Abstract

Access to potable water for the common people is one of the most challenging tasks in the present era. Contamination of drinking water has become a serious problem due to various anthropogenic and geogenic events. The paper demonstrates the application of evolutionary algorithms, viz., particle swan optimization and genetic algorithm to 24 water samples containing eight different heavy metal ions (Cd, Cu, Co, Pb, Zn, Ar, Cr and Ni) for the optimal estimation of electrode and frequency to classify the heavy metal ions. The work has been carried out on multi-variate data, viz., single electrode multi-frequency, single frequency multi-electrode and multi-frequency multi-electrode water samples. The electrodes used are platinum, gold, silver nanoparticles and glassy carbon electrodes. Various hazardous metal ions present in the water samples have been optimally classified and validated by the application of Davis Bouldin index. Such studies are useful in the segregation of hazardous heavy metal ions found in water resources, thereby quantifying the degree of water quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Establishment of different industries such as fertilizers, paper, metal plating, batteries, mining operations and tanneries has been causing an increased rate of discharge of the most hazardous inorganic pollutants known as heavy metal ions (HMI) in the water resources. As a result, the origin of these pollutants is better to be considered as anthropogenic rather than natural (Kumar et al. 2012a, b, 2014, 2015, 2016; Karkra et al. 2016). These pollutants have been deteriorating the quality of water resources. These toxic elements are non-biodegradable and primarily enter the body through water, followed by food and air. They are toxic even at low concentration level and their toxicity increases with accumulation in water (Bradl 2004); if accumulated in living organisms, they can cause dreadful diseases such as Alzheimer, Parkinson, kidney damage and hypertension. As these diseases are pernicious, proper surveillance systems are required not only to detect, but also to perform the remedial process of removal of HMI. Many government agencies have come forward and employed stringent rules and regulations as these toxic ions are some of the high priority pollutants and are becoming the most serious environmental problems. The metal ions released by industries are copper, arsenic, nickel, cadmium, mercury, chromium and cobalt (Fu and Wang 2011), which are of major concern. According to a report by the Indian National Science Academy (Sahni 2011), these ions are found in many areas and it lists that 80% of the toxic pollutants in India are primarily contributed by Gujarat, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh as shown in Table 1. For the scientist community, it has become the biggest challenge for preserving our natural heritage, i.e., rivers such as Yamuna from being affected by the adverse effects of these pollutants ; the largest tributary of the Ganges is now the second most polluted river in India after Ganges (Kumar et al. 2014; Chawla et al. 2015).

Nowadays, the qualitative and quantitative study of liquids is done using a multi-sensor array system called e-Tongue device. In 1985, Otto and Thomas presented the first e-tongue system (Otto and Thomas 1985). The inspiration behind the design and operation of electronic tongues (ET) systems is the neurophysiology of the senses of taste. This system not only performs the automatic analysis of samples with complicated composition and finds their distinguishable characteristic properties, but also performs a faster qualitative analysis. There is a fusion of knowledge from various branches of science like pattern recognition methods, sensory technologies, chemo-metric tools and artificial intelligence in the construction of such systems. In the design of electronic tongues, a wide variety of chemical sensors can be employed: electrochemical (potentiometric, voltammetric), enzymatic (biosensors) or optical. There are various analytical methods that have been used for HMI determination including atomic fluorescence spectroscopy, atomic absorption spectroscopy and inductively coupled plasma-mass spectroscopy (Sanchez-Rodas et al. 2010; Larivière et al. 2012). The potentiometric method has been used for measuring and monitoring HMI in rivers (Mimendia et al. 2010a) and can be applied to evaluate cross-sensitivity of any kind of potentiometric sensors for liquid media (Vlasov et al. 1997). The major drawbacks of such potentiometric measurements are the property of temperature dependency, which influences the changes in solution, and adsorption of solution components, which further has effect on the nature of charge transfer; however, the effects of those factors can be minimized by controlling the temperature (Ciosek and Wroblewski 2007). There is another technique called electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) that exploits Faraday’s law to obtain electrical measurements for the chemical process. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy is one of the highly used non-selective techniques for heavy metal detection due to its several advantages over other techniques. It offers better sensitivity and is easy to use compared to other techniques. The main advantage of this technique is the cost-effectiveness. EIS measures the impedance of all heavy metals by applying AC perturbation and the sweep of frequency from 1 Hz to 100 kHz (Reece 2005). EIS is one of the widely used techniques and gives the physio-chemical information of contaminated samples and the resulting multi-variate dataset contain all the hidden patterns and set of information that are needed to be explored. With the help of the chemometrics method in combination with other optimizing algorithm, data processing and information extraction from chemical data are carried out (Reece 2005).

Over a period of time, there have been many applications areas where genetic algorithm has been used for optimal classification (Vlasov et al. 1997; Turek et al. 2009; Mimendia et al. 2010a, b; Wilson et al. 2012). The general application areas are in samples of tea, juice (Liu et al. 2013), wine and water containing HMI. Prominent works done by Bhondekar et al. (2011), (Kaur et al. 2012) and (Kumar et al. 2012a, b) in the field of optimum classification of tea have used techniques such as social impact theory-based optimizer and support vector machines. Similarly, Gutiérrez et al. (2011) used principal component analysis (PCA) and soft independent modeling by class analogy (SIMCA) for the quantification of grape varieties. Further, Jańczyk et al. (2010) used ion selective electrode for detection of micro-encapsulation effect of pharmaceutical ingredients. As far as the classification of water containments are concerned, Martínez-Máñez et al. (2005) developed an electronic tongue for the qualitative analysis of natural waters using Fuzzy ARTMAP neural network with success rate higher than 93%. Hong Men et al. (2005) have developed an integrated electronic tongue which includes multiple light addressable potentiometric sensors and electrochemical electrodes for the detection of Fe(III), Cr(VI) and HMI.

Though evolutionary algorithms such as genetic algorithm (GA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm have been used since a long time in several applications, in most of the cases PSO remains to be one of the best optimizers. The potential of GA and PSO for classification of the water containments is yet to be harnessed. The novelty of the work lies in the application of GA and PSO to the multi-variate data pertaining to multi-electrode, multi-frequency potable water data for the classification of heavy metal ions. This work focuses on classifying the impedance data of potable water of single electrode multi-frequency (SEMF), single frequency multi-electrode (SFME) and multi-frequency multi-electrode (MFME) and GA, with PSO being used to optimize MFME response. Principal component analysis (PCA) improves the extraction of the cluster structure (Ben-Hur and Guyon 2003) and is applied in conjunction with cluster validation-similarity index (S), dissimilarity index (D) and Davis–Bouldin index (DBI). The results show that the impedance response of silver nanoparticle (SNP) electrode gives the best discriminability without compromising the complexity of the system, for e.g., using SFME, MFME and GA and PSO optimized response. Overall, PSO optimized the result with the best combination of electrodes with particular frequencies for classification. It also shows that we can improve the cross-sensitivity of electrodes by selecting the optimum frequency of the optimum electrode.

Methodology

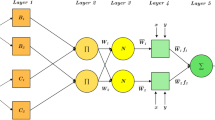

The schematic of the work carried out is depicted in Fig. 1.

Experimental setup and data acquisition

The experimental setup is designed to obtain the impedance spectra of eight heavy metal ions sampled from reagents such as NiCl2, ZnCl2, CuCl2·2H2O, K2Cr2O7 (Spectrochem Pvt. Ltd.), CdSO4·8H2O, As2O3 and AgNO3 (Merck Pvt. Ltd.) (3 samples for each) at 60 different frequency ranges from 1 Hz to 100 kHz using electrochemical workstation instrument. All the experiments were carried out at room temperature and the electrodes Au, GC, Pt and SNP were first polished with alumina slurry and dried in N2 gas after the removal of residual alumina by sonication in isopropanol. Further, the impedance spectra of different heavy metal ions were recorded. The recorded data are in the form of matrix of size 24 × 60 for each electrode, where rows indicate 24 different sampled heavy metal ions and columns represent their sampled frequency points. The feature selection and cluster analysis of recorded impedance spectra were done using PCA and validated using clustering indices.

Feature selection: principal component analysis

Principal component analysis is a statistical tool used for dimensionality reduction of multi-variate data. It selects the features from input data to reduce the dimensionality and tries to keep the informative value of the data intact. Depending on the number of input variables, it creates principal components (PC’s) representing the maximum variability in information data and its variance in descending order (PC1, PC2, PC3, etc.). Usually, the first two components (PC1 and PC2) are found to be the best means to carry out the classification of input variables. In our work, we performed PCA to form clusters of impedance values of the electrodes at various frequencies, and analysis and validation of the cluster through the similarity and dissimilarity factor within the cluster and in between clusters, respectively.

Clustering analysis

Clustering is an unsupervised process of dividing or grouping set of input data on the basis of some common attributes into clusters. It is very difficult to define the acceptability of clusters due to which two measurements are generally done:

-

Similarity Index (compactness) (S)—This index measures the value of homogeneity of data in a cluster and how much it is closely packed in a given cluster. This compactness factor is generally measured using the variance.

-

Dissimilarity Index (separation) (D)—This index measures the value of heterogeneity between the clusters and how far clusters are from each other. The more the distance between the clusters, the better is the clustering.

To measure crisp clustering, i.e., having no overlapping partitioning, one more validity index is used, i.e., Davies–Bouldin index (DBI) (Kovács and Iváncsy 2006), which is based on the similarity and dissimilarity measure of the clusters.

Let E be the set of input data, and C i the cluster of E i , i.e., \(E_{i} \in C_{i}\).Then the similarity index (S i ) of C i is measured as

where N i is the number variable in C i and T i the centroid of C i .

Similarly, we can measure the dissimilarity index (D i ):

where k r represents the kth element of centroid T r of cluster C r and p = 2 (Euclidian distance).

To calculate R ij we need to find the similarity between two clusters, C i and C j :

Data processing

The four electrodes (platinum, gold, glass carbon and silver nanoparticles) are used in experimentation and impedance is measured in the range of 1 Hz to 100 kHz in 60 steps in response to the potable water mixture containing eight heavy metal ions dissolved (1 metal ion has 3 samples). We use only five frequencies to carry out further analysis to reduce impedance variables. The data are then arranged in 24 × 5 matrices for each electrode and each frequency, where rows represent heavy metal ions and columns are the modulus of impedance of electrodes with respect to frequencies, matrices namely GC, Au, Pt and SNP and frequencies 1, 100 Hz, 1, 10 and 100 kHz. Further, a matrix containing the data of all electrodes is formed named as multi-frequency multi-electrode (MFME) of size 20 × 24, where rows represent a sample and column the impedance response of each electrode to a particular frequency. The above matrices have been standardized (i.e. mean centered and standard deviation scaled). To optimize MFME data, it is subjected to GA and PSO. It was observed that using DBI as their fitness function, both GA and PSO select different sets of electrodes, i.e., GA selected Au—1 Hz, Au—1 kHz, SNP—1 Hz, Pt—10 kHz and Pt—100 Hz; and PSO selected electrodes Pt—100 kHz, Pt—1 kHz, Au—100 kHz, Au—10 kHz and SNP—100 Hz. For all matrices, the similarity index (S), dissimilarity index (D) and Davies–Bouldin index (DBI) values are calculated and shown in Table 2.

Results and discussions

To analyze the impedance values generated by the electrochemical workstation used in the experiment, we have used PCA to classify the heavy metal ions and genetic algorithm to check the cross-sensitivity of the electrodes. We used four electrodes, namely, platinum (Pt), glassy carbon (GC), gold (Au) and silver nanoparticles (SNPs). The eight heavy metal ions are arsenic, copper, zinc, nickel, cadmium, lead, cobalt and chromium. For each electrode, we had 24 impedance values corresponding to three sample sets of eight heavy metal ions. The frequencies used are 1, 100 Hz, 1, 10 and 100 kHz. For each frequency, we have impedance values in the form of a matrix of size 3 × 8 for each electrode. Such a matrix corresponds to the data pertaining to single frequency multi-electrode (SFME) configuration. The PCA scattering corresponding to the SFME configuration for frequencies 1, 100 Hz, 1, 10 and 100 kHz are shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, respectively.

It can be seen from Fig. 2 that two heavy metal ions—Co and Cr, are clearly classified at 1 Hz frequency, and the rest of the metal ions overlap and as a result are not properly classified. Figure 3 shows that all the heavy metal ions are reasonably classified at a frequency of 100 Hz. Figure 4 classifies As, Pb, Cu, Cd and Zn as forming a more compact cluster at 1 kHz, whereas the Co, Ni and Cr compactness of clusters is comparatively less as compared to the cluster formed at 100 Hz frequency. Figure 5 classifies all the heavy metal ions; the plot is quite similar to that of 1 kHz. The impedance values at 100 kHz are not that well classified, as overlapping was present between Co and Cd as shown in Fig. 6. When the similarity and dissimilarity indices are compared for all the frequency values used, it can be observed that the classification corresponding to 1 kHz is the most reasonable, as it has lower S (similarity index) value and higher D (dissimilarity index) value among all the five frequencies in the SFME.

The next configuration we have considered is multi- frequency single electrode (MFSE). For each of the four electrodes, Pt, GC, Au and SNP, the five frequencies used are 1, 100 Hz, 1, 1 and 100 kHz. The PCA scatterings of MFSE configuration for each electrode are shown in Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10.

Figures 7 and 8 show the PCA scattering corresponding to the Pt electrode and GC electrode, respectively, and the classification is very poor because of excessive overlapping. Figure 9 shows a better classification, but overlapping exists. Figure 10 shows the best classification of metal ions when SNP electrode is used. Out of all the four electrodes, SNP clearly stands out as the most optimal electrode in the MFSE configuration for classification of heavy metal ions with the smaller S value as 0.429 and a larger D value as 2.816 (Table 2).

The third configuration we have used is multi-frequency multi-electrode (MFME) whose PCA scattering is shown in Fig. 11.

Every heavy metal ion Cd, Co, Zn, Ni, Cu, Cr, Ar and Pb form its own clusters as can been seen and to decrease the complexity of the MFME configuration and to optimize the issue of cross-sensitivity of electrodes, i.e., choosing optimum electrode at its optimum frequency, we have used the GA and PSO algorithm.

The GA and PSO algorithm was tuned and ran several times and selected the electrodes with the best efficiency on the basis of DBI as the fitness function. The electrodes selected by GA are Pt—1 kHz, SNP—100 kHz, Au—1 kHz, GC—1 Hz and GC—1 kHz. The matrix of 24 × 5 was formed containing the electrode impedance values at the particular selected frequency by GA and PCA scatter plot of MFME. GA successfully classified the ions and the clusters formed were more compact as compared to both MFME and SNP results as seen in Fig. 12.

Further, we have repeated a similar exercise for the electrodes (Pt—100 kHz, Pt—1 kHz, Au—100 kHz, Au—10 kHz and SNP—100 Hz) selected by PSO. It is observed that clusters of nickel and chromium ions that were not optimized in the GA scatter plot are now more compact in the MFME PSO PCA scatter plot shown in Fig. 13.

Further, the matrix containing these electrodes of each optimization technique was subjected to a code written in MATLAB to calculate the cluster indices. It was found that MFME–PSO produced a comparatively better result as compared to all, both similarity index (S) and Davis–Bouldin index (DBI) decreased, which represents a better classification of ions.

Conclusions

In this work in the SEMF system, it is found that SNP gives better classification of HMI as compared to Pt, GC and Au. Overall, the PSO-optimized response gives better clustering indices values; its system complexity is more, as multiple electrodes are used, but classification and compactness of the clusters formed is much more distinguishable as compared to SNP. The PSO-optimized multi-frequency multi-electrode system could be used for discrimination of heavy metal ions residing in potable water. Also, it is important to keep in consideration that cross-sensitivity of electrodes could enhance more and opens up the window for more qualitative and quantitative analysis of liquids for exploration.

References

Ben-Hur A, Guyon I (2003) Detecting stable clusters using principal component analysis. In: Brownstein MJ, Khodursky AB (eds) Functional genomics: methods and protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, pp 159–182

Bhondekar AP, Kaur R, Kumar R, Vig R, Kapur P (2011) A novel approach using Dynamic Social Impact Theory for optimization of impedance-Tongue (iTongue). Chemometr Intell Lab Syst 109(1):65–76

Bradl HB (2004) Adsorption of heavy metal ions on soils and soils constituents. J Colloid Interface Sci 277(1):1–18

Chawla P, Kumar P, Singh M, Hasteer N, Ghanshyam C (2015) Prediction of pollution potential of Indian rivers using empirical equation consisting of water quality parameters. In: 2015 IEEE Technological Innovation in ICT for Agriculture and Rural Development (TIAR)

Ciosek P, Wroblewski W (2007) Sensor arrays for liquid sensing—electronic tongue systems. Analyst 132(10):963–978

Fu F, Wang Q (2011) Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: a review. J Environ Manag 92(3):407–418

Gutiérrez M, Domingo C, Vila-Planas J, Ipatov A, Capdevila F, Demming S, Büttgenbach S, Llobera A, Jiménez-Jorquera C (2011) Hybrid electronic tongue for the characterization and quantification of grape variety in red wines. Sens Actuators B Chem 156(2):695–702

Jańczyk M, Kutyła A, Sollohub K, Wosicka H, Cal K, Ciosek P (2010) Electronic tongue for the detection of taste-masking microencapsulation of active pharmaceutical substances. Bioelectrochemistry 80(1):94–98

Karkra R, Kumar P, Bansod BKS, Krishna CR (2016) Analysis of heavy metal ions in potable water using soft computing technique. Proc Comput Sci 93:988–994

Kaur R, Kumar R, Gulati A, Ghanshyam C, Kapur P, Bhondekar AP (2012) Enhancing electronic nose performance: a novel feature selection approach using dynamic social impact theory and moving window time slicing for classification of Kangra orthodox black tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze). Sens Actuators B Chem 166–167:309–319

Kovács F, Iváncsy R (2006) Cluster validity measurement for arbitrary shaped clusters. In: Proceedings of the 5th WSEAS international conference on artificial intelligence, knowledge engineering and data bases, World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society (WSEAS)

Kumar P, Bhondekar AP, Kapur P (2012) Modelling and estimation of spatiotemporal surface dynamics applied to a middle Himalayan region. Int J Comput Appl 54(7):17–24

Kumar R, Bhondekar AP, Kaur R, Vig S, Sharma A, Kapur P (2012b) A simple electronic tongue. Sens Actuators B Chem 171–172:1046–1053

Kumar P, Bhondekar AP, Kapur P (2014) Measurement of changes in glacier extent in the Rimo glacier, a sub-range of the Karakoram Range, determined from Landsat imagery. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci 26(1):121–130

Kumar P, Bansod BKS, Debnath SK, Thakur PK, Ghanshyam C (2015) Index-based groundwater vulnerability mapping models using hydrogeological settings: a critical evaluation. Environ Impact Assess Rev 51:38–49

Kumar P, Thakur PK, Bansod BKS, Debnath SK (2016) Assessment of the effectiveness of DRASTIC in predicting the vulnerability of groundwater to contamination: a case study from Fatehgarh Sahib district in Punjab, India. Environ Earth Sci 75(10):879

Larivière D, Tremblay M, Durand-Jézéquel M, Tolmachev S (2012) Detection of beryllium in digested autopsy tissues by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry using a high matrix interface configuration. Anal Bioanal Chem 403(2):409–418

Liu M, Wang M, Wang J, Li D (2013) Comparison of random forest, support vector machine and back propagation neural network for electronic tongue data classification: application to the recognition of orange beverage and Chinese vinegar. Sens Actuators B Chem 177:970–980

Martínez-Máñez R, Soto J, Garcia-Breijo E, Gil L, Ibáñez J, Llobet E (2005) An “electronic tongue” design for the qualitative analysis of natural waters. Sens Actuators B Chem 104(2):302–307

Men H, Zou S, Li Y, Wang Y, Ye X, Wang P (2005) A novel electronic tongue combined MLAPS with stripping voltammetry for environmental detection. Sens Actuators B Chem 110(2):350–357

Mimendia A, Gutiérrez JM, Leija L, Hernández PR, Favari L, Muñoz R, del Valle M (2010a) A review of the use of the potentiometric electronic tongue in the monitoring of environmental systems. Environ Model Softw 25(9):1023–1030

Mimendia A, Legin A, Merkoçi A, del Valle M (2010b) Use of Sequential Injection Analysis to construct a potentiometric electronic tongue: application to the multidetermination of heavy metals. Sens Actuators B Chem 146(2):420–426

Otto M, Thomas JDR (1985) Model studies on multiple channel analysis of free magnesium, calcium, sodium, and potassium at physiological concentration levels with ion-selective electrodes. Anal Chem 57(13):2647–2651

Reece C (2005) An introduction to electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. https://www.jlab.org/conferences/tfsrf/Thursday/Th2_1-EIS%20intro%20Reece.pdf

Sahni SK (2011) Hazardous metals and minerals pollution in india: sources, toxicity and management. A position paper, Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi

Sanchez-Rodas D, Corns WT, Chen B, Stockwell PB (2010) Atomic fluorescence spectrometry: a suitable detection technique in speciation studies for arsenic, selenium, antimony and mercury. J Anal At Spectrom 25(7):933–946

Turek M, Heiden W, Riesen A, Chhabda TA, Schubert J, Zander W, Krüger P, Keusgen M, Schöning MJ (2009) Artificial intelligence/fuzzy logic method for analysis of combined signals from heavy metal chemical sensors. Electrochim Acta 54(25):6082–6088

Vlasov Y, Legin A, Rudnitskaya A (1997) Cross-sensitivity evaluation of chemical sensors for electronic tongue: determination of heavy metal ions. Sens Actuators B Chem 44(1–3):532–537

Wilson D, del Valle M, Alegret S, Valderrama C, Florido A (2012) Potentiometric electronic tongue-flow injection analysis system for the monitoring of heavy metal biosorption processes. Talanta 93:285–292

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support extended by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi, under Project ESC-0306-Clean Water. The authors would like to thank all the staff at CSIR-CSIO for their cooperation in all respects. The authors are also grateful to all the staff of NITTTR Chandigarh for their valuable suggestions. The authors would also like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for reviewing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Karkra, R., Kumar, P., Bansod, B.K.S. et al. Classification of heavy metal ions present in multi-frequency multi-electrode potable water data using evolutionary algorithm. Appl Water Sci 7, 3679–3689 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-016-0514-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-016-0514-0