcare personnel and possibly also by caregivers to avoid major acute cardiovascular events and long-term brain damage, eventually causing mild cognitive impairment leading up to dementia [32]. It is now time to regularly monitor the situation to avoid continuing with merely theoretical investigations and eventually provide our frail patients with the best possible care.

Limitations

Our interpretation of different LH rates and insulin injection habits between age classes relies only on hypotheses, albeit plausible hypotheses that are based on indirect evidence.

Nevertheless, our study is the first comparison of subjects of different age classes, and the data obtained unequivocally points to several critical issues related to incorrect insulin injection techniques. This requires clinicians to pay more attention to this aspect of diabetes care, especially when dealing with the elderly who usually have to overcome inveterate practices and have greater learning difficulties than young adults. The link between LH pathophysiology and age-related factors is still missing sound evidence, and we therefore suggest exploring this aspect in the future.

References

World Health Organization, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Global health and aging. https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

Selvin E, Parrinello CM. Age-related differences in glycaemic control in diabetes. Diabetologia. 2013;56(12):2549–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-3078-7.

Frid AH, Kreugel G, Grassi G, et al. New insulin delivery recommendations. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(9):1231–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.010.

Farage MA, Miller KW, Elsner P, Maibach HI. Characteristics of aging skin. Adv Wound Care. 2013;2(1):5–10.

Blanco M, Hernández MT, Strauss KW, Amaya M. Prevalence and risk factors of lipohypertrophy in insulin-injecting patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39:445–53.

Bertuzzi F, Meneghini E, Bruschi E, Luzi L, Nichelatti M, Epis O. Ultrasound characterization of insulin induced lipohypertrophy in type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol Investig. 2017;40(10):1107–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-017-0675-1.

Deng N, Zhang X, Zhao F, Wang Y, He H. Prevalence of lipohypertrophy in insulin-treated diabetes patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2017;9:536–43.

Gentile S, Guarino G, Della Corte T, et al. Insulin induced skin lipohypertophy in type 2 diabetes: a multicenter regional survey in southern Italy. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11(9):2001–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00876-0.

Giorda CB, Ozzello A, Gentile S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for severe and symptomatic hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Results of the HYPOS-1 study. Acta Diabetol. 2015;52(5):845–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-015-0713-4.

Gentile S, Guarino G, Giancaterini A, Guida P, Strollo F, AMD–OSDI Italian Injection Technique Study Group. A suitable palpation technique allows to identify shkin lipohypertrophic lesions in insulin-treated peope with diabetes. Springerplus. 2016;5:563. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-1978-y.

Gentile S, Strollo F, Guarino G, et al. Factors hindering correct identification of unapparent lipohypertrophy. J Diabetes Metab Disord Control. 2016;3(2):42–7. https://doi.org/10.15406/jdmdc.2016.03.00065.

American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes–2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S13–S28. https://doi.org/10.2337//dc10-S002.

National Center for Health Statistics. International classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm. Accessed Jan 2018.

Gentile S, Strollo F, Satta E, et al. Insulin-related lipohypertrophy in hemodialyzed diabetic people: a multicenter observational study and a methodological approach. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(4):1423–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-019-0650-2.

Frid AH, Hirsch LJ, Menchior AR, Morel DR, Strauss KW. Worldwide injection technique questionnaire study: injecting complications and the role of the professional. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(9):1224–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.012.Review.

Ji L, Sun Z, Li Q, et al. Lipohypertrophy in China: prevalence, risk factors, insulin consumption, and clinical impact. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2017;19(1):61–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2016.0334.

Snell-Bergeon JK, Wadwa RP. Hypoglycemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(Suppl 1):S51–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2012.0031.

Zhou JJ, Schwenke DC, Bahn G, Reaven P, VADT Investigators. Glycemic variation and cardiovascular risk in the veterans affairs diabetes trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(10):2187–94. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-0548).

Liang S, Yin H, Wei C, Xie L, He H, Liu X. Glucose variability for cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2017;14(16):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40200-017-0323-5.

Hanefeld M, Frier BM, Pistrosch F. Hypoglycemia and cardiovascular risk: is there a major link? Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 2):S205–9. https://doi.org/10.2337/dcS15-3014.

Fore J. A review of skin and the effects of aging on skin structure and function. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2006;52(9):24–35 (Quiz 36–37).

Waller JM, Maibach HI. Age and skin structure and function, a quantitative approach. II: blood flow, pH, thickness, and ultrasound echogenicity. Skin Res Technol. 2005;11:221–35.

Alsunousi S, Marrif HI. Diabetic neuropathy and the sensory apparatus “meissner corpuscle and merkel cells.” Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:79. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2014.00079.

Hirsch LJ, Strauss KW. The injection technique factor: what you don’t know or teach can make a difference. Clin Diabetes. 2019;37(3):227–33. https://doi.org/10.2337/cd18-0076.

Smith M, Clapham L, Strauss K. UK lipohypertrophy interventional study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;126:248–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.01.020.

Campinos C, Le Floch JP, Petit C, et al. An effective intervention for diabetic lipohypertrophy: results of a randomized, controlled, prospective multicenter study in France. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2017;19(11):623–32. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2017.0165.

Gentile S, Strollo F, on behalf of the Nefrocenter Research Study Group. Cost saving effects of a short-term educational intervention entailing lower hypoglycaemic event rates in people with type 1 diabetes and lipo-hypertrophy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;143:320–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2018.07.030.

Trento M, Passera P, Borgo E, et al. A 5-year randomized controlled study of learning, problem solving ability, and quality of life modifications in people with type 2 diabetes managed by group care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(3):670–5. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.3.670.

Trento M, Fornengo P, Amione C, et al. Self-management education may improve blood pressure in people with type 2 diabetes. A randomized controlled clinical trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2020.06.023.

Strollo F, Guarino G, Armentano V, et al. Unexplained hypoglycaemia and large glycaemic variability: skin lipohypertrophy as a predictive sign. Diabetes Res Open J. 2016;2(1):24–32. https://doi.org/10.17140/DROJ-2-126.

Gentile S, Strollo F, Guarino G, et al. Why are so huge differences reported in the occurrence rate of skin lipohypertrophy? Does it depend on method defects or on lack of interest? Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13(1):682–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2018.11.042.

Lee AK, Rawlings AM, Lee CJ, et al. Severe hypoglycaemia, mild cognitive impairment, dementia and brain volumes in older adults with type 2 diabetes: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort study. Diabetologia. 2018;61(9):1956–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-018-4668-1.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The paper was supported by a non-conditioning special grant of the Nefrocenter Research Network and NYX sSartup, Naples, Italy. None of the authors or co-workers received funding or another type of payment for this paper. No Rapid Service Fee was received by the journal for the publication of this article.

Editorial Assistance

Special thanks are due to Paola Murano from Nefrocenter Research Network, for her complimentary editorial assistance, and to Members of the AMD-OSDI Study Group on Injection Technique for critical reading and approval of the manuscript.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

SG and FS prepared and wrote the paper. ES, TDC, GG, GM, AF, GC, SC, MP, MRI, MC, EM, DO, RS, CR, and SV critically read and approved the paper. All authors checked the data collection, critically assessed the results, and approved the final text. All Collaborators critically read and approved the final text.

List of Investigators

Members of the Nefrocenter Research Network and Nyx Start-up Study Group. We thank the following study participants: Nephrologists: S. Meccariello, F. Crisci, F. Leone, R. Marino, M. Romano, G. Cristiano, E. Riccio, F. D'Anna, F. Borghesi, L. Di Gennaro, I. Raiola, A.M.La Manna, M. Cicala, P. Boccia, G. Garofalo, T. Castellano, V. Fimiani, A. Girone, A. Angelino, R. Di Livio, S. Celentano, L. Petruzzelli, L. Annichiarico, A. Cuomo, G. Latte, S. Oliviero, I. Capuano, L. Scarpati, G. Lubrano, L. Giordano, R. Sorrentino, M. Di Monte, F.A. Savino, M.L. Abategiovanni, P. Vendemia, A. Caiazza, A. Scarfato, A. Visone, D. Porpora, R. Mazzarella, C. Botta, O. Di Gruttola, L. Sorrentino, S. Kseniya, S. Vitale I. Cupic, V. Di Stazio, E. Satta, G. Monte, G. Barbuto, F. D'Errico, A. Ciccarelli, E. Verrillo, M. Nappo, A. De Maio, P. Miano, E. Trapanese, G. Brengola, R. Reggio, T. Pagano, N. Crispino, P. Napolitano, R.Cipriano, F. Secondino, Mercogliano, F. Salemi, C. Alfarone, G. Romano, L. Di Leva, R. Barretta. Diabetologists: S. Gentile, G. Guarino, F. Strollo, A. Vetrano, C. Martino, A. Fasolino, MR. Improta, G. Cozzolino, M. Corigliano, C. Brancario, A. Sellere, C. Lamberi, A, Vecchiato. Nurses: V. Morgillo, V. Morgillo, M. Fusco, A. Cimmarosa, M. Brida, A. Guerra, P. Spallieri, P. Cioffi, G. Massaro, C. Romano, R. Apuzzo, A. Cherillo, G. Erbaggio, G. Indaco, L. Manzo, E. Menna, A. Izzo, A. Di Matola, F. Fontanella, M. Puce, G. Fierro, E. Russo, A. Pascarella, A. Di Nardo, A. Bartiromo, T.J. Pazdior, A. Palmiero, E. Ruotolo, R.V. Amoroso, O. Belardo, P. Como, M.T. Natale, L. Erpete, A. Occhio, P.P. Tignola, M. Capasso, F. Barbaro, L. Erpete, S. Milano, M. Strazzulli, A. D'Errico, M.E. Toscano, C. Cirillo, C. Tabacco, A. Stasio, D. Palmeri, M.A. De Vita, A. Auletta, G. Cozzolino, M. Migliaccio, A. Iannone, I. Silvestri, V. Bianco, G. Barrella, T. Conturso, T. Cesarini, O, Ferraro, M. Festinese, L. Bellocchio, V. Pettinati, G. Felaco, E. Ebraico, M. De Lucia, A.M. Mandato, G. Di Maio, M. Cicchella, E. Cicchella, G. Casoria, A. Ricuperati, G. Calabrese, F.M. Isola, M.A. Cesarano, M. Di Riso, M.J. Mlynarska, L. Ambrosino, H. Buska, G. Esposito, V. Esposito, A. Pandolfo, V. D'Esculapio, A. De Costanzo, S. Caso, I. Kropacheva, A. Casaburo, A. Pellino, A. Rainone, C. Gigante, L. Imbembo, T. Carrara, P. Alibertini, L. Bottiglieri, C. D'Elia, C. Montesarchio, B. Jeschke, Z, Matusza, L. Orropesa, M. Vitale, M. Roselli, G. Buonocore, M. Siani, C. Giove, E. Petrone, F. Russo, A. Salsano, M. Agrisani, D. Giordano, A. Crispino, S. De Felice, G. Garofalo, D. Doriano, E. Di Virgilio, G. Fiorenza, I. Mattiello, L. Gala, R. Erricchiello, L. De Micco, I. Fioretti, R. Gladka, D. Mannato, T. Esposito, A. Schettino, R. Riccio, A. Allocca, G. Rusciano, C. Imbimbo, G. Ummarino, G. Fiorenza, G. Salzano, E. De Vincentis, I. Mattiello, P. Ferrante, V. Passa, A. Siani, A. Pastore, M. Battipaglia, G. Martone, E. Della Monica, G. Bernardinelli, D. Battipaglia. Nutritionist: T. Della Corte.

Members of the AMD-OSDI Study Group: S. De Riu, N. De Rosa, G. Grassi, G. Garrapa, L. Tonutti, K. Speese, L. Cucco, M.T. Branca, and A. Botta.

Disclosures

Sandro Gentile, Giuseppina Guarino, Teresa Della Corte, Giampiero Marino, Alessandra Fusco, Gerardo Corigliano, Sara Colarusso, Marco Piscopo, Maria Rosaria Improta, Marco Corigliano, Emilia Martedì, Domenica Oliva, Viviana Russo, Rosa Simonetti, Ersilia Satta, Carmine Romano, Sebastiano Vaia, and Felice Strollo have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was conducted in conformance with good clinical practice standards and was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki 1975, as revised in 2008. It was approved by Vanvitelli University, Naples, Italy (Trial registration number 172–11:12.2019) and by all of the ethics committees of the centers participating in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work was conducted on behalf of the Association of Italian Diabetologists–Italian Diabetology Health Operators (AMD-OSDI) Study Group on Injection Techniques, and the Nefrocenter Network and Nyx Start-up Study Group. A list of study collaborators and study investigators can be found in the Acknowledgements section.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gentile, S., Guarino, G., Della Corte, T. et al. Lipohypertrophy in Elderly Insulin-Treated Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Ther 12, 107–119 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00954-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00954-3