Abstract

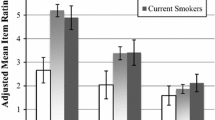

We examined perceived risk, worry, and illness representations of lung cancer by smoking status using data from the 2005 Health Information National Trends Survey (n = 1,765). Perceived lung cancer risk was rated “very high” more frequently by current (15.2%) than former (1.9%) and never (1.6%) smokers. Current smokers more frequently reported worry about lung cancer (18.4%) than former (3.1%) and never smokers (1.8%). Confusion about lung cancer prevention was higher among current (55.2%) than former (41.3%) or never smokers (38.2%). Agreement that lung cancer is caused by a person’s behavior was higher among never (86.1%) and former (82.6%) than current smokers (75.4%). In multivariable models, never (OR = .07) and former smokers (OR = .16) were less likely than current smokers to perceive their lung cancer risk as high. Never smokers (OR = .21) were significantly less likely than current smokers to report worrying about lung cancer, while former and current smokers did not differ.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (2007) Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs—2007. Atlanta, GA, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/tobacco_control_programs/stateandcommunity/best_practices/index.htm. Accessed December 2009

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (2008) Targeting tobacco use: the nation’s leading cause of preventable death at a glance 2008. http://www.cdc.gov/NCCDPHP/publications/aag/osh.htm. Accessed December 2009

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (2004) The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Washington, D.C. For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O., 2004. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/smokingconsequences/. Accessed December 2009

Fiore MC, et al. (2008) Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 Update. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD. Public Health Service. http://www.ahrq.gov/path/tobacco.htm. Accessed December 2009

Cameron LD, Leventhal H (2003) The self-regulation of health and illness behavior. Routledge, New York

Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D (1980) The common sense model of illness danger. In: Rachman S (ed) Medical psychology, vol 2. Pergamon, New York, pp 7–30

Leventhal H, Brissette I, Leventhal EA (2003) The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In: Cameron LD, Leventhal H (eds) The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. Routledge, London, pp 42–65

Hagger MS, Orbell S (2003) A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychol Health 18:141–184. doi:10.1080/088704403100081321

Witte K (1998) Fear as motivator, fear as inhibitor: using the extended parallel process model to explain fear appeal successes and failures. In: Anderson PA, Guerrero LK (eds) Handbook of communication and emotion: research, theory applications, and contexts. Academic Press, New York, pp 423–450

Borkovec TD, Robinson E, Pruzinsky T, Dupree JA (1983) Preliminary exploration of worry: some characteristics and processes. Behav Res Ther 23:481–482, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/00057967. Accessed January 2010

Lerman C, Schwartz MD, Lin TH, Hughes C, Narod S, Lynch HT (1997) The influence of psychological distress on use of genetic testing for cancer risk. J Consult Clin Psychol 65:414–420, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science. Accessed January 2010

McCaul KD, Schroeder DM, Reid PA (1996) Breast cancer worry and screening: some prospective data. Health Psychol 15(6):430–433, http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/hea/15/6/. Accessed January 2010

Mermelstein R, Weeks K, Turner L, Cobb J (1999) When tailored feedback backfires: a skin cancer prevention intervention for adolescents. Canc Res Ther Contr 8:69–79

Schwartz M, Lerman C, Daly M, Audrain J, Masny A, Griffith K (1995) Utilization of ovarian cancer screening by women at increased risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 4(3):269–273, http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/4/3.toc. Accessed January 2010

Miller SM, Shoda Y, Hurley K (1996) Applying cognitive-social theory to health-protective behavior: Breast self-examination in cancer screening. Psychological Bulletin 119:70–94, http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/bul/119/1/. Accessed January 2010

Janz NK, Becker MH (1984) The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q 11(1):1–47. doi:10.1177/109019818401100101

Leventhal H, Cameron L (1987) Behavioral theories and the problem of compliance. Patient Educ Couns 10:117–138. doi:10.1016/0738-3991(87)90093-0

Weinstein ND (2000) Perceived probability, perceived severity, and health-protective behavior. Health Psychol 19(1):65–74. doi:10.KB7//0278-6133.19.1.65

Office of Management and Budget (1997) Revisions to the standards for the classification of federal data on race and ethnicity. Federal Register. 62:58781–58790 ed, 1997. http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/rewrite/fedreg/ombdir15.html. Accessed December 2009

Research Triangle Institute (2004) SUDAAN example manual: release 9.0.Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC

Funding

This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract no. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Declaration of Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Finney Rutten, L.J., Blake, K.D., Hesse, B.W. et al. Illness Representations of Lung Cancer, Lung Cancer Worry, and Perceptions of Risk by Smoking Status. J Canc Educ 26, 747–753 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-011-0247-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-011-0247-6