Abstract

Metabolic and storage diseases constitute a heterogeneous group of disorders that occur in the setting of altered biochemical homeostasis. Many of these disorders affect the lungs, either exclusively or as part of a systemic syndrome. For example, amyloidosis can be limited to the tracheobronchial tree or involve the kidneys, lungs and heart. The indolent course of some of these disorders and the non-specific clinical symptoms often result in a diagnostic challenge. Imaging, particularly high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), is an invaluable asset in the diagnosis of these clinical conditions. Some metabolic and storage diseases have characteristic HRCT appearances, helping narrow the differential diagnosis. Correlation of the radiological and histopathological findings of this group of diseases has also helped improve understanding of these disorders. In addition, CT can offer guidance when tissue sampling is warranted and aid in histopathological diagnosis. This article describes the pertinent clinical features of the more common metabolic and storage diseases affecting the lungs, illustrates their respective HRCT findings and provides the relevant differential diagnosis.

Teaching Points

-

• To recognise the various metabolic and storage lung diseases

-

• To identify the characteristic imaging findings in various metabolic and storage lung diseases

-

• To discuss the relevant differential diagnoses of each of these diseases

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic and storage diseases are a diverse group of conditions that are characterised by underlying biochemical or metabolic dysfunctions. Most of these diseases are uncommon or rare. Pulmonary disease in affected patients is most commonly a facet of systemic disease. The more common metabolic lung diseases include pulmonary calcification and ossification, pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis, pulmonary amyloidosis and pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP). Storage diseases are rare in most clinical practices, and patients usually present with multiorgan involvement. Pulmonary involvement in storage diseases occurs in Niemann-Pick disease, Gaucher disease and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome.

In this review, we describe the radiographic and high-resolution computerised tomography (HRCT) findings of these disorders and include discussion of pathophysiology, pertinent clinical features and the relevant different diagnosis. The key features of these metabolic and storage disorders are summarised in Tables 1 and 2, emphasising the value of clinical-radiological correlation in reaching an accurate diagnosis. Knowledge of these diseases and their respective imaging appearances is important for radiologists and clinicians, particularly those involved in respiratory care.

Metabolic lung diseases

HRCT technique

In patients with suspected metabolic or storage lung disease, HRCT should be done as a helical acquisition at end inspiration using the thinnest collimation and reconstructed at 1.0– to 1.5-mm slice thickness. The scan length should extend from the thoracic inlet down to the diaphragms. A high-spatial frequency kernel should be used for lung images. Contrast administration is not necessary. Technique should be standard for chest CT (typically 120 kV and automatic exposure control for mA). If significant air trapping is suspected, limited expiratory images can be obtained at 20-mm intervals from the apex to the diaphragm.

Pulmonary calcification and ossification

Introduction and clinical features

Pulmonary calcification and ossification are the most common metabolic lung diseases detected on chest radiography and HRCT. Pulmonary calcification occurs either through dystrophic or metastatic mechanisms [1]. Dystrophic calcifications form in damaged areas of lung as a result of inflammation or infection, such as tuberculosis, or in areas of previous haemorrhage or infarct. Calcification can also form in neoplasms such as chondrosarcoma or osteosarcoma as a natural process of the disease [2]. Metastatic pulmonary calcification develops in areas of normal lung in patients with altered calcium and phosphate metabolism, leading to calcium deposition in the lungs and other organs such as bones and kidneys. Hypercalcaemia secondary to chronic renal failure (Fig. 1) is the most common cause of metastatic pulmonary calcification [3]. Other causes include primary hyperparathyroidism, skeletal metastases and multiple myeloma [4]. The various causes are summarised in Table 3.

Diffuse pulmonary ossification has been increasingly recognised since the advent of CT [5]. Pathologically, pulmonary ossification can be classified as either nodular (NPO) or dendriform (DPO) based on the respective morphological appearances. Of the two entities, NPO is more common [6].

Nodular pulmonary ossification

Classically described with long-standing severe mitral stenosis, NPO can occur with any condition, leading to chronic pulmonary oedema and pulmonary venous hypertension [7, 8]. Histologically, NPO is characterised by calcified or ossified intra-alveolar masses that are usually devoid of marrow elements or fat [6].

Imaging findings

On radiography HRCT, small, discrete, round calcified nodules 1–5 mm in diameter are present in the mid to lower lungs (Fig. 2) [6]. The differential diagnosis in these patients includes healed varicella infection or remote disseminated granulomatous infections such as histoplasmosis.

A 54-year-old man with fibrosing mediastinitis, mitral valve stenosis and nodular pulmonary ossification. a Unenhanced HRCT image shows high attenuation ground-glass opacities in the right upper and lower lobes with punctate calcifications (arrowheads). b Unenhanced HRCT image shows soft tissue thickening and dense calcification (arrow) at the confluence of the right pulmonary veins

Dendriform pulmonary ossification

Although the exact pathogenesis of DPO is unclear, the condition is postulated to be a reaction to chronic lung insult, resulting in metaplasia of pulmonary fibroblasts into bone. In contrast to NPO, DPO predominantly affects the alveolar interstitium and usually contains marrow or fat elements [6]. DPO commonly develops in the setting of chronic inflammation, including interstitial fibrosis, and may also be seen in patients with a history of amyloidosis, cystic fibrosis, asbestos exposure or treatment with busulfan [9–12]. In the authors’ experience, recurrent aspiration also appears to be a risk factor. DPO is most common in men in their fifth and sixth decades of life. The clinical course is usually indolent or slowly progressive [13].

Imaging findings

The chest radiographic findings of DPO include delicate branching linear opacities and small distinct nodules. The differential diagnosis based on radiography includes fibrosis, bronchiectasis and lymphangitic spread of tumour. HRCT findings are quite characteristic, consisting of lower lobe predominant punctate and serpentine calcifications (Figs. 3, 4), often located in areas of co-existing lung disease such as fibrosis [11, 12].

Both NPO and DPO can show uptake of bone scanning agent (e.g. technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate) [14].

Definitive diagnosis and treatment

Since this disorder is usually incidentally detected and affected patients are asymptomatic, no treatment is recommended. Surveillance with pulmonary function tests or chest radiography may be considered, if deemed necessary.

Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis

Introduction and clinical features

Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis is a rare disease characterised by intra-alveolar deposition of microliths, which consist primarily of calcium and phosphorous [15]. The aetiology is unknown, although recent studies have found an autosomal recessive trait caused by mutations of the SLC34A2 gene in affected patients [16]. Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis occurs in all age groups. Most patients are asymptomatic, and the diagnosis is established during imaging studies for other conditions.

Imaging findings

On radiography, diffuse calcified micronodules are present in both lungs, leading to a “sandstorm” appearance [17]. These nodules are most prevalent in the mid to lower lungs, likely because of the increased surface area and blood supply [18, 19]. Interstitial thickening can also present, although this finding is clearer on HRCT. Radiography may also show a lucent subpleural line reflecting extrapleural fat between the ribs and the calcified lung, described as “the black pleura sign” [20].

HRCT shows discrete calcified micronodules scattered throughout the lungs. Apparent interlobular septal thickening and calcification may also be present (Fig. 5), presumably the result of increased concentration of microliths in the periphery of the secondary pulmonary lobule [21, 22]. Pleural and pericardial calcification has also been described [18, 23]. The differential diagnosis includes PAP, sarcoidosis, pneumoconiosis, idiopathic pulmonary haemosiderosis, amyloidosis and metastatic calcification [24, 25].

Bone scintigraphy can demonstrate radiotracer uptake in the lungs [26], and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can show increased signal intensity of the lesions on T1-weighted images [20].

Definitive diagnosis and treatment

Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis can be definitively diagnosed through bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy. There is no effective treatment for this condition, and prognosis is generally poor, with most patients experiencing worsening respiratory insufficiency [18]. Lung transplantation may be performed, although the long-term benefits are uncertain.

Pulmonary amyloidosis

Introduction and clinical features

Amyloidosis comprises a diverse group of metabolic disorders characterised by extracellular deposition of insoluble proteins consisting of beta-pleated sheets. Clinically, amyloidosis can be classified as either systemic or localised [27]. Systemic forms of amyloidosis include primary amyloidosis, secondary amyloidosis and familial amyloidosis. Primary amyloidosis occurs in the absence of pre-existing disease, with the exception of dyscrasias (e.g. multiple myeloma and Waldenström macroglobulinemia). Secondary amyloidosis, which is the more common form, results from a number of conditions, such as chronic renal failure, chronic infection and neoplasia. Localised forms are characterised by local production of fibrillar proteins (usually amyloid light chain [AL] type), which can be deposited in nearly any organ. Familial amyloidosis typically presents as sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy in the second or third decade of life [28]. The kidneys and heart can also be involved. In familial cardiac amyloidosis, the amyloid fibrils consist of prealbumin, a mutant of transthyretin.

Respiratory tract involvement occurs in approximately 50 % of patients with amyloidosis and is more common with the systemic form [27]. Clinical signs and symptoms vary depending on whether the disease is systemic or localised. The most common form of systemic amyloidosis, the AL form, is seen in patients over 50 years of age [29]. In this form, the clinical manifestations are variable as a result of multiorgan involvement, and patients may often present with non-specific symptoms such as fatigue or weight loss [30]. A substantial number of patients also have cardiac involvement that may contribute to respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea. Localised amyloidosis with involvement of the tracheobronchial system typically occurs in the fifth to sixth decades of life, and affected patients may present with stridor and dyspnea [31].

Imaging findings

Three CT patterns of pulmonary amyloidosis have been described: tracheobronchial, nodular parenchymal and diffuse interstitial forms.

Tracheobronchial form

The most common is the tracheobronchial form, which is characterised by submucosal deposition of fibrillar protein within the airway wall. This can manifest on CT as nodules, plaques or circumferential wall thickening [32, 33]. The larynx, trachea, and larger bronchi (Figs. 6, 7) may be involved. With this form, metaplastic calcification of the nodules is fairly common. Complications such as atelectasis and pneumonia are fairly common and are largely dependent on the site of involvement. In one study, obstructive symptoms were noted in patients with upper tracheal disease, whereas those with mid-tracheal and distal airway disease presented with recurrent pneumonias or lobar or distal atelectasis [31]. Also, patients with distal airway involvement may develop secondary bronchiectasis [31].

A significant advantage of HRCT in evaluation of tracheobronchial amyloidosis is the ability to accurately assess the degree of luminal narrowing. Using volumetric acquisitions and multiplanar reconstructions, airway luminal diameters and areas and extent of wall thickening can be accurately assessed. Also, HRCT can be used to guide bronchoscopic sampling and identify sites for treatment.

The differential diagnosis is limited and includes diffuse tracheal diseases such as relapsing polychondritis, granulomatosis with polyangitis, sarcoidosis and inflammatory bowel disease [34–37]. In contrast to other diffuse tracheal diseases, relapsing polychondritis characteristically spares the posterior tracheal and bronchial membranes. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica (TBO) is an uncommon condition characterised by formation of osseous, cartilaginous or both types of nodules within the large airways, and some reports in the literature have suggested that TBO may be associated with tracheobronchial amyloidosis [38]. As with relapsing polychondritis, TBO also spares the posterior airway membrane.

Nodular parenchymal form

Nodular parenchymal amyloidosis is relatively rare, with one study reporting only seven cases of nodular disease over a 13-year period [27]. It is characterised by solitary or multiple well-defined, predominantly subpleural nodules measuring up to 5 cm (Figs. 8, 9) [39]. These nodules are smoothly marginated and usually are slow growing. Cavitation may occur. As with the tracheobronchial form, calcification within the nodules is fairly common and is well depicted on HRCT [40]. The differential diagnosis is broad and includes granulomatous infection or neoplasia. An association with Sjögren syndrome has been described [41]. In these patients, HRCT can be helpful in assessing the nodules, as well as other manifestations such as randomly scattered cysts, bronchial wall thickening and bronchiectasis [42] (Fig. 10). Rarely, cystic lung disease can be seen in the absence of Sjögren syndrome (Fig. 11).

A 54-year-old man with nodular parenchymal amyloidosis. a Coronal reformatted HRCT image shows scattered punctate calcifications (arrowheads) in both lungs with patchy consolidation (arrows) in the right lung. In addition, a moderate right pleural effusion is noted. b Axial HRCT image shows punctate calcifications (arrowheads) in the lungs, a small right pleural effusion, and right paratracheal lymphadenopathy (arrow)

A man with Sjögren syndrome and amyloidosis. HRCT image shows multiple cysts (arrows) in both lower lobes, scattered nodules (arrowheads), and right lower lobe consolidation. The appearance is similar to that of lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, and the two processes may coexist in the setting of Sjögren syndrome

Diffuse interstitial form

Diffuse interstitial amyloidosis is the most rare form and is characterised by deposition of amyloid in the pulmonary interstitium. Most affected patients have systemic amyloidosis. HRCT findings in patients with this condition include reticulation and septal thickening (Fig. 12). Calcified or non-calcified micronodules may also be present [42]. Differential considerations include interstitial lung disease and neoplastic diseases including lymphangitic carcinomatosis.

Miscellaneous findings

Mediastinal and hilar lymph node enlargement can occur in isolation or as a component of systemic amyloidosis (Figs. 8b and 13) [27, 42]. Pleural involvement has also been reported, manifesting as pleural thickening and persistent pleural effusions (Fig. 12) [43].

Functional imaging with fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and amyloid scintigraphy with technetium-aprotinin has been shown to highlight areas of amyloid deposition, although the exact role of these techniques is still uncertain [44, 45].

Definitive diagnosis and treatment

The reference standard for diagnosing amyloidosis is histopathological confirmation of amyloid with Congo Red staining under cross-polarised light; with this staining, amyloid demonstrates apple-green birefringence [46]. Treatment and prognosis depend on the type and distribution of the disease, with localised forms usually managed conservatively and systemic forms treated with chemotherapy and anti-inflammatory agents. Patients with tracheobronchial disease may be treated with debulking or excision of the lesion(s).

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

Introduction and clinical features

PAP is a rare disease characterised by accumulation of surfactant-like material in the alveoli. The estimated incidence and prevalence of PAP is 3.7 per 1 million persons [47]. In patients with this disease, mutations in the surfactant protein or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) genes result in defective clearance of surfactant by alveolar macrophages [48]. Three forms of PAP are recognised: autoimmune, secondary and genetic. The autoimmune type (previously called primary or idiopathic) accounts for 90 % of all cases [49]. The more rare secondary form is usually associated with haematological malignancies and inhalation of toxins such as silica dust. The genetic type is exceedingly rare. In the autoimmune and secondary forms, clinical symptoms are non-specific, and nearly one-third of affected patients are asymptomatic. Most patients with PAP are young to middle-aged men [50]. An association of PAP with smoking has been described [50], and superimposed infections with Nocardia, Pneumocystis jiroveci and Mycobacteria have been reported [50, 51].

Imaging findings

Imaging findings of PAP can be striking; and the clinicoradiologic discordance with modest clinical symptoms and florid imaging findings has been described [48]. Chest radiography is a helpful initial imaging test for assessing patients with known or suspected PAP. Radiography typically shows bilateral patchy opacities with a perihilar to basal predominance (Fig. 14). The pattern is non-specific and can be easily mistaken for oedema and infection. However, ancillary findings associated with pulmonary oedema such as cardiomegaly and pleural effusion are usually absent. The onset of symptoms can also be used to distinguish PAP from pulmonary oedema, as PAP has an insidious onset, whereas pulmonary oedema and infection typically develop rapidly.

HRCT is the imaging test of choice for known or suspected PAP. The characteristic HRCT findings for PAP are patchy or geographic areas of ground-glass opacity with superimposed septal lines, termed “crazy-paving” (Figs. 14, 15) [52]. Although crazy-paving in and of itself is a non-specific finding, a geographic distribution in the correct clinical setting is virtually pathognomonic for PAP. One series reviewed the imaging findings of 98 patients with PAP [53]. Of the 89 patients who underwent chest radiography, 57 (58 %) had a perihilar distribution of disease, with costophrenic and apical sparing in 65 (73 %) patients. Of the 28 patients who underwent CT, crazy-paving was present in 20 (71 %) patients, and geographic or lobular areas of sparing were present in 15 (75 %) patients with the crazy-paving. Some reports describe coexisting interstitial fibrosis in patients with PAP [54, 55].

FDG-PET has been shown to show FDG uptake in PAP and is likely related to increased glucose utilisation in the inflammatory component [56].

Definitive diagnosis and treatment

PAP is definitively diagnosed by staining bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and lung biopsy is rarely required. Treatment depends on the type of PAP. Whole-lung lavage is the treatment of choice for symptomatic patients with autoimmune disease [48], and secondary cases require removal of the inciting agent. Experimental therapies with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and rituximab have been tried and have been successful in a subset of patients [57, 58].

Storage lung diseases

Gaucher disease

Introduction and clinical features

Gaucher disease, the most common lysosomal storage disorder, results from deficiency of the enzyme glucocerebrosidase [59]. Although this condition is rare worldwide, occurring in approximately 1 per 75,000 births, it occurs most frequently among Ashkenazi Jews [60]. Gaucher disease leads to the accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages (Gaucher cells) in a number of organs, particularly the liver, spleen, bone marrow and lung. Lung involvement is variable, although it has been reported in severe forms of the disease [61].

Imaging findings

When the interstitium is infiltrated with Gaucher cells, septal thickening may be present on HRCT (Fig. 16) [62]. A desquamative interstitial pneumonia-like reaction has also been described secondary to alveolar filling with Gaucher cells [63]. Plugging of the capillary walls can result in the pulmonary hypertension [64]. Furthermore, long-standing liver disease may predispose the patient to hepatopulmonary syndrome with intrapulmonary vascular dilation and arteriovenous shunting [65].

Definitive diagnosis and treatment

Bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy can be used for definitive diagnosis of lung involvement. In general, prognosis is poor, with more than half of patients dying of respiratory failure. Possible therapeutic options include enzyme therapy and substrate reduction therapy [66]. Patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome may have a worse prognosis [67].

Niemann-Pick disease

Introduction and clinical features

Niemann-Pick disease refers to a group of rare autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorders that are subclassified into types A, B, and C. Type A is the most common and has a high incidence in Ashkenazi Jews, where the carrier frequency is approximately 1 per 100 persons [60]. Types A and B are caused by absence or deficiency of sphingomyelinase, respectively. Patients with Type A usually die within a few years of birth, while type B patients with residual enzyme activity often survive into adulthood [68]. Type C disease is caused by mutations of NPC1 and NPC2 genes, which code for transmembrane proteins involved in Golgi shuttling and cholesterol binding [68]. Lung involvement typically occurs in all forms of the disease, with the possible exception of the adult form (type C) [69]. In patients with Niemann-Pick disease, lipid-laden macrophages called Niemann-Pick cells are deposited in various organs, including the lungs. In the lung, these cells infiltrate into and are deposited in the alveolar walls and interstitium with relative preservation of pulmonary architecture [68]. Most patients with this disease present during infancy [70].

Imaging findings

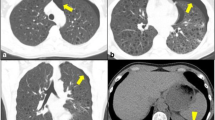

On HRCT, ground-glass opacity predominates in the upper lungs and interlobular septal thickening predominates in the lung bases (Fig. 17) with preservation of underlying lung architecture. Ground-glass opacity may reflect an endogenous lipoid pneumonia with partial alveolar filling (Fig. 18) [71], although the exact cause for the distribution of these findings is unclear [72].

A 46-year-old woman with Niemann-Pick disease. a HRCT image shows ground-glass opacity with septal thickening (arrowheads) in the upper lobes. Small pleural effusions are present. b HRCT image inferiorly at the level of heart again shows ground-glass opacity with septal thickening (arrowheads). Also seen are bilateral small pleural effusions and adjacent atelectasis (arrow)

Definitive diagnosis and treatment

Bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy can be used to demonstrate lung involvement by demonstrating the presence of characteristic Niemann-Pick cells. Treatment is generally supportive, although some reports have demonstrated the value of whole lung lavage in treating endogenous lipoid pneumonia [72]. Also, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been reported to be successful in treating lung disease [70].

Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome

Introduction and clinical features

Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (HPS) comprises a group of autosomal recessive disorders characterised by a triad of oculocutaneous albinism, platelet dysfunction with bleeding diathesis, and pulmonary disease [73]. Although this syndrome is rare worldwide, it has the highest prevalence in northwest Puerto Rico, affecting approximately 1 in 1,800 persons [74]. Seven different genes associated with HPS have been identified in humans [75]. The fundamental pathophysiology of this disease is disturbed formation or trafficking of intracellular vesicles such as lysosomes and melanosomes, resulting in intracellular accumulation of ceroid-lipofuscin [76]. Lung involvement in HPS is typically characterised by progressive pulmonary fibrosis. The cause of fibrosis is unclear, although it has been postulated to result from sequential injury to alveolar epithelium with the formation of lamellar bodies [77]. Specifically, researchers have explored the role of type II pneumocytes in this pathology [78].

Imaging findings

On HRCT, HPS manifests as reticulation, septal thickening, and ground-glass opacities, all of which can progress over time (Fig. 19). In advanced cases, peribronchovascular interstitial thickening has also been described [79]. A usual interstitial pneumonia pattern is typically present on histopathology [75].

Definitive diagnosis and treatment

Prognosis is poor in patients with lung fibrosis. There is no effective therapy for pulmonary fibrosis, although lung transplantation has been performed in selected patients [80].

Conclusion

In summary, metabolic and storage lung diseases consist of a heterogeneous group of entities with diverse and interesting clinical and imaging manifestations. Imaging findings can often be invaluable in narrowing the differential diagnoses and pointing towards a specific diagnosis in the right clinical setting. Also, imaging tests such as HRCT have a pivotal role in assessing disease progression and also in evaluating response to therapy.

References

Wang NS, Steele AA (1979) Pulmonary calcification: scanning electron microscopic and X-ray energy-dispersive analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 103(5):252–257

Bendayan D, Barziv Y, Kramer MR (2000) Pulmonary calcifications: a review. Respir Med 94(3):190–193

Kuhlman JE, Ren H, Hutchins GM, Fishman EK (1989) Fulminant pulmonary calcification complicating renal transplantation: CT demonstration. Radiology 173(2):459–460

Weber CK, Friedrich JM, Merkle E et al (1996) Reversible metastatic pulmonary calcification in a patient with multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol 72(5):329–332

Kanne JP, Godwin JD, Takasugi JE, Schmidt RA, Stern EJ (2004) Diffuse pulmonary ossification. J Thorac Imaging 19(2):98–102

Lara JF, Catroppo JF, Kim DU, da Costa D (2005) Dendriform pulmonary ossification, a form of diffuse pulmonary ossification: report of a 26-year autopsy experience. Arch Pathol Lab Med 129(3):348–353

Galloway RW, Epstein EJ, Coulshed N (1961) Pulmonary ossific nodules in mitral valve disease. Br Heart J 23:297–307

Woolley K, Stark P (1999) Pulmonary parenchymal manifestations of mitral valve disease. Radiographics 19(4):965–972

Fried ED, Godwin TA (1992) Extensive diffuse pulmonary ossification. Chest 102(5):1614–1615

Fernandez Crisosto CA, Quercia Arias O, Bustamante N, Moreno H, Uribe Echevarria A (2004) [Diffuse pulmonary ossification associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis]. Arch Bronconeumol 40(12):595–598

Gevenois PA, Abehsera M, Knoop C, Jacobovitz D, Estenne M (1994) Disseminated pulmonary ossification in end-stage pulmonary fibrosis: CT demonstration. AJR Am J Roentgenol 162(6):1303–1304

Chung MJ, Lee KS, Franquet T, Muller NL, Han J, Kwon OJ (2005) Metabolic lung disease: imaging and histopathologic findings. Eur J Radiol 54(2):233–245

Ahari JE, Delaney M (2007) Dendriform pulmonary ossification: a clinical diagnosis with 14year follow-up. Chest 132(4):701s

Silberstein EB, Vasavada PJ, Hawkins H (1985) Idiopathic pulmonary ossification with focal pulmonary uptake of technetium-99m HMDP bone scanning agent. Clin Nucl Med 10:436

Moran CA, Hochholzer L, Hasleton PS, Johnson FB, Koss MN (1997) Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. A clinicopathologic and chemical analysis of seven cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 121(6):607–611

Tachibana T, Hagiwara K, Johkoh T (2009) Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: review and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med 15(5):486–490

Balikian JP, Fuleihan FJ, Nucho CN (1968) Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: report of five cases with special reference to roentgen manifestations. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 103(3):509–518

Gasparetto EL, Tazoniero P, Escuissato DL, Marchiori E, Frare E, Silva RL, Sakamoto D (2004) Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis presenting with crazy-paving pattern on high resolution CT. Br J Radiol 77(923):974–976

Spencer H (1984) Pathology of the lung, 4th edn. Pergamon, London, pp 740–744

Hoshino H, Koba H, Inomata S et al (1998) Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: high-resolution CT and MR findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 22(2):245–248.8

Korn MA, Schurawitzki H, Klepetko W, Burghuber OC (1992) Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: findings on high-resolution CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 158(5):981–982

Deniz O, Ors F, Tozkoparan E et al (2005) High resolution computed tomographic features of pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. Eur J Radiol 55(3):452–460

Verma BN (1963) Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis in a child of thirteen years. Br J Dis Chest 57:213–215

Weinstein DS (1999) Pulmonary sarcoidosis: calcified micronodular pattern simulating pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. J Thorac Imaging 14(3):218–220

Saputo V, Zocchi M, Mancosu M, Bonaldi U, Croce P (1979) Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: a case report with a discussion of differential diagnosis. Helv Paediatr Acta 34(3):245–255

Coolens JL, Devos P, De Roo M (1985) Diffuse pulmonary uptake of 99mTc bone-imaging agents: case report and survey. Eur J Nucl Med 11(1):36–42

Utz JP, Swensen SJ, Gertz MA (1996) Pulmonary amyloidosis: the Mayo Clinic experience from 1980 to 1993. Ann Intern Med 124(4):407–413

Kyle RA (1995) Amyloidosis. Circulation 91(4):1269–1271

Kyle RA, Gertz MA (1995) Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol 32(1):45–59

Gertz MA, Kyle RA (1989) Primary systemic amyloidosis: a diagnostic primer. Mayo Clin Proc 64(12):1505–1519

O’Regan A, Felon HM, Beamis JF Jr, Steele MP, Skinner M, Berk JL (2000) Tracheobronchial amyloidosis: the Boston University experience from 1984 to 1999. Med (Baltimore) 79(2):69–79

Kirchner J, Jacobi V, Kardos P, Kollath J (1998) CT findings in extensive tracheobronchial amyloidosis. Eur Radiol 8(3):352–354

Kim HY, Im JG, Song KS et al (1999) Localized amyloidosis of the respiratory system: CT features. J Comput Assist Tomogr 23(4):627–631

Kwong JS, Muller NL, Miller RR (1992) Diseases of the trachea and main-stem bronchi: correlation of CT with pathologic findings. Radiographics 12(4):645–657

Kwong JS, Adler BD, Padley SP, Muller NL (1993) Diagnosis of diseases of the trachea and main bronchi: chest radiography vs CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 161(3):519–522

Ohkubo Y, Narimatsu A, Higuchi M et al (1990) [CT findings of the benign tracheobronchial lesions with calcification]. Rinsho Hoshasen 35(7):839–846

Im JG, Chung JW, Han SK, Han MC, Kim CW (1988) CT manifestations of tracheobronchial involvement in relapsing polychondritis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 12(5):792–793

Sakula A (1968) Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: its relationship to primary tracheobronchial amyloidosis. Thorax 23(1):105–110

Aylwin AC, Gishen P, Copley SJ (2005) Imaging appearance of thoracic amyloidosis. J Thorac Imaging 20(1):41–46

Himmelfarb E, Wells S, Rabinowitz JG (1977) The radiologic spectrum of cardiopulmonary amyloidosis. Chest 72(3):327–332

Jeong YJ, Lee KS, Chung MP et al (2004) Amyloidosis and lymphoproliferative disease in Sjögren syndrome: thin-section computed tomography findings and histopathologic comparisons. J Comput Assist Tomogr 28(6):776–781

Pickford HA, Swensen SJ, Utz JP (1997) Thoracic cross-sectional imaging of amyloidosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 168(2):351–355

Aichaouia C, Ben Meftah MR, M’hamdi S et al (2010) Pleural amyloidosis attesting to generalised amyloidosis]. Rev Pneumol Clin 66(3):204–208

Mekinian A, Jaccard A, Soussan M, Launay D, Berthier S, Federici L, Lefèvre G, Valeyre D, Dhote R, Fain O (2012) 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with amyloid light-chain amyloidosis: case-series and literature review. Amyloid 19(2):94–98

Schaadt BK, Hendel HW, Gimsing P, Jønsson V, Pedersen H, Hesse B (2000) 99mTc aprotinin scintigraphy in amyloidosis. J Nucl Med 44(2):177–183

Pinney JH, Hawkins PN (2012) Amyloidosis. Ann Clin Biochem 49(Pt 3):229–241

Ben Dov I, Kishinevski Y, Roznman J et al (1999) Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis Israel: ethnic clustering. Isr Med Assoc J 1(2):75–78

Ioachimescu OC, Kavuru MS (2006) Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Chron Respir Dis 3(3):149–159

Inoue Y, Trapnell BC, Tazawa R et al (2008) Japanese Center of the Rare Lung Diseases Consortium. Characteristics of a large cohort of patients with autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in Japan. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177(7):752–762

Seymour JF, Presneill JJ (2002) Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: progress in the first 44years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166(2):215–235

Burbank B, Morrione TG, Cutler SS (1960) Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and nocardiosis. Am J Med 28:1002–1007

Murch CR, Carr DH (1989) Computed tomography appearances of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Clin Radiol 40(3):240–243

Frazier AA, Franks TJ, Cooke EO, Mohammed TL, Pugatch RD, Galvin JR (2008) From the archives of the AFIP: pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Radiographics 28(3):883–899

Miller PA, Ravin CE, Smith GJ, Osborne DR (1981) Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis with interstitial involvement. AJR Am J Roentgenol 137(5):1069–1071

Clague HW, Wallace AC, Morgan WK (1983) Pulmonary interstitial fibrosis associated with alveolar proteinosis. Thorax 38(11):865–866

Hsu CW, Liu FY, Wang CW, Lin HC, Huang CD (2009) F-18 FDG PET/CT in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Clin Nucl Med 34(2):103–104

Venkateshiah SB, Yan TD, Bonfield TL, Thomassen MJ, Meziane M, Czich C, Kavuru MS (2006) An open-label trial of granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor therapy for moderate symptomatic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Chest 130(1):227–237

Kavuru MS, Malur A, Marshall I et al (2011) An open-label trial of rituximab therapy in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Eur Respir J 38(6):1361–1367

Cox TM (2001) Gaucher disease: understanding the molecular pathogenesis of sphingolipidoses. J Inherit Metab Dis 24(Suppl 2):106–121

Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, Carey WF (1999) Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. JAMA 281(3):249–254

Goitein O, Elstein D, Abrahamov A et al (2001) Lung involvement and enzyme replacement therapy in Gaucher’s disease. QJM 94(8):407–415

Yassa NA, Wilcox AG (1998) High-resolution CT pulmonary findings in adults with Gaucher’s disease. Clin Imaging 22(5):339–342

Copley SJ, Coren M, Nicholson AG, Rubens MB, Bush A, Hansell DM (2000) Diagnostic accuracy of thin-section CT and chest radiography of pediatric interstitial lung disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 174(2):549–554

Roberts WC, Frederickson DS (1967) Gaucher’s disease of the lung causing severe pulmonary hypertension with associated acute recurrent pericarditis. Circulation 35(4):783–789

Kim JH, Park CH, Pai MS, Hahn MH, Kim HJ (1999) Hepatopulmonary syndrome in Gaucher disease with right-to-left shunt: evaluation and measurement using Tc-99m MAA. Clin Nucl Med 24(3):164–166

Gülhan B, Özçelik U, Gürakan F et al (2012) Different features of lung involvement in Niemann-Pick disease and Gaucher disease. Respir Med 106:1278–1285

Lo S, Liu J, Chen F et al (2011) Pulmonary vascular disease in Gaucher disease: clinical spectrum, determinants of phenotype and long-term outcomes of therapy. J Inherit Metab Dis 34(3):643–650

Nicholson AG, Florio R, Hansell DM et al (2006) Pulmonary involvement by Niemann-Pick disease. A report of six cases. Histopathology 48(5):596–603

Sevin M, Lesca G, Baumann N et al (2007) The adult form of Niemann-Pick disease type C. Brain 130(Pt 1):120–133

Skikne MI, Prinsloo I, Webster I (1972) Electron microscopy of lung in Niemann-Pick disease. J Pathol 106(2):119–122

Ferretti GR, Lantuejoul S, Brambilla E, Coulomb M (1996) Case report. Pulmonary involvement in Niemann-Pick disease subtype B: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 20(6):990–992

Nicholson AG, Wells AU, Hooper J et al (2002) Successful treatment of endogenous lipoid pneumonia due to Niemann–Pick type B disease with whole-lung lavage. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165(1):128–131

Hermansky F, Pudlak P (1959) Albinism associated with hemorrhagic diathesis and unusual pigmented reticular cells in the bone marrow: report of two cases with histochemical studies. Blood 14(2):162–169

Witkop CJ, Nunez Babcock M, Rao GH et al (1990) Albinism and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome in Puerto Rico. Bol Assoc Med PR 82(8):333–339

Pierson DM, Ionescu D, Qing G et al (2006) Pulmonary fibrosis in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. A case report and review. Respiration 73(3):382–395

Huizing M, Gahl WA (2002) Disorders of vesicles of lysosomal lineage: the Hermansky-Pudlak syndromes. Curr Mol Med 2(5):451–467

Nakatani Y, Nakamura N, Sano J et al (2000) Interstitial pneumonia in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome: significance of florid foamy swelling/degeneration (giant lamellar body degeneration) of type-2 pneumocytes. Virchows Arch 437(3):304–313

Mahavadi P, Guenther A, Gochuico BR (2012) Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome interstitial pneumonia: it’s the epithelium, stupid! Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186(10):939–940

Avila NA, Brantly M, Premkumar A, Huizing M, Dwyer A, Gahl WA (2002) Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome: radiography and CT of the chest compared with pulmonary function tests and genetic studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol 179(4):887–892

Lederer DJ, Kawut SM, Sonett JR, Vakiani E, Seward SL, White JG, Wilt JS, Marboe CC, Gahl WA, Arcasoy SM (2005) Successful bilateral lung transplantation for pulmonary fibrosis associated with Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. J Heart Lung Transplant 24:1697–1699

Acknowledgement

We thank Megan M. Griffiths, scientific writer for the Imaging Institute, Cleveland Clinic, for her editorial assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Renapurkar, R.D., Kanne, J.P. Metabolic and storage lung diseases: spectrum of imaging appearances. Insights Imaging 4, 773–785 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-013-0289-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-013-0289-x