Abstract

This paper investigates how much of the current account adjustment after the global financial crisis in Spain can be explained by cyclical factors. For this purpose, we extend the IMF’s external balance assessment methodology to allow for country-specific slopes and intercepts. The good fit of these cross-country regressions implies negligible residuals for most countries, and, as a result, the positive analysis of current account decompositions provides a more informative assessment of the external balance drivers. According to our findings, around 60% of the 11 pp. adjustment of the Spanish external imbalance over the years 2008–2015 can be explained by transitory factors such as the output gap, the oil balance, and the financial cycle—a share that diminished down to 50% during the more recent recovery period. The remaining adjustment of the Spanish external balance is explained by factors such as the cyclically adjusted fiscal consolidation, population ageing, lower growth expectations, or competitiveness gains, which can all be considered as more permanent phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the years that preceded the outburst of the global crisis, the Spanish current account balance experienced a strong deterioration, reaching its historical minimum in 2007 (Fig. 1). The correction that followed, from almost − 10% of GDP in 2007 to around \(+\) 2.0% in 2016 and the years thereafter, represented an unprecedented adjustment over the last 150 years.

Despite this strong adjustment, the Spanish economy was left with a high burden of external debt, accumulated mostly in the pre-crisis period. At the end of 2019, gross external debt amounted to 169.3% of GDP. In this context, any deterioration in the conditions of access to external financing could affect financial stability, despite the recent shift in the composition of Spanish external liabilities towards longer maturities. There is quite a strong consensus that mitigating these risks requires the Spanish economy to maintain sustained current account surpluses in the upcoming years.

In light of these issues, one important concern is whether current external surpluses are likely to revert in the medium term. This could happen if the current account adjustment observed in the post-crisis years was mostly driven by cyclical factors, whose dynamics could change in the next years. For instance, Spanish domestic demand and imports having contracted, the negative output gap of the post-crisis period has likely contributed to the reduction of the external deficit. By the same token, exceptionally low oil prices might have contributed to improving the energy balance, with a positive effect on the current account. To the extent that this oil price trend will reverse and as the output gap will close, in the medium term, a part of the adjustment observed in the Spanish current account after the crisis might well unravel, and the ability to generate sustained external surpluses in the future might be reduced.

The question we address in this paper is precisely how much of the observed adjustment in the Spanish current account was due to cyclical factors, such as the output gap and oil price dynamics, and which part should be related instead to determinants that could be of a more permanent nature. Shedding light on the relative importance of short-term and structural determinants in driving the dynamics of the Spanish current account is of twofold importance. On the one hand, it is useful to figure out if a relevant share of the adjustment is likely to vanish or even revert in the medium term, in which the impact of cyclical determinants may be muted. On the other hand, disentangling the impact of the different drivers of the current account will provide a guidance on the margins through which the government can intervene to induce corrections in the external balance, in order to meet any desired target in terms of external debt.

To this aim, in the spirit of the external balance assessment (EBA) methodology, used by the IMF to investigate the drivers of countries’ current account balances and to assess the desirability of their external positions (IMF 2013), we regress countries’ current accounts on a wide set of possible drivers, including cyclical factors (such as the output gap) and more structural determinants (such as demographics). The estimated coefficients can then be used to compute the contribution of each driver to the current account dynamics of each country. In contrast to the homogeneity assumption in original EBA-type regressions, we allow for country-specific slopes and intercepts. This permits, on the one hand, to reduce the large residuals that EBA regressions generally deliver and to lower the unexplained share of current account fluctuations.

On the other hand, country-specific slopes allow us to fully account for cross-country heterogeneity in the response of external balances to their drivers—heterogeneity that, as documented by the literature and as we confirm in the empirical section of this paper, seems to be validated by the data. Indeed, several contributions have shown that the impact of current account drivers on external balances may differ across countries. For instance, macroeconomic uncertainty increases more precautionary savings in low and medium-income economies, whose safety nets are less developed. Fiscal shocks have a stronger impact on the current account of developing countries, as less-developed internal financial markets and a higher share of hand-to-mouth consumers are likely to make Ricardian equivalence less likely to hold. Demographic factors related to ageing have been shown to have a significant effect only on economies whose population is ageing fast enough.Footnote 1 Also cyclical factors, such as the output gap and oil prices, can have a different impact on external balances depending on the structural characteristics of the economy. For instance, a cyclical increase in relative income, as captured by the output gap, should raise domestic consumption expenditure depending on agents’ marginal propensity to consume, which can differ among countries. Also, how much a rise in expenditure affects imports and, ultimately, external balances, is likely to depend on the structural characteristics of the economies, such as the propensity to orient expenditure towards domestically produced goods (home bias in consumption) or trade elasticity, features that, as several empirical works show, are rather persistent and might display relevant difference across countries.Footnote 2 As concerns the impact of oil price fluctuations on external balances, relevant differences may exist across countries depending on their production structure and their degree of dependency on external energy sources. More generally, Desbordes et al. (2017) show that EBA coefficients tend to be different in OECD and non-OECD economies, so that the two groups of countries cannot be pooled together. Our approach, which consists in estimating EBA-type regressions with country-specific coefficients, allows to take all these sources of cross-country heterogeneity fully into account.

According to our findings, most of the external deficit accumulated over the expansionary years 1995–2007 (around 90%) can be attributed to cyclical factors, namely the positive output gap, increasing oil prices, and the lax conditions in global financial markets. This share is much lower when we look at the contractionary post-crisis phase. Indeed, around 60% of the 11 pp. adjustment of the Spanish current account balance between 2008 and 2015 can be explained by cyclical drivers, such as the negative output gap and the low price of oil. The share of the adjustment related to transitory factors diminished further in the following years, reaching 50% in 2018. The remaining correction in the Spanish current account is explained by factors of a more structural nature. Among these, the strong reduction in the deficit of the public sector observed in the post-crisis years, which, in the absence of an opposite adjustment of the private sector, contributed strongly to the correction of the external deficit. Also, a decrease, in relation to other countries, in the share of the population older than 65 tended to raise external savings. A similar effect had the increase in long-term interest rates with respect to other countries, which had a contractionary effect on the economy. Lower growth expectations also led to lower investment and contributed to reducing external borrowing.

All in all, we conclude that these factors explain the structural change in the Spanish economy external balance after the global financial crisis. For the first time in recent history, this change makes compatible positive output gaps with sustained external surpluses. We deem this feature as crucial to alleviate the vulnerability that the high level of external debt represents to the Spanish economy.

This paper is related to the vast literature that studies the dynamics of national current account balances, especially those of Southern European debtor economies, in recent years in order to determine the factors behind their deterioration in the period that led to the crisis and the determinants that contributed instead to the subsequent marked correction. Among these works, the econometric analysis of Atoyan et al. (2013) found that fiscal consolidation was one of the elements that explained the post-crisis external adjustment in Southern European debtor economies, in line with our findings. Cheung et al. (2010) panel analysis—using data up to 2008 and assuming homogenous coefficients—finds that in the first phase of the crisis a large share of current account adjustment was due to cyclical factors, at least for the main economies. Ollivaud and Schwellnus (2013) run panel current account regressions allowing for area-specific coefficients. According to their results, the business and housing cycles account for around a half of the decline in external imbalances in Eurozone debtor countries between 2008 and 2012. Tressel and Wang (2014) use, similarly to us, a regression approach based on the EBA method. They find that both cyclical and structural factors contributed to the adjustment of Southern European countries. In particular, for Spain they estimate that only 27% of the adjustment between 2007 and 2012 was cyclical. A similar result was obtained by the study of the European Commission (2014). According to ECB (2014), less than half of the adjustment of the Spanish current account up to 2012 was due to the negative output gap. With respect to these studies, in our analysis we exploit data up to 2018, which permits evaluating how external consolidations proceeded after the first phase of the crisis and studying the impact of the fiscal consolidation on the Spanish economy, which started to deliver its effect in 2013. We also document that the assumption of slope homogeneity used in most of these analyses seems not to be supported by the data. Allowing for full heterogeneity between countries in the response of the current account to its drivers generally leads us to estimate a higher responsiveness of the Spanish current account to temporary factors, especially to the output gap.

The next section describes the cross-country regressions considered by the EBA methodology and investigates whether the assumption of slope homogeneity implicit in these regressions is supported by the data. Section 3 describes the dataset. Section 4 identifies how much of the current account dynamics of the Spanish economy up to 2015 can be attributed to cyclical and structural factors. Section 5 carries out a similar analysis on the main sub-balances, namely the trade and the investment income balance. Section 6 extends our baseline decompositions to cover the more recent period 2016–2018. We draw some conclusions in Sect. 6.

2 The country-specific EBA methodology

The external balance assessment (EBA) methodology is a widely used tool for assessing the importance of different current account determinants in shaping external imbalances across countries (see IMF 2013). Despite the EBA approach consider different tools for assessing the external position of different countries, we focus here on the current account regressions that can be used to assess which part of a country’s external balance is explained by structural determinants (such as demographic factors) and temporary factors (such as the output gap) in a multilateral context. The regressions of the current account balance on a multitude of explanatory factors in a panel of countries provides coefficients for determinants, which in turn allow for computing their contribution to the current account balance of a particular country. Such regressions consider both the trade perspective (through factors such as competitiveness) and the savings–investment perspective since the current account balance equals the difference between aggregate saving and investment (through the drivers of net saving such as demographics).

To be more concrete, the EBA approach is used for two different purposes: on the one hand, the positive analysis allows identifying the main drivers of current account developments; on the other hand, the normative arm estimates the so-called current account norms, which are interpreted by the IMF as the desirable levels of external imbalance for each country. The normative component requires strong judgement on certain policy aspects such as the desirable fiscal deficit in a given country when determining the so-called policy benchmarks. Moreover, in order to ensure multilateral consistency, it requires the use of panel approaches fully ignoring country-specific heterogeneity. As a result, the general feature of such panel regressions is that they leave a substantial part of current account balances unexplained, i.e. the residuals of such regressions are typically large. These residuals can be attributed to factors that have not yet been accounted for, which may be permanent or transitory.

Our analysis here is based on the positive side of the EBA methodology so that we fully abstract from normative considerations. In particular, we aim to decompose current accounts into permanent and transitory factors without judgments about the equilibrium or norms for external imbalances. Along these lines, the inclusion of country-specific effects represents a natural extension as they can be considered as permanent by definition. Also, its inclusion in the panel regressions improves the estimated elasticities of fundamental factors by removing omitted variable bias.

More formally, we estimate the following empirical model:

where \(CA_{it}\) refers to the current account balance of country i in year t. \(x_{it,S}\) is a vector of structural or permanent factors (e.g. demographic indicators, institutional quality, growth expectations) while \(x_{it,C}\) includes the set of cyclical factors (e.g. output gap or oil prices). \(\eta _i\) refers to country-specific heterogeneity that is permanent and unobserved. Finally, the right-hand-side variables are included in deviations from the GDP-weighted world average in a given year.Footnote 3

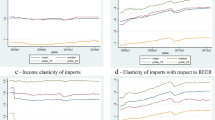

Crucially, the estimated coefficients are also allowed to vary across countries (\(\beta _{i,S}\) and \(\beta _{i,C}\)) as it is apparent from Eq. (1). Panel 1 of Fig. 2 plots the estimated elasticity of the current account to the output gap for each country in our sample. The graph illustrates how these elasticities widely differ across countries, ranging from − 1.42 for Switzerland to 0.43 for Canada. As a result, Panel 2 of Fig. 2 illustrates how this heterogeneity explains the large residuals that plague EBA regressions and hamper the interpretation of the positive decompositions of current account balances.

In order to formally test the validity of the slope homogeneity assumption, we use the test proposed by Pesaran and Yamagata (2008), which is based on a version of the Swamy (1970) F-test adjusted to provide valid inference when both N and T are large.Footnote 4 Table 1 reports the Pesaran and Yamagata (2008) homogeneity test for a panel regression of the current account on the following factors: output gap, private credit, old-age dependency ratio, expected GDP growth, long-run interest rate, unit labour costs, structural fiscal deficit, exhaustible resources of oil and natural gas, oil prices, financial cycle, and institutional environment (see below for details on the selection of variables). The verdict of this test corroborates the intuition from Fig. 2, i.e. the null hypothesis of slope homogeneity is sharply at odds with the data. Therefore, the homogeneity assumption implicitly made by the original EBA regressions appears to be rejected by the data.

The mean group estimator by Pesaran and Smith (1995) allows the inclusion of time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity at the country level as well as country-specific slopes. Mean group-type estimators allow for heterogeneity by running country-specific regressions and then averaging the coefficients across the panel. This provides the researcher with well-behaved slopes as long as both N and T are moderate. Moreover, the residuals can be estimated using the country-specific slopes and intercepts so that they are negligible in most cases. In other words, country-specific regressions provide a much better fit of the data than panel-wide alternatives and thus allow for a more informative decomposition of current accounts between permanent and transitory factors.

Turning to identification, most of the regressors may be subject to reverse causality concerns. However, we follow the approach that is common in the literature based on the assumption of exogeneity of the right-hand-side variables at the yearly frequency. Despite we acknowledge the limitations of our identification strategy, one can think of an alternative interpretation to our coefficient estimates as weights used to interpret current accounts as weighted averages of transitory and permanent factors. This interpretation is particularly appealing in light of the stationarity of all the variables together with the high R2 of our regressions that render negligible the unobserved residuals.

The consideration of the mean group estimator precludes the inclusion of all the factors included in the original EBA regression. First, those variables presenting unit roots cannot be included in the model to avoid spurious regression in country-specific regressions. Second, since full slope heterogeneity across countries is allowed by construction, it is not necessary to include interaction terms. Third, regressors without time variation cannot be considered because identification relies on within-country variation. In light of these considerations, we now turn to the discussion of the final set of variables included in our analysis.

3 Data

The majority of our data are taken from the IMF EBA dataset, which provides a wide set of potential current account determinants for 49 advanced and emerging market economies for the period 1986–2015. In particular the dataset includes fundamental non-policy-related determinants (such as productivity, expected GDP growth, demographic factors), financial determinants (countries’ reserve currency status, global financial market conditions), cyclical factors (such as the output gap) and policy-related variables (like the cyclically adjusted fiscal balance and the level of public expenditure in health). Our specification for current account regressions starts from the EBA baseline. Yet, as mentioned above, since we consider country-specific slopes and intercepts, in our baseline specification we drop interacted variables as well as dummies with no within-country variation. We also drop variables for which we detect unit roots. We then include additional variables in order to account for the features that characterize the Spanish experience over the last years: low oil prices in an economy depending on oil imports as well as competitiveness gains. As a result, our baseline specification for current account regressions includes the following variables:

-

output gap, based on estimates from IMF country teams or on HP filtered estimates;

-

oil and natural gas balance: net exports of oil and gas as a share of GDP. Enters only when the balance is positive and is adjusted for a measure of temporariness to take into account whether the resource is expected to be exhausted soon;

-

oil price: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Crude Oil Prices taken from FRED economic data;

-

VIX index: CBOE Volatility Index, reflects implicit volatility of S&P 500 index options, calculated and published by the Chicago board options exchange (CBOE). Is interpreted as a measure of global risk aversion;

-

unit labour costs: labour income share multiplied by GDP deflator. Sources: Penn World Tables and IMF WEO;

-

interest rates: real long-term interest rates. Source: IMF IFS;

-

expected GDP growth: WEO projections of real GDP growth 5 years ahead;

-

old-age dependency ratio: population aged over 65 divided by population between 30 and 64 years old;

-

fiscal balance: cyclically adjusted fiscal balance computed based on IMF country team estimates. Due to potential endogeneity issues, the EBA dataset provides the instrumented value of this variable. See IMF (2013) for the list of instruments used.

-

private credit as a share of GDP: credit provided to the non-financial private sector by domestic financial institutions. Demeaned;

-

risks associated with the institutional environment. average of 5 indicators from the International Country Risk Guide dataset. Higher values signal lower risk.

All variables except oil prices and the VIX index are expressed relative to a GDP-weighted world aggregate. The source is the EBA dataset, unless otherwise specified.

4 Current account determinants: cyclical versus structural

The purpose of this section is to estimate a decomposition of current account balances into a transitory/cyclical component and a permanent/structural component. Labelling as permanent or transitory the contributions of the determinants included in our analysis poses a challenge. In particular, our baseline decomposition considers as cyclical the contribution of output gaps, financial cycle, and oil prices and balance. The remaining factors are labelled as more permanent or structural, namely private credit—driven by growth expectations, old-age dependency ratio, expected GDP growth, long-run interest rate, unit labour costs, structural fiscal deficit, and institutional environment.

Table 2 reports different country-specific EBA regressions based on the empirical model in Eq. (1). These coefficient estimates are then used to decompose the current account into permanent and transitory components. While column (1) shows the average estimates across all the countries in the sample, our decompositions will be based on country-specific estimates for Spain reported in column (2) that better capture the contribution of each factor to current account developments as illustrated in Fig. 2. Indeed, residuals are almost negligible in most countries when using the country-specific estimates as illustrated by the high R-squared.

Estimates for Spain in column (2) present the expected signs. The negative and statistically significant coefficient for the output gap reflects the fact that recessions are typically associated with lower domestic demand. According to our estimates, an increase in the Spanish output gap by 1% point is associated with a decline of the current account by about 0.65% of GDP, which stands clearly above the average reported in column (1). Turning to the other transitory factor included in the regression, the oil and gas balance together with oil prices capture the impact of fluctuations in the oil price given the different extent of oil intensity in production and relatively inelastic demand in net oil importers such as Spain. Our estimates in column (2) suggest that the net oil and gas trade balance has a positive and significant effect while oil prices per se present a negative but only marginally significant (p value 0.15) effect. With respect to the financial cycle, proxied by the VIX index, the estimated effect is positive and significant in the case of the Spanish economy. This could reflect either the greater ability to borrow from abroad in times of high global liquidity or the role as safe-haven asset of the Euro in times of financial turmoil, which would reduce the payments on Spanish external debt in times of global crisis.

Lower relative unit labour costs are typically associated with improved terms of trade that may induce expenditure switching and thus a more positive current account balance. Our estimates in column (2) confirm this hypothesis in the case of Spain as the estimated effect is negative and statistically significant. Turning to the interest rate, its effect is uncertain ex ante because higher interest rates induce exchange rate appreciation (with a negative impact on the current account) as well as lower domestic demand due to their contractionary impact on the economy (with a positive effect on the current account). In light of the estimates in column (2), the contractionary effect appears to dominate in Spain as the coefficient is positive and significant.

As expected from economic theory, the impact of the old-age dependency ratio on the current account balance is estimated to be negative and significant because retirees typically draw down their savings. The relative fiscal balance presents the expected positive coefficient as the saving—investment decisions of the public sector are also reflected in the overall economy given the many factors that can induce a departure from Ricardian Equivalence (see Lane and Milesi-Ferretti 2002). Countries with high expected GDP growth may attract international capital flows reducing their current accounts because they are expected to produce higher rates of return; the negative and significant effect of this factor confirms the role of expectations of future growth as a major driver of current account behaviour in the case of Spain.

Weak institutions lower the risk-adjusted return to capital and thus generate a disincentive to investment and possibly an incentive to save more (Alfaro et al. 2005); this channel is reflected in the negative and significant coefficient of our institutional environment variable (higher values signify less risk). Private credit/GDP is considered as an indirect indicator of policies to contain financial excesses. Improved financial deepening may result in lower saving rates and higher investment; however, financial development may also encourage savings by lowering transaction costs and facilitating risk management, implying a positive influence on the current account (see Cheung et al. 2010). The latter effect appears to dominate in Spain given the positive and significant coefficient associated to private credit in column (2) despite the negative average effect in column (1).

In columns (3)–(6) of Table 2, we report several robustness checks. In column (3) we follow IMF (2013) and consider a GLS estimator with an AR(1) correction that accounts for within-country autocorrelation in current accounts. In particular, the Prais and Winsten (1954) estimator considers a transformation of the original model such that the resulting disturbances are iid provided the original ones present serial correlation of type AR(1). The estimates in column (3) confirm that the results are barely affected by the potential autocorrelation in the current account shocks.

Columns (4) and (5) are based on model averaging approaches that provide standard errors incorporating not only parameter uncertainty but also model uncertainty. Model uncertainty results from the lack of theoretical guidance on the particular regressors to include in the empirical model. When model uncertainty is present, traditional standard errors would underestimate the real uncertainty associated to the estimate of interest because variation across models is ignored. In order to account for both levels of uncertainty, model averaging techniques estimate all possible combinations of regressors and constructs a single estimate by averaging all model-specific estimates. We consider two alternative prior structures for the sake of robustness, namely Laplace-type priors (WALS) and unit information priors (BMA)—see Moral-Benito (2015) for an in-depth analysis of model averaging. Overall, the main conclusions from column (2) remain robust when model uncertainty is taken into account.

In order to gauge the magnitude of the contributions of each factor to current account fluctuations, column (6) of Table 2 reports the coefficients from a regression of current account on the standardized regressors (zero mean and unit variance). The reported estimates can thus be interpreted as the current account effect of an increase of one SD in each of the covariates. The largest effects correspond to the output gap and the oil and gas balance, both considered as transitory. In particular, a one SD increase in the output gap is associated to a reduction of 0.57 SDs in the current account. The fiscal balance and ULCs also present large effects on the current account.

4.1 Current account decompositions

In this subsection, we consider the following decomposition of the current account:

where \({\hat{\beta }}_{i,C} x_{it,C}\) is the so-called cyclical or transitory component of the current account and \({\hat{\beta }}_{i,S} x_{it,S}+ {\hat{\eta }}_i\) refers to the permanent or structural component. To be more concrete, the cyclical factors included in \(x_{it,C}\) are the output gap, the oil and gas balance, oil prices, and the VIX index. On the other hand, in addition to the country-specific intercept \({\hat{\eta }}_i\), the structural factors are those included in the vector \(x_{it,S}\), namely the institutional environment, private credit, the fiscal balance, the dependency ratio, expected growth, the interest rate, and ULCs. Finally, the estimated residuals \({\hat{\epsilon }}_{it}\) as well as the country-specific slopes \({\hat{\beta }}_{i,S}\) and \({\hat{\beta }}_{i,C}\) are taken from column (2) in Table 2 for Spain.

Figure 3 plots the current account decomposition in Eq. (2) for Spain over the 1995–2015 period. We draw two main conclusions from the upper panel. On the one hand, although structural determinants played a non-negligible role in driving current account dynamics in the second half of the nineties, most of the external deficit accumulated over the expansionary years 2000–2007 can be attributed to cyclical factors, namely output gap, oil balance and financial cycle. To be more concrete, around 80% of the current account deficit in 2007 can be explained by those cyclical determinants. On the other hand, the economic recession after the global financial crisis together with the oil balance contributed to the post-2008 adjustment as the cyclical component of the current account was reduced from \(-\,7.1\) pp of GDP in 2008 to \(-\,1.3\) pp in 2015; however, structural factors also played a significant role: their contribution went from negative (\(-\,1.4\) pp) in 2008 to positive (\(+\) 2.7 pp) in 2015. Finally, it is worth highlighting the negligible role of the unexplained component (residual) in most years, which facilitates the identification of the contributions from each factor; this is in sharp contrast to the standard EBA approach under homogeneity in which residuals were relatively large for the case of Spain.Footnote 5

The bottom panel of Fig. 3 plots the contributions from each of the variables included in the analysis.Footnote 6 In the years that immediately preceded the 2000s, the relatively low interest rate induced an expansion in external demand that, coupled with the perceived high institutional quality of the country, was partially responsible for the deterioration of the external balance. Yet, starting from 2001, the negative impact on the current account of these structural factors was crucially complemented by the effect of the positive output gap and the negative oil balance, which strongly fostered external borrowing and ended up being the key drivers of the Spanish current account deficit accumulated up to 2007. To be more concrete, their contributions to the external deficit reached \(-\,6.8\) pp in the case of the oil balance and \(-\,2.3\) pp in the case of the output gap. After the global financial crisis, these two contributions were reverted, while the output gap contributed positively to the current account (\(+\,1.6\) pp) the negative contribution of the oil balance was reduced from \(-\,6.8\) pp to \(-\,4.0\) pp. Finally, it is worth emphasizing the role of the structural adjustment of the fiscal deficit, whose contribution was negative in 2007 (\(-\,1.0\) pp) but positive in 2015 (\(+\,1.6\) pp).

Current account decomposition. Notes. The upper panel plots the cyclical and structural components of the Spanish current account together with the residual term identified from Eq. (2). The bottom panel plots the detailed decomposition with the contribution of each of the regressors included in the analysis (oil balance also includes oil prices)

In order to better gauge the contribution of each factor to the current account adjustment over the 2008–2015 period, we consider the same type of decomposition but in accumulated changes rather than levels.

where \({\tilde{\Delta }}\) refers to the operator that accumulates changes between 2008 and t.

The left panel of Fig. 4 confirms that more than 90% of the explained accumulated deterioration in the Spanish current account in 2007 was due to cyclical factors, in particular to the positive output gap (almost 40%) and to the negative oil balance (more than 50%). The remaining 10% of the overall accumulated deterioration can be related to factors of a more structural nature, such as a relatively high unit labour cost, a low interest rate, and the perceived high institutional quality of the Spanish economy.

Accumulated current account deterioration for Spain. Notes. The left panel plots the cyclical and structural components of the Spanish current account 1995–2007 deterioration together with the accumulated residual term identified from Eq. (3). The right panel plots the detailed decomposition with the contribution of each of the regressors included in the analysis (oil balance also includes oil prices)

Figure 5 shows the same decomposition for the adjustment period that started in 2008. As illustrated in the left panel, around 60% of the overall correction of the Spanish external deficit can be explained by transitory factors.

Accumulated current account adjustment for Spain. Notes. The left panel plots the cyclical and structural components of the Spanish current account 2008–2015 adjustment together with the accumulated residual term identified from Eq. (3). The right panel plots the detailed decomposition with the contribution of each of the regressors included in the analysis (oil balance also includes oil prices)

The remaining 40% of the adjustment can be attributed to other factors of a more permanent nature. In particular, the structural adjustment of the fiscal deficit, the ageing of the population, the lower interest rates, and the lower growth expectations can account for 65%, 23%, 22%, and 15%, respectively, out of the remaining 40% of the overall correction (see right panel of Fig. 5).

A reduction in the fiscal deficit of the public sector contributes directly to the correction of the current account deficit, provided it is not accompanied by an opposite adjustment by the private sector (i.e. Ricardian equivalence does not hold as implied by our estimates). Between 2008 and 2015, the structural component of the fiscal deficit in Spain relative to other countries has been corrected by 2.0 pp, which explains its contribution to the current account adjustment.

According to the economic theory, retirees typically draw down their savings so that higher old-age dependency ratios are typically associated with more negative current accounts. However, the Spanish dependency ratio relative to other countries has decreased by 2 pp from 2008 to 2015, which explains the positive contribution to the current account adjustment.

The effect of long-term interest rates is ambiguous ex ante. On the one hand, lower interest rates can reduce financing costs and thus allow companies to compete internationally in better conditions and gain share in export markets; on the other hand, the expansionary effect of lower interest rates can contribute to a deterioration of the current account. According to our estimates, the evolution of interest rates has contributed positively to the external deficit adjustment via the contractionary effect of the relative increase of the Spanish relative interest rates from 2008 to 2015.

Likewise, lower expectations of future growth lead to lower investment rates (due to the lower expected returns) and more positive current accounts. The expected GDP growth of the Spanish economy relative to the rest of the world has been revised downwards by around 1 pp from 2008 to 2015, which has contributed to the improvement of the current account balance.

5 Delving deeper into current account components: the trade and the investment income balance

Having studied the adjustment of the overall current account balance in the previous section, we next decompose its evolution into the main sub-balances in order to delve deeper into the drivers of the adjustment. Figure 6 shows the decomposition of the Spanish current account balance, as a share of GDP, into the balance of trade (recording net exports of goods and services), the investment income balance (capturing the income received by Spanish residents on their foreign assets minus the payments made on their stock of external liabilities), and the residual balance (reflecting net labour income received from abroad).

Trade and investment income balance. Notes. This plot shows the decomposition of the Spanish current account balance into the balance of trade (recording net exports of goods and services), the investment income balance (capturing the income received by Spanish residents on their foreign assets minus the payments made on their stock of external liabilities), and the residual balance (reflecting net labour income received from abroad)

Changes in both the trade and the investment income balance contributed significantly to the deterioration and the subsequent adjustment of the Spanish current account, while fluctuations in net labour income as reflected in the residual balance played a negligible role. In particular, out of the 11.6 pp. improvement in the Spanish current account between 2007 and 2016, 8.9 pp. were due to a consolidation in the trade balance and 2.5 pp. were explained by the improvement in the investment income balance, while only 0.2 pp. can be related to the residual balance.

In order to investigate further the factors that lead to the consolidation of the main sub-balances, in this section we carry out regressions of the Spanish trade and investment income balance on their fundamental determinants, with the aim of isolating the contribution of cyclical and more structural factors to the overall consolidation.

5.1 The trade balance

Our analysis of the trade balance makes use of the same regression specification employed for the current account in Sect. 4, as we found that that empirical model approximates well the dynamics of the trade balance. Regression results, shown in Table 4 in “Appendix”, are also similar to those obtained for current account regressions, with all the coefficients exhibiting the expected sign. Among the main differences with respect to current account regressions are the lower contribution of expected growth and the lack of significance of ULC and political risk.

Moreover, the credit-to-GDP share was found not to be a significant determinant of the trade balance and the coefficient of the VIX was estimated to be very close to zero, which confirms that the impact on the current account of these financial factors is mostly going through the investment income balance, as the analysis carried out in the next section confirms. All in all, the factors that were responsible for the post-crisis adjustment of the Spanish trade balance were those that also explained most of the overall current account consolidation: among cyclical factors, the negative output gap and the fall in oil prices, and, among more structural determinants, the fiscal consolidation and demographic shifts.

5.2 The investment income balance

Our analysis of the investment income balance started, as for the other regressions, from the EBA current account specification. Yet we found that many of the regressors included in that empirical model do not work well to explain the behaviour of investment income alone, as this is more likely influenced by financial and other specific factors, which may play a secondary role in explaining the evolution of the aggregate current account balance.Footnote 7 For this reason, among the cyclical regressors used in the EBA specification, we kept those defining the real and financial cycle, namely the output gap and the VIX, the latter expressed as deviations from its historical average, and dropped the oil balance, which, according to economic theory, should be more related to the trade component of the current account. As concerns more structural determinants, we kept those that were found to be significant, namely private credit to GDP and the dependency ratio. We also tried to select additional structural factors based on a preliminary accounting decomposition of the financial flows that determine the investment income balance. The left panel of Fig. 7 decomposes the variations in the investment balance into those due to the net payments received on the stock of equity (FDI and portfolio equity) and those due to the net payments received on debt assets. Although in some periods, such as the early 2000 or the first years of the crisis, payments on equity played a relevant role, net income received from debt assets was responsible for the bulk of the fluctuations in the investment income balance in the years that lead to the crisis as well as after 2013. The right panel of Fig. 7 further decomposes payments into those made to international investors and those received from abroad. In periods in which debt payments dominated the evolution of the investment balance, what determined fluctuations in the investment income were changes in what Spain payed to international investors for its stock of external debt, rather than what it received on its external assets.

Accounting decomposition of the investment income balance. Notes. The left panel shows changes in the investment balance distinguishing by net payments received on the stock of equity (FDI and portfolio equity) and net payments received on debt assets. The right panel further decomposes payments into those made to international investors and those received from abroad

These findings indicate that, among structural factors, those that mostly influenced the dynamics of investment income were those linked to the evolution of the Spanish stock of external debt and its rate of return. In this sense, private credit, which in the Spanish case ended up being converted in debt instruments, might have likely been a relevant determinant of the stock of external debt. Other factors that might have affected the profitability of the stock of external debt of the Spanish economy are variations in the short-term nominal interest rate (which we include in the regressions expressed relative to an aggregate of Spain’s main debtor countries) and the share of external debt that is held by the public sector, which, being considered a safer counterpart with respect to the private sector, may lower the implicit rentability of external debt. We complement the specification with two standard determinants of the investment income balance, the lagged stock of net foreign assets as a share of GDP, and fluctuations in the nominal exchange rate with respect to the dollar, interacted with an index of financial liberalization. The time span is 1993–2015 due to data availability.Footnote 8 Table 3 shows the results. As for current account regressions, our baseline estimation features OLS with robust standard errors. As shown in the second column, all results are robust to GLS estimation. Taking into account model uncertainty does not qualitatively affect the main results.

All coefficients display the expected sign. Among cyclical factors, a positive output gap with respect to the rest of the world increases the dividends payed to foreign investors by Spanish firms, with a negative impact on investment income. Consistently with the results of current account regressions, the investment income balance tends to improve in periods of global financial turmoil. This could be due either to a reduction in the availability of financing from abroad in period of crisis or to the role of safe-haven currency of the euro, which tends to reduce the rentability of external debt in periods of global turmoil. As concerns more structural factors, an increase in private credit tends to lead to an accumulation of external debt, which, in turn, worsens the investment income balance. A higher dependency ratio has the same effect as older cohorts tend to reduce their savings. A higher share of external debt held by the public administration, which tends to be regarded as a safer counterpart with respect to the private sector, reduces its implicit rate of return implying lower payments to foreign investors with a positive impact on the investment income balance. Increases in the Spanish nominal short-term interest rate, on the other hand, raise the return of external debt and the payments made to foreign investors, thereby reducing net investment income. Finally, the impact of net foreign assets and nominal exchange rate fluctuations is found not to be significant, but we keep these variables as controls as they exhibit the expected sign. Overall, the regression leaves only a negligible part of fluctuations in the investment income balance unexplained, which allows a meaningful decomposition of the adjustment into cyclical and more structural factors.

Figure 8 shows a level decomposition of the investment income balance into cyclical components—the economic cycle, represented by the output gap, and the global financial cycle, reflected in the VIX—more structural determinants, and the regression residual (see Eq. 2). The decomposition suggests that the deterioration of the investment income balance that took place between 2005 and 2008 was mostly determined by structural factors, while the correction observed after the crisis was related more to cyclical determinants.

Level decomposition of the investment income balance. Notes. This figure plots the cyclical (proxied by the output gap—economic—and the VIX index—financial—) and structural components of the Spanish investment income balance together with the residual term identified from estimates in Table 3

A look at the decomposition of the accumulated investment income balance deterioration into the parts due, respectively, to cyclical and structural factors confirms this finding. The economic and the financial cycle explains only 18% of the deterioration that took place between 2005 and 2008 (Fig. 9, left panel). In particular, as shown in the right panel of the same figure, the main driver of the worsening of the investment income balance was the expansion of private credit, which translated into a higher stock of external debt.

Accumulated deterioration and correction of the Spanish income balance. Notes. This figure plots the detailed decomposition of the Spanish income balance with the contribution of each of the regressors included in Table 3. The left panel refers to accumulated deterioration over the expansion years 2005–2008, while the right panel refers to the post–2008 accumulated adjustment

The accumulated income balance correction that started after the crisis was due more to cyclical factors (28%), especially to the negative output gap (34%). Still, in the most recent years structural determinants gained importance and ended up explaining a considerable part (almost 60%) of the accumulated correction in 2015. Two of them played a particularly important role. The share of external debt issued by the public administration increased, which lowered the implicit rentability of Spanish external liabilities. Moreover, the gradual contraction of private credit tended to reduce the stock of external debt, thereby diminishing payments to foreign investors.

6 A note on the recovery period

In order to study the dynamics of the Spanish current account during the recovery, in this section we extend the decompositions presented in Sects. 4.1 and 5.2 to cover also the period 2016–2018. We use an extended database covering the same variables described in Sects. 3 and 5.2. The source of these variables is either the new vintage of the EBA database or the same source specified in the data sections above.

Figure 10 shows the extended decomposition of the current account adjustment. Notice, first, that the decomposition based on the coefficients estimated in Table 2 fits less precisely the observed correction in the Spanish external balance with respect to the same exercise shown in Sect. 4.1, which is due to the fact that some variables were revised. Yet, it should be noted that the new decomposition still explains almost all the observed adjustment, as the residual is still negligible. Results also unveil that, as the negative output gap gradually closed and oil prices tended to increase back in more recent years, the accumulated adjustment explained by cyclical factors shrunk further, reaching 50% in 2018. Among the structural factors responsible for the correction, the fiscal consolidation increased its relevance, getting to explain roughly 70% of the structural adjustment in 2018, while the impact of relative interest rate got muted.

Accumulated correction of the Spanish current account: extension to 2018. Notes. The left panel plots the cyclical and structural components of the Spanish current account 2008–2018 adjustment together with the accumulated residual term identified from Eq. (3). The right panel plots the detailed decomposition with the contribution of each of the regressors included in the analysis (oil balance also includes oil prices)

Figure 11 shows the extended decomposition of the investment income balance. Also in this case cyclical factors saw their contribution reduced in more recent years, although they were still responsible for 38% of the adjustment in 2017. As concerns structural determinants, the share of debt issued by the Spanish public administration kept being an important driver of the accumulated correction. The reduction in private credit (considered in the model in its lagged version), on the other hand, was contributing to the adjustment only until 2017. For 2018, our regression model for the investment income balance delivers a bad fit. We argue that this is due to the fact that the expansion of private credit observed in 2017 (which enters the 2018 regression) might have mostly materialized in the form of domestic credit, which did not contribute to drive down the income balance in 2018.

Accumulated correction of the Spanish investment income balance: extension to 2018. Notes. This figure plots the detailed decomposition of the adjustment in the Spanish investment income balance over the period 2008–2018 with the contribution of each of the regressors included in Table 3

7 Concluding remarks

The current account balance of the Spanish economy improved by 11.6 pp. since the onset of the crisis, from a deficit of \(-\,10\%\) of GDP at the end of 2007 to a surplus of \(+\,1.9\%\) in 2017. In this paper, we assess to what extent this adjustment was due to cyclical factors (e.g. output gap) or more structural determinants (e.g. demographics). For that purpose, we consider EBA-inspired panel regressions in which country-specific slopes and intercepts are allowed.

Our empirical results indicate that around half of the current account adjustment can be explained by the economic cycle and the fall in oil prices. Other factors contributing to the correction of the external balance include most notably the adjustment in public finances, population ageing, lower growth expectations and the gains in competitiveness of recent years, which can all be considered as more structural determinants. Turning to the investment income balance, the greater share of government debt and the correction in the credit-to-GDP ratio have contributed to its structural adjustment.

Notes

Balta and Delgado (2009) find that the degree of home bias in consumption differs significantly among EU countries, and that it has not changed much following the creation of the EMU. Mika (2017) shows that relevant differences exist in the trade home bias of European economies. Noton (2015) reaches similar conclusions for the car market.

This treatment does not apply to two regressors without cross-country variation in the same year, namely oil prices and the VIX index.

Figure 12 in “Appendix” shows the decomposition for other countries.

The contribution of each factor to the current account balance refers to the relative coefficient in column (2) of Table 2 multiplied by the value of the variable in a specific year. Notice that the contribution of a certain factor to the external balance may be positive (negative) even when the observed current account displays a negative (positive) sign. Figure 13 in “Appendix” shows the decomposition for other countries.

For instance, variables such as the fiscal balance, unit labour costs, and institutional quality turn out not to be significant determinants of the investment income balance.

Short-term nominal interest rates are from the IMF IFS. The Spanish interest rate is expressed relative to a simple average of Spain’s main debtors (France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, UK, US) based on total portfolio investment debt assets from the IMF Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey. Data on external debt held by the public sector are from the Bank of Spain. NFA/GDP and the Chinn and Ito index of financial globalization are from the EBA dataset, while the nominal exchange rate vis-à-vis the US dollar are from the IMF IFS.

References

Abbas A, Bouhga-Hagbe J, Fatás A, Mauro P, Velloso R (2011) Fiscal policy an the current account. IMF Econ Rev 59(4):603–629

Alfaro L, K-Ozcan S, Volosovych V (2005) Why doesn’t capital flow from rich to poor countries? An empirical investigation. NBER working paper 11901

Atoyan R Manning J, Rahman J (2013) Rebalancing: evidence from current account adjustment in Europe. IMF WP 13/74

Balta N, Delgado J (2009) Home bias and market integration in the EU. CESifo Economic Studies

Cheung C, Furceri D, Rusticelli E (2010) Structural and cyclical factors behind current-account balances. OECD working paper 31

Chinn M, Ito I (2007) Current account balances, financial development and institutions: assaying the world savings glut. J Int Money Finance 23(2):546–569

Chinn M, Prasad E (2000) Medium-term determinants of current accounts in industrial and developing countries: an empirical exploration. NBER working paper 7581

Christiansen L, Prati A, Ricci L, Tressel T (2010) External balance in low-income countries. NBER international seminar on macroeconomics

Desbordes R, Koop G, Vicard V (2017) Determinants of the current account: Bayesian model averaging and panel data poolability. Mimeo

ECB (2014) To what extent has the current account adjustment in the stressed Euro Area countries been cyclical or structural? ECB Montly Bulletin

European Commission (2014) The cyclical component of current account balances. European Economic Forecast, Winter

IMF (2013) External Balance Assessment (EBA) Methodology: Technical Background. IMF WP 13/272

Lane P, Milesi-Ferretti G (2002) Long-term capital movements. NBER Macroecon Annu 16:73–116

Medina L, Prat J, Thomas A (2010) Current account balance estimates for emerging market economies. IMF WP 10/43

Mika A (2017) Home sweet home: the home bias in trade in the European Union. ECB working paper 2046

Moral-Benito E (2015) Model averaging in economics: an overview. J Econ Surv 29:46–75

Noton C (2015) On the size of home bias. Appl Econ 47:123–128

Ollivaud P, Schwellnus C (2013) The post-crisis narrowing of international imbalances. Cyclical or durable? OECD working paper 1062

Pesaran H, Smith R (1995) Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. J Econom 68:79–113

Pesaran H, Yamagata T (2008) Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. J Econom 142:50–93

Prais S, Winsten C (1954) Trend estimators and serial correlation. Cowles commission discussion paper no. 383

Sastre T, Viani F (2014) Countries’ safety and competitiveness, and the estimation of current account misalignments. Bank of Spain working paper 1401

Swamy P (1970) Efficient inference in a random coefficient regression model. Econometrica 38:311–323

Tressel T, Wang S (2014) Rebalancing in the Euro Area and cyclicality of current account adjustment. IMF WP 14/130

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This paper does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We would like to thank the editor, an anonymous referee, Pol Antrás and seminar participants at the IMF, Banco de España, and Banque de France for comments and suggestions.

Additional results

Additional results

See Table 4 and Figs. 12 and 13.

Current account decomposition for selected countries. Notes. This figure plots the cyclical and structural components of the current account together with the residual term identified from Eq. (2) for a sample of countries

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delgado-Téllez, M., Moral-Benito, E. & Viani, F. An anatomy of the Spanish current account adjustment: the role of permanent and transitory factors. SERIEs 11, 501–529 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-020-00220-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-020-00220-6