Abstract

Nationalism has emerged to be discussed in this modern era due to the emergence of a globalized society. Its delivery structure of nationalism message is significant to be investigated due to its impact on the self-determination of a nation so that nationalism spreads among civil society. In the Indonesian context, discussions of Indonesia’s Independence Day arise as a response to this self-determination. Its discussion came up in a face-to-face conversation, as well as on Twitter through the #HUTRI76 network. As a microblogging platform, Twitter was able to facilitate discussion of Indonesian in articulating their Independence Day. The concept of nationalism was utilized to sharpen the analysis. Hence, the social network analysis method has been applied to explore various metrics in the #HUTRI76 Twitter network. The results showed some influencers who varied in their profession, emerged and played a role in sparking discourse on Indonesia’s Independence Day. The discussion of Indonesian Independence Day on Twitter was a reproduction message of the government. Moreover, users engaged the varied media to cross-posting their messages as regards Indonesia’s Independence Day, which means Twitter acts as a hub through hyperlinks embedded in tweets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Even though the golden era of nationalism ideology is predicted to end at the end of the twentieth century, unexpectedly, this ideology has returned to attention and emerged as a massive movement in many countries. Events such as the Russia-Ukraine war (Breuilly and Halikiopoulou 2022; Knott 2022; Kuzio 2022), the shooting of Shinzo Abe in Japan (Duffy 2022; Magcamit 2019; Wingfield-Hayes 2022), Brexit in Britain (Brown 2017; Gusterson 2017; Mcewen 2022; Roth 2018; Stephens 2019), the election of Donald Trump in the USA (Bieber 2018; Giroux 2017; Restad 2020; Schertzer and Woods 2020), and the election of nationalist leaders in many parts of the world have aroused civil society movements in these countries to express their nationalism openly to the public. Specifically, in Indonesia, the election of Joko Widodo, a figure who is considered to represent the nationalist orientations (Madu, 2017) and nationalist economist ideology (Gede Wahyu Wicaksana 2019), as president for two terms (2014–2024) and the victory of PDIP, which is a nationalist party, for two terms (2014–2024) in the legislative elections, shows the beginning of the new era of nationalism rising (Ramdhani and Anggraini 2021). In recent times, the existence of nationalism ideology is constantly increasing and being felt in many countries. Even Bieber said that nationalism acts like air, it is omnipresent and its behavior is abstruse (Bieber 2018).

Various moments are considered to trigger the emergence of the nationalist movement (Merriman 2020; Paasi 2016; Visoka 2020; Z. Wang 2021; Żuk and Żuk 2022). One of the important moments to be discussed in Indonesia around nationalism is Indonesia’s Independence Day. Independence Day can be seen as an assertion of a nation-state or as a sustaining of collective consciousness, reminiscent of memories that created nation-building (Akuupa and Kornes 2015), and constitute collective memory (Kook 2006), or pay tribute to the beginnings of independence (Nyyssönen 2009). As Independence Day is important and deserves scholarly consideration, it was set in a longer historical time frame and broader geographical perspective. Indeed, Independence Day has more variation in practice than is generally recognized (Cannadine 2008), revealing cultural analysis (Żuk and Żuk 2022), or as a cosmopolitan moment (Webber 2005).

Indonesia declared its Independence Day on August 17th, 1945 by its founding father, Soekarno and Muhammad Hatta. Since then, Indonesia’s independence has been celebrated dynamically, following the social, political, and economic developments that surround it (Adams 1997; Agus et al. 2020; Hatley 1982; Tanasaldy and Palmer 2019). Television, newspapers, and radio were the mass media that made news of the celebration of Indonesian independence at that time (Hatley 2012; Hellman 2007; Wild 2007). Anderson (1983, 2006), a political scientist and historian, noticed that newspapers had become print capitalism, which was employed by elite groups to instill a sense of nationalism in society. Nowadays, in the era of digitalization, nationalism changed its shape (Budnitskiy 2018; Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez 2021), in which social media is considered to be one of the contributing factors (Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez 2021). Despite the era of globalization being considered to threaten the existence of this ideology, globalization through social media has spread the spirit of nationalism from one country to another as well.

With 68.9 percent of social media users at the beginning of 2022 (Kemp 2022), Indonesian nationalism in the current digital era continues to experience dynamics through social media. Social media is closely related to relationships and activities of daily life. Social media increasingly makes bonds of offline contexts constantly online, and, due to the ambient nature of this technology, awareness of the opinions, interests, and activities of social ties has spread (Hall 2016; Pulido et al. 2018). It is very important to know the fashion of the nationalism movement that occurs on social media. For this purpose, analytical data from appropriate social media platforms are required.

The most popular social media used for discussing a topic is Twitter. This platform has a wide audience reach (Lipschultz et al. 2022) and can specifically grasp those who are interested in a particular topic through hashtags (#) (Rauschnabel et al. 2019). This platform allows direct two-way communication so that feedback on a topic can be attained. In addition, Twitter accounts are free so they do not restrict users from joining conversations related to certain topics (Morgan-Lopez et al. 2017). Because of its characteristics that may provide current information, the social media platform Twitter was chosen (Hasan et al. 2018; Stromer-Galley 2019). Twitter is conveniently accessible and is capable of connecting users through quick and frequent comments and posts as well. Users can employ likes, retweets, and views to maximize their publicity (Awan 2017).

Twitter, particularly, has been developed to support interactive multitasking. The multimedia information that is included in tweets is referred to as the interactive component (including hyperlinks, photographs, and videos). These tweets are not inherently consumed passively by the recipients. Instead, people may actively engage with this information or they can blur the lines and start creating their content if they leave comments on the original content or reply to the original tweeter (Murthy 2013; Steinert-Threlkeld 2018; Tong and Zuo 2021).

Numerous research on the use of Twitter as a communication channel has been used in the Indonesian context (Santoso 2021; Sari et al. 2021), but significant research related to the use of Twitter on Independence Day, particularly in Indonesia, has not been conducted. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the delivery structure of nationalism messages on Twitter in the context of Indonesian netizens. The comprehensive picture of how Twitter is used will extend to the analysis of this research.

2 Basic graph theory

Fuhse (2022, 2009) stated that humans live in a connected environment through dyadic relationships, symbols, schemes, scripts, and communication which creates social networks, which basically consist of two structures: vertex (associated with node) and edge (referred to as tie or connection) (Yang et al. 2020). Thus, this research focuses on two-term on basic graph theories, namely vertices and edges.

Investigating social network analysis, in which vertex is a social entity and edge is a relation embedded in them, will guide us in understanding the existence of virtual communities (Jan 2019). The dynamics of social relations (Bidart et al. 2020), social movements (Diani 2014), and cultural networks (DiMaggio 2014) are several studies that show the importance of studying social entities and their relations within the framework of social network analysis.

Vertices, the first structure of the network, are also known as vertex, nodes, items, agents, actors, or entities. It serves as many things: people, social structures (including work groups, organizations, institutions, teams, or even countries), keyword tags, videos, web pages, or represents physical events, locations, or events as well. Vertices often correspond to posts or authors on blogs and friends on social networking sites (Hansen et al. 2011a, b). These vertices data have attributes that describe each node. Attribute data, however, can generally describe a user’s demographic characteristics (such as gender, race, and age), a system used by users (such as messages posted, number of logins, and edits made), or other characteristics such as location or income (Hansen et al., 2011a, b).

The second structure of the network is the edges. Edges are associated with links, connections, ties, and relationships. It connects two vertices, which represent different types of relationships like proximity, kinship, collaboration, trade partnership, friendship, literature citation, investment, hyperlink, transaction, or any shared attribute. In short, an edge is any form of relationship or connection between two entities (Hansen et al. 2020a).

Moreover, edge analysis can be classified into two types: directed and undirected. A directed edge (also known as an asymmetrical edge) has a clear origin and destination, which is represented on the graph as a line with arrows pointing from the source point to the receiving point and can be reciprocated or not. Undirected edges (also known as symmetric or reciprocal edges), on the other hand, exist only between two people or things. There is no clear origin or destination in this reciprocal relationship. A line connecting two vertices without arrows represents an undirected edge in a graph (Hansen et al. 2020b).

As the use of digital media has increased and connected, Wellman (Wellman 2001) argued that networks cannot be studied in isolation because they can connect people, organizations, and knowledge (Castillo-De Mesa and Gómez-Jacinto 2020; Clark et al. 2017; Hendrickson et al. 2011; White et al. 2022). Visualized networks could help us understand the social world that generates benefits by providing many insights, which would not be possible if we used other approaches (Borgatti et al. 2018; Hansen et al. 2011a, b; Iglesias and Moreno 2020). According to Smith et al. (2009), previously unknown detailed data on social processes can now be understood through network visualization. Social researchers will also be supported when network visualization can be used to explore areas that have not previously been studied in their studies (D. L. Hansen et al. 2020a; Moody and Light 2020).

Researchers, professionals, and governments employ network visualization for a variety of purposes. Network visualization can be used to identify influencers (Sanawi et al. 2017) and describe a network of media agendas and explain the narratives that form on Twitter (Guo et al. 2017). In a crisis, it can be important communication to facilitate awareness and assist the decision-making process (Drosio and Stanek 2016; Karakosta et al. 2021; Onorati and Díaz 2015). Additionally, network visualization can be used to map relationships based on the user’s profession, topics discussed, and their relationship to the mass media (Abdelsadek et al. 2018; Ausserhofer and Maireder 2013; Williamson and Ruming 2016).

The effectiveness of risk communication on social media can be mapped with network visualization so that it is feasible for public health officials and agencies in planning, monitoring, or evaluating public discussions on Twitter (Pascual-Ferrá et al. 2022). Furthermore, it could describe the domain of news media and are a valuable resource for newsrooms seeking to gain insight into news events emerging from a stream of social media posts as well (Ahmed and Lugovic 2019).

3 Network analysis metrics

Social network measurement was focused on the number of simple connections. The measurement is more sophisticated over time as it develops and incorporates various variables such as network density, centrality, vertex and edge count, and bridge level. These metrics measurements integrate the complex network variables. The first mentioned metrics evaluate the characteristics of the entire network (network-level), while the rest evaluate the behavior of the individual node (vertex-level).

The density of the network captures the connectivity between the nodes by calculating the percentage of observed connections from the maximum possible if one node is connected to others. The centrality is the measure of the importance level of a node in the network based on some objective criteria in which some central nodes are located at the edge or periphery while others are in the middle of the network. It can be calculated in many ways, such as degree centrality, closeness centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality. In this work, the centrality calculation is restricted using degree and betweenness. The vertex count is the number of nodes in the network while the edge count is the number of connections between the nodes. However, the fifth metric, a bridge, occurs when the third node bridges the connection (“friend of a friend”). It is acting as an intermediary or a connector. When the node is missing, a gap or structural hole is formed in the network. Thus, the “bridge” presence is important to fill in this hole (Golbeck 2015; Hansen et al. 2020b).

Degree centrality describes the social connections (edges) quantity owned by a node in the network. This parameter quantifies the significance and effect of the individual user in the established network environment. Its value is equal to the number of social connections owned by a user. If a node has x number of connections, thus its degree of centrality is also x. For example, a node with an 8-degree centrality value shows eight connections it has. The more central a node, thus its degree of centrality value is higher, and vice versa. Zero-degree centrality of a node indicates its independency behavior. As the first vertex-level analysis, degree centrality can be divided into two terms, i.e., in-degree and out-degree centrality. The in-degree centrality counts the connection number directed to the node (pointed-in), while the out-degree counts the connection number directed from the node (pointed-out) as illustrated in Fig. 1.

3.1 Conceptualizing nationalism

Discussions on nationalism have been continuing for a long time, even though they were not initially conducted in a systematic procedure. Before the second half of the twentieth century, articles on nationalism began to be published in political science journals, which were usually case studies, written by historians, sociologists, or psychologists (Mylonas and Tudor, 2021). Later, over 1983, three significant studies on nationalism were released simultaneously. Benedict Anderson published Imagined Communities (Anderson 1983), The Invention of Tradition by Hobsbawm and Ranger (1983), and Nations and Nationalism by Ernest Gellner (1983, 2009). These scholars viewed the nation and nationalism as contemporary phenomena evolved of urbanization, industrialization, print capitalism, and anti-colonial struggle (Mylonas and Tudor 2021).

Ernest Gellner (2006), a leading scholar on nationalism, describes nationalism simply as mainly a political theory that argues that the political and national units should be coherent. It is also consistent with both natural and constructed methods of national identity formation because it defines nationalism along with its impact rather than its cause. Nonetheless, Gellner (2006) principal focus in Nations and Nationalism is on the causative relationship and connective development between industrialization and nationalism. Gellner puts nationalism as based on power, education, and shared culture, and as such. It is dynamic like its constituent elements and not a “permanent aspect of the human condition” (Hajjaj 2020). Anderson (1983) would subsequently identify the production and diffusion of language, particularly written language, as a precondition for a nationalistic sensibility, in many aspects adding to Gellner's concept. While Gellner asserts that cultural homogeneity is a necessity for industrial society and hence the production of nationalism, Anderson (1983) emphasizes the organic emergence of nationalism through the print media. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, on the other hand, introduce the phrase “invented tradition” as how many long-held traditions have been reinvented in the recent past. Additionally, Hobsbawm goes on to characterize manufactured traditions as a reaction to new conditions that attempt to portray at least some aspects of social life throughout the modern world as permanent and invariant. Hobsbawm then distinguishes between “tradition,” “custom,” and “convention.” Contrary to tradition, the custom is not regarded to be immutable and must remain adaptable. It is a well-established procedure that can be simply modified if required. The convention is merely routine in the absence of any ceremonial or symbolic function. Both convention and custom are practices that make life easier, but none has an intellectual foundation like tradition (Singenberger 2021).

Traditionally, nationalism has been divided into ethnic and civic variants. As Kohn, a historian and politician scientist posited that civic nationalism is founded on citizenship and individuals’ capacity to join the nation. However, ethnic nationalism is rooted in the notion of shared ancestry and hence is less inclusive (Kohn 1944). While this idea was previously valuable, it yet assists, even though on a minor scale (Bieber 2018).

In advancement, in its development, Kohn’s distinction of nationalism has been criticized. Civic/ethnic distinction influences present-moment politics. First, the dichotomy presupposes that ethnic conflicts are indeed encountered in the East, encouraging us to dismiss the expansion of racial and ethnic tensions inside purported civic Western democracies. Western democracies profess to be more peaceful and inclusive than they are by flying the civic flag, developing a self-image that allows them to exonerate themselves, leaving them unable to cope with internal issues (Tamir 2019). Second, the civic/ethnic distinction promotes the notion that in civic countries, culture, religion, language, ethnicity, and race perform minor roles and may indeed be dismissed. This presumption compels us to reconsider the relationship between politics and identity. Members of minority groups pushed the majority to admit that identity influences not only who we are but also what we get during the initial stage of this debate. In light of the emergence of identity politics, identity concerns could not be ignored, resulting in the age of multiculturalism (Tamir 2019).

In addition, perceiving nationalism through Kohn’s perspectives can also be observed from the modes throughout which nationalism operates. Nationalism, as per Benedict Anderson, is a mode of representation. The nation refers to the imagined community made possible by the forces of representation liberated by printing press technology (Squibb 2016). Meanwhile, Ernest Gellner considers nationalism as a mode of reproduction in a different sense, arguing that it is required for industrial production (Squibb 2016).

Entering the digital age, nationalism nowadays interacts in complex ways with technological information and communication networks, frequently resulting in unexpected outcomes (Schneider 2022). Thus, scholars need to pay attention to the role information and communication technologies play in a discussion of nationalism. As Schneider argued, ‘digital nationalism’ is an emergent characteristic of communication networks and a result of technical affordances, economic incentives, and policy decisions (Schneider 2018). Furthermore, critical issues that emerge in studying digital nationalism are the investigation that requires conceptual and empirical work if we need a better understanding of how interactions between humans and technology produce and shape nationalism in advanced information societies. Therefore, the purpose of this research is to provide empirical work on these concerns.

3.2 Conceptualizing netizens

Performing research on nationalism in its digital era will investigate netizens as well. As MacKinnon argued, netizens are defined as those who digitally ‘inhabit’ and rely on digital platforms, networks, and services (MacKinnon 2012). They have the option of being passive ‘users,’ accepting their lot as given by governments and corporations which claim to know what is best for them. Alternatively, they can choose to express themselves as “netizens” and work actively to ensure that the Internet grows following their rights and interests (MacKinnon 2012). Extensively, there are three vectors of power in cyberspace: government, enterprises, and what can be called “the netizenry,” “digital civil society,” or “citizen commons.” The netizenry’s power must be enhanced to the point where it can successfully challenge the power of government and corporations (MacKinnon 2012).

The importance of the existence of netizens has occasionally received prominent recognition (Hauben 2019). Netizens’ demand for popular science (L. Wang and Zhong 2019), netizens’ participation to support the government in times of crisis (J. Guo et al., 2018), netizens’ digital activism in Zimbabwe (Nyoka and Tembo 2022), and netizens engagement patterns (Hasfi et al. 2021; Seman et al. 2019) are several studies that have been conducted to examine netizens’ influence in each of the nations researched.

3.3 Conceptualizing hashtag

Over the last ten years, the popularity of social networks has also been a success for the keyword. Since the introduction of the “hashtag” by Twitter and Instagram in 2007 and 2010, respectively, a method of categorizing remarks and documents that were previously exclusive to highly specialized professional groups has marked prevalent media use (Bernard 2019). Today, every Twitter feed and Instagram post contribute to the community indexing or “keywording” of the world, which can be performed as a creative act by every user of these social networks, unconstrained by predefined rules or hierarchically tiered access procedures.

Documents could only be linked to one another in the initial periods of the “World Wide Web,” as is widely recognized. In many aspects, the shift from “link” to “hashtag” as a defining networking notion represented a significant transition in the digital structuring of statements. First, it indicated that every Internet user could initiate links independently and without requiring any programming skills, paving the way for the Internet’s more even “social” and fostering a participatory era. Second, it signified that for the first time, a mechanism for establishing connections was supplied with its typographic element. The prefixed symbol “#”—referred to as a “hash” in British English or a “pound sign” in American English—converts words into networked keywords. Thus, the hashtag and the letters immediately following it have two purposes: They are both a component of visible tweets or Instagram posts, as well as a trigger for the invisible mechanism that connects them (Bernard 2019).

As Rocca argued, hashtags were a cultural product. Additionally, if we consider hashtags to be cultural products, altering their meaning throughout human action, we should ask ourselves what we can learn from them (Rocca 2020). When analyzing data retrieved from social media and indexed by hashtags, we must acknowledge the significance of the hashtag’s social construction and the meanings that exist underneath it. Whether we apply them for audience analysis (Fisher and Mehozay 2019; Gallagher et al. 2019; Maireder et al. 2015) or cataclysmic events (Lovari and Bowen 2020; Mirbabaie et al. 2021; Yan and Pedraza-Martinez 2019), we must consider that they are formed with a certain sense attribution, but that it alters as a result of contact, developing the various selves that hashtag represents.

4 Methods

As part of content analysis, a quantitative approach was used. Data were collected from Twitter using NodeXL Professional for Academics (NodeXL Pro). NodeXL was chosen because it offers a wide range of options for optimizing Twitter network analysis. As it runs on Microsoft Excel, many types of statistics can be used. Furthermore, NodeXL provides a friendly way to browse the Twitter network with the automated functions offered (Yu and Muñoz-Justicia 2020). The time selected was August 18th, 2021. This time was chosen because of the high level of discussion on Indonesia’s Independence Day. The data were taken one day after Indonesia’s Independence Day with the intention it can capture all conversations on Independence Day.

To collect data from Twitter related to Indonesia’s Independence Day, the #HUTRI76 keyword was used. This work on Twitter has focused on conversations coordinated by hashtags. The hashtag is a keyword or short abbreviation, beginning with the ‘#’ symbol and indicates a special discursive marker (Bruns and Stieglitz 2013; Small 2011). Moreover, we use hashtags because of their effective mechanism to capture all Twitter features (including tweets, replies, or retweets) (Bruns 2011).

On Indonesian Independence Day, #HUTRI76 emerged in Indonesia’s Twitter trending topics. We chose Independence Day because it is a symbol of nationalism (Paasi 2016), a form of an exhibition of nationalism (Agastia 2017), as well as a symbolic and ritualistic form of nationalism (Hyttinen and Näre 2017).

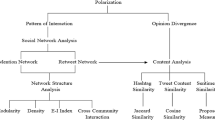

Afterward, the data were collected, and then, they were analyzed and visualized. The analysis was carried out in three parts. First, analysis of the network structure to find influential users by evaluating the value of several parameters, viz. in-degree, out-degree, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality. The second analysis was conducted to examine the message structure on the #HUTRI76 network by detecting the top twenty words and words pair on the #HUTRI76 network. The third analysis was conducted to figure out the media used by users in delivering the messages of Indonesia’s Independence Day. As these three analyses were executed, the delivery structure of nationalism messages through Twitter in the Indonesian context emerged.

5 Result and discussion

5.1 The network structure of influential users on #HUTRI76

Analysis was set up by admitting the metric of the #HUTRI76 network. The network metric formed among Indonesian digital citizens on the issue of Indonesia’s Independence Day is presented in Table 1. In this network, 14,686 accounts/users joined the conversation and built 20,163 connections with the possibility of forming a connection of only 0.0088%. Moreover, each account needs 6.85 of average path length to reach another account of the network to share information, which reveals the efficiency of information transfer in the network.

5.1.1 Incoming engagement users

The significance of users on the Twitter network can be determined based on the centrality of incoming and outgoing. In addition, engagements between users and their content on Twitter can be captured through in- and out-degree centrality metrics. Actual attention given to content as well as users’ actions taken to disseminate information is indicated through these things (D. L. Hansen et al. 2020c).

More attention to tweets among the community of users who participate in conversations dealing with a particular topic is gained by users with a high degree of centrality. Thus, centrality at the user level captures engagement in a community. High centrality scores exist for users who are considered the center of the conversation because other users have replied to, mentioned, or retweeted their posts. Thus, in-degree is an indication of the information flow initiated by the user. In addition, users can have high login rates on one topic network, but low login rates on another network. On the other hand, the out-degree centrality metric is measured by capturing the level of user-initiated engagement with community members.

Figure 2 shows the in-degree and out-degree distribution related to the issue of Indonesia’s Independence Day events on the #HUTRI76 Twitter network, while the percentage of three categories of the degree’s values is summarized in Table 2. As revealed in Fig. 2a and Table 2, the majority of users (73%) are independent users (unconnected to one another) as indicated by zero in-degree value. It shows the independency of this Twitter user (lack of influence from another user). As Jendoubi et al. (2018) point out, independent users are generally not swayed and are independent in their choices and decisions. Independent users can draw and drive another user’s point of view. Meanwhile, the minor population (0.7%) are the interesting users. Only the minor population gained more attention to their tweets among the community of users who participate in the conversation about Indonesia’s Independence Day by mentioning, replying to, or retweeting their posts. As shown in Table 2, a Twitter user is eligible to be independent when his perspective does not depend on other people’s ideas. Thus, the user’s behavior is independent of other user behaviors. Detection of independent users is crucial since some of them can become influencers. It is similar to Räbiger and Spiliopoulou (2015) study which underlines the importance of distinguishing influencers from non-influencers on Twitter. Those who are not influencers can be directly targeted because they can be persuaded. However, we propose that independent users can be considered as influencers although not all independent users are influencers. This finding conforms to the study of Bokunewicz and Shulman (2017) which finds that popularity is not the only indication of influence in a network, or refers to the study of Räbiger and Spiliopoulou (2015) which states that writing influential tweets is not a prerequisite for becoming an influential user.

5.1.2 Outcoming engagement users

As revealed in Fig. 2b and Table 2, the majority of users are active users (initiate the connection to other users and actively post tweets) as indicated by the nonzero out-degree value (Hansen et al. 2020b). The out-degree centrality value shows the user’s attention to the topic of Indonesia’s Independence Day by mentioning or replying to a tweet (Hansen et al. 2020a). Out-degree centrality, then, reflects the level of user-initiated engagement with community members within the #HUTRI76 network. Out-degree centrality graphs the outreach of a user to the community. Users who tweet a lot about a topic are represented with a high degree of centrality value. They intend to grasp the user’s attention by replying or mentioning them.

A high out-degree centrality of the #HUTRI76 network, which has a value of more than 30, was found to be 0.2%. The level of engagement a user initiates with members of the community, thus, is captured by this user. This indicates that they tweet a lot about a topic by mentioning or replying, aiming to reach users’ attention. These users generate a high level of engagement with other users for content about Indonesian Independence. The user has control over other users in terms of the dissemination of information on Indonesian Independence. This is similar to the study of Aleskerov which stated that important user has a significant role in various fields (Aleskerov et al. 2021). Moreover, 6% of the user population has zero value of out-degree which means most of the users in this Twitter network have an impact on other users. This is reinforced by Carolina, Guido, Renaud, and Fabio’s research which stated that users with the highest out-degree were identified as the most popular users, while users with the highest out-degree posts were the most “viral” (Becatti et al. 2019). It was revealed that challenges with high out-degree centrality can create many other challenges (Himelboim et al. 2017; Jami Pour et al. 2022).

Furthermore, we can identify that these users pay more attention to the actual information as well as the actions taken to spread information about Indonesia’s Independence Day. This character is unique and authentic to the character of Indonesian netizens. Indonesia has a high level of participation in Internet use. According to other research, the level of community participation appears in the form of participation in various voluntary activities (Irandoost et al. 2022; Niebuur et al. 2018). Predominantly, the research shows a positive relationship between social media use and participation (Boulianne 2015). On the other hand, Arwati and Latif’s article shows that Indonesian public participation in e-government implementation remains low, as a result of public knowledge of government data and information, which has not been adequately accounted for in terms of its assistance, especially to anti-corruption efforts. (Arwati and Latif 2019).

Most users have a low value of both degree centrality which lies in the ranges of 0–10, thus we only show the distribution in that interval. It shows that most users in the #HUTRI76 Twitter network have scattered users. In other words, various accounts that tweet mentioning other accounts (out-degree) in the #HUTRI76 network, as well as accounts mentioned by others (in-degree), are in the high category. However, several accounts (in which ID stands for account Identity) have in-degree and out-degree scores with a higher mean than other accounts in the network. These four accounts are ID 3176, ID 970, ID 224, and ID 261.

5.1.3 Cross-engagement users

To observe the significant users that impact outside, as well as receive much popularity (double-central user), the in-degree and out-degree of each user are paired and presented in Fig. 3. Only four users, i.e., ID 3176, ID 970, ID 224, and ID 261, fulfilled the criteria of the double-central user. They not only have control and power over others but also have popularity among the adjacent users in the #HUTRI76 network on Twitter.

ID 3176 mentions ID 3173 to respond to the tweet ‘Mensen temen lo yang layak juara 1 lomba menahan rindu disaat PPKM (Mention your friend who deserves 1st place in the contest to holding back during PPKM)’. User ID 3176 has an in-degree score of 37 and an out-degree value of 19. The user ID 3176 betweenness centrality value is 402748,972886. Surprisingly, ID 3176 appears on two parameters, i.e., cross-engagement metric and betweenness centrality metric. This makes ID 3176 act as an influential user as well as a bridge between users in the conversation of Indonesia’s Independence Day.

5.1.4 Bridges between users

The number of connections in a network is used to determine a vertex’s degree of centrality. Because they link users who would otherwise be unconnected or insufficiently linked, users (i.e., vertex) can also play a significant role in a network. On the other hand, betweenness centrality quantifies the extent to which a vertex serves as a connecting point in a network. The degree to which the user is located on the shortest path between another user in the network is measured by betweenness centrality. A user’s betweenness centrality increases as more people rely on them to connect them with others.

Thus, actors positioned in structural gaps in a network profit strategically by exercising power, getting access to innovative information, and brokering resources. Because of their structural position and associated benefits, actors who fill structural gaps are considered engaging relationship partners. These actors are referred to as brokers or bridges because they fill a brokerage position. These actors connect otherwise less connected actors through non-redundant, frequently weak ties. Actors who bridge social gaps or act as social mediators place high importance on both betweenness and in-degree.

Figure 4 shows the top ten of users with the highest betweenness centrality value on the #HUTRI76 network. The user can act as a bridge in the flow of information if he/she has a high betweenness centrality value. All information is directed to be able to go through the ten users. Users can also act to reduce the flow of information and act as gatekeepers as well. Thus, the ten users in the #HUTRI76 network play an important role in the flow of information in the entire network.

The previously mentioned ten users with the highest score of betweenness centrality consist of various community groups. The first group is regional leaders (ID 2582 and ID 1148), football club (ID 13), content creator (ID 29), study center (ID 11), ID 20, ID 11,186, freelance MV animator (ID 1603), K-Pop fans (ID 1503), and Vtuber agency (ID 6740). The diversity of user groups based on betweenness centrality reveals that micro-blogs, particularly Twitter, can create the nature of online participation. It means the audience is not only passively reading content on social media. Audiences even contribute by creating content (Faizal Kasmani et al. 2014), as well as it has the potential for the development of democracy (Schreiner 2018).

In social network analysis, betweenness centrality has other implications. From a macroscopic perspective, the bridging position indicated by high betweenness centrality reflects strength. This is because it allows them to exercise control over, for example, deciding whether or not to share information with users on a network (Burt 2009). In online social networks, high betweenness centrality corresponds to relationships between the closest friends when observed from the microscopic perspective of ego networks (i.e., in light of first-degree connections). This is due to the connection reflecting the social capital invested in the relationship when distant social circles (such as family and university) are linked, which frequently happens as a result of ego recognition (Stolz and Schlereth 2021).

Based on Fig. 4, it was found that 81% of the accounts had a zero-centrality value. From a macroscopic perspective, it explains the weak strength of the user interface in the network. On the one hand, users tend to decide not to share information with other users, while on the other hand, users also tend to have no control over other users in the #HUTRI76 network. In contrast, 19% of accounts have a nonzero betweenness centrality value. From a macroscopic perspective, this group of users has control over the information they have. They tend to provide information to other users on the network. Even from a microscopic perspective, this group of users has strong interpersonal bonds with other users.

Thus, on the #HUTRI76 network, the emergence of various circles of society on Twitter informs several things. First, all community groups show expressions to celebrate Indonesian Independence Day. Both groups of people admitted their national identity by posting tweets related to Indonesia’s Independence Day. The third is the excitement of Twitter users on Indonesia’s Independence Day. Regional heads, politicians, football clubs, content creators, etc., participated in this event.

To expand the analysis of users who have influence, the values of betweenness centrality and eigenvector centrality are paired. The eigenvector represents the magnitude of the influence or importance of nodes in a network. Figure 5 displays four users with high eigenvector values and high betweenness centrality values. They are ID 9267, ID 10,851, ID 1110, and ID 3176. These four accounts have a strong influence as a bridge in disseminating information on the network, as well as having a strong influence on other users in the #HUTRI76 network.

5.2 The message structure on the #HUTRI76

Figure 6 denotes the 20 most used words and word pairs on the #HUTRI76 network. Figure 6a reveals the word ‘#hutri76’ ranks first with 19,657 uses of the word, while the word ‘selamat’ is the twentieth most frequently used word on the #HUTRI76 network with 1,826 uses. Among the top twenty words, ‘hutri76,’ ‘Indonesia,’’17-an,’ ‘dirgahayu,’ ‘kemerdekaan,’ ‘republik,’ and ‘kita,’ ‘merdeka,’ and ‘selamat’ were related to discussions of nationalism. The word ‘Indonesia’ refers to the name of the country, the word ‘independence’ refers to freedom from colonialism, and the word ‘republik’ refers to the form of the Indonesian state, which is in line with Blondel (2005) and Pettit (2002) intention that republican government prioritizes the voice of the people.

‘#hutri76’ is an abbreviation of ‘hari ulang tahun Republik Indonesia’ ke-76’ (the 76th anniversary of the Republic of Indonesia-in English), which refers to the public’s memory of Indonesia’s Independence Day from the Dutch which reached 76 years of age. As Malinova (2021) stated, memory is essential for each identity. Hence, we need to review memory politics, which refers to the public activities of several social individuals and organizations. It aimed at promoting certain interpretations of a collective history and establishing an appropriate sociocultural infrastructure of remembering, school curriculum, and, in some cases, special laws (Malinova 2021). We propose that regarding Kohn’s perspective, collective interpretations of the past and shared representations thus far emerge in Indonesia within the framework of ‘civic nationalism’ (Kohn 1944).

The word ‘kita’ (us-in English) refers to the bond of Indonesian national identity. As this term was used by Smith (2010) which refers to the deep bond within a country that serves to strengthen the sense of belonging together, although, on the other hand, the word ‘kita’ has implications for ethnocentrism. Similarly, Knott argued that nationalism is related to the sense of belonging. Furthermore, the nation is a particularly powerful kind of belonging that produces a sense of oneness to those regarded as members of the nation and territories, as well as a feeling of distinction to those considered as outsiders, i.e., non-members. Insiders regard belonging to the nation as a personal, deep sense of belonging which creates an emotional (or even ontological) commitment as a continuous endeavor of belonging to people and places (Knott 2017). Meanwhile, in Kohn’s idea, this sense of belonging is a form of ethnic nationalism (Kohn 1944).

The use of the local Indonesian word ‘dirgahayu’ is the most frequently used word as well. ‘dirgahayu’ in Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia means long life. This word is usually addressed to a country or organization that is celebrating its Independence Day. In the Indonesian context, the word ‘dirgahayu’ is not only implemented on Independence Day but is often used on the anniversary of the Indonesian army as well. Thus, this word is closely related to the language used by the Indonesian government at the moment of the anniversary of the state or state organizations. This choice of words also represents nationalist language ideologies (Vessey 2021).

The use of the English words ‘happy’ and ‘independence’ indicates the discourse on Indonesia’s Independence Day aimed to be known at a global level. As a community uses language to communicate, they employ language that allows them to interact with others. Indeed, English is the language of the global community (Crystal 2003; Northrup 2013; Salomone 2022).

Figure 6b is a graph pointing to the top 20 most frequently used word pairs on the #HUTRI76 network. The highest number of word pairs is ‘#hutri76’ with the word ‘#17an’ which is used 3436 times, while the number of word pairs in the twentieth most frequently used is the word ‘agustus’ with the word ‘2021’ with total usage of 749 times. Among these word pairs, there are two pairs of words used by the Government of Indonesia which are used as slogans on Indonesia’s Independence Day. The two pairs of slogans are the word ‘Indonesia’ with the word ‘tangguh’ and ‘Indonesia’ with the word ‘tumbuh.’ ‘Indonesia tangguh, Indonesia tumbuh’ is a phrase on Indonesia’s Independence Day in 2021. This phrase was made by the Government of Indonesia to commemorate Indonesia’s Independence Day amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Based on the findings of the use of these words and word pairs, we argue that the discourse of nationalism on the #HUTRI76 network is dominated by the use of discourse from the Government of Indonesia. Thus, the process of reproduction discourse occurs in this network. The state, in this case, yet dominates the discourse of nationalism on Twitter.

5.3 The media structure on #HUTRI76: twitter as a hub

As stated by Murthy (2018), who first structured the idea of the study on Twitter, the interactive part of other platforms may turn out on Twitter. On the #HUTRI76 network, various hyperlinks, videos, and even social media on Facebook are embedded in tweets. The top ten hyperlinks on the #HUTRI76 network emerged. The first most shared medium was hyperlinked, of which six of them are hyperlinks from YouTube. Meanwhile, the other medium interpolated in tweets is one Facebook hyperlink, two Twitter hyperlinks, and one Yahoo online news hyperlink. The variety of mediums inserted in these tweets indicates a platform-sensitive framework (Burgess et al. 2018). Platform-sensitive emphasizes the specificity of the platform as a socio-technological environment that draws different users together and regulates the relationship between users of different platforms to provide things for different types of users. The specificity of this platform can also provide an overview of the users who are connected through various possible actions. Media richness then could be emerged on discussions related to Indonesia’s Independence Day on the #HUTRI76 network over Twitter as a hub.

The formed modes in the nationalism message delivery related to Indonesia’s Independence Day event in the #HUTRI76 Twitter network are summarized in Fig. 7. Interrelationships between media structure, message structure, and user structure are found in this model. As has been shown, the delivery of messages of nationalism, with local and global narratives, related to #HUTRI76 which is formed in the Twitter network, is built through interactions between users. In these interactions, special word forms are used to represent certain messages involving various types of online media platforms that are linked to the Twitter network.

6 Conclusion

The delivery structure of nationalism message on Twitter in the context of Indonesian netizens has been investigated by employing social network analysis. Through the #HUTRI76 Twitter network, an overview of influential people, topics discussed, and content embedded in tweets on Indonesia’s Independence Day emerged. The presence of significant users was detected in the network as they have an impact on other users on the network, as well as receive much popularity (double-central users). Moreover, users which act as a bridge on the network arise and reveal the diversity of user groups in the #HUTRI76 network. This bridge has an important role to connect users on the network in discussing Independence Day. Without their existence, no conversation developed.

Furthermore, the developing conversations were referring to local and global discourse. At the local level, specific terms of words reflecting Indonesia’s national identity such as ‘kemerdekaan,’ ‘kita,’ and ‘dirgahayu’ were utilized to discuss Independence Day. Even though these terms serve to strengthen the sense of national belonging, these words have implications for the formation of ethnocentrism as well. The words in English, i.e., ‘happy’ and ‘independence’ are intended to make the discourse of Indonesian Independence known globally. At this moment, especially in the discussion of #hutri76, the terms are used in forming civic nationalism—referring to individuals’ capacity to join the conversation on Twitter, as well as ethnic nationalism—attributing to the notion of shared ancestry and inclusiveness. These two forms of nationalism are possible because currently, these two concepts cannot be separated from one another.

Meanwhile, there are a variety of mediums embedded in tweets discussing Indonesia’s Independence Day. The top ten hyperlinks are found and revealed on the network. Thus, Twitter could act as a hub for other social media to do cross-posting content. Due to its flexibility and openness to links and updates from other networks, Twitter is believed to be a cross-posting platform echoing the discourse on Indonesian Independence Day through the #HUTRI76 Twitter network.

References

Abdelsadek Y, Chelghoum K, Herrmann F, Kacem I, Otjacques B (2018) Community extraction and visualization in social networks applied to Twitter. Inf Sci 424:204–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INS.2017.09.022

Adams KM (1997) Nationalizing the local and localizing the nation ceremonials, monumental displays and national memory-making in upland Sulawesi. Indones Mus Anthropol 21(1):113–130. https://doi.org/10.1525/MUA.1997.21.1.113

Agastia ID (2017) Celebrating independence, recounting common struggle. The Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2017/08/16/celebrating-independence-recounting-common-struggle.html

Agus C, Cahyanti PAB, Widodo B, Yulia Y, Rochmiyati S (2020) Cultural-based education of Tamansiswa as a locomotive of Indonesian education system. World Sustain Ser. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15604-6_29/COVER/

Ahmed W, Lugovic S (2019) Social media analytics: analysis and visualisation of news diffusion using NodeXL. Online Inf Rev 43(1):149–160. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-03-2018-0093/FULL/XML

Akuupa MU, Kornes G (2015) From ‘One Namibia, one Nation’ towards ‘unity in diversity’? Shifting representations of culture and nationhood in Namibian Independence Day celebrations, 1990–2010. Anthropol S Afr 36(1–2):34–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/23323256.2013.11500041

Aleskerov FT (Faud T ogly), Shvydun S, Mescheryakova N (2021) New centrality measures in networks : how to take into account the parameters of the nodes and group influence of nodes to nodes. Chapman and Hall/CRC. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003203421

Anderson BRO (1983) Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso

Anderson BRO (2006) Imagined communities : reflection on the origin and spread of nationalism (revised ed). Verso

Arwati D, Latif DV (2019) Factors inhibiting public participation in corruption prevention through E-government application in Indonesia. Glob Bus Manag Res Int J 11(1):81–86

Ausserhofer J, Maireder A (2013) National politics on twitter. Inf Commun Soc 16(3):291–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.756050

Awan I (2017) Cyber-extremism: isis and the power of social media. Society 54(2):138–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12115-017-0114-0/TABLES/5

Becatti C, Caldarelli G, Lambiotte R, Saracco F (2019) Extracting significant signal of news consumption from social networks: the case of Twitter in Italian political elections. Palgrave Commun. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0300-3

Bernard A (2019) Theory of the hashtag. Polity Press

Bidart C, Degenne A, Grossetti M (2020) Living in networks: the dynamics of social relations. Cambridge University Press

Bieber F (2018) Is nationalism on the rise? Assess Glob Trends Ethnopolitics 17(5):519–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2018.1532633

Blondel J (2005) The Presidential Republic. Palgrave Macmillan

Bokunewicz JF, Shulman J (2017) Influencer identification in Twitter networks of destination marketing organizations. J Hosp Tour Technol 8(2):205–219. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-09-2016-0057/FULL/PDF

Borgatti SP, Evertte MG, Johnson JC (2018) Analyzing social networks. SAGE Publications

Boulianne S (2015) Social media use and participation: a meta-analysis of current research. Inf Commun Soc 18(5):524–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1008542

Breuilly J, Halikiopoulou D (2022) N&N Themed section: reflections on nationalism and the Russian invasion of Ukraine: Introduction. Nations Natl. https://doi.org/10.1111/NANA.12874

Brown H (2017) Post-Brexit Britain: thinking about ‘English Nationalism’ as a factor in the EU referendum. Int Polit Rev 5:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41312-017-0023-7

Bruns A (2011) How long is a tweet? Mapping dynamic conversation networks on twitter using Gawk and Gephi. Inf Commun Soc 15(9):1323–1351. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.635214

Bruns A, Stieglitz S (2013) Towards more systematic Twitter analysis: metrics for tweeting activities. Int J Soc Res Methodol 16(2):91–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.756095

Budnitskiy S (2018) Digital nationalisms: identity, strategic communication, and global internet governance [Carleton University]. https://curve.carleton.ca/system/files/etd/c88cf12b-8b77-4a50-9b91-ea458c26f227/etd_pdf/404c7c902d139b006831792437ce9b1f/budnitskiy-digitalnationalismsidentitystrategiccommunication.pdf

Burgess J, Marwick AE, Poell T (Eds) (2018). The SAGE handbook of social media. Sage Publications Ltd

Burt RS (2009) The social structure of competition. Harvard University Press

Cannadine D (2008) Introduction: Independence Day ceremonials in historical perspective 1. Round Table Commonw J Int Aff 97(398):649–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358530802327829

Castillo-De Mesa J, Gómez-Jacinto L (2020) Connectedness, engagement, and learning through social work communities on LinkedIn. Psychosoc Interv 29(2):103–112. https://doi.org/10.5093/PI2020A4

Clark JL, Algoe SB, Green MC (2017) Social network sites and well-being: the role of social connection. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 27(1):32–37

Crystal D (2003) English as a global language. Cambridge University Press

Diani M (2014) Social movements and collective action. In: The SAGE handbook of social network analysis, SAGE Publications Lt

DiMaggio P (2014) Cultural networks. In: The SAGE handbook of social network analysis, pp 286–300. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446294413.N20

Drosio S, Stanek S (2016) The Big Data concept as a contributor of added value to crisis decision support systems. J Decis Syst 25(s1):228–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2016.1187404

Duffy M (2022) Shinzo abe’s murder and Japan’s History of political assassination. E-international relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2022/07/08/opinion-shinzo-abes-murder-and-japans-history-of-political-assassination/

Faizal Kasmani M, Sabran R, Ramle N (2014) Can Twitter be an effective platform for political discourse in Malaysia? A study of #PRU13. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 155:348–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.304

Fisher E, Mehozay Y (2019) How algorithms see their audience: media epistemes and the changing conception of the individual. Media Cult Soc 41(8):1176–1191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719831598

Fuhse JA (2009) The meaning structure of social networks. Sociol Theory 27(1):51–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-9558.2009.00338.X

Fuhse J (2022) Social networks of meaning and communication. Oxford University Press

Gallagher JR, Chen Y, Wagner K, Wang X, Zeng J, Kong AL (2019) Peering into the internet abyss: using Big Data audience analysis to understand online comments. Tech Commun Q 29(2):155–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2019.1634766

Gellner E (1983) Nations and nationalism. Cornell University Press

Gellner E (2006) Nations and nationalism. Blackwell

Gellner E (2009) Nations and nationalism (second edi). Cornell University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Nations-Nationalism-New-Perspectives-Past/dp/0801475007/ref=sr_1_1?crid=BK412RBEX9LG&dchild=1&keywords=ernest+gellner&qid=1614871404&s=books&sprefix=ernest+gellner%2Cstripbooks-intl-ship%2C535&sr=1-1

Giroux HA (2017) White nationalism, armed culture and state violence in the age of Donald Trump. Philos Soc Crit 43(9):887–910. https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453717702800

Golbeck J (2015) Analyzing networks. In: Introduction to social media investigation, pp 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801656-5.00021-4

Guo L, Mays K, Wang J (2017) Whose story wins on Twitter? Journal Stud 20(4):563–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1399813

Guo J, Zhang C, Wu Y, Li H, Liu Y (2018) Examining the determinants and outcomes of netizens’ participation behaviors on government social media profiles. Aslib J Inf Manag 70(4):306–325. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-07-2017-0157

Gusterson H (2017) From Brexit to Trump: anthropology and the rise of nationalist populism. Am Ethnol 44(2):209–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12469

Hajjaj B (2020) Nationalism and national identity formation in Bangladesh: a colonial legacy behind the clash of language and religion. Asian J Comp Polit 7(3):435–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057891120938145

Hall JA (2016) When is social media use social interaction? Defining mediated social interaction. New Media Soc 20(1):162–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816660782

Hansen DL, Shneiderman B, Smith MA, Himelboim I (2020a) Analyzing social media networks with NODEXL insights from a connected world. Morgan Kaufmann

Hansen DL, Shneiderman B, Smith MA, Himelboim I (2020b). Social network analysis: measuring, mapping, and modeling collections of connections. In: Analyzing social media networks with NodeXL: insights from a connected world. Morgan Kaufmann. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817756-3.00003-0

Hansen DL, Shneiderman B, Smith MA (2011a) Social network analysis: measuring, mapping, and modeling collections of connections. In: Analyzing social media networks with NodeXL, pp 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-382229-1.00003-5

Hansen D, Shneiderman B, Smith MA (2011b) Analyzing social media networks with NodeXL: insights from a connected world. Elsevier Inc

Hansen DL, Shneiderman B, Smith MA, Himelboim I (2020c) Twitter: information flows, influencers, and organic communities. In: Analyzing social media networks with NodeXL: insights from a connected world, pp 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817756-3.00011-X

Hasan M, Orgun MA, Schwitter R (2018) A survey on real-time event detection from the Twitter data stream. J Inf Sci 44(4):443–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551517698564/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0165551517698564-FIG1.JPEG

Hasfi N, Fisher MR, Sahide MAK (2021) Overlooking the victims: Civic engagement on Twitter during Indonesia’s 2019 fire and haze disaster. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 60:102271. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJDRR.2021.102271

Hatley B (1982) National ritual, neighborhood performance: celebrating Tujuhbelasan. Indonesia 34:55. https://doi.org/10.2307/3350948

Hatley B (2012) Performing identity and community in Indonesia in modern times. ACCESS Crit Perspec Commun Cult Policy Stud 31(2):27–38

Hauben M (2019) Researching the “net” a talk on the evolution of usenet news and the significance of the global computer network. Amat Comput 32(2):1–30

Hellman J (2007) The use of ‘cultures’ in official representations of Indonesia: the fiftieth anniversary of independence. Indones Malay World 26(74):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639819808729907

Hendrickson B, Rosen D, Aune RK (2011) An analysis of friendship networks, social connectedness, homesickness, and satisfaction levels of international students. Int J Intercult Relat 35(3):281–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJINTREL.2010.08.001

Himelboim I, Smith MA, Rainie L, Shneiderman B, Espina C (2017) Classifying Twitter topic-networks using social network analysis. Soc Media Soc. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117691545

Hobsbawm E, Ranger T (eds) (1983) The invention of tradition. Cambridge University Press

Hyttinen A, Näre L (2017) Symbolic and ritual enactments of nationalism: a visual study of Jobbik’s gatherings during Hungarian national day commemorations. Vis Stud 32(3):236–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2017.1358104

Iglesias CA, Moreno A (2020) Sentiment analysis for social media. MDPI AG

Irandoost SF, Sedighi S, Hoseini AS, Ahmadi A, Safari H, Ebadi Fard Azar F, Yoosefi Lebni J (2022) Activities and challenges of volunteers in confrontation with COVID-19: a qualitative study in Iran. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 82:103314. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJDRR.2022.103314

Jami Pour M, Hosseinzadeh M, Mansouri NS (2022) Challenges of customer experience management in social commerce: an application of social network analysis. Internet Res 32(1):241–272. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-01-2021-0076/FULL/PDF

Jan SK (2019) Investigating virtual communities of practice with social network analysis: guidelines from a systematic review of research. Int J Web Based Commun 15(1):25–43. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWBC.2019.098697

Jendoubi S, Chebbah M, Martin A, Evidential AM (2018) Independence maximization on Twitter network. In: International conference on belief functions. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01879620

Karakosta C, Mylona Z, Karásek J, Papapostolou A, Geiseler E (2021) Tackling covid-19 crisis through energy efficiency investments: decision support tools for economic recovery. Energy Strat Rev 38:100764. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ESR.2021.100764

Kemp S (2022) Digital 2022: Indonesia. Datareportal. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-indonesia

Knott E (2017) Nationalism and belonging: introduction. Nations Natl 23(2):220–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12297

Knott E (2022) Existential nationalism: Russia’s war against Ukraine. Nations Natl. https://doi.org/10.1111/NANA.12878

Kohn H (1944) The idea of nationalism. Macmillan

Kook R (2006) Changing representations of national identity and political legitimacy: Independence Day celebrations in Israel, 1952–1998. National Identities 7(2):151–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/14608940500144096

Kuzio T (2022) Imperial nationalism as the driver behind Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Nations Natl. https://doi.org/10.1111/NANA.12875

Lipschultz JH, Freberg KJ, Luttrell R (2022) The Emerald handbook of computer-mediated communication and social media. Emerald Publishing Limited

Lovari A, Bowen SA (2020) Social media in disaster communication: a case study of strategies, barriers, and ethical implications. J Public Aff 20(1):e1967. https://doi.org/10.1002/PA.1967

MacKinnon R (2012) The netizen. Development 55:201–204. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2012.5

Madu L (2017) Indonesia’s foreign policy under president Jokowi: more domestic and nationalist orientations. Int J Sci Res Sci Technol 2(3):189–197

Magcamit MI (2019) The fault in Japan’s stars: Shinzo Abe, North Korea, and the quest for a new Japanese constitution. Int Polit 57(4):606–633. https://doi.org/10.1057/S41311-019-00186-8

Maireder A, Weeks BE, Gil de Zúñiga H, Schlögl S (2015) Big Data and political social networks: introducing audience diversity and communication connector bridging measures in social network theory. Soc Sci Comput Rev 35(1):126–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439315617262

Malinova O (2021) Politics of memory and nationalism. Natl Pap 49(6):997–1007. https://doi.org/10.1017/NPS.2020.87

Mcewen N (2022) Irreconcilable sovereignties? Brexit and Scottish self-government. Territ Polit Gov 10(5):733–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2022.2044898

Merriman P (2020) National movements. Environ Plan C Polit Space 38(4):585–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420912445C

Mihelj S, Jiménez-Martínez C (2021) Digital nationalism: understanding the role of digital media in the rise of ‘new’ nationalism. Nations Natl 27(2):331–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/NANA.12685

Mirbabaie M, Ehnis C, Stieglitz S, Bunker D, Rose T (2021) Digital nudging in social media disaster communication. Inf Syst Front 23(5):1097–1113. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10796-020-10062-Z/TABLES/7

Moody J, Light R (2020) The oxford handbook of social networks. Oxford University Press

Morgan-Lopez AA, Kim AE, Chew RF, Ruddle P (2017) Predicting age groups of Twitter users based on language and metadata features. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183537

Murthy D (2018) Twitter: social communication in the Twitter age. Polity Press

Murthy D (2013) Twitter: social communication in the Twitter age. Polity Press

Mylonas H, Tudor M (2021) Nationalism: what we know and what we still need to know. Annu Rev Polit Sci 24:109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719

Niebuur J, Van Lente L, Liefbroer AC, Steverink N, Smidt N (2018) Determinants of participation in voluntary work: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. BMC Public Health 18(1):1–30. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-018-6077-2/TABLES/9

Northrup D (2013) How english became the global language. In: How english became the global language, pp 1–205. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137303073

Nyoka P, Tembo M (2022) Dimensions of democracy and digital political activism on Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume Twitter accounts towards the July 31st demonstrations in Zimbabwe. Cogent Soc Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.2024350

Nyyssönen H (2009) The politics of calendar: Independence Day in the Republic of Finland. In: National Days, pp 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230251175_10

Onorati T, Díaz P (2015) Semantic visualization of Twitter usage in emergency and crisis situations. In: Lecture notes in business information processing, vol 233, pp 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24399-3_1/COVER

Paasi A (2016) Dancing on the graves: Independence, hot/banal nationalism and the mobilization of memory. Polit Geogr 54:21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POLGEO.2015.07.005

Pascual-Ferrá P, Alperstein N, Barnett DJ (2022) Social network analysis of COVID-19 public discourse on Twitter: implications for risk communication. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 16(2):561–569. https://doi.org/10.1017/DMP.2020.347

Pettit P (2002) Republicanism: a theory of freedom and government. Oxford University Press

Pulido CM, Redondo-Sama G, Sordé-Martí T, Flecha R (2018) Social impact in social media: a new method to evaluate the social impact of research. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203117

Räbiger S, Spiliopoulou M (2015) A framework for validating the merit of properties that predict the influence of a twitter user. Expert Syst Appl 42(5):2824–2834. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ESWA.2014.11.006

Ramdhani N, Anggraini R (2021) PDIP NTB political communication in building loyalty of cadres and constituents in elections. J Mantik 5(3):2081–2100

Rauschnabel PA, Sheldon P, Herzfeldt E (2019) What motivates users to hashtag on social media? Psychol Mark 36(5):473–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/MAR.21191

Restad HE (2020) What makes America great? Donald Trump, national identity, and US foreign policy. Glob Aff 6(1):21–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2020.1734955

Rocca GL (2020) Possible selves of a hashtag: moving from the theory of speech acts to cultural objects to interpret hashtags. Int J Sociol Anthropol 12(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJSA2019.0833

Roth S (2018) Introduction: contemporary counter-movements in the Age of Brexit and Trump. Sociol Res Online 23(2):496–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780418768828

Salomone RC (2022) The rise of English: global politics and the power of language. Oxford University Press

Sanawi JB, Samani MC, Taibi M (2017) #Vaccination: identifying influencers in the vaccination discussion on Twitter through social network visualisation Mus Chairil Samani. Int J Bus Soc 18:718–726

Santoso DH (2021) New media and nationalism in indonesia: An analysis of discursive nationalism in online news and social media after the 2019 indonesian presidential election. J Komun Malays J Commun 37(2):289–304. https://doi.org/10.17576/JKMJC-2021-3702-18

Sari DK, Ahmad J, Hergianasari P, Harnita PC, Wibowo NA (2021) Quantitative study of the cyber-nationalism spreading on Twitter with hashtag Indonesia and Malaysia using social network analysis. Media Watch J 12(1):161–171. https://doi.org/10.15655/mw/2021/v12i1/205465

Schertzer R, Woods E (2020) #Nationalism: the ethno-nationalist populism of Donald Trump’s Twitter communication. Ethn Racial Stud 44(7):1154–1173. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1713390

Schneider F (2022) Emergent nationalism in China’s sociotechnical networks: how technological affordance and complexity amplify digital nationalism. Nations Natl 28(1):267–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/NANA.12779

Schneider F (2018) Nationalism and its digital modes. In: China’s digital nationalism, pp 25–56. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190876791.003.0002

Schreiner T (2018) Information, opinion, or rumor? The role of Twitter during the post-electoral crisis in Côte d’Ivoire: Soc Media Soc https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118765736

Seman RAA, Laidey NM, Ali RS (2019) Netizens’ political engagement in Malaysia: impact of anti fake news act 2018. J Pengaj Media Malays 21(1):77–87. https://doi.org/10.22452/JPMM.VOL21NO1.6

Singenberger NP (2021) Review: the invention of tradition. Documenting the periphery. https://dlf.uzh.ch/sites/skandinavien-postkolonial/review-the-invention-of-tradition/

Small TA (2011) What the hashtag? Inf Commun Soc 14(6):872–895. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.554572

Smith MA, Shneiderman B, Milic-Frayling N, Rodrigues EM, Barash V, Dunne C, Capone T, Perer A, Gleave E (2009) Analyzing (social media) networks with NodeXL. https://www.cs.umd.edu/~ben/papers/Smith2009Analyzing.pdf

Smith AD (2010) Nationalism: theory, ideology, history. Polity

Squibb S (2016) This machine builds fascists: nationalism as mode of distribution. E-Flux J. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/78/82918/this-machine-builds-fascistsnationalism-as-mode-of-distribution/

Steinert-Threlkeld ZC (2018) Twitter as Data. Cambridge University Press

Stephens AC (2019) Feeling “Brexit”: nationalism and the affective politics of movement. GeoHumanit 5(2):405–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2019.1620623

Stolz S, Schlereth C (2021) Predicting tie strength with ego network structures. J Interact Mark 54:40–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INTMAR.2020.10.001

Stromer-Galley J (2019) Vulgar eloquence in the digital age. In: Power shift? Political leadership and social media, pp 34–48. Routledge

Tamir Y (2019) Not so civic: is there a difference between ethnic and civic nationalism? Annu Rev Polit Sci 2:419–434. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-022018

Tanasaldy T, Palmer C (2019) Discrimination, sport and nation building among Indonesian Chinese in the 1950s. Indones Malay World 47(137):47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639811.2019.1559564

Tong J, Zuo L (2021) The Brexit referendum on Twitter. Emerald Publishing Limited

Vessey R (2021) Nationalist language ideologies in tweets about the 2019 Canadian general election. Discourse Context Media 39:100447. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.DCM.2020.100447

Visoka G (2020) Everyday peace capture: nationalism and the dynamics of peace after violent conflict. Nations Natl 26(2):431–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/NANA.12591

Wang Z (2021) From crisis to nationalism? The conditioned effects of the COVID-19 crisis on neo-nationalism in Europe. Chin Polit Sci Rev 6:20–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-020-00169-8

Wang L, Zhong Q (2019) Research on the structures and features of netizens’ demand for popular science: a search data perspective. Cult Sci 2(2):129–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/209660831900200205

Webber J (2005) Independence day as a cosmopolitan moment: teaching international relations. Int Stud Perspect 6(3):374–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1528-3577.2005.00214.X

Wellman B (2001) Little boxes, glocalization, and networked individualism. In: Digital cities II: computational and sociological approaches. Kyoto workshop on digital cities. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-45636-8_2

White KB, Resmondo ZN, Jennings JC, Creel LM, Kelly Pryor BN (2022) A social network analysis of interorganisational collaboration: efforts to improve social connectedness. Health Soc Care Community. https://doi.org/10.1111/HSC.14044

Wicaksana GWI (2019) Economic nationalism for political legitimacy in Indonesia. J Int Relat Dev 24(1):27–50. https://doi.org/10.1057/S41268-019-00182-8

Wild C (2007) The radio midwife: Some thoughts on the role of broadcasting during the Indonesian struggle for independence. Indones Circ Sch Orient Afr Stud Newsl 19(55):34–42

Williamson W, Ruming K (2016) Using social network analysis to visualize the social-media networks of community groups: two case studies from Sydney. J Urban Technol 23(3):69–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2016.1197490

Wingfield-Hayes R (2022) Shinzo Abe death: Shock killing that could change Japan forever. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-62074223

Yan L, Pedraza-Martinez AJ (2019) Social media for disaster management: operational value of the social conversation. Prod Oper Manag 28(10):2514–2532. https://doi.org/10.1111/POMS.13064

Yang S, Keller FB, Zheng L (2020) Basics of social network analysis. In: Social network analysis: methods and examples, pp 2–25. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071802847.N1

Yu J, Muñoz-Justicia J (2020) Free and low-cost Twitter research software tools for social science. Soc Sci Comput Rev 40(1):124–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320904318

Żuk P, Żuk P (2022) The Independence Day as a nationalist ritual: framework of the March of Independence in Poland. Ethnography 23(1):14–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/14661381211073406

Funding

This project was funded by Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This paper was conceived and designed by DKS, WK, and NK. This paper was written by DKS. Data collection and data analysis were performed by DKS. The published manuscript has been reviewed and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sari, D.K., Kumorotomo, W. & Kurnia, N. Delivery structure of nationalism message on Twitter in the context of Indonesian netizens. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 12, 173 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-022-01006-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-022-01006-3