Abstract

The aim of this study is to assess the accuracy of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) method in estimating the porosity and permeability in a carbonate reservoir located in south of Iran. In this study, 26 carbonate samples were selected and common core and NMR experiments were performed. Comparison of core and NMR porosity showed that NMR method is very accurate for estimation of porosity. However, after comparison of core and NMR permeability, it was found that NMR permeability estimation cannot be used with the common coefficients since they are calibrated in the clastic reservoirs. Therefore, it is necessary to modify coefficients in the permeability models of the considered reservoirs. For this purpose, 16 samples were selected to develop the model, and 10 samples for evaluating the accuracy of the model. In this study, free-fluid and mean T2 models were two main models for permeability estimation using NMR method. Coefficients of the two above-mentioned models were modified in terms of maximizing the coefficient of determination of core permeability and calculated permeability using NMR permeability models. The proposed models were used to estimate permeability in 10 other samples for verifying the reliability of models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Porosity indicates the amount of pore spaces in the rocks; and permeability represents the capacity of rocks to transmit fluids. Determination of the two aforementioned petrophysical parameters have an undeniable role in evaluation of reservoir rocks, consequently, planning for the development and production of the oil field. It is not difficult to determine the porosity of rocks directly in the laboratory, and it can be done in different ways. But determination of the permeability of rocks is difficult for various reasons such as high cost, time consuming and lack of enough samples. Due to the limitations of direct measurement of permeability, researchers around the world have made many attempts to estimate permeability using indirect methods. Various models and relations have provided to measure the permeability based on other parameters of reservoir rocks such as porosity (Neuzil 1994) specific surface area (Kozeny 1927), grain geometry (Schwartz and Banavar 1989), shape of pores (Yang and Aplin 1998) and grain size (Yang and Aplin 2010). The advantage of proposed relations is the high precision of measurement; and their main drawback is the necessity of having the samples and doing stringent laboratory testing. Unfortunately, in many cases, the use of these relations is associated with serious problems for various reasons, such as the lack of access to samples (especially in horizontal wells), high cost of doing experiments, as well as its lengthy procedure.

NMR technology (in laboratory and well logging) has had many applications in the oil industry from 1990 onwards, particularly for determining various parameters of rock and fluid such as porosity, fluid type, pore size distribution, and permeability (Kenyon 1992; Kleinberg et al. 1993; Kenyon et al. 1995a, b; Kleinberg 1996; Straley et al. 1997; Coates et al. 1999; Al-Mahrooqi et al. 2003; Alvarado et al. 2003; Westphal et al. 2005). NMR technology is able to directly measure porosity; but it cannot measure permeability directly. Therefore, a few models have been presented to estimate permeability (Coates et al. 1999). NMR technology has been studied well in the sandstones; therefore, it is possible to determine different parameters such as porosity, Bulk Volume Movable (BVM), Bulk Volume Irreducible (BVI) and permeability in sandstones (Ehrlich et al. 1991; Chang et al. 1994; Kenyon et al. 1995a, b). However, the situation is different in carbonates; and it is not possible to estimate parameters, in particular permeability, in these kind of rocks. There are two main reasons for this issue. One is the complexities inherent in the type and structure of the pore spaces, and the other, is the lack of sufficient study on carbonates for developing permeability models through laboratory experiments (Kaufman 1994; Lucia 1995; Amabeoku et al. 2001; Westphal et al. 2005).

Kenyon et al. (1995a, b) conducted a laboratory study of NMR and its relation to depositional texture and petrophysical properties in the Thamama carbonate group of Mubarraz field. Various models were used to estimate permeability, indicating that coefficients m and n in Eqs. 3 and 4 must be changed, in the first step. Second, constant coefficients of these models are smaller in carbonates than in the sandstones. Third, NMR permeability model with parameter transverse relaxation time (T2), gives better results alone compared to the Schlumberger Doll Research (SDR) model with routine coefficients (\({\phi ^4} \cdot T_{{2{\text{gm}}}}^{2}\)) in samples with high permeability. Fourth, in the models where T2 parameter is present in a way, give better results compared to the models where only porosity contributes.

Allen et al. (2001) divided carbonate samples into 4 groups based on the ratio of pore throat sorting to T2 and tested SDR model for the estimation of permeability. The results showed that permeability was associated with the square of porosity; and power of T2 cannot be changed as well. The value of correction coefficients can be considered constant in all samples. The important point is that the reduction of value of coefficient of porosity from 4, which is used in sandstones (Straley et al. 1997), to 2 in the carbonates indicates that with reduced porosity, pore networks unusually have a good relation with each other. In this research, the free-fluid model has not been examined well, and its capacity to estimate permeability in carbonates has not been investigated. Moreover, the assumption of the impossibility of changes in T2 can also be discussed.

Amabeoku et al. (2001) have conducted a research on applying Timur-Coates (TC) and SDR models in carbonate rocks and setting parameters of permeability models through laboratory studies. They provided 3 relations with different coefficients for 3 different wells; but in the model corrected for TC, the value of routine cutoff T2 (T2c) (100 ms) was used, and the values of BVI and BVM were determined accordingly. However, the T2 values for carbonates should be determined using NMR experiments in two modes of 100% saturation and residual saturation in order the value of producible fluid (BVM) and non-producible fluid (BVI) to be determined precisely.

Westphal et al. (2005) classified carbonate samples based on the pore types (primary and secondary) and used TC and SDR models as unchanged, with no correction in their coefficients. The results showed that well-related pores (interparticle and intercrystalline pores) had more proper results compared with unrelated or isolated pores (moldic, vugs and intraparticle pores). To achieve better results, they found it necessary to correct the models with experimental data.

Daigle and Dugan (2009, 2011) conducted studies on determining the correction coefficient of SDR model using other parameters such as gamma log and physical properties of rocks (Grain size, specific surface, porosity, magnetic susceptibility, grain density, and surface relaxivity) and showed that the value of correction coefficient in the SDR model can be determined using above methods, and thereby permeability can be estimated by SDR model, with routine coefficients. In this study, only SDR model was discussed; and the model coefficients were announced without correction.

Samples used in the present study were mainly moldic, vuggy and intraparticle porosity type. It tried to do necessary examinations on the accuracy of routine models used to predict permeability; and if necessary, to make needed corrections and adjustments to provide an appropriate model for carbonate rocks with low permeability.

Geological description

Asmari Formation

The Oligo-Miocene Asmari Formation was firstly defined by Thomas (1950) and then by James and Wynd (1965). In its type section (Kuh-e-Asmari), the formation consists of fossiliferous limestone with sandstone tongues in the lower part. Toward SW from type locality, these carbonates change laterally to mixed clastic-carbonate and sandstone facies (Ahwaz Member). In addition, a thick anhydrite unit (Kalhur Member) is recognized in the south of Lurestan province within the Asmari carbonates. Depositional history and regional stratigraphic architecture of this formation are reviewed by Ehrenberg et al. (2006) and Van Buchem et al. (2010).

Burgan Formation

The Burgan Formation, Lower Cretaceous (Albian) sands and shales, is lateral equivalent of the Kazhdumi Formation in the northwestern side of the Persian Gulf. The formation and its equivalents (such as Nahr Umar Formation; Safaniya and Khafji Members) form important reservoir rock in several supergiant and many giant oil fields (Alsharhan 1991, 1994; Al-Eidan et al. 2001; Strohmenger et al. 2006; Van Buchem et al. 2010). The Great Burgan Field in the Kuwait has been ranked as the world’s second largest oil field (after Ghawar field) and mainly produces from the Burgan clastics. As well as, many oil fields have been discovered from these intervals in the Arabian countries (Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE and Oman) and also Iran (Alsharhan 1994). The Burgan Formation was introduced and described first by Owen and Nasr (1958) and it consists of several tens to a few hundred of meters of sands, shale, ooid ironstone and some limestone (Alsharhan 1994; Van Buchem et al. 2010).

Dariyan Formation

The Aptian-aged Dariyan Formation, known as Orbitolina Limestone, is one of the most important petroleum reservoirs in the Dezful Embayment and Persian Gulf areas (Motiei 1995; Ghazban 2007). Firstly, James and Wynd (1965) defined this formation in the Kuh-e-Gadvan. The formation belongs to the Khami Group and composed mainly of Orbitolina-rich carbonates. This formation has been divided into two informal units: Lower and Upper Dariyan. Unlike its equivalent in Arabian countries (Shuaiba Formation), the Dariyan Formation is not well studied and documented in the Zagros area of south and southwest Iran (Alsharhan 1985; Alsharhan et al. 2000).

Ghadvan Formation

The Gadvan Formation (type section in Kuh-e-Gadvan), is dominantly composed of alternating marls and shallow-water limestones, including a limestone marker bed in the upper part that so called Khalij (Dictyoconnus arabicus or Montseciella arabicus) member (James and Wynd 1965; Schroeder et al. 2010; Van Buchem et al. 2010). It is respectively overlaid and underlined by the Dariyan (Shuaiba) and Fahliyan (Yamama) Formations, with gradual boundaries. Previously, the age of formation was thought to range from the Barremian to Aptian. Van Buchem et al. (2010) revised age of this formation to the Barremian, based on benthic foraminifera, ammonites, planktonic foraminifera and carbon isotope curves (Vincent et al. 2010).

Yamama Formation

The Yamama Formation, from Thamama group in Arabian countries (Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Qatar), is Neocomian limestones between the dense Sulaiy limestone below and the Buwaib or Ratawi Formations above (Steineke and Bramkamp 1952; Sadooni 1993; Shebl and Alshahran 1994; Nairn and Alsharhan 1997; Alsharhan et al. 2000). Upper and lower contacts of this formation are conformable in many locations. It can be correlated with Minagish Formation in Kuwait, Habashan Formation in UAE, and Salil Formation in Oman. This formation is equivalent of the Fahliyan Formation (Khami group) in the onshore Zagros (James and Wynd 1965). The Yamama Formation and its equivalents produce oil (or represent oil show) in the South Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar and UAE (Nairn and Alsharhan 1997).

Sulaiy Formation

There are few published descriptions of the Tithonian–Valanginian Sulaiy Formation in the literature. The formation and its lithostratigraphic equivalents are among the best source rocks in southern Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and southwest Iran (Beydoun 1991; Nairn and Alsharhan 1997; Saad and Goff 2006; Al-Ameri et al. 2009). Owing to geological location and formation similarity, the nomenclature used here is borrowed from the Saudi stratigraphic naming. The Makhul and Garau Formations are lithostratigraphic equivalents of this formation in the Arabian and Iranian territories, respectively. Based on the existing information, the Sulaiy Formation was first defined by Steineke and Bramkamp (1952). Powers et al. (1966) re-described the formation in terms of occurrence, thickness, lithological character, nature of contacts, paleontology and age, and also economic aspects. They indicated that this formation is lithologically uniform and is composed mainly of tan, chalky, massive bedded, aphanitic limestone.

Fundamentals

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

The phenomenon of nuclear magnetic resonance occurs in the atoms with an odd number of protons or neutrons. Protons and neutrons rotate around their axis. When the number of neutrons and protons are equal, rotations are neutralized with each other, and there will be no longer a spinning nucleus. But the nucleus of atoms with disparities in the number of protons and neutrons, rotates around its axis and therefore, according to Faraday’s law, they will be converted into a magnetic dipole. Normally, orientation of these dipoles is random, but in the presence of an external constant magnetic field (B0), bipolar is polarized and is placed in line with the B0 field. The vector sum of bipolar is the mass magnetization (M0) which is the first step in creating nuclear magnetic resonance. In addition to causing polarization, application of B0 field causes the nuclei to have a precession around B0 with a specific frequency (Larmor). Larmor frequency varies for different nuclei and it is the basis for creating a resonance effect. Because by applying oscillating magnetic field (B1) with specified Larmor frequency, which is the larmor frequency of hydrogen nucleus in NMR studies, nuclei are deflected from B0 and do in-phase precession in the transverse plane. The phenomenon causes resonance signal and its recording in the coils, which are located in the transverse plane. By cutting off the oscillating field, the nuclei begin to return to the original relaxation state. This phenomenon is characterized by longitudinal relaxation time (T1) and transversal relaxation time (T2); which are the output of nuclear magnetic resonance test. In NMR experiments, due to the rapid decay of the signal, resonance pulse sequence is applied, so that the desired parameters can be recorded (Coates et al. 1999).

In general, there are three types of relaxation: bulk relaxation, diffusion-induced relaxation, and surface relaxation. Due to the relationship between the surface relaxation and the pore size, conditions in the laboratory is designed and provided in such a way that the surface relaxation is the dominant mechanism; so that the obtained time T2 represents the pores size. Therefore, having distribution T2 as the output of resonance experiment, the pores size distribution can be obtained (Kleinberg et al. 1994; Coates et al. 1999).

NMR permeability models

NMR permeability estimation models have been developed mainly through the study of sandstones (Coates et al. 1999). TC model (Timur 1968; Coates and Denoo 1981; Coates et al. 1991) (Eq. 1) and SDR model (Kenyon et al. 1988) (Eq. 2) are among two main models of NMR permeability estimation models.

where k is permeability (millidarcy-md), φ is porosity (m3/m3), BVM is producible part of porosity (m3/m3), BVI is non-producible part of porosity (m3/m3), C is the formation-dependent correction coefficient (md−0.25), T2gm is geometric mean of the T2 distribution (ms), A is the formation-dependent correction coefficient (md ms−2). These models can be rewritten in parametric form (Eqs. 3 and 4) (Amabeoku et al. 2001).

The remarkable point is that the dimensions of correction coefficients C and A are dependent on coefficients m and n (in Eqs. 3 and 4).

Materials and methods

The present study was conducted on a field located in the northwest of the Persian Gulf. The studied samples were selected from different formations, and a total of 26 samples (16 samples for modeling and 10 samples to test the accuracy of models) were studied (Table 1).

Macroscopic and microscopic tests were conducted on samples; then lithology, facies, and type of pores were determined, and in general, characterization of samples was performed. The studied formations included Asmari, Burgan, Dariyan, Gadvan, Yamama, and Solaiy. Porosity ranged from 2.47 to 33.76% and permeability ranged from 0.00013 to 18.37 md. Pores were also of vuggy, fine pores, intraparticle and moldic type, detailed information of which is given in Table 2.

Routine core analysis

The spectral gamma logging was first performed on the cores and the results were compared with gamma logging data to depth matching. After preparation of cores, samples were prepared and cleaned in the Soxhlet using toluene and methanol. The cleaned samples were dried under the temperature of 90 °C; and their grain density, porosity and permeability were measured.

NMR experiment

Nuclear magnetic resonance device used in this study works under the following conditions:

-

Ambient temperature of 5–35 °C

-

Humidity less than 80%

-

Atmospheric pressure of 84–107 kPa

-

220 V power supply and (1 ± 50) Hz

-

The time needed to prepare to work less than 2 h

After NMR experiment, the device output which is a resonance signal decreasing curve is obtained. Then the values of porosity and pore size distribution are measured using the software embedded in the device.

After above-mentioned common core tests, the steps necessary for the preparation of samples were performed for testing nuclear magnetic resonance. For this purpose, samples were cleaned with xylene and methanol in the Soxhlet device and saturated with salt water (brine). Then, the nuclear magnetic resonance experiment at 100% saturation and data analysis were performed and T2 distribution graph was obtained as in Fig. 1.

In the next step, for testing nuclear magnetic resonance in a state of residual saturation, the samples were placed in centrifuge, thus samples with residual saturation were obtained, and nuclear magnetic resonance experiment was performed in the state of residual saturation. After determining the distribution graph T2 in residual saturation as in Fig. 2, the necessary steps to determine the exact T2c was performed for each sample to examine incremental graph T2 in the two states of 100% saturation and residual saturation (see Fig. 3).

After determining the value of T2c for the samples, given the importance of the parameters of BVM, BVI and T2gm in permeability estimation models TC and SDR, these values were calculated for each sample as in Fig. 4. It should be noted that normally in sandstones and carbonates, the values of 33 and 92 ms are used for T2c, respectively (Straley et al. 1997; Westphal et al. 2005; Yao et al. 2010). However, in this study, to increase the accuracy of the models, values of T2c for each sample were determined through comparing the NMR results in both saturated and unsaturated states; Then by having a T2c value for each sample, the T2 distribution graph for each sample was divided into two parts of BVM and BVI, and their values were calculated for each sample. The results of analyzing the porosity and permeability estimation models are proposed bellow.

Results and discussion

Presence of very low permeability (between 0 and 1 md) samples in this study causes that comparison between the core permeability and permeability of models (in the ordinary scale) will be encountered with error in calculating the coefficient of determination. The influence of very low permeability values is very low in comparison with larger amounts in the coefficient of determination. Therefore, the logarithm of permeability results was used for comparing core and model permeabilities, to display the errors that occur at low levels whose influence on the coefficient of determination is not shown well.

Porosity

Porosity is one of the most important parameters that is paramount of importance in the study of reservoirs and plays significant role in permeability models. For this reason, it should be specified to what extent is the accuracy of NMR method for determining porosity in the samples. In the NMR experiment results, the surface area under T2 distribution graph can be considered as the porosity for the samples (Coates et al. 1999). Thus, porosity for 26 carbonate samples studied in the laboratory was measured using Helium Porosity method. Then, using nuclear magnetic resonance device, porosity of 26 samples were measured at 100% saturation mode. Regression analysis between the results of laboratory-obtained porosity and NMR-obtained porosity showed that a good relationship is between the porosities obtained using NMR method and porosities obtained using Helium technique (R2 = 0.95). Therefore, the porosity obtained by NMR method can be used in the estimations and calculations (see Fig. 5).

Studies on clean sandstones represent a good match between the NMR porosity and core porosity (helium porosity) which shows the error of about 1% (Coates et al. 1999). The studies conducted on sandstones, total porosity is equal to effective porosity due to the lack of the fine porosities. Comparison of helium porosity and NMR porosity in coals showed good accuracy of NMR method in measuring the porosity (Yao et al. 2010). In this study, based on the results obtained in comparison of the core porosity and NMR porosity, it was shown that NMR technique can be used for accurate estimation of porosity in the carbonate samples (see Fig. 5).

Permeability

As mentioned, NMR method gives indirect permeability. Equations provided in TC and SDR models (Eqs. 3 and 4) (Amabeoku et al. 2001), were used as the two main models for estimating permeability using NMR. Equations 1 and 2 were first used to estimate permeability for the aim of examining the accuracy of aforesaid equations with routine coefficients which are mainly provided for sandstones. Then, Eqs. 3 and 4 were used to estimate permeability, so that from 26 available samples, 16 samples were used to develop the model and correction of coefficients, and 10 samples were used to test the accuracy of the proposed models. Finally, the estimated permeability in different states was compared with core permeability measured in laboratory using Air Permeability method. These procedures are described below.

Routine mode

As mentioned, in this mode, Eqs. 1 and 2 were used as the models used to estimate permeability. In the following, the procedure and the conducted studies are provided in two models of TC and SDR.

TC model

The first step in estimating the permeability using TC model is to determine the correction coefficient of the Eq. 1 (C factor). To determine the amount of C, it is required to rewrite the Eq. 1 as follows (Coates et al. 1999):

As mentioned, correction coefficient C is formation dependent, and its value is considered to be 6.2 for sandstones (Coates et al. 1999). Thus, according to Eq. 5, using the proposed coefficients m = 4 and n = 2 for sandstones, diagram \(\phi \cdot \sqrt[2]{{\left( {\frac{{{\text{BVM}}}}{{{\text{BVI}}}}} \right)}}\) against \(\sqrt[4]{{{k_{{\text{core}}}}}}\) was drawn (with zero intercept), and the slope of the best linear fit of data represents the value of C. As mentioned, this value has been obtained as equal to 6.2 for sandstones (Coates et al. 1999). For the samples used in this study, the value of C should be determined with respect to the core data, measured permeability, and the results of NMR, as well as the values of BVM and BVI.

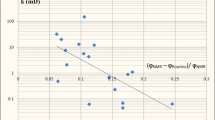

Finally, diagram \(\phi \cdot \sqrt[2]{{\left( {\frac{{{\text{BVM}}}}{{{\text{BVI}}}}} \right)}}\) against \(\sqrt[4]{{{k_{{\text{core}}}}}}\) was drawn (with zero intercept) and linear regression analysis was performed and the value of C was determined as in Fig. 6.

As is evident in Fig. 6, the value of coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.93) for the fitted equation is acceptable; therefore, this value of C (0.281) can be used for all samples.

Using the value of C in Eq. 1, the permeability of samples can be estimated using TC model, and the obtained values can be compared with the permeability values measured in the laboratory (see Fig. 7). As is shown in Fig. 7, coefficient of determination is equal to 0.79 between core and TC model permeabilities.

SDR model

To estimate the permeability using SDR model in routine mode (Eq. 2), the value of A should be calculated using core permeability data and geometric mean of transverse relaxation time (T2gm). To calculate the value of A, it is needed to put the value of permeability in Eq. 2 and draw diagram kcore against\({\phi ^4} \cdot T_{{2{\text{gm}}}}^{2}\). Then, the slope of the best linear fit of the data with zero intercept represents the value of A as in Fig. 8. According to the coefficient of determination 0.96, this value of A, i.e., 0.0939 can be used for the samples.

After determining the value of A, NMR permeability is calculated in the SDR model using Eq. 2 (see Fig. 9). As is evident in Fig. 9, there is not a good match between the results of core permeability and SDR model (R2 = 0.11).

Modified mode

As shown in the previous section, TC and SDR models with routine coefficients are not able to estimate permeability in the studied samples appropriately, and therefore, it is required to correct the coefficients. For this purpose, 26 studied samples were divided into two groups of 16 and 10.

The group with 16 samples was used for coefficient correction, and the group with 10 samples was used to test the accuracy of the corrected models. It should be noted that, the estimation of permeability is one of the main goals in this study, therefore, in modifying the models, non-linear fitting with criteria of maximizing the coefficient of determination between core permeability and the permeability obtained by the models was applied.

Modified TC model

As mentioned, in TC model, the determination of coefficient between calculated permeability and core permeability was used as an appropriate criterion, and the values of n and m (Eq. 3) were corrected to the extent that coefficient of determination of calculated permeability and core permeability to be maximized. Coefficient of determination of core permeability and TC permeability reached its maximum in the amount of 0.919; and the values of m and n were obtained equal to 3.9 and 0.51, respectively. The value of C was determined as equal to 0.222, with determination coefficient of 0.948 (see Figs. 10, 11). The modified TC model can be rewritten as follows (Eq. 6).

To determine the accuracy of Eq. 6 (modified TC model), the resulting model was used to estimate the permeability of the samples in the group with 10 samples. The coefficient of determination of calculated permeability and core permeability was equal to 0.918 which is a reasonable coefficient of determination as in Fig. 12.

Modified SDR model

Similar to the previous section, in SDR model, the determination coefficient between calculated permeability and core permeability was used as an appropriate criterion, and the values of n and m in Eq. (4) were changed to the extent that the selected criterion was maximized. The maximum coefficient of determination was equal to 0.965 and the values of 1.64 and 1.68 were obtained for m and n, respectively. Also value of 0.0216 for A (md ms1.68) was determined with a coefficient of determination of 0.955 as in Figs. 13 and 14. The following equation (the modified SDR model) was used to examine the accuracy of the model and to estimate the permeability of 10 samples specified for the tests.

The coefficient of determination for calculated permeability and core permeability is equal to 0.966 that is an appropriate value for the coefficient of determination (see Fig. 15).

Summary and conclusions

In this study it was shown that using NMR method, the porosity in the carbonate samples (with low permeability) can be estimated well. However, parameters of NMR permeability model have to be adjusted to the carbonate reservoir.

TC and SDR models, as the main models of NMR permeability, were examined as an example; and it was shown that these models (Eqs. 1 and 2) must be modified. The necessary corrections were made based on maximizing the coefficient of determination of core permeability and model permeability; and the modified models verified by samples specified for the test. The results of matching the core permeability and model permeability shows that the coefficient of determination in TC model increase from 0.79 to 0.918 and in SDR model increase from 0.11 to 0.966 which is proper ability of the models to estimate the permeability. In TC and SDR proposed model (in most samples) estimated permeability is higher than core permeability that shows, proposed models a little over-estimated permeability. This study showed that the permeability estimation models for the study area must be corrected to make sure that the results are reliable (see Eqs. 6 and 7). In this research, porosity of the carbonate samples with low permeability, was well estimated and shows the proper ability of NMR method for determining porosity in such samples (Fig. 5).

References

Al-Ameri TK et al (2009) Petroleum system analysis of the Mishrif reservoir in the Ratawi, Zubair, North and South Rumaila oil fields, southern Iraq. GeoArabia 14(4):91–108

Al-Eidan AJ et al (2001) Upper Burgan reservoir description, northern Kuwait: impact on reservoir development. GEOARABIA-MANAMA 6:179–208

Allen D et al (2001) The practical application of NMR logging in carbonates: 3 case studies. In: SPWLA 42nd annual logging symposium, society of petrophysicists and well-log analysts

Al-Mahrooqi S et al (2003) An investigation of the effect of wettability on NMR characteristics of sandstone rock and fluid systems. J Petrol Sci Eng 39(3):389–398

Alsharhan A (1985) Depositional environment, reservoir units evolution, and hydrocarbon habitat of Shuaiba formation, Lower Cretaceous, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. AAPG Bull 69(6):899–912

Alsharhan A (1991) Sedimentological interpretation of the Albian Nahr Umr Formation in the United Arab Emirates. Sediment Geol 73(3–4):317–327

Alsharhan A (1994) ALBIAN CLASTICS IN THE WESTERN ARABIAN GULF REGION: A SEDIMENTOLOGICAL AND PETROLEUM-GEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION. J Pet Geol 17(3):279–300

Alsharhan AS et al (2000) Stratigraphy, stable isotopes, and hydrocarbon potential of the Aptian Shuaiba Formation, UAE

Alvarado RJ et al (2003) Nuclear magnetic resonance logging while drilling. Oilfield Rev 15(2):40–51

Amabeoku MO et al (2001) Calibration of permeability derived from NMR Logs in carbonate reservoirs. SPE Middle East Oil Show, Society of Petroleum Engineers

Beydoun ZR (1991) Arabian plate hydrocarbon geology and potential

Chang D et al (1994) Effective porosity producible fluid and permeability in carbonates from Nmr logging. In: SPWLA 35th annual logging symposium, Society of Petrophysicists and Well-Log Analysts

Coates G, Denoo S (1981) The producibility answer product. Tech Rev 29(2):54–63

Coates GR et al (1991) The MRIL In Conoco 33-1 an investigation of a new magnetic resonance imaging log. In SPWLA 32nd annual logging symposium, Society of Petrophysicists and well-log analysts

Coates GR et al (1999) NMR logging: principles and applications. Houston: Haliburton Energy Services

Daigle H, Dugan B (2009) Extending NMR data for permeability estimation in fine-grained sediments. Mar Pet Geol 26(8):1419–1427

Daigle H, Dugan B (2011) An improved technique for computing permeability from NMR measurements in mudstones. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 116:B8

Ehrenberg S et al (2006) Porosity-permeability relationships in interlayered limestone-dolostone reservoirs. AAPG Bull 90(1):91–114

Ehrlich R et al (1991) Petrography and reservoir physics I: objective classification of reservoir porosity (1). AAPG Bull 75(10):1547–1562

Ghazban F (2007). Petroleum geology of the Persian Gulf. Iran: Tehran University and National Iranian Oil Company

James G, Wynd J (1965) Stratigraphic nomenclature of Iranian oil consortium agreement area. AAPG Bull 49(12):2182–2245

Kaufman J (1994) Numerical models of fluid flow in carbonate platforms: implications for dolomitization. J Sediment Res 64(1):128–139

Kenyon W (1992) Nuclear magnetic resonance as a petrophysical measurement. Int J Radiat Appl Instrum Part E Nuclear Geophys 6(2):153–171

Kenyon W et al (1988) A three-part study of NMR longitudinal relaxation properties of water-saturated sandstones. SPE Form Eval 3(03):622–636

Kenyon W et al (1995a) A laboratory study of nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation and its relation to depositional texture and petrophysical properties: carbonate Thamama Group, Mubarraz Field, Abu Dhabi. In: Middle East oil show & conference

Kenyon B et al (1995b) Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging—technology for the 21st century. Oilfield Rev 7(3):19–33

Kleinberg R (1996) Utility of NMR T2 distributions, connection with capillary pressure, clay effect, and determination of the surface relaxivity parameter ρ2. Magn Reson Imaging 14(7):761–767

Kleinberg R et al (1993) T1/T2 ratio and frequency dependence of NMR relaxation in porous sedimentary rocks. J Colloid Interface Sci 158(1):195–198

Kleinberg R et al (1994) Mechanism of NMR relaxation of fluids in rock. J Magn Reson Ser A 108(2):206–214

Kozeny J (1927) Uber kapillare Leitung der Wasser in Boden. Sitzungsber. Akad Wiss Wien 136:271–306

Lucia FJ (1995) Rock-fabric/petrophysical classification of carbonate pore space for reservoir characterization. AAPG Bull 79(9):1275–1300

Motiei H (1995) Petroleum geology of Zagros. Geological Survey of Iran (in Persian), p 1003

Nairn A, Alsharhan A (1997) Sedimentary basins and petroleum geology of the middle east, Elsevier, Amsterdam

Neuzil C (1994) How permeable are clays and shales?. Water Resources Res 30(2):145–150

Owen RMS, Nasr SN (1958) Stratigraphy of the Kuwait-Basra area. In: Habitat of oil american association petroleum geologist memoir, vol 1, pp 1252–1278

Powers R et al (1966) Geology of the Arabian Peninsula—sedimentary geology of Saudi Arabia: USG Survey Professional Paper. 560-D, Washington

Saad ZJ, Goff JC (2006) Geology of Iraq. Brno, Czech Republic

Sadooni FN (1993) Stratigraphic sequence, microfacies, and petroleum prospects of the Yamama Formation, Lower Cretaceous, southern Iraq. AAPG Bull 77(11):1971–1988

Schroeder R et al (2010) Revised orbitolinid biostratigraphic zonation for the Barremian–Aptian of the eastern Arabian Plate and implications for regional stratigraphic correlations. GeoArabia Spec Publ 4(1):49–96

Schwartz LM, Banavar JR (1989) Transport properties of disordered continuum systems. Phys Rev B 39(16):11965

Shebl H, Alshahran A (1994) Sedimentary facies and hydrocarbon potential of Berriasian-Hauterivian carbonates in central Arabia. Micropalaeontology and Hydrocarbon Exploration in the Middle East. Chapman & Hall, London, pp 159–175

Steineke M, Bramkamp R (1952) MESOZOIC ROCKS OF EASTERN SAUDI-ARABIA. AAPG BULLETIN-AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF PETROLEUM GEOLOGISTS, AMER ASSOC PETROLEUM GEOLOGIST 1444 S BOULDER AVE, PO BOX 979, TULSA, OK 74101

Straley C et al (1997) Core analysis by low-field NMR. Log Analyst 38:84–94

Strohmenger CJ et al (2006) Sequence stratigraphy and reservoir architecture of the Burgan and Mauddud formations. Lower Cretaceous), Kuwait

Thomas AN (1950). The Asmari Limestone of south-west Iran. In: Hobson GD (ed) International geological congress, London, part IV, pp 35–44

Timur A (1968) An investigation of permeability, porosity, and residual water saturation relationships. In: SPWLA 9th annual logging symposium. New Orleans, Louisiana, Society of Petrophysicists and Well-Log Analysts

Van Buchem F et al (2010) Regional stratigraphic architecture and reservoir types of the Oligo-Miocene deposits in the Dezful Embayment (Asmari and Pabdeh Formations) SW Iran. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 329(1): 219–263

Vincent B et al (2010) Carbon-isotope stratigraphy, biostratigraphy and organic matter distribution in the Aptian–Lower Albian successions of southwest Iran (Dariyan and Kazhdumi formations). GeoArabia Spec Publ 4(1):139–197

Westphal H et al (2005) NMR measurements in carbonate rocks: problems and an approach to a solution. Pure Appl Geophys 162(3):549–570

Yang Y, Aplin AC (1998) Influence of lithology and compaction on the pore size distribution and modelled permeability of some mudstones from the Norwegian margin. Mar Pet Geol 15(2):163–175

Yang Y, Aplin AC (2010) A permeability–porosity relationship for mudstones. Mar Pet Geol 27(8):1692–1697

Yao Y et al (2010) Petrophysical characterization of coals by low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Fuel 89(7):1371–1380

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) for supplying data for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aghda, S.M.F., Taslimi, M. & Fahimifar, A. Adjusting porosity and permeability estimation by nuclear magnetic resonance: a case study from a carbonate reservoir of south of Iran. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 8, 1113–1127 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-018-0474-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-018-0474-z