Abstract

Vulnerability assessment to delineate areas that are more susceptible to contamination from anthropogenic sources has become an important element for sensible resource management and land use planning. It has been recognized for its ability to delineate areas that are more likely than others to become contaminated as a result of anthropogenic activities near the earth’s surface. The main methods of mapping and assessing intrinsic vulnerability in porous media are the following: SI, GOD, SINTACS and DRASTIC. The basic purpose of these maps is to divide an area into more classes, each of which will represent a different dynamic for a specific purpose and use. These models have been used to map groundwater vulnerability to pollution in Hamadan–Bahar aquifer. The results showed in models of DRASTIC, SI, GOD and SINTACS, respectively, 7.1, 44.21, 29.56 and 20.16 percent of the areas are high potential vulnerabilities. According to the model DRASTIC at study area, 33.6% of has a low class of groundwater vulnerability to contamination, whereas a total of 29.4% of the study area has a moderate vulnerability. The final results indicate that the aquifer system in the interested area is relatively protected from contamination on the groundwater surface. The correlation between models shows that DRASTIC model has the highest CI, which is 141, and the GOD model has the highest CI, which is 139. Also, the highest CI for SINTACS and SI is 137 and 136, respectively. Therefore, DRASTIC model is the best model among these models for predicting groundwater vulnerability in Hamadan–Bahar plain aquifer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In many countries with limited sources of water, groundwater is the only water supply. During the last decades, intense agriculture activities and fertilizer applications have resulted in groundwater contamination, which has become a critical issue. In addition to agricultural activities, the release of municipal and industrial wastes has caused an increase in contaminants in the subsurface environment (Gheisari 2017). Recently, groundwater vulnerability mapping is an important key to decision-making processes and improving planning in order to prevent groundwater contamination (Mahvi et al. 2005). Groundwater vulnerability means the degree of protection that the natural environment provides against the spread of pollution in groundwater, is classified into intrinsic and specific vulnerability (National Research Council 1993). To recognize the need for an efficient method to protect groundwater resources from contamination, scientists and managers develop aquifer vulnerability techniques for predicting which areas are the most vulnerable (Mueller et al. 2012; Chenini et al. 2015). During the past years, the assessment of groundwater vulnerability to pollution has been subject to intensive research and a variety of methods have been developed. Many approaches have been developed to evaluate aquifer vulnerability, and for this objective, the GIS and remote sensing tools are combined to various methods: standard DRASTIC, GOD, SINTACS and SI methods (Aller et al. 1987; Van Stempvoort et al. 1992; Foster 1987; Daly and Drew 1999). Also, they are used to evaluate aquifer vulnerability to pollution.

Recently, several methods have been used to investigate the vulnerability of aquifers. Optimization and modification of models have been done with matching models using artificial intelligence methods to achieve suitable maps. A comparative study of the vulnerability maps was performed in order to choose the best method (Teixeira et al. 2015; Chenini et al. 2015). Krishna et al. (2015) assessed the groundwater vulnerability to pollution in Ranchi district, Jharkhand, India. The results showed that the model was validated by comparing the model output with the observed nitrate concentration in water resources in the study aquifer. Al-Abadi et al. (2017) evaluated intrinsic groundwater vulnerability in the shallow aquifer northeastern Missan governorate, south of Iraq by using the DRASTIC model. Some other studies in the field include: Awawdeh et al. (2015) used a modified DRASTIC model to evaluate the vulnerability of groundwater to pollution in Yarmouk River watershed, north Jordan. Rahman (2008) in India; Leal and Castillo (2003) in Mexico; Ghazavi and Ebrahimi (2015) in Iran; Abdullah et al. (2016) in Iraq; Babiker et al. (2005) in Japan. Also, Nadiri et al. (2017, 2018) have been using artificial intelligence methods to evaluate models and vulnerability maps in several areas of Iran. Because of the expansion of agricultural activities, excessive use of chemical fertilizers and the location of industrial and municipal wastewater of Hamadan, it is possible for this aquifer to be polluted. Nitrate, the primary form of nitrogen, is not in the groundwater system naturally, but it can be one of the predominant contaminants associated with agricultural activities. It has high solubility and can easily reach groundwater. Thus, it could be a serious threat to groundwater resources. Therefore, measured nitrate concentrations from monitoring wells can be used to associate and correlate the concentration in the aquifer to the vulnerability index (Gheisari 2017).

The aim of the present study is to assess the aquifer vulnerability of Hamadan–Bahar plain and to recognize the sensitive areas against pollution. Recognizing the vulnerability of groundwater will help to manage their quality and protect groundwater resources. The possibility of pollutants reaching and releasing into the groundwater after contaminating the ground is called the aquifer vulnerability. In this study, an aquifer vulnerability assessment is to identify areas prone to the pollution that were modeled via the DRASTIC, GOD, SINTACS and SI models, and the maps generated for each parameter were classified and combined based on the models.

Materials and methods

A comprehensive groundwater vulnerability model must include parameters to describe how much a site is risky to be contaminated and how the contaminant moves from the contamination site to the aquifer; therefore, numerous vulnerability modeling approaches are proposed. In this study, the vulnerability rating used is the SI, SINTACS, GOD and DRASTIC (Aller et al. 1987; Van Stempvoort et al. 1992; Foster 1987; Daly and Drew 1999; Oroji and Karimi 2018; Oroji 2018). Before starting detailed data collection, some general information pertaining to the hydrology, geology, soil characteristics, geomorphological and water balance was gathered. This information has been used as a base for planning the field data collection and determining the selection of the sample population (Tadesse et al. 2013). The following explained each indicator and how to determine them.

Topography (T): This indicator to the slope percent of the land surface was determined directly from the topographic maps of the Hamadan area (scale 1:50.000) and also using SRTM data and DEM for creating slope raster file. Soil media (S): This index was obtained by digitizing the existing soil maps, with 1:50.000 as a scale required from Hamadan Research and Education Center for Agriculture and Natural Resources which cover the entire region. Net recharges (R): To calculate the recharge parameter distribution, the water table fluctuation method (WTF) was used. One of the major impacts of the integrated watershed management program was on improving groundwater recharge and its availability (Pathak et al. 2013). It estimates groundwater recharge as the product of specific yield, and the annual rate of water table rise added to the total groundwater draft ended by the equivalent permeability, which is found from well logs (Sophocleous 1991).

Depth (D): Its index represents the depth from the land surface to the first groundwater aquifer. It determines the thickness of the material through which infiltrating water must move before reaching the aquifer-saturated zone (Witczak et al. 2004). Consequently, the depth of the groundwater impacts on the interaction degree between the percolating contaminant and subsurface materials and, therefore, on the degree and extent of physical and chemical attenuation, and degradation processes, the depth groundwater distribution (D) was established by subtracting the groundwater level, measured in 35 wells in Hamadan–Bahar aquifer, from the topographic elevation in the corresponding cell location (Rahman 2008). Groundwater depths were interpolated using the Kriging algorithm. A raster map was generated and then categorized into ranges defined by the DRASTIC model. Hydraulic conductivity (C): Due to the unavailability of hydraulic conductivity data in the study area, information of the aquifer media was used to derive the approximate ratings for hydraulic conductivity. It was converted to raster data according to the defined ratings. Aquifer media map was prepared from the geologic map of Hamadan-Bahar plain. Aquifer media in the study area were reclassified into five types and their corresponding ratings were assigned for each aquifer media. The vadose zone characteristics show the attenuation behavior of the materials that are located above the groundwater table and below the soil.

Study area

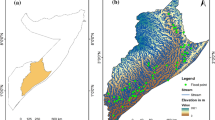

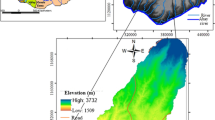

The study area is situated in the Hamadan province and partially in the central province of northwest Iran, with an area of 520 square kilometers covering an area from latitude 34°N to 35° and from longitude 48°E to 49°30′E (Fig. 1). The highest elevation, 3.580 m, occurs at the Kuh-e Alvand south of Hamadan. The lowest elevations, slightly less than 1.500 m, occur along with the water courses on the western margin of the sheet (Akhavan et al. 2011). The output area is located in the northern plains and groundwater with Kabodarahang–Ghahavand the hydrogeological relationship. The most prominent geologic feature is the belt of metamorphic and igneous rocks which trends northwest to southeast. This belt consists largely of Hamadan phyllites with well-developed hornfels near the margins of post-Cretaceous granodiorite intrusions. An area of more mafic igneous material occurs northwest of Hamadan. Paleozoic marbles and Cretaceous crushed limestone and igneous bodies occur in the Zagros thrust belt in the southwestern corner of the sheet. Cretaceous limestone and Oligo-Miocene marbles and limestones occupy the northeastern and southeastern portions of the sheet. Faulting in this area trends northwest to southeast except for the Mesozoic sedimentary zone east of Hamadan where there is north-northeast to south-southwest trend (Akhavan et al. 2011). Figure 2 shows the geological map of the area.

Results and discussion

Using the GIS software, raster map was made from the interpolation of the well data for each indicator. To obtain the vulnerability indexes the corresponding weight and rating according to the formula of each method was given to each indicator. All indicators in different models were mapped (Philes 2004). The slope map is obtained from the digital elevation model, and the map of soils is scanned and then processed from the soil map. Also, all indicators are classified on vulnerability classes with values from the DEM. Distribution maps for each indicator were prepared using the Kriging interpolation technique. The Hamadan–Bahar alluvial aquifer is an important water resource because it is used for irrigation; therefore, the aquifer vulnerability to pollution by generic pollutants has been studied by applying the following methods. After classifications data for each indicator, the spatial mapping in raster format by interpolation of these indicators is a necessary step in this work. All the realized maps were projected in “WGS 1984 UTM Zone 39 N, datum Carthage.”

DRASTIC method

Inherent in each hydrogeological setting are the physical characteristics that affect the groundwater pollution potential. After the factors such as transmissivity, temperature, aquifer chemistry, gaseous phase transport, tortuosity and some others have been evaluated, the most important factors that control the groundwater pollution potential have been determined to be net recharge, soil type, depth to water, topography, aquifer material, impact of the unsaturated zone and aquifer media of the hydraulic conductivity, in short DRASTIC. In the following, a numerical ranking system to assess groundwater pollution potential in the hydrogeological setting has been devised (Aller et al. 1987). It assigns a note between 1 and 10 and a weight between 1 and 5 for each used parameter. For DRASTIC models used Eq. (1).

where DI, vulnerability index; D, depth to water; R, net recharge; A, aquifer material; S, soil media; T, topography; I, vadose zone and C, hydraulic conductivity. The results of this model are shown in Fig. 3.

GOD method

The GOD method is an empirical method for the assessment of aquifer pollution vulnerability developed in Great Britain; this method uses three indicators: overlying lithology, depth to groundwater and groundwater occurrence. Values from 0 to 1 can be assigned to the indicators (Foster 1987). For GOD models used Eq. (2).

where Ci, aquifer type; Ca, saturated zone and Cp, depth. The results of GOD model are shown in Fig. 4.

SINTACS method

The acronym SINTACS stands for the seven indicators included in the method: net recharge, depth to water, vadose zone, slope, hydraulic conductivity, aquifer media and soil media. The SINTACS method was established for hydrogeological, climatic and impacts settings, typical of the Mediterranean countries. In the same way that the DRASTIC method, SINTACS assigns notes and weights for each of these indicators in the following way (Civita and De Maio 2004). For SINTACS models used Eq. (3).

where Iv, vulnerability index; S, depth to water; I, net recharge; N, vadose zone; T, soil type; A, hydrogeological characteristics aquifer; C, conductivity and S, slope. The results of SINTACS model are shown in Fig. 5.

SI method

Specific vulnerability is the term used to define the vulnerability of groundwater to a particular contaminant or group of contaminants. SI method is a vulnerability method for evaluating the specific vertical vulnerability to pollution originated by agricultural activities mainly by nitrates (Ribeiro 2000). SI assigns notes and weight for each of these indicators in the following way. For SI models used Eq. (4).

where SI, vulnerability index; D, depth to water; R, net recharge; A, lithology; T, topography and OS, soil occupation. The indicators mentioned above are defined and determined as follows. The results of SI model are shown in Fig. 6.

After mapping all the indicators, the vulnerability maps were obtained by overlaying the individual maps and calculating the indices on a grid map. The vulnerability index for each grid cell was calculated as the weighted sum of the indicators according to the equation. In the following, we have to evaluate the hydrological settings which are present on the map. Finally, the areas on the final map are labeled with the appropriate hydrogeological setting. The vulnerability indexes for all models are calculated, and the final vulnerability map was subdivided into classes related to vulnerability degrees according to the classification of Engel et al. (1996).

The comparison between DRASTIC, SINTACS, SI and GOD methods shows that the closest results are those from the method SINTACS and SI, modified versions of the DRASTIC method adapted to climate prevailing in the study area. The DRASTIC vulnerability map, according to standard classical, provides, in turn, more detailed results widely different from other methods (Fig. 7). The results showed that the maximum contamination potential in the Hamadan–Bahar plain groundwater was observed in the south, west and northeast borders of the plain. Also, there were areas with very low and low potential in the center, north and east of the plain. Both techniques have prospected the vulnerability potential in Hamadan–Bahar plain with the same accuracy. This region is an area of high agricultural activity with intense use of chemical fertilizers. The DRASTIC map resulting from overlaying the seven thematic maps shows four classes, as indicated in Fig. 7. The highest class of vulnerability index (VI > 200) covers 7.1% of the total surface in the central part of the study area (Table 1). This condition, it is due to the high aquifer permeability coming from the vadose zone sediments nature.

The aquifer combination was of quaternary alluvium and sandstones, medium recharge, shallow groundwater and medium hydraulic conductivity. This results in a low capacity to attenuate the contaminants. Also, very low vulnerability, which is represented by 14.7% of the total Hamadan surface, is essentially due to the deep groundwater, the vadose zone sediments and the low permeability, added to that the low hydraulic conductivity. As well as the low recharge rate, we assume that these are the same conditions in the case of low vulnerability, with less degree of impact for these indicators. The moderate vulnerability represents 29.4% of the study area. Vulnerability pattern is mainly dictated by the variation of the permeability and the vadose zone (Aranyossy 1991). The recharge and the depth of groundwater are two indicators having an influence on vulnerability degrees to pollution. The application of SI, susceptibility index, method indicates the high vulnerable zones to be contaminated by pollutants (Fig. 7). The most vulnerable areas have an indicator between 85 and 100. Zones which have indicator value less than 45 are the less vulnerable (Table 2).

The use of model SINTACS indicates the very high vulnerable zones to be contaminated by pollutants (Fig. 7). The most vulnerable areas have an index between 187 and 210. Zones that have an index value of less than 106 are less vulnerable (Table 2). The GOD model application indicates the very high vulnerable zones to be contaminated by pollutants (Fig. 7). The most vulnerable areas have an index between 0.5 and 0.7 (Table 2). Zones that have an index value between 0.1 and 0.3 are less vulnerable. Statistical comparison among the vulnerability maps generated by each method has been carried out. Figure 7 shows the difference in classification between the used methods of vulnerabilities. This comparison shows a certain similarity between the results obtained using the SINTACS and SI methods (Rahman 2008). Also, the DRASTIC map classification shows different results. We see much more of a class at the DRASTIC method; this method is thus more suitable to use in our case. As shown in the overlapping of the layers, the combination of weighted information layers, models and subsequently a vulnerability map of the area was prepared. Since the ratio of the weights considered for the layers is different, it is necessary to have a criterion for comparing and confirming the proposed combination. For this reason, verification of the models used for the aquifer of the study area was carried out using nitrate concentration. If the nitrate concentration is available at points with suitable dispersion and for a specified period, then the verification step can be done. Nitrate-N concentration was used as all indicators to show whether the vulnerability indexes correctly represent the actual situation in the study area. Also, the maximum acceptable nitrate concentration for human health is 45–50 mg/l (WHO 2008), but it is well known that nitrate concentration higher than 10 mg/l in groundwater indicates anthropogenic contamination. For this work, the concentration of nitrate was classified into four categories: very low, low, medium and high. The alignment of wells with four levels of concentration and predicted vulnerability categories with DRASTIC, GOD, SI and SINCACS models are indicated in Table 3. Based on these results, the DRASTIC model has a higher correlation index. Also, following this model, the GOD model is considered as the appropriate model and has the highest correlation value. The results termed as the correlation index (CI) can indicate the correlation between the model results and nitrate-N concentration in the wells. Higher CI means higher correlation. These results show that the DRASTIC model has the highest CI, which is 141, and the GOD model has the highest CI, which is 139. Also, the highest CI for SINTACS and SI is 137 and 136, respectively. Therefore, the DRASTIC model is the best model among these models for predicting groundwater vulnerability in Hamadan–Bahar plain aquifer (Fig. 7).

Conclusions

Water resources are becoming increasingly scarce, so especially polluted Hamadan–Bahar aquifer located in the center of the Hamadan area in western Iran, which is considered as an economic resource priority because it is used in irrigation and domestic consumption. The area of the aquifer is essentially occupied by agricultural areas characterized by an important use of chemical fertilizers which are in addition to the discharge of industrial zones, ongoing risk to the groundwater quality; this prompts us to a hydrological study and vulnerability late attributed to improving management of water resources in the study area. The use of GIS techniques to identify contamination risk by mapping was primarily due to the automatization of certain operations. The databases which are behind all layers can anytime be updated. Also, the use of GIS facilitates the rapid visualization of some elements in the map by selecting them from the attribute table. The vulnerability maps, contamination data and groundwater quality can be used because of the rapid and correct evaluation of pollution risk. By using this technology, we are assured that the information will be used efficiently. The model’s application showed that Hamadan–Bahar groundwater was characterized by low to high vulnerability degrees. The results of all methods showed that the maximum contamination potential in the Hamadan–Bahar plain groundwater was observed in the south, west and northeast borders of the plain. According to the sensitivity analysis, the depth to the water table was the most effective parameter on the vulnerability potential. There were areas with very low and low potential in the center, north and east of the plain. Both techniques have prospected the vulnerability potential in Hamadan–Bahar plain with the same accuracy. Waters are easily accompanied by various geochemical elements coming from toxic pesticides and their extensive use in farmland and wastewater. So, in high vulnerability areas, we should not allow additional high-risk activities to obtain economic advantage and to reduce environmental pollution hazard.

References

Abdullah TO, Ali SS, Al-Ansari NA (2016) Groundwater assessment of Halabja Saidsadiq Basin, Kurdistan region, NE of Iraq using vulnerability mapping. Arab J Geosci 9:1–16

Akhavan S, Mousavi SF, Abedi-Koupai J, Abbaspour KC (2011) Conditioning DRASTIC model to simulate nitrate pollution case study: Hamadan–Bahar plain. Environ Earth Sci 63:1155–1167

Al-Abadi AM, Al-Shamma’a AM, Aljabbari MH (2017) A GIS-based DRASTIC model for assessing intrinsic groundwater vulnerability in northeastern Missan governorate, southern Iraq. Appl Water Sci 7:89–101

Aller L, Bennet T, Lehr JH, Petty RJ, Hachet G (1987) DRASTIC: a standardized system for evaluating groundwater pollution potential using hydrogeologic settings (EPA 600/2-87). Environmental Research Laboratory, Office of Research and Development, US Environmental Protection Agency Report, Tucson, p 622

Aranyossy JF (1991) The contribution of isotope techniques to study the recharge under constraints techniques and climate extremes. Diploma for Accreditation to Supervise Research in Sciences, University of Paris sud, Orsay, p 576

Awawdeh M, Obeidat M, Zaiter G (2015) Groundwater vulnerability assessment in the vicinity of Ramtha wastewater treatment plant, North Jordan. Appl Water Sci 5:321–334

Babiker IS, Mohamed MA, Hiyama T, Kato K (2005) A GIS-based DRASTIC model for assessing aquifer vulnerability in Kakamigahara Heights, Gifu Prefecture, and central Japan. Sci Total Environ 345:127–140

Chenini I, Zghibi A, Kouzana L (2015) Hydrogeological investigations and groundwater vulnerability assessment and mapping for groundwater resource protection and management: state of the art and a case study. J Afric Earth Sci 109:11–26

Civita M, De Maio M (2004) Assessing and mapping groundwater vulnerability to contamination: the Italian “combined” approach. Geofis Int 43:513–532

Daly D, Drew D (1999) Irish methodologies for karst aquifer protection. In: Beek B (ed) Hydrogeology and engineering geology of sinkholes and karst. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 267–272

Engel B, Navulur K, Cooper B, Hahn L (1996) Estimating groundwater vulnerability to non-point source pollution from nitrates and pesticides on a regional scale. In: Kovar K, Nachtnebel HP (eds) Application of geographic information systems in hydrology and water resources management. IAHS Press, Wallingford, pp 521–526

Foster SSD (1987) Fundamental concepts in aquifer vulnerability, pollution risk and protection strategy. In: van Duijvenbooden W, van Waegeningh HG (eds) Proceedings and information in vulnerability of soil and ground-water to pollutants, vol 38. TNO Committee on Hydrological Research, The Hague, pp 69–86

Ghazavi R, Ebrahimi Z (2015) Assessing groundwater vulnerability to contamination in an arid environment using DRASTIC and GOD models. Int J Environ Sci Technol 12:2909–2918

Gheisari N (2017) Groundwater vulnerability assessment using a GIS-based modified DRASTIC model in agricultural areas. Thesis, University of Ottawa, p 100

Krishna R, Iqbal J, Gorai AK, Pathak G, Tuluri F, Tchounwou PB (2015) Groundwater vulnerability to pollution mapping of Ranchi district using GIS. Appl Water Sci 5:345–358

Leal JAR, Castillo RR (2003) Aquifer vulnerability mapping in the Turbio river valley, Mexico: a validation study. Geofí Inter 42:141–156

Mahvi AH, Nouri J, Babael AA, Nabizadeh R (2005) Agricultural activities impact on groundwater nitrate pollution. Int J Environ Sci Technol 2:41–47

Mueller NC, Braun J, Bruns J, Černík M, Rissing P, Rickerby D, Nowack B (2012) Application of nanoscale zero valent iron (NZVI) for groundwater remediation in Europe. Environ Sci Pollut Res 19:550–558

Nadiri AA, Gharekhani M, Khatibi R, Sadeghfam S, Moghaddam AA (2017) Groundwater vulnerability indices conditioned by supervised intelligence committee machine (SICM). Sci Total Environ 574:691–706

Nadiri AA, Sedghi Z, Khatibi R, Sadeghfam S (2018) Mapping specific vulnerability of multiple confined and unconfined aquifers by using artificial intelligence to learn from multiple DRASTIC frameworks. J Environ Manag 227:415–428

National Research Council (1993) Groundwater vulnerability assessment, contaminant potential under conditions of uncertainty. National Academy Press, Washington

Oroji B (2018) Assessing groundwater vulnerability by pollution mapping in Iran: case study Hamadan–Bahar plain. Geofí Inte 57(3):161–174

Oroji B, Karimi ZF (2018) Application of DRASTIC model and GIS for evaluation of aquifer vulnerability: case study of Asadabad, Hamadan (westernIran). Geosci J 22:843–855

Pathak P, Chourasia AK, Wani SP, Sudi R (2013) Multiple impact of integrated watershed management in low rainfall semi-arid region: a case study from Eastern Rajasthan, India. J Water Resour Protect 5:27–36. https://doi.org/10.4236/jwarp.2013.51004

Philes CJ (2004) The geostatistical modeling of spatial variability and its applications. Thesis, University Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, p 71

Rahman A (2008) A GIS based DRASTIC model for assessing groundwater vulnerability in shallow aquifer in Aligarh, India. Appl Geograph 28:32–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2007.07.008

Ribeiro L (2000) Desenvolvimento de um ı´ndice para avaliar a susceptibilidade, ERSHA-CVRM, p 8

Sophocleous MA (1991) Combining the soil water balance and 475 water level fluctuation methods to estimate natural groundwater recharge: practical aspects. J Hydro 124:229–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(91)90016-B

Tadesse A, Bosona T, Gebresenbet G (2013) Rural water supply management and sustainability: the case of Adama Area, Ethiopia. J Water Resour Protect 5:208–221. https://doi.org/10.4236/jwatp.2013.52022

Teixeira J, Chaminé HI, Marques JE et al (2015) A comprehensive analysis of groundwater resources using GIS and multicriteria tools (Caldas da Cavaca, Central Portugal): environmental issues. Environ Earth Sci 73:2699–2715

Van Stempvoort D, Ewert L, Wassenaar L (1992) AVI: a method for groundwater protection mapping in the Prairie Provinces of Canada. Prairie Provinces Water Board Report 1-14, Regina, SK

Witczak S, Duda R, Zurek A (2004) The Polish concept of groundwater vulnerability mapping. In: Witkowski AJ, Kowalczyk A, Vrba J (eds) Groundwater vulnerability assessment and mapping, International conference of groundwater vulnerability assessment and mapping, Ustron, pp 62–76

World Health Organization (WHO) (2008) Guidelines for drinking-water quality. Third edition incorporating first and second addenda, vol. 1, Recommendations. World Health Organization, Geneva

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mohsen Ghasemi Jahromi of University of Tehran for his insight and direction on this project, as well as Hashem Karimi of the Agricultural research, education & extension organization for his assistance in determining geologic characteristics and processes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Oroji, B. Groundwater vulnerability assessment with using GIS in Hamadan–Bahar plain, Iran. Appl Water Sci 9, 196 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-019-1082-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-019-1082-x