Abstract

Matrix-acidizing operations have been accounted to be the most hazardous and environmentally harmful among all the well-stimulation techniques. For instance, diesel oil-based emulsified acids have been prohibited from usage due to their high level of toxicity. There is, therefore, a dire need for emulsified acids that are environmentally viable and technically competent to replace the diesel-based emulsified acids. In this study, a novel oil-based environmental friendly emulsified acid has been synthesized from Jatropha curcas oil and, then, compared against diesel and palm oil-based emulsified acids. The technical evaluation of the three acids has been done based on experimental results obtained from thermal stability, droplet size analysis, rheological study, acid solubility, and toxicity screening. In addition, core flooding experiments have been conducted to evaluate the performance of the three emulsified acids as well stimulants. The results revealed that Jatropha oil-based emulsified acid has the potential to replace diesel-based emulsified acid. Jatropha oil-based emulsified acid was found to perform better than the diesel-based emulsified acid as indicated by having greater thermal stability and more popular rheological properties at varying temperatures of ambient, 50 and 70 °C. Furthermore, it possessed a lower toxicity load and a higher retardation effect on acid solubility than that of the diesel oil-based emulsified acid. The core flooding results have also indicated better well-stimulation performance of Jatropha-based emulsified acid as compared with diesel-based emulsified acids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Matrix acidizing is a technique that extensively used to increase the production of oil and gas from a reservoir, especially in the case when the reservoir is suffering from formation damage or has a naturally low permeability. Approximately 60 and 40% of world’s oil and gas, respectively, reside in carbonate reservoirs (Schlumberger 2007), where it is hard to achieve a successful acid stimulation due to high reactivity of the acid with the formation. As a result, the possibility of making deep flow conduits, known as wormholes, will be reduced. The wormholes allow the hydrocarbons to flow into the wellbore for production. One of the techniques used to overcome this problem is using retarding acid systems of various types that are capable of minimizing dissolution reaction (Navarrete et al. 2000).

In general, there are four types of retarding acidizing fluids, gelled-based acids, chemically retarded acids, and emulsified acids. The prior three have limitations which prevent their usage in matrix-acidizing operations such high injection pressure is required for pumping gelled-based acids, large amount of oil is employed for chemically retarded acids (Portier et al. 2007). Chelating agent-based stimulant has a low dissolving power than HCl thus need to be injected in huge amounts making them financially unviable (Markey et al. 2014). Emulsified acids have a composition which provides viscosity and mobility suitable for matrix acidizing.

Emulsion type generally favored for acidizing is the coarse emulsion courtesy of having high acid volume and low surfactant requirement, contrary to microemulsions which require high surfactant concentration and possess little quantity of acid (Buijse and Domelen 1998; Navarrete et al. 1998). Furthermore, as per literature review, it has been observed that water-in-oil-type emulsion provides better retardation ability than an oil in water emulsion (Nierode and Kruk 1973; Sarma et al. 2007).

Along the history of application, the emulsified acids have shown satisfactory effectiveness and valuable attractive features. Their high viscosity, due to the presence of oil, is ideal to prevent fluid losses as well as providing a retarding effect on the dissolution reaction (Williams and Gidley 1979a). Yet, the emulsion is mobile enough to flow easily in the reservoir. In addition, the emulsified acids also provide corrosion inhibition for the well equipment and cater flow to low permeable zones.

Although matrix acidizing has been an efficient way to increase production, the number of environmental concerns have risen in the recent years.

A research report from UCLA highlighted the risks presented by well-stimulation operations other than hydraulic fracturing, the report consisted of field activity data from April 2013 to August 2015 obtained from various monitoring agencies such as California Department of Conservation’s Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR) (Abdullah et al. 2016). It was stated that in comparison with hydraulic fracturing which uses 99.5% of water along with only 0.5% chemical content, acidizing operations have chemical concentrations in the range of 6–18%, and these chemicals have been labelled as of high concern by the Environmental Policy Agency (EPA) with matrix acidizing generally having the heaviest amount generally.

Energy Policy Act of 2005 (Safe Drinking Water Act, Section 322) (Congress 2005) has proscribed diesel fuel usage in well-stimulation operations due to the high level of carcinogenic content in diesel, which causes elevation in lung cancer rates, skin damage, vision impairment, clotting deficiency and many other health-related risk factors, and environmental concerns. All diesel-based products including xylene, benzene, and toluene are, therefore, prohibited from usage. In February 2014 EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) (Bishop and Bohlen 2014) published Underground Injection Control program to provide regulators with guidelines when giving permits to operators, to prevent diesel fuel usage to ensure environmental security in exploration and production operations.

This is a major concern as acidizing fluid consisting of diesel can contaminate the groundwater when it is flushed into the surface; moreover, after reacting with the subsurface minerals, the acidizing medium becomes more dangerous; thus, during production, the fluid flowback (returning fluid) is hazardous even after treatment when releasing it into the local water supply.

Due to these environmental concerns, there is a dire need to replace diesel oil-based emulsified acid with a green fluid which is technically viable and low toxic in nature.

Plant oil is believed to have properties such as stability, viscosity, reaction, and corrosion retardation that suits the technical need of acidizing operations along with being of low toxicity than diesel oil (Adesina et al. 2012). Triglyceride oils such as from palm, coconut, sunflower, and Jatropha curcas have been utilized in various oil and gas exploration and production phases, such as in drilling (Adesina et al. 2012; Fadairo et al. 2013) and enhanced oil recovery operations as surfactants (Majidaie et al. 2012; Mumtaz et al. 2015; Soffian et al. 2015; Karasinghe et al. 2016; Nordiyana et al. 2016) oil phases for drilling and completion fluids (Amanullah 2005; Okeke et al. 2013; Yegin et al. 2017) and corrosion inhibitors (Anand and Meenakshi 2011; Malarvizhi et al. 2015; Rostron et al. 2017) due to being non-toxic, biodegradable and possessing high viscosity, thermal stability, corrosion inhibition and effective interfacial tension alteration capabilities; these properties enable greater cutting carrying capability in drilling fluids (Fadairo et al. 2013), better miscibility of fluids in flooding operations (Jeirani et al. 2006) and prevention against deterioration of subsurface metal equipment (Mohadyaldinn et al. 2017).

As observed from literature review of previous studies Jatropha curcas oil being a long-chain triglyceride is able to provide a better performance. Jatropha curcas oil is believed to have properties that suits the technical need of acidizing operations along with being of low toxicity than diesel oil such as viscosity, stability, and acid reactivity retardation.

Jatropha oil is an inedible oil which means it does not affect the food crops, the oil produced from its seed ranges from 30 to 50% (by weight), whereas the oil produced from kernel is up to 60% (Pramanik 2003; Mofijur et al. 2012). Jatropha has more ratio of unsaturated fatty acids, courtesy of being rich in oleic and linoleic fatty acids which have a carbon chain length of 18, a result of which it has a higher viscosity.

Palm oil has the one of the highest yield of oil production in vegetable oils. It is an edible oil majorly used in the food industry (90%); however, 10% is productively utilized for chemical processing (Koushki et al. 2015), consisting of a high ratio of saturated fatty acids mainly palmitic fatty acid which is useful in many applications such as surfactant synthesis. It is medium chain triglyceride oil thus has a carbon chain up to 12 (Chempro Company 2017).

For this purpose, a water-in-oil emulsion system was adapted. The emulsified acid made of Jatropha oil was tested and compared with palm oil emulsion for thermal stability, droplet size analysis, rheological study, acid solubility and toxicity load, against diesel oil-based emulsified acid.

After the evaluation and screening of the triglyceride-based emulsions against diesel oil-based emulsion for prior mentioned parameters, further study was acidizing rock core in a field simulated environment, to evaluate the practicality of Jatropha oil-based acid emulsion and compare it with diesel-based emulsified acid (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Materials

Diesel and palm oil were purchased from a local supplier and Jatropha oil was ordered from BATC Development BHD. 15 weight% hydrochloric acid, nonionic surfactants: Span80 and Tween80 were obtained from Benua Sains SDN BHD. A Linear alcohol-based nonionic surfactant with an ethoxylation grade of 9 was obtained from a proprietary company.

Methodology

Preparation of emulsified acid

The emulsified acid synthesized was a water-in-oil type with 70:30 ratio of acid to oil (Sidaoui et al. 2016), this allows high mobility, increases retardation effect and minimizes the quantity of oil as observed in various research studies (Al-Anazi et al. 1998; Navarrete et al. 1998; Bazin and Abdulahad 1999; Robert and Crowe 2000; Chan et al. 2006; Siddiqui et al. 2006; Sidaoui et al. 2016).

A blend of two surfactants one being highly hydrophilic with an HLB value of 15, while the other being lipophilic with an HLB value of 4.3 were utilized to obtain an emulsifier (Sarma et al. 2007), this is believed to provide a stronger bond between the aqueous phase and oil phase.

The formulated emulsifier was mixed with the oil phase for a period of 10 min. Hydrochloric acid of 15 wt% concentration was introduced into the micelle phase of oil and emulsifier by spraying, to achieve an atomized dispersion of acid droplets in the oil phase (Al-Mutairi et al. 2009a). As the addition of acid is performed the mixture is stirred with an increase in speed from 600 to 1500 RPM for 20 min to achieve a stable water-in-oil emulsion using the IKA Eurostar 20 Digital stirrer.

For determining how much amount of the two surfactants (surfactant A and surfactant B) must be added to obtain a specific HLB value-based emulsifier, the following equations have been used (Croda Europe Ltd 2009):

where X = HLB value to be attained, A = Surfactant A and B = Surfactant B.

Electrical conductivity

To ensure that the formed type of emulsion is water in oil, electrical conductivity tests were conducted. All the three emulsion types were tested for near zero electrical conductivity (Nasr-El-Din et al. 1999, 2001; Xiong et al. 2010; Zakaria and Nasr-El-Din 2015; Cairns et al. 2016). If a slight electrical conduction was observed, then the emulsion was mixed for another 30 min, after which the emulsion prepared showed no electrical conduction (Sayed et al. 2012). Figure 2 shows the circuit diagram used for electrical conductivity testing of the fluid, in which the probes connected to the multimeter and power source were dipped into the emulsified acid sample to check for conductivity.

Ambient temperature testing

Initially, two type of emulsion systems were formed to investigate the stability at ambient temperature. Emulsion 1 consisted of surfactants, Span80 (HLB 4.3) and Tween80 (HLB 15), whereas emulsion 2 was made from a combination of Span80 (HLB 4.3) and the proprietary surfactant (HLB 13.3). Both emulsions had a 5.1 HLB value as used by Sarma et al. (2007). The oil used for the test was of Jatropha curcas and 15 wt% hydrochloric acid was used as the water phase. Both emulsions were visually inspected for phase separation under ambient temperature, to see which emulsion remains stable the longest.

Thermal stability

The thermal stability of the selected emulsion has been tested by placing it in CTE M1001 29 L Water bath. Repeated tests have been conducted at temperatures of 50 and 70 °C, and at different values of surfactant concentration and HLB. The effect of temperature and time on the composition was observed.

Droplet size

The droplet size measurement for each type of emulsified acid has been conducted using the HORIBA LA-960, Laser Scattering Particle Size Distribution Analyzer (Fig. 3). This device can measure sizes in the range of 10 nm–5000 µm, with full compliance of ISO 13320 standard.

Rheology

The relationship between viscosity and shear stress, at temperatures of 25, 50 and 70 °C for the three emulsified acid types was observed using Anton Paar’s Modular Compact Rheometer, MCR302 (Fig. 4). Following the Ph. Eur. 2.2.10—Rotating viscometer method (The European Pharmacopoeia 2008).

Acid solubility

To determine the amount of rock (carbonate) solubilized by each emulsified acid, the API RP-40 acid solubility tests were conducted at ambient temperature and 70 °C (American Petroleum Institute 1998). Approximately 1 g powder of an Indiana Limestone core sample was used for each test. The powder was made finer than a US sieve 80 mesh. The sample powder was placed in 150 cc sample of emulsified acid for a period of 60 min without stirring at ambient condition for 25 and for 70 °C it was placed in the oven. It was then filtered and rinsed using deionized water on a pre-weighed filter paper. Since the emulsions were too viscous to pass through the filter paper, a vacuum pump was used to create suction pressure in the conical flask collecting the filtrate. After filtration, the sample collected on the filter paper was dried and weighed. The steps of the process are presented in Fig. 5. To calculate the acid solubility percentage, the following formula was used:

where A.S. = acid solubility, W1 = initial sample weight and W2 = final sample weight.

Toxicity

The toxic effect of the emulsions has been investigated by using the Lethal Concentration Test (LC50) on Danio rerio (commonly known as zebrafish). The LC50 test is recommended by Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (Update et al. 2014) and USEPA (Weber et al. 1991) for acute toxicity test of fish. The test was conducted for 48 h in concentrations of 0 (control), 10, 40, 70 and 100 ppm for the three emulsified acids, to determine and compare the concentrations acceptable for environmental exposure. The LC50 was determined using the Arithmetic method of Karber (Adedeji et al. 2008; Kärber 1931; Dede and; Kaglo et al. 2001) which is shown in Eq. (4):

Core acidizing

Core preparation

Indiana Limestone cores of approximately 76.2 mm (3 in.) length and 38.08 mm (1.5 in.) diameter were selected, these cores were cleaned of all fluid using the Dean Stark Apparatus and were dried in the Oven at 70 °C for 12 h. The porosity and permeability were measured using the gas permeameter, shown in Fig. 6, after which the cores were saturated with 10,000 ppm brine for 6 h using the desiccator.

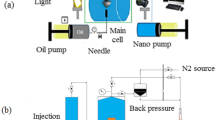

Core flooding

The saturated samples were then put in the core flooding equipment (FES 350) at a temperature of 70 °C, as shown in Fig. 7. A back pressure of 700 psi, confining pressure of 1300 psi, the injection rate was set at 0.5 cc/min. The core was injected first with brine to determine permeability of the core by recording the differential pressure points using Darcy’s Law, as the fluid moves across the core. The 15 wt% HCl was then injected until pressure drop was observed indicating the breakthrough. The cores were then flushed with brine to remove stimulation fluid and was cleaned, dried and was measured for weight, porosity and permeability.

Results and discussion

Ambient temperature testing

The two emulsion systems namely, emulsion 1 and emulsion 2 were tested for stability at ambient temperature condition. Emulsion 1 separated in 4 h, while emulsion 2 started to separate after 9 h. Therefore, emulsion 2 was selected for further thermal stability testing because of long-term stability at ambient temperature. The following calculation was done to adjust the emulsifier HLB value to 5.1 (using Eqs. 1, 2):

For emulsion 1 (Span 80 + Tween 80)

For emulsion 2 (Span 80 + Proprietary Surfactant)

Thermal stability via change in surfactant concentration

Following the ambient temperature stability test, thermal stability tests for Jatropha, diesel and palm oil-based emulsified acids were repeatedly conducted at various surfactant concentrations (1, 1.3, 1.5, 1.7 and 2 ml) at 50 and 70 °C, with a fixed 5.1 HLB value of the emulsions. Figure 4 2 shows the effect of surfactant concentration on each of the emulsified acids. At initial concentration the emulsion based on Jatropha oil and diesel oil remain stable at 50 °C for a few moments but started separating in 1 h. In the case of palm oil-based emulsion, separation started within half of the time of the separation of Jatropha and diesel-based emulsion. With increase in surfactant concentration up to 2 ml, Jatropha oil-based emulsified acid exceeded the stability period of both diesel oil and palm oil-based emulsions. The stability period of Jatropha increased up to 5 h for 50 °C and up to 3 h for 70 °C, whereas the stability period of palm oil-based emulsion and diesel oil-based emulsion at 50 °C are 270 min and 3 h, respectively. At 70 °C a relatively close stability range was observed for palm oil and diesel oil-based emulsions, which is 132 min for the palm-based emulsion and 126 min for diesel-based emulsion. Figures 4 3–5 present the state of the three type of emulsified acids, before and after the test (Fig. 8).

Thermal stability via change in HLB

After observing the effect of surfactant concentration, thermal stability test of the emulsions at temperatures of 50 and 70 °C was conducted for surfactant blends with HLB values of 5.1, 5.3, 5.5, 5.7 and 6. The HLB value was kept at 6 to prevent the emulsified acid from phasing towards oil in water phase range. The volume of emulsion concentration was kept at 1 ml for all the samples. Figure 4 6 shows the stability for each of the emulsified acid types at 50 and 70 °C, whereas Figs. 4 7–9 present the state of the emulsions before and after the stability test. The stability for HLB values of 5.1 for Jatropha and diesel was an hour at 50 °C and 30 min for palm oil-based emulsified acid. At 5.3 HLB value palm oil-based emulsified acid gained an improvement of additional 40 min, Diesel-based emulsion remained close to an hour, while Jatropha-based emulsion had a rise of additional 20 min. A rise in stability was observed at 5.5 HLB value with a similar pattern in the three emulsions, at 5.7 HLB value; however, diesel and palm oil-based emulsions had a similar thermal stability time of 87 min, Jatropha had a significant rise of up to almost 2 h. At 6 HLB emulsion made from Jatropha reached 150 min, followed by diesel-based emulsion at 126 min and palm oil remaining stable up to 2 h. A similar pattern was observed at 70 °C Jatropha remained stable up to 15, 30, 34.8, 60 and 78 min at 5.1, 5.3, 5.5, 5.7 and 6 HLB values respectively. Diesel and palm oil-based emulsions retained their thermal stability with 60, 66, 72, 87 and 126 min by diesel emulsion and 9.6, 15, 30, 60 and 69 min for palm-based emulsion. In summary by increasing the HLB value the stability level increased to a certain extent. This might have been because of increase in content of the proprietary hydrophilic surfactant (Fig. 9).

Thermal stability test of emulsions with 6 HLB value

Based on the results of the investigation of changing HLB value discussed above, it was decided to test thermal stability of various emulsifier concentrations with a fixed HLB value of 6, since it was the value at which the 1 ml surfactant concentration remained intact the longest. As indicated in Fig. 4 10, at concentration of 1.3 and 1.5 ml, all the emulsions remained stable for 2–4 h at 50 and 70 °C (apart from Jatropha retaining up to 270 min at 50 °C). Jatropha oil-based emulsion having 1.7 ml surfactant concentration have remained stable for more than 6 h at 50 °C and up to 6 h at 70 °C, whereas the emulsions made from palm oil remained intact for 6 h at 50 °C and 315 min at 70 °C. At 50 °C diesel oil emulsion provided the stability of up to 348 min; however, at 70 °C, it remained intact for 5 h only. Therefore, for Jatropha oil-based emulsion 1.7 ml surfactant concentration with a 6 HLB value was selected for the forthcoming tests. For diesel oil and palm oil-based emulsified acids the composition was further investigated to achieve stability of 6 h at temperatures of 50 and 70 °C. Figures 4 11–13 show the phase change in the three emulsions before and after the stability test (Fig. 10).

Thermal stability test of diesel oil and palm oil

Based on the previous observation, in this step the surfactant concentration was slightly increased to 1.8 ml in emulsions of diesel oil and palm oil, to see if the emulsion remained intact for 6 h. At surfactant concentration of 1.8 ml, diesel oil-based emulsion remained stable for more than 6 h at both temperatures of 50 and 70 °C. For palm oil-based emulsified acid at 50 °C the stability was similar to that of diesel oil-based emulsion, while at 70 °C the emulsified acid remained intact for nearly 6 h with a slight layer of separation beginning to show.

Droplet size measurement

Droplet size distribution affects many characteristics of the emulsion such as its rheology, stability and the emulsion liquid performance (Opedal et al. 2009). The shape and size distribution of the droplets present in the emulsion influence the flow properties. Larger particles flow more easily than smaller particles; however, smaller particles give higher suspension, viscosity and emulsion stability courtesy of having high surface charge (Horiba Instruments 2016), In general, the smaller the droplet size of the emulsions, the more will be its tendency to act as one phase when passing through the rock pores. This will mainly affect the relative permeability of the rock (Hoefner and Fogler 1987). The refractive index is necessary for laser diffraction as it is based upon Mie Theory. Therefore, refractive index of each emulsion was obtained using Refractometer RM40 from Mettler Toledo. Since laser diffraction technique gives results on volumes basis, it is recommended to use median size value for droplet size distribution. Table 1 presents the average droplet sizes attained in prior studies which were considered for verifying suitability of the synthesized emulsified acids. Table 2 shows that all of the three emulsions have median size distribution greater than one micron (Al-Mutairi et al. 2009a), which fall within the range of macroemulsions. Figure 11 indicates that the droplet size distribution of emulsions having Jatropha curcas oil and palm oil is almost same and slightly less than that of the diesel oil-based emulsion. This indicates that triglyceride-based emulsified acids are more stable than diesel-based emulsified acid.

Rheology

The property of shear thinning is highly favorable during the flow of the fluid in the wellbore. Due to the high shear rate, while its flow through the well, the fluid can move easily in the wellbore. After reaching the formation, the viscosity will increase as the shear rate is low in this area (Markey et al. 2014). This characteristic provides better acid placement, acid reaction retardation and a low diffusion rate. This will allow in generation of deep, small diameter-based wormholes, with the possibility of branching an interconnection of pore spaces (Williams and Gidley 1979b). All three of the emulsified acids showed the shear thinning quality at 25, 50 and 70 °C. Jatropha-based emulsion had the highest viscosity followed by that of palm oil-based emulsified acid and then diesel-based. It was considered that because of large molecular mass and having longer carbon chains, the Jatropha oil-based emulsion has higher viscosity than diesel-based emulsion. Thus Jatropha oil-based emulsified acid can perform same as diesel under high shear rate conditions of the wellbore for providing the retarding effect needed for deep wormhole generation. Figure 12 represents the variation of viscosity with shear rate of the three emulsified acids at 25, 50 and 70 °C.

Acid solubility at ambient temperature

The acid solubility test was conducted at ambient temperature to compare the retardation ability of the three emulsified acid solutions. Table 3 presents the acid solubility values at ambient temperature, the emulsion made from Jatropha oil shows the highest retardation effect with acid solubility of 57.2%. The amount of material solubilized by emulsion made from diesel oil (66.95%) is relatively same as the palm oil emulsion (66.78%). These results indicate that Jatropha oil-based emulsion has a higher potential for minimizing the acid reaction rate and Jatropha oil can replace diesel oil as the oil phase in the emulsified acid systems at ambient temperature. The higher fatty acid content of Jatropha provides a higher viscosity and thus a better retardation effect than diesel and palm oil-based emulsions.

Acid solubility at 70 °C

The percentage of acid solubility of the three emulsified acids increased with the increase in temperature; however, the retardation behavior remained the same as at ambient temperature. As evident from Table 4, Jatropha-based emulsified acid retarded the solubility reaction much better than the emulsions made from diesel and palm oil, which had a relatively similar reaction rate. Specifying that even at 70 °C, Jatropha-based emulsion retains its retarding ability courtesy of having a high triglyceride content, the higher viscosity results in slowing down the acid interaction with the surface of the rock. These results aid towards promoting Jatropha as a reliable replacement for diesel in emulsified acids. As per visual inspection (during filtering, drying and weighing) of leftover sample on the filter papers, it was clearly visible that Jatropha oil-based emulsified acid, held the most weight out of the three emulsified acids, as shown in Fig. 13.

Toxicity

The LC50 acute toxicity test is crucial for the fluids used in exploration and production operations. This is mainly to ensure that the fluid is safe for disposal into local water supply as 98% of exploration and production waste comes from produced water (Olajire 2014). Therefore, Danio rerio (zebrafish) were inspected for 50% mortality rate, as per instructions of OECD203 standard.

Tables 5, 6 and 7 show the LC50 values for each of the emulsified acids, determined by the arithmetic method of Karber. The LC50 value for diesel-based emulsion of 12 ppm was quite low, indicating a high toxicity level. The fishes died within 2 h of exposure to 100 ppm concentration, in lower concentrations the mortality was slower in comparison and sub-lethal effects could be observed such as erratic swimming, loss of equilibrium and irregular respiration. In the triglyceride oil-based emulsions of Jatropha oil and palm oil, the mortality rate was half as compared to diesel-based emulsified acid exposure. The LC50 values for Jatropha and palm oil emulsions were 86.5 and 89.5 ppm respectively, indicating low toxic nature of the emulsified acids. The fishes did not have sudden changes in behavior apart from very rare irregular respiration problem in limited number of organisms at 100 and 70 ppm concentrations.

Core flooding

As presented in Tables 8 and 9 which highlight the state of the cores before and after core flooding tests, the core acidized with Jatropha curcas oil-based emulsified acid had a more drastic effect on permeability, having a permeability ratio (final K/initial K) of 227.2 than the core acidized with diesel-based emulsion having a permeability ratio of 155.3 (Sayed et al. 2012). This is presumed to be because of higher viscosity provided by Jatropha oil due to which the retardation effect is much more effective for generating larger number of permeable zones by branching out from the original fluid conduit path rather than just catering to one permeable zone (Markey et al. 2014). In contrast diesel oil due to lower viscosity has more dissolution reaction between the surface of the rock and emulsified acid, it does not cater to lower permeable zones (Tables 10, 11, 12).

A highly viscous fluid not only provides valuable retardation but also tends to spread throughout the core thus moving towards lower permeable zones. In contrast, stimulating fluids with lower viscosity tends to predominately invade the high permeable zones (Zakaria and Nasr-El-Din 2015). A high viscous emulsion indicates its droplet sizes to be small which provides an increase in stability of the emulsion (Al-Mutairi et al. 2009a), this in return provides emulsion acid solubility resistance against high temperature conditions. The core flooding experiment presented here also validates the results of the acid solubility API RP-40 test as well as the effect of droplet size conducted before (as shown in Table 4; Fig. 11, respectively). The Jatropha oil-based emulsified acid has a lower acid solubility percentage even with the increase in temperature, thus allowing acid to be consumed much slowly and steps up the stimulation process. Figure 14 shows the cores after exposed to acidization by Jatropha oil-based (a) and diesel oil-based (b) emulsified acids and the flushed out acids after acidizing.

Figures 15 and 16 show pressure drop profiles of cores acidized with Jatropha and diesel oil, respectively. Both figures indicate reaching the end of the core by the acidizing medium while creating the conduit. Both the cores achieved pressure drop nearly close to one another. However, diesel laced acid achieved higher pressure drops of 1.6 psi in comparison with Jatropha oil-based emulsion which achieved one peak pressure drop at 1.5 psi. This stipulates higher consumption of the diesel-based acid and possibility of increase residue production due to acid reactivity. Previous research observations indicate that this phenomena can prevent deep wormhole generation (Markey et al. 2014).

Conclusion

The tests conducted helped in concluding that triglyceride oils are sound replacements to diesel as an environmental friendly fluid for acidizing operations. Long carbon chain triglyceride oil such as that obtained from Jatropha curcas are more suitable than medium chain triglycerides like palm oil, this is because of the smaller droplet size Jatropha oil emulsion possess in comparison with palm oil-based emulsion thus providing with an increase in miscibility and thermal stability of the emulsion along with a more viscous fluid which is able to retard reactivity of acid with the rock formation, as seen in the experiments conducted, where Jatropha-based emulsion proved to be more effective. Moreover, the comparison of toxicity loads, has indicated both triglyceride oil-based emulsified acids to be more environmental friendly than diesel oil-based emulsion.

After evaluating various properties of the tested emulsions against diesel oil-based emulsion, Jatropha oil having an edge over palm oil was considered for core flooding. The core flooding results highlighted high prospect of Jatropha oil-based emulsion as a productive green acidizing fluid, giving a higher permeability ratio than diesel-based emulsion.

Thus after observing the various properties of Jatropha oil-based emulsified acids in comparison with the diesel oil-based emulsified acid it can be concluded that Jatropha oil can be a viable candidate for substituting diesel oil in emulsified acids used for matrix-acidizing purposes. Not only is it environmental friendly courtesy of having a very low toxicity, it has a high fatty acid content which provides the necessary properties such as suitable viscosity, stability, retardation and mobility favorable for effective matrix acidizing.

References

Abdullah K, Malloy T, Stenstrom MK, Suffet IH (2016) Toxicity of acidization fluids used in california oil exploration. Taylor & Francis, London

Adedeji OB, Adedeji AO, Adeyemo OK, Agbede SA (2008) Acute toxicity of diazinon to the African catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Afr J Biotechnol 7:651–654

Adesina F, Anthony A, Gbadegesin A et al (2012) Environmental impact evaluation of a safe drilling mud. In: SPE Middle East Health, Safety, Security, and Environment Conference and Exhibition, SPE-152865-MS. Abu Dhabi, UAE, pp 1–9

Al-Anazi HA, Nasr-El-Din HA, Mohamed SK (1998) Stimulation of tight carbonate reservoirs using acid-in-diesel emulsions: field application. In: SPE international symposium on formation damage control, SPE-39418-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, pp 9–17

Al-Mutairi SH, Nasr-El-Din HA, Hill AD (2009a) Droplet size analysis of emulsified acid. In: SPE Saudi Arabia Section Technical Symposium, SPE-126155-MS, pp 1–13

Al-Mutairi SH, Nasr-El-Din HA, Hill AD, Al-Aamri A (2009b) Effect of droplet size on the reaction kinetics of emulsified acid with calcite. SPE J 14:606–616. https://doi.org/10.2118/112454-PA

Amanullah M (2005) Physio-chemical characterisation of vegetable oils and preliminary test results of vegetable oil-based muds. SPE/IADC Middle East Drill Technol Conf Exhib. https://doi.org/10.2118/97008-MS

American Petroleum Institute (1998) Recommended practices for core analysis RP-40, p 236

Anand A, Meenakshi M (2011) Compatibility of metals in jatropha oil. Corros 8230

Bazin B, Abdulahad G (1999) Experimental investigation of some properties of emulsified acid systems for stimulation of carbonate formations. In: SPE Middle East Oil Show, SPE-53237-MS, Bahrain, pp 1–10

Bishop J, Bohlen S (2014) EPA letter to California State Water Resources Control Board and California Department of Conservation—12/22/2014

Buijse MA, Domelen MS Van (1998) Novel application of emulsified acids to matrix stimulation of heterogeneous formations. In: SPE international symposium on formation damage control, SPE-39583-MS, pp 601–611

Cairns AJ, Al-Muntasheri GA, Sayed M et al (2016) Targeting enhanced production through deep carbonate stimulation: stabilized acid emulsions. In: SPE international conference and exhibition on formation damage control. Society of Petroleum Engineers, Lafayette, Louisiana, USA, pp 1–24

Chan KS, Flores JC, Fraser G et al (2006) Oilfield chemistry at thermal extremes. Oilf Rev 18:4–17

Chempro Company (2017) Table for fatty acid composition of some major vegetable oils. In: TOP-TOPNOTCH Technol. Prod. OILS FATS. https://www.chempro.in/fattyacid.htm

Congress US (2005) Energy policy act of 2005, Subtitle C, Sect. 322

Croda Europe Ltd (2009) Span and tween. In: Croda Ind Chem. http://chemagent.ru/prodavtsy/download/849/968/19, pp 1–6

Dede EB, Kaglo HD (2001) Aqua-toxicological effects of water soluble fractions (WSF) of diesel fuel on O. Niloticus fingerlings. J Appl Sci Environ Manag 5:93–96

Fadairo A, Orodu D, Falode O (2013) Investigating the carrying capacity and the effect of drilling cutting on rheological properties of jatropha oil based mud. In: SPE Nigeria annual international conference and exhibition, pp 1–8

Guidry GS, Ruiz GA, Saxon A (1989) SXE/N2 matrix acidizing. In: SPE Middle East Oil Technical Conference and Exhibition, SPE-17951-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, Manama, Bahrain, pp 1–10

Hoefner ML, Fogler HS (1987) Role of acid diffusion in matrix acidizing of carbonates. J Pet Technol 39:203–208. https://doi.org/10.2118/13564-pa

Horiba Instruments I (2016) A guidebook to particle size analysis. In: Distribution. https://www.horiba.com/fileadmin/uploads/Scientific/Documents/PSA/PSA_Guidebook.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2017

Jeirani Z, Sp E, Jan BM, Ali BS (2006) A novel effective triglycer ride micro emulsion for chemical flooding (SPE158301). In: SPE Asia Pacific Oil and gas conference and exhibition

Karasinghe NU, Liyanage PJ, Cai J et al (2016) New surfactants and co-solvents increase oil recovery and reduce cost. SPE improved oil recovery conference held Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA, 11–13 April 2016, pp 1–34. https://doi.org/10.2118/179702-MS

Kärber G (1931) Beitrag zur kollektiven Behandlung pharmakologischer Reihenversuche. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Exp Pathol Pharmakol 162:480–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01863914

Koushki M, Nahidi M, Cheraghali F (2015) Physico-chemical properties, fatty acid profile and nutrition in palm oil. J Paramed Sci Summer 6:2008–4978. https://doi.org/10.22037/jps.v6i3.9772

S Majidaie, M Muhammad, IM Tan et al (2012) Non-petrochemical surfactant for enhanced oil recovery (SPE 153493). SPE EOR Conference at Oil and Gas West Asia

Malarvizhi S, Shyamala R, Papavinasam S (2015) Assessment of microbiologically influenced corrosion of metals in biodiesel from Jatropha curcas. NACE International—CORROSION 2015 Conference and Expo 2015

Markey F, Betz T, Gutaples J et al (2014) Examining innovative techniques for matrix acidizing in tight carbonate formations to minimize damage to equipment and environment. In: Proceedings of 2nd unconventional resources technology conference, pp 1–11. https://doi.org/10.15530/urtec-2014-1935101

Mofijur M, Masjuki HH, Kalam MA et al (2012) Prospects of biodiesel from Jatropha in Malaysia. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 16:5007–5020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.05.010

Mohadyaldinn ME, Azad N, Kalam A (2017) Evaluation of jatropha curcas oil as corrosion inhibitor of CO 2 corrosion in petroleum production environment. J Appl Environ Biol Sci 7:28–34

Mumtaz M, Tan IM, Mushtaq M (2015) Synergistic effects of surfactants mixture for foam stability measurements for enhanced oil recovery applications (SPE-178475-MS). SPE Saudi Arabia section annual technical symposium and exhibition 2015

Nasr-El-Din HA, Al-Anazi HA, Mohamed SK (1999) Stimulation of water disposal wells using acid-in- diesel emulsion: case histories. In: SPE international symposium on oilfield chemistry, SPE-50739-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, Houston, Texas, USA, pp 1–12

Nasr-El-Din HA, Solares JR, Al-Mutairi SH, Mahoney MD (2001) Field application of emulsified acid-based system to stimulate deep, sour gas reservoirs in Saudi Arabia. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, SPE-71693-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, New Orleans, LA, USA, pp 1–16

Nasr-el-din HA, Texas A, Al-dirweesh S, Aramco S (2008) Development and field application of a new, highly stable emulsified acid. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, SPE-115926-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, Denver, Colarado, USA, pp 1–11

Navarrete RC, Holms BA, McConnell SB, Linton DE (1998) Emulsified acid enhances well production in high-temperature carbonate formations. In: SPE European Petroleum conference, SPE-0699-0047-JPT. Society of Petroleum Engineers, Hague, Netherland, pp 391–406

Navarrete RC, Holms BA, McConnell SB, Linton DE (2000) Laboratory, theoretical, and field studies of emulsified acid treatments in high-temperature carbonate formations. SPE Prod Facil 15:96–106

Nierode DE, Kruk KF (1973) An evaluation of acid fluid loss additives, retarded acids, and acidized fracture conductivity. SPE 4549-MS. J Pet Technol. https://doi.org/10.2118/4549-MS

Nordiyana MSW, Munawar K, Jan BM et al (2016) Formation and phase behavior of Winsor type III Jatropha curcas—based microemulsion systems. J Surfact Deterg 19:701–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11743-016-1814-y

Olajire AA (2014) The petroleum industry and environmental challenges. J Pet Environ Biotechnol 5:1–19. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7463.1000186

Okeke EO, National N, Corporation P (2013) Modelling the transient behaviors of the kinetics in the transesterification of palm oils reveals prospects for customization of esters for drilling fluids formulation. In: IPTC 16573

Opedal NVDT, Sørland G, Sjöblom J (2009) Methods for droplet size distribution determination of water-in-oil emulsions using low-field NMR. Diffus Fundam 9:1–29

Portier S, André L, Vuataz F (2007) Review on chemical stimulation techniques in oil industry and applications to geothermal systems. Centre for Geothermal Research, Neuchâtel

Pramanik K (2003) Properties and use of jatropha curcas oil and diesel fuel blends in compression ignition engine. Renew Energy 28:239–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-1481(02)00027-7

Robert JA, Crowe CW (2000) Chap. 17: carbonate acidizing design. In: Michael JE, Kenneth GN (eds) Reservior stimulation, 3rd ed. Wiley, Oxford, pp 17-1–17-15

Rostron P, Kasshanna S, Aoudi H (2017) Novel synthesis and characterization of vegetable oil derived corrosion inhibitors. In: NACE international corrosion conference and expo 2017, pp 3–4

Sarma DK, Agarwal P, Rao E, Kumar P (2007) Development of a deep-penetrating emulsified acid and its application in a carbonate reservoir. In: 15th SPE Middle East Oil and Gas Show and conference, SPE-05502-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, Bahrain, pp 1–7

Sayed MA, Zakaria A, Nasr-El-Din HA et al (2012) Core flood study of a new emulsified acid with reservoir cores. SPE Int Prod Oper Conf Exhib SPE-157310-MS 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2118/157310-MS

Sayed MA, Nasr-El-Din HA, Nasrabadi H (2013) Reaction of emulsified acids with dolomite. J Can Pet Technol 52:164–175

Schlumberger (2007) Carbonate reservoirs: meeting unique challenges to maximize recovery. Schlumberger, Houston, pp 1–12

Sidaoui Z, Sultan AS, Qiu X (2016) Viscoelastic properties of novel emulsified acid using waste oil: effect of emulsifier concentration, mixing speed and temperature. In: SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition, SPE-182845-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, Dammam, Saudi Arabia, pp 1–11

Siddiqui S, Nasr-El-Din HA, Khamees AA (2006) Wormhole initiation and propagation of emulsified acid in carbonate cores using computerized tomography. J Pet Sci Eng 54:93–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2006.08.005

Soffian NM, Jeirani Z, Hisham B et al (2015) Jatropha based microemulsion efficiency screening study for enhanced oil recovery. Aust J Basic Appl Sci 9:118–125

The European Pharmacopoeia (2008) 2.2.10. Viscosity—rotating viscometer method

Update D, Rufli H, Changes T (2014) OECD guideline for testing of chemicals draft revised version fish, acute toxicity test

Weber CI, Environmental Monitoring Systems Laboratory (Cincinnati O, Agency USEP) (1991) Methods for measuring the acute toxicity of effluents and receiving waters to freshwater and marine organisms. Epa-600/4-90-027 1–275

Williams BB, Gidley JLS (1979a) Acid types and the chemistry of their reactions. In: Acidizing fundamentals. Society of Petroleum Engineers of AIME, pp 10–17

Williams BB, Gidley JLS (1979b) Chap. 10: matrix acidizing of carbonates. In: Acidizing fundamentals. Society of Petroleum Engineers of AIME, pp 86–91

Xiong C, Zhou F, Liu Y et al (2010) Application and study of acid technique using novel selective emulsified acid system. In: CPS/SPE international oil & gas conference and exhibition, SPE-131216-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, Beijing, China, pp 4–9

Yegin C, Singh BP, Zhang M et al (2017) Next-generation displacement fluids for enhanced oil recovery. SPE Oil Gas India Conf Exhib. https://doi.org/10.2118/185352-MS

Zakaria AS, Nasr-El-Din HA (2015) Application of novel polymer assisted emulsified acid system improves the efficiency of carbonate acidizing. In: SPE international symposium on oil field chemistry, SPE-173711-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, Woodlands, USA, pp 1–23

Acknowledgements

This work was fully supported by Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS (STIRF no. 0153AA-D97) and University of Khartoum (no. 0153AB-M28).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yousufi, M.M., Elhaj, M.E.M., Moniruzzaman, M. et al. Synthesis and evaluation of Jatropha oil-based emulsified acids for matrix acidizing of carbonate rocks. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 9, 1119–1133 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-018-0530-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-018-0530-8