Abstract

Studies of microbial associations of intertidal isopods in the primitive genus Ligia (Oniscidea, Isopoda) can help our understanding of the formation of symbioses during sea-land transitions, as terrestrial Oniscidean isopods have previously been found to house symbionts in their hepatopancreas. Ligia pallasii and Ligia occidentalis co-occur in the high intertidal zone along the Eastern Pacific with a large zone of range overlap and both species showing patchy distributions. In 16S rRNA clone libraries mycoplasma-like bacteria (Firmicutes), related to symbionts described from terrestrial isopods, were the most common bacteria present in both host species. There was greater overall microbial diversity in Ligia pallasii compared with L. occidentalis. Populations of both Ligia species along an extensive area of the eastern Pacific coastline were screened for the presence of mycoplasma-like symbionts with symbiont-specific primers. Symbionts were present in all host populations from both species but not in all individuals. Phylogenetically, symbionts of intertidal isopods cluster together. Host habitat, in addition to host phylogeny appears to influence the phylogenetic relation of symbionts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Eukaryotes in a number of phyla have overcome their limitations in nutritional capabilities by associating with microorganisms. Nutritional symbioses are particularly common in animals feeding on diets that are either limited in essential amino acids and vitamins, or that are otherwise difficult to digest (e.g.Buchner 1965; Breznak and Brune 1994; Douglas 1994; Lau et al. 2002; Dillon and Dillon 2004). For example, lignin, cellulose, and other polymers—resistant to degradation by animal digestive enzymes—are digested by bacterial and fungal enzymes in the gut of herbivorous mammals and arthropods (Breznak and Brune 1994; Douglas 1994; Zimmer et al. 2001, 2002). Novel metabolic capabilities acquired by one organism from its microbial partner can allow the hosts to expand their distribution and occupy hitherto unfilled niches (Douglas 1994). Thus animal microbe associations can be important drivers of evolution (Doebeli and Dieckmann 2000; Buckling and Rainey 2002; Leonardo and Muiru 2003).

Because they can be found in habitats ranging from strictly marine to strictly terrestrial (Abbott 1939; Edney 1968), isopods (Arthropoda, Crustacea, Malacostraca, Pericaridea) are a good system to study changes in bacterial gut community composition between related taxa living in different environments. Oniscidean isopods—important in litter decomposition on land—are the only one of ten isopod suborders where the majority of species have become independent of the aquatic environment. This transition from sea to land is believed to have occurred through the high intertidal or supra-littoral zone (Sutton and Holdich 1984), and today primitive oniscidean isopods in the Ligiidae remain in intertidal habitats (Schmalfuss 1989). Thus Ligia spp. can serve as model organisms for the transition from a marine to a terrestrial existence (Schmalfuss 1978; Carefoot and Taylor 1995).

The separation of the isopod digestive system into different microhabitats is relevant in terms of its functional significance (Hames and Hopkin 1989). In terrestrial isopods, bacteria have been found closely associated with the hepatopancreas, or digestive midgut gland involved in the secretion of digestive enzymes and the absorption of nutrients (Hopkin and Martin 1982; Wood and Griffiths 1988; Fraune and Zimmer 2008). No such symbionts have been found in subtidal isopods (Zimmer et al. 2001, 2002). Two novel symbionts from the hepatopancreas of the terrestrial Porcelia scaber (Oniscidea) have been described (Wang et al. 2004a, 2004b); but these bacteria remain uncultured and were thus assigned Candidatus status (Neimark et al. 1998). Ecdysis is a disruptive force for the development of a stable bacteria-host association, as both the fore- and hindgut of isopods are shed and need to be re-colonized with a bacterial community following this process. The establishment of a more stable bacterial community can be expected in the midgut that does not undergo ecdysis (Zimmer 2002). Symbiotic bacteria in the hepatopancreas of Oniscidean isopods have been associated with cellulose digestion and phenol oxidation (Zimmer and Topp 1998; Zimmer et al. 2002), and appear to confer increased survival under conditions of low quality diet (Fraune and Zimmer 2008).

Little is known about the association of primitive intertidal oniscidean isopods with microbes despite the premise that the acquisition of symbionts was a key step in the sea-land transition of isopods (Zimmer et al 2002). Isopods in the Ligiidae are living today in the high intertidal, a transition zone between marine and terrestrial habitats. Findings of microbial associations of isopods in the Ligiidae so far have been inconclusive (Wang et al. 2007; Fraune and Zimmer 2008), and the occurrence of symbionts in this family has been considered rare based on limited data (Fraune and Zimmer 2008). The current study investigates the presence, identity, and distribution of microbial symbionts in the hepatopancreas of two oniscidean isopods Ligia pallasii and Ligia occidentalis. This genus is considered primitive among Oniscidean isopods (Mattern and Schlegel 2001), and Ligia species worldwide are confined to the extreme high intertidal or supralittoral zone (Carefoot and Taylor 1995; Schmalfuss 2003). It is unknown whether all Ligia species have symbionts in the hepatopancreas, and whether specificity exists between host and symbionts for this group. Existing studies of symbiont distribution in isopods cover only small geographic areas (Zimmer et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2007; Fraune and Zimmer 2008). This study addresses the question of symbiont prevalence by screening for symbionts in two closely related and ecologically similar isopod hosts over a large geographic range of partially overlapping host distributions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection

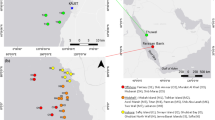

Both Ligia pallasii and Ligia occidentalis occur in the Eastern Pacific and are typically encountered in the upper reaches of the intertidal zone. The northern L. pallasii can be found from Alaska to central California, and the southern L. occidentalis from southern Oregon to Baja California (Schmalfuss 2003). A wide geographic region of sympatry occurs between southern Oregon and central California (Fig. 1).

Sampling sites for symbiont screens of Ligia pallasii and L. occidentalis hosts. Station IDs identify sampling locations as used in Table 1. Area between arrows marks the sympatric range of the host species. The range distribution of Ligia pallasii (black line) and Ligia occidentalis (grey line) is shown in inset with area of sampling location marked by dotted line

Adult isopods were collected between November 2008 and June 2009 in the high rocky intertidal at 20 locations along an approximately 1,900 km stretch of the Eastern Pacific coastline (from Eagle Cove (EC) in the San Juan Islands, Washington, USA 48.46°N, 123.03°W to Erendira (ER) in northern Baja California, Mexico 31.87°N, 116.38°W) (Table 1). Ten sampling stations were located in the presumed zone of range overlap of both Ligia species (Schmalfuss 2003). Whenever possible, isopods were collected from multiple locations within a site, usually within 500 meters of each other. All isopods were collected by hand and kept alive in isolated containers in the laboratory for a maximum of three days prior to dissection.

2.2 DNA extraction, PCR amplification and cloning

Ligia pallasii and L. occidentalis, collected from Bodega Bay (38.32°N, 123.06°W) in the central range of the distribution, were used to create 16S rRNA clone libraries of microbial symbionts. The hepatopancreas of five individual isopods of each species was dissected using sterile techniques. Each isopod was washed 5x in distilled water and the outside sterilized with 70% ethanol (2 rinses) prior to dissection. Only healthy adult individuals, both male and female, that were not molting were used for dissection. Genomic DNA was extracted with a MoBio Power Soil® DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA), checked for quality and quantified against a standard of known concentration on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. DNA was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified with universal bacterial 16S rRNA gene primers 8f (5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′) and 1492r (5′-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3′). PCR reactions contained 12.5 μl Promega master mix (2x) (Promega, Madison WI), 2 μl of each primer (15 pmol), approximately 25 ng of template DNA and nuclease free water to a final reaction volume of 25 μl and were run on a Bio-Rad Thermocyler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with the following profile: Initial Denaturation 95°C for 5 min, 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 46°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1.5 min, followed by a final extension of 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were visualized on 1.2% agarose gels and products of correct size were purified with ExoSAP-IT® (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH). Purified PCR products from each species were pooled (5 individual reactions for each species) and cloned into the pCR 2.1 TOPO vector, transformed into TOP10 Escherichia coli cells using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and plated onto LB agar plates containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Positive clones from each species were randomly selected and sequenced on an ABI 3730 capillary sequencer with ABI BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing chemistry.

2.3 Phylogenetic analysis

Sequences were first checked for chimeras using the online program CHECK-CHIMERA at the Ribosomal Database Project (Cole et al. 2003). Putative chimeric sequences were removed from phylogenetic analyses. Hepatopancreas bacterial sequences were submitted to BLAST searches (Altschul et al. 1997) to find closely related sequences in public databases and grouped by phyla according to the search results. All sequences in the phylum Firmicutes from the clone libraries, and closely related sequences from public databases (including previously published symbiont sequences from other isopod host species, Fraune and Zimmer 2008), were aligned with the NAST algorithm on the greengenes website (DeSantis et al. 2006); the resulting alignment was checked manually. A neighbor-joining tree combining representative sequences of both hosts obtained in this study and sequences from public databases was created with the software MEGA v. 4 (Tamura et al. 2007) with Kimura 2-parameter distances (Kimura 1980) and bootstrapping of 1,000 replicates (Felsenstein 1985). For the maximum likelihood (ML) analysis models of molecular evolution were selected on the basis of MODELTEST (Posada and Crandall 1998) as implemented by FindModel (http://hcv.lanl.gov/content/hcvdb/findmodel/findmodel.html). The ML parameter values were optimized with a BIONJ tree as a starting point in PhyML (Guindon and Gascuel 2003). Support values of nodes on the ML tree were estimated with 500 bootstrap replicates.

2.4 Population screening with Symbiont specific primers

Isopods of Ligia pallasii and Ligia occidentalis were collected at 20 different locations (Table 1) and the hepatopancreas of isopods was dissected as described above. DNA was extracted either with Mo Bio Power Soil® DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad CA) or with a CTAB extraction protocol (Schulenburg et al. 1999). DNA was checked for quality and quantified against a standard of known concentration on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Diagnostic PCRs for the presence of Mycoplasma-like symbionts were performed using the primer pair PsSym372f (5′-CAG CAG TAG GGA ATT TTT CAC-3′) (Wang et al. 2007) and 1492r (5′-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3′) (Weisburg et al. 1991) targeting a portion of approximately 1130 bps of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene.

Each PCR reaction contained: 2.5 µL of 10X reaction buffer, 200 µM of each dNTP, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 pmol of each primer, 0.2 µg/µl BSA, 0.5U Taq polymerase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), 5–10 ng of DNA template, and water to a total reaction volume of 25 µl. The PCR was performed at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 40 s at 52°C, and 50 s at 72°C, with a final extension at 72°C for 3 min. All PCR reactions were run with a positive control (DNA extracted from the hepatopancreas of Porcelio scaber—previously shown to contain Mycoplasma-like symbionts) and negative controls (DNA extracted from periopods of Ligia pallasii and Ligia occidentalis, no DNA). PCR reactions were screened for positive bands on a 1.5% agarose gel. Samples were considered positive for symbionts when they showed a band of the correct size and negative in the absence of such a band. All samples that showed no band in the initial PCR reaction were run at least twice to assure that absence of a band was not due to technical problems. The percentage of individual Ligia positive for the symbiont in each sample location was determined. Initially, all samples independent of outcome were run multiple times to determine reliability of results. A random sub-sample of positive bands was cleaned with ExoSAP-IT® and sequenced in both directions on an ABI 3730 capillary sequencer to confirm the specificity of the primers to mycoplasma-like symbionts. Sequences were checked against known sequences in GenBank.

3 Results

3.1 16SrRNA clone libraries from the hepatopancreas of Ligia pallasii and Ligia occidentalis

Analysis of partial 16S rRNA sequences indicated that bacteria in the hepatopancreas of L. occidentalis and L. pallasii belonged to 3 phyla: Cytophaga-Flavobacteria-Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, and the clone library of L. pallasii also contained an additional representative sequence from Verrucomicrobia and Actinobacteria (Table 2). In both libraries, mycoplasma-like sequences (Firmicutes) were the most abundant sequences with 45 clones out of 47 clones (96%) from the hepatopancreas of L. occidentalis and 45 of 87 clones (52%) from the hepatopancreas of L. pallasii. In the L. pallasii library Bacteroidetes (16 of 87 clones, 18%), Gammaproteobacteria (17 of 87 clones, 20%) and Betaproteobacteria (seven of 87 clones, 8%) had additional representative clones. Clones in the Firmicutes were 98% similar within each host species and were also 98% similar between L. pallasii and L. occidentalis host species. The closest representatives in public databases were symbionts obtained from the hepatopancreas of other isopod species (90 to 91% similarity to clones from the intertidal isopods Tylus europeaus and Ligia oceanica). Sequences were submitted to GenBANK under the Accession numbers GU111260-GU111306 and GU211017-GU211104.

3.2 Phylogenetic tree of mycoplasma like symbionts

Both neighbor-joining and maximum likelihood methods revealed essentially the same tree topology as shown in the neighbor-joining tree in Fig. 2. Bacteria from different individuals in both L. pallasii and L. occidentalis clustered together and were distinct from sequences obtained from other host species. Host specificity could not be confirmed for these two closely related species. Sequences obtained in this study were most closely related to those recovered from the hepatopancreas of other isopods from intertidal habitats (Tylos europeaus and Ligia occidentalis) with strong bootstrap support for this clustering. A cluster of all symbionts from the hepatopancreas of different isopod species was supported by our analysis, whereas Candidatus Bacilloplasma, a Firmicute obtained from the hindgut lining of P. scaber (Kostanjsek et al. 2007) differed from this grouping (Fig. 2).

Neighbor-joining tree shows Mycoplasma-like symbionts of Ligia pallasii and L. occidentalis cluster together with symbionts from other intertidal isopods. All symbiont sequences from the hepatopancreas from isopods (sequences in bold this study, other isopod sequences previously published in Fraune and Zimmer 2008) form a group that is different from bacterial sequences in public databases recovered from other host species. Bootstrap support values are given above branches first values for ML analysis and 2nd value neighbor joining. GenBank accession numbers are given for all sequences

3.3 Symbiont screens

A total of 273 Ligia hosts from 20 stations (165 L. pallasii from 14 stations and 109 L. occidentalis from 10 stations) were screened for the presence of mycoplasma-like symbionts (Table 1); the decision was made to focus on mycoplasma-like symbionts since these were the most abundant symbionts in the clone libraries of both L. pallasii and L. occidentalis. Positive bands were obtained for all populations checked for both host species. The percentage of positive individuals varied between stations from 38% to 100% for L. pallasii and 33% to 100% for L. occidentalis with overall similar prevalence of infection (Fig. 2). No clear evidence for a latitudinal trend in prevalence of infection could be detected for either species. Infection prevalence differed between L. pallasii and L. occidentalis at stations where both species could be collected. BLAST searches confirmed that all randomly sequenced PCR products (submitted to GenBank under accession numbers GU197554-GU197586) were related to symbiont sequences from isopods.

4 Discussion

4.1 Occurrence of symbionts in intertidal Ligia

The present study showed that sequences obtained from the clone libraries of both Ligia pallasii and L. occidentalis contained mycoplasma-like symbionts that were 90–91% similar to those previously described from Tylos europeaus (Tylidae) collected in Italy and Ligia oceanica collected in Germany (Fraune and Zimmer 2008). This cluster was strongly supported by bootstrap values on the phylogentic tree obtained in this study. Three of the host species in this cluster belong to the primitive Ligiidae, but T. europeaus is a member of a different oniscidean family (Schmalfuss 2003). This finding confirms the lack of strict co-evolutionary history between host and symbionts as has been previously discussed (Fraune and Zimmer 2008). Host habitat may play an important role, as all Ligia species as well as T. europeaus occur in intertidal habitats with access to similar food sources (Kensley 1974; Pennings et al. 2000; Laurand and Riera 2006). It appears that the type of preferred substrate within the intertidal habitat (rock for L. pallasii, L. occidentalis, and L. oceanica versus sand for T. europeaus) does not matter. This makes sense, since similar food sources (algal wrack, diatoms and bacteria) are available at both habitats, and isopods are highly mobile and can easily reach preferred food. Mycoplasma-like symbionts appear to be restricted to terrestrial and intertidal isopods and to be lacking in marine isopods, as to date no bacteria were found in the hepatopancreas of two suborders of marine isopods, the Valvifera and Sphaeromatidea (Zimmer et al 2001; Wang et al. 2007). These subtidal isopods tend to feed on fresh macroalgae (Zimmer et al. 2001; Orav-Kotta and Kotta 2004), rather than algal wrack and diatoms.

4.2 Host symbiont specificity

Specificity of host/symbiont interactions appears not to hold true for the congeners L. pallasii and L. occidentalis, since mycoplasma-like symbiont sequences in this study showed 98% similarity both within as well as between the two host species, and sequences from both host species grouped together on the phylogenetic tree. A recent extensive study on the evolution of isopod symbiont associations (Fraune and Zimmer 2008) suggests high levels of specificity between host and symbionts, but only investigated distantly related isopods. The present study shows that L. pallasii and L. occidentalis (belonging to the same genus) show more recent diversification that is not yet reflected in their symbionts.

All mycoplasma-like sequences so far recovered from the hepatopancreas of different isopod species, including sequences obtained in this study, are more closely related to each other than mycoplasma-like bacteria from other non isopod hosts (e.g deep sea shrimp, termites and earthworms). Different areas of the digestive system of one isopod host can have different symbionts: P. scaber has distinctly different mycoplasma-like bacteria in the hepatopancreas (Candidatus Hepatoplasma crinochetorum, Wang et al. 2004a, 2004b) and in the hindgut Candidatus Bacilloplasma (Kostanjsek et al. 2007) as shown in Fig. 2. Different areas within the digestive system, with different functions and environmental conditions, are prone to form strong associations with different bacterial types (Eckburg et al. 2005; Kostanjsek et al. 2007; Gong et al. 2007). The phylogenetic association of bacterial sequences from the hepatopancreas of L. pallasii and L. occidentalis with those from the hepatopancreas of other isopods but not with Candidatus Bacilloplasma (Kostanjsek et al. 2007) from the hindgut supports the notion of strict tissue specificities of mycoplasmas in arthropod hosts (Razin 2006) (Fig. 3).

4.3 Prevalence and transmission of mycoplasma-like symbionts in Ligia

Mycoplasma-like symbionts were found in all populations of both L. pallasii and L. occidentalis screened in this study. This result contradicts the notion that this group of symbionts is absent (Wang et al. 2007) or rare (Fraune and Zimmer 2008) in Ligiidae. Symbiont prevalence, however, varied greatly between locations as was described in previous studies of terrestrial isopods (Wang et al. 2007; Fraune and Zimmer 2008). No clear pattern of variation in infection prevalence along abiotic gradients such as latitude or temperature was found, and further study is necessary to eliminate or identify those ecological factors that influence symbiont occurrence. Associations of facultative symbionts with different hosts have been shown to vary geographically (e.g. Tsuchida et al. 2002; Leonardo and Muiru 2003; Simon et al. 2003), and might confer different benefits under varying environmental stressors such as heat stress (Montllor et al 2002; Berkelmanns and van Oppen 2006) and parasites (Oliver et al. 2003, 2006).

While the specific role of mycoplasma-like symbionts in the hepatopancreas during the digestive process remains unclear, experimental work in P. scaber demonstrated increased survival of individuals with Candidatus Hepatoplasma crinochetorum under prolonged conditions of severe nutrient limitation (Fraune and Zimmer 2008). The correlation between increased survival and presence of facultative symbionts does not rule out that dietary components may influence the types of bacteria present in the digestive systems, as has been shown for humans (Duncan et al. 2007).

Isopods appear to obtain their symbionts from the environment (Wang et al. 2007). It has been suggested that mutualistic symbioses evolve when symbionts are transmitted vertically from parents to offspring (Herre et al. 1999), yet many examples of environmental transmission of mutualistic symbionts exist: for example in corals (van Oppen 2004), chemoautrophic tubeworms (Nussbaumer et al. 2006), the squid Euprymna scolopes (Nyholm et al. 2000), and in hemiptera (Fukatsu and Hosokawa 2002; Kikuchi et al. 2007). In plataspid stink bugs, symbionts are acquired each generation in the nymphal stage (Kikuchi et al. 2007). Ligiidae brood their young in a ventral brood pouch that is open to surrounding environment. Transmission of symbionts from the mother or other species via the environment is possible. Offspring is potentially exposed to symbionts from isopod excretions while the mother is fanning water through the brood pouch with her legs thereby preventing desiccation of her brood. Future work should investigate symbiont prevalence in different life history stages of Ligia. The gregarious lifestyle of Ligia, wherein great numbers of individuals congregate to preserve moisture (Carefoot 1973), could also be a means of exchange of symbionts and lead to stable microbial associations. Additionally, transmission could occur through coprophagy, ingestion of bacteria in feces voided by self or conspecifics (Kautz et al. 2002; Carefoot 1973).

4.4 Microbial diversity in 16S clone libraries

Aside from mycoplasma-like symbionts, other microbes were recovered in the clone libraries of both L. pallasii and L. occidentalis. The role of these microbes is unclear and more work is required to determine their contribution to the host, if any. It is possible that these microbes are transients rather than residents in the hepatopancreas. Host surface sterilization and the use of sterile techniques during dissection makes it unlikely that these bacteria are contaminants.

Methods used in this study do not allow for a distinction between the occurrence of multiple symbionts in one individual, and different bacteria in different individuals for L. occidentalis. The microbial diversity recovered exceeded the number of individuals pooled in the creation of the L. pallasii library, which indicates that more than one symbiont type was present in individual hosts. While two distinct microbial symbionts Candidatus Hepatincola porcellionum (Rickettsiales, a-Proteobacteria; Wang et al. 2004a) and Candidatus Hepatoplasma crinochetorum (Mycoplasmatales, Mollicutes; Wang et al. 2004a, Wang et al. 2004b) have been described in the terrestrial isopod Porcelio scaber, they appear not to co-occur in individuals. An exception to the one host one symbiont rule is the lake isopod Asellus aquaticus (Asellidae) that was found to harbor additional microbes from the Rhodobacter, Burkholderia, Aeromonas or Ricketsiella groups (Wang et al. 2007). While sequences similar to Burkholderia were also found in Ligia pallasii there was no overlap with other microbial species between the two hosts. Sequences in the genus Vibrio were recovered from L. pallasii. Vibrio belong to a diverse mostly marine group of bacteria with a few species known as causing disease in stressed organisms, but some others are known to form mutualistic symbioses (Farmer and Hickman-Brenner 2006). Ecological specialization with spatial and temporal resource partitioning has been shown for this group (Hunt et al. 2008).

The significance of multiple bacterial types in the hepatopancreas is unknown but may be beneficial to the host. Both host individuals and populations could benefit from a diversity of symbionts in the hepatopancreas, as diversity would help to protect organisms against unstable environmental conditions, ensuring the ability of the bacteria and their hosts to resist environmental stress (Naeem and Li 1997) as has been shown for biofilm communities (Boles et al. 2004). Further studies are needed to investigate both the stability of multiple species associations and the effects of additional microbes on the widespread mycoplasma-like symbionts in semi-terrestrial isopods.

5 Conclusion

This study clearly shows that facultative symbionts are frequently encountered in Ligia and are not as rare as previously believed. Mycoplasma-like bacteria that were previously considered to be common only in fully terrestrial isopods have now been shown to be prevalent also in semi-terrestrial high intertidal isopods. Ligia spp. live in the transition zone between marine and terrestrial habitats. In fact all populations of L. pallasii and L. occidentalis tested over a wide geographic range possessed symbionts, making Ligia and their symbionts a good model system for the study of symbiont association during sea-land transitions. Between these two closely related isopod species, which share a broad area of range overlap, no host specificity was discovered. Symbionts from hosts found in intertidal habitats clustered together compared to those from terrestrial hosts. Host habitat in addition to strict host phylogeny appears to influence the phylogenetic relation to symbionts.

References

Abbott DP (1939) Shore Isopods: niches occupied and degrees of transition toward land life with special reference to the family Ligydae. Proc 6th Pac Sc Congress

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402

Berkelmanns R, van Oppen MJH (2006) The role of zooxanthellae in the thermal tolerance of corals: a ‘nugget of hope’ for coral reefs in an era of climate change. Proc Biol Soc B Series: Biol Sci 273:2305–2312

Boles BR, Thoendel M, Singh PK (2004) Self-generated diversity produces “insurance effects” in biofilm communities. PNAS 101:16630–16635

Breznak JA, Brune A (1994) Role of microorganisms in the digestion of lignocellulose by termites. Annu Rev Entomol 39:453–487

Buchner P (1965) Endosymbiosis of animals with plant microorganisms. Interscience Publishers, New York

Buckling A, Rainey FP (2002) The role of parasites in sympatric and allopatric host diversification. Nature 420:496–499

Carefoot TH (1973) Studies of the growth, reproduction and life cycle of the supralittoral isopod Ligia pallasii. Mar Biol 18:302–311

Carefoot TH, Taylor BE (1995) Ligia: a prototypal terrestrial isopod. In: Alikhan MA (ed) Crustacean issues 9: terrestrial isopod biology. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 47–60

Cole JR, Chai B et al (2003) The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): previewing a new autoaligner that allows regular updates and the new prokaryotic taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res 31:442–443

DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N et al (2006) Greengenes, a chimera checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Env Microbiol 72:5069–5072

Dillon RJ, Dillon VM (2004) The gut bacteria of insects: non-pathogenic interactions. Annu Rev Entomol 49:71–92

Doebeli M, Dieckmann U (2000) Evolutionary branching and sympatric speciation caused by different types of ecological interactions. Am Nat 156:S77–S101

Douglas AE (1994) Symbiotic interactions. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Duncan SH, Belenguer A, Holtrop G et al (2007) Reduced dietary intake of carbohydrates by obese subjects results in decreased concentrations of butyrate and butyrate-producing bacteria in feces. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:1073–1078

Eckburg PB, Bik EN, Bernstein CN et al (2005) Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 308:1635–1638

Edney EB (1968) Transition from water to land in isopod crustaceans. Am Zool 8:309–326

Farmer J, Hickman-Brenner F (2006) The Genera Vibrio and Photobacterium. In: Dworkin M (ed) The Prokaryotes, 3rd edn. Springer

Felsenstein J (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783–791

Fraune S, Zimmer M (2008) Host-specificity of environmentally transmitted Mycoplasma-like isopod symbionts. Environ Microbiol 10:2497–2504

Fukatsu T, Hosokawa T (2002) Capsule-transmitted gut symbiotic bacterium of the Japanese common plataspid stinkbug, Megacopta punctatissima. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:389–396

Gong JH, Si WD, Forster RJ et al (2007) 16S rRNA gene-based analysis of mucosa-associated bacterial community and phylogeny in the chicken gastrointestinal tracts: from crops to ceca. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 59:147–157

Guindon S, Gascuel O (2003) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Sys Biol 52:696–704

Hames CAC, Hopkin SP (1989) The structure and function of the digestive system of terrestrial isopods. Zool Lond 217:599–627

Herre EA, Knowlton N, Mueller UG, Rehner SA (1999) The evolution of mutualism: exploring the paths between conflict and cooperation. TREE 14:49–53

Hopkin SP, Martin MH (1982) The distribution of zinc, cadmium, lead and copper within the hepatopancreas of a woodlouse. Tissue Cell 14:703–715

Hunt DE, David LA, Gevers D et al (2008) Resource partitioning and sympatric differentiation among closely related bacterioplankton. Science 320:1081–1085

Kautz G, Zimmer M, Topp W (2002) Does Porcellio scaber (Isopoda: Oniscidea) gain from copraphagy? Soil Biol Biochem 34:1253–1259

Kensley B (1974) Aspects of the biology and ecology of the genus Tylos Latreille. Ann S Afr Mus 65:401–471

Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T (2007) Insect-microbe mutualism without vertical transmission: a stinkbug acquires a beneficial gut symbiont from the environment every generation. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:4308–4316

Kimura M (1980) A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. Molec Evol 16:111–120

Kostanjsek R, Strus J, Avgustin G (2007) “Candidatus Bacilloplasma,” a novel lineage of Mollicutes associated with the hindgut wall of the terrestrial isopod Porcellio scaber (Crustacea: Isopoda). Appl Environ Microbiol 73:5566–5573

Lau WW, Jumars PA, Armbrust EV (2002) Genetic diversity of attached bacteria in the hindgut of the deposit-feeding shrimp Neotrypaea (formerly Callianassa) californiensis (Decapoda: Thalassinidae). Microb Ecol 43:455–466

Laurand S, Riera P (2006) Trophic ecology of the supralittoral rocky shore (Roscoff, France): a dual stable isotope (ä13C, ä15N) and experimental approach. J Sea Res 56:27–38

Leonardo TE, Muiru GT (2003) Faculatative symbionts are associated with host plant specialization in pea aphid populations. Proc R Soc Lond B 270:209–212

Mattern D, Schlegel M (2001) Molecular evolution of the small subunit Ribosomal DNA in Woodlice (Crustacea, Isopoda, Oniscidea) and implications for oniscidean phylogeny. Molec Phyl Evol 18(1):54–65

Montllor CB, Maxmen A et al (2002) Facultative bacterial endosymbionts benefit pea aphids Acyrthosiphon pisum under heat stress. Ecol Entomol 27:189–195

Naeem S, Li SB (1997) Biodiversity enhances ecosystem reliability. Nature 390:507–509

Neimark H, Mitchelmore D, Leach RH (1998) An approach to characterizing uncultivated prokaryotes: the grey lung agent and proposal of a Candidatus taxon for the organism, “Candidatus Mycoplasma ravipulmonis”. Int J Syst Bacteriol 48:389–394

Nussbaumer AD, Fisher CR et al (2006) Horizontal endosymbiont transmission in hydrothermal vent tubeworms. Nature 441:345–348

Nyholm SV, Stabb EV, Ruby EG, McFall-Ngai MJ (2000) Establishment of an animal-bacterial association: recruiting symbiotic vibrios from the environment. PNAS 97:10231–10235

Oliver KM, Russell JA, Moran NA, Hunter MS (2003) Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. PNAS 100:1803–1807

Oliver KM, Moran NA, Hunter MS (2006) Costs and benefits of a superinfection of facultative symbionts in aphids. Proc Royal Soc B-Biol Sciences 273:1273–1280

Orav-Kotta H, Kotta J (2004) Food and habitat choice of the isopod Idotea baltica in the northeastern Baltic Sea. Hydrobiol 514:79–85

Pennings SC, Carefoot TH, Zimmer M et al (2000) Feeding preferences of supralittoral isopods and amphipods. Can J Zool 78:1918–1929

Posada D, Crandall KA (1998) MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14:817–818

Razin S (2006) The genus Mycoplasma and related genera (class Mollicutes). In: Dworkin M (ed) the prokaryotes, 3rd edn. Springer

Schmalfuss H (1978) Ligia simoni: a model for the evolution of terrestrial isopods. Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde Serie A 317:1–5

Schmalfuss H (1989) Phylogenetics in Oniscidea. Monitore zool. ital. (N.S). Monogr 4:3–27

Schmalfuss H (2003) World catalog of terrestrial isopods. Stuttgarter Beitrage zur Naturkunde Serie A (Biology) 654:1–341

Schulenburg JH, English U, Wägele JW (1999) Evolution of ITS1 rDNA in the Digenea (Platyhelminthes: Trematoda): 3′ end sequence conservation and its phylogenetic utility. J Mol Evol 48:2–12

Simon JC, Carre S et al (2003) Host-based divergence in populations of the pea aphid: insights from nuclear markers and the prevalence of facultative symbionts. Proc Royal Soc B-Biol Sciences 270:1703–1712

Sutton SL, Holdich DM (1984) The biology of terrestrial isopods. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London, no. 53, Oxford University Press, New York

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S (2007) MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24:1596–1599

Tsuchida T, Koga R, Shibao H et al (2002) Diversity and geographic distribution of secondary endosymbiotic bacteria in natural populations of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Mol Ecol 11:2123–2135

van Oppen MJH (2004) Mode of zooxanthella transmission does not affect zooxanthella diversity in acroporid corals. Mar Biol 144:1–7

Wang Y, Stingl U, Anton-Erxleben F et al (2004a) “Candidatus hepatoplasma crinochetorum”, a new stalk-forming lineage of Mollicutes colonizing the midgut glands of a terrestrial isopod. Appl Env Microbiol 70:6166–6172

Wang Y, Stingl U, Anton-Erxleben F et al (2004b) ‘Candidatus Hepatincola porcellionum’ gen. nov., sp. nov., a new, stalk-forming lineage of Rickettsiales colonizing the midgut glands of a terrestrial isopod. Arch Microbiol 181:299–304

Wang Y, Brune J, Zimmer M (2007) Bacterial symbionts in the hepatopancreas of isopods: diversity and environmental transmission. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 61:141–152

Weisburg W, Barns S, Pelletier D, Lane D (1991) 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol 173:697–703

Wood S, Griffith BS (1988) Bacteria associated with the hepatopancreas of the woodlice Oniscus asellus and Porcellio scaber (Crustacea, Isopoda). Pedobiologia 31:89–94

Zimmer M (2002) Nutrition in terrestrial isopods (Isopoda: Oniscidea): an evolutionary-ecological approach. Biol Rev 77:455–493

Zimmer M, Topp W (1998) Microorganisms and cellulose digestion in the gut of the woodlouse Porcellio scaber. J Chem Ecol 24:1397–1408

Zimmer M, Danko JP, Pennings SC et al (2001) Hepatopancreatic endosymbionts in coastal isopods (Crustacea: Isopoda), and their contribution to digestion. Mar Biol 138:955–963

Zimmer M, Danko JP, Pennings SC et al (2002) Cellulose digestion and phenol oxidation in coastal isopods (Crustacea: Isopoda). Mar Biol 140:1207–1213

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided through University of California Davis Center for Population Biology Research Grant, Pacific Coast Science and Learning Center Research Grant, Explorer’s Club Diversa Research Fund, University of California Davis Graduate Group in Ecology Fellowship, Bodega Marine Lab Fellowship. Thanks to M. Dethier, E. Kuo, A. Newsom and G. Torres for support with field collections. R. Grosberg and D. Nelson provided valuable input during development of this project. Thanks to M. Baerwald, T. Grosholz, L. Feinstein, D.R. Strong and M. Winder for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Eberl, R. Sea-land transitions in isopods: pattern of symbiont distribution in two species of intertidal isopods Ligia pallasii and Ligia occidentalis in the Eastern Pacific. Symbiosis 51, 107–116 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13199-010-0057-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13199-010-0057-3