Abstract

Experimental studies have proved the ability of high-viscosity oil to display at flow the properties typical of non-Newtonian systems. The relationship between pressure gradient and rate of movement in real reservoirs may be non-linear due to the interaction of asphaltenes and resins, forming the plastic structure in the oil. The impact of the restructuring processes on the viscosity of the oil and the possibility of Darcy’s law violation are not considered in most of the known hydrodynamic simulations. The authors of the article justified the analytical model of the pseudo-stationary flow of non-linear viscoplastic oil to the vertical well with a random configuration of the drainage area. The article presents the results obtained using the model in real design, including the well test analysis. The result of the study is the choice of the system of reservoir stimulation, which allows effective regulation of the structural and mechanical properties of high-viscosity oil. The considered mathematical model is useful for small high-viscosity oil fields to calculate variants with vertical wells. It can help to justify well spacing, the feasibility of address increase in the pressure drawdown and the use of thermal methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays the production of high-viscosity oil is linked to global development prospects of the world fuel and energy complex. Making design and technological decisions to regulate high-viscosity oil field development require unconventional approaches. This is largely due to the ability of oil to display at flow the properties typical of non-Newtonian systems.

To model the stress–deformation behaviour of viscoplastic materials, different constitutive equations have been proposed. The complete descriptions of such models are available in many books (Wilkinson 1960; Bird et al. 1987; Carreau et al. 1997; Khasanov and Bulgakova 2003; Mirzadzhanzade et al. 2005; Chhabra and Richardson 2008; Basniev et al. 2012) and review papers (Bird et al. 1983; Chhabra et al. 2001; Mitsoulis 2007). Rheological studies established deviation from Newton’s law of viscous friction, namely the violation of the linear relationship between the shear stress τ and the shear strain rate γ, as a particular case—the existence of the critical shear stress (yield stress) τ 0. Such effects accompany the flow of viscoplastic fluid, prone to formation of internal solid-like structure which begins to break down when the stress increases. The most popular equations that have been used to describe oils with yield stress τ 0 are the Bingham, Casson and Herschel–Bulkley models (Bingham 1922; Casson 1959; Herschel and Bulkley 1926), i.e.

where μ is dynamic viscosity; n is the exponent that characterizes the measure of deviation of the fluid behaviour from Newton’s law; K is consistency index, determined experimentally.

Oil as viscoplastic fluid is characterized by rheological parameters: yield stress τ 0 and dynamic viscosity μ (or non-linearity parameters n and K). If the shear stress τ is less than the yield stress τ 0, the flow is absent, i.e. the shear strain rate γ = 0.

At zero yield stress τ 0, Eq. (3) is transformed into Ostwald–de-Waele relation

which is considered adequate for pseudo-plastic (n < 1) or dilatant (n > 1) types of flow.

In many cases, the relation of rheological parameters becomes more complicated, which gives reason to believe: the fluidity of viscoplastic media is the variable characteristic of the substance, as it depends on its strain rate (Bernadiner and Entov 1975; Khasanov and Bulgakova 2003).

The authors (Devlikamov et al. 1975) found experimentally and justified theoretically the fact that under non-linear viscoplastic oil possess, there are two critical shear stresses: the stress τ r , corresponding to the beginning of the destruction of the inner oil structure and the stress τ m , corresponding to its complete destruction. In this case, the oil flow is considered within a continuum (the volume of a capillary or a pore), and the restructuring processes taking place where the oil contacts with the wall of the channel, leading to the formation of marginal layers are ignored.

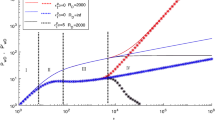

Instrumental studies of phase transitions in the reservoir fluids (Syunyaev et al. 1990; Revizskiy and Dyblenko 2002) have proved the existence of hierarchical levels of structural organization. Nano- and microstructures of different scale, present in the oil disperse systems, are able to interact with each other and realign under the influence of external factors. Successive states are characterized by different granularity, whereupon the oil should be considered as a dynamic system with complex rheological behaviour. The basic particles that control the process of structure formation in the oil are asphaltenes, resins and paraffin. Graphic constructions characterizing the most common types of stationary rheological fluid flow are shown in Fig. 1.

The diversity of permolecular structure types causes non-linear deviations in the behaviour of oil disperse systems not only from Newton’s law, but also from Darcy’s law. As shown by the flow experiments (Devlikamov et al. 1975; Khasanov and Bulgakova 2003; Gafarov and Shamaev 2005), in a porous medium at the pressure above the saturation pressure of the oil with gas and in the absence of an aqueous phase within a certain range of pressure gradients and rates of flow, the relation between these parameters for the structured oil becomes non-linear. The fact is noteworthy because the linearity of Darcy’s law is an approximation implemented in the vast majority of hydrodynamic simulators.

The rate of oil flow cannot obey linear Darcy’s law in case of a certain combination of thermobaric factors. The degree of non-Newtonian properties manifestation of non-linear viscoplastic oil depends on the permeability of the reservoir, the relation and component composition of the hydrocarbon phase—the presence of paraffin, asphaltenes, resins, nitrogen, methane and ethane.

In the popular model of “black oil”, the reservoir hydrocarbon system is regarded as a pseudo-binary mixture. The block of initial data on the properties of the oil component at the input to the model includes dependences on the PVT parameters. Such representation is not enough for high-viscosity oil with proved non-Newtonian properties, because in a real porous medium at the same pressure, structure-forming oil components can interact in very different ways, which is reflected in the distribution of seepage flow.

Geological conditions and laboratory experiment

Over the recent decades, in the Volga–Ural oil-producing region of Russia, there have been explored and brought into development the fields, many of which are deposits of oil with high viscosity (more than 30 mPa s). Among them, one can identify a separate group of fields located at the junction of the south-eastern and eastern edges of the Melekess Depression, the Soksky Saddle and the South-Tatar Arch.

The deposits in the south-eastern edge of the Melekess Depression (within the boundaries of the Samara Region) are located in the Upper Devonian–Tournaisian carbonate and terrigenous Visean oil and gas complexes. The oil of the productive reservoirs is heavy, sulphurous; its viscosity increases from the lower to the upper stratigraphic deposits. Percentagewise, the share of deposits of oil with a viscosity in the range of 30–80 mPa s for the Upper Devonian carbonate reservoirs is 29 %. For deposit reservoirs A4 and A5 of Bashkir–Serpukhov carbonate subcomplex, the lower limit of the viscosity exceeds 100 mPa s and a quarter of the oil deposits of the said subcomplex has a viscosity of over 400 mPa s. There is regular weighting of the oil up the section, with the increase in the content of resins, asphaltenes, paraffins and such elements as nickel and vanadium.

The viscosity and density of the oil of the productive deposits of the eastern edge of the Melekess Depression (within the boundaries of the Tatarstan Republic) are also increasing up the section in the direction from the bottom–up. The viscosity of the oil in the deposits of the middle and lower carbon ranges 56–204 mPa s, the lower carbon—30–140 mPa s, sometimes reaching 1000 mPa s. Asphaltenes content increases up the section from 17–23 % (Upper Devonian) to 30–43 % (carbon).

The deposits on the studied territory were formed at about the same time, under the influence of similar geological processes which probably accounts for the comparability of the rock collecting properties and parameters of the oil. According to some Russian scientists (Zaydelson et al. 1991), oil reserves in coal deposits were formed in the last stages of the Hercynian tectogenesis, but the Melekess Depression acquired its modern shape in the final stages of the alpine tectogenesis. Streams of thermal energy and migration of thermal waters in the bodies of sedimentary rocks had to activate processes of hydrocarbons oxidation and redistribution in deposits of some minerals. The fact should be noted that the most viscous oil (over 400 mPa s) is confined to Bashkirian deposits, which are characterized by a break in sedimentation.

It is logical to assume that due to the obvious similarity of filtering-capacitative properties, lithofacies characteristics of collecting rocks and parameters of reservoir fluids, non-Newtonian properties of high-viscosity oil discovered by special studies, will appear about the same. It can be assumed as a postulate that for analogous deposits, located in the Melekess Depression, the effect of these properties on the development process will be identical. Therefore, to describe the non-Newtonian flow of oil and the characteristic effects, one can use a single analytical model with the possibility of filling the block of input data on the basis of analogy, which greatly simplifies the modelling.

Figure 2 shows a graph of the flow rate dependence on the pressure gradient obtained in the course of experiments with the oil from reservoir A4 Strelovsky field on the equipment of the National University of the Mineral Resource “Gorniy” in the laboratory “Increase in Layer Oil Recovery”. Flow studies were conducted on a model consisting of natural core samples under the thermobaric conditions close to the reservoir ones. Determination of absolute permeability and porosity was carried out using automated permeameter–porosimeter AP-608 (Coretest Systems Corporation). Table 1 represents the results of measurement of filtering-capacitative properties. Laboratory studies were conducted on the flow equipment RPS-812 (Coretest Systems Corporation) at the temperatures of 26–45–70 °C in the steady flow mode.

The obtained dependences prove the existence of a non-linear relationship between the flow rate and the pressure gradient in the temperature range 26–45 °C. Increasing the temperature to 70 °C leads to a weakening of the effect. At lower temperatures, the experimental dependence obtained for Strelovsky oil field is typical of the non-linear viscoplastic fluid with two critical pressure gradients (Devlikamov et al. 1975). By analogy with the critical shear stresses τ r and τ m , the first critical pressure gradient H r corresponds to the beginning of the destruction of the oil inner structure and the second one H m —to its complete destruction. Meanwhile, the flow rate follows variations in viscosity—integral macroscopic rheological parameter, depending on the pressure gradient and peculiarities of the oil system restructure.

The values of the critical pressure gradients and variations of viscosity defined in the flow experiments simulating the flow of oil for the initial conditions of A4 layer of Strelovsky field are shown in Table 2.

The process of hydrodynamic modelling can use both the data of the flow experiment and generalized mathematical dependences linking the critical pressure gradients with yield stress and reservoir permeability of the formation. The authors (Devlikamov et al. 1975) suggest correlations to assess the values of the critical yield stresses by the known mass content of asphaltenes and resins in oil, of nitrogen, methane, ethane in the oil gas, adjusted for the layer temperature. The results of calculations, if they are extended over a group of similar fields, can be considered as an addition to the laboratory data.

Mathematical model of flow

The obtained results allowed to justify the analytical model of the pseudo-stationary flow of non-linear viscoplastic oil to the vertical well with a drainage area of random configuration. This model is a system of equations, which generally describes the process of the oil flow, showing the properties of non-linear viscoplastic fluid depending on the pressure drawdown ∆P (Olkhovskaya 2011):

In Eq. (5), ΔP m is the minimum pressure drawdown, under which the oil in the entire drainage area of the well will be filtered at a constant minimum viscosity μ m and with completely destroyed inner structure; ΔP n is the maximum pressure drawdown under which the oil in the entire drainage area of the well will be flowed at a constant maximum viscosity μ 0 and with undisturbed inner structure.

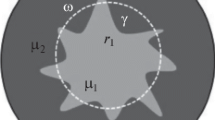

Parameter ω depends on form factor C A , calculated by Dietz (1965) and recalculated by Astaf’ev and Roters (2014), and is determined from the relation

Other symbols in Eq. (5): Q—well flow rate; k—absolute permeability; h—thickness of the productive reservoir; P k —the pressure on the external boundary of the flow area; P c —bottom hole pressure in the well; R k —the distance from the bottom of the hole to the external boundary of the flow area; R c —the radius of the well; H r and H m —two critical pressure gradients, ΔH = H m − H r ; r m —the distance from the well to the boundary, where the pressure gradient is H m ; r d—the distance from the well to the boundary, where the pressure gradient is equal to H r ; B n —oil volume factor; Δμ = μ 0 − μ m.

The physical meaning of Eq. (5) is as follows. Oil flow to the well occurs with variable viscosity, depending on the pressure gradient. In the nearest area to the well, which can be schematized as a circle equivalent in size and characterized by the radius r m , the oil is flowed with completely destroyed inner structure and constant minimum viscosity μ m. With moving away from the well and reduction of the pressure gradient, the oil structure becomes stronger and its viscosity increases. Outside the schematized circular area with r d radius, oil viscosity reaches its maximum value μ 0.

If in the entire flow area the pressure gradient exceeds the second critical pressure gradient (the complete structure destruction gradient) H m , the oil to be filtered with a minimum viscosity μ m, since the structure formed by the asphaltenes and resins, is destroyed. In fact, this effect can be achieved by the increase in pressure or temperature. In the first case, it means expansion of the area where the oil is filtered with a minimum viscosity; in the second case, it means reduction of the critical pressure gradients, which is proved experimentally and reflected mathematically in the correlation dependences.

The equivalent radii are related to the well flow rate with the following relations (Devlikamov et al. 1975):

The oil flow Q, characterized by constant viscosity μ, taking into account the impact of the external boundary of random form on the flow within the area A, is described by the equation (Olkhovskaya 2011):

Expressing the flow rate Q from formulas (7) and (8), and equating it to the right-hand side of Eq. (9), where the appropriate viscosity is substituted, adjusting for relation (6), we can obtain the equation for the calculation of pressures ∆P m и ∆P n .

If the calculated values ∆P m and ∆P n are greater than the pressure at the external boundary of the flow area P k , then under the existing geological and physical properties of the collector and the thermobaric condition of the deposit in the area of the studied well, the reservoir energy will not be enough even to overcome the first critical pressure gradient (the initial structure shift gradient) H r . The influence of structural and mechanical properties of oil on the flow will be maximized.

If the calculated ∆P n value is lower and ∆P m value is greater than the pressure at the external boundary of the flow area P k , the reservoir energy will be enough only to overcome the first critical pressure gradient H r . But the second critical pressure gradient H m will not be reached. Consequently, the influence of structural and mechanical properties of oil on the flow will be weakened, but not eliminated completely.

If the calculated values ∆P m and ∆P n are lower than the pressure at the P k , the reservoir energy will be enough to overcome both the first and the second critical pressure gradients. The influence of structural and mechanical properties of oil on the flow will be minimal.

Model (5) is a modification of the analytical equation of the steady flow of non-linear viscoplastic oil to a vertical well; it was derived for the first time by the authors (Devlikamov et al. 1975). It was obtained through a direct combination similar to the generalized macroscopic material balance equation (Dake 2001). Its difference is accounting for the influence of the geometric form of the external boundary of the flow area and the drainage area on the flow process, as well as the pseudo-stationary character of the flow of non-linear viscoplastic oil to the well in the “reservoir—well bottom zone” system.

The system of Eq. (5) can solve the following problems in modelling high-viscosity oil field development:

-

1.

to determine the thermobaric parameters of production, under which the influence of non-Newtonian properties of oil on the flow process will be eliminated;

-

2.

to optimize placement and density of the network of vertical wells—for the same purpose;

-

3.

to justify the value of reservoir permeability on the results of well flow studies with the provision of the pair of values of “flow rate—pressure”;

-

4.

to evaluate the degree of change in oil viscosity in the flow area with a known permeability;

-

5.

to improve the quality of well test analysis due to the choice of an adequate model of flow;

-

6.

to control the accuracy of production performance prediction by using hydrodynamic simulators, including Eclipse-100 (Schlumberger) software in the case of small deposits of high-viscosity oil and vertical wells.

Examples of practical use

Methods of hydrodynamic modelling and interpretation of results of field hydrodynamic well testing, taking into account non-Newtonian properties of oil, have been involved in the development design of high-viscosity oil fields, located in the Samara Region (Russia). The similarity of geological and physical characteristics and properties of oil proved by rheological research gives reason to believe most of these to be analogues of Strelovsky field.

Object 1

On the basis of calculations carried out for the oil deposit of high-permeability reservoir A4, it was found out that the maximum cost-effective well flow rate can be achieved at 7.5 MPa pressure without changing the initial reservoir temperature. With constant critical pressure gradients H r = 0.0024 MPa/m and H m = 0.0037 MPa/m, achieving the maximum projected well flow rate oil production is only possible by increasing pressure. Organization of thermal reservoir stimulation, as well as production stimulation using permeability increasing techniques, is not relevant.

The process of oil structure destruction in the studied reservoir begins with the application of pressure of ΔP n ≈ 1 MPa, and is fully completed at the pressure of ΔP m ≈ 2 MPa. It is predicted that the original oil structure will be completely destroyed if the distance between the borehole bottoms of the vertical wells is within 600 m over the entire developed area. The recommended variant of development provides the distance of 250–400 m between the wells, which is even more favourable in terms of regulating structural and mechanical properties of the oil.

Object 2

Figure 3 presents the results of calculations performed for oil deposits of reservoir A4, whose permeability is much lower. It was found that without the use of thermal methods, the minimum cost-effective oil flow rate will not be achieved under any pressure. At the reservoir temperature of 22 °C and the differential pressure increased to 10 MPa, the maximum flow rate will be only 1.8 m3 per day, as seen from Fig. 3. At the pressure of 7.76 MPa created during the field well tests, the minimum cost-effective flow rate, according to estimates, can be achieved by heating the reservoir to 70 °C. Such a temperature is close to the critical temperature of oil boiling point (81 °C), which is undesirable and indicates the inevitability of reservoir pressure increase. At the pressure of 10 MPa, the minimum cost-effective oil flow rate (3.5–4.5 m3 per day) can be achieved at the temperature of 40–50 °C.

The maximum projected oil flow rate of 15 m3 per day cannot be provided by any combination of reservoir temperature and pressure. At the pressure of 10 MPa and the temperature of 80 °C, the maximum forecast flow rate is only 10 m3 per day, which proves the necessity of implementation of both thermal methods and reservoir permeability increasing methods (hydraulic fracturing—HF, acid HF, hydrochloric acid processing—HAT).

The optimum operating conditions for the deposit of reservoir A4, provided the application of thermal stimulation methods, could be the reservoir temperature of 50–60 °C and the pressure of 10 MPa. In this case, the oil flow rate will make up to 4.5–6 m3 per day. The preference of thermal methods is also supported by the relatively small, less than 1500 m, reservoir depth. To improve the cost-efficiency of the deposit development, the project provides the use of HF, acid HF and HAT, as well as chemical processing of well bottom hole zones in order to reduce the oil viscosity.

The values of critical pressure ΔP n and ΔP m are projected to be about 5 and 6 MPa, respectively. It is predicted that the original oil structure will be completely destroyed if the distance between the borehole bottoms is within 300 m over the entire developed area. At the distance ranging from 300 to 700 m, the drained area is expected to break into locations where oil will be flowed with completely and partially destroyed structure. The recommended variant of development provides the distance of 250–500 m between the wells; it eliminates the manifestation of structural and mechanical properties of oil under the pressure of 6.0–7.0 MPa.

The following facts are general and crucial for all projected objects. If the production wells in the simulation are placed on the structure so that each of them is in the transition flow zone of the adjacent well (see Fig. 4), the actual pressure gradient for the entire deposit will exceed the first critical pressure gradient of the oil. It is the formal basis for the use of linear Darcy law, and the average effective value of the oil viscosity, as the account in the hydrodynamic model of the parameters calculated by Eq. (5), allows minimizing the influence of structural and mechanical properties of oil on the process of its production.

Object 3

Permeability of the reservoir B1 was specified according to the results of field well testing using the pairs of values “flow rate—pressure” before putting the object into operation out of conservation.

Many carbonate collectors are characterized by a kind of conflict in which the permeability calculated according to the hydrodynamic well tests data is significantly higher than defined by the laboratory methods.

During the tests, anhydrous oil flow rate of 18.7 m3 per day was obtained at the pressure of 5.7 MPa. The reservoir pressure was 15.4 MPa; the bottom hole pressure in the studied well was 9.7 MPa. Multivariant calculations found that by altering within the permissible extent the size of the flow area and oil viscosity, it is impossible to obtain the identity of the left and right sides of Eq. (5). It has been suggested that the core permeability used in the calculation (0.045 µm2) is significantly underestimated. For this value of permeability, the calculated critical pressure gradients equalled: H r = 0.0819 MPa/m and H m = 0.1119 MPa/m.

The value of permeability for the area of reservoir B1 in the area of the tested well, specified according to the model (5), was 0.450 µm2. The rheological parameters have been adjusted, respectively: H r = 0.0226 MPa/m; H m = 0.0312 MPa/m.

Information obtained during the field well inflow testing and interpreted according to the model (5) served as the basis for quantitative revaluation of permeability differentiated in the deposit volume.

When building a flow model of a high-viscosity oil field, it is feasible to set initially a three-dimensional distribution of the first critical pressure gradient H r . The procedure itself is relatively simple and is implemented in several steps, as shown in Fig. 5. For the calculation, the specialist can use the data from laboratory experiments or correlation dependences allowing to calculate the values of rheological parameters, if one knows the oil and gas component analysis, temperature T and reservoir permeability k.

The resulting three-dimensional image is unique for each development variant, as it reflects the reaction of oil rheological parameters to the projected change in the thermobaric reservoir conditions and collector properties of the rocks. This allows recommending the variant that excludes the influence of structural and mechanical oil properties on the production.

Conclusions

The model of non-Newtonian flow in the form of the modified equation of the non-linear viscoplastic oil flow to the well is recommended as an intellectual application for the well-known hydrodynamic simulations. When calculating variants with vertical wells, it can help justify well spacing, the feasibility of address increase in the pressure drawdown and the use of thermal methods in order to achieve cost-effective flow rates.

The proposed method of hydrodynamic simulation taking into account non-Newtonian properties of high-viscosity oil and interpretation of field study results using hydrodynamic simulations of non-linear viscoplastic oil flow to the vertical well make it possible to characterize in terms of quantity the processes of structure formation with the most efficient use of the layer energy. This method has been implemented in our paper (Astafev et al. 2016) for the modelling process of intensification of high-viscosity oil with dual-well system.

Using an unconventional approach to the processing of indicator diagrams and hydrodynamic testing data for the developed wells, one can quickly specify the flow parameters of the collecting rock and diagnose the changes in reservoir oil viscosity.

Taking into account, the high-viscosity oil flow properties in the design contribute to the choice of reservoir stimulation system, which allows effective regulation of the structural and mechanical properties of oil and provides a high degree of field development.

References

Astaf’ev VI, Roters PV (2014) Simulation of oil recovery using the Weierstrass elliptic functions. Int J Mech 8:359–370

Astafev VI, Olkhovskaya VA, Gubanov SI (2016) Warm-up of layer in well with dual-well system and intensification of high-viscosity oil production. Oil Ind 2:66–69

Basniev KS, Dmitriev NM, Chilingar GV (2012) Filtration of non-Newtonian liquid. In: Mechanics of fluid flow, chap. 25. Wiley, New York, pp 489–512. doi:10.1002/9781118533628.ch25

Bernadiner MG, Entov VM (1975) Hydrodynamic theory of anomalous fluid flow through porous media. Nauka, Moscow (in Russian)

Bingham EC (1922) Fluidity and plasticity. McGraw-Hill, New York

Bird RB, Dai GC, Yarusso BJ (1983) The rheology and flow of viscoplastic materials. Rev Chem Eng 1:1–70

Bird RB, Armstrong RC, Hassager O (1987) Dynamic of polymeric liquids—vol 1: fluid mechanics, 2nd edn. Wiley, New York

Carreau PJ, DeKee DCR, Chhabra RP (1997) Rheology of polymeric systems: principles and applications. Hanser Publications, Munich

Casson N (1959) Flow equation for pigment oil suspensions of the printing ink type. In: Mill CC (ed) Rheology of disperse systems. Pergamon Press, New York, pp 84–104

Chhabra PR, Richardson JF (2008) Non-Newtonian flow and applied rheology: engineering applications, 2nd edn. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford

Chhabra RP, Comiti J, Machac I (2001) Flow of non-Newtonian fluids in fixed and fluidised beds. Chem Eng Sci 56:1–27

Dake LP (2001) The practice of reservoir engineering (revised edition). Shell Internationale Petroleum Maatschappij BV, The Hague

Devlikamov VV, Habibullin ZA, Kabirov MM (1975) Abnormal oil. Nedra Publishers, Moscow (in Russian)

Dietz DN (1965) Determination of average reservoir pressure from build-up surveys. J Petrol Technol 17(8):955–959

Gafarov SA, Shamaev GA (2005) A study of filtering parameters of non-Newtonian oil in the flow in carbonate porous media. Oil and Gas Business. http://www.ogbus.ru/authors/Gafarov/Gafarov_3.pdf (in Russian)

Herschel WH, Bulkley R (1926) Konsistenzmessungen von Gummi-Benzollosungen. Kolloid Zeitschrift 39:291–300

Khasanov MM, Bulgakova GT (2003) Nonlinear and nonequilibrium effects in the rheologically complex media. Institute of Computer Science, Moscow-Izhevsk (in Russian)

Mirzadzhanzade AKh, Khasanov MM, Bakhtizin RN (2005) Modelling of oil and gas production processes. Non-linearity, non-equilibrium, uncertainty. Institute of Computer Science, Moscow-Izhevsk (in Russian)

Mitsoulis E (2007) Flow of viscoplastic materials: models and computations. Rheol Rev 135–178

Olkhovskaya VA (2011) Underground hydromechanics. Non-Newtonian oil filtration. VNIIOENG, Moscow (in Russian)

Revizskiy YuV, Dyblenko VP (2002) Research and justification of the mechanism of oil reservoir recovery using physical methods. Nedra Publishers, Moscow (in Russian)

Syunyaev ZI, Safieva RZ, Syunyaev RZ (1990) Oil dispersion systems. Khimiya, Moscow (in Russian)

Wilkinson WL (1960) Non-Newtonian fluids: fluid mechanics, mixing and heat transfer. Pergamon Press, London

Zaydelson MI, Surovikov DJ, Vaynbaum SY et al (1991) Oil and gas potential of the Domanikoid associations of the Volga-Ural province. Int Geol Rev 33(3):243–262. doi:10.1080/00206819109465690

Acknowledgments

Research was carried out on the Grant of the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 15-17-00019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Astafev, V., Markelova, A., Olkhovskaya, V. et al. Modelling of non-linear viscoplastic oil flow to a well and development system selection. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 7, 521–529 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-016-0274-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-016-0274-2