Abstract

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are a class of medications for management of diabetes and obesity. The objective of this study is to characterize the epidemiology of GLP-1RA cases reported to US poison centers.

Methods

We analyzed cases involving a GLP-1RA reported to the National Poison Data System during 2017–2022.

Results

There were 5,713 single-substance exposure cases reported to US poison centers involving a GLP-1RA. Most cases were among females (71.3%) and attributable to therapeutic errors (79.9%). More than one-fifth (22.4%) of cases were evaluated in a healthcare facility, including 0.9% admitted to a critical care unit and 4.1% admitted to a non-critical care unit. Serious medical outcomes were described in 6.2% of cases, including one fatality. The rate of cases per one million US population increased from 1.16 in 2017 to 3.49 in 2021, followed by a rapid increase of 80.9% to 6.32 in 2022. Trends for rates of serious medical outcomes and admissions to a healthcare facility showed similar patterns with 129.9% and 95.8% increases, respectively, from 2021 to 2022.

Conclusions

Most GLP-1RA cases reported to US poison centers were associated with no or minimal effects and did not require referral for medical treatment; however, a notable minority of individuals experienced a serious medical outcome or healthcare facility admission. The rate of reported cases increased during the study period, including an 80.9% increase from 2021 to 2022. Opportunities exist to improve provider and patient awareness of the adverse effects of these medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are a class of medications commonly used in the treatment of type II diabetes mellitus and, more recently, obesity [1, 2]. Although only three GLP-1RAs — Saxenda (liraglutide), Wegovy (semaglutide), and Zepbound (tirzepatide, which is also a glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor agonist) — are approved in the United States (US) for chronic weight management in adults by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [3,4,5], the medication class has become a popular off-label option for weight loss [6]. Provider awareness combined with intense public interest has precipitated high levels of prescribing and subsequent drug shortages [7]. Evidence that the use of GLP-1RAs improves outcome for heart failure and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis has been published, which could further increase off-label usage [8, 9]. Globally valued at $22.4 billion in 2022, the market size of GLP-1RA medications is expected to demonstrate an annual growth rate of approximately 9.6% through 2032 [10].

GLP-1RAs demonstrate substantial homology with endogenous GLP-1 but have been structurally modified to resist rapid degradation by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 [1, 11]. These modifications vary slightly among drugs in this class, but generally result in enhanced binding to albumin, which slows renal elimination of the drug [11]. Thus, GLP-1RAs are slowly degraded, have relatively long half-lives, and can exert an array of potent effects, including increased satiety, enhanced insulin secretion, and suppression of glucagon [2, 11, 12]. Although these physiologic effects are leveraged for glucose control, beta-cell rehabilitation, and weight loss, adverse effects can also occur. Gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation, are consistently described in clinical trials, systematic reviews, and case reports [13,14,15,16,17,18]. GLP-1RA use has also been associated with cases of pancreatitis, biliary disease, gastroparesis, bowel obstruction, and hypersensitivity reactions [14, 19,20,21,22,23].

Most of the adverse effects related to GLP-1RAs are described in clinical trial settings [13, 15, 16]. With the increased prescribing of this medication class for both on- and off-label indications, continued population-level studies on adverse effects related to these medications are critical. US poison center (PC) data provide a unique opportunity to complement post-marketing drug surveillance data to describe potential adverse events related to GLP-1RA use. In this study, we characterize GLP-1RA cases reported to US PCs using data from the National Poison Data System (NPDS).

Methods

Data Sources

We obtained data from the NPDS, a surveillance system maintained by America’s Poison Centers [24]. The NPDS captures information from contacts by the public and healthcare professionals to regional PCs that serve the entire US and all US territories. Trained Specialists in Poison Information who staff the 24-hour Poison Help Line record information in the NPDS as part of the routine triage and management of these cases. The NPDS employs quality control measures to promote the integrity and completeness of its data [24,25,26]. July 1st intercensal and postcensal population estimates were obtained from the US Census Bureau to calculate annual case rates [27, 28]. This study was determined to be exempt from review by the institutional review board at the authors’ institution.

Case Selection Criteria

Single-substance cases involving a GLP-1RA reported to US PCs between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2022 were identified based on NPDS generic and product codes. Cases were excluded if the medical outcome was documented as a “confirmed non-exposure” (n = 246 cases) or “unrelated effect” (n = 24 cases), which left 5,713 cases for analysis.

Study Variables

We grouped age into the following categories: 1) < 20 years (children/teenagers), 2) 20–49 years (adults), 3) 50–59 years (middle-aged adults), 4) 60–69 years (older adults #1), 5) > 69 years (older adults #2), and 6) unknown. Based on NPDS categories, the level of health care received was classified as: (1) no healthcare facility (HCF) treatment received, (2) treated/evaluated and released, (3) admitted to a critical care unit, (4) admitted to a non-critical care unit, (5) patient refused referral/did not arrive at a HCF, or (6) patient lost to follow-up/left against medical advice. In this study, “patients lost to follow-up/left against medical advice” were treated as “unknown” in analyses. Based on NPDS product codes, substances were categorized into three groups: (1) semaglutide, (2) liraglutide, and (3) other GLP-1RAs. Semaglutide and liraglutide were grouped separately from other GLP-1RAs because, at the time of the study, they were the only two with a FDA-approved indication for chronic weight management (tirzepatide was not approved for this purpose until November 2023) [3, 4].

Medical outcomes, as defined by the NPDS [26], were classified as follows: (1) no effect, (2) minor effect (minimal symptoms that generally resolve rapidly), (3) moderate effect (more pronounced, prolonged, or systemic symptoms than minor effect), (4) major effect (symptoms that are life-threatening or result in substantial disability or disfigurement), (5) death, (6) not followed (minimal clinical effects possible), or (7) unable to follow (judged as potentially toxic exposure). Cases that were “unable to follow (judged as potential toxic exposure)” were treated as “unknown” in analyses. In this study, the category “serious medical outcome” combined the outcomes reported as a moderate effect, major effect, or death. Additional variables examined included sex, year, exposure type (single-substance or poly-substance), reason for exposure, therapeutic error scenario, and related clinical effects.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 28.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics and rates were reported. Odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to determine the magnitude of association between product category and HCF admission and between product category and serious medical outcome.

Results

General Characteristics

Among the 5,713 cases reported to US PCs involving a GLP-1RA as single substance, 71.3% involved females and 98.4% occurred at home (Table 1). Although some cases had more than one route of exposure, 76.3% of cases were associated with injection, and 17.0% with ingestion. Age distribution was individuals < 20 years old (5.8%), 20–49 years old (29.3%), 50–59 years old (27.0%), 60–69 years old (23.8%), and > 69 years old (14.0%).

Most (79.9%) reported cases were associated with therapeutic errors, while 3.8% were intentional in nature. Among the 4,551 cases associated with a therapeutic error, the most common scenario was “inadvertently took/given medication twice” (29.8%), followed by “other incorrect dose” (21.9%) and “medication doses taken/given too close together” (17.7%). Among the 219 intentional cases, 41.6% were coded as “intentional - suspected suicides” and 52.5% were attributed to misuse/abuse. Most “intentional - suspected suicides” were among the 20-49-year-old age group (52.7%), followed by < 20 years old (15.4%,) and 50-59-year-olds (13.2%). Most misuse/abuse cases were among 20-49-year-olds (45.2%), followed by individuals 50–59 years old (20.9%) and 60–69 years old (13.0%).

Highest Level of Health Care Received and Medical Outcomes

Most cases were not referred to a HCF for treatment (74.9%) or refused referral/did not arrive at a HCF (2.7%) (Table 1). Of the 22.4% (n = 1,209) of cases evaluated in a HCF, 17.1% were treated/evaluated and released, 0.9% admitted to a critical care unit, 4.1% admitted to a non-critical care unit, and 0.4% admitted to a psychiatric facility.

More than half (55.8%) of cases were not followed because they were judged to have a non-toxic exposure or a possibility of minimal clinical effects. An additional 20.5% had no effects and 17.4% had minor effects. Serious medical outcomes were identified in 6.2% of cases, including 17 cases (0.3%) with major effects. There was one fatality of a 39-year-old female reported to the NPDS involving a GLP-1RA in the “other GLP-1RA” category. It was coded as a single-substance unintentional adverse drug reaction. Case notes describe the patient presenting for care after developing acute onset of abdominal pain and distension in the setting of constipation. Imaging and exploratory laparotomy were performed and revealed colonic distension, fecal impaction, and proctocolitis with subsequent bowel ischemia. The fatality occurred following multiple operations and a multi-day critical care course complicated by bowel ischemia and resection, suspected gastrointestinal bleeding, and 2 episodes of cardiac arrest (the latter with failure to achieve return of spontaneous circulation). The case was reported to the FDA MedWatch system as a possible adverse event related to the GLP-1RA.

Product Category

The most common product category was semaglutide (42.5%), followed by other types of GLP-1RAs (34.1%) and liraglutide (23.5%) (Table 2). Among semaglutide cases reported to US PCs, 5.6% were admitted to a HCF, compared with 4.7% for liraglutide and 5.5% for the other GLP-1RAs combined. In addition, 7.7% of semaglutide cases were associated with serious medical outcomes compared with 4.7% for liraglutide cases and 5.6% for the other GLP-1RA cases combined. Compared with all non-semaglutide-related cases combined, semaglutide cases did not have significantly different odds of admission to a HCF (OR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.82–1.32) but did have significantly greater odds of a serious medical outcome (OR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.17–1.81).

Related Clinical Effects

The most commonly reported related clinical effects included nausea (17.4%, n = 993), vomiting (13.9%, n = 791), diarrhea (3.4%, n = 192), and abdominal pain (3.3%, n = 190) (Table 3). Among cases admitted to a critical care unit or non-critical care unit, the most common related clinical effects were nausea (34.5%, n = 92), vomiting (30.7%, n = 82), hypoglycemia (22.1%, n = 59), abdominal pain (9.7%, n = 26), and dizziness/vertigo (7.1%, n = 19), and additional selected related clinical effects included increased creatinine (1.9%, n = 5), pancreatitis (0.4%, n = 1), AST, ALT > 1,000 (0.4%, n = 1), renal failure (0.4%, n = 1), and ileus (0.4%, n = 1).

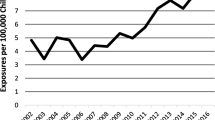

Trend Analysis

The rate of cases per one million US population increased from 1.16 in 2017 to 3.49 in 2021 and then rapidly increased by 80.9% to 6.32 in 2022. The increasing trend was observed across all age groups and both sexes; however, the rapid increase from 2021 to 2022 was not observed among < 20-year-olds, > 69-year-olds (Fig. 1), or males (Appendix 1). When product categories were examined separately, the rate per one million US population for semaglutide increased from 0.13 in 2018 to 1.65 in 2021 (no cases involving semaglutide were reported in 2017) and then rapidly increased by 139.8% to 3.96 in 2022. The rate for “other GLP-1RAs” showed a consistent increase from 0.54 in 2017 to 1.58 in 2022, while the rate for liraglutide remained relatively constant throughout the study period (Fig. 2).

The rate of serious medical outcomes per one million US population increased from 0.07 in 2017 to 0.20 in 2021 and then rapidly increased by 129.9% to 0.45 in 2022 (Fig. 3). The upward trend was observed in all age groups and was primarily driven by increases in rates among 20-49-year-olds, 50-59-year-olds, and 60-69-year-olds (Appendix 2). When product categories were examined separately, the rate of serious medical outcomes for semaglutide increased from 0.01 in 2018 to 0.11 in 2021 and then by 162.2% to 0.30 in 2022; the rate of serious medical outcomes remained relatively constant for liraglutide and “other GLP-1RAs” (Fig. 3).

The rate of admission to a HCF per one million US population increased from 0.07 in 2017 to 0.17 in 2021 and then rapidly increased by 95.8% to 0.34 in 2022 (Fig. 4). The upward trend in the rate was observed among 50-59-year-olds and 60-69-year-olds, and the trend among 20-49-year-olds remained relatively constant from 2017 to 2021 and then rapidly increased from 2021 to 2022 (Appendix 3). When product categories were examined separately, the rate of admission to a HCF for semaglutide increased from 0.01 in 2018 to 0.09 in 2021 and then by 129.1% to 0.21 in 2022, while the admission rate for liraglutide and “other GLP-1RAs” remained relatively constant throughout the study period (Fig. 4).

Discussion

In this investigation of six years of GLP-1RA cases reported to US PCs, most cases were associated with no or minimal effects and most did not require referral for medical treatment in a HCF. However, there were a notable proportion of cases that experienced serious medical outcomes (6.2%) or were admitted to a critical care unit or non-critical care unit (5.0%). Over the study period, the overall rates of GLP-1RA-related cases, and those for serious medical outcomes and admissions to a healthcare facility, increased. When examining specific product groups, semaglutide demonstrated greater accelerations in these rates over time than liraglutide and other GLP-1RAs, especially during the latter part of the study period. These increasing rates are likely reflective of the surge in GLP-1RA prescribing by clinicians in response to a combination of demonstrated clinical efficacy for management of diabetes and obesity [13, 16] as well as intense public interest. The larger increases in rates observed with semaglutide may be attributable to higher prescribing rates associated with the medication’s popularity [6], additional available formulations [29], and studies demonstrating clinical efficacy [30].

Although clinical trials have demonstrated the safety and tolerability of GLP-1RAs, side effects, especially gastrointestinal-related, are known to affect up to 10–40% of users [13, 15]. The most common related clinical effects reported for cases in our study were consistent with previous reports in the literature for this medication class [13,14,15, 17]. Adverse effects are more common during the early phase of treatment, when doses are initiated or increased [15, 31]. Adverse effects from GLP-1RAs can be mitigated through pausing up-titration or dose reduction [15, 32]. For patients experiencing profound side effects, medication discontinuation often leads to symptom abatement. Thus, most GLP-1RA side effects, especially gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, can be managed successfully in the outpatient setting. Both providers and patients should be cognizant that serious side effects can occur and that even desirable effects of GLP-1RAs, such as early satiety, must be monitored closely, because they may affect nutrition or hydration status. In fact, a recent scientific abstract described a case of life-threatening starvation ketoacidosis preceded by 5 days of nausea and vomiting that developed several weeks after starting tirzepatide for weight loss [33]. Patients should be educated to recognize side effects so clinicians can address these promptly to prevent the development of complications. In addition, patients should be educated about the prevention of therapeutic errors, which accounted for more than three-fourths of reported cases. Dosing schedule systems and reminders may help prevent common scenarios, such as taking/giving the medication twice or too close together. Although reported for < 5% of cases in this study, providers should also be aware of the potential for patients to intentionally misuse/abuse GLP-1 agonists or use them for self-harm. This may be more common in populations with mental health or eating disorders, and screening for these conditions should be part of a clinician’s approach when considering this class of medications.

Certain adverse effects associated with GLP-1RAs, such as biliary disease [34, 35], acute kidney injury [36, 37], gastroparesis, or bowel obstruction [21] are more likely to require escalation of care. Additionally, pancreatitis is listed as a possible side effect on prescribing information of GLP-1RAs [38, 39], though this risk has not been clearly described in clinical trials [15, 40]. In our study, we identified only one case with elevated AST, ALT > 1,000 (which could represent hepatobiliary disease), one case with pancreatitis, one case with ileus, and a small number of cases with elevated creatinine (5 cases), including one case with kidney failure. Ongoing post-marketing surveillance and additional studies are needed to further elucidate associations between GLP-1RA use and specific serious, long-term, or delayed adverse effects. Reporting side effects to the FDA MedWatch program is one way providers and patients can help facilitate ongoing surveillance efforts.

Based on case review, the fatality reported in the NPDS appears to be consistent with complications of stercoral colitis, a rare condition that occurs when constipation and fecal impaction progresses to colonic distension and inflammation. In stercoral colitis, dehydrated fecal matter (i.e., fecalomas) can apply pressure to the bowel wall mucosa, causing ulceration, ischemia, necrosis, or perforation [41, 42]. Prompt recognition and management are critical to avoid morbidity and mortality [41, 43]. To our knowledge, this condition has not been previously described in the literature as being associated with GLP-1RA use. Although most cases of GLP-1RA-associated constipation do not progress to stercoral colitis, providers should be aware of the potential risk of this condition.

The high demand for GLP-1RAs has precipitated international drug shortages [7, 44]. Consequently, some patients have turned to compounding pharmacies, which advertise compounded versions of the peptides, for easier and cheaper access to these medications. In the spring of 2023, the FDA issued a warning on compounded semaglutide, citing a lack of FDA approval, reports of adverse effects, and an unknown safety profile [45]. Concurrently, the Obesity Medicine Association issued a position statement reiterating the importance of a transparent drug supply with appropriate regulatory oversight [46]; in its concluding statements, the Obesity Medicine Association recommended that prescribers and patients avoid “compounded polypeptides from undisclosed sources” and that patients should be informed of “potential limitations of compounded peptides” [46, 47]. Further study and regulatory oversight are needed to ensure the safety and efficacy of the compounded peptide drug supply. In addition to concerns about the contents of compounded products and their safety, use of compounded semaglutide may place patients at greater risk of therapeutic errors. These products are offered in multidose vials, unlike the single-dose pen version of the FDA-approved product. Confusion about how to draw up the medication for self-injection and confusion about units (milliliters vs. milligrams vs. units) could lead to large — up to 10- or 20-fold — overdose of these products [48].

Study Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Because the NPDS documents voluntary, self-reported exposures, the PCs and America’s Poison Centers cannot completely verify the accuracy of the information. Not all GLP-1RA cases are reported to PCs; therefore, this study underestimates the number of these cases. Reporting bias may occur, for example, more serious cases may be more likely to be reported than milder ones. Exposure calls to PCs do not necessarily represent a true poisoning or overdose. Due to limitations in NPDS coding, we were unable to separate cases associated with compounded peptides versus FDA-approved medications. Additionally, the indication for which the individual was using a GLP-1RA (e.g., obesity, diabetes) cannot be determined from our data. The relationship of medication dose with related clinical effects, HCF admission, or medical outcome was not examined in this study. Data miscoding by PC personnel or product misidentification by callers may also affect the data presented. Analyses were limited to variables in the NPDS database and individual case notes were only obtained for the fatality in this study. Despite these limitations, the NPDS is a comprehensive, standardized national database commonly used for epidemiologic investigations of poisonings.

Conclusions

Most cases involving a GLP-1RA reported to US PCs were associated with no or minimal effects and most did not require referral for medical treatment in a HCF. However, a notable minority of individuals experienced serious medical outcomes or admission to a healthcare facility. The rate of cases reported to US PCs increased during the study period, including an 80.9% increase from 2021 to 2022; in addition, serious medical outcomes and HCF admissions demonstrated similar large increases of 129.9% and 95.8%, respectively, from 2021 to 2022. These findings likely reflect increased prescribing by health care providers and the growing popularity of GLP-1RAs among the public. Opportunities exist to improve provider and patient education. Clinicians and patients should be aware of both the common and rare adverse effects of this medication class, so that side effects can be addressed promptly to prevent symptom progression and complications. Education about prevention strategies for common types of therapeutic errors is also important. The effects of long-term use of GLP-1RAs, especially those more recently introduced into the market, have not been completely elucidated and are an important area of future study because this class of medications is likely to be used by an increasingly greater population as they are studied for additional indications.

Data Availability

Data analyzed in this study were from the National Poison Data System, which is owned and managed by America’s Poison Centers. Data requests should be submitted to America’s Poison Centers.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FDA:

-

United States Food and Drug Administration

- GLP-1RA:

-

glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist

- HCF:

-

Healthcare facility

- NPDS:

-

National Poison Data System

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PC:

-

Poison Center

- US:

-

United States

References

Collins L, Costello R. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551568/.

Cornell S. A review of GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes: a focus on the mechanism of action of once-weekly agents. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45(S1):17–27.

Food US, Administration D. FDA approves weight management drug for patients aged 12 and older. 2021. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-weight-management-drug-patients-aged-12-and-older. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Food US, Administration D. FDA approves new drug treatment for chronic weight management, first since 2014. 2021. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-treatment-chronic-weight-management-first-2014. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Food US, Administration D. FDA approves new medication for chronic weight management. 2023. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-medication-chronic-weight-management. Accessed January 26, 2024.

Blum D. What is Ozempic and why is it getting so much attention? The New York Times; 2022. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/22/well/ozempic-diabetes-weight-loss.html. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Whitley HP, Trujillo JM, Neumiller JJ. Special Report: potential strategies for addressing GLP-1 and dual GLP-1/GIP receptor ggonist shortages. Clin Diabetes. 2023;41(3):467–73.

Kosiborod MN, Abildstrom SZ, Borlaug BA, et al. Semaglutide in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(12):1069–84.

Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of subcutaneous semaglutide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(12):1113–24.

Global Market Insights. GLP-1 receptor agonist market - by drug class (semaglutide, dulaglutide, liraglutide, exenatide), by route of administration (parenteral), by application (type 2 diabetes, obesity), by distribution (hospital, retail), global forecast, 2023–2032. 2023 Available from: https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/glp-1-receptor-agonist-market. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Andersen A, Lund A, Knop FK, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(7):390–403.

Drucker DJ. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):740–56.

Shyangdan DS, Royle P, Clar C et al. Glucagon-like peptide analogues for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):CD006423.

Smits MM, Van Raalte DH. Safety of semaglutide. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:645563.

Trujillo J. Safety and tolerability of once-weekly GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45(Suppl 1):43–60.

Vilsbøll T, Christensen M, Junker AE, et al. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on weight loss: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344:d7771.

Zheng SL, Roddick AJ, Aghar-Jaffar R, et al. Association between use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists, and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors with all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1580–91.

Rotella JA, Wong A. Liraglutide toxicity presenting to the emergency department: a case report and literature review. Emerg Med Australasia. 2019;31(5):895–6.

He L, Wang J, Ping F, et al. Association of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist use with risk of gallbladder and biliary diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(5):513–9.

Pradhan R, Montastruc F, Rousseau V, et al. Exendin-based glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and anaphylactic reactions: a pharmacovigilance analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(1):13–4.

Sodhi M, Rezaeianzadeh R, Kezouh A, et al. Risk of gastrointestinal adverse events associated with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists for weight loss. JAMA. 2023;330(18):1795–7.

Food US, Administration D. Questions and answers - safety requirements for Victoza (liraglutide). 2016 Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/questions-and-answers-safety-requirements-victoza-liraglutide. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Woronow D, Chamberlain C, Niak A, et al. Acute cholecystitis associated with the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists reported to the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(10):1104–6.

America’s Poison Centers. National Poison Data System. 2023 Available from: https://www.aapcc.org/national-poison-data-system. Accessed September 12, 2023.

Wolkin AF, Martin CA, Law RK, et al. Using poison center data for national public health surveillance for chemical and poison exposure and associated illness. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(1):56–61.

Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC et al. 2022 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System (NPDS) from America’s Poison Centers: 40th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol. 2023;61(10):717–939.

U.S. Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population by single year of age and sex for the United States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2020. 2021 Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/technical-documentation/research/evaluation-estimates/2020-evaluation-estimates/2010s-national-detail.html. Accessed October 12, 2023.

U.S. Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population by single year of age and sex for the United States: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022. 2023 Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-national-detail.html. Accessed October 12, 2023.

WebMD LLC. Semaglutide (Rx). 2023 Available from: https://reference.medscape.com/drug/ozempic-rybelsus-wegovy-semaglutide-1000174. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Andreadis P, Karagiannis T, Malandris K, et al. Semaglutide for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(9):2255–63.

Sun F, Chai S, Yu K, et al. Gastrointestinal adverse events of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(1):35–42.

Fineman MS, Shen LZ, Taylor K, et al. Effectiveness of progressive dose-escalation of exenatide (exendin-4) in reducing dose-limiting side effects in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2004;20(5):411–7.

Mercer J, Lipscomb J, Lipscomb J et al. Tirzepatide-induced starvation ketoacidosis: a case report [abstract]. Clin Toxicol. 2023:1–2.

Monami M, Nreu B, Scatena A, et al. Safety issues with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer and cholelithiasis): data from randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(9):1233–41.

Pizzimenti V, Giandalia A, Cucinotta D, et al. Incretin-based therapy and acute cholecystitis: a review of case reports and EudraVigilance spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting database. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(2):116–8.

Kaakeh Y, Kanjee S, Boone K, et al. Liraglutide-induced acute kidney injury. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(1):e7–11.

Leehey DJ, Rahman MA, Borys E, et al. Acute kidney injury associated with semaglutide. Kidney Med. 2021;3(2):282–5.

Novo Nordisk AS. Ozempic (semaglutide), prescribing information. 2020 Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/209637s003lbl.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Novo Nordisk AS. Victoza (liraglutide), prescribing information. 2023 Available from: https://www.novo-pi.com/victoza.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Giorda CB, Sacerdote C, Nada E, et al. Incretin-based therapies and acute pancreatitis risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Endocrine. 2015;48(2):461–71.

Keim AA, Campbell RL, Mullan AF, et al. Stercoral colitis in the emergency department: a retrospective review of presentation, management, and outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;82(1):37–46.

Morano C, Sharman T. Stercoral colitis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560608/.

Ahmad H, Jannat H, Khan U, et al. Stercoral colitis: a diagnostic challenge and therapeutic approach in an elderly patient with chronic constipation. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e39179.

National Health Service. GLP-1 receptor agonists used in the management of type 2 diabetes. 2023 Available from: https://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/publications/MSAN(2023)12.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Food US, Administration D. Medications containing semaglutide marketed for type 2 diabetes or weight loss. 2023 Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/medications-containing-semaglutide-marketed-type-2-diabetes-or-weight-loss. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Obesity Medicine Association. Obesity Medicine Association issues a position statement on compounded peptides. 2023 Available from: https://obesitymedicine.org/obesity-medicine-association-issues-a-position-statement-on-compounded-peptides/. Accessed October 12, 2023.

Fitch A, Auriemma A, Bays HE. Compounded peptides: an Obesity Medicine Association position statement. Obes Pillars. 2023;6:100061.

Couch D, Yemets M, Leonard J. Compounded semaglutide products may compound the risk of therapeutic errors (abstract). Clin Toxicol. 2023;61 (Suppl. 2).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Author, CAK, received a student scholar research stipend from the Child Injury Prevention Alliance while she worked on this study. The interpretations and conclusions in this article do not necessarily represent those of the funding organization. The funding organization was not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Christopher Gaw and Cydney Kemp contributed to the conception and design of the study, conducted data analyses and contributed to interpretation of data; they drafted the article, approved the final version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Hannah Hays contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and interpretation of data; she reviewed and revised the article critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Sandhya Kistamgari conducted data analyses and contributed to interpretation of data; she reviewed and revised the article critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Henry Spiller, Natalie Rine, Allison Rhodes, and Motao Zhu contributed to the interpretation of data; they reviewed and revised the article critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Gary Smith contributed to the conception and design of the study and interpretation of data; he assisted in drafting the article and reviewed and revised the article critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Previous Presentation of Data

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Supervising Editor: Eric J Lavonas, MD, MS.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1:

Appendix 1. Rate of cases involving GLP-1 receptor agonists per one million US population reported to the NPDS by sex, 2017–2022. Appendix 2. Rate of serious medical outcomes involving GLP-1 receptor agonists per one million US population reported to the NPDS by age group, 2017–2022. Appendix 3. Rate of admission to a health care facility involving GLP-1 receptor agonists per one million US population reported to the NPDS by age group, 2017–2022

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaw, C.E., Hays, H.L., Kemp, C.A. et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Cases Reported to United States Poison Centers, 2017–2022. J. Med. Toxicol. 20, 193–204 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-024-00999-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-024-00999-x