Abstract

We study how taxable income responds to changes in marginal tax rates, using as a main source of identifying variation three large reforms to the Spanish personal income tax implemented in the period 1999–2014. The most reliable estimates of the elasticity of taxable income (ETI) with respect to the net-of-tax rate for this period are between 0.45 and 0.64. The ETI is about three times larger for self-employed taxpayers than for employees and larger for business income than for labor and capital income. The elasticity of broad income is smaller, between 0.10 and 0.24, while the elasticity of some tax deductions such as the one for private pension contributions exceeds one. Our estimates are similar across a variety of estimation methods and sample restrictions and also robust to potential biases created by mean reversion and heterogeneous income trends.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The impact of personal income taxes on the economic decisions of individuals is a key empirical question with important implications for the optimal design of tax policy. Not surprisingly, the modern public finance literature has devoted significant efforts to study behavioral responses to changes in taxes on reported taxable income, as reviewed by (Saez et al. 2012). Most of this work focuses on the elasticity of taxable income (ETI), which captures a broad set of real and reporting behavioral responses to taxation. Indeed, reported taxable income reflects not only individuals’ decisions on hours worked, but also work effort and career choices as well as the results of investment and entrepreneurship activities. Besides these real responses, the ETI also captures tax evasion and avoidance decisions of individuals to reduce their tax bill.

In this paper, we estimate the elasticity of taxable income in Spain, an interesting country to study because during the last two decades it has implemented several major personal income tax reforms, plus a variety of smaller legislative changes, including the ability of regional governments to modify the tax schedule. Due to data availability, we focus on the reforms implemented in the period 1999–2014, which provide useful variation to identify the ETI. We consider all legislative changes in the personal income tax, although identification mainly comes from three major reforms. In particular, the 2003 reform lowered the top marginal tax rate (45–43%) and also reduced the marginal rate for the bottom bracket (18–15%). The 2007 reform was an overhaul of the income tax system, turning the standard personal deduction into a tax credit, which increased the progressivity of the tax. It also modified the definition of tax bases, shifting a substantial part of capital income from the “general” to the “savings” tax base and thereby lowering the marginal rate on capital income. Finally, the 2012 reform, introduced in the middle of a severe recession, increased tax rates across the board, pushing the top marginal rate up to 52% (further increased to 56% in some regions, like Andalusia and Catalonia).

The empirical literature on the ETI has stressed two challenges that could prevent obtaining consistent estimates of this parameter: mean reversion and heterogeneous income trends. Mean reversion is due to transitory shocks to income. When taxpayers receive a transitory income shock in a given year, they tend to revert to their permanent income in subsequent years. This makes it difficult to disentangle changes in reported income due to mean reversion from changes induced by tax reforms. Moreover, the potential bias due to mean reversion has opposite signs for tax cuts and tax increases. The impact of mean reversion is particularly acute in the top and bottom tails of the income distribution, affecting taxpayers with low and high permanent income, who are precisely the groups often targeted by tax reforms.

Heterogeneous income trends across groups of taxpayers differently affected by tax reforms are problematic for similar reasons. Much of the discussion in the literature has centered around the increase in income inequality in the USA in the 1980s (documented by Piketty and Saez 2003), because many papers in this literature evaluate the reduction in the top marginal rate in the 1986 Tax Reform Act. In that setting, it is hard to disentangle whether increases in taxable income by top earners are caused by the tax reform or by the underlying trend toward higher inequality. In the case of Spain, the existence of secular income trends seems less problematic for the estimation of the ETI, as there has been no comparable increase in income inequality over the period under study. However, the asymmetric impact of the Great Recession across groups of taxpayers could also create challenges for identification.

In the empirical analysis, we use an administrative panel dataset of income tax returns compiled by the Instituto de Estudios Fiscales (IEF) with information provided by the Spanish Tax Agency (AEAT). The panel is a random stratified sample with 8.1 million observations over the period 1999–2014 (about 3% of each year’s income tax returns). It contains detailed information on the main components of each income source (labor, capital and self-employment), income-related deductions, the legal tax bases, details on a broad range of tax credits and the overall tax liability for each taxpayer. We use this information to construct a stable definition of taxable income over time. This homogenization is necessary to provide consistent estimates of the ETI for a long period such as 1999–2014 during which significant tax base changes were introduced (e.g., 2007 reform). Since the marginal tax rate (MTR) is not contained in the data, we construct our own tax calculator (in the spirit of the NBER’s TAXSIM for the USA) to calculate the MTR for each taxpayer, and also to build the predicted tax rate instruments described below. We calculate the MTR as a weighted average of the MTR applicable to each income source (labor, financial capital, real estate capital, business income and capital gains).

We use various panel-based two-stage least squares (2SLS) diff-in-diff estimators to obtain consistent estimates of the ETI. The baseline instrument is the predicted change in the net-of-tax rate, defined assuming that income stays constant (in real terms) between a pair of years. This instrument has been used extensively in the literature dating back to Gruber and Saez (2002). Identification comes from heterogeneous changes in the personal income tax schedule across groups of taxpayers due to tax reforms. In all regressions, we control for socio-demographic characteristics of taxpayers (e.g., age, gender, geographic location and indicators for joint filing, children and old-age dependents) that proxy for their permanent income. The presence of mean reversion and heterogeneous income trends in the data motivates the inclusion of nonlinear functions of base-year income, aiming to resolve the potential biases introduced in the estimates. As we discuss in more detail below, we also use state-of-the-art estimation methods proposed by Kleven and Schultz (2014) and Weber (2014) to deal with these identification challenges.

We begin the empirical analysis by examining the existence of mean reversion and heterogeneous income trends in Spain over the 1999–2014 period. Mean reversion is present at the bottom and top tails of the income distribution, which makes it essential to account for mean reversion in the regression analysis. Regarding changes in the income distribution, we show that top income shares have been relatively stable in Spain. This suggests that the existence of secular income trends across groups of taxpayers differentially affected by tax reforms is not a first-order concern in this context.

Our first set of estimates corresponds to an unbalanced panel of taxpayers for the entire period 1999–2014. We obtain estimates of the ETI around 0.35 using the Gruber and Saez (2002)’s estimation method, 0.54 using Kleven and Schultz (2014)’s method and 0.64 using Weber (2014)’s method. This response is robust to the inclusion of nonlinear controls of base-year income in alternative specifications to deal with mean reversion. We undertake several sensitivity tests showing that these estimates are robust to the consideration of alternative base-year income thresholds commonly used in the literature, the examination of permanent taxpayers (balanced panel), the inclusion of pensioners or the exclusion of taxpayers that change their regional fiscal residence during the period of analysis. These baseline ETI estimates are comparable to the “consensus” estimates obtained for the USA (Gruber and Saez 2002; Weber 2014) and other European countries such as Germany (Doerrenberg et al. 2017), but higher than those obtained for Denmark (Kleven and Schultz 2014).

In addition to the average estimates of the ETI, we analyze heterogeneous responses across groups of taxpayers and sources of income. The results on the anatomy of the response are in line with the predictions from the literature. As expected, stronger responses are documented for groups of taxpayers with higher ability to respond. In particular, self-employed taxpayers have a higher ETI than wage employees, while real estate capital income and business income respond more strongly than labor income. The elasticity of broad income (EBI) is between 0.10 and 0.24, substantially lower than the ETI, indicating that deductions play a significant role in taxpayers’ responses. Indeed, we find large responses on the tax deductions margin, especially private pension contributions. Nevertheless, the EBI is relevant in quantitative terms, particularly for self-employed taxpayers, suggesting that there may be real labor supply responses to taxation or evasion behavior that go through reported broad income.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews the large literature on the ETI, including earlier estimates for Spain. Section 3 describes the Spanish personal income tax and the main tax reforms in the period 1999–2014 and also describes the administrative panel dataset used in the empirical analysis. Section 4 provides a simple conceptual framework and discusses our estimation strategy to obtain consistent estimates of the ETI. Section 5 reports the main empirical results and the sensitivity analysis. Section 6 concludes.

2 Relation to the existing literature on the ETI

A large body of research has attempted to estimate the elasticity of taxable income. Although the most influential works focus on the US personal income tax, there are estimates available for an increasing number of advanced economies. As a result of this body of research, meta-analyses of the ETI estimates for a variety of countries have been conducted by Neisser (2017) and Klemm et al. (2018).

In one of the seminal papers in this literature, Feldstein (1995) used a sample of US income tax returns from 1985 and 1988 to study responses to the 1986 Tax Reform Act (TRA). He estimated a very large elasticity, between 1 and 3, which would put the USA on the wrong side of the Laffer curve. Later studies, using an extended dataset for the period 1979–1990 in the USA and more sophisticated regression techniques, revised these estimates downward to about 0.4 (Auten and Carroll 1999; Gruber and Saez 2002). These studies take into account two econometric challenges largely ignored in Feldstein (1995): a trend toward higher income inequality that was unrelated to tax reforms and the existence of substantial mean reversion in taxable income over time. This literature has been extensively summarized by Saez et al. (2012), concluding that the “best available estimates [of the ETI in the US] range from 0.12 to 0.40” (p. 42). The literature also examined the anatomy of the response in the USA, which results in small elasticities of broad income (EBI), around 0.1, indicating that most of the taxpayers’ reaction is through itemization rather than real or reporting responses in gross income. Furthermore, the empirical literature documents a much stronger response of taxpayers with a broader scope to react (e.g., self-employed vs. wage employees) and larger reactions in specific sources of income such as capital and business income.

Regarding the interpretation of the ETI, Feldstein (1999) established the conditions under which the ETI is a sufficient statistic to evaluate the efficiency cost of the income tax. The argument rests on the idea that responses to income taxation include behaviors like evasion and avoidance, not only labor supply responses. Focusing on taxable income as the outcome variable allows us to estimate the overall response, even if some of these components are hard to measure directly. Chetty (2009) qualified Feldstein’s argument pointing out that, if evasion and avoidance behaviors lead to transfer costs to other agents, the estimated ETI is no longer a sufficient statistic. Doerrenberg et al. (2017) presented a similar theoretical framework to examine the role of tax deductions and provided evidence that reported deductions are highly responsive to tax changes in Germany. Finally, Gillitzer and Slemrod (2016) discussed the conditions under which Feldstein’s original result would still hold, restating the argument in terms of fiscal externalities. This research stressed the relevance of examining the different channels of taxpayers’ response to tax changes, such as the use of tax deductions or the anatomy of the response inferred from gross income changes.

In an early critique of this literature, Slemrod (1992, 1998) pointed out that the ETI is not a stable parameter (neither over time nor across countries) and stressed the idea that government policy can have an effect on the ETI. For example, wide availability of tax deductions and exemptions is likely to lead to a larger elasticity of taxable income, all else equal. Similar arguments are made by Kopczuk (2005), who also warns about focusing only on marginal tax rate changes, when most reforms simultaneously modify the definition of the tax base. Taking these insights together, the literature highlighted the need to provide estimates on both the anatomy and the heterogeneity of the response of taxpayers, keeping a definition of taxable income stable over the period under analysis.

Some recent work has challenged the “consensus” empirical strategies from Saez et al. (2012), proposing alternative estimation techniques. Weber (2014) shows that the Gruber–Saez instrument is endogenous because it is correlated with recent income shocks. She proposes using further lags of taxable income to construct the predicted net-of-tax rate instrument, as these lags are less correlated with current income shocks and provide more credible identification. Applying her method to the same dataset used by Gruber and Saez (2002), she estimates a larger elasticity in the range between 0.68 and 0.86. This elasticity is similar in order of magnitude to the baseline ETI estimate for Germany obtained following Weber’s proposal in Doerrenberg et al. (2017) which is in the range of 0.54 to 0.68. In contrast, the estimate of the EBI (0.47) reported in Weber (2014) is larger than the EBI estimates obtained in Doerrenberg et al. (2017), with estimates between 0.16 and 0.28. Using time-series methods and a “narrative” approach to describe postwar tax reforms in the USA, Mertens and Olea (2018) estimate a substantially larger ETI of around 1.2, with an even larger elasticity for high income earners and a positive and significant elasticity elsewhere in the income distribution.

In another influential study, Kleven and Schultz (2014) apply a refinement of the Gruber–Saez estimation strategy, adding an instrument for virtual income to separately estimate income effects. They analyze a series of income tax reforms in Denmark, arguing that estimating the ETI using a longer period and the variation of multiple tax reforms is a more reliable empirical strategy to identify causal effects of taxes than the usual one-reform analysis. Additionally, the authors stress the suitability of examining economies less affected by the unusual empirical challenges to identify the ETI such as Denmark where income distribution has been stable over time and tax changes affected different parts of the income distribution, reducing the potential bias from mean reversion. They estimate the ETI and EBI for overall income and also separately for labor and capital income, finding consistently small values between 0.05 and 0.2.

2.1 Existing estimates of the ETI for Spain

As noted above, estimates of the ETI are available for most advanced countries and Spain is no exception. However, only a few of the existing studies have been published in peer-reviewed journals (Sanmartín 2007; Sanz-Sanz et al. 2015; Díaz-Caro and Onrubia 2018). Sanmartín (2007) exploits the income tax reforms of 1988 and 1989, which lowered substantially the top marginal rate and allowed married couples to file two individual declarations. Following the empirical strategy proposed by Auten and Carroll (1999), he constructs a predicted tax rate instrument using data for the years 1987 and 1990 and obtains ETI estimates between 0.1 and 0.2. One caveat about these estimates is that the empirical strategy may lead to a downward bias in the ETI estimates when studying a tax cut in the presence of mean reversion.

Both Sanz-Sanz et al. (2015) and Díaz-Caro and Onrubia (2018) exploit the 2007 income tax reform. Sanz-Sanz et al. (2015) estimate the elasticity of gross income (EGI), rather than taxable income, using the standard predicted tax rate instrument. They estimate an EGI between 0.55 and 0.68 (depending on the base-year income controls), which is higher than other estimates of the EGI in the literature. Díaz-Caro and Onrubia (2018) use a stable definition of taxable income before and after the 2007 reform to estimate the ETI. They obtain point estimates between 0.41 and 0.43 and provide estimates for different groups of taxpayers. Notice that focusing the identification on the 2007 tax reform is problematic because the tax base was substantially modified, along with the marginal rate schedule. Moreover, both papers use data only for years 2006 and 2007, in contrast to the standard 3-year interval used in the literature to avoid capturing income-shifting responses that bias estimates. Therefore, these estimates should be interpreted with caution.Footnote 1

Our paper departs from the earlier literature on the ETI in Spain by considering a much longer time period (1999–2014) over which multiple tax reforms took place, including both tax cuts and tax increases. This provides much richer identifying variation, allowing us to obtain more consistent estimates of the ETI. Besides the longer period of analysis, we adopt state-of-the-art methodological approaches to estimate the ETI, simultaneously dealing with the multiple threats to identification. In particular, we present estimates using the Gruber and Saez (2002) 3-year difference estimator as a baseline and compare them to the results obtained with the methods proposed by Kleven and Schultz (2014) and Weber (2014). In addition to this, we present evidence on the responsiveness of tax deductions, following Doerrenberg et al. (2017), and estimate the elasticity for different sources of income, as done by Kleven and Schultz (2014). These estimates are subject to a comprehensive set of sensitivity analysis to show the robustness of the reported ETI estimates for Spain.

3 Institutional background and data

3.1 The Spanish personal income tax

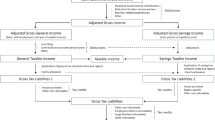

During the period analyzed in this paper, 1999–2014, the Spanish personal income tax (PIT) has been structured in two separate tax bases: a “general” tax base comprising a broad definition of taxable income taxed with a progressive schedule and a “special” tax base comprising specific income sources taxed with a flat-rate schedule. Until 2006, the special tax base included only some types of capital gains. In 2007, it was renamed the “savings” tax base and additional components of capital income were added, as explained in more detail in Sect. 3.2.

Taxable income in the general tax base is computed in several steps. The first step is to sum the gross income from each income source.Footnote 2 Second, the income-related expenditures (required to earn that income) are subtracted from each income source, resulting in the adjusted gross income (AGI). Third, income-specific deductions are subtracted from each AGI to obtain the taxable income for each source.

As an example, taxable labor income results from adding the gross income earned by workers (e.g., wages and salaries, bonus, in-kind payments) and subtracting income-related expenditures, such as payroll taxes for wage employees, and then subtracting income-specific deductions (e.g., the general reduction for labor income). The process is the same for other income sources.Footnote 3 After computing taxable incomes from all sources and adding them up, a set of general deductions is subtracted to obtain the general taxable income, which is taxed with a progressive tax schedule.Footnote 4

The special (savings, since 2007) tax base is taxed at a preferential tax rate, targeted at particular components of capital income.Footnote 5 In the period 1999–2006, the preferential tax rate was applied only to long-term capital gains, while in 2007–2014 special taxable income included capital gains derived from the transmission of assets as well as the main component of financial capital income (i.e., income from interests and dividends). Taxable income in this case results from subtracting the remnant of deductions not applied in the general tax base, as well as allowances for past capital losses.

The application of the progressive tax schedule to the general tax base and the flat rate to the special/savings tax base yields, respectively, the general and the special/savings tax liability. The aggregate tax liability from these two tax bases is further reduced by the application of several tax credits, resulting in the tax due. The most relevant tax credits in quantitative terms are the mortgage interest tax credit for primary dwellings, the tax credit for the birth or adoption of children, the €400 stimulus tax credit in effect in 2008 and 2009 and the refundable maternity tax credit for working mothers with children below 3 years, established in 2003.Footnote 6

The legislative power to rule and reform the personal income tax law has traditionally been assigned to the Spanish parliament, which designs the structure and main features of the tax (often following the initiative of the central government). However, since 1997 regional parliaments have progressively obtained legislative capacity (extended in 2002 and 2010) to introduce changes in the tax schedule for the general base, modifications in the personal and family deductions and also the ability to introduce new tax credits. In spite of the regional dimension of the tax, the PIT is administered at the national level in a unique tax return by the Spanish Tax Agency.Footnote 7

3.2 Tax reforms

The specific definition of the components that determine tax bases as well as the tax rates applied to taxable income have been subject to substantial modifications over time. These changes are due to major reforms of the PIT but also to significant changes passed in the annual Budget Law and measures included in other bills.Footnote 8 The core reforms of the PIT that provide us with useful identifying variation were put into force in 2003, 2007 and 2012 fiscal years. (Note that the fiscal year coincides with the calendar year). We also consider changes in the general tax schedule at the regional level. These regional changes were modest until 2010, when in the context of the European Sovereign Debt Crisis regional parliaments became more active in creating new brackets with higher marginal tax rates for top income earners (see discussion in Online Appendix A). These two sets of changes in the PIT constitute the identifying variation that we use to estimate the elasticity of taxable income for the period 1999–2014.

The 2003 Reform reduced the top marginal tax rate from 48 to 45% (a 6.25% cut) and the lowest marginal rate from 18 to 15% (a 20% cut). The top panels of Fig. 1 depict the changes in the marginal tax rate (MTR, left) and average tax rate (ATR, right) by levels of taxable income. The reform reduced the number of tax brackets (from six to five) and was particularly beneficial for taxpayers with taxable income between €40,460 and €45,000, as they experienced a 16.7% reduction in their marginal tax rate (from 45 to 37%). The tax rate on capital gains was also reduced from 18 to 15%. Besides the lower marginal tax rates, the reform expanded the amounts of the personal and family deductions. The most relevant change in tax credits was the introduction of a new refundable cash credit for working mothers with children below 3 years that could reach €1200 per year. The ex ante revenue impact of this pro-cyclical reform was significant with an estimated permanent tax revenue reduction equivalent to 0.50% of GDP in 2003 (Gil et al. 2019).Footnote 9

Tax reforms. Notes: The top panels depict the income tax schedule on the general tax base before and after the 2003 reform, which reduced the marginal tax rate (MTR) at the bottom and top of the taxable income distribution (top-left panel), leaving the middle brackets almost unaffected and resulting in a reduction in the average tax rate (ATR) for all income levels (top-right panel). The bottom panels depict the tax schedule on the general tax base before and after the 2012 reform, which increased the marginal and average tax rates for all income levels, with a larger increase for higher incomes. We use a log scale for base year in the horizontal axis for comparability with Fig. 3

The 2007 Reform was a significant overhaul that modified both the definition of taxable income in the two tax bases and the overall tax structure. The two most relevant changes were (i) moving most financial capital income from the general to the savings tax base and (ii) converting the personal and family exemptions (with the exception of the deduction for joint filing) into a tax credit from the general tax liability, rather than a deduction from the tax base. Regarding (i), income from interest and dividends went from being taxed at 45% in the general base to being taxed at the 18% flat rate in the savings base (a 60% reduction in the MTR). This implied a dramatic reduction in the marginal tax rate for medium- and high-income taxpayers with substantial financial income. Notice that this modification could also imply lower marginal rates for additional income obtained from other sources such as labor, real estate or business income. The reform also expanded the definition of capital gains taxed under the savings tax base, including all gains from the transmission of assets regardless of the period over which the gain was generated.Footnote 10 Regarding (ii), the new way to calculate tax liability consisted of applied the progressive tax schedule to general taxable income and the personal and family exemption separately, and then subtracting the two resulting amounts. Notice that this change increased the progressivity of the tax schedule, because in the new system all taxpayers with the same personal and family characteristics obtain the same reduction in tax liability, while in the case of a deduction, tax liability decreases in proportion to each taxpayer’s marginal tax rate.

It the 2007 reform, the number of brackets in the progressive tax schedule for the general tax base was reduced from 5 to 4. For example, a small bracket with a 15% rate that applied to incomes up to €4161.6 in 2006 was eliminated and replaced by a larger bracket for incomes up to €17,700 taxed at a 24% rate. The reform also expanded a tax bracket for middle income, reducing the marginal tax rate in the range €26,842.3–€32,360.6 by 32.1% (from 37 to 28%). Similarly, income between €46,810 and €52,360.6 experienced a 21.6% reduction in the marginal tax rate (from 45 to 37%). Finally, the top marginal rate was also reduced by 4.7% (from 45 to 43%). The ex ante revenue impact of this reform is estimated to imply a reduction in permanent tax revenue equivalent to 0.3% of GDP in 2007 (Gil et al. 2019).

The 2012 Reform consisted of a general increase in marginal tax rates for all taxpayers, increasing the progressivity of the tax schedule in both the general and savings tax bases. In 2011, the central government had already introduced two additional brackets with higher marginal tax rates for top income earners: 44% for taxable income between €120,000 and €175,000 and 45% for taxable income above the latter amount. On the same year, some regional governments modified their tax schedules as well, reaching a top marginal rate of 49% in Andalusia and Catalonia. The 2012 reform increased the marginal tax rates for all brackets: by 3.1% for the first, 7.1% for the second, 8.1% for the third, 9.3% for the fourth, 11.4% for the fifth, 13.3% for the sixth and 15.6% for the newly created seventh bracket (for taxable income above €300,000). The pre- and post-reform tax schedules are shown in the bottom panels of Fig. 1. The reform also increased the tax rates on savings income, introducing some progressivity on the savings tax schedule. Savings income up to €6000 was now taxed at 21%, a second bracket up to €24,000 at 25% and any savings income above that at 27%. The ex ante estimated tax revenue impact of this pro-cyclical reform was 0.50% of GDP in 2012 (Gil et al. 2019).

3.3 Data

We use an administrative panel dataset of income tax returns compiled by the Instituto de Estudios Fiscales (Pérez et al. 2018) with information provided by the Spanish Tax Agency (Agencia Estatal de Administración Tributaria, AEAT). This panel contains a random sample of about 3% of all income tax returns filed in Spain in the period 1999–2014.Footnote 11 The sample is stratified by gross income level (ten categories), region (15 autonomous communities and the two autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla) and a binary indicator of the main source of income (whether labor is the main income source or not) based on information from 2003 (the base year). To mitigate panel attrition, going forward and backward in time, taxpayers that drop out from the panel are replaced by new filers in their same income–region–source stratum.

The dataset contains more than 8.1 million tax returns (about 500,000 per year, on average), with a larger sample in the more recent years reflecting the increase in the total number of taxpayers. Each tax return is associated with a sampling weight that represents the inverse of the probability of being selected. Using these weights, the yearly aggregates of the main gross income and tax base and liability magnitudes are representative of the ones reported in the universe of the population (see Onrubia et al. 2011, for more details).

The dataset contains detailed information on the main components of all income sources, income-related deductions of type of income, the rights and effective tax exemption of each deduction, the legal tax bases, disaggregated information on a broad range of tax credits and the overall tax liability. In terms of socio-demographic characteristics, we observe gender, date of birth, province and city of residence. Besides, the information in the tax return data allows us to infer the number of children and dependents that each taxpayer is responsible for. Table 1 reports the share of income due to each income source (left panel) and the share of income received by each category of taxpayer (right panel). About 80% of income reported in the Spanish PIT is labor income, 8.9% capital income, 8.3% business income and 3.9% capital gains. If we classify taxpayers into different categories based on their most important source of income, we observe that wage employees account for 82% of the tax returns analyzed. Self-employed taxpayers represent 7.8% of the sample, although it is worth noting that only two-thirds of these (5.2% of the total) are under the direct estimation regime. The rest of self-employed taxpayers are in the “objective estimation” or agricultural regimes, where the tax liability is determined based on observable features of each business, rather than actual income. For this reason, in the analyses performed below, we will only consider the first group as self-employed.Footnote 12 The remaining 10% of taxpayers are almost equally split into the “saver” and “investor” categories, where the most relevant income sources are capital income or capital gains, respectively.

The marginal tax rate (MTR) is not directly observed in the tax return data. Thus, we use the available information on income and regional location, as well as the main tax base parameters, to calculate the MTR with a self-constructed tax calculator in the spirit of the NBER TAXSIM used in studies about the USA. Building this tax calculator is critical for our empirical strategy, as it is needed to calculate the predicted net-of-tax rate instrumental variable used to identify causal effects.Footnote 13 We calculate the marginal tax rate separately for each income source, following Kleven and Schultz (2014). We first calculate the tax liability for the observed taxable income and then redo the calculation adding €10 to that amount. Then, we divide by 10 the difference between the two tax liabilities, to obtain the marginal tax rate for each income source:

In most of our regression analysis, we estimate the elasticity of taxable income with respect to the net-of-tax marginal rate. Therefore, we need a measure of the “overall” marginal tax rate faced by each taxpayer. To do this, we construct a weighted marginal tax rate on all taxable income, where the weights correspond to the relative importance of each income source in each tax return.Footnote 14 Let the share of income due to source j be denoted by \(s_{it}^{j}\equiv \left( z_{it}^{j}/z_{it}\right) \).Footnote 15 Then, the overall marginal tax rate for taxpayer i in year t is given by:

3.3.1 Sample selection and homogeneous definition of the tax base

We follow the existing literature to apply some sample restrictions to arrive at the estimation sample. First, we exclude taxpayers with negative taxable (or gross) income. This is important because the main outcome variable is defined as the change in log taxable income, which would not be properly defined if income in one of the periods is negative. Since joint filing is only preferable for households in which the second earner has very low income, we consider the tax declaration the unit of analysis. Moreover, we drop year-pair observations where taxpayers change their filing status between the base year (t) and \(t+s\). Further, we exclude pensioners, identified as taxpayers aged 65 and above with positive labor income but zero social security contributions. The reason for excluding pensioners is their main source of income is determined mechanically by public pension rules. Note that our main results are robust to including pensioners in our estimation sample.

Contrary to common practice in the literature (e.g., Gruber and Saez 2002, and followers), we do not exclude observations below a certain threshold of gross income in the base year. Instead, we carefully document and quantify the existence of mean reversion in each period. Then, in the regression analysis, we test different specifications of nonlinear controls for base-year income to find an econometric solution to this potential bias. In a robustness test, we check that our results are not affected by dropping taxpayers with broad income below €5000 or €10,000 in the base year (see Sect. 5 for details).

In line with the rest of the literature, our tax calculator contains a consistent definition of taxable income over time. This constant definition may not match the “legal” definition of taxable income in every year, but this homogenization of the tax base is needed for providing consistent estimates when tax reforms change the tax base (e.g., the 2007 reform). Without this adjustment, the dependent variable would change mechanically every time the legal definition of the tax base changes, leading to biased estimates (Kopczuk 2005; Weber 2014). When homogenizing the tax base over time, we follow the earlier literature in excluding capital gains from the tax base, because its tax treatment and economic nature are quite different from other income sources (see, for instance, the discussion in Saez et al. 2012). We also consider the fact that financial capital income is taxed under different tax bases over this period, as well as the fact that the main component of personal and family deductions is converted into tax credits since 2007.

Data availability allows us to compute for each year the gross and the adjusted gross income for each source of income taxed in the PIT. We also have detailed yearly information on the implementation rules and the amount of both the income-specific and the general deductions that are subtracted from each component of gross income and from the aggregation of these components. In the particular case of homogenizing over time the personal and family tax credits created in 2007, we assume that the base of these tax credits is equivalent to a deduction that reduces the general taxable income as in the period 1999–2006. Taking together data availability and our homogenization assumptions, we can create a homogenous definition of aggregate taxable income in the Spanish PIT over the period 1999–2014.

3.3.2 Summary statistics

Table 2 reports summary statistics for the final sample used in the regression analyses, covering the period 1999–2014. All monetary variables are in real 2012 euros. The sample restrictions described above plus the fact that we take 3-year differences of the data in each period (which means we “lose” 3 years of observations) result in a baseline panel dataset with 4.02 million observations.

Real average gross income in 2012 euros is €36,200, and real average taxable income is €23,392, both with high dispersion and highly skewed to the right (i.e., the median is lower than the average in both cases). The average net-of-tax rate is 0.71, corresponding to a marginal tax rate of 29%. The average change in log real taxable income is \(-\,0.02\), although there is substantial heterogeneity in this variable, which can take large values both positive and negative. The average change in the log net-of-tax rate is also close to zero \((-\,0.01)\), with substantial variation on both sides of its distribution. Finally, the average taxpayer is 46.6-year old, 42% of taxpayers are female and 17 of households file jointly. (In the latter case, the dataset records the gender and age of the primary earner.)

4 Estimation strategy

We follow the previous literature and estimate a model in differences, using the predicted change in the net-of-tax rate as an instrument for the actual change. To address the identification challenges of mean reversion and heterogeneous income trends, we employ a variety of nonlinear controls for base-year income as well as modifications of the baseline instrument that have been proposed in the literature.

4.1 Conceptual framework

Consider the taxable income model used in the literature, which is an extension of the traditional labor supply model. Taxpayers maximize a utility function u(c, z), where c is consumption and z is reported taxable income. This function is increasing in consumption and decreasing in taxable income, because generating income is costly. The budget constraint is given by \(c=z-T(z)\), where \(T(\cdot )\) represents tax liability, which is the result of applying the tax schedule (a potentially nonlinear function) to a given taxable income. Note that this budget constraint may also be written as \(c=(1-\tau )z+y\), where \(\tau \equiv T'(\cdot )\) is the marginal tax rate and \(y\equiv \tau z -T(z)\) is virtual income. The latter can be thought of as the reduction in tax liability that results from the progressivity of the tax schedule, compared to a linear tax system with a tax rate equal to \(\tau \). Graphically, virtual income can be depicted by extending the part of the budget set where the taxpayer is located and finding its intersection with the vertical axis. Given this setup, we can write the optimal choice of taxable income as \(z=z(1-\tau ,y)\).

Following Kleven and Schultz (2014), we write the following log-linear specification:

where \(\mu _i\) is an individual fixed effect that absorbs all time-invariant individual characteristics. We include two sets of controls: \(\mathbf{x }_{i}^{c}\) includes time-invariant characteristics whose effect may change over time (e.g., gender or joint vs. individual filing), and \(\mathbf{x }_{i,t}^{v}\) includes time-varying characteristics assumed to have a stable effect over time (e.g., age, region). The term \(\varepsilon \) can be interpreted as the elasticity of taxable income with respect to the net-of-tax rate, while \(\eta \) is the elasticity with respect to virtual income. Notice that, in this formulation, \(\varepsilon \) is the uncompensated elasticity, because the inclusion of virtual income implies a linearization of the budget set around the optimal income choice.Footnote 16

As is standard in the literature, we estimate a model in differences:

where \(\Delta \ln (z_{i,t}) \equiv \ln \left( \frac{z_{i,t+s}}{z_{i,t}} \right) \), \(\Delta \ln (y_{i,t}) \equiv \ln \left( \frac{y_{i,t+s}}{y_{i,t}} \right) \) and \(\Delta \ln (1-\tau _{i,t}) \equiv \ln \left( \frac{1-\tau _{i,t+s}}{1-\tau _{i,t}} \right) \). After taking differences, the individual fixed effect \(\mu _i\) drops out of the model. Notice that in this specification, each observation consists of two tax returns from different years. With this notation, the base year in each observation is denoted as year t.

4.2 Identification strategy

Estimating Eq. (2) by ordinary least squares (OLS) would result in a biased estimate of the ETI whenever the tax schedule is nonlinear (e.g., features progressivity), because changes in taxable income can mechanically lead to changes in the net-of-tax rate. For example, a positive income shock leads to an increase in the dependent variable and it may also push the taxpayer to a higher marginal rate bracket, thereby reducing the net-of-tax rate. This negative correlation between the dependent variable and the error term creates an endogeneity problem, leading to a severe downward bias on the ETI estimates obtained through OLS estimation of Eq. (2), as shown in panel (a) of Fig. 2.

Graphical analysis (1999–2014). Notes: Each dot in these figures represents the average of the vertical axis variable over bins of the horizontal axis variable, where the each bin contains a similar number of observations. a Represents the OLS relationship between the outcome variable of interest \(\Delta \ln (z)\) and the endogenous covariate \(\Delta \ln (1-\tau )\). b Represents the first-stage relationship between the endogenous covariate \(\Delta \ln (1-\tau )\) and the predicted tax rate instrument \(\Delta \ln (1-\tau ^p)\). c Represents the reduced-form relationship between the outcome variable \(\Delta \ln (z)\) and the instrument \(\Delta \ln (1-\tau ^p)\), where the latter has been computed using one, two and three lags of taxable income. The regression lines depicted are estimated using the same number of observations as in the regressions in columns 1–3 of Table 3, without including any controls or fixed effects

To deal with this endogeneity issue, we follow the instrumental variables strategy first proposed by Gruber and Saez (2002), which has become standard in this literature. They note that a change in the marginal tax rate can be due to a tax reform (mechanical effect) or to taxpayers’ reoptimization (behavioral effect). The goal is to isolate the exogenous variation created by tax reforms, netting out the behavioral response that may have also affected the observed marginal rate. Specifically, Gruber and Saez (2002) compute the marginal tax rate that taxpayers would have faced in period \(t+s\) (where the convention is to use \(s=3\)) if their income had been the same (in real terms) as in the base year, t. In practice, we calculate this predicted net-of-tax rate, \(\tau ^p\) using the following expression:

where the subscript in \(T_{t+s}\) indicates that we calculate the tax liability using the tax schedule of period \(t+s\). We can then easily construct the instrument for the change in the log net-of-tax rate as follows:

Then, the instrument is defined as the (log) change between the marginal tax rate faced in t and the tax rate they would have faced in year \(t+s\) keeping their real income from year t. The first-stage relationship can be written as follows:

As we show below, this instrument yields a very strong first-stage relationship. Therefore, we can safely conclude that the instrument is relevant. However, it is not guaranteed that the exclusion restriction holds if base-year income is a good predictor of future income change, potentially making the instrument invalid. For example, the influential paper by Weber (2014) argues that the instrument may violate the exclusion restriction when taxable income features substantial serial correlation because shocks to \(z_t\) are correlated with shocks to \(z_{t+s}\). We explore the implications of this issue in the following subsection.

In the regressions following the estimation method of Kleven and Schultz (2014), we include virtual income in the regressions to account for income effects. The theoretical definition states that virtual income is equal to the tax liability that would apply to a taxpayer if all her taxable income was taxed at the marginal tax rate, minus her actual tax liability. That is:

Notice that, with a progressive tax schedule, virtual income is by definition nonnegative.

To construct the instrument for the change in log virtual income, we use the predicted marginal tax rate that we calculated to construct the net-of-tax rate instrument. Then, the instrument is given by:Footnote 17

4.2.1 Mean reversion and heterogeneous income trends

The literature has extensively discussed two challenges to the empirical identification of the ETI: mean reversion and heterogeneous income trends unrelated to tax changes (Saez et al. 2012). We discuss them in detail here and describe some potential solutions that have been proposed.

Mean reversion arises because taxpayers with a positive (negative) income shock in year t tend to have, on average, lower (higher) income in year \(t+s\) (\(s=1,2,3...\)) as they return to their permanent income. In our specific context, Fig. 3 plots the change in log taxable income between period t and period \(t+s\) by bins of base-year taxable income, for periods 1999–2006 (left) and 2007–2014 (right). Mean reversion is clearly visible in these graphs: the change in log taxable income is very high for taxpayers with low base-year taxable income and substantially lower than average for those with high base-year taxable income. Notice also that there is no evidence of mean reversion in the middle of the income distribution, i.e., between €10,000 and €50,000, suggesting that the problem is constrained for extreme income observations. Using a log scale in the horizontal axis makes these figures consistent with the log–log specification of Eq. (2).

Mean reversion problem. Notes: Each dot represents the average change in log taxable income for bins of base-year taxable income (in real euros, using a log scale). Observations are grouped into 100 intervals of the horizontal axis with a similar number of observations. Thus, more spaced points indicate that there are fewer taxpayers in a given income range. a Refers to the 1999–2006 period and b refers to the 2007–2014 period. Both figures show the existence of mean reversion in the low and the top tails of the income distribution. Mean reversion is particularly relevant for the second period of analysis (b), especially at the bottom of the distribution but also at the top

In both periods, mean reversion is concentrated at the top and, most dramatically, at the bottom of the distribution. The pattern is significantly more pronounced in the 2007–2014 for two reasons. First, the definition of taxable income is different, as explained in Sect. 3.1: From 2007 onward, the personal exemption is not deducted from taxable income, but rather treated as a tax credit which is subtracted from “gross” tax liability. Thus, taxpayers with low gross income (below the personal exemption) are included in the calculations for 2007–2014 as they have positive taxable income, but they are not included in 1999–2006. Second, the behavioral responses at the top of the distribution have different effects for tax cuts versus tax increases. In the 2003 reform, the top marginal income was reduced, so we expect high earners to increase their taxable income, partly canceling out the mean reversion pattern. Instead, after the 2012 tax increase, we expect high earners to decrease their taxable income, thereby exacerbating the mean reversion pattern in this figure. To sum up, the main implication from the evidence shown in Fig. 3 is that although the mean reversion problem is more relevant for the period 2007–2014 than for 1999–2006, mean reversion should be considered when estimating the ETI for the full period 1999–2014.

Heterogeneous income trends across groups of taxpayers that are differently affected by tax reforms are problematic for the estimation of the ETI, as they may be a confounder when trying to identify the response to tax changes. In the case of the USA, the sustained increase in income inequality in the 1980s complicates the analysis of the 1986 Tax Reform Act. This reform implied a large drop in the top marginal tax rate, so the (relatively) high income growth rate for top earners could be due to both the response to the tax reform and the general increase in income inequality due to secular trends in income of top earners. The US literature has devoted a lot of attention to this issue (see Saez et al. 2012, for a summary). However, in countries where the income distribution has been more stable, this issue would be less relevant. In Fig. 4, we show the evolution of top income shares in Spain throughout the period 1999–2014, using the same panel dataset as in our regression analysis. Specifically, we plot the total gross income earned by taxpayers in the top 0.1, 1 and 5%, where each category includes the smaller ones. There are no significant changes in top shares in this period, suggesting that secular income trends are not a first-order issue when estimating the ETI for Spain.Footnote 18 However, the Great Recession could have created heterogeneous income trends across groups of taxpayers in the middle of the income distribution suggesting the need to consider them in the empirical strategy.

Top income shares, 1999–2014. Notes: This figure shows the evolution of top income shares annually for the period 1999–2014. For each year, we calculate the total amount of gross income earned by taxpayers in the top 0.1, 1 and 5% of the distribution and then compute their share out of total gross income reported by all taxpayers. The data are from tax returns included in the administrative panel dataset compiled by the Instituto de Estudios Fiscales (see Sect. 3.3 for details). To compute the income shares, we elevate each observation included in the sample by the sampling weight reported in the data, which represents the inverse of the probability of being selected. Gross income is defined as the sum of all income components (labor, financial capital income, real estate capital income, business income and other imputed income) taxed in the Spanish personal income tax, excluding capital gains due to their transitory nature

To address the potential bias from mean reversion and heterogeneous income trends, multiple studies have proposed ways to control for log base-year income. For example, beginning with Auten and Carroll (1999), many papers in this literature include log base-year taxable income in a specification similar to (2), while Gruber and Saez (2002) include cubic splines of that variable to allow more flexibility. Weber (2014) addresses the empirical challenges to estimate the ETI using two differentiated strategies. She proposed dealing with mean reversion by constructing the predicted tax rate instrument using further lags of taxable income. Regarding heterogeneous trends in income, she uses splines of log taxable income in periods prior to the base year, following her argument that nonlinear functions of log base-year taxable income may be endogenous. Finally, Kleven and Schultz (2014) apply a refinement of the Gruber–Saez estimation strategy, adding an instrument for virtual income to separately estimate income effects. We report results from multiple variants of these state-of-the-art methodological approaches to estimate the ETI in the next section.

5 Results

We first present our main estimates of the elasticity of taxable income for the period 1999–2014, using the longest panel dataset available in a consistent format. We present results for the three alternative estimation methods described in the previous section: Gruber and Saez (2002), Kleven and Schultz (2014) and Weber (2014). Second, we analyze the heterogeneity of the elasticity by type of taxpayer and by source of income. We then study the anatomy of the response to tax reforms by estimating the elasticity of broad income (EBI) and the responsiveness of several tax deductions, to assess what part of the ETI is due to real, avoidance and evasion responses. In the last subsection, we conduct two additional robustness exercises: First, we exclude taxpayers below a given threshold of base-year taxable income (€5000 and €10,000), a strategy often used in the existing literature to mitigate mean reversion at the bottom of the distribution. Second, we obtain elasticity estimates with alternative time differences, i.e., 1-year and 2-year differences instead of the standard 3-year difference. Finally, we discuss several sensitivity analyses of the baseline estimates: (i) including lagged splines in each estimation method; (ii) estimating the ETI on a balanced panel of taxpayers; (iii) including pensioners in the estimation sample; and (iv) excluding taxpayers who move across regions.

5.1 Main elasticity estimates

The first three columns in Table 3 report the OLS, first-stage, reduced-form estimates for the period 1999–2014 to show how the estimation strategy affects the elasticity estimates. Columns 4–6 show the two-stage least squares (2SLS) for different specifications using the predicted tax rate instrument proposed by Gruber and Saez (2002). All specifications include year and region fixed effects to control for common shocks. To proxy for taxpayers’ permanent income, we also include age, age squared and indicators for gender, joint filing, the presence of children or old-age dependents in the household, and the main source of income. (Note that we include this set of controls in all specifications reported below, unless otherwise noted.) Column 1 reports the results from OLS estimation of (2). The coefficient on \(\Delta \ln (1-\tau )\) is negative, large \((-\,4.230)\) and statistically significant at the 1% level. This is consistent with substantial downward bias, as predicted by theory. Column 2 reports the first-stage regression of \(\Delta \ln (1-\tau )\) on the instrument, \(\Delta \ln (1-\tau ^p)\). The point estimate on the latter is 0.633, and the F-statistic is in the hundreds of thousands, well above the standard thresholds required to certify instrument relevance. Column 3 reports the reduced-form regression of the change in log income, \(\Delta \ln (z)\) on the instrument, \(\Delta \ln (1-\tau ^p)\), which yields a point estimate of 0.204, again highly significant. These regression results are consistent with the graphical evidence provided in Fig. 2, which shows a strongly downward-sloping OLS relationship (Panel A), a strongly upward-sloping first-stage relationship (Panel B) and a moderately upward-sloping reduced-form relationship (Panel C). In the latter panel, we show the reduced-form relationship constructing the predicted change in the log of the net-of-tax rate lagged 1 and 2 years.

Column 4 reports the second-stage results using the Gruber and Saez (2002) IV strategy, without any controls for base-year income. The estimated taxable income elasticity is 0.322, with a standard error of 0.015. As discussed above, this estimate could be biased because of the lack of controls for mean reversion or heterogeneous income trends. Column 5 reports the main specification in Gruber and Saez (2002), which includes a five-piece cubic spline of log base-year income to correct for mean reversion. The estimated elasticity of taxable income is 0.356. Column 6 includes a five-piece linear spline of log taxable income, yielding a point estimate of 0.343. All estimates are highly statistically significant, thanks to the large sample size of more than four million observations. One caveat to the interpretation of these results is that the p value for the diff-in-Sargan test statistic, used to determine whether the instrument is exogenous, is close to zero in all three specifications. This implies rejecting the null hypothesis of exogenous instruments, in line with the results from Weber (2014). Therefore, the ETI estimates in columns 4–6 should be interpreted with caution.

Table 4 reports ETI estimates for the same period (1999–2014) using the two alternative estimation methods described in Sect. 4. Columns 1 and 2 report estimates for the model proposed by Kleven and Schultz (2014), which includes the (instrumented) change in log virtual income to capture income effects separately from substitution effects. The point estimates for the (compensated) ETI are 0.543 and 0.538 in columns 1 and 2, which include cubic and log splines of base-year income, respectively. The coefficients on the change in log virtual income are close to zero, suggesting that income effects are of second-order importance in this context (consistent with the earlier literature, e.g., Gruber and Saez 2002; Kleven and Schultz 2014). Columns 3 through 6 present results from the model proposed by Weber (2014), who constructs the predicted tax rate instrument using further lags of taxable income. In columns 3 and 4, we include cubic and log splines, respectively, of log base-year taxable income. We obtain ETI estimates above 0.80, substantially larger than the previous results. In columns 5 and 6, we implement the main specification proposed by Weber (2014), including lagged versions of the base-year income splines to additionally control for heterogenous income trends. This yields ETI estimates of 0.644 and 0.628. It is important to note that the Weber estimator is the only one that passes the diff-in-Sargan test of instrument exogeneity consistently, while we can reject the exogeneity of the Gruber–Saez and Kleven–Schultz instruments in these specifications.

Taken together, the results from Tables 3 and 4 indicate that the ETI estimates for Spain in the period 1999–2014 using the three most popular methods available are between 0.35 and 0.64, with the lowest estimate obtained using the Gruber–Saez estimator and highest with the Weber estimator. The fact that all estimates are broadly of the same order of magnitude suggests that the availability of a long panel dataset over a period with multiple tax reforms (combining tax cuts and increases) affecting different parts of the income distribution contributes to finding stable estimates of the ETI, which has been a challenge in this literature (see Saez et al. 2012).

5.2 Anatomy of the response

In this subsection, we explore the anatomy of the aggregate taxable income responses documented above. Table 5 reports estimates of the ETI for employees (columns 1–4) versus self-employed taxpayers (columns 5–8). In each case, we present two specifications using the Gruber–Saez’s method (with cubic and log splines), one using Kleven–Schultz’s method (with cubic splines) and one using Weber’s method (with lagged cubic splines). The ETI estimate for employees is between 0.23 and 0.47. In contrast, the ETI for self-employed taxpayers is 0.65 with the Gruber–Saez’s method, 0.93 with Kleven–Schultz’s and above 1.45 with Weber’s. The results clearly indicate that self-employed taxpayers are much more responsive to changes in marginal tax rates than wage employees. This follows economic intuition, as self-employed workers have more flexibility to adjust their taxable income for two reasons: (i) They can easily change their labor supply because they are not limited to a fixed-hours contract, and (ii) they have more scope to avoid or evade taxes, because a large share of their income is not third-party reported. The results are also consistent with a large body of evidence documenting larger responses to taxation by self-employed workers compared to employees (see, for example, Chetty et al. 2011; Kleven et al. 2011).

In Table 6, we focus on the elasticity of different types of income to the same tax reforms, as done by Kleven and Schultz (2014) in their study of Danish tax reforms. We find that labor income and financial capital income (shown in Panels A and B) are the least responsive to tax changes, with ETIs between 0.18 and 0.38 in the first case and between 0.24 and 0.32 in the second (with Gruber–Saez always yielding the lowest and Weber the largest point estimates). Real estate capital income (Panel C) is slightly more responsive, with an ETI between 0.35 and 0.49. Business income (shown in Panel D), in contrast, is highly responsive and features an ETI between 0.80 and 1.42. Notice that the sample size is different in each of these sets of regressions, because the outcome variables are defined as log changes, so any observations with zero (or negative) income automatically drop out.

We then turn to studying whether taxpayers’ responses are due to real labor supply changes, tax avoidance or tax evasion. To do this, Table 7 reports estimates of the elasticity of broad income (EBI), defined as the sum of all income sources subtracting only income-related deductions (e.g., social security contributions paid by employees).Footnote 19 The EBI provides a measure of the real (e.g., labor supply) and evasion (e.g., income underreporting) responses to taxation, whereas the ETI also accounts for avoidance responses (e.g., taking advantage of more tax deductions). As in previous tables, we report results for three different estimation methods: Gruber–Saez’s (columns 1–2), Kleven–Schultz’s (columns 3–4) and Weber’s (columns 5–6). The estimates of the EBI are between 0.10 and 0.24 in all specifications, suggesting that real and evasion responses account for about one-third of the total taxable income response to taxation. However, the relevance of reporting responses is heterogeneous across types of taxpayers. Indeed, Table 8 further explores whether wage employees and self-employed taxpayers have a different EBI. Indeed, wage employees have a very low EBI (below 0.10 across all specifications), while self-employed have an EBI around 1. These results confirm the intuition that reported income of the self-employed is much more responsive to taxation either through a real or an evasion response.

In Table 9, we shift the focus to examine the responses of reported tax deductions to changes in marginal tax rates. We follow the approach of Doerrenberg et al. (2017) and use the same identification strategy as in previous tables, but with the log change in tax deductions as the dependent variable. In these specifications, we expect to find negative point estimates because the outcome variable is the log change in deductions, which are subtracted from taxable income: If the net-of-tax rate decreases (tax increase), taxpayers will tend to claim higher deductions to lower their tax liability. Panel A of Table 9 reports estimates of the elasticity of log total deductions with respect to the net-of-tax rate. The estimates across different models range from \(-\,0.18\) to \(-\,0.45\) and are all highly significant, indicating that there is some responsiveness of deductions. Panel B shows that the estimated elasticity increases (in absolute value) to a range between \(-\,0.26\) and \(-\,0.77\) when we exclude the personal deduction, as expected because this deduction depends on taxpayer characteristics such as age and number of dependents, which are hard to modify in the short term. Finally, Panel C focuses on the deduction for private pension contributions, which is interesting for two reasons: It is the most relevant deduction in terms of foregone tax revenue and taxpayers can freely choose the annual amount they contribute to private pension plans, up to an annual maximum.Footnote 20 Taxpayers are very responsive to this particular deduction, with elasticity estimates between \(-\,0.70\) and up to \(-\,1.52\) depending on the specification. Overall, the results from this table indicate that an important part of the response to tax changes is due to responses along the reported deductions margin, in particular the deduction for private pension contributions. Hence, we conclude that an important driver of the taxable income responses in Spain over the period 1999–2014 was (legal) tax avoidance.

5.3 Robustness checks

We conduct a number of additional empirical exercises to check the robustness of our results. In Table 10, we report estimates of the ETI restricting the sample to taxpayers with base-year broad income above €5000 (Panel A) and €10,000 (Panel B), respectively. This is an often-used restriction in the literature, where it is justified as a way to deal with intense mean reversion at the bottom of the income distribution (Gruber and Saez 2002). Comparing the results in Table 10 to those in columns 5–6 in Table 3 and columns 1–2 and 5–6 in Table 4, we find that the ETI estimates are very similar. These results are reassuring because they indicate that, despite the massive mean reversion at the bottom of the distribution documented in Fig. 3, the inclusion of nonlinear controls for base-year income (cubic and log splines) is enough to make the estimates stable for all three estimation methods.

In Table 11, we present results using 2-year and 1-year differences to assess how our main estimates change under different time horizons. Up until this point, we have followed the ETI literature’s convention of analyzing 3-year differences. The rationale for this is to avoid capturing mostly anticipation responses (in the form of re-timing of reported income or deductions across years) instead of the medium-term response to tax changes. The top panel of Table 11 shows the results with 2-year differences and the bottom panel with 1-year differences. The results for the Gruber–Saez’s method (columns 1–2) and Weber’s method (columns 5–6) are similar to the baseline estimates from Tables 3 and 4. In contrast, the estimates using the Kleven–Schultz’s method are lower, between 0.14 and 0.17, although still statistically different from zero.

In Online Appendix, we report additional robustness checks, showing estimates of the Gruber–Saez’s and Kleven–Schultz’s methods with lagged base-year income splines (Table A.2), ETI estimates from a balanced panel of taxpayers present in the sample for all years between 1999 and 2014 (Table A.3), ETI estimates including pensioners (Table A.4) and, finally, ETI estimates excluding taxpayers who moved across regions within Spain during the period under analysis (Table A.5). In all four cases, we report the results for the three estimation methods with cubic and log splines (lagged in the Weber specifications). We generally obtain ETI estimates very similar to those obtained in Tables 3 and 4, providing further support to the robustness of our results.

As a final exercise, we examine the distribution of taxable income around kink points of the income tax schedule to obtain alternative estimates of the ETI using bunching methods (Saez 2010). We find very almost no bunching evidence in any period, consistent with an existing working paper by Esteller-Moré and Foremny (2016). All the histograms with the distribution of taxable income around kinks are shown in Online Appendix Figures A.1 and A.2. Note that the lack of bunching evidence does not necessarily imply that our panel-based estimates are biased, as there are well-known reasons for the bunching estimator to be biased toward zero, such as optimization frictions, inattention and career concerns (for a detailed discussion, see Kleven 2016).

5.4 Discussion of results

We conclude from these results that Spanish taxpayers’ response to tax changes are moderate, with significant heterogeneity in the response across groups of taxpayers and types of income. Given the well-known limitations of the Gruber–Saez estimator (potential endogeneity, weak controls for heterogeneous income trends and exclusion of income effects) and the results of the diff-in-Sargan test of instrument exogeneity, we consider that the most reliable estimates are those obtained using the Kleven–Schultz and, especially, Weber’s methods. In Table 4, we obtain point estimates between 0.52–0.54 (Kleven–Schultz’s method) and 0.62–0.64 (Weber’s method). In the robustness tests of Tables 10 and A.2–A.5, the ETI estimates using these two methods (with cubic or log splines) are all between 0.45 and 0.64. Therefore, we conclude that the most reliable ETI estimates for Spain for the period 1999–2014 are in the range between 0.45 and 0.64. These estimates of the ETI are on the upper part of the range of “consensus” estimates for the USA (except for a few studies such as Feldstein 1995; Mertens and Olea 2018). They are similar in magnitude to the ETI estimates for Germany (Doerrenberg et al. 2017) and substantially higher than the estimates for Denmark (Kleven and Schultz 2014).

Regarding the anatomy of the response, we highlight two important results. First, the larger ETI estimates for self-employed taxpayers and business income confirm the intuition that responses to taxation depend on both tax enforcement intensity and the availability of reaction margins (e.g., fixed-hours contracts vs. independent work). Second, the high elasticity of tax deductions indicates the relevance of avoidance responses to taxation. They also contribute to rationalizing the small estimated EBI compared to the higher ETI estimates. Nevertheless, the significant EBI estimates for self-employed taxpayers suggest that reporting responses (possibly due to real and evasion responses) are relevant for that group.

6 Concluding remarks

In this paper, we have estimated the elasticity of taxable income (ETI) using a panel of administrative tax returns from the Spanish personal income tax for the period 1999–2014. The identification strategy mainly exploits three major reforms introduced at different stages of the business cycle that had different effects on the tax schedule: a tax cut in 2003, an overhaul of the tax in 2007 and a tax increase in 2012. This identifying variation is complemented with other legislative tax changes that mainly affected average tax rates, allowing the possibility to identify and estimate the existence of income effects.

We find elasticities of taxable income (ETI) for the entire 1999–2014 period in line with the most recent evidence for advanced economies, between 0.45 and 0.64, implying moderate medium-term responses of taxpayers to changes in personal income tax rates. However, we document significant heterogeneity in the response to tax changes across groups of taxpayers and for different sources of income. In particular, estimates of the ETI for self-employed taxpayers are on average three times larger than the estimates for wage employees. Consistent with that, business income and real estate capital income exhibit stronger responses to taxation than labor income, which is subject to both stricter tax enforcement and market rigidities. In terms of the anatomy of the response, we find smaller elasticities of the broad income, in the range between 0.10 and 0.24, although they are quantitatively relevant, particularly for self-employed taxpayers. The differences in magnitude between the estimated ETI and EBI indicate the relevance of tax deductions in taxpayers’ responses. Indeed, we document an elasticity exceeding one for some tax deductions, such as the one for private pension plan contributions.

As stressed by the long-standing literature on the ETI, this elasticity is not a structural parameter and its identification is subject to multiple econometric challenges, which often result in unstable estimates. Considering these limitations, this paper presents a broad set of sensitivity analyses in order to test the robustness of our estimates. Adapting recent methodological approaches, we show that our estimates are robust to potential biases created by mean reversion and heterogeneous income trends across groups of taxpayers unrelated to tax reforms.

Notes

The full list of income sources contained in the general tax base includes labor income, business income, real estate capital income, financial capital income, some components of capital gains and other income sources such as imputed and attributed rents.

Other relevant income-related expenditures are the reported inputs acquisitions for entrepreneurs or housing expenses for landlords. Each income source has its own set of deductions and implementation rules: for instance, deductions for irregular financial capital, the deduction for home rentals or the deductions designed to promote entrepreneurial activity and employment.

Some examples of general deductions are those associated with personal and family circumstances (individual allowance, joint filing, number of children and dependents), the deduction for contributions to private pension plans and allowances related to past negative tax liabilities.

The flat tax rate was 17% in 1999, 18% from 2000 to 2002, 15% from 2003 to 2006, again 18% since 2007 until 2010 when certain progressivity was included. See Sect. 3.2 and Online Appendix A for more details.

Apart from these, there is a broad set of smaller (in revenue terms) tax credits for house renting, double taxation, business investment and charitable donations. A complementary discussion of the structure of the Spanish PIT and its main components can be found in García-Miralles et al. (2019).

For historical reasons, the autonomous communities of the Basque Country and Navarre (which account for 6% of Spain’s population) have the power to design, collect and enforce their own PIT. For this reason, they are not included in this study.

See Online Appendix A for references to the bills that introduced the major tax reforms in the Spanish personal income tax as well as a simplified description of other relevant legislative tax changes also considered in the empirical analysis.

Gil et al. (2019) estimate the ex ante tax revenue impact of all recent PIT reforms in Spain based on a narrative description of the reforms, using detailed information reported by the Spanish Tax Agency.

Before this reform, capital gains derived from the transmission of assets whose generation period was inferior to 1 year (2 years in 1999–2000) were included in the general tax base. From 2007 to 2012, only residual capital gains not associated with the transmission of assets, e.g., net changes in wealth, were included in the general tax base. In 2013, short-term capital gains (up to 1 year) derived from assets transmission were included again in the general tax base.

Except for those from the Basque Country and Navarre, as explained in footnote 7.

To calculate all the statistics reported in Table 1, we apply the sampling weights contained in the data.

We describe the tax calculator in more detail in Online Appendix B, and the full code is available from the authors upon request. Table A.1 in Online Appendix reports the percentage of observations in which taxable income and tax liability calculated with our tax calculator are within 2% of the actual values recorded in the administrative panel dataset of tax returns. The accuracy rates are always above 97.5%, and in many years they reach 100%.

In less than 2% of observations, income is negative for at least one source (often business income). To ensure that the weights in the formula add up to one for these observations, we apply a normalization. We redefine the income shares for these observations as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} {\hat{s}}_{it}^{j}\equiv \frac{\text {max}(0,s_{it}^{j})}{\sum _{j}\text {max}(0,s_{it}^{j})} \end{aligned}$$.

See Kleven and Schultz (2014, p. 282), for a discussion.

For expositional simplicity, we omit the first-stage equation for the change in virtual income, which is similar to Eq. (3).

Kleven and Schultz (2014) reach a similar conclusion for Denmark.

We do exclude from the definition of broad income all types of capital gains, for the reasons discussed in Sect. 3.3.

The maximum deductible annual contribution amount was €24,250 between 2003 and 2007 and then lowered to €12,500 in 2007 (€10,000 for taxpayers under 50 years).

References

Arrazola M, de Hevia J, Romero D, Sanz JF (2014) Efecto de los Tipos Marginales del IRPF Sobre los Ingresos Fiscales y la Actividad Económica en España: Un Análisis Empírico. FUNCAS working paper 740

Auten G, Carroll R (1999) The effect of income taxes on household income. Rev Econ Stat 81(4):681–693

Badenes N (2001) IRPF, Eficencia y Equidad: Tres Ejercicios de Microsimulación. PhD thesis, Instituto de Estudios Fiscales INV. 1/01

Chetty R (2009) Is the taxable income elasticity sufficient to calculate deadweight loss? The implications of evasion and avoidance. Am Econ J Econ Policy 1(2):31–52

Chetty R, Friedman JN, Olsen T, Pistaferri L (2011) Adjustment costs, firm responses and micro vs. macro labor supply elasticities: evidence from danish tax records. Q J Econ 126(2):749–804

Díaz-Caro C, Onrubia J (2018) How do taxable income responses to marginal tax rates differ by sex, marital status and age? Evidence from spanish dual income tax. Econ Open-Access Open-Assess J 12(2018–67):1–24

Díaz-Mendoza M (2004) La respuesta de los contribuyentes ante las reformas del IRPF, 1987–1994. CEMFI master’s thesis no. 0405

Doerrenberg P, Peichl A, Siegloch S (2017) The elasticity of taxable income in the presence of deduction possibilities. J Public Econ 151:41–55