Abstract

With the recognition that most global environmental problems are a result of human actions, there is an increasing interest in approaches which have the potential to influence human behaviour. Images have a powerful role in shaping persuasive messages, yet research on the impacts of visual representations of nature is a neglected area in biodiversity conservation. We systematically screened existing studies on the use of animal imagery in conservation, identifying 37 articles. Although there is clear evidence that images of animals can have positive effects on people’s attitudes to animals, overall there is currently a dearth of accessible and comparable published data demonstrating the efficacy of animal imagery. Most existing studies are place and context-specific, limiting the generalisable conclusions that can be drawn. Transdisciplinary research is needed to develop a robust understanding of the contextual and cultural factors that affect how animal images can be used effectively for conservation purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Most global environmental problems are a result of human actions (Amel et al. 2017; Green et al. 2019). From reducing demand for illegally traded wildlife products to promoting the use of renewable energy sources, tackling today’s major environmental threats comes down to influencing human behaviour. In recognition of this, the biodiversity conservation field has moved beyond the biological sciences and has incorporated the social sciences and humanities (Bennett et al. 2016; Teel et al. 2018). Researchers are now attempting to understand the cognitive, social, and motivational processes that inform behavioural models to provide insights into appropriate approaches for effective behaviour change (Schultz 2014; Reddy et al. 2016). This involves the use of a variety of theoretical and applied perspectives to quantify the non-material relationships between humans and wildlife (Echeverri et al. 2018).

Experiences of nature can have beneficial effects on a range of pro-conservation variables (as well as personal well-being), such as connectedness with nature and pro-environmental attitudes (Kellert 2002; Lumber et al. 2017). A sense of connection with nature through the formation of an affective and/or cognitive relationship is believed to create an appreciation and value for all life, transcending a utilitarian view of nature (Lumber et al. 2017). With increasing urbanisation, however, these direct experiences of nature are becoming less common, a disconnect that is particularly concerning considering the rapid urbanisation in biodiversity hotspots (Kellert 2002; Cohen 2006; Güneralp et al. 2015). Although there is increasing effort to make urban environments less harmful to wildlife, species are still being lost at an alarming rate and it is vital that we use every tool at our disposal to foster connections between people and wildlife in aid of conservation (Wachsmuth, Cohen and Angelo 2016; Dirzo et al. 2014).

There is increasing interest in approaches to change human behaviour, particularly the use of marketing techniques (Veríssimo 2019). Social marketing has been recognised as an applied conservation social science (Bennett et al. 2017) and the Society for Conservation Biology has now a working group dedicated to conservation marketing (Veríssimo 2019). Social marketing is not necessarily a panacea for conservation, but it can provide valuable guidance in designing effective behavioural interventions to be used in conjunction with other approaches that may be needed to catalyse individual, social, and political change (Corner and Randall 2011). Much of the research and discussion in this area so far has centred on the efficacy of different narratives and contextual effects. This has included work on framing of messages, messenger effects, and emotionalisation, integrating research from fields such as human wildlife conflict, science communication, and environmental education (Larson 2005; Draheim et al. 2011; Flemming et al. 2018; Veríssimo et al. 2018). However, despite the adage “a picture is worth a 1000 words”, there has been less investigation into the potential impacts of visual representations of wildlife. The superiority of pictures over text when it comes to information retention is long-established, as it is thought to engage deeper levels of semantic cognitive processing (Shepard 1967; Whitehouse et al. 2006; Hockley 2008). However, in spite of the substantial development of visual communication research in the past decade (see for example Huddy and Gunnthorsdottir 2000; Flemming et al. 2018), there is less research done on visual representations than on textual analysis (Göransson and Fagerholm 2018).

In many ways, society has become an experience economy organised around attention, and with the advent of colour printing and the internet, there is an abundance of visual imagery content (Schroeder 2006; Göransson and Fagerholm 2018). Images that are emotive and vivid have a powerful role to play in shaping persuasive messages (Joffe 2008). They can draw viewers in and aid in recall of important messages (Graber 1990), interacting with prior values and attitudes to shape affective and cognitive reactions (Domke et al. 2002). We respond to imagery directly, experiencing it in terms of emotions, mood, and intuitions (Branthwaite 2002). Images can be considered a convention-based symbolic system, a sophisticated form of visual rhetoric, with the power to transform our collective sensibilities (Scott 1994; Starrett 2003). In recognition of this, fields such as visual social semiotics use qualitative techniques and critical analysis to understand how images are deployed to convey certain meanings (Aiello 2006; Schroeder 2006). Sensory theories of visual communication, such as gestalt (perception of the whole rather than perceptions of individual parts) and constructivism (viewers construct images with quick eye movements combine to build a picture), attempt to explain how the brain processes visual cues such as colour or depth to help us understand why different images attract or distract us (Lester 2013).

Images are used by conservation organisations and the media to construct truths and communicate ideas (SeppÄNen and VÄLiverronen 2003; Hansen and Machin 2013; Göransson and Fagerholm 2018). Although the creation of symbolic representations of nature is ancient, the opportunities provided by technologies we have to reach people through the mass media are relatively new (Kellert 2002). Researchers have found that seeing pictures of nature may not be as effective as contact with actual nature, but they can have similar benefits and help the public to visualise abstract scientific concepts like biodiversity (SeppÄNen and VÄLiverronen 2003; Brooks et al. 2017). However, we need to think carefully about the types of images we use and the messages we are sending. Commonly used climate change symbols such as polar bears and melting ice caps, for instance, may be easily recognised, but frame climate change as a far-away issue, remote from everyday behaviour (Chapman et al. 2016). Rigorous evaluation is needed to empirically validate the methods that are used to change behaviour across different contexts, as there can often be unexpected results (Thomas-Walters and Raihani 2017).

This review will systematically screen existing studies on the use of animal imagery to foster conservation connections. Although many in situ conservation issues are best addressed through the management of habitats rather than single species, we have chosen to focus on images of animals specifically as they are most often used as conservation flagships both for behaviour change and for fundraising purposes (Simberloff 1998; Smith and Sutton 2008). Where there is sufficient data, we investigate the human emotional and cognitive response to images of animals, and how this varies across cultures, geographies, and demographic groups. We focus on where evidence is lacking and make recommendations for future research. This will help researchers and practitioners to assess the current scientific evidence when formulating conservation behaviour change interventions, and identify priority areas for further study.

Methods

We searched two bibliographic databases Scopus and Web of Knowledge using the search strings given in Table 1. Searches were only undertaken in English and were not restricted by publication date. As these academic bibliographic databases do not contain grey literature (research produced by organisations outside of the traditional academic publishing channels), Google Scholar was also searched using the search strings given in Table 2. In addition, we sent a callout to approximately 250 members of the Society for Conservation Biology Conservation Marketing and Engagement, and Social Science Working Groups via email, and 2685 followers on Twitter.

Once the articles captured through the searches were compiled and duplicates removed, the titles and abstracts were screened and categorised according to the inclusion criteria (Table 3). Where there was doubt about whether or not an article met the inclusion criteria, it was retained for assessment during the full- text screening. Once documents had been screened on the basis of their titles and abstracts, all reasonable efforts were made to obtain full-text electronic or paper copies of the documents, including emailing corresponding authors. Articles which had passed the title and abstract screening but for which we were unable to obtain full-text copies were excluded, although this was only one study (Shuttleworth 1980). We then used the bibliographies of the articles returned from our database search to identify further relevant studies during the full-text screening.

Results

We identified 38 papers that empirically tested people’s responses to images of animals (Fig. 1). Full references for each paper can be found in Appendix S2.

Flow diagram illustrating articles retrieved in initial search and articles included following subsequent screening and full-text assessment. Diagram stages adapted from PRISM guidance (Moher et al. 2009)

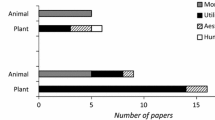

The effects of a range of different visual media were examined, including documentaries, photography exhibitions, television commercials, media campaigns, and popular movies (Fig. 2). The majority focused on still (68%) images (photographs, drawings, etc.) rather than moving ones (documentaries, commercials, etc.), and realistic (92%) rather than illustrated. In terms of geographic representation, North America and Europe are the most studied cultures with 27 articles (73%), whereas Africa and South America had some of the fewest articles for their geographic extent. We found few articles prior to 1999 with a substantial increase after 2010. In addition, we identified a further 18 papers which looked at how preferences for visual attributes of species varied which we used to inform the later section on the relationship between human preferences and aesthetic appeal.

Discussion

There is currently a dearth of accessible and comparable published data demonstrating the efficacy of animal imagery. We identified very few studies looking at the topic (Fig. 1) and most existing studies are place and context-specific, limiting the generalisable conclusions that can be drawn. Important variables that influence responses to visual conservation messages include culture, age, gender, education, and degree of urbanisation. Although some researchers have specifically examined the connections between visual triggers and conservation outcomes, others were interested in a more general sensitisation of participants to conservation. Still others only looked at the relationship between visual cues and animal-oriented behaviour, disassociated from conservation outcomes. Due to the highly disparate nature of the studies, it was not possible to organise the review by response variables, though we do identify any pro-conservation variables studied where applicable.

Some clear lessons do emerge, however. Images of animals can have positive effects on people’s attitudes to animals, altering their emotional responses and willingness to protect them (Kalof et al. 2011; Štefaniková and Prokop 2013; Kalof et al. 2016). Aesthetic appeal is a major contributor to these impacts. There are links between the amount of exposure to wildlife media and the way people behave and feel towards conservation, although the mechanism of this relationship is unclear. However, the literature is fairly disparate. The current research is not concentrated in areas where biodiversity is concentrated, and many types of images have been neglected, e.g. moving visual images such as videos.

Comparing imagery styles and presentation

One aspect that has received relatively little attention in the literature is comparisons of different formats of engagement, such as different documentary styles or classroom lectures, with most studies focusing on the effects of photographs alone (see Fig. 2a). Both viewing a Cousteau Society documentary on marine mammals and listening to a science teacher’s presentation of the documentary’s script improved knowledge and attitudes about marine mammals for American adolescents (Fortner 1985). One study compared the effects of two different styles (traditional versus non-verbal) of nature documentaries featuring insects on Greek 12-year-olds (Barbas et al. 2009). Although both styles were equally effective in increasing empathetic feelings towards the environment, the non-verbal documentary was superior at developing environmental knowledge. No hypothesis was put forwards as to why the absence of a verbal or written narrative actually increased knowledge, and the neglect of any behavioural measures limits the usefulness of these investigations. It also raises questions regarding the effect of cultural context – would similar results have been found with Kenyan or American school children? There is no guarantee that these findings translate across cultures, limiting the general recommendations that can be made as a result of this research.

Other studies have tested the likeability and willingness to protect animals across different formats, such as cartoons and photographs. For example, adult Filipinos were significantly more willing to protect their national bird, the Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi) when shown coloured rather than black-and-white photographs (Labao et al. 2008). In another study, anthropomorphised cartoon illustrations rather than photographs may also increase interest and likeability (Louch et al. 1999; Osinski 2017).

When animal representations are placed in a visual context that is more typically associated with human representation, a form of portrait photography, perceptions of animals as individuals with a personality are enhanced (Kalof et al. 2011, 2016). This has resulted in both Canadian college students and visitors to a French museum experiencing an increase in feelings of kinship with animals after viewing (Kalof et al. 2011, 2016).

The species effect - aesthetics, anthropomorphism, and charisma

Aesthetics is an important factor in how people engage with images of animals, and people are more willing to support an animal they find aesthetically pleasing (Gunnthorsdottir 2001; Knight 2008; Liordos et al. 2017). This is not particularly surprising as a bias in conservation towards flagship species, generally charismatic vertebrate, has long been acknowledged (Clucas et al. 2008; Smith and Sutton 2008; Ducarme et al. 2013). Online experiments show that conservation campaigns featuring appealing species (e.g. a polar bear) will receive higher donations compared to ones featuring unappealing species (e.g. a stonefly) (Thomas-Walters and Raihani 2017; Veríssimo et al. 2017). However, it is worth noting that contrary to this evidence, in an analysis of an offline large-scale fundraising campaign no effect of appeal or familiarity of species was found on monetary donations (Veríssimo et al. 2018). These differences in results may be due to differences in methods, limiting comparability.

There has been some research into what exactly are the traits that influence physical attractiveness in a species, such as a preference for brightly coloured animals and similarity to humans (i.e. anthropomorphism) (Barua et al. 2012; Prokop and Fančovičová 2013; Breuer et al. 2015). As an example of anthropomorphism, greater body mass and bigger and forward-facing eyes have been found to guide preferences (Tisdell and Wilson 2006; Martín-López et al. 2007; Knegterin et al. 2010; Veríssimo et al. 2018). Similarly, a human preference for baby schema may influence judgement of bird silhouettes also, with short necks and big eyes being the most appealing traits (Lišková and Frynta 2013). There is a limited evidence base on which to judge the role of anthropomorphism in influencing behaviour or even attitudes towards biodiversity, however, particularly in the case of biological groups such as plants that commonly receive less public attention (Root-Bernstein et al. 2013).

Although there is clear evidence that humans are influenced by aesthetic appeal, we should not necessarily focus campaigns on a single subset of animals. Too much focus on appealing, charismatic animals may lead to a neglect of other threatened species and contribute to conservation issues (Simberloff 1998; Fazey et al. 2005; Douglas and Winkel 2014). In addition, understanding factors that compensate for a lack of aesthetic appeal is important because many endangered species are not ideal flagships. For example, in one Swiss city, familiarity and ecological utility meant that the clover stem weevil (Ischnopterapion virens) outperformed the great spotted woodpecker as a flagship species for a hypothetical conservation project (Home et al. 2009). Other predictors of support include rarity and endangered status, suggesting that these are key features to be highlighted in any accompanying text (Gunnthorsdottir 2001; Angulo and Courchamp 2009; Schlegel and Rupf 2010). Including more information or increasing the marketing effort for an undesirable species can increase support, relative to other animals (Veríssimo et al. 2017; Curtin and Papworth 2018). Research on appeals featuring human subjects shows that people demonstrate a greater willingness to help identified individuals rather than unidentified, or statistical, victims (Jenni and Loewenstein 1997). However, this effect does not seem to translate to appeals featuring wildlife, where assigning individual animal names and identities does not increase donations (Thomas-Walters and Raihani 2017). One reason for this could be the authenticity of identified victims in charitable appeals—it may be easier to believe that an orphaned girl called Juanita genuinely exists and needs your help than Rosie the polar bear.

Animal imagery in the media

There is a link between the amount of time spent watching wildlife programmes and the way people behave and feel towards the environment. For example, American adults and Hong Kong adolescents who watch more wildlife and environmental programmes perform more conservation behaviours and believe more in valuing nature for itself, rather than any utilitarian purpose (Holbert et al. 2003; Clark 2006; Lee 2011). This is not necessarily a causal relationship, however, and it is important to be aware that any potential causality could run both ways. Given that environmental concern is a strong positive predictor of nature show consumption (Holbert et al. 2003), it could simply be the case that those who are already willing to change their behaviour are more likely to be watching nature programmes. To investigate any causal relationships a robust impact evaluation study design would be required, as comparing the values and behaviours of those who watch wildlife media with those who do not is an invalid approach (Veríssimo et al. 2018). One alternative would be to explore behaviour in a lab game or on outcomes that are easily measured such as ‘nature connectedness’ or donations to conservation immediately following exposure (Arendt and Matthes 2016; Barbas et al. 2009; Zelenski et al. 2015).

Whether the portrayal of animals in popular culture has positive, negative, or neutral effects on people’s behaviour and attitudes towards conservation is debated, and the evidence is inconclusive and often lacking. Despite multiple claims in the media that Finding Nemo and the Harry Potter film franchise led to an increase in demand for pet clown fish and owls, impact evaluations find no evidence to support this narrative (Megias et al. 2017; Militz and Foale 2017). It has also been suggested that viral videos could also affect demand for wild animals, and one study analysed the YouTube comments on a video of a slow loris being tickled (Nekaris et al. 2013). The proportion of comments about wanting a pet loris decreased significantly over time, and more viewers expressed awareness about the inhumane removal of slow lorises’ teeth in the pet trade. The video itself was not educational, but the forum allowed for the spread of conservation and ecological facts. This is an example of the ad hoc nature of much of the available data, and the difficulty it poses for drawing conclusions. Whether a proportionate decrease in comments reflects an actual decrease in desire for a pet loris or just a change in social norms cannot be ascertained.

Animals in anthropocentric settings

Showing animals in a context with humans generally has a negative effect on specific aspects of human–animal relationships. Americans feel greater continuity (viewed animals and humans as more similar) towards a companion animal that has been photographed alone (Carter 2011) and are less likely to believe that primates are threatened and are more likely to desire them as a pet if they are shown with a human nearby (Ross et al. 2011; Leighty et al. 2015). This may be because people are better able to connect with a companion animal when photographed alone by picturing themselves with it, while chimpanzees are perceived as less dangerous and more manageable when in contact with humans (Leighty et al. 2015). They are also more likely to desire chimpanzees as pets and less likely to donate to a conservation charity after watching a commercial featuring an “entertainment” chimpanzee, e.g. working in an office, rather than a chimpanzee conservation commercial or footage of wild chimpanzees (Schroepfer et al. 2011). However, a human setting is not always harmful—most American undergraduates expressed positive attitudes towards an image of a coyote lying on a human bed, potentially because they were reminded of a pet dog (Draheim et al. 2011). The framing of similarities between humans and animals affects our moral concern for others and comparing animals to humans can reduce speciesism (although comparing humans to animals may have negative effects; Costello and Hodson 2008; Bastian et al. 2012). It is important to note that variables such as human–animal continuity do not necessarily translate to pro-conservation behaviours, presumably the end-goal of most conservation campaigns, and that these studies were all conducted on American audiences. In countries where dogs do not hold such a central place in a family’s home, or where people have actually had contact with threatened species like chimpanzees, the effects may be very different.

Emotive imagery

Studies in health psychology and climate change show that fear appeals need to be coupled with constructive information that enable people to respond, therefore avoiding the risk of overwhelming their target audience. Fear appeals are frequently used in social marketing, as they can help form behavioural intentions by causing people to perceive themselves as vulnerable (Das et al. 2003; de Hoog et al. 2005; Moser and Dilling 2007). However, they can also overwhelm viewers, resulting in a disengagement from the message through denial of the problem, and apocalyptic messaging can lead people to question whether the messenger is trustworthy (Witte and Allen 2000; Stoll-Kleemann et al. 2001; Moser and Dilling 2007). We found only one study in conservation which examined the use of images in a fear appeal, where American undergraduates were shown a video about whaling (Shelton and Rogers 1981). Behavioural intentions to help were higher when noxiousness (e.g. gory scenes of bodily injury to whales) and efficacy (e.g. scenes of a Greenpeace crew successfully saving whales) were increased.

Limited evidence exists that shocking imagery may be more effective at eliciting donations. For example, when asked to split donations between two photographs of rhinos, British adults gave more money to the image that was more upsetting and gory (Pestridge 2017). A picture of a dead and bloodied rhino was chosen over an alive but visibly injured one. However, the study failed to investigate contextual variables, such as culture, that could affect donation decisions. For instance, people who were more highly educated actually donated less to the more shocking image. This limits the broader usefulness of the findings. When humans are the subject of a charitable appeal, the display of negative emotions can affect the emotional intensity generated by images and result in significantly larger donations (Burt and Strongman 2005). Whether this extends to animal victims has yet to be studied.

Attitudes have both an affective and a cognitive component and addressing both components might be the most effective method of changing attitudes (Pearson et al. 2011). Empathy is a strong predictor of prosociality, and researchers have been exploring ways to increase empathy towards different victims (Schultz 2000). For example, when Spanish undergraduates viewing images of nature being harmed (either a bird or a tree) were instructed to take the perspective of the object being harmed rather than remain objective, their willingness to help nature increased (Berenguer 2007). Innate threat responses, however, e.g. in reaction to viewing images of snakes, spiders, or animals in a dangerous pose, interfere with the capacity to feel empathy and compassion (Davey 2011; Štefaniková and Prokop 2013; Bertels et al. 2017).

Variation across demographics and cultures

Most studies focused on inhabitants of Europe and North America (see Fig. 2b), limiting comparisons to other nationalities. The only cross-cultural study found considerable overlap in assessment of python and boa beauty in photographs by adults from the Czech Republic and Papua New Guinea (Marešová et al. 2009). However, research from health communication shows that culture can affect the efficacy of a given intervention strategy and has an important role to play in audience segmentation, suggesting an urgent need for more investigation in this area (Kreuter and McClure 2004). Prior attitudes and values of the audience may also influence their receptivity to different messages (Domke et al. 2002). Emotive images of animals have the greatest effect on the most involved environmental supporters, and watching a nature documentary may only increase pro-environmental donation behaviour for viewers who already have a strong sense of connectedness (Huddy and Gunnthorsdottir 2000; Arendt and Matthes 2016). Few significant gender differences were found, with the exception of emotional reactions to different species in children (Schlegel and Rupf 2010; Borgi and Cirulli 2015; Schlegel et al. 2016). Young girls showed greater fear and disgust to images of certain animals, such as spiders, and this was associated with lower levels of affinity. Although a range of ages have been examined (see Fig. 2c), none have attempted to determine whether images of animals affect, for example children differently than adults.

Key recommendations for future research

Studies on the effects of animal images are few but increasing (rt= .455, p = .0003), as shown in Fig. 2d, and their designs and objectives are disparate and difficult to compare. Moreover, they have almost exclusively been conducted on a fairly narrow subset of Western audiences (see Fig. 2). Research in behavioural science shows that there is substantial variability in experimental results across populations, and this lack of diversity in research participants is concerning as both culture and education level may be important factors in determining responses to images of animals (Henrich et al. 2010). Attitudes are context-contingent, and there can be large differences between Western and non-Western cultural contexts (Riemer et al. 2014). Exploring how responses to narratives and visuals differs across cultures should be a top priority, which could require a deeper understanding of varying lay theories that people hold about nature. There is scope for transdisciplinary research incorporating fields such as neuroscience, psychology, and social marketing to develop a consolidated understanding of the different contextual and cultural factors that affect how animal images can be used effectively and cross-culturally in social marketing for conservation purposes, including when visual communication is less applicable. An investigation into the rationales used by non-governmental environmental agencies in the design of their campaign materials could also be illuminating.

Finally, we need to move beyond solely assessing attitudes or social media engagement to investigating actual or intended behaviour change. For instance, animal images may increase social media interest in a news story, but it is often unclear whether indicators such as likes, retweets, or even online pledges, actually translate to real-world behaviour changes (Curtin and Papworth 2018; Wu et al. 2018). Changes in knowledge alone are rarely sufficient to affect behaviour, and there is frequently a sizeable gap between intentions and actual behaviour (Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002; Sheeran 2002; Webb and Sheeran 2006). Integrating behavioural theory into campaigns, including drivers such as interpersonal communication, is necessary to achieve behaviour change (Green et al. 2019). Many papers failed to establish causal attribution, instead uncovering correlations between exposure to images of animals and a change in knowledge, attitudes, or behaviour. Very few also attempted to explore the psychological mechanisms behind the variable of interest, to elucidate not just whether a certain image had an effect but also why. The impact of specific image attributes was a relatively neglected area, as is the combination of narratives with images. Improving experimental designs may help us to elicit why an intervention succeeds or fails, and identify the conditions under which any causal effect arises (Baylis et al. 2016). This is an area in which fields such as international development have been leading the way, for example with the use of credible counterfactuals and theory-based evaluation. Conservation science should follow in their footsteps when it comes to adopting best practices in impact evaluation (Banerjee and Duflo 2009; White 2009; Baylis et al. 2016). If the integration of visual media into our daily lives continues to increase, then understanding its use as a tool to communicate the importance of wildlife will become ever more crucial.

References

Aiello, G. 2006. Theoretical advances in critical visual analysis: Perception, ideology, mythologies, and social semiotics. Journal of Visual Literacy 26: 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2006.11674635.

Amel, E., C. Manning, B. Scott, and S. Koger. 2017. Beyond the roots of human interaction: Fostering collective effort toward ecosystem conservation. Science 356: 275–279.

Angulo, E., and F. Courchamp. 2009. Rare species are valued big time. PLoS ONE 4: e5215. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005215.

Arendt, F., and J. Matthes. 2016. Nature documentaries, connectedness to nature, and pro-environmental behavior. Environmental Communication 10: 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2014.993415.

Banerjee, A.V., and E. Duflo. 2009. The experimental approach to development economics. Annual Review of Economics 1: 151–178. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.economics.050708.143235.

Barbas, T.A., S. Paraskevopoulos, and A.G. Stamou. 2009. The effect of nature documentaries on students’ environmental sensitivity: A case study. Learning, Media and Technology 34: 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439880902759943.

Barua, M., D.J. Gurdak, R.A. Ahmed, and J. Tamuly. 2012. Selecting flagships for invertebrate conservation. Biodiversity and Conservation 21: 1457–1476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-012-0257-7.

Bastian, B., S. Loughnan, N. Haslam, and H.R. Radke. 2012. Don’t mind meat? The denial of mind to animals used for human consumption. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38: 247–256.

Baylis, K., J. Honey-Rosés, J. Börner, E. Corbera, D. Ezzine-de-Blas, P.J. Ferraro, R. Lapeyre, U.M. Persson, et al. 2016. Mainstreaming impact evaluation in nature conservation. Conservation Letters 9: 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12180.

Bennett, N.J., R. Roth, S.C. Klain, K. Chan, P. Christie, D.A. Clark, G. Cullman, D. Curran, et al. 2017. Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biological Conservation 205: 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.006.

Bennett, N.J., R. Roth, S.C. Klain, K.M.A. Chan, D.A. Clark, G. Epstein, M.P. Nelson, R. Stedman, et al. 2016. Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conservation Biology 00: 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12788.This.

Berenguer, J. 2007. The effect of empathy in pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Environment and Behavior 39: 269–283.

Bertels, J., C. Bayard, C. Floccia, and A. Destrebecqz. 2017. Rapid detection of snakes modulates spatial orienting in infancy. International Journal of Behavioral Development 42: 381–387.

Borgi, M., and F. Cirulli. 2015. Attitudes toward animals among kindergarten children: Species preferences. Anthrozoos 28: 45–59. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279315X14129350721939.

Branthwaite, A. 2002. Investigating the power of imagery in marketing communication: Evidence-based techniques. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 5: 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750210432977.

Breuer, G.B., J. Schlegel, and R. Rupf. 2015. Selecting insects as flagship species for Beverin Nature Park in Switzerland—A survey of local school children on their attitudes towards butterflies and other insects. Eco.Mont 7: 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1553/eco.mont-7-1s5.

Brooks, A.M., K.M. Ottley, K.D. Arbuthnott, and P. Sevigny. 2017. Nature-related mood effects: Season and type of nature contact. Journal of Environmental Psychology 54: 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.10.004.

Burt, C., and K. Strongman. 2005. Use of images in charity advertising: Improving donations and compliance rates. International Journal of Organisational Behavior 8: 571–580.

Carter, A. 2011. Attitude change regarding animal abuse in adults the effect of education and visual aids. MSc Thesis. University of Central Florida.

Chapman, D.A., A. Corner, R. Webster, and E.M. Markowitz. 2016. Climate visuals: A mixed methods investigation of public perceptions of climate images in three countries. Global Environmental Change 41: 172–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.10.003.

Clark, F.J. 2006. Effects of watching wildlife television on wildlife conservation behavior. PhD Thesis. University of Washington.

Clucas, B., K. McHugh, and T. Caro. 2008. Flagship species on covers of US conservation and nature magazines. Biodiversity and Conservation 17: 1517–1528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-008-9361-0.

Cohen, B. 2006. Urbanization in developing countries: Current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability. Technology in Society 28: 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2005.10.005.

Corner, A., and A. Randall. 2011. Selling climate change? The limitations of social marketing as a strategy for climate change public engagement. Global Environmental Change 21: 1005–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.05.002.

Costello, Kimberly, and Gordon Hodson. 2008. Exploring the roots of dehumanization: The role of animal-human similarity in promoting immigrant humanization. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 13: 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430209347725.

Curtin, P., and S. Papworth. 2018. Increased information and marketing to specific individuals could shift conservation support to less popular species. Marine Policy 88: 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.11.006.

Das, E.H.H.J., J.B.F. De Wit, and W. Stroebe. 2003. Fear appeals motivate acceptance of action recommendations: Evidence for a positive bias in the processing of persuasive messages. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 29: 650–664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203251527.

Davey, G.C. 2011. Disgust: The disease-avoidance emotion and its dysfunctions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 366: 3453–3465.

de Hoog, N., W. Stroebe, and J.B.F. de Wit. 2005. The impact of fear appeals on processing and acceptance of action recommendations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 31: 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271321.

Dirzo, R., H.S. Young, M. Galetti, G. Ceballos, N.J.B. Isaac, and B. Collen. 2014. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 345: 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1251817.

Domke, D., D. Perlmutter, and M. Spratt. 2002. The primes of our times? An examination of the “power” of visual images. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 3: 131–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/146488490200300211.

Douglas, L.R., and G. Winkel. 2014. The flipside of the flagship. Biodiversity and Conservation 23: 979–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-014-0647-0.

Draheim, M.M., L.L. Rockwood, G. Guagnano, and E.C.M. Parsons. 2011. The impact of information on students’ beliefs and attitudes toward coyotes. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 16: 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2011.536911.

Ducarme, F., G.M. Luque, and F. Courchamp. 2013. What are “charismatic species” for conservation biologists? BioSciences Master Reviews 1: 1–8.

Echeverri, A., D.S. Karp, R. Naidoo, J. Zhao, and K.M.A. Chan. 2018. Approaching human-animal relationships from multiple angles: A synthetic perspective. Biological Conservation 224: 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.05.015.

Fazey, I., J. Fischer, and D.B. Lindenmayer. 2005. What do conservation biologists publish? Biological Conservation 124: 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.01.013.

Flemming, D., U. Cress, S. Kimmig, M. Brandt, and J. Kimmerle. 2018. Emotionalization in science communication: The impact of narratives and visual representations on knowledge gain and risk perception. Frontiers in Communication 3: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2018.00003.

Fortner, R.W. 1985. Relative effectiveness of classroom and documentary film presentations on marine mammals. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 21: 115–126.

Göransson, K., and A.-S. Fagerholm. 2018. Towards visual strategic communications: An innovative interdisciplinary perspective on visual dimensions within the strategic communications field. Journal of Communication Management 22: 46–66.

Graber, D.A. 1990. Seeing is remembering: How visuals contribute to learning from television news. Journal of Communication 40: 134–156.

Green, K.M., B.A. Crawford, K.A. Williamson, and A.A. DeWan. 2019. A meta-analysis of social marketing campaigns to improve global conservation outcomes. Social Marketing Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524500418824258.

Güneralp, B., A.S. Perlstein, and K.C. Seto. 2015. Balancing urban growth and ecological conservation: A challenge for planning and governance in China. Ambio 44: 532–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-015-0625-0.

Gunnthorsdottir, A. 2001. Physical attractiveness of an animal species as a decision factor for its preservation. Anthrozoos 14: 204–214. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279301786999355.

Hansen, A., and D. Machin. 2013. Researching visual environmental communication. Journal of Landscape Architecture 7: 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2013.785441.

Henrich, J., S.J. Heine, and A. Norenzayan. 2010. The weirdest people in the world? Behavioural and Brain Sciences 33: 61–135.

Hockley, W.E. 2008. The picture superiority effect in associative recognition. Memory and Cognition 36: 1351–1359. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.36.7.1351.

Holbert, R.L., N. Kwak, and D.V. Shah. 2003. Environmental concern, patterns of television viewing, and pro-environmental behaviors: Integrating models of media consumption and effects. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 47: 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4702.

Home, R., C. Keller, P. Nagel, N. Bauer, and M. Hunziker. 2009. Selection criteria for flagship species by conservation organizations. Environmental Conservation 36: 139. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892909990051.

Huddy, L., and A.H. Gunnthorsdottir. 2000. The persuasive effects of emotive visual imagery: Superficial manipulation or the product of passionate reason. Political Psychology 21: 745–778. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00215.

Jenni, K.E., and G. Loewenstein. 1997. Explaining the “Identifiable Victim Effect”. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 14: 235–257.

Joffe, H. 2008. The power of visual material: Persuasion, emotion and identification. Diogenes 55: 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0392192107087919.

Kalof, L., J. Zammit-Lucia, J. Bell, and G. Granter. 2016. Fostering kinship with animals: animal portraiture in humane education. Environmental Education Research 22: 203–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.999226.

Kalof, L., J. Zammit-Lucia, and J.R. Kelly. 2011. The meaning of animal portraiture in a museum setting: Implications for conservation. Organization and Environment 24: 150–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026611412081.

Kellert, S.R. 2002. Experiencing nature: Affective, cognitive, and evaluative development in children. In Children and nature : Psychological, sociocultural, and evolutionary investigations, ed. P.H. Kahn and S.R. Kellert, 117–151. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3539-9.

Knegterin, E., H.J. Van Der Windt, and A.J.M. Schoot Uiterkamp. 2010. Public decisions on animal species: Does body size matter? Environmental Conservation 38: 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892910000755.

Knight, A.J. 2008. “Bats, snakes and spiders, Oh my!” How aesthetic and negativistic attitudes, and other concepts predict support for species protection. Journal of Environmental Psychology 28: 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.10.001.

Kollmuss, A., and J. Agyeman. 2002. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research 8: 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350462022014540.

Kreuter, M.W., and S.M. McClure. 2004. The role of culture in health communication. Annual Review of Public Health 25: 439–455. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000.

Labao, R., H. Francisco, D. Harder, and F.I. Santos. 2008. Do colored photographs affect willingness to pay responses for endangered species conservation? Environmental & Resource Economics 40: 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-007-9151-2.

Larson, B.M.H. 2005. The war of the roses: Demilitarizing invasion biology. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 3: 495–500.

Lee, K. 2011. The role of media exposure, social exposure and biospheric value orientation in the environmental attitude-intention-behavior model in adolescents. Journal of Environmental Psychology 31: 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.08.004.

Leighty, K.A., A.J. Valuska, A.P. Grand, T.L. Bettinger, J.D. Mellen, S.R. Ross, P. Boyle, and J.J. Ogden. 2015. Impact of visual context on public perceptions of non-human primate performers. PLoS ONE 10: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118487.

Lester, P.M. 2013. Visual communication: Images with messages, 6th ed. Boston: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Liordos, V., V.J. Kontsiotis, M. Anastasiadou, and E. Karavasias. 2017. Effects of attitudes and demography on public support for endangered species conservation. Science of the Total Environment 595: 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.241.

Lišková, S., and D. Frynta. 2013. What determines bird beauty in human eyes? Anthrozoos 26: 27–41. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303713X13534238631399.

Louch, J., E.C. Price, M. Esson, and A.T.C. Feistner. 1999. The effects of sign styles on visitor behaviour at the orang-utan enclosure at Jersey zoo. Dodo: Journal of the Wildlife Preservation Trusts 35: 134–150.

Lumber, R., M. Richardson, and D. Sheffield. 2017. Beyond knowing nature: Contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLoS ONE 12: e0177186.

Marešová, J., K. Antonín, and D. Frynta. 2009. We all appreciate the same animals: Cross-cultural comparison of human aesthetic preferences for snake species in Papua New Guinea and Europe. Ethology 115: 297–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2009.01620.x.

Martín-López, B., C. Montes, and J. Benayas. 2007. The non-economic motives behind the willingness to pay for biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation 139: 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2007.06.005.

Megias, D.A., S.C. Anderson, R.J. Smith, and D. Veríssimo. 2017. Investigating the impact of media on demand for wildlife: A case study of Harry Potter and the UK trade in owls. PLoS ONE 12: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182368.

Militz, T.A., and S. Foale. 2017. The “Nemo Effect”: Perception and reality of finding Nemo’s impact on marine aquarium fisheries. Fish and Fisheries. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12202.

Moher, D., A. Liberatie, J. Tetzlaff, D.G. Altman, and T.P. Group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 6: e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Moser, S.C., and L. Dilling. 2007. Creating a climate for change: Communicating climate change and facilitating social change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nekaris, B.K.A.I., N. Campbell, T.G. Coggins, E.J. Rode, and V. Nijman. 2013. Tickled to death: Analysing public perceptions of “cute” videos of threatened species (slow lorises—Nycticebus spp.) on Web 2.0 Sites. PLoS ONE 8: e69215. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069215.

Osinski, B. 2017. What’s the draw: Illustrating the impacts of cartoons versus photographs on attitudes and behavioral intentions for wildlife conservation. PhD Thesis. Purdue University.

Pearson, E., J. Dorrian, and C. Litchfield. 2011. Harnessing visual media in environmental education: Increasing knowledge of orangutan conservation issues and facilitating sustainable behaviour through video presentations. Environmental Education Research 17: 751–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.624586.

Pestridge, E. 2017. The role of shock imagery in non-governmental organisations and media campaigns surrounding the rhino poaching crisis. MSc Thesis. University of Kent.

Prokop, P., and J. Fančovičová. 2013. Does colour matter? The influence of animal warning coloration on human emotions and willingness to protect them. Animal Conservation 16: 458–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12014.

Reddy, S.M.W., J. Montambault, Y.J. Masuda, A. Gneezy, E. Keenan, W. Butler, J.R. Fisher, and S.T. Asah. 2016. Advancing conservation by understanding and influencing human behavior. Conservation Letters. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12252.

Riemer, H., S. Shavitt, M. Koo, and H.R. Markus. 2014. Preferences don’t have to be personal: Expanding attitude theorizing with a cross-cultural perspective. Psychological Review 121: 619–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037666.

Root-Bernstein, M., L. Douglas, A. Smith, and D. Veríssimo. 2013. Anthropomorphized species as tools for conservation: Utility beyond prosocial, intelligent and suffering species. Biodiversity and Conservation 22: 1577–1589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-013-0494-4.

Ross, S.R., V.M. Vreeman, and E.V. Lonsdorf. 2011. Specific image characteristics influence attitudes about chimpanzee conservation and use as pets. PLoS ONE 6: 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022050.

Schlegel, J., G. Breuer, and R. Rupf. 2016. Local insects as flagship species to promote nature conservation? A survey among primary school children on their attitudes toward invertebrates. Anthrozoos 28: 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2015.11435399.

Schlegel, J., and R. Rupf. 2010. Attitudes towards potential animal flagship species in nature conservation: A survey among students of different educational institutions. Journal for Nature Conservation 18: 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2009.12.002.

Schroeder, J.E. 2006. Introduction to the special issue on aesthetics, images and vision. Marketing Theory 6: 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593106061886.

Schroepfer, K.K., A.G. Rosati, T. Chartrand, and B. Hare. 2011. Use of “entertainment” chimpanzees in commercials distorts public perception regarding their conservation status. PLoS ONE 6: 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026048.

Schultz, P.W. 2000. Empathizing with nature: The effects of perspective taking on concern for environmental issues. Journal of Social Issues 56: 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00174.

Schultz, P.W. 2014. Strategies for promoting pro-environmental behavior. European Psychologist 19: 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000163.

Scott, L.M. 1994. Images in advertising: The need for a theory of visual rhetoric. Journal of Consumer Research 21: 252. https://doi.org/10.1086/209396.

SeppÄNen, J., and E. VÄLiverronen. 2003. Visualizing biodiversity: The role of photographs in environmental discourse. Science as Culture 12: 59–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950543032000062263.

Sheeran, P. 2002. Intention-behaviour relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology 12: 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470013478.ch1.

Shelton, M.L., and R.W. Rogers. 1981. Fear-arousing and empathy-arousing appeals to help: The pathos of persuasion. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 11: 366–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1981.tb00829.x.

Shepard, R.N. 1967. Recognition memory for words, sentences, and pictures. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 6: 156–163.

Shuttleworth, S. 1980. The use of photographs as an environmental presentation medium in landscape studies. Journal of Environmental Management 11: 61–67.

Simberloff, D. 1998. Flagships, umbrellas, and keystones: Is single-species management passe in the landscape era? Biological Conservation 83: 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(97)00081-5.

Smith, A.M., and S.G. Sutton. 2008. The role of a flagship species in the formation of conservation intentions. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 13: 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200701883408.

Starrett, G. 2003. Violence and the rhetoric of images. Cultural Anthropology 18: 398–428. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.2003.18.3.398.

Štefaniková, S., and P. Prokop. 2013. Introduction of the concept of adaptive memory to science education: Does survival threat influence our knowledge about animals? Journal of Environmental Protection and Ecology 14: 1403–1414.

Stoll-Kleemann, S., T. O’Riordan, and C.C. Jaeger. 2001. The psychology of denial concerning climate mitigation measures: Evidence from Swiss focus groups. Global Environmental Change 11: 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(00)00061-3.

Teel, T.L., C.B. Anderson, M.A. Burgman, J. Cinner, D. Clark, R.A. Estévez, J.P. Jones, T.R. McClanahan, et al. 2018. Publishing social science research in Conservation Biology to move beyond biology. Conservation Biology 32: 6–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/COBI.13059.

Thomas-Walters, L., and N.J. Raihani. 2017. Supporting conservation: The roles of flagship species and identifiable victims. Conservation Letters 10: 581–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12319.

Tisdell, C., and C. Wilson. 2006. Information, wildlife valuation, conservation: Experiments and policy. Contemporary Economic Policy 24: 144–159. https://doi.org/10.1093/cep/byj014.

Veríssimo, D. 2019. The past, present, and future of using social marketing to conserve biodiversity. Social Marketing Quarterly 25: 3–8.

Veríssimo, D., H.A. Campbell, S. Tollington, D.C. Macmillan, and R.J. Smith. 2018. Why do people donate to conservation? Insights from a “real world” campaign. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191888.

Veríssimo, D., G. Vaughan, M. Ridout, C. Waterman, D. MacMillan, and R.J. Smith. 2017. Increased conservation marketing effort has major fundraising benefits for even the least popular species. Biological Conservation 211: 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.04.018.

Wachsmuth, D., D. Cohen, and D. Angelo. 2016. Expand the frontiers of urban sustainability. Nature 536: 391–393. https://doi.org/10.1038/536391a.

Webb, T.L., and P. Sheeran. 2006. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin 132: 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249.

White, H. 2009. Theory-based impact evaluation: Principles and practice (Working Paper 3). The International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie). http://www.3ieimpact.org/media/filer_public/2012/05/07/Working_Paper_3.pdf.

Whitehouse, A.J.O., M.T. Maybery, and K. Durkin. 2006. The development of the picture-superiority effect. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 24: 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151005X74153.

Witte, K., and M. Allen. 2000. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior 27: 591–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810002700506.

Wu, Y., L. Xie, S.L. Huang, P. Li, Z. Yuan, and W. Liu. 2018. Using social media to strengthen public awareness of wildlife conservation. Ocean and Coastal Management 153: 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.12.010.

Zelenski, J.M., R.L. Dopko, and C.A. Capaldi. 2015. Cooperation is in our nature: Nature exposure may promote cooperative and environmentally sustainable behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology 42: 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.01.005.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by the National Geographic Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas-Walters, L., McNulty, C. & Veríssimo, D. A scoping review into the impact of animal imagery on pro-environmental outcomes. Ambio 49, 1135–1145 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01271-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01271-1