Abstract

The instability of a wellbore is still one of the common problems during drilling. The cause of such a borehole failure can often be mitigated by suitably determining the critical mud pressure as well as the best well trajectory. Therefore, we could save the time and the cost of drilling and production significantly by precluding some drilling problems. The main objective of this paper is to apply a geomechanical model based on well data including the in situ stresses, pore pressure, and rock mechanical properties coupled with suitable rock failure criteria in order to obtain a safe mud window and a safe drilling direction. The Mogi–Coulomb failure criterion was used for deriving the failure equations for tensile and compressive failure modes. For comparison, the analysis was also carried out using the traditional Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion. Variations of wellbore inclination and azimuth were also used to recommend upper and lower mud pressure bounds and the most stable borehole orientations. The best trajectory selection for the inclined borehole was also investigated. Furthermore, the effect of drilling mud pressure and wellbore orientation (θ = 0o) and (θ = 90o) on wellbore stability and stress distribution around the wellbore was assessed. The stability model has been applied to a well located in an oilfield in Iran and showed that the new model is consistent with field experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Wellbore instability is one of the main problems that engineers encounter during drilling. Borehole stability requires the knowledge of interaction between rock strength and in situ stress. The drilling of an in-gauge hole is an interplay of two factors: uncontrollable and controllable. Uncontrollable factors are the earth stresses (horizontal and vertical), pore pressure, rock strength and rock chemistry. Controllable factors include mud weight, wellbore azimuth and inclination (Mohiuddin and Khan 2007). Therefore, the way to prevent wellbore instability during drilling is to adjust engineering practices by choosing optimal wellbore trajectories and mud weights. From the mechanical perspective, a wellbore can fail by induced stresses (usually two types): shear failure and tensile failure, which can lead to a stuck pipe, wellbore breakout, induced fracture, poor cementation, side track, and loss of drilling mud (Mclean and Addis 1994). Therefore, critical mud pressure should be considered in order to mitigate wellbore instability-related problems. Although, the selection of a suitable failure criterion for wellbore stability analysis is difficult and controversial (Al-Ajmi and Zimmerman 2009), numerous drilling engineers tried to predict wellbore stability prior to drilling, via different rock failure criteria, and they also investigated stress concentration around the wellbore in order to propose an optimum mud weight window for a successful drilling operation.

Awal et al. (2001) indicated that the optimal well path can be vertical, deviated, or horizontal, depending on stress regimes. Al-Ajmi and Zimmerman (2009) used the Mogi–Coulomb criterion to develop a model for wellbore stability analysis and indicated that the Mogi–Coulomb criterion shows field conditions more realistically. Zhang et al. (2010) evaluated five rock failure criteria, namely, the Mohr–Coulomb, Drucker–Prager, modified Lade, Mogi–Coulomb and three-dimensional (3D) Hoek–Brown criteria and found that 3D Hoek–Brown and Mogi–Coulomb criteria are suitable for wellbore stability analysis.

In the present study we first review and define the Mohr–Coulomb and Mogi–Coulomb criteria. We then use Mogi–Coulomb failure criterion for predicting wellbore stability and determining of mud weight window and stress distribution around the wellbore wall. For comparison, the analysis is also carried out using the traditional Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion. Then both criteria were applied to a well located in an oilfield in Iran.

A series of sensitivity analyses that demonstrate the influences of drilling mud pressure and borehole orientation on wellbore stability are then presented and discussed.

Rock strength criteria

Mohr–Coulomb criterion

The Mohr–Coulomb shear-failure model is one of the most widely used models for evaluating borehole collapse due to its simplicity (Horsrud 2001; Fjaer et al. 2008). The Mohr–Coulomb criterion can be expressed based on shear stress and the effective normal stress as given below.

where τ is the shear stress, σ n is the normal stress, c and ϕ are the cohesion and the internal friction angle of the rock, respectively.

The Mohr–Coulomb criterion uses unconfined compressive strength (UCS) and angle of internal friction (ϕ) to assess the failure (Khan et al. 2012), and then it can be expressed in terms of the maximum and minimum principal stresses, σ 1 and σ 3.

where q is a parameter related to ϕ and σ c is the unconfined compressive strength of the rock. The parameters q and σ c can be determined, respectively, by (Zhang et al. 2010).

This criterion can also be rewritten as follows:

Considering the Mohr–Coulomb criterion, shear failure occurs if F ≤ 0, and accordingly, the required mud weight to prevent failure in each mode of failure can be calculated.

Mogi–Coulomb criterion

Like Mohr–Coulomb criterion, the Mogi–Coulomb criterion describes the shear failure mechanism using a linear relationship of shear stress and normal stress. The Mogi–Coulomb criterion was proposed by Al-Ajmi and Zimmerman (2005) and is simply written as:

where σ m,2 and τ oct are the mean stress and the octahedral shear stress, respectively, that are defined by:

And a and b are material constants which are simply related to c and ϕ as follows:

This criterion can also be rewritten as follows:

Considering the Mogi–Coulomb criterion, shear failure occurs if F ≤ 0.

Determination of stress orientation in deviated wells

Far-field stresses in a coordinate system referred to the borehole:

where σ v, σ H and σ h are the vertical, maximum and minimum horizontal stresses, respectively, the angle α corresponds to the deviation of the borehole from σ H, and the angle, i, represents the deviation of the borehole from σ v (Aminul et al. 2009).

The total stress distribution around the wellbore is given in cylindrical coordinate system (r, z, θ) and are given by the Fig. 1 below.

When analyzing stress and pore pressure distributions in and around wellbores the polar coordinate system is generally adopted. For the generalized plane, strain formulation the stresses in polar coordinates are related to the Cartesian coordinate stresses according to the following rules:

where σ rr, σ θθ , σ zz are the radial, tangential, and axial stresses, respectively, and ν is a material constant called Poisson’s ratio. The angle θ is measured clockwise from the x-axis, as shown in Fig. 1 (Zhang et al. 2003).

The principal stresses at any given location on the borehole wall in which shear stress is zero are given by the following equation:

where σ tmax is the largest and σ tmin is the smallest principal stress. Radial stress is the other principal stress (Zoback 2007).

When the maximum principal stress exceeds the effective strength, failure takes place at that location. Eventually, the calculated principal stresses can be used in rock failure criteria in order to assess wellbore stability.

Wellbore failure mechanisms

Drilling a well in a formation changes the initial stress state and causes stress redistribution in the vicinity of the wellbore. The redistributed stress state may exceed the rock strength and hence, failure can occur. Generally, a wellbore fails either by exceeding the tensile strength of the formation or by exceeding the shear strength of the formation (Chen 1996). These two types of failures are explained in detail below.

Compressive shear failure

Shear failure usually results in borehole collapse or breakout. Borehole breakouts are collapsed regions located on the least horizontal principal stress for vertical wells and are generally formed by compressive shear failure. Therefore, compressional failure will occur in the direction of the minimum horizontal stress because the tangential stress will reach a maximum here.

Tensile failure

In general, the borehole tensile failure is defined by the minimum principal stress. Therefore, this failure becomes the upper limit of the mud weight window in safe drilling operation. Fracture initiates when the minimum effective stress (i.e., the total stresses minus the formation pore pressure) at the wellbore wall reaches or exceeds formation rock tensile strength, T (Fjaer et al. 2008). Thus, failure occurs when σ 3 − P o ≥ − T.

The proposed methodology can be applied by following algorithm and the results obtained from this solution are shear failure and tensile failure determination in order to calculate the optimum mud window.

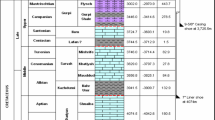

In this section, we will apply the Mohr–Coulomb and Mogi–Coulomb criteria to analyze the wellbore instability problems. The case study is conducted on a carbonate formation and the offset well data used in this paper are listed in Table 1. The data needed for the study were derived from field measurements. The mechanical properties of the carbonate reservoir were obtained by conducting a number of unconfined compressive strength and triaxial tests on reservoir cores and were then correlated with the properties derived from open-hole logs. The magnitudes of the in situ stresses and formation pressure were derived from analysis of open-hole logs and leak-off test data.

The rock data are used to predict the safe mud-drilling window for drilling in the reservoir. Hole collapse and fracture pressures are calculated as functions of inclination, i, and azimuth, α, for all possible combinations, and potential wellbore instability issues can be determined. Matlab programming language is used to perform all the procedures in the different sections of the methodology (Fig. 2).

Mud weight window versus depth

It is known that there is a lower limit of mud weight below which compressive failure occurs, and an upper limit beyond which tensile failure occurs. The range between the lower and the upper limit is defined as the mud weight-window. The derived equations from the Mohr–Coulomb and the Mogi–Coulomb criteria accompanying rock mechanics and stress properties can be used to determine the optimum mud weight window. Figure 3 illustrates the safe mud window predicted by Mohr–Coulomb and Mogi–Coulomb criteria for three states of vertical, slanted, and horizontal wells in which the mud weight window expands gradually with increasing drilling depth. In vertical state, (Fig. 3a), at the depth of 3190 m, the optimum mud pressures predicted by Mohr–Coulomb and Mogi–Coulomb criteria are equal to 60.65 and 61.84 MPa; the maximum shear failure pressures are 40.03 and 72.73 MPa, and the minimum fracture pressures are 81.07 and 80.47 MPa, respectively. Since there is a little difference between maximum and minimum horizontal stresses, the safe mud windows obtained by these two criteria are nearly the same. Figure 3a–c depict that increasing well inclination causes narrowing the safe mud window which show vertical well is more stable than slanted and horizontal well. In the horizontal state, more attention should be paid for mud weight determination in order not to exceed fracture and shear failure gradients.

Mud weight window versus wellbore inclination and azimuth

All the aforementioned studies optimized the well trajectory based on the analysis of the effects of well inclination and azimuth on mud weight window. Figure 4 shows the safe mud weight window for wellbore stability in different inclinations obtained by the Mohr–Coulomb and the Mogi–Coulomb criteria. It shows that the mud weight window is narrowed gradually with the increase in wellbore inclination that represents a vertical well requires the lowest mud weight to prevent breakout and, conversely, horizontal wells require the highest mud weight to maintain wellbore stability. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, the fracture and shear failure pressure predicted by the Mohr–Coulomb criterion at the inclination of 0° are about 80.36 and 40.3, and at the inclination of 90° they are about 62.11 and 51.18 MPa, respectively, and the optimum mud pressure will be obtained within the range of the mud weight window. Figure 4b shows that at inclinations of 30, 60, and 90, the safe mud window obtained by Mogi–Coulomb criterion is a little wider than that determined by Mohr–Coulomb criterion since the rock strength predicted by Mogi–Coulomb is higher than that predicted by Mohr–Coulomb criterion. The fracture and the shear failure pressure predicted by the Mogi–Coulomb criterion at inclination of 0° are 80.14 and 41.17 MPa, and at the inclination of 90° they are about 63.85 and 46.68 MPa, respectively. Also, the magnitudes of fracture and the shear failure pressure at inclinations of 30 and 60° are shown in boxes.

To further illustrate the relationship between mud weight window and well azimuth, a mud weight window (Fig. 5) was generated at a given well inclination 30°. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, the minimum mud pressure at which fracture will occur is 68.51 MPa at azimuth of 0° and 180°. At azimuths of 90° and 270° the fracture pressure is about 77.38 MPa. The maximum mud pressure at which shear failure will occur is 43.81 MPa at azimuth of 0° and 180°. The least mud pressure window is found in both azimuths 0° and 180° and the highest mud pressure window is found in both azimuths 90° and 270°. Figure 5b shows the safe mud pressure window predicted by Mogi–Coulomb criterion that is a little wider than that predicted by Mohr–Coulomb criterion. At azimuth 0° and 180° the mud pressure window is similar and between 40.59 and 67.91 MPa. The largest mud weight window is located in azimuths 90° and 270° that is between 39.61 and 78.72 MP. This represent that for drilling the well with inclination 30°, drilling at azimuths 90° and 270° are the most stable states and conversely, drilling at azimuths 0° and 180° are the least stable states.

Effective stress distribution around the wellbore

In this part, the stress distribution around the wellbore based on change in mud pressure and well orientation, θ, is assessed. Figure 6 shows the effective radial, tangential and axial stresses as a function of radial position away from the borehole in which inclination, azimuth, and orientation are 30°, 67°, and 90° respectively. Both radial, σ r, and tangential, σ θ , stresses vary with distance from the borehole and approach the far-field stresses at a radial distance of r = 5R (where R is the borehole radius). As illustrated in Fig. 6a, b, radial and tangential stresses are proportional to mud pressure in which increasing mud pressure causes a decrease in the tangential stress and an increase in the radial stress. Since the tangential stresses are higher than the radial stresses in all the states, compressive failure will occur in this part of the well (θ = 90o). At all used mud pressures the axial stress is nearly constant and at radial distance of more than 1.4, it is maximum principal stress. The magnitude of stresses around the wellbore is shown in boxes.

It should be pointed out that the reason of applying inclination of 30° and azimuth of 67° for this study is understanding of effective stress distribution around the wellbore drilled in this study.

Figure 7 shows the effective radial, tangential and axial stresses as a function of radial position away from the borehole in which inclination, azimuth, and orientation are 30°, 67°, and 0°, respectively. As shown in Fig. 7a, the tangential stress is greater than the radial stress at the wellbore wall (r/a = 1) to a dimensionless radial distance of about 3.6. However, at the distance of more than 3.6 the radial stress is more than tangential stress indicating tensile failure may occur in those ranges. As depicted in Fig. 7a–d, by increasing mud pressure, the tangential and radial stresses cross each other at closer dimensionless radial distances which are shown in boxes.

From Figs. 6 and 7 can be concluded that the effect of mud pressure on stress distribution in the radial direction is affected by the orientation of the wellbore stresses. At θ = 90o the tangential stress reaches its highest value for a greater section of the radial distances from the wellbore. At θ = 0o the tangential stress reaches its lowest value and the axial or radial stresses may become maximum at the radial distances from the wellbore as mud weight increases.

Figure 8 shows the effective stress distribution around the wellbore based on the mud pressure. The orientation of wellbore is ranging from 0° to 360° and the dimensional radial distance is equal to 1, where r = a, and the radius of the wellbore is 3.1 in.

As illustrated in Fig. 8a and b, at mud pressure of 46 and 50 MPa the maximum tangential stress is at 80° 260°. Since the mud pressure is low the radial stress is the minimum principal stress and shear failure may occur. In Fig. 8c axial stress is the maximum principal stress and radial stress is minimum principal stress that at orientations of 0°, 170°, 350° it is nearly abutted with tangential stress indicating fracture initiation at theses orientations. The maximum magnitude of the tangential stress at which compressive failure will occur is 39.31 MPa.

Figure 8d shows that at mud pressure of 60 MPa the radial stress is greater than the tangential stress for the ranges 0°–20°, 130°–200°, and 310°–360° indicating that tensile failure may occur in those ranges. The tangential stress is greater than the radial stress between 20° and 130°, and also between 200° and 310° thus indicating that compressive failure may occur. The axial stress is the maximum principal stress at mud pressures of 57 and 60 MPa. Therefore, increase in the drilling mud pressure causes an increase in radial stress and a decrease in the tangential stress around the wellbore wall.

Conclusion

-

1.

We observed that the agreement between both Mohr–Coulomb and Mogi–Coulomb criteria is excellent. If maximum and minimum horizontal stresses are too close, the Mogi–Coulomb failure criterion results would be very close to the results from the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion.

-

2.

At a wellbore inclination of 30°, drilling at azimuths 90° and 270° are the most stable states and the highest safe mud weight window is found in these two azimuths. The least mud weight windows, which represent the least stable state, are found at azimuth 0 and 180°.

-

3.

Since the resultant stress difference between the minimum and maximum horizontal stresses is smaller than that between the overburden and horizontal stresses, vertical direction is the most stable well trajectory.

-

4.

At wellbore inclination of 30°and orientation of 80° and 260°, the tangential stress is maximum principle stress, however at orientation of 170° and 350°, the tangential stress is minimum and the radial and axial stresses are maximum depending on mud pressure.

-

5.

An increase in the hydrostatic mud pressure indicates an increase in the radial stress and a decrease in the tangential stress; they are also influenced by the wellbore orientation.

References

Al-Ajmi AM, Zimmerman RW (2005) Relation between the Mogi and the Coulomb failure criteria. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 42:431–439

Al-Ajmi AM, Zimmerman RW (2009) A new well path optimization model for increased mechanical borehole stability. J Petrol Sci Eng 69:53–62

Aminul I, Skalle P, Tantserev E (2009) Underbalanced drilling in shales-perspective of mechanical borehole instability. International Petroleum Technology Conference 13826

Awal MR, Khan MS, Mohiuddin MA, Abdulraheem A, Azeemuddin M (2001) A new approach to borehole trajectory optimization for increased hole stability. Paper SPE 68092 presented at the SPE Middle East Oil Show held in Bahrain

Chen X (1996) Wellbore stability analysis guidelines for practical well design. SPE 00036972:117–126

Fjaer E, Holt R, Horsrud P, Raaen A, Risnes R (2008) Petroleum related rock mechanics. 2nd Edition, Elsevier

Horsrud P (2001) Estimating mechanical properties of shale from empirical correlations. SPE 56017 Drilling and completion 16: 68-73

Khan S, Ansari S, Khosravi N (2012) Prudent and integrated approach to understanding wellbore stability in canadian foothills to minimize drilling challenges and non-productive time. GeoConvention, pages 5

Mclean MR, Addis MA (1994) Wellbore stability analysis: a review of current methods of analysis and their field application. IADC/SPE Drilling Conf, Houston, pp 261–274

Mohiuddin MA, Khan K (2007) Analysis of wellbore instability in vertical, directional, and horizontal wells using field data. J Petrol Sci Eng 55:83–92

Zhang J, Bai M, Roegiers JC (2003) Dual-porosity poroelastic analyses of wellbore stability. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 40:473–483

Zhang L, Cao P, Radha KC (2010) Evaluation of rock strength criteria for wellbore stability analysis. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 47:1304–1316

Zoback MD (2007) Reservoir geomechanics. First published, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press; ISBN-978-0-521-77069-9

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aslannezhad, M., Khaksar manshad, A. & Jalalifar, H. Determination of a safe mud window and analysis of wellbore stability to minimize drilling challenges and non-productive time. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 6, 493–503 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-015-0198-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-015-0198-2