Abstract

Drilling fluid losses into fractured shales is a major challenge. Lost circulation treatments are widely applied to mitigate the losses; however, the effectiveness of these treatments is affected by different physical properties of the used lost circulation materials (LCM). This paper presents an experimental investigation to study the effect of LCM type, concentration, particle size distribution, temperature, and LCM shape on the formed seal integrity, with respect to differential pressure, at different fracture widths. The overall objective of this study is to address the effectiveness of LCM treatments in sealing fractured shales, with specific application to the over consolidated Barents Sea overburden. Three commonly used LCMs that vary in size were used to formulate and evaluate the effectiveness of nine LCM blends. Nutshell blends effectively sealed different fracture widths with high seal integrities. Examination of the formed seal under an optical microscope and a scanning electron microscope revealed that this performance is due to the irregular shapes of these materials as well as their ability to deform under elevated pressure. Based on the results, it has been found that to effectively seal fractures using granular LCM treatments, the D90 value should be equal or slightly larger than the anticipated fracture width. However, due to both the increased risk of plugging downhole tools and the availability of larger LCM, granular LCM treatments can only be used to seal fractures up to 2000 microns. With the current limitations, other unconventional treatments are required to seal fractures wider than 2000 microns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Drilling in the Barents Sea has presented numerous operational problems due to fluid losses into pre-existing fractures. The Barents Sea is a complex geological area with several basins and platforms, which has sedimentary depositions from the Carboniferous (300+ million years) up to Tertiary periods. During the Cretaceous period, the area experienced compression with reverse faulting and folding, combined with extensional faults in some areas (Gabrielsen and Kloevjan 1997). The most significant exploration problem in the Barents Sea is related to the severe uplift and erosion in the range of 500–2000 m that took place during the Tertiary period (Dore 1995). Residual oil columns found beneath gas fields in the Hammerfest Basin indicate that the structures were once filled, or partially filled, with oil. The removal of up to 2 km of sedimentary overburden from the area, comparatively late in geological time, had severe consequences for these accumulations. Interestingly, the same complex geological history that created the fractures, which caused the cap rock to lose its integrity, also created severe loss problems in these shales.

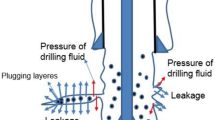

Pre-existing fractures have been identified in these formations in core studies (Gabrielsen and Kloevjan 1997). However, in their studies no detailed characterization of fractures widths was shown. For pre-existing fractures, it is important to distinguish between mechanically open and closed or hydraulically open and closed fractures as defined by Gutierrez et al. 2000. The formation can be brittle such that existing fractures can stay hydraulically open even if there are normal forces acting above the fracture plane (Nygaard et al. 2006). When fractures are hydraulically open, losses may occur if the mud weight is higher than the pore pressure gradient. Mitigating drilling fluid losses into existing fractures in overburden shale is a challenging problem due to the lack of available data of fracture widths in the area.

Treating the drilling fluid with conventional LCM as background treatments or concentrated pills is a common industry practice to mitigate seepage or partial losses. Other solutions that require more time for preparation and placement are used when severe losses are encountered such as cement (Messenger and McNiel 1952; Messenger 1981; Morita et al. 1990; Fidan et al. 2004), chemically activated cross-linked pills (CACP) (Bruton et al. 2001; Caughron et al. 2002), cross-linked cement (Mata and Veiga 2004), deformable-viscous-cohesive systems (DVC) (Whitfill and Wang 2005; Wang et al. 2005, 2008), nanocomposite gel (Lecolier et al. 2005), gunk squeezes (Bruton et al. 2001; Collins et al. 2010), and concentrated sand slurries (Saasen et al. 2004, 2011).

Different testing methods are used to evaluate the performance of LCM treatments, based on the fluid loss volume at a constant pressure, such as the particle plugging apparatus (PPA) or the high-pressure-high-temperature (HPHT) fluid loss in conjunction with slotted/tapered discs or ceramic discs (Whitfill and Miller 2008; Kumar et al. 2011; Kumar and Savari 2011). Other testing equipment has been developed to evaluate the sealing efficiency of LCM treatments in sealing permeable/impermeable fractured formations (Hettema et al. 2007; Sanders et al. 2008; Van Oort et al. 2009; Kaageson-Loe et al. 2008). Both particle size distribution (PSD) and total LCM concentration were found to have a significant effect on the sealing efficiency. It was also concluded that the fluid loss volume is not a good parameter to measure the sealing efficiency of LCM treatments.

The ability of particles to block a flow channel is a phenomenon not only relevant for the petroleum industry. Well known is the so-called Enstad theory for arching in hoppers and silos (Enstad 1975). This theory describes arching of dry powders where blockage can be formed even though the powder size is several order of magnitudes less than the hopper size. If the transporting medium for the powder is changed from a gas to a liquid, the liquid will wet the particles and lubricate the particle–particle and particle–wall contacts, leading to a completely different physical condition, which is much more difficult to handle mathematically. Therefore, it is expected that the function of LCM will depend on the particle morphology, the particle size distribution, the fluid the LCM is embedded into and the particle concentration.

In this study, experimental investigation of granular LCMs in terms of their seal integrity was carried out using pumpable LCM sizes in order to push the envelope of using LCM in sealing wide fractures thus cutting the time required to mitigate losses. The effect of LCM type, concentration, particle size distribution (PSD), temperature, and LCM shape on the formed seal integrity was investigated. The overall objective of this study is to address the effectiveness of LCM treatments in sealing fractured shales, with specific application to the Barents Sea overburden.

LCM treatments formulation

Three commonly used granular LCMs having different physical properties, including graphite (G), sized calcium carbonate (SCC), and nutshells (NS), were used in this investigation to formulate LCM treatments at different concentrations. To represent background treatments, a total concentration of 15 ppb (43 kg/m3) was used to formulate single LCM blends. For single LCM concentrated pills, a total concentration of 50 ppb (143 kg/m3) was used. In addition, two recommended LCM mixtures from previous studies (Aston et al. 2004; Hettema et al. 2007) were used in this study. Graphite and sized calcium carbonate blends (G & SCC) were investigated at two different concentrations, 30 ppb (86 kg/m3) and 80 ppb (228 kg/m3) to follow the recommendations by Aston et al. (2004). Graphite and nutshells blends (G & NS) were tested at the concentrations of 20 ppb (57 kg/m3) and 40 ppb (114 kg/m3) as suggested by Hettema et al. (2007). Unweighted water-based mud (WBM) containing 7 % bentonite was used to eliminate negative or positive effects, if any, of drilling fluid additives such as weighting materials and fluid loss reducers on LCM performance. 32 different granular LCM treatments were screened previously (Alsaba et al. 2014) at low pressure (100 psi) using four tapered discs, which represents mm sized fractures observed in shale core images from the Barents Sea (Norwegian Petroleum Directorate 2015), and a straight slotted disc with the specification shown in Table 1. The main objective of the screening phase was to investigate whether the tested blends were capable of sealing a specific fracture width and determines the fluid loss volume prior to sealing the fracture. From the results of 160 low-pressure tests (Alsaba et al. 2014), only nine granular LCM blends were selected for further evaluation at high pressure based on the measured fluid loss volume (Table 2).

The formulations of the selected blends are tabulated in Table 3 as a percentage of the total concentration of each LCM grade (Coarse to very fine).

Experimental methodology

High pressure LCM testing

The effectiveness of LCM treatments was investigated using a high-pressure LCM testing apparatus, which was designed and manufactured to evaluate the formed seal integrity. The seal integrity is defined here as the maximum pressure at which the formed seal breaks and fluid loss resumes. A schematic diagram of the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1. A plastic accumulator (1) used to transfer the drilling fluids to the metal accumulator (2) prior to pressurizing the fluids containing LCM treatments inside the testing cell (3) through the tapered discs (4) using Isco™ pump (DX100) (5), which is connected to a computer (6) for pressure versus time measurements, at a flow rate of 25 ml/min. The testing cell can be heated up to 300 °F (149 °C) using an insulated heating blanket. This heating blanket was used in measurements with the scope to investigate the effect of temperature by repeating some tests at a higher temperature of 180 °F (82 °C). This temperature is a relevant temperature for field operations and was found to represent the average temperature in overburden shale (Haider 2013). The results from the high temperature tests were compared with the results obtained at room temperature.

Forcing the fluids through the tapered discs will result in an increase in the injection pressure, which indicates the seal formation within the fracture. Fluid injection continues until reaching the highest pressure (seal integrity) followed by a significant pressure drop with no pressure buildup afterward, which indicates breaking the formed seal.

Particle size distribution analysis

To study how PSD correlates with the seal integrity, dry sieve analysis tests were conducted. Samples of LCM treatment were sieved through a series of stacked sieves. The cumulative weight percent retained for each sieve size was calculated from the measured weight retained in each sieve and then plotted versus the sieve sizes. The main five parameters, which were obtained from the resulting plot, are the D10, D25, D50, D75, and D90, measured in microns, for the different blends. The D value indicates the size where the percent of the particles are less than the D number.

Optical and scanning electron microscope

To correlate the performance of LCM with the particles morphology data like sphericity and roundness, a qualitative visual inspection of LCM particles was carried out by using the sphericity and roundness chart suggested by Powers (1953). LCM particles and the formed seals were examined under an optical microscope and a scanning electron microscope (SEM). The inspected formed seals were gently removed from the tapered discs after running the test and left to dry prior to inspection.

Results and discussion

The measured seal integrities at room temperature for the LCM treatments using the high-pressure LCM testing apparatus are presented in Table 4 in addition to four tests, which were conducted at higher temperature (180 °F). Three tests were also repeated at the same conditions to test result repeatability. All LCM treatments failed to establish a seal within the 3000 microns straight slotted disc (SS1) under low pressure; as a result they were excluded from the high pressure testing matrix. Our findings in the screening phase are in agreement with the previous investigation conducted by (Nayberg 1987), where none of the conventional LCMs were able to seal a 3300-micron slot when subjected to 1000 psi (6.89 MPa).

Table 5 shows the particle size distribution analysis (PSD) for the used 9 blends, which was analyzed using the dry sieve analysis techniques.

Effect of LCM type and fracture width

To investigate the effect each parameter has on the seal integrity, the seal integrities were plotted with respect to one variable at a time. Four colors are used to define the tapered disc as follows: blue for TS1, red for TS2, orange for TS3, and purple for TS4 (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6).

From the plotted results of the three high concentrations (50 ppb) single LCM treatments shown in Fig. 2a, nutshells resulted in higher seal integrities at the two fracture widths (up to 2200 psi) compared to graphite (449 psi) and sized calcium carbonate (589 psi). The same was observed for LCM mixtures shown in Fig. 2b, where treatments containing nutshells and graphite (40 ppb) exhibited higher sealing integrities up to 2800 psi compared to the other blend containing graphite and sized calcium carbonate at higher concentration (80 ppb) for the two different fracture width (589 and 224 psi for TS1 and TS2, respectively). In general, as anticipated, increasing the fracture width resulted in weaker seal integrities.

Effect of concentration

Figure 3 shows the effect of increasing the LCM concentration on the seal integrities at the different fracture width for both single LCM and mixtures. By increasing the concentration of nutshells from 15 to 50 ppb the seal integrities improved approximately 500 % (Fig. 3a). For graphite and nutshells blend (Fig. 3b), the seal integrities were improved when tested using TS1 and TS2 by 22 and 113 %, respectively.

Effect of particle size distribution

To correlate the PSD with variation in the seal integrities, the seal integrities for each fracture width are plotted on the left y-axis versus the particle size distribution obtained from the dry sieve analysis on the right y-axis as shown in Figs. 4 and 5. It is clearly observed that the D90 plays the most significant effect on the overall seal integrities where larger particle sizes resulted in enhancing the seal integrities. In other words, the D90 value should be selected such that it matches the fracture width to ensure fracture sealing, which is in agreement with previous findings (Smith et al. 1996; Hands et al. 1998). The improved performance of treatments containing nutshells is attributed to the fact that the D90 values of theses blends ranging between 1900 and 2400 microns are higher than the fracture widths (Figs. 4, 5). All LCM treatments having a D90 that is smaller than the used fracture width failed to establish a seal within the fracture. Based on the results, it is recommended that the D90 for any granular LCM treatment for a specific fracture width be equal or slightly larger than the expected fracture width.

Effect of temperature

Figure 6 shows a comparison between four tests, which were conducted at both room temperature and high temperature (HT) of 180 °F (82 °C). The seal integrity of graphite and calcium carbonate blend were not affected significantly by the high temperature, where a reduction from 584 to 537 psi (8 %) was observed. For both tests using graphite and nutshells treatments at 20 and 40 ppb, a reduction in the seal integrity was observed at 180 °F by 11 and 30.5 %, respectively. However, when a 50 ppb nutshell only was tested at higher temperature, an increase in the seal integrity from 755 to 1164 psi (54 %) was observed (Fig. 6).

The variation in the seal integrities of the different blends when tested at higher temperature suggests that temperature has a significant effect on LCM performance. The reduction in the seal integrity for graphite and nutshell blends could be attributed to the increased graphite lubricity at high temperature, since graphite is known for acting as a solid lubricant (Alleman et al. 1998; Savari et al. 2012).

The increase in the seal integrity for nutshells blend was experimentally confirmed to be due to the swelling of nutshell particles at higher temperature. A swelling test, using a linear swell meter following the design and procedure used to quantify the swelling of shale (Fann 2015), was conducted to investigate the effect of temperature on nutshells. The results showed a 3 % swelling (water soak) over 24 h at room temperature. However, at higher temperature (180 °F), nutshells exhibited approximately 13 % swelling as shown in Fig. 7. Based on these tests, temperature is another factor that could improve, or reduce, the seal integrity for some LCM treatments. Therefore, it is recommended to evaluate the seal integrity of LCM treatments at higher temperatures.

Effect of LCM shape

To link the performance of the different LCM treatments with the varying physical properties of LCMs, optical microscopy was first used to inspect sphericity and roundness of LCM particles (Fig. 8). From the images and by using the sphericity and roundness chart by Powers (1953), graphite particles (Fig. 8a, d) in general could be described as sub-rounded with high sphericity. Calcium carbonate particles can be classified as sub-angular with high sphericity (Fig. 8b, e). Nutshell particles (Fig. 8c, f) could be described as angular with low sphericity.

From hydraulic fracturing application, proppant with high sphericity and roundness will result in higher fracture conductivity (Cutler et al. 1985). However, the main objective of LCM treatment is to reduce the fracture conductivity by forming an impermeable seal within the fracture that prevents further fluid losses into the formation. Based on the qualitative analysis of LCM particles, the angularity and low sphericity of nutshells resulted in higher seal integrities (up to 2800 psi) due to the low permeability of the formed seal. On the contrary, the high sphericity of both graphite and calcium carbonate, resulted in relatively higher seal permeability and thus lower seal integrities.

In addition, it can be also observed that nutshell particles are poorly sorted (Fig. 8c), i.e. have wider variation in the particles’ sizes and shapes, which is in agreement with the PSD analysis shown in Table 4. This variation in nutshell particle sizes enhanced the sealing capabilities compared to graphite and calcium carbonate, which are moderately sorted.

Figure 9a–c show the formed seal of the different blends, which is believed to have formed as a result of the fracture tip being bridged with large LCM particles and then filled with more LCMs. In general, it observed that the finer particles helped in sealing the voids between other coarser particles. The low particles sphericity and angularity of nutshells improved the formation of a tighter seal (Fig. 9b), which translated into higher seal integrities for nutshell blends.

The formed seals were further inspected under SEM (Fig. 10). When analyzing SEM images, the dark spots represent void spaces between LCM particles. The formed seal of nutshells (Fig. 10a) shows that both the low sphericity of nutshells particles as well as the wide PSD (poor sorting) enhanced the seal integrity as the particles were aligned in a favorable way, which resulted in less void spaces within the formed seal. The formed seal using graphite and calcium carbonate blend is shown in Fig. 10b. This seal exhibited more void spaces than the nutshells’ seal as a result of the high sphericity of both graphite and calcium carbonate particles, which resulted in higher seal permeability and thus lower seal integrity. The different shapes of nutshells as well as the presence of the finer graphite particles (Fig. 10c) resulted in high seal integrity for graphite and nutshells blend compared to the other blends.

As observed from this investigation, granular LCM particle size plays a significant role in sealing anticipated fractures. However, the pumpability challenges associated with the increased risk of plugging downhole tools place a limitation on the maximum LCM particle size that can be used in LCM treatments. As a result, other unconventional treatments that are able to be pumped through downhole tools without plugging them are required to seal wider fractures.

Conclusions and recommendations

-

Conventional LCMs used in this study were able to seal fractures up to 2000 microns. For fractures wider than 2000 microns, other unconventional treatments are required.

-

The risk of plugging downhole tools as well as the availability of larger LCMs places an upper limit on the maximum particle size that can be used in granular LCM treatments.

-

The variation in the sealing integrities under high temperatures suggests that LCM treatments should be evaluated at the expected formation temperature.

-

The increase in the seal integrity for nutshells when used in single LCM treatment at high temperature is attributed to the swelling of nutshell particles, which was quantified experimentally.

-

LCM particle shape, in terms of sphericity and roundness, showed a significant effect on the overall seal integrities.

-

Based on both optical microscopy and SEM images, the low sphericity and angularity of nutshell particles resulted in maintaining higher seal integrities compared to graphite and calcium carbonate.

-

The SEM images showed that the irregular shapes of nutshells resulted in a better alignment of the particles within the fracture, which explains the improved performance of nutshell treatments.

-

PSD showed a significant effect on the seal integrities, especially the D90 value, where a D90 value that is equal or slightly larger than the fracture width was required to initiate a strong seal. The presence of very fine particles in LCM treatments is recommended to fill the void spaces between other coarser particles, which in turn will result in a less permeable seal and higher seal integrity.

-

The experimental investigation showed comparable trends where the seal integrities increased by increasing LCM concentration, which is in agreement with previous investigations.

-

Blends containing nutshells showed the best performance in terms of sealing fractures at both low and high concentrations.

References

Alleman J, Owen B, Cornay F, Weintritt D (1998) Multi-functional solid lubricant reduces friction/prevents mud loss. World Oil 219:87–90

Alsaba M, Nygaard R, Saasen A, Nes O (2014) Lost circulation materials capability of sealing wide fractures. In: SPE deepwater drilling and completions conference, Galveston, USA, 10–11 September. doi:10.2118/170285-MS

Aston M, Alberty M, McLean M et al (2004) Drilling fluids for wellbore strengthening. In: IADC/SPE Drilling Conference, Dallas, Texas, 2–4 March. doi:10.2118/87130-MS

Bruton J, Ivan C, Heinz T (2001) Lost circulation control: evolving techniques and strategies to reduce downhole mud losses. In: SPE/IADC drilling conference, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 27 February–1 March. doi:10.2118/67735-MS

Caughron D, Renfrow D, Bruton J et al (2002) unique crosslinking pill in tandem with fracture prediction model cures circulation losses in deepwater Gulf of Mexico. In: IADC/SPE drilling conference, dallas, Texas, USA, 26–28 February. doi:10.2118/74518-MS

Collins N, Whitfill D, Kharitonov A, Miller M (2010) Comprehensive approach to severe loss circulation problems in Russia. In: SPE Russian oil and gas conference and exhibition, Moscow, Russia, 26–28 October. doi:10.2118/135704-MS

Cutler R, Enniss D, Jones A, Swanson S (1985) Fracture conductivity comparison of ceramic proppants. SPE J 25:157–170. doi:10.2118/11634-PA

Dore AG (1995) Barents Sea geology, petroleum resources and commercial potential. Arctic 48:207–221

Enstad G (1975) On the theory of arching in mass hoppers. Chem Eng Sci 30:1273–1283

Fann Instrument Company (2015) Linear Swell Meter 2100 instruction manual. http://www.fann.com/public1/pubsdata/Manuals/LSM_2100_Manual_102114531.pdf. Accessed 31 July 2015

Fidan E, Babadagli T, Kuru E (2004) Use of cement as lost-circulation material: best practices. In: Canadian international petroleum conference, Calgary, Alberta, 8–10 June. doi:10.2118/2004-090

Gabrielsen H, Kloevjan O (1997) Late Jurassic-early Cretaceous caprocks of the southwestern Barents Sea: fracture systems and rock mechanical properties. In: Hydrocarbon seals: importance for exploration and production. NPF Special Publication, vol 7, pp 73–89. Elsevier, Singapore

Gutierrez M, Øino L, Nygaard R (2000) Stress-dependent permeability of a de-mineralised fracture in shale. Mar Petrol Geol 17:895–907. doi:10.1016/S0264-8172(00)00027-1

Haider S (2013) Imaging reservoir quality: seismic signature of geological processes, SW Loppa High, Norwegian Barents Sea. Thesis, University of Oslo

Hands N, Kowbel K, Maikranz S, Nouris R (1998) Drill-in fluid reduces formation damage, increases production rates. Oil Gas J 96:65–69

Hettema M, Horsrud P, Taugbol K et al (2007) Development of an innovative high-pressure testing device for the evaluation of drilling fluid systems and drilling fluid additives within fractured permeable zones. In: Offshore mediterranean conference and exhibition, Ravenna, Italy, 28–30 March. OMC-2007-082

Kaageson-Loe N, Sanders M, Growcock F, Taugbol K, Horsrud P, Singelstad A, Omland T (2008) Particulate-Based Loss-Prevention Material--The Secrets of Fracture Sealing Revealed!. IADC/SPE Drilling Conference, Orlando, Florida, USA, 4–6 March 2008. doi:10.2118/112595-MS

Kumar A, Savari S (2011) Lost circulation control and wellbore strengthening: looking beyond particle size distribution. In: AADE national technical conference and exhibition, Houston, Texas, USA, 12–14 April. AADE-11 NTCE-21

Kumar A, Savari S, Jamison D et al (2011) Application of fiber laden pill for controlling lost circulation in natural fractures. In: AADE national technical conference and exhibition, Houston, Texas, USA, 12–14 April. AADE-11 NTCE-19

Lecolier E, Herzhaft B, Rousseau L et al (2005) Development of a nanocomposite gel for lost circulation treatment. In: SPE european formation damage conference, Sheveningen, The Netherlands, 25–27 May. doi:10.2118/94686-MS

Mata F, Veiga M (2004) Crosslinked cements solve lost circulation problems. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, Houston, Texas, USA, 26–29 September. doi:10.2118/90496-MS

Messenger J (1981) Lost circulation. PennWell Corp, Tulsa

Messenger J, McNiel J (1952) Lost circulation corrective: time-setting clay cement. J Pet Technol 4:59–64. doi:10.2118/148-G

Morita N, Black A, Fuh G-F (1990) Theory of lost circulation pressure. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 23–26 September. doi:10.2118/20409-MS

Nayberg T (1987) Laboratory study of lost circulation materials for use in both oil-base and water-base drilling muds. SPE Drill Eng 2:229–236. doi:10.2118/14723-PA

Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (2015) Fact pages. http://factpages.npd.no/factpages/. Accessed 12 November 2015

Nygaard R, Gutierrez M, Bratli R (2006) Brittle-ductile transition, shear failure and leakage in shales and mudrocks. Mar Petrol Geol 23:201–212. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2005.10.001

Powers MC (1953) A new roundness scale for sedimentary particles. J Sediment Petrol 23:117–119

Saasen A, Godøy R., Breivik D et al (2004) Concentrated solid suspension as an alternative to cements for temporary abandonment applications in oil wells. In: SPE technical symposium of Saudi Arabia section, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, 15–17 May. SPE-SA-34

Saasen A, Wold S, Ribesen B et al (2011) Permanent abandonment of a North Sea Well using unconsolidated well plugging material. SPE Drill Complet 26:371–375. doi:10.2118/133446-PA

Sanders M, Young S, Friedheim J (2008) Development and testing of novel additives for improved wellbore stability and reduced losses. In: AADE fluids conference and exhibition, Houston, USA, 8–9 April. AADE-08-DF-HO-19

Savari S, Whitfill D, Kumar A (2012) Resilient lost circulation (LCM): a significant factor in effective wellbore strengthening. In: SPE deepwater drilling and completions conference, Galveston, Texas, USA, 20–21 June. doi:10.2118/153154-MS

Smith P, Browne S, Heinz T, Wise W (1996) Drilling fluid design to prevent formation damage in high permeability quartz arenite sandstones. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, Denver, Colorado, 6–9 October. doi:10.2118/36430-MS

Van Oort E, Friedheim J, Pierce T, Lee J (2009) Avoiding losses in depleted and weak zones by constantly strengthening wellbores. SPE Drill Complet 26:519–530. doi:10.2118/125093-PA

Wang, H, Sweatman R, Engelman R et al (2005) The key to successfully applying today’s lost circulation solutions. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, Dallas, Texas, USA, 9–12 October. doi:10.2118/95895-MS

Wang H, Sweatman R, Engelman R et al (2008) Best practice in understanding and managing lost circulation challenges. SPE Drill Complet 23:168–175. doi:10.2118/95895-PA

Whitfill D, Miller M (2008) Developing and testing lost circulation materials. In: AADE fluids conference and exhibition, Houston, Texas, USA, 8–9 April. AADE-08-DF-HO-24

Whitfill D, Wang H (2005) Making economic decisions to mitigate lost circulation. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, Dallas, Texas, USA, 9–12 October. doi:10.2118/95561-MS

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Det Norske Oljeselskap ASA for the financial support under research agreement # 0037709; Jason Scorsone from Halliburton for his support; Dr. Wisner, Dr. Wronkiewicz, and Dr. Galecki from Missouri University of Science and Technology for their help with the microscope work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsaba, M., Nygaard, R., Saasen, A. et al. Experimental investigation of fracture width limitations of granular lost circulation treatments. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 6, 593–603 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-015-0225-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-015-0225-3