Abstract

Soil is major reservoir for microbes and harbors a vast microbial diversity. Soil microbiota plays a pivotal role in biogeochemical cycles, bioremediation, and in health and disease states of humans, animals, and plants. It is imperative to understand the microbial signatures which are specific in such an ecosystem to unravel their potential role and impact on environment. During the recent years, exploration of soil microbial communities has been geared up with the advent of advanced sequencing technologies. Introduction of custom-made protocols and optimized procedures have enhanced the accuracy levels along with cost-effectiveness of DNA extraction. Standardization of DNA extraction method from soil microbiota has its own limitations due to different nature of soils and the complexity of ecosystems. Though a few standardized protocols are in usage, huge variations and complexities among the microbial communities frequently suggest the optimization, based on various known and unknown factors. Therefore, a set of four standardized DNA isolation protocols was comparatively analyzed with respect to our custom-made protocol owing to the scientific fact that the same protocol does not hold good for all soil samples. Furthermore, the developed protocol has been successfully applied for the identification of efficient plant-specific Rhizobial stains for five legume plants from the soils of various locations under same geographical region. Out of 40 Badrachalam forest soils, five samples, KPFS36, CHFS17, TPFS33, GVFS06, and GPFS40, one for each of Arachis hypogaea, Vigna radiata, Vigna mungo, Glycine max, and Cicer arietinum plants, were selected, respectively, for the soil DNA extraction. A considerable improvement in the DNA yield was identified using the modified protocol with a yield of 21.08 μg/g providing abundant DNA fragments for further investigation on Rhizobial species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Soil is one of the major reservoirs of biological diversity on the planet having various complex environments. Bacteria, Archaea, and Fungi contribute significantly to this diversity besides the other microorganisms such as Protozoa. It is an established fact that 100,000–1,000,000 different bacterial and archaeal species are present in 1 g of soil (Bates et al. 2011; Curtis and Sloan 2005; Torsvik and Øvreas 2002). Past three decades have witnessed a remarkable trend in microbial taxonomic diversity through the invention of approaches, which have laid unique insights into uncultured microbial communities avoiding inherent biases in traditional culture-based microbiological techniques. The exploration and characterization of microbial community composition was limited and subjected to cultivability of the members in the environment samples (Maron et al. 2011). Contrastingly, the molecular techniques permit the extraction of representatives of nucleic acids from entire microbial communities of environment samples. However, based on the present estimates, not more than 1% of microbes in the environment is explored; this demonstrates the essential role of culture-independent techniques such as microbial DNA-based analysis in revolutionizing the present and future environmental microbiology.

Various techniques that are practiced today include cell extraction (microbial cells recovery from soil matrix before cell lysis), direct lysis, bead beating (Miller et al. 1999; Courtois et al. 2001; Petric et al. 2011) liquid nitrogen grinding (Ranjard et al. 1998), ultrasonication (Picard et al. 1992), hot detergent treatment (Holben 1994), use of strong chaotropic agents such as guanidinium salts (Porteous et al. 1997), and high concentration of lysozyme treatment (Hilger and Myrold 1991) for the extraction of DNA from sediments and soils. Direct lysis yields less DNA causing shearing and fails to remove major impurities and interfering agents such as humic acid, fulvic acid, salts, and metal ions in molecular analysis. Humic substance coextracted with DNA due to their physicochemical analogy with the nucleic acids (Zhou et al. 1996). Humic acid contamination restrains the activity of Taq DNA polymerase during PCR amplification of genes. Rigorous purification of samples may sometimes cause the loss of DNA density.

Multiple purification methods have been evolved to confiscate humic acid from soil DNA. This includes the use of polyvinyl polypyrrolidone (PVPP; Frostegård et al. 1999), hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB; Zhou et al. 1996), cesium chloride density gradients (Holben et al. 1998, 17), various gel filtration resins (Jackson et al. 1997; Miller 2001), and ion exchange (Tebbe and Vahjen 1993) and size-exclusion chromatography (Braid et al. 2003). Considering a range of soils demonstrated, the usage of PVPP and CTAB might be unreliable option to remove inhibitors (Braid et al. 2003). Therefore, further effective purification of nucleic acids from all soils probably needs several different purification strategies. However, if the concentration of target gene or organism constitutes traces or small portion of microbial community, further purification needs to be balanced against considerable loss of targeted genetic material (Chandler et al. 1997).

The usage of commercial kits to avoid the risk is in wide practice because of the fact that a few methods of DNA extraction using these additional steps might make the process expensive or sometimes impractical while processing a large number of samples (De Lipthay et al. 2004; Ning et al. 2009). Therefore, the current challenge is to develop a standardized protocol for obtaining optimum amount of DNA yield from soils of various types. Even though several researchers described the DNA extraction procedure from forest soil samples, none of them have been found to be robust and adopted by the scientific community unanimously. As the evolution persists, more and more strategic molecular techniques are awaited for simplifying the complexity of molecular biology.

In the present study, four standardized DNA extraction methods were used to extract DNA directly from soil and the efficiency of these methods was assessed by the total yield of DNA. These results helped us in estimating the accurate amount of DNA in each of the five samples and further investigating on targeted Rhizobial species.

Materials and methods

Soil sample collection

Forty soil samples from different locations of Bahdrachalam forest (Telangana State, India) were collected. Four volumes were collected in an equidistance of a square meter from a location, mixed well to make a homogenous mixture, considered as one sample.

Seed selection

Arachis hypogaea, Vigna radiate, Vigna mungo, Glycine max, and Cicer arietinum seeds were collected from the seed testing laboratory of Prof. Jaya Shankar Agriculture University (Telangana State, India). All the seeds belong to same batch and are recommended for plantation.

Microcosm experiment

All the soil samples were collected in pots and are maintained under shade net throughout the life cycle of the plants. All the 40 soil samples are arranged in five pots each and are planted with Arachis hypogaea, Vigna radiate, Vigna mungo, Glycine max, and Cicer arietinum. Before plantation, all the seeds are saturated in water to ensure uniform germination. This avoids the conflict of germination capacity on plant growth, preventing the bias in the assessment of microbial contribution.

Soil selection for DNA isolation

Out of 40, five best growth supporting samples 1 from each plant variety, are selected for further soil DNA extraction to explore the Rhizobium species that contribute for nodulation and thus promote plant growth.

Soil DNA isolation

For the extraction of DNA from soil samples, we adopted four different standardized protocols as outlined below.

DNA extraction methods

Four DNA extraction methods, along with our standardized protocol, were evaluated in this study with respect to the quantity and purity of extracted DNA using five types of rhizosphere soils. Four different Protocols, protocol 1 (Sharma et al. 2007), protocol 2 (Islam et al. 2012), protocol 3 (Fatima et al. 2014), and protocol 4 (Avinash et al. 2016), were compared for obtaining DNA with good yield and purity. Soil samples selected for DNA extractions were immediately placed on dry ice, mixed, and then stored at −20 °C prior to DNA extraction.

Optimized protocol

Heterogeneous DNA was isolated from five soil samples using improved standardized protocol. Finely sieved soil (3 g) was taken for DNA extraction with 6 ml of extraction buffer (100 mM Tris–Cl pH 8.0, 100 mM sodium, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, and 1.5 M NaCl) in falcon tubes (BD Biosciences, CA, USA). After proper mixing, 13 μl of proteinase K (10 mg/ml) was added and then incubated horizontally at 37 °C for 30 min on a platform shaker. After incubation, 750 μl of 20% SDS was added and further incubated at 65 °C for 90 min. For proper extraction of DNA present in soil microbes, all the tubes were frozen in liquid nitrogen (LN2) for 1 min and immediately thawed at 65 °C for 90 min; freeze thaw cycles were performed thrice to improve the efficiency of DNA isolation. The samples were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min; supernatant was collected in a fresh tube and the entire process of lysis and freeze thawing was repeated with the pellet to minimize the loss of DNA. Half in the total volume of supernatant was added with 30% Poly Ethylene Glycol (PEG): 1.6 M NaCl was added in 1:1 ratio and incubated for 2 h at room temperature.

The samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min; aqueous layer was collected in fresh tube and equal volumes of phenol, chloroform, and isoamylalcohol (Merk Millipore) in 25:24:1 ratio was added. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min; supernatant was collected and equal volumes of chloroform and isoamyl alcohol in 24:1 was added. Samples were mixed by gentle inversion and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. A 200 μl pipette tip was cut at the edge to avoid shearing of DNA and the top most layer was collected into a fresh tube. To the samples, 0.6th volumes of chilled absolute isopropanol was added, vortexed, and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min, supernatant was discarded and the pellet was air-dried to remove the traces of isopropanol. Pellet was dissolved in 50 μl of sterile TE buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0). The remnants of RNA contamination was removed by the addition of heat-treated pancreatic RNase A (0.2 μg/μl) followed by incubation at 37 °C for 2 h. Post incubation, the DNA was purified by ethanol precipitation. The supernatant was removed and the DNA pellet was air-dried completely before dissolving it in 50 μl of TE buffer and stored at −20 °C for further use. The quality and quantity of DNA was estimated by agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometer, respectively.

DNA isolation protocol 1

The isolation of DNA was performed as outlined by Sharma et al. (2007). Finely sieved 3 g of soil sample was taken;3.9 ml of extraction buffer (Tris–HCl-100 mM, EDTA-100 mM, NaCl-1.5 M, Sodium phosphate-100 mM, CTAB-1% at pH-8.0) was added and mixed thoroughly. To the samples, 39 μl of proteinase K (10 mg/ml) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min. After incubation, 480 μl of 20% SDS was added to the samples, which were Vortex mixed for 30 s and incubated for 2 h at 60 °C by intermittent mixing at every 15 min interval. Samples were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min, supernatant was collected in a fresh tube, and the pellet was repeated with the aforementioned process for three times to avoid loss of DNA. Collected supernatants were mixed with equal quantity of chloroform and isoamyl alcohol (24:1), gently invert-mixed the tubes, and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min. Aqueous layer was collected, 0.6th volume of isopropanol was added, mixed gently, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. Supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and air-dried at room temperature to remove the traces. The pellet was dissolved in 50 μl of sterile TE buffer and stored at −20 °C for future use.

DNA isolation protocol 2

DNA extraction was performed using protocol explained by Islam et al. (2012). 3 g of sieved soil samples was mixed with 6 ml of 120 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) and incubated on platform shaker at 150 rpm for 15 min. The samples were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min, supernatant was discarded, and pellet was washed with PBS. To the samples, 6 ml lysis buffer solution I (Nacl-0.15 M, disodium EDTA-0.1 M at pH 8.0) containing 15 mg/ml of lysozyme was added and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h by intermittent mixing. To the same samples Lysis solution II (Tris–HCl-0.5 M, NaCl-0.1 M, SDS-10%, pH 8.0) was added and freeze thawed the tubes for three times at −20 and 65 °C respectively for the complete extraction of DNA from microbial cells. The samples were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 15 min, supernatant was collected, and equal volumes of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1) were added. The samples were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min and the aqueous layer was carefully collected. Further, 0.6% v/v isopropanol was added, incubated at room temperature for 1 h, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min. The topmost layer was collected and washed with 70% ethanol, and air-dried the pellet at room temperature. The pellet was re-suspended in 50 μl of autoclaved TE buffer and stored at −20 °C for future use.

DNA isolation protocol 3

The isolation of DNA protocol was performed as described by Avinash et al. (2016). Finely sieved 3 g of soil sample was mixed with 50 ml of cell extraction buffer (NaCl-1 M, PEG 8000-1% (w/v) at pH 9.2), vortex mixed for 30 s and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. Supernatant was discarded; to the pellet, 30 ml of extraction buffer was added and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 20 min at room temperature. The pellet was re-suspended in 500 μl of suspension buffer (Tris–HCl-10 mM, Sucrose-10%, EDTA-50 mM, Nacl-50 nM at pH 8.0), 50 μl of freshly prepared lysozyme (20 mg/ml) was added to it, and incubated at room temperature for 45 min. To the samples 12.5 μl of proteinase K was added and incubated at 55 °C for 45 min. After incubation, 50 μl of 20% SDS was added and incubated with intermittent mixing at 65 °C for 45 min. The samples were then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 5 min at 20 °C; supernatant (S1) was collected in a fresh tube (kept aside); to the pellet, 200 μl of suspension buffer, 50 μl of 20% SDS, and 1.5 mm size glass beads were added. The tubes were vortex mixed for 3 min and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 5 min at 20 °C, and the supernatant (S2) was collected. Sample S2 was mixed with S1 and 10 μl of RNase A (10 mg/ml) was added, and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min; 0.35th volume of 2.5 M potassium acetate (pH 8.0) was added and the tubes were centrifuged twice, at lower (7000 rpm) and higher speed (15,000 rpm), each time at 20 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was collected, an equal volume of isopropanol was added, and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm at 4 °C for 20 min. Supernatant was discarded and the DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried at 55 °C for 10 min. The pellet was re-suspended in 50 μl of autoclaved TE buffer and stored at −20 °C for further use.

DNA isolation protocol 4

DNA was extracted as described by Fatima et al. (2014). 3 g of soil samples was ground using liquid nitrogen and transferred into eppendorf tubes, 45 ml of 120 mM phosphate buffer saline (PBS) was added and mixed thoroughly to incubate at 4 °C on platform shaker. After incubation, all the samples were centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded; to the pellet, PBS was added to repeat the aforementioned step and re-suspended the pellet in 90 ml of DNA extraction buffer (Tris–HCl-1 M, NaCl-5 M, EDTA-0.5 M, CTAB-10%, SDS-10%, and mannitol-0.2 M, at pH 8.0), and incubated at 65 °C for 1 h by intermittent vortex mixing. After incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min and transferred the supernatant into fresh tube. To the supernatant, 150 μL of 5 M NaCl and 150 μL of 10% CTAB were added and incubated at 4 °C for 15 min. After incubation, equal volumes of PCI were added and centrifuged the tubes at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min. Aqueous layer was collected and, 1/10th volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and two volumes of ethanol were added, and incubated at 4 °C overnight for precipitation. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 65 °C for 10 min, supernatant was discarded, pellet was air-dried, and the pellet was dissolved in 50 μl of TE buffer and stored at −20 °C till its further use.

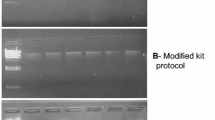

Evaluation of DNA quality and quantity

The sample was subjected to spectrophotometer and agarose gel electrophoresis for the post-DNA isolation analysis. Spectrophotometer enables us to estimate the humic acid content that co-exists with the nucleic acid. The quantity of DNA was analyzed by calculating the A260/A280 ratios described by Sambrook et al. (1989), according to which the humic acid is absorbed at 230 nm; DNA at 260 and protein at 280 nm. The ratio of A260/A230 was found to be 2.30 and that of A260/A280, 1.98. The standard ratios of pure samples were 1.80 (A260/A280 for DNA) and 2.00 (A260/A230 for humic acid; Sambrook et al. 1989). The samples were assessed by comparing the samples with known concentration of molecular weight marker on 0.8% agarose gel-containing ethidium bromide, followed by visualization of gel images under UV-transilluminator (Fig. 1).

Results and discussion

Several methods have been reported down the line for the purification of metagenomic DNA, which seems comparatively expensive. Though the present protocol of isolating DNA requires little longer time, it yielded better quality and quantity of DNA when compared to other protocols. Moreover, limited number of reagents’ usage made it less expensive.

To ensure the proportional accuracy in DNA yield, the quantity of all the samples used in different protocols was maintained constant (3 g). In the protocol 1 (Sharma et al. 2007), 3.9 ml of extraction buffer followed by 480 μl of 20% SDS has been used, unlike in the case of remaining protocols, making it an efficient method next to the present optimized protocol (Tables 1, 2). This is inferred by the increased quantity of DNA yield in almost all the soil samples (Table 3). Though SDS and extraction buffer have been used in protocol 1 and 3, respectively, the effect seems to be limited in the quantification of DNA. The protocol 3 could not extract much DNA than protocol 2 and 4, despite the addition of cell extraction buffer, which basically creates hydrophobic environment and negative charge to the nucleic acids from initial stage of isolation process. A comparative high yield of DNA was recorded with the optimized protocol among the aforesaid standard protocols. Moreover, the protocol has proved to be the efficient, as it has yielded comparatively high volumes of DNA over other four protocols; isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) played a crucial role in separating the proteins and lipids from nucleic acids. This step, though is conventional, purifies the nucleic acids from the other impurities and could be considered as the characteristic step of this protocol. No other protocols in the present study involved purification step by phenol, subsequently inferring a comparatively low yield. In protocol 1 (Sharma et al. 2007), commercial Q Sepharose was used to further purify DNA from contaminants, whereas a conventional (phenol chloroform, isoamyl alcohol) step was performed, making the process less expensive.

The present method includes gentle freeze thawing, optimized incubation time, and temperature. Shearing of DNA negatively affects molecular techniques; therefore, in the present method, cut tips were used to reduce the shearing of DNA. Furthermore, we used phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol in the ratio of 25:24:1 to separate nucleic acids from proteins. In addition, we used PEG to provide hydrophobic environment in buffer. This method potentially had shown its efficacy by considerably increasing the DNA yield in soil sample TPFS33, which reported less DNA yield among all soil samples with the aforesaid four protocols (Table 4).

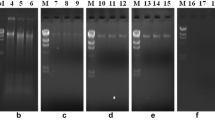

The clear band in gel for optimized protocol (Fig. 1) depicts the genomic DNA that is sufficiently pure and unsheared for further molecular studies. Comparatively, less clear band was observed in protocol 2, suggesting that it is the second best protocol. Band intensity for protocol 1 is comparatively less. Moderate band intensity was reported in protocol 3 and 4, indicating a moderate DNA yield. Extracted DNA by optimized protocol was adequate for further analysis by amplifying with 16S rRNA (Fig. 2) and digestion with Bam H1 restriction enzyme (Fig. 3) to ensure the purity.

This optimized protocol has been experimented at various concentrations from 1X to 6X and the results were observed as shown in Table 2. The efficiency of protocol was found to be optimized at 5X, suggesting it for the rapid application. Interestingly, this optimized protocol was working better comparatively with increased levels of DNA yield in all the five soil samples. The present protocol, which was optimized single sample centric, was working efficient with the other soil samples, suggesting it for wide application.

This may be because of the fact that all soil samples were collected from same forest, that too, from single geographic location. Geographical acclimatization may be a common factor that worked in this particular case. We may hope that the method could be adopted for other geographical forest samples; nevertheless, the specificity and other scientific parameters should be considered. However, it is not certain that the method will yield increased levels of DNA in all experiments with all samples.

Conclusion

In the present optimized protocol, we have used a combination of conventional, mechanical, and enzymatic methods for isolation of contamination-free and improved quantity of DNA, which is efficient for further molecular studies such as metagenomic library construction. To the best of our knowledge, the present optimized protocol, in combination of modern technology and conventional methodology (enzymatic break down, freeze thawing, and phenol isolation), yielded good quantity of DNA without contamination of humic acid from different habitats of soils. The DNA was unsheared and of better quality, because we used cut tips to avoid mechanical forces for the scattered nucleic acid. In molecular biology for better interpretation of results, always pure DNA samples, preferably free from other salts and nucleases, are used. Enzymatic addition enabled protease, RNase removal, and PEG provided hydrophobic environment from salts. Also, the optimized incubation time and temperatures ensured favorable atmosphere for all the reagents to complete the reaction. Therefore, we inferred that the present optimized protocol could be adopted for the preliminary conformation of microbial communities in bulk soil samples, especially forest soils (to make the process less expensive) where the microbial distribution among the forest locations are taken into consideration, for further molecular studies.

References

Avinash N, Kunal J, Shah AR, Madamwar D (2016) An efficient and cost-effective method for DNA extraction from athalassohaline soil using a newly formulated cell extraction buffer. 3 Biotech 6(1):62. doi:10.1007/s13205-016-0383-0

Bates ST, Berg-Lyons D, Caporaso JG, Walters WA, Knight R, Fierer N (2011) Examining the global distribution of dominant archaeal populations in soil. ISME J 5(5):908–917. doi:10.1038/ismej.2010.171

Braid MD, Daniels LM, Kitts CL (2003) Removal of PCR inhibitors from soil DNA by chemical flocculation. J Microbiol Methods 52(3):389–393

Chandler DP, Schreckhise RW, Smith JL, Bolton H Jr (1997) Electroelution to remove humic compounds from soil DNA and RNA extracts. J Microbiol Methods 28:11–19

Courtois S, Frostegard A, Goransson P, Depret G, Jeannin P, Simonet P (2001) Quantification of bacterial subgroups in soil: comparison of DNA extracted directly from soil or from cells previously released by density gradient centrifugation. Environ Microbiol 3(7):431–439

Curtis TP, Sloan WT (2005) Exploring microbial diversity—a vast below. Science 309(5739):1331–1333

De Lipthay JR, Enzinger C, Johnsen K, Aamand J, Sorensen SJ (2004) Impact of DNA extraction method on bacterial community composition measured by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Soil Biol Biochem 36:1607–1614

Fatima F, Pathak N, Rastogi Verma S (2014) An improved method for soil DNA extraction to study the microbial assortment within rhizospheric region. Mol Biol Int 2014: Article ID 518960, pp 1–6. doi:10.1155/2014/518960

Frostegård A, Courtois S, Ramisse V, Clerc S, Bernillon D, Le Gall F et al (1999) Quantification of bias related to the extraction of DNA directly from soils. Appl Environ Microbiol 65(12):5409–5420

Hilger AB, Myrold DD (1991) Method for extraction of Frankia DNA from soil. Agric Ecosyst Environ 34:107–113

Holben WE (1994) Isolation and purification of bacterial DNA from soil. In: Weaver RW et al (eds) Methods of soil analysis, part 2. Microbiological and biochemical properties, vol 5. Soil Science Society of America Inc, Madison, pp 727–751

Holben WE, Jansson JK, Chelm BK, Tiedje JM (1998) DNA probe method for the detection of specific microorganisms in the soil bacterial community. Appl Environ Microbiol 54(3):703–711

Islam MR, Sultana T, Melvin Joe M, Cho JC, Sa T (2012) Comparisons of direct extraction methods of microbial DNA from different paddy soils. Saudi J Biol Sci 19(3):337–342. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2012.04.001

Jackson CR, Harper JP, Willoughby D, Roden EE, Churchill PF (1997) A simple, efficient method for the separation of humic substances and DNA from environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 63(12):4993–4995

Maron PA, Mougel C, Ranjard L (2011) Soil microbial diversity: methodological strategy, spatial overview and functional interest. C R Biol 334(5–6):403–411. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2010.12.003

Miller DN (2001) Evaluation of gel filtration resins for the removal of PCR-inhibitory substances from soils and sediments. J Microbiol Methods 44(1):49–58

Miller DN, Bryant JE, Madsen EL, Ghiorse WC (1999) Evaluation and optimization of DNA extraction and purification procedures for soil and sediment samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 65(11):4715–4724

Ning J, Liebich J, Kästner M, Zhou J, Schäffer A, Burauel P (2009) Different influences of DNA purity indices and quantity on PCR-based DGGE and functional gene microarray in soil microbial community study. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 82(5):983–993. doi:10.1007/s00253-009-1912-0

Petric I, Philippot L, Abbate C, Bispo A, Chesnot T, HallinS Lavel K et al (2011) Inter-laboratory evolution of the ISO standard 11063 “Soil quality-Method to directly extract DNA from soil samples”. J Microbiol Methods 84(3):454–460. doi:10.1016/j.mimet.2011.01.016

Picard C, Ponsonnet C, Paget E, Nesme X, Simonet P (1992) Detection and enumeration of bacteria in soil by direct DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol 58(9):2717–2722

Porteous LA, Seidler RJ, Watrud LS (1997) An improved method for purifying DNA from soil for polymerase chain reaction amplification and molecular ecology applications. Mol Ecol 6:787–791

Ranjard L, Poly F, Combrisson J, Richaume A, Nazaret S (1998) A single procedure to recover DNA from the surface or inside aggregates and in various size fractions of soil suitable for PCR based assays of bacterial communities. Eur J Soil Biol 34:89–97

Sambrook J, Fritschi EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular cloning: a laboratorymanual. Spring, New York

Sharma PK, Capalash N, Kaur J (2007) An improved method for single step purification of metagenomic DNA. Mol Biotechnol 36(1):61–63

Tebbe CC, Vahjen W (1993) Interference of humic acids and DNA extracted directly from soil in detection and transformation of recombinant DNA from bacteria and a yeast. Appl Environ Microbiol 59(8):2657–2665

Torsvik V, Øvreas L (2002) Microbial diversity and function in soil: from genes to ecosystems. Curr Opin Microbiol 5(3):240–245

Zhou J, Bruns MA, Tiedje JM (1996) DNA recovery from soils of diverse composition. Appl Environ Microbiol 62(2):316–322

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Dr. K. Srinivasulu, Head, Dept of Biotechnology, KL University for his support in research. Express gratitude to Dr. Vijaya Saradhi for his moral support and inspiration. Special thanks to Sirisha Jeereddy for her support in formatting and data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Satyanarayana, S.D.V., Krishna, M.S.R. & Kumar, P.P. Optimization of high-yielding protocol for DNA extraction from the forest rhizosphere microbes. 3 Biotech 7, 91 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0737-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0737-2