Abstract

In this paper we apply the meta-regression technique to survey the empirical literature on the economic incidence of labour taxes and social security contributions. In particular, we focus on the effects of taxation on wages to test the conventional view that employees bear the burden due to lower net wages. Based on 52 empirical papers, we find that economic institutions, the tax wedge definition, and the temporal focus significantly affect the results. In the long run, workers bear between two thirds of the tax burden in Continental and Anglo-Saxon economies, and nearly 90 % in the Nordic economies. However, despite the numerous set of controlling variables, a significant part of the variability of the empirical literature remains unexplained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The reduction in labour taxes is a widespread policy recommendation for raising employment (see, for instance, the seminal reports from the European Commission 1994; OECD 1994). In broad terms, labour taxes (i.e. personal income tax and social security contributions) drive a wedge between labour costs and net wages and have a negative effect on labour supply, structural employment and hours worked. From the academia, Prescott (2004) triggered the debate by attributing all the difference in labour utilization between the US and Europe to direct taxes. This author calibrated a labour supply model and found out that the divergence in hours worked per week among the working-age population since the 1970s between the US and France and Germany could be explained by differences in marginal tax rates on labour. In a similar line of research, Coenen et al. (2008) employed a calibrated version of the New Area-Wide Model developed at the ECB to simulate the effects of establishing a ‘US fiscal system’ in the euro area. The analysis showed that the reduction in employer social contributions to the levels prevailing in the US (from 21.9 to 7.1 % of labour costs) may increase output by more than five points, hours worked by more than 6 % and real wages slightly less than 13 %. These results generated a lively debate.Footnote 1

Based on this assumption, since the 1990s many European governments have followed this tax reform path, cutting social security payroll taxes for cyclical and structural reasons. For instance, since 1997 Spain has cut social security payroll taxes for permanent contracts and for population groups affected by long-term unemployment. Recently, the new government has announced a reduction in employer social contributions (1 p.p. in 2013 and another point in 2014), compensated by an increase in value added taxation. Since 2000, France encouraged the transition to the 35-hour week with lower employer social security contributions. In 2007 and 2008 Germany introduced cuts in unemployment insurance contributions, financed by a higher value added tax rate. Finally, in the midst of the recent international crisis, the US Congressional Budget Office (2008), for instance, considered the reduction in social contributions to be one of the most effective measures for responding to short-term economic weakness, albeit subject to lags and uncertainty.

Despite these common developments, there remains a significant fiscal gap within OECD countries. As Fig. 1 shows, the direct tax wedge (income tax, employee and employer payroll taxes) for a two-earner household with two children is well over 40 % in France, Italy and Germany, while Anglo-Saxon economies and Japan limit the burden to approximately 25–30 %.

The economic effects of taxation depend ultimately on the long and short-term economic incidence, i.e. on who really bears the burden. In the case of employer social contributions, they can be borne by the employers (ultimately reducing the firm’s profits), they can be shifted backwards to employees (reducing net wages), or they can be shifted forward to consumers (increasing the price level). Most of the previous papers calibrate this effect.

Empirical literature shows mixed results. In a classic survey, Hamermesh (1993) analysed 15 seminal studies on the economic incidence of payroll taxes, mainly social security contributions. The author rejected any robust conclusion, not even a consensus interval: results ranged from full to null shifting. By surveying recent studies, Arpaia and Mourre (2005) confirmed that taxation increased unemployment but they also highlighted the complexity of its interactions with other labour market and economic institutions. The European Central Bank (2008) documented the disincentives to work (particularly for low-income workers) stemming from high marginal tax rates. In a similar vein, Keane (2011) reviewed the literature on labour supply by gender. Once again, there appears to be a considerable controversy over their response to changes in wages and taxes. This is especially the case for men, due to differences in the measurement of wages and human capital (for women most studies find a large labour supply elasticity).

This is the appropriate field for the meta-analysis approach. In contrast to these narrative surveys, meta-analysis allows revising the relevant empirical literature in a more formal and objective manner. As summarised by Stanley and Jarrel (1989),Footnote 2 meta-analysis starts with the compilation of an exhaustive sample of literature and the choice of the dependent variable (in our case, the degree of backward shifting of labour taxes, proxied by the estimated elasticity of net wages to taxation). A general set of ‘moderators’, i.e. variables that reflect the quantitative and qualitative features of the different studies that could be influencing their results (theoretical model and sample, among others) is then selected and tabulated using dummy variables. The meta-regression of the dependent variable on these moderators can be used to quantifying the‘ true dependent variable‘, that is, the consensus result of the empirical literature on the effect of taxes on wages after controlling for methodological differences. And also, and probably more important, meta-analysis permits to show which aspects of the modelling, data and econometric techniques are important, or not, for the estimates.

A sensible starting point is Fuchs et al. (1998). Based on a survey of economics departments at 40 leading US universities, the authors conclude that employers bear 20 % of firm social contributions, while employees bear the remaining 80 % via lower net wages. In other words, the conventional wisdom, in line with public economics textbooks, is that the relatively higher rigidity of labour supply with respect to labour demand determines that the market adjustment is mainly concentrated on wages, and not on employment.Footnote 3

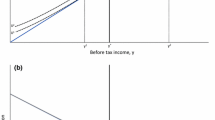

Figure 2 generalises this framework, taking into account wage bargaining and firm market behaviour, as suggested by Layard et al. (1991). In this ‘wage-setting schedule’, real wage accepted by workers (adjusted for trend growth in labour efficiency) varies with the unemployment rate: the higher the unemployment rate, the lower real wages will be. The position of the wage-setting schedule is influenced by a number of structural characteristics, such as the degree of trade union power, the generosity of unemployment benefits, the stringency of employment regulations or the efficiency of the matching process and, related to it, the centralisation of the wage-employment bargaining. The empirical literature confirmed the role of the centralisation of wage bargaining and union presence. Centralised economies with strong unions such as the Nordic counties, or decentralised wage bargaining with weak unions as the Anglo-Saxon exhibit better performance than the Continental and Mediterranean. We will develop this issue afterwards. In this context, an increase in labour taxation (e.g. employer social security taxes, SST in the Fig. 2) would generate a downwards shift of the labour demand curve (‘price-setting schedule’). Market equilibrium would move from A to B, generating a limited negative effect on the employment rate (from N to N’), since labour costs hardly increase (from W to W’). Workers would bear the major part of the tax burden (BD over BC), since net real wages fall from w to w’.

The main goal of this paper is to test whether this estimate of the economic incidence of labour taxation is consistent with the empirical literature on the subject. To do so, we quantify the effect of the different methodological approaches, and temporal and geographical coverage. We think we are the first to perform a meta-analysis of the incidence of labour taxes and social contributions. We place more weight on the methodological variables that stem from economic theory or from generally accepted empirical results, such as those related to nominal rigidities, the wage bargaining characteristics or the pension system design.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we present a brief description of the empirical literature of taxation and wages/labour costs, with a focus on social contributions. In Sect. 3, we report the basic methodology and the results of the meta-analysis regressions. They are grouped under three headings: ‘basic moderators’ that capture country and temporal fixed effects, ‘economic moderators’ to control the impact of the most relevant economic features and ‘other moderators’, mainly reflecting the econometric techniques. We also perform various robustness checks, based on the sample of estimates, the econometric methods and the procedure of specification selection. Finally, in Sect. 4 we present the main conclusions and general economic policy recommendations.

2 A brief survey of the empirical literature

2.1 Basic methodology

Public economics literature highlights two alternative definitions of the nature of social contributions. On the one hand, they can represent a deferred salary if the link between social contributions and social benefits (pensions and unemployment benefits) is high. This is the case of pension systems with defined contributions. On the other hand, they might be considered a regular payroll tax (such as the labour income tax), if the tax-benefit link is weak, as is the case in many defined-benefit pay-as-you-go pension systems. In this paper we opt for an intermediate position, so social contributions would be treated as a particular labour tax whose revenues are partially affected by social security financing. Therefore, we will concentrate on the labour market dynamics to analyse the incidence of social contributions and, in general, of labour taxes.

The focus will be placed on their economic incidence, i.e., who effectively bears the tax burden and what are its main economic effects (on wages, labour costs and equilibrium employment), rather than on the legal incidence.Footnote 4 This involves analysing the change in behaviour of economic agents after the establishment of the tax. As mentioned above, in the case of social contributions the literature points at two basic shifting processes. Consumers may bear the burden if firms have enough market power to adjust prices to the new tax rates. This is known as forward shifting. Alternatively, employees may bear the burden if the firm offsets the new tax burden with a (net) negative wage variation, leaving labour costs constant, a process known as backward shifting.

Therefore, the benchmark equation in the studies takes the form of a general wage equation

where Wstands for the net nominal wage or the nominal labour cost (transformed in logs), P for the price level (the output or the consumption deflator), Y/N is the labour productivity, U the unemployment rate, TAX stands for the tax wedge (again in logs), and X is a set of control variables. Focusing on the latter, theoretical and empirical literature shows that tax incidence depends not only on competitive factors (such as labour supply and demand elasticities, and factor substitutabilityFootnote 5), but also on the effect of economic institutions such as the degree of wage bargaining centralisation and union power, employment protection legislation, unemployment benefits, minimum wages and social security fairness (we will develop these issues in Sect. 3). Finally, functions f and h denote levels or growth rates (long or short run results), and g is generally a linear function of the regressors. Every variable is specified for country or population group i, and time t.

Therefore, the dependent variable is the net wage elasticity to taxes. As previously stated, this figure proxies the degree of backward shifting. A \(-\)1.0 coefficient represents the full shifting scenario, where workers bear 100 % of taxes. A null elasticity implies that workers do not bear even part of the tax (null shifting). Intermediate results are more frequent and imply partial shifting processes.Footnote 6

2.2 Database

We have assembled a database of 670 estimates of the impact of taxes on net wages from 52 papers, covering most of the OECD countries and some Latin American economies.Footnote 7 This sample is based on a narrative survey (Melguizo 2009), updated using the IDEAS search engine.Footnote 8 We normalised the results to the wage elasticity (based on the labour cost-wage equation equivalence explained in footnote 6), and directly chose this variable as the dependent one.

We restricted our core sample to the preferred estimate in each study for each country or region covered, based on the author’s judgement (when absent, we use the usual statistic tests). This limited the sample to 124 observations from the 52 papers since some of the papers report estimates for different regions (labelled ‘baseline sample’). This option remains open in the meta-analysis literature. Some authors claim that excluding some estimates may bias the studies, weakening the main advantage of meta-analysis over other surveying techniques. However, the inclusion of all the estimates is not cost-free: it may bias the analysis towards those studies that report more results for each country (if their results are similar), or may increase the variability of the results even if the authors manifest their preference for certain estimates (if their results vary).

Table 1 presents the list and definition of the moderators, while Table 2 summarises the main statistics of this baseline sample. On average, a 1.0 % increase in taxation reduces wages by 0.66 %. Therefore, overall employees bear two thirds of social security contributions. However, consistent with the mixed results of narrative surveys, studies display a very high dispersion of estimates, ranging from 0.91 to \(-\)2.54. This significant dispersion can be due to differences in the statistical methods or the temporal and geographical coverage, or can stem from different institutional designs. Depending on the main methodological alternatives, the highest degree of shifting is obtained in cross-section analysis and in book publications and mimeos, where the elasticity is around \(-\)0.90. By contrast, studies focused on Continental and Mediterranean economies or published in journals tend to limit the elasticity to \(-\)0.50 approximately.

As mentioned above, the empirical literature highlights the role of economic institutions, particularly the centralisation of wage bargaining and union presence. Centralised economies with strong unions or decentralised wage bargaining with weak unions exhibit lower unemployment rates. In addition, public sector effectiveness may compensate the disincentives from a high taxation, since workers perceive the tax-benefit linkage. Broadly speaking, Nordic and Anglo-Saxon economies have the systems with the best equilibrium, while Continental and Mediterranean economies tend to be placed in an unfavourable intermediate position.

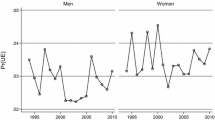

Figure 3 supports this hypothesis suggesting that Nordic economies, characterised by their high centralisation, strong trade unions and effective governments are different. The mode estimate is full shifting (\(-\)1.0 elasticity), while in Anglo-Saxon, Continental and Mediterranean economies workers seem to bear half of the tax burden (\(-\)0.5).Footnote 9 Are these differences statistically significant? Do the a priori results hold when controlling for the complete set of methodological differences? The aim of the meta-analysis performed in the next section is precisely to answer these questions quantitatively.

3 Meta-regression analysis

3.1 Meta-analysis approach

Given the relatively recent arrival of the meta-analysis technique in economics, there is no standardised empirical strategy. As previously explained, we restricted the sample to 124 observations (from a complete sample of 670 observations), although we will use the complete dataset to test the robustness of the results. Due to the presence of some extreme values in the sample, robust regression estimation is recommended.Footnote 10 We will also include some weighted least squares (WLS) estimates to control the quality of the studies.Footnote 11

We opt for a sequential approach, in line with Knell and Stix (2003), Evers et al. (2006) and Card et al. (2010). Firstly, we test the significance of geographical and temporal (by decades, from the 1950s to the 2000s) moderators, in the spirit of panel-data fixed effects estimation. This enables a basic specification to be obtained, in which we will include the main economic and methodological moderators as a second step (see Table 1, for the complete set). Instead of including all of these moderators simultaneously, we opt to include them one by one to avoid multicollinearity problems. Afterwards, we incorporate the significant moderators in a combined specification. As a final check, we perform an extreme-bounds analysis to evaluate whether results are influenced by the sequence of estimations.

In what follows, we will concentrate on reporting the significant results and focus on the role of economic moderators, which naturally suggest economic policy recommendations.Footnote 12 The meta-regression specification, based on Eq. 1, is straightforward

where \(\varvec{\beta }\)\(_\mathbf s \) is the reported wage elasticity to taxes in study s (defined as the impact of taxes on net wages), b is the ‘true’ elasticity, \(\varvec{\alpha }\)\(_\mathbf{s,i }\) and \(\varvec{\alpha }\)\(_\mathbf{s,t }\) are vectors with geographical and temporal ‘fixed effects’, X\(_\mathbf s \) is a vector of moderator variables, and u\(_\mathbf s \) is the error term. The independent variables are represented by dummies (for instance, if a study sample covers the period 1980–2008, D50 to D70 will be marked as a column of 0s for the particular study, while D80 to D00 will be represented by a column of 1s). X\(_\mathbf s \) will basically reflect imperfect competition variables stemming from the theoretical and empirical literature, such as the public sector effectiveness, labour market institutions (unions, wage bargaining), social security rules and tax wedge mix.

3.2 Results

Baseline specification (‘fixed effects’ moderators)

Firstly, we aim to obtain a baseline specification in the spirit of the fixed-effect panel estimation. Alternative estimations rejected robust geographical effects (we tested for differences in studies covering Latin America, Spain and the US vs. other OECD economies). For this reason, and since some of the economic moderators may be correlated, the basic specification does not include them. No significant temporal fixed effects, defined by the sample period in the data used (identified by the decades covered in case of time series analysis), are found either.

Another issue that should be controlled from the beginning in order to avoid spurious results is the presence of publication bias. It may arise from the tendency to report and/or to publish only the significant results, rejecting the null hypothesis of no effect. In order to reduce its potential influence, we included in our meta-database both published and unpublished papers. More than one third of the sample, 45 estimates, comes either from working papers or mimeos (see Table 2).Footnote 13

Based on the previous elements, in this initial benchmark specification the wage elasticity to taxes is \(-\)0.65, so workers bear almost two thirds of the tax burden (column I in Table 3).

Economic moderators

The attention devoted to the economic effects of labour taxation from international organisations, policy makers and academia ranks among the highest in applied macroeconomics, generating an enormous amount of research. However, the main issues affecting our results can be restricted to the following: the role of taxes under different institutional settings, the tax wedge composition, short- vs. long-run results and the role of the social security scheme.

Economic institutions matter. The theoretical and empirical literature shows that the impact of labour taxes on labour costs and unemployment is higher in economies with an intermediate centralisation of the wage bargaining process and a strong trade union presence (see Calmfors and Driffill 1988; Alesina and Perotti 1997; Daveri and Tabellini 2000). In this context, common to Continental and Mediterranean countries, the discipline effect of competition or the internalization of externalities are weak. This contrasts with the behaviour in decentralized Anglo-Saxon economies, and unionized centralized Nordic countries. Our analysis partially confirms this hypothesis. Column II in Table 3 shows that the average elasticity is \(-\)0.59. However, the degree of shifting is much higher in Nordic countries at \(-0.79 (-0.59- 0.20)\). This could be an indicator of the benefits of good governance, since Nordic public sectors are among the most effective (see Sapir 2006). By contrast, no significant differences were found between Anglo-Saxon and Continental-Mediterranean economies.

Throughout this paper we use the terms ‘tax wedge’, ‘labour taxation’ and ‘social security contributions’ in a flexible way, implicitly accepting the tax invariance theorem. However, there are several reasons to justify a differential impact of the fiscal wedge components. Focusing on social contributions, even though they are usually a payroll tax, their tax base and tariff usually differ from those of personal income taxes (not to mention the linkage effect), and consumption taxes (see OECD 1990, 2007). Additionally, the salary wedge includes the price wedge, that is, the gap between producer and consumer prices.

Formally, we define pit as the personal income tax effective rate, essc the employee social security contributions rate, fssc the firm social security contributions rate, ctthe consumption tax rate, pp the domestic output deflator, pp* international prices deflator, \(a\) the share of domestic products in the consumption basket, and \(e\) the exchange rate. The ‘salary wedge’ (wedge between the nominal labour costs and the net real wage) can be defined as \(\left[ {\frac{( {\text{1+ct}})( {\text{1+fssc}})}{( {\text{1-pit}})( {\text{1-essc}})}} \right]\left[ {\frac{\text{ epp*}}{\text{ pp}}} \right]^\mathrm{{1-a}}\). The ‘fiscal wedge’ includes exclusively the tax components of the salary wedge and can be expressed as \(\left[ {\frac{( {\text{1+ct}})( {\text{1+fssc}})}{( {\text{1-pit}})( {\text{1-essc}})}} \right]\). The ‘direct tax wedge’ only focuses on taxes on income as \(\left[ {\frac{( {\text{1+fssc}})}{( {\text{1-pit}})( {\text{1-essc}})}} \right]\) and, finally, the ‘employer social taxes wedge’ can be written as (1+fssc).

Therefore, we tested the impact of alternative fiscal wedge definitions, starting from the general salary wedge (fiscal wedge plus price wedge), down to employer social security contributions. Results confirm that different taxes have different effects on wages. While the elasticity of net wages to labour taxes is \(-\)0.59, the salary and fiscal wedge impact (inclusive of indirect taxes and of price wedge between output and consumption in the first case) is close to 80 % (\(-0.79 = -0.59-0.20\), as shown in column III in Table 3).

Moreover, as highlighted in Hamermesh (1993), the presence of lags in the shifting of social contribution is usually significant (on average, long-run shifting equilibrium takes more than a year) due to the presence of nominal rigidities. Our estimation confirms this point (column IV in Table 3). The short-run elasticity \(-0.43 (-0.74 + 0.31)\) is lower than the long-run counterpart, \(-\)0.74. Therefore, workers bear less than half of the tax burden in the short run (generally represented by results during the year of the tax change).

Finally, a key institutional issue that has to be tested is related to the social security scheme. In particular, the literature highlights a potential role of the ‘linkage effect’, that is, the perception of the link between contributions and social benefits (see Gruber and Krueger 1990; Gruber 1994a; Gruber 1994b; Disney 2004). Social contributions would have no effect on the equilibrium employment rate if agents perceive a full linkage effect, since they become a deferred salary (positively shifting the labour supply curve). This tends to be the case in contributory Bismarckian social security systems, in contrast to redistributive pension systems à la Beveridge. Our empirical analysis obtains the expected sign, since shifting is lower in more redistributive systems, but the effect is not significant (coefficient 0.10, column VIII in Table 6).Footnote 14

Other moderators

A second set of moderators tries to reflect methodological differences, from both the data (economy-wide or private sector, and its frequency) and the estimation techniques (cross-section, time series or panel, and selected estimator). Our analysis suggests that data coverage is relevant. Studies that refer to the entire economy, and not just the market economy, tend to show higher negative elasticities, \(-0.73 (-0.52-0.21\); column IX in Table 6). We are not convinced of its implications, since wage bargaining in the public sector is not competitive. Finally, more than half of the papers include labour costs, rather than the net wage, as the dependent variable. Those studies tend to obtain a higher negative elasticity (\(-0.80 = -0.43-0.37\); column X in Table 6), although no economic implication seems straightforward either.

Combined results

To conclude, we incorporated all the individually significant moderators into the specification (column V in Table 3). Every coefficient keeps its sign, but only the temporal focus and the dependent variable definition remain significant. Finally, column VI (Table 3) presents our baseline specification, focused on the moderators that have a more solid economic foundation. In this case, the net wage elasticity is \(-\)0.70, so workers bear 70 % of the tax burden via lower wages (or lower wage increases), somewhat lower than the starting estimate surveyed in Fuchs et al. (1998). In the Nordic economies the degree of shifting is higher, close to 90 % (\(-0.88 = -0.70-0.18\)), so nearly all the tax changes are offset by negative wage variations. Finally, we confirm that shifting takes time, and in the short run workers bear less than 40 % of the tax burden (\(-0.39 = -0.70 + 0.31\)).Footnote 15

3.3 Robustness checks

In order to further check the robustness of the results, we first tested whether the main results hold for the whole sample (670 elasticities from the 52 papers). Results, reported in columns XI to XV in Table 6, are in line with the ones reported for the core sample. These additional tests confirm that shifting is higher in Nordic economies, in studies that include indirect taxes in the tax wedge and in the long run. However, only the latter is significant. The publication bias hypothesis seems also present, with the aforementioned caveats on its downsizing effects to the sample. Taking all these considerations on board, our baseline specification for the complete sample is reported in column XIV. The net wage elasticity is \(-\)0.85, so workers bear 85 % of the tax burden. In the short term the backward shifting process is lower as well (\(-0.51 = -0.85 + 0.34\)).

Additionally, we performed a quality control study of the literature other than the publication format (books, journals, working papers and mimeos). Specifically, we used Google Scholar to weight each estimate for the number of citations.Footnote 16 The weighted least square estimation of the baseline sample is reported in columns XVI to XVIII in Table 6. In comparison to our baseline specification, estimates confirm that taxation shifting is significantly lower in the short run. However, the shifting degree seems higher, and does not depend on the economic model.

Finally, we tested how sensitive results are depending on the specification selection procedure. In particular, we calculated the confidence intervals of the impact of taxes on wages, based on the ‘extreme-bounds analysis’.Footnote 17 The lowest bound is obtained including fixed effects and controlling for the study coverage (ECO) and the publication format (BOOK, WP + MIM): \(-\)0.10 (\(-\)0.45 minus two standard errors). The highest one stems from a specification with the social security model (BEVSS) and the time horizon (DEPVAR): \(-\)1.09 (\(-\)0.77 plus two standard errors). Therefore, this test robustly rejects the no-shifting hypothesis.

4 Conclusions

In this paper we have applied the meta-regression technique to analyse the results from the empirical literature on the economic incidence of labour taxes and social contributions. In particular, we have focused on the effects of taxation on wages to find out whether employees bear the tax burden due to lower net wages. This is a relevant question, due both to the significant dispersion of the results found in the literature and to its economic policy implications.

We have based our empirical analysis on an original database of 52 empirical papers, from which we extracted 124 estimates. On average, in the core sample a 1.0 % increase in taxation reduces wages by 0.66 %. Therefore, in line with the literature on distributive incidence, employees would bear nearly two thirds of social security contributions. However, the literature exhibits a very high degree of variability.

The meta-regression analysis suggests that this figure is affected by basic economic institutions (summarized in three models, namely Anglo-Saxon, Continental-Mediterranean and Nordic), and by the tax wedge definition (in particular, the inclusion of indirect taxes). In our preferred specification, the elasticity of wages to taxes is \(-\)0.70 in the default option (i.e. a non-Nordic economy in the long run). Therefore, workers bear 70 % of taxes. In the Nordic economies the degree of shifting is close to full (\(-\)0.88), so all tax changes are almost entirely offset by a wage variation. Moreover, the impact of taxes on wages differs in the short term. The degree of shifting is much lower in the short run: workers bear less than half of the tax burden. Finally, although not included in our preferred specification, consumption taxes may be more prone to shifting.

The robustness checks carried out using the complete set of estimates, alternative estimators and extreme-bounds analysis confirm this result. However, despite the numerous set of controlling variables, a significant part of the differing conclusions found in the empirical literature studied remains unexplained. A first extension would be to estimate the combined effect of the moderators. Additionally, future research may focus on the heterogeneity (by age, sex and skill of the workers, or by industries) or on the direct effect of taxes on unemployment.

With conventional caution, some potential economic policy implications can be drawn from these results. Firstly, policy makers should take into account that even if higher social security contributions have a limited effect on employment in the long run, these are not entirely negligible, especially in the short run. This fact poses limits to strengthening social protection systems via higher revenues. Secondly, intermediate results pointed to significant employment gains from a revenue-neutral tax reform, increasing consumption taxes and lowering labour taxes. Obviously, this tax shift might also involve some problematic aspects, namely a short-term inflationary effect and a change in income distribution, which should be evaluated. Finally, our estimates support that taxation in Nordic economies, characterized by a high coordination of wage bargaining and effective public sectors, is more employment-friendly.

Notes

These findings are supported by Ohanian et al. (2006) for a wider sample of economies. Other authors have suggested complementary or alternative explanations. Nickell (2003) points to social protection rules, Blanchard (2004) to preferences, Alesina et al. (2006) to the role of labour protection and unions, Rogerson (2007a) to taxes and technological progress and Ljungvist and Sargent (2007) and Rogerson (2007b) to social benefits and the use of revenues.

This technique is being increasingly applied in labour economics. See, among others, Jarrell and Stanley (1990) for the analysis of unions and wage gap, Card and Krueger (1995) for minimum wages and employment, Nijkamp and Poot (2005) and European Commission (2005) for real wage elasticity, Longhi et al. (2006, 2007) for immigration, wages and employment, Evers et al. (2006) for taxes and working hours and Card et al. (2010) for active labour policies evaluation. By contrast, we are not aware of any meta-analysis applied to the economic incidence of either labour taxation or social contributions. See also Stanley (1998) for a meta-analysis of the Ricardian equivalence.

This degree of shifting is coherent with the labour supply and demand elasticities reported in the survey: 0.15 and \(-\)0.50 respectively. In partial equilibrium, shifting can be calculated as the ratio \(0.50/[0.15 - (-0.50)]\), so that the implied estimate is 0.77 (see Fullerton and Metcalf (2002)). Therefore, employees would bear 77 % of social security tax burden. Roughly speaking, the simulations by Coenen et al. (2008) imply a shifting of nearly 86 %, since real wages increase 12.7 % following the reduction by 14.8 percentage points in firm social security contributions. A similar exercise calibrated for the Spanish economy by Boscá et al. (2009) reduces the share borne by firms to very close to the stylized figure (76 %: a 15 % cut in firm contributions leads to an increase of 11.4 % of real wages).

Additionally, public economics literature defines differential incidence as that in which analysis is focused on the economic effects of substituting one tax by another, leaving total revenues constant. Finally, distributive incidence focuses on the income distribution effects of taxes.

See Fullerton and Metcalf (2002) for a complete revision of tax incidence.

Sometimes, the dependent variable of equation 1 is defined as the labour cost, that is, inclusive of employer social security contributions, W = w(1 + SST). In this case, tax elasticities would range between 0.0 (equivalent to \(-\)1.0 in the wage equation, if there is a full internal compensation of wages and taxes that leave labour costs constant), and 1.0 (equivalent to 0.0 in wage terms, when a tax increase fully impacts labour costs). We will use this equivalence in the next section to standardize our sample.

Latin American economies are particularly interesting due to the implementation of structural pension reforms (starting in 1981 in Chile, and followed in the mid-1990s in Argentina, Colombia, Mexico and Peru among others), which legally changed the nature of social security contributions from being a tax to a deferred salary.

http://ideas.repec.org. To be precise, in August 2009 we searched for references that contained either in the title, among the keywords, or in the abstract the terms: ‘social contributions’, ‘social security taxes’, ‘labour taxes’, ‘social taxes’, ‘payroll taxes’, ‘incidence social contributions’, incidence social security taxes’, ‘incidence labour taxes’, ‘incidence social taxes’, ‘who bears’, ‘tax burden’, ‘wages and taxes’, ‘labour costs and taxes’, ‘tax shifting’, ‘backward shifting’ or ‘forward shifting’.

As programmed in Stata 11 using ‘rreg’. We also estimated the specifications using quantile regressions (‘qreg’), obtaining very similar results. Estimations are available upon request.

In a previous version of the paper, we opted for ordinary least squares (in line with Stanley and Jarrel (1989)), controlling the effects of four statistically identified outliers (Brittain 1972; Argimón and González-Páramo 1987; Anderson and Meyer 1998; Hamaaki and Iwamoto 2008). As an additional robustness check, we estimated most of the specifications truncating the elasticity values to those set in the economic theory, i.e. from 0.0 to 1.0. In both cases, results are very similar to those reported in the main text. Estimations are available upon request.

See Table 6 for additional specifications. The complete set of estimates is available upon request.

As an additional way to control for the possible publication bias, we included as an additional regressor the standard error of the estimates. Unfortunately, its reporting is neither unanimous (50 out of the 124 results in our meta-database did not include them), neither homogeneous (some authors report standard errors, some others robust standard errors). In any case, we carried out the estimations, and found out mixed results. As shown in Table 6, robust regression estimation (specification VII) results suggest its presence, while WLS (specification XVII) rejects it. For a detailed explanation of this issue and other methodologies to test it based on the sample size, see Ashenfelter et al. (2000).

The absence of gains from an increase in the actuarial fairness of the social security (i.e. lower redistribution) may stem from a divergence between the institutional design and its perception. Boeri et al. (2001) highlight a significant lack of knowledge on basic social security institutional issues in the main economies of the EU (e.g. on the basic pay-as-you-go functioning, or even on the tax rates). In this context, a theoretically more efficient institutional setting may not fully generate its potential benefits.

The selected specification passed the basic econometric tests of heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation, once we ordered the papers by year of publication at the conventional significance levels.

http://scholar.google.com, accessed December 24, 2009. The 52 papers accumulated 5.927 citations, Alesina and Perotti (1997), Gruber (1994b); Gruber (1997) and Layard et al. (1991) being the most popular. The weight factor is the share of its citations on the total amount, divided by the number of reported preferred estimates. Alternatively, other authors use the citations reported in the ISI Web of Knowledge (see, for instance, European Commission 2005). However, this source restricts the sample to papers published in JCR journals to almost half of them, excluding some of the most popular references. In any case, the correlation between the alternative weighting factors is quite high. See Table 5 in the Appendix for more details.

Incidence and empirical growth analysis are both exposed to multicollinearity problems, given the variety of relevant factors highlighted in the literature. This makes difficult to choose its key determinants from exhaustive specifications. Results may also be biased in reduced specifications depending on the inclusion order of the regressors. Levine and Renelt (1992) proposed an automatic procedure to analyse the determinants of growth, based on computing the ‘extreme bounds’ computed from all the combinations of regressors. We concentrated on the economic incidence parameter (coefficient b in Eq. 2), estimating 21 specifications, which are available upon request.

References

Alesina A, Perotti R (1997) The welfare state and competitiveness. Am Econ Rev 87(5):921–939

Alesina A, Glaeser E, Sacerdote B (2006) Work and leisure in the US and Europe: why so different? In: Gertler M, Rogoff K (eds) NBER book series NBER macroeconomics annual 2005, vol 20. The MIT Press, Massachusett, pp 1–64

Anderson PM, Meyer BD (1997) The effects of firm specific taxes and government mandates with an application to the US unemployment insurance program. J Public Econ 65(2):119–145

Anderson PM, Meyer BD (1998), Using a natural experiment to estimate the effects of the unemployment insurance payroll tax on wages, employment, claims, and denials. NBER working paper no 6808

Argimón I, González-Páramo JM (1987) Traslación e incidencia de las cotizaciones sociales por niveles de renta en España 1980–1984. Documentos de Trabajo 01/1987, FIES

Arpaia A, Carone G (2004) Do labour taxes (and their composition) affect wages in the short and the long run? Economic papers no 216. European Commission

Arpaia A, Mourre G (2005) Labour market institutions and labour market performance: a survey of the literature. Economic papers no 238. European Commission

Ashenfelter O, Harmon C, Ossterbeek H (2000) A review of estimates of the schooling/ earnings relationship, with tests for publication bias. NBER working paper no 7457

Baicker K, Chandra A (2006) The labor market effects of rising health insurance premiums. J Lab Econ 24(1):609–634

Bell B, Jones J, Thomas J (2002) Estimating the impact of changes in employers’ National Insurance Contribution on wages, prices and employment. Bank Eng Q Bull winter, pp 384–390

Blanchard OJ (2004) The economic future of Europe. J Econ Perspect 18(4):3–26

Boeri T, Börsch-Supan A, Tabellini G (2001) Welfare state reform. A survey of what Europeans want. Econ Policy 32:9–50

Boscá JE, Ferri J, Doménech R (2009) Tax reforms and labour-market performance: an evaluation for Spain using REMS. Moneda y Crédito 228:145–196

Brittain JA (1971) The incidence of Social Security payroll taxes. Am Econ Rev LXI(1):110–125

Brittain JA (1972) The payroll tax for social security. The Brookings Institution, Washington

Brunello G, Parisi ML, Sonedda D (2002) Labor taxes and wages: evidence from Italy. CESifo working paper no 715

Calmfors L, Driffill J (1988) Centralization of wage bargaining. Econ Policy 6:13–61

Calmfors L, Nymoen R (1990) Real wage adjustment and employment policies in the Nordic countries. Econ Policy 11:398–448

Card D, Krueger AB (1995) Time-series minimum-wage studies: a meta-analysis. Am Econ Rev 85(2):238–243

Card D, Kluve J, Weber A (2010) Active labor market policy evaluations: a meta-analysis. Econ J 120(548):F452–F477

Cazorla SI, Madero D (2007) Efecto de la reforma al sistema de pensiones sobre el mercado laboral en México. Documento de Trabajo 2007-1, CONSAR

Coe DT, Krueger T (1990) Why is unemployment so high at full capacity? The persistence of unemployment, the natural rate and potential output in the Federal Republic of Germany. IMF Working Paper WP/90/101

Coenen G, McAdam P, Straub R (2008) Tax reform and labour-market performance in the euro area. A simulation-based analysis using the New Area-Wide Model. J Econ Dyn Control 32(8):2543–2583

Congressional Budget Office (2008) Options for responding to short-term economic weakness. CBO Paper, Washington, January

Cox-Edwards A (2002) Payroll taxes. Working paper no 132. Center for Research on Economic Development and Policy Reform, Stanford University

Daveri F, Tabellini G (2000) Unemployment and taxes. Do taxes affect the rate of unemployment? Econ Policy 30:48–104

Disney R (2004) Are contributions to public pension programmes a tax on employment? Econ Policy 19:267–311

Dolado JJ, Malo de Molina JL, Zabalza A (1986) Spanish industrial unemployment: some explanatory factors. Economica 53(210(S)):S313–S334

Doménech R, Fernández M, Taguas D (1997) La fiscalidad sobre el trabajo y el desempleo en la OCDE. Papeles de Economía Española 72:178–191

Dye RF (1985) Payroll tax effect on wage growth. Eastern Econ J XI(2): 89–100

Escobedo MI (1991) Un análisis empírico de los efectos finales producidos sobre el empleo industrial por el sistema de financiación de la Seguridad Social española 1975–1983. Investigaciones Económicas XV(1):169–192

Estrada A, Hernando I, López-Salido D (2002) La medición de la NAIRU en la economía española. Moneda y Crédito 215:69–107

European Central Bank (2008) Labour supply and employment in the euro area countries. Developments and challenges. Occasional paper series no 87

European Commission (1994) Growth, competitiveness, and employment. The challenges and ways forward into the 21st century. Brussels

European Commission (2005) The contribution of wage developments to labour market performance. European Economy Special Report no 1/2005

Evers M, de Mooij RA, van Vuuren DJ (2006) What explains the variation in estimates of labour supply elasticities. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper 017/3

Forslund A (1995) Unemployment—is Sweden still different? Swedish Econ Policy Rev 2:15–58

Franz W, Gordon RJ (1993) German and American wage and price dynamics. Differences and common themes. Eur Econ Rev 37(4):719–762

Fuchs VR, Krueger AB, Poterba JM (1998) Economists’ views about parameters, values and policies: survey results in labor and public economics. J Econ Lit XXXVI(3):1387–1423

Fullerton D, Metcalf GE (2002) Tax incidence. In: Auerbach AJ, Feldstein M (eds) Handbook of public economics, vol 4. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 1787–1872

Gordon RJ (1971) Inflation in recessions and recovery. Brook Pap Econ Activity 1:105–166

Griffith R, Harrison R, Macartney G (2006) Product market reforms, labour market institutions and unemployment. CEPR Discussion Paper no 5559

Griffith R, Harrison R, Macartney G (2007) Product market reforms, labour market institutions and unemployment. Econ J 117:C142–C166

Gruber J, Krueger AB (1990) The incidence of mandated employer-provided insurance: lessons from workers’ compensation insurance. NBER working paper no 3557

Gruber J (1994a) The incidence of mandated maternity benefits. Am Econ Rev 84(3):621–641

Gruber J (1994b) Payroll taxation, employer mandates and the labor market: theory, evidence and unanswered questions. Mimeo

Gruber J (1997) The incidence of payroll taxation: evidence from Chile. J Lab Econ 15(3)Part 2:S72–S101

Hamaaki J, Iwamoto Y (2008) A reappraisal of the incidence of employer contributions to social security in Japan. CIRJE-F-569, Faculty of Economics, University of Tokyo

Hamermesh DS (1979) New estimates of the incidence of the payroll tax. South Econ J 45(4):1208–1219

Hamermesh DS (1993) Labor demand. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Holmlund B (1983) Payroll taxes and wage inflation: the Swedish experience. Scand J Econ 85(1):1–15

Honkapohja S, Koskela E (1999) The economic crisis of the 1990s in Finland. Econ Policy 14(29):400–436

Hugues G (1985) Payroll tax incidence, the direct tax burden and the rate of return on state pension contributions in Ireland. The Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin

Jarrell SB, Stanley TD (1990) A meta-analysis of the union-non union wage gap. Ind Labor Relat Rev 44(1):54–67

Kananassou M, Sala H, Salvador PF (2007) Capital accumulation and unemployment: new insights on the Nordic experience. Mimeo

Keane MP (2011) Labor supply and taxes: a survey. J Econ Lit 49(4):961–1075

Knell M, Stix H (2003) How robust are money demand estimations? A meta-analytic approach. Working paper no 81. Oesterreichische Nationalbank

Komamura K, Yamada A (2004) Who bears the burden of social insurance? NBER working paper no 10339

Kugler A, Kugler M (2003) The labour market effects of payroll taxes in a middle-income country: evidence from Colombia. CEPR discussion paper no 4046

Layard R, Nickell SJ, Jackman R (1991) Unemployment, macroeconomic performance and the labour market. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Leibfritz W, Thornton J, Bibbee A (1997) Taxation and economic performance. OECD Economics Department Working Paper no 176

Leuthold JH (1975) The incidence of the payroll tax in the United States. Public Finance Q 3(1):3–13

Levine R, Renelt D (1992) A sensitivity analysis of cross-country growth regressions. Am Econ Rev 82(4):942–963

Ljungvist L, Sargent TJ (2007) Do taxes explain European unemployment? Indivisible labour, human capital, lotteries and saving. CEPR discussion paper no 6196

Longhi S, Nijkamp P, Poot J (2005) A meta-analytic assessment of the effect of immigration on wages. J Econ Surveys 19(3):451–477

Longhi S, Nijkamp P, Poot J (2006) The fallacy of job robbing: a meta-analysis of estimates of the effect of immigration on employment. J Migration Refugee Issues 1(4):131–152

Melguizo A (2009) Quién soporta las cotizaciones sociales empresariales y la fiscalidad laboral? Una panorámica de la literatura empírica. Hacienda Pública Española / Revista de Economía Pública n.188-(1/2009), pp 125–182

Murphy KJ (2007) The impact of unemployment insurance taxes on wages. Labour Econ 14(3):457–484

Muysken J, van Veen T, de Regt E (1999) Does a shift in the tax burden create employment? Appl Econ 31(10):1195–1205

Nickell SJ (2003) Employment and taxes. CESifo working paper no 1109

Nijkamp P, Poot J (2005) The last word on the wage curve? J Econ Surveys 19(3):421–450

Nunziata L (2001) Institutions and wage determination: a multi-country approach. Mimeo, Nuffield College, University of Oxford

OECD (1990) Employer versus employee taxation: the impact on employment. OECD Employment Outlook, pp 157–177. OECD, Paris

OECD (1994) The OECD jobs study. Evidence and explanations. Part II: the adjustment potential of labour market. OECD, Paris

OECD (2007) Financing social protection: the employment effect. OECD Employment Outlook, pp 57–206. OECD, Paris

Ohanian L, Raffo A, Rogerson R (2006) Long-term changes in labor supply and taxes: evidence from OECD countries, 1956–2004. Research working paper 06-16, The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Research Department

Ooghe E, Schokkaert E, Flechet J (2003) The incidence of Social Security contributions: an empirical analysis. Empirica 30(2):81–106

Pehkonen J (1999) Wage formation in Finland, 1960–1994. Finnish Econ Pap 12(2):82–93

Perry GL (1970) Changing labor markets and inflation. Brookings Pap Econ Activity 3:411–448

Pissarides CA (1991) Real wages and unemployment in Australia. Economica 58(229):35–55

Prescott EC (2004) Why do Americans work so much more than Europeans? Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Q Rev 28(1):2–13

Rogerson R (2007a) Structural transformation and the deterioration of European labor market outcomes. NBER working paper no 12889

Rogerson R (2007b) Taxation and market work: is Scandinavia an outlier? NBER working paper no 12890

Sapir A (2006) Globalisation and the reform of European social models. J Common Market Stud 44(2):369–390

Stanley TD (1998) New wine in old bottles: a meta-analysis of Ricardian equivalence. South Econ J 64(3):713–727

Stanley TD, Jarrel SB (1989) Meta-regression analysis: a quantitative method of literature surveys. J Econ Surveys 3(2):161–170

Tachibanaki T, Yokoyama Y (2008) The estimation of the incidence of employer contributions to Social Security in Japan. Jpn Econ Rev 59(1):75–83

Tyrväinen T (1995) Real wage resistance and unemployment: multivariate analysis of cointegrating relations in 10 OECD economies. OECD Jobs Study Working Paper Series no 10

Vaillancourt F, Marceau N (1990) Do general and firm-specific employer payroll taxes have the same incidence? Theory and evidence. Econ Lett 34(2):175–181

Van der Horst A (2003) Structural estimates of equilibrium unemployment in six OECD economies. Working paper no 22. ENEPRI

Vroman W (1974a) Employer payroll tax incidence: empirical tests with cross-country data. Public Finance XXIX(2):184–200

Vroman W (1974b) Employer payroll taxes and money wage behaviour. Appl Econ 6(3):189–204

Weitenberg J (1969) The incidence of Social Security taxes. Public Finance XXIV(2):193–208

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Manuel Balmaseda, Christian Daude, Rafael Doménech, Rodolfo Méndez, Alejandro Neut and Galo Nuño, as well as the two anonymous referees, for their comments to previous versions of the paper. A first version was published in the Working Paper series of the Instituto de Estudios Fiscales (Papel de Trabajo 20/09). The views expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the opinions of their institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Melguizo, Á., González-Páramo, J.M. Who bears labour taxes and social contributions? A meta-analysis approach. SERIEs 4, 247–271 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-012-0091-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-012-0091-x