Abstract

Coal seams, particularly deep unmineable coal reservoirs, are the most important geological desirable formations to store CO2 for mitigating the emissions of greenhouse gas. An advantage of this process is that a huge quantity of CO2 can be sequestrated and stored at relatively low pressure, which will reduce the amount of storage cost required for creating additional platform to store it. The study on CO2 storage in coal seam to enhance coal bed methane (ECBM) recovery has drawn a lot of attention for its worldwide suitability and acceptability and has been conducted since two decades in many coalmines. This article focuses on the coal seam properties related to CO2 adsorption/desorption, coal swelling/shrinkage, diffusion, porosity and permeability changes, thermodynamic/thermochemical process, flue gas injection, etc. Here, the performance analysis of both CO2 storage and ECBM recovery process in coal matrixes is investigated based on the numerical simulation. In this study, a one-dimensional mathematical model of defining mass balances is used to interpret the gas flow and the gas sorption and describe a geomechanical relationship for determining the porosity and the permeability alteration at the time of gas injection. Vital insights are inspected by considering the relevant gas flow dynamics during the displacement and the influences of coal swelling and shrinkage on the ECBM operation. In particular, pure CO2 causes more displacement that is more efficient in terms of total CH4 recovery, whereas the addition of N2 to the mixture assists to make quicker way of the initial methane recovery. However, this study will support future research aspirants working on the same topic by providing a clear conception and limitation about this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coal seams, particularly those are unmineable and found in deep reservoir, are desirable target formations to store CO2 as a part of mitigating greenhouse gas emission process (Talapatra 2019), because coal can store a large quantity of CO2 gas via adsorption process at relatively high temperature and low pressure, compared with the other target reservoirs, which further reduces both the compression and injection expenses (Reid et al. 1987). This includes also the existing well infrastructure and economic benefits to the enhanced coal bed methane (ECBM) recovery operation. Hence, much endeavor has been conducted toward the ECBM recovery studies by focusing on the CO2 injection approach, which is considered as an essential area of carbon capture, utilization, and storage purposes (Talapatra et al. 2019; Busch et al. 2003; Fitzgerald et al. 2005).

The concept of storing CO2 under coal reservoirs for enhancing the coal bed methane recovery criteria has been directed since the early 1990s, which recently have included N2 to make a mixture of flue gas with CO2 to promote the process effectively (Arri et al. 1992). The feasibility researches on the ECBM recovery process initially investigate the difference between CO2 and CH4 based on the pure gas adsorption behavior and competitive adsorption behavior, followed by researches on the permeability alteration characteristics due to the variation in CO2 and CH4 adsorption/desorption-induced coal swelling/shrinkage (Godec et al. 2014; Fujioka et al. 2010). According to Connell et al. (2011) simulation approach on CO2 injection can be designed by performing a core-flooding experiment, whereas modeling studies represent the permeability behavior at the time of ECBM recovery operation. In fact, laboratory analysis and experiments can give a simple overview about the ECBM process, though the practical conditions in field test are very complex to investigate (Mavor et al. 2004). Therefore, a number of field tests have been done to examine the suitability of CO2 storage facilities and ECBM behavior in parallel with the laboratory experiments based on the practical-field conditions.

Amoco carried out the first field test on the reality of initiating ECBM recovery with CO2 injection in December 1993, in the San Juan Basin of Colorado, which was further validated by Meridian, conducted in the same basin in 1995. However, those studies could not provide any satisfied results enough to establish this project under wide variety of field conditions. A field trial test on the largest scale CO2 storage was accomplished in San Juan Basin from 1995 to 2001. There, around 335,000 tons of CO2 was pushed into four wells, with the large value of CO2 injection rate to facilitate the high permeability of coal seams. Afterward, more than a dozen of field trials on ECBM test have been orchestrated in low-permeability coal seams at minor scale across the world (Michaeel et al. 1993).

Recently, ECBM has been reviewed and inspected with much effort, since it is considered as a vital research topic in the area of CO2 capture and sequestration technology. The main factors looked at the initial comprehensive review were related to the coal properties and the coal storage capacity of ECBM recovery (Connell et al. 2014; Sams et al. 2005). Mazzotti et al. (2009) provided a short review about the key technical aspects and chemical engineering phenomena of ECBM operation such as adsorption/desorption process, swelling/shrinkage process, permeability alternation, etc. Previous studies only focused on the reservoir simulation modeling relevant to the flow theory and dynamic permeability loss. On the contrary, recent studies more likely focus on the injection program to increase the correlation between the CBM production and ECBM recovery operation. For example, Pan and Connell (2012) investigated the coal permeability modeling in reservoir, where Bush and Gensterblum (2011) reviewed the gas adsorption/desorption related to the both CBM and ECBM processes, in which field data of ECBM test were used as permeability modeling testing.

In upcoming decades, natural gas keeps a great contribution to the energy distribution and utilization sectors not only for its huge availability, but also for its low carbon content comparing with oil or other fossil fuels (Gale 2004). At the same time, the need of focusing on the technology to capture produced carbon dioxide from the atmosphere along with storing the gas safely for allowing the continued uses of fossil fuels is also an important task. This will decrease the harmful influences of carbon dioxide gas on the existing climate by providing safe storage locations. Moreover, the method of ECBM recovery by injecting flue gas into the coal seams may be a striking alternative way for increasing the production of gas considerably. This flue gas can be collected in a pure state in different ways. The flue gas is considered as an exhausted gas produced by the combustion of fuels from the power plants and may result into straightly injected, thus eliminating the most expensive capturing stages (Viete and Ranjith 2006). The flue gas is generally composed of majorly nitrogen gas (87%) and minimally carbon dioxide gas (13%). However, the adsorbent power of N2 is very weak with respect to the CO2; still it helps to keep up the permeability of coal seams sufficiently high. Therefore, it is mandatory to compress the N2 gas along with the CO2 gas for eliminating this drawback prior to injection.

After observing the evidences from performing some field tests, it has come to the decision that the interacting relationships between the coal and the gas have to analyze better if ECBM recovery process needs to be amplified at a commercial scale. The phenomena of gas sorption and swelling capacity have intricate influences on the displacement dynamics. The exact interpretation of these phenomena is absolutely important for the development of plausible used reservoir simulating parameters to assimilate the history data acquired from ECBM production well (Mazumder et al. 2006). The input parameters used for these studies have looked on to the several aspects of the method of injecting CO2 into the coal beds, such as gas sorption, gas swelling, permeability changes based on the gas injection types, etc.

The principal factors and mechanisms have been shown in this study by providing one-dimensional models that influence the ECBM recovery and CO2 storage processes. To make this study so understandable, the pores of coal seams are divided into 4 types of region (Mazzotti et al. 2009; Li and Fang 2014). First one is cleats, a natural fracture system in the surface of the coal seam where both water and gas are presented, and second one is known as micropores where the phenomena of adsorption occur. The rest two pores are defined as macropores and mesopores where free gas can only be found. The ordinary assumption of injecting CO2 to displace the CH4 gas is not resulted to only one step; rather, it is consisted of multistep procedures. The flue gas that infused to the coal seams can diffuse to reach the inner surface of the coal bed from the fracture network over the macropores and matrix. Here, the exchange of gas takes place by forcing to create desorption phase and lowering the gas adsorption-induced partial pressure. Finally, at the time of flowing to the production well, the desorbed gas again needs to diffuse from the macropores and matrix to the outer fracture network. The criteria of this type of mass transfer can be interpreted by employing a linear driving force equation with applying a single mass transfer factor or a corresponding time constant, in the various kinds pore (Cui et al. 2007).

In previous studies, few models were derived to represent this simple phenomenon of mass transfer by describing the interaction of porosity and permeability alternations in the coal beds during the gas injection. Those models were successfully employed to interpret the experiments on pure CO2 injection into coal seams under the simulated reservoir pressure and temperature conditions, particularly confined under an outer hydrostatic force per area of the cores.

In this work, those studies are slightly stretched more to show the multi-component single-phase displacement of gas in a coal bed and measure the CO2 storage performance in ECBM recovery process in the coal cores. Here, especially, the injection of flue gas mixtures into a coal bed including the various scenarios of ECBM operation with various concentrations of pure N2 and pure CO2 gases is investigated that remained saturated initially with methane (Oudinot et al. 2011; Pan and Connell 2007). Besides this, more efforts will be placed on the influences of sorption-simulated swelling on the coal permeability and on its effect on the operation of CO2 gas storage itself.

Coal composition and coal ranks

Coal seam, a three-dimensional particle, has been consisted through the biodegradation of plant materials by the imposition of high pressure and temperature over millions of years, which is a mixture of organic ingredients and inorganic minerals. This advanced transformation of coal mass is referred to as coalification process. According to the level of coalification process, the coal is segmented into various ranks by measuring the quantity of carbon content contained in it, as increasing carbon content increases coal rank. Coal is fundamentally of two kinds according to the carbon content: low and high. The low-rank coal is subdivided into sub-bituminous and lignite coal, where high-rank coal is similarly subdivided into anthracite and bituminous coal (Pan and Connell 2007; Shao et al. 2012). Table 1 shows the sort out of various ranks of coal based on their coal’s composition, including its water content, carbon content, and volatile matter. From this table, one can know about the strength, permeability, porosity, and adsorption capacity to measure the degree of pore space for fluid movement and the flowability of fluid through the porous medium. A number of prevalent physical properties of the coal seam, such as in situ pressure and temperature, depth, rank, moisture content, and fracture concentration, play a great role in transport mechanism in the coal mass.

The amount of contained gas formed during the coalification process in each coal seam is different, including approximately 90% of methane with minor quantities of other wet elements like ethane and butane. The application of subsequently enhancing pressure during the coalification process accounts for the trapping of this naturally produced methane in the coal seam, and it occasionally adsorbs into the micropores through the cleats (Masoudian et al. 2013; White et al. 2005). The pressure induced surrounding the saturated rock layer is called hydrostatic pressure, and this pressure is so important to hold the adsorbed methane inside the coal mass. However, these things have made coal bed methane a pure gas compared to the other conventionally produced petroleum fuels.

CBM production process

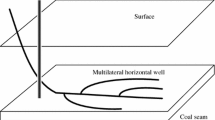

A large amount of CH4 gas is stored in coal matrixes through the adsorption process at greater pore fluid pressure. As a result, when the pore pressure reduces to cause the desorption process to desorb this stored CH4 gas, the CH4 gas can be continuously produced. To reduce the pore fluid pressure, first naturally remaining pore water is pumped out through a drilled well and then along with the coal seams which are considered as a combination of horizontal bore holes and vertical wells (Scott 2002). Initially this type of well system will release pore water and then begins to desorb and release CH4 gas through the well, which is illustrated in Fig. 1. After that, the following produced gas is obtained from the surface, which is further sequestrated from the other components and sent for utilizing as a fuel source.

Coal seam gas production process (created by the author using data from Rice and Nuccio 2000)

Figure 2 shows the three production stages through which the CBM well must need to go for producing the CH4 gas. Now in the first stage, a large amount of pore water has to be pumped out from the production well to decline the reservoir pore pressure, which is also known as dewatering stage. In this dewatering stage, the methane production is not significant than the water production, though the rate of methane production subsequently increases with proceeding time compared to the water production. The methane production remains almost stable in the second stage along with the continuous decreases in water production rate (Bae, and Bhatia 2006). However, when the water production rate becomes negligible, then CH4 production again starts to decrease in the final stage until it becomes uneconomical to continue. This entire period including methane production is known as the economic lifetime for a coal seam. The length of the total economic lifetime is assumed around 100 years at recent rate of production for any coal seams in the worldwide (Perera and Ranjith 2015).

Production stages in a typical CBM recovery process (created by the author using data from Rice and Nuccio 2000)

Though the production technique of conventional CBM production operation seems very simple, still it can create many issues involving in production of water and few types of environmental disasters (Pini et al. 2009). Since deep coal beds are usually remained in saturated condition, it is important to remove thousands to millions gallons of polluted water from a single well each day to decline the pore water pressure for obtaining the maximum CH4 desorption pressure inside the coal seam. For example, according to Thomas and Beatie (2001), approximately 17,000 to 22,000 gallons of water was pumped out each day during the initial years of production from a CBM production well in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin in the USA. In fact, this type of dewatering process in large amount causes significant depletion in ground water table involving in many environmental issues, but these concerns are not playing as drawbacks to this operation nowadays.

However, the CBM water is considered as a highly saline water and sometimes it likes to get mixed with ground water to make it also a saline water, which further causes to contaminate the ground water used for both drinking and agriculture purposes (Chen et al. 2010). It is obtained from the previous studies that the total dissolved solid (TDS) concentrations in the water released approximately from 1100 to 12,500 mg/L during the CBM exploration, whereas the normal (TDS) of sea water and good-quality drinking water are close to 35,000 mg/L and 500 mg/L, respectively. (TDS level is a term used to estimate the amount of salinity.)

Besides these, there is another crucial issue related to the extensive required time during coal seam gas recovery operation to reach the initial production of CH4 gas, since it is essential to release huge amount pore water from the production wells (Vishal et al. 2013). This dewatering process affects the coal permeability during the CBM production, which in turn influences the coal structure (shrinking, hardening, and strengthening) and causes less harvesting of gas with time. In addition, declination of seam’s pore pressure surrounding the rock masses causes to increase the external lithostatic pressure acting on the coal seams, which further reduces the porosity of the coal seams. Hence, the intention of increasing coal seam gas recovery by employing the conventional pressure depletion technique is commercially so ineffective for the production of CH4 from many drilled wells. For instance, according to Gale and Freund (2001), conventionally used pressure depletion technique cannot be able to recover more than 50% of the gas in place, since it includes uneconomical greater pressure depletion (approximately 75–85%). This is the main reason behind the remaining of methane gas in the seam in large amount after the completion of operating techniques.

After highlighting all the issues and facts related to the using of current strategies, it becomes vital to search for new updated operational technologies to enhance the CBM recovery operation by eliminating the serious drawbacks involving with the pressure depletion method in reservoir. Those techniques will make the ECBM recovery operation more economical and safer from the previous conventional ways.

Modeling

The conferred assumptions are considered during the development of the model:

The system’s conditions are assumed in isothermal state to explore the adsorption kinetics of carbon dioxide in coal seam. This is very crucial for understanding the dynamic response of coal to carbon dioxide sorption under various equilibrium pressures.

All the physicochemical and mechanical variables are constant and uniformly distributed. These variables have the possibility to change the coal seam structures by affecting the stress state of overlying rock strata. Variation of mechanical properties of coal seam can lead to create problems during the measurement of the integrity and safety of storage scheme under storage conditions.

The behavior of coal in a linear poroelastic medium is isotropic. The mathematical approach in poroelastic medium could be more useful than the conventional elastic medium in cases of fluid content that can move within the pore space.

The flow of gas is considered in single phase for the Darcy’s law, as water flow is less significant compared to the methane recovery in this study.

Besides these, few assumptions may have to be justified by taking into account the situations where gas injection initiates at the final stage of the so-called initial recovery operation. Actually, the major amount of water originally remained in the reservoir, is removed during the initial recovery operation and the rest fraction of the water is considered immobile undoubtedly (Pini et al. 2011; Pan et al. 2017). The two principal components that form the model are needed for representing the two aspects of the recovery operations. First one is known as mass transfer balances for gas flow and sorption, and the second one is as stress–strain relationship to describe the alternations of porosity and permeability at the time of injection. Here, the model is slightly extended for multi-component single-phase (gas) displacement in a coal seam, where the previous studies have applied this model successfully for interpreting pure gas injection experiments into coal seam.

Mass balances

In fact, coal reservoirs can be considered as a fracture system with high permeable fracture network and low permeable coal matrix. In this work, the overall porosity of the coal is symbolized by \(\varphi_{\text{t}}\), which is further divided into cleat porosity, \(\varphi_{\text{c}}\), and macroporosity, \(\varphi_{\text{p}}\). The microporosity of the coal is being accounted as a part of the solid particle, i.e.,

Both the gas pressure and concentration across the fractures and macropores are set to be constant during the sorption process, as this process is considered as a rate-restricting stage. Material balance for a system of nc components is noted for each component, i:

where ni = adsorbed phase concentration of component, i; ci = actual gas concentration of component, i; u = superficial velocity; t = time coordinate; z = space coordinate.

A pressure gradient of nearly 4 MPa through the coal seams exists for the whole duration of the continuous gas injection operation, where axial dispersion is ignored. Not only that, but also the influence of diffusion in the fractures is negligible under such conditions and assumes that the flow is controlled by convection. The conservative analysis of Peclet number (the ratio of the characteristic time for convection to the characteristic time for diffusion) can help to justify this conclusion and some conditions assumed in this study. Axial mixing can be ignored safely for the value of Peclet number at 600 and a diffusion coefficient of 10−5 m2/s.

A linear driving force equation is applied to interpret the sorption rate of component i through the coal’s matrix, i.e.,

where kmi = the mass transfer coefficient of component, i.

Here, the driving force-initiated gas sorption is the difference between the adsorbed phase concentrations of component in equilibrium state, ni, for component i. The first one is expressed by an equilibrium adsorption isotherm, i.e.,

where \(n_{i}^{*}\) = the adsorbed concentration of component i per unit volume of coal in the solid particle; \(n_{i}^{\infty }\) = saturation capacity per unit mass adsorbent; \(\rho_{s}\) = adsorbed total density; \(y_{i}\) = molar fraction of gas; \(P\) = equilibrium pressure; \(b_{i}\) = equilibrium constant of Langmuir model for component, i.

The superficial velocity u is defined by Darcy’s law as follows:

where \(\mu\) = the dynamic viscosity; \(v\) = the interstitial velocity; \(k\) = the permeability.

Stress–strain relationship

For interpreting the mechanical characteristic of coal seams at the time of injection operation, a stress–strain interactive model is required. The fluid pressure keeps a decisive influence in estimating the stress condition of the reservoir, thus affecting notably the porosity and the permeability of the fracture networks (Cui et al. 2007; Gray 1987).

Initially, the fractures are shut down or extended, depending on whether the effective pressure on the rock is enhanced or belittled. Here, effective pressure is defined as lithostatic overburden minus the fluid pressure. Moreover, the openings of the fracture network are closed when the coal starts swelling upon gas sorption. Now, an equation is written to have the following usual form in the case of coal (Bustin et al. 2008; Durucan and Shi 2009):

where \(p_{c}\) = the lithostatic overburden (confining pressure); s = total swelling; \(c_{1} {\text{and}} c_{2}\) = two constant parameters of coal properties; subscript, 0 = indicates an arbitrary factor elected for initial state.

In this study, the reference magnitudes of porosity and permeability are applied to a non-deformed coal in contact with a non-swelling gas at ambient pressure. It is worth much to mark out that an extreme pressure is confined with high-pressure gas injection operation on coal cores for validation purpose.

Now, a Langmuir-derived model can be effectively interpreted for the coal swelling study, which is further extended in an analogous way for gas sorption mixtures as (Pini et al. 2011; Pan et al. 2017; Durucan and Shi 2009):

where \(s_{i}^{\infty } {\text{and}} b_{i}^{s}\) = the corresponding parameters for isotherm conditions.

An equation indicating the total swelling as a function of gas sorption is derived by combining Eqs. (4) and (7) to maintain the physical relationship between sorption and swelling. However, this derived equation additionally allows the consideration of kinetic phenomena of swelling process and describes the total swelling using the sorption rate provided by Eq. (3) as:

where \(\alpha_{i} {\text{and}} \beta_{i}\) = Langmuir parameters of the sorption and swelling isotherms, i.e.,

Nevertheless, it should be noted that Eq. (8) is only valid for 0 ≤ ni ≥ n∞i.

Solution procedure

The problem is ascertained by Eqs. (1)–(6) and further accomplished by the following fundamental models: (a) the Peng–Robinson equation of state, required to include gas density with temperature and pressure, and (b) an additional relationship for evaluating the gas mixture viscosity using a method of Wilke. Now, the initial conditions along with boundary conditions are written as follows:

Initial conditions: when t = 0, ci = c0i, 0 ≤ z ≤ L

Boundary conditions: when z = 0, ci = cinji, t > 0

Here, the orthogonal layout method has been employed to discretize the PDEs in space. However, the resulting approach of solving ordinary differential equations has been done numerically by applying a commercial ODEs solver (in Fortran).

Parameter estimation

A comprehensive set of experimental data of few previous works has been generated and correlated with referencing to the present study to calculate the sorption and swelling isotherms of CH4, CO2, and N2 that have been fitted using the Langmuir model and delineated in Fig. 3 (Pini et al. 2011; Yamaguchi et al. 2006). Now, a uniform magnitude is assumed for converting the estimated extended sorption isotherms to the absolute sorption isotherms for the adsorbed phase density before initiating fitting work, such as 36.7 mol/L, 42.1 mol/L, and 47.1 mol/L for CO2, CH4, and N2, respectively. The magnitudes of the fitted parameters are provided in Table 2.

Langmuir isotherms a sorption and b swelling at 45 °C as a function of pressure for CH4 (dashed line), CO2 (solid line), and N2 (dotted line) (Yamaguchi et al. 2006)

In principle, based on the particular simplified stress condition of the coal bed, the parameters C1 and C2 in Eq. (6) can be measured upon the mechanical features only. After evaluating the field conditions of coal bed, the relationships for the coefficients of C1 and C2 are provided in Table 3. The two elastic input parameters used in the bulk modulus equation for all applied models, i.e., \(K = E_{y} /\left[ {3\left( {1 - 2v} \right)} \right]\), are defined as Young’s modulus of elasticity \(E_{y}\) and Poisson’s ratio v, respectively. But, in the model for a fracture derived by Shi and Durucan, Ef can be compared with the Young’s modulus, whereas fracture compressibility is defined as Cf (Bustin et al. 2008; Gilman and Beckie 2000). In a resembling way, the additional model derived by Pini et al. is used in an experiment for two purposes. First one is to achieve the values of Ce for non-swelling or non-adsorbing gas, whereas the second one is to obtain the values of Cs for swelling or adsorbing gas. (Further details are explained in the next section.) Finally, the parameters required for the two coefficients in the Peng–Robinson EOS (equation of state) are reported in Table 4.

Model evaluation

A numerical representation for a coal seam underlying at 500 m depth is explained here, in which the applied properties are obtained from Barapukuria Coal Field (Dinajpur, Bangladesh). The input values of the properties for simulation model are synopsized in Tables 5 and 6. The value of coal permeability has been chosen between 1 and 10 mD to match for coal beds. For a sorption time constant \(\tau = 1/k_{\text{mi}}\) of around 1.5 days, a coefficient of mass transfer has been selected at 10−5 s−1, in comply with the parameters applied in reservoir simulation and additionally from the carried out experiments. The production well’s pressure is held uniform at a magnitude of Pout = 0.1 MPa, and the injection pressure at a value of Pinj = 4 MPa is assumed to be slightly minimal than the corresponding hydrostatic pressure of the coal seam at 50 MPa. However, during the initiating moment of injection operation when the CH4 gas is saturated 100%, the reservoir pressure is not higher than the hydrostatic pressure and simply has taken a magnitude of P0 = 1.5 MPa. (The scenario may be different during the coal bed primary production.)

For highlighting the influence of permeability changes on gas the flow dynamics at the time of ECBM process, two cases have been observed, which vary in the magnitude of the constant parameter C2, in Eq. (6). Firstly for “Case A,” to estimate Cs that indicates as the weighted average among the three components, the magnitudes of the parameter Cs,i (for each component i) have been obtained from the experiment, i.e., \(C_{s} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{{n_{c} }} C_{s,i} s_{i}\), where xi denotes for the fractional swelling (si/s) and values of \(C_{s,i}\) held for CH4, CO2, and N2 are 0.624, 1.479, and 2.336, respectively. Now for “Case B,” we will consider it as robust swelling case, that is why the value of \(C_{s,i}\) has been taken four times higher than the previous case for CO2 and also has been set for other components and the value of these given parameters is given in Table 6. To compare the values of these parameters with the values from other studies, they are reported simultaneously with using a likable stress–strain relationship. In addition, it is notable to see that the initial values of porosity used in this study are quite larger than those previous studies. The main reason behind this fact is its difference to referred condition (zero, 0). This condition refers to a state where no fluid pressure or no confinement is presented (unstressed state); on the other hand, this similar thing is defined as initial reservoir condition in the other studies. Thus, the overburden stress can get an opportunity to take into account in this study.

Results

Permeability behavior

The permeability variations can be calculated in analytical approach using Eq. (6) only, when it is assumed that CH4 is thoroughly displaced by the injecting gas. Here, for both Case A and Case B, the obtained changes in permeability upon various injection scenarios (from pure CO2 to pure N2) are shown in Fig. 4. For both cases, the confining pressure has been held uniform at a magnitude of 10 MPa. It has been seen from the figure that primary recovery scheme can compare with the anticipated injection curves (dashed line—pure CH4), in which the coal seam condition prior to initiated gas injection is pointed out with a circle. The coal bed thoroughly loaded with the injected gas at a pressure resembling to the injection pressure during the ending of the ECBM process, where the figure further displays a theoretical abandonment scheme at 4 MPa by placing a vertical dotted line. Though there is no variation between the Case A and Case B, still injection of pure CO2 leads to the robust declination in permeability, whereas a counteracting influence can be seen during the addition of N2 gas to the mixture gas. In fact, the change in the permeability characteristic under several injection criteria depends on the propagation of coal swelling at a constant pressure, which is mostly fluid dependent. However, the injection of CO2/N2 mixtures impels minor permeability declination compared to pure CO2, as the sorption and swelling capability of N2 is very poor compared to CO2 and CH4 (Fig. 3). The value of permeability can be enhanced greatly compared to preliminary condition, when amount of N2 is much in gas mixtures. Moreover, the permeability differences in Case B are more evident from the Case B because of the higher swelling constant (C2). To be specific, the permeability can be either decreased or increased of around one order of value in Case B, depending on whether CO2 or N2 is injected. Now, in complying with the previous studies, it can be inspected that the so-called rebound pressure does not visualize in the pressure range because of attributing stronger swelling for Case B. But, in the context of Case A, a minimum permeability behavior can be clearly seen in the position of existing rebound pressure.

Permeability ratio k/k0 as a function of pressure P under different injection scenarios for a Case A (weak swelling) and b Case B (strong swelling) [solid lines—mixtures of pure CO2 and pure N2 (80:20/CO2:N2, 50:50/CO2:N2), dashed line—corresponds to the primary recovery scenario (pure CH4), empty circle—refers to the initial condition in the reservoir]

In the following, the behavior of permeability just recapitulated has been utilized to the model as an input for presenting the simulations results of ECBM operation. First, a number of ECBM scenarios including the injection of CO2/N2 gas mixtures with various compositions are studied and put for comparing upon the performance of the ECBM/CO2 recovery operation. However, for initiating the investigation on the influence of coal swelling more to clarify, a comparative study has been done between the Case A and Case B.

Influence of injected gas composition

The composition schemes of CO2, CH4, and N2 on the coal seam axis are shown in Fig. 5 for three various injection scenarios: (a) pure CO2, (b) 50:50/CO2:N2, and (c) pure N2. It is observed from this figure that pure N2 can excel the CH4 gas with more speed, when it is injected so smoothly in the displacement front. Not only that, but also it is assigned to the adsorption characteristic of the involving gases, as in this case CH4 gas displacement is higher than the injected N2 adsorption. These both effects resulted from the injection of CO2/N2 gas mixture are appeared in the central figure. The amount of N2 gas is rich in fluid phase at the CO2/CH4 front, though it becomes a minor component in later.

Composition profiles of CH4, CO2, and N2 along the coal seam for three various injection schemes: a pure CO2, b 5050/CO2:N2, and c pure N2 (Pini et al. 2011)

Now, we focus on the production well to interpret the flow rates of CH4, CO2, and N2 under the above-described three scenarios, which are shown in Fig. 6. Due to the behavior of characteristic displacement, breakthrough of CO2 occurs to complete the CH4 recovery process when pure CO2 is injected. On the other hand, the gas mixtures help breakthrough of N2 to take place faster which contains pure N2 gas. But, when the injected mixture contains 50:50/CO2:N2, this produces a stream of CH4 gas contaminated with N2 gas, until CO2 breakthrough takes place. It should be pointed out for the all cases that the rate of CH4 production gradually reduces because of the opening of the production well, which results in the reduction of initial pressure (1.5 MPa) to an attributed boundary condition (0.1 MPa). If it is seen from a realistic view, the injection of pure CO2 is controlled by the CO2 breakthrough at the completion of operation, whereas the case is completely different for pure N2 injection and determined by the quality of produced CH4.

Flow rates of CH4, CO2, and N2 at the production well as a function of time for three various injection schemes: a pure CO2, b 5050/CO2:N2, and c pure N2 (Pini et al. 2011)

However, these notions can be described more based on the CH4 purity in produced gas and the quantity of CH4 recovered as a function of cumulative gas injection quantity for various ECBM operational schemes, which are visualized in Fig. 7a, b, respectively. It is worth to notify that the x-coordinate is more appropriately used for indicating the cumulative gas injection instead of time and a uniform injection pressure (Pinj = 4 MPa) was attributed for these simulation purposes. It can be clearly visualized that the purity of produced CH4 becomes more contaminated due to the addition of N2 in injected gas, which creates also an overlapping between the CH4 desorption and N2 injection fronts discussed above. On the contrary, pure CO2 in injected gas increases the purity of CH4 in produced gas until the ending of the recovery operation. Besides these, compared with the pure CO2, the addition of N2 in injected gas mixtures permits initial methane recovery quite faster according to the quantity of CH4 recovered. But, it becomes possible to attain the total recovery of CH4 earlier when the amount of CO2 starts increasing in the feed and is shown by the large crossover visualization at CH4 recovery values. The characteristic of CH4 displacement can be described more effectively with CO2 content for its higher adsorptivity analogous to both CH4 and N2. Results that display a resembling crossover have been examined by presuming uniform porosity and permeability and by using a method to achieve the solutions of analytical approach of gas transport at the time of ECBM recovery operation. However, the slower primary recovery is observed when the injected gas mixture is enriched with CO2 and can be further imposed to a declination of local flow velocity caused by the reduction of CO2 from the fluid phase.

Influence of coal swelling and permeability

Previous studies have shown that the problems related to the reduction in permeability are happened by injection of CO2. It is anticipated that the reduction in permeability mainly restricted around the injection well, in which the concentration of CO2 is large (Schepers et al. 2011). Figure 8 represents the permeability ratio k/k0 for Case B, during the initial 4 days of injection at the injection well (z = 0) as a function of time. The initial permeability chooses a value of near to 4.4 mD for pure CO2, though it has been lowered down by 0.4 mD after 4 days, which correspondently reduces about one order of value. On the other hand, the opposite situation takes place for pure N2, which approximately doubling the value of initial permeability.

Permeability ratio k/k0 at the injection well as a function of time for Case B (strong swelling) for various ECBM scenarios with various injection compositions (Pini et al. 2011)

The decrease in permeability has significant influences on ECBM process itself (Pashin 2016). Here, Fig. 9a, b represents the quantity of injected CO2 gas in the coal seam for different ECBM scenarios as a function of time according to the weakness (Case A) and strongness (Case B) of coal swelling, respectively. For Case A, the obtained curves are scattering out quietly, as the amount of CO2 gas in injected mixture is increasing continuously. On the contrary, for Case B, these curves are considerably smaller than the Case A for 4 different injection scenarios. Consequently, compared to the mixture of 80:20/CO2:N2, it is evident that the increasing feed concentration of CO2 is not reflected when it is injected continuously for the pure CO2 case. However, these analyzed results show that if the goal is to increase the storage of CO2, then it should be needed to inject a mixture of CO2/N2 effectively than only the injection of pure CO2.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis is a way of showing the uncertainty occurred according to the variation in the output of a mathematical model, which can be influenced by the changes of qualitative and quantitative input values in the input of the model. Figure 10 shows the testing of different parameters like Young’s modulus, cleat porosity, Poisson’s ratio, CO2 desorption time, CH4 desorption time, CO2 Langmuir volume, etc., that are alternated within reasonable range.

Sensitivity analysis on various reservoir parameters (He et al. 2013)

Based on the sensitivity analysis, the result provides an illustration on both the CO2 injection and CH4 production by comparing the effects of major CBM properties. It also founds that the simulation result can be affected little by the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio, where cleat permeability, Langmuir strain, and volume and desorption time have serious effects on the result. For instance, the higher the desorption time of CH4 extends, the slower the desorption process would be. Not only that, but also the rate of enhancing cleat permeability would be slower due to the slow process of matrix shrinkage. Consequently, the gas production rate would be slower within the restricted time range. After that, the producing rate of gas production will be declined considerably from the faster producing rate without any doubt based on the definite time range.

The role of geochemical properties in reservoir and geomechanical aspects of CO2 sequestration

The role of elastic modulus

Since elastic modulus has a proportional relationship with the swelling-induced stress in coal seams, that is why it is considered as a vital factor to predict the permeability in coal seams during the CO2 injection (Sander et al. 2014). Previous studies have analyzed the effect of elastic modulus on the methane production along with the quantity of producible methane in coal seams and predicted that the higher value of permeability results from the lower value of elastic modulus (Figs. 11, 12). This is occurred because the greater shrinkage of matrix causes greater enhancement of the permeability during the CBM production, as the value of elastic modulus is low at that time. In addition, at the time of CO2-injected ECBM recovery operation, the permeability reduction takes place due to the increase in coal swelling, which further leads to the slower production rate of the CH4 gas. Therefore, it can be said that elastic modulus is the second parameter after the initial cleat permeability to predict about the reservoir simulation during both the time of CBM production and ECBM recovery operation.

Influence of elastic modulus of coal on permeability prediction (Sander et al. 2014)

Influence of elastic modulus on the amount of recoverable methane from a coalbed (Viete and Ranjith 2007)

However, it is evident that the mechanical responses from a coal matrix are very essential to assess the cap rock integrity, fracture/fault reactivation, wellbore stability, and ground surface movement during the CO2 injection (Viete and Ranjith 2007). Therefore, to analyze the mechanical responses obtained from the injection of CO2 to the coal seams, a number of hydromechanical models have been employed for few decades. These models are important to highlight the previous aspects so that the influence of the mechanical characteristics related to the hydrocarbon reservoir on the ground surface movements can be studied during the CO2 injection. These mechanical properties provide a qualitative sense about its effect on the results, though they are not applicable directly to coal beds. Figure 13 represents the changes of the ground surface displacement based on the elastic modulus of the reservoir, which shows that the ground surface movement can enhance by the increasing value of the elastic modulus. The potential for the uplift/subsidence in this example mostly depends on the structural geology and production rate of the field. For instance, the rock mass deformation may be resulted from the fracture/subsidence reactivations and subsequent gas leakage to the surface during the ground uplift and movement. However, in addition to the damage to the existing ground movement on rare occasional disasters, the damage to the injection/production facilities can be significant. For instance, the subsidence of the Baldwin Hills Dam is confirmed to be occurred due to the fracture reactivation as a cause of gas injection into the nearby coalfield initiated as production increasing measure.

Sensitivity of the ground surface subsidence to elastic modulus value (Viete and Ranjith 2007)

The role of strength

Since the mechanical strength of coal has an effect on the post-failure permeability of coal, it is a crucial parameter in both reservoir and safety performances during the CO2 sequestration operation. Previous studies conducted on the coal rocks have shown that permeability reduces at the time of initial states of triaxial compression test and then it begins to enhance in the pre-failure deformation stage where it is considered non-elastic (Sukla et al. 2013). When newly created fractures give the maximum permeability value after the post-failure stage, then permeability keeps trying to reach a peak, though it drops down back during the residual stage (Fig. 14a–d). These inspections provide evident for a coal seam that the reservoir performance can be influenced by the coal deformation and failure during the CO2-injected ECBM recovery operation.

Permeability during triaxial compression on a mudstone, b sandy shale, c fine sandstone, and d coal (Masoudian 2016)

The role of Poisson’s ratio

An accurate measurement of Poisson’s ratio is required to assess the value of reservoir effective stress resulted from the reservoir expansion/compaction and help performing in permeability prediction. Figure 15 shows the results of the previous studies performed especially on sensitivity analysis where the changes in permeability prediction have been affected by the changes in value of Poisson’s ratio. This case is more evident and significant when the value of Poisson’s ratio is quite high. The influence of changes in Poisson’s ratio in CH4 production and recovery operation has been investigated by analyzing the reservoir properties. In Fig. 16, it can be shown that the influence of higher Poisson’s ratio on the ECBM recovery operation is very significant with greater methane recovery, but not so effective on CH4 production during the CBM operation. Because the influence of adsorption-induced swelling moderately eliminates the influence of desorption-induced shrinkage on permeability during ECBM operation, which further assists the reservoir expansion/compaction to become the principal maintained factor in permeability assessment. On the contrary, the influence of compaction and shrinkage on the permeability assessment remains as the same order during CBM operation.

Influence of Poisson’s ratio on the predicted permeability during CH4 production from coal seam (Pan and Connell 2012)

Influence of Poisson’s ratio on the quantity of recoverable methane from coal seam (Masoudian et al. 2013)

Conclusions

Gas sorption primarily accounts for the maximum amount of CO2 retained in coal seam and makes a better way of storage than gas compression. The equilibrium density in the corresponding gas phase is lower compared to the density of gas in adsorbed phase. Moreover, it is conferred that coal seams may store 2–3 times the quantity of gas retained in a conventional gas reservoir at similar depth and pressure. The naturally stored CH4 gas in the coal seam is recovered through the adsorption/desorption process under in situ reservoir conditions. In this study, a number of various injection schemes have been inspected to analyze the efficiency of mixing pure CO2 and pure N2 in flue mixture for injecting into a coal seam initially saturated with CH4, which further creates a better way to inject flue gas directly by eliminating less interesting and much expensive CO2 capture stage. In section “Influence of injected gas composition,” attractive results have been achieved in the recovery of the pure gas in place based on the purity and production rate, which may be found by observing the unique adsorption characteristic of each element on the coal matrix. When the initial recovery is slower and the adsorption of CO2 is higher from the CH4 adsorption, then the total recovery is allowed faster than the preliminary recovery. In this case, the displacement is more effective. On the other hand, in spite of having earlier breakthrough and a behavior of contaminating the produced methane gas, the mixing of N2 allows faster preliminary recovery for its less adsorbing power. From this realistic view, it can be signified as a better trade-off in the case of incremental methane recovery for using as a quality produced fuel.

The volume alternation of the coal particle related to gas sorption can alter factually the scenario just explained. According to section “Influence of coal swelling and permeability,” it is found that the coal swelling caused to reduce robust permeability when exposed to CO2 substantially, has a strong impact on the performance of an ECBM recovery operation. Particularly, for Case B, the simulation results exhibit that the implication of a mixture with composition 80:20/CO2:N2 permits both injecting and storing a uniform amount of pure CO2. The coal swelling and resulting shut down of the fractures will preliminary influence the place near to the injection well, where the amount of CO2 is quiet rich, therefore inhibiting the exploitation of the total coal seam volume. Based on the inspections from past simulation researches (Durucan and shi 2009), the results achieved in this study express new paths toward the few striking options desired to tackle the injectivity problems just interpreted and that need to be further studied. This work also involves the application of flue mixtures as a way of holding the permeability high adequately, as well as the improvement of design conditions upon the behavior of injection and production wells, as a route of optimizing CO2 storage and CH4 recovery.

Abbreviations

- \(\varphi_{\text{t}}\) :

-

Overall porosity

- \(\varphi_{\text{c}}\) :

-

Cleat porosity

- \(\varphi_{\text{p}}\) :

-

Macroporosity

- n c :

-

Number of components

- n :

-

Adsorbed phase concentration (mol/m3)

- c :

-

Actual gas phase concentration (mol/m3)

- c 1 :

-

Effective pressure coefficient (1/Pa)

- c 2 :

-

Swelling coefficient

- u :

-

Superficial velocity of fluid (m/s)

- t :

-

Time (s)

- z :

-

Space coordinate (m)

- L :

-

Coal seam length (m)

- k mi :

-

Mass transfer coefficient of component (1/s)

- n * :

-

Equilibrium adsorbed phase concentration (mol/m3)

- n ∞ :

-

Saturation capacity per unit mass adsorbent (mol/m3)

- \(\rho_{\text{s}}\) :

-

Coal bulk density (kg/m3)

- y :

-

Molar fraction of gas (m3/mol)

- \(P\) :

-

Equilibrium gas phase pressure (Pa)

- b s :

-

Equilibrium constant of Langmuir model for swelling (1/Pa)

- \(\mu\) :

-

Dynamic viscosity (Pa s)

- \(v\) :

-

Interstitial fluid velocity (m/s)

- \(k\) :

-

Permeability (m2), 1 mD = 9.869233 × 10−6 m2

- \(p_{\text{c}}\) :

-

Confining pressure (Pa)

- S :

-

Total swelling

- s ∞ :

-

Saturation capacity in swelling

- b :

-

Langmuir equilibrium constant (1/Pa)

- α :

-

Sorption isotherm coefficient

- β :

-

Swelling isotherm coefficient

References

Arri LE, Yee D, Morgan WD, Jeansonne MW (1992) Modeling coalbed methane production with binary gas sorption, presented at the SPOE Rocky Mountain Regional Meeting, Casper, WY, USA, May 1992. SPE 24363

Bae JS, Bhatia SK (2006) High-pressure adsorption of methane and carbon dioxide on coal. Energy Fuels 20(6):2599–2607

Busch A, Genssterblum Y, Krooss BM (2003) Methane and CO2 sorption and desorption measurements on dry Argonne premium coals: pure components and mixtures. Int J Coal Geol 55(2):205–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-5162(03)00113-7

Bush A, Gensterblum U (2011) CBM and CO -ECBM related sorption processes in coal. A review. Int J Coal Geol 87(2):49–71

Bustin RM, Cui XJ, Chikatamarla L (2008) Impacts of volumetric strain on CO2 sequestration in coals and enhanced CH4 recovery. Am Assoc Pet Geol Bull 92(1):15–29

Chen Z, Liu J, Elsworth D, Connell LD, Pan Z (2010) Impact of CO2 injection and differential deformation on CO2 injectivity under in situ stress conditions. Int J Coal Geol 81(2):97–108

Connell LD, Sander R, Pan Z, Camilleri M, Heryanto D (2011) History matching of enhanced coal bed methane laboratory core flood tests. Int J Coal Geol 87(2):128–138

Connell LD, Pan Z, Camilleri M, Meng SS, Down D, Carras J, Zhang W, Fu X, Guo B, Briggs C, Lupton N (2014) Description of a CO2 enhanced coalbed methane field trial using a multi-lateral horizontal well. Int J Greenh Control 26:204–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2014.04.022

Cui X, Bustin RM, Chikatamarla L (2007) Adsorption—induced coal swelling and stress, implications for methane production and acid gas sequestration into coal seams. J Geophys Res-Solid Earth 112:102. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004jb003482

Durucan S, Shi JQ (2009) Improving the CO2 well injectivity and enhanced coalbed methane production performance in coal seams. Int J Coal Geol 77(1):214–221

Fitzgerald JE, Pan Z, Sudibandriyo M, Robinson RL Jr, Gasem KAM (2005) Adsorption of methane, nitrogen, carbon dioxide and their mixtures on wet Tiffany coal. Fuel 84:2351–2363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2005.05.002

Fujioka M, Yamaguchi S, Nako M (2010) CO2-ECBM field tests in the Ishikari Coal Basin of Japan. Int J Coal Geol 82(3):287–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2010.01.004

Gale JJ (2004) Using coal seams for CO2 sequestration. Geologica Belgica 7(3):99–103

Gale J, Freund P (2001) Coal-bed methane enhancement with CO2 sequestration worldwide potential. Environ Geosciences 8:210–217

Gilman A, Beckie R (2000) Flow of coalbed methane to a gallery. Tansp Porous Media 41(1):1–16

Godec M, Koperna G, Gale J (2014) CO2-ECBM: A review of its status and global potential. Energy Procedia 63:5858–5869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2014.11.619

Gray I (1987) Reservoir engineering in coal seams. Part 1. The physical process of gas storage and movement in coal seams. SPE Reserv Eng SPE Pap 12514:28–34

He Q, Mohaghegh SD, Gholami V (2013) A field study on simulation of CO2 injection and ECBM production and prediction of CO2 storage capacity in unmineable coal seam. J Pet Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/803706

Li X, Fang Z (2014) Current status and technical challenges of CO2 storage in coal seams and enhanced coalbed methane recovery: an overview. Int J Coal Sci Technol 1(1):93–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-014-0002-9

Masoudian MS (2016) Multiphysics of carbon dioxide sequestration in coalbeds: a review with a focus on geomechanical characteristics of coal. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng 8:93–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2015.080.002

Masoudian MS, Airey DW, EL-Zein A (2013) An experimental investigation on mechanical behavior of CO2 saturated coal specimens. Aust Geomech J 48(4):197–202

Mavor MJ, Gunter WD, Robinson JR (2004) Alberta multiwell micro-pilot testing for CBM properties, enhanced methane recovery and CO2 storage potential. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, Houston, September. SPE-90256

Mazumder S, Karnik AA, Wolf K-HAA (2006) Swelling of coal in response to CO2 sequestration for ECBM and its effect on fracture permeability. SPE J 11(3):390–398. https://doi.org/10.2118/97754-pa

Mazzotti M, Pini R, Storti G (2009) Enhanced coalbed methane recovery. J Supercrit Fluids 47:619–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2008.08.013

Michaeel G, Anderss DE, Law BE (1993) Geochemical evaluation of upper Cretaceous Fruitland formation coals, San Juan Basin, New Mexico and Colorado. Org Geochem 20:475–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6380(93)90094-R

Oudinot AY, Koperna GJ Jr, Philip ZG, Liu N, Heath JE, Wells A, Young GB, Wilson T (2011) CO2 injection performance in the Fruitland Coal Fairway, an Juan Basin: results of a filed pilot. SPE J 16:864–879. https://doi.org/10.2118/127073-pa

Pan Z, Connell LD (2007) A theoretical model for gas adsorption-induced coal swelling. Int J Coal Geol 69(4):243–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2006.04.006

Pan Z, Connell LD (2012) Modeling permeability for coal reservoirs: a review of analytical models and testing data. Int J Coal Geol 92:1–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2011.12.009

Pan Z, Ye J, Zhou F, Tan Y, Connell L, Fan J (2017) CO2 storage in coal to enhance coalbed methane recovery: a review of filed experiments in China. Int Geol Rev. https://doi.org/10.1080/00206814.2017.1373607

Pashin JC (2016) Geologic considerations for CO2 storage in coal. In: Singh TN (ed) Geologic carbon sequestration: understanding reservoir behavior. Springer, Berlin, pp 137–159

Perera MSA, Ranjith PG (2015) Enhanced coal bed methane recovery: using injection of nitrogen and carbon dioxide mixture. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118991978.hhces218

Pini R, Ottinger S, Burlini L, Storti G, Mazzotti M (2009) Role of adsorption and swelling on the dynamics of gas injection in coal. J Geophys Res 114(B4):B04203. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008jb005961

Pini R, Storti G, Mazzotti M (2011) A model for enhanced coal bed methane recovery aimed at carbon dioxide storage. Adsorption 17:889–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10450-011-9357-z

Reid RC, Praunitz JM, Poling BE (1987) The properties of gases and liquids, 4th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Rice CA, Nuccio V (2000) Water produced with coal-bed methane. US Geol Survey Fact Sheet, FS-156-00, Washington, DC

Sams WN, Bromhal G, Jikich S, Ertekin T, Smith DH (2005) Field-project designs for carbon dioxide sequestration and enhanced coalbed methane production. Energy Fuels 19(6):2287–2297

Sander R, Connell LD, Pan Z, Camilleri M, Heryanto D, Lupton N (2014) Core flooding experiments of CO2 enhanced coalbed methane recovery. Int J Coal Geol 17:113–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2014.06.007

Schepers K, Oudinot A, Ripepi N (2011) Enhanced gas recovery and CO2 storage in coal bed methane reservoirs: optimized injected gas composition for mature basins of various coal rank. AAPG Eastern Section Meeting, Washington, DC

Scott AR (2002) Hydrologic factors affecting gas content distribution in coal beds. Int J Coal Geol 50:363–387

Shao SWS, Ranjith PG, Viete DR, Jaysinge D (2012) Carbon dioxide storage in coal: reconstituted coal as a structurally homogeneous substitute for coal. Int J Coal Prep Util 32:265–275

Sukla R, Ranjith PG, Choi SK (2013) Mechanical behavior of reservoir rock under brine saturation. Rock Mech Eng 46:83–93

Talapatra A (2019) Optimization of the evaluation indexes of coalbed methane gas extraction. Int J Eng Sci Technol 11(3):11–18. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijest.v11i3.2

Talapatra A, Chowdhury AI, Ujjaman S (2019) A smart review on the gas transportation model of coalbed methane gas based on the optimized pipeline network 43(2):169–176. https://doi.org/10.30464/jmee.2019.3.2.169

Thomas FD, Beatie AM (2001) Debunking the natural gas “clean energy” myth: coalbed methane in Wyoming's powder river basin. Environ Law Rep 31:566–575

Viete DR, Ranjith PG (2006) The effect of CO2 on the geomechanical and permeability behavior of brown coal: implications for coal seam CO2 sequestration. Int J Coal Geol 66:204–216

Viete DR, Ranjith PG (2007) The mechanical behavior of coal with respect to CO2 sequestration in deep coal seams. Fuel 86:2667–2671

Vishal V, Ranjith PG, Singh TN (2013) CO2 permeability of Indian bituminous coals: implications for carbon sequestration. Int J Coal Geol 105:36–47

White CM, Smith DH, Joness KL, Goodman AL, Jikich SA (2005) Sequestration of carbon dioxide in coal with enhanced coalbed methane recovery-a review. Energy Fuels 19(3):659–724. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef040047w

Yamaguchi S, Ohga K, Fujioka M, Nako M (2006) Field test and history matching of the CO2 sequestration project in coal seams in Japan. Int Journal of the Society of Materials Engineering for Resources 13(2):64–69. https://doi.org/10.5188/ijsmer.13.64

Acknowledgements

Great thank is presented to my undergraduate supervisor for supporting me to conduct this research. The author is also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, criticism, and suggestions on my work helped me much in improving the original manuscript significantly. It is my cordial prayer to the God to bring her in my life quickly so that she can motivate me to do more research by staying beside me in future on the fields of sustainable energy production, and finally holding a belief in God, I just want to say, “Jai Shri Ram.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Talapatra, A. A study on the carbon dioxide injection into coal seam aiming at enhancing coal bed methane (ECBM) recovery. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 10, 1965–1981 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-020-00847-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-020-00847-y