Abstract

Introduction

This study investigated the characteristics and compared the trends of pediatric suspected suicide and nonfatal suicide attempts reported to United States (US) poison control centers (PCCs) before and during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

An interrupted time series analysis using an ARIMA model was conducted to evaluate the trends of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–19 years old reported to the National Poison Data System during March 2020 through February 2021 (pandemic period) compared with March 2017 through February 2020 (pre-pandemic period).

Results

The annual number of cases of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts increased by 4.5% (6095/136,194) among children 6–19 years old during March 2020 through February 2021 compared with the average annual number during the previous three pre-pandemic years. There were 11,876 fewer cases than expected from March 2020 to February 2021, attributable to a decrease in cases during the initial three pandemic months. The average monthly and average daily number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–12 years old and 13–19 years old was higher during school months than non-school months and weekdays than weekends during both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods.

Conclusions

There was a greater than expected decrease in the number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–19 years old reported to US PCCs during the early pandemic months, followed by an increase in cases. Recognizing these patterns can help guide an appropriate public health response to similar future crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

By March 2020, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were strongly felt across the United States (US) and a national emergency was announced on March 13 [1]. As schools and businesses closed, large numbers of individuals were confined to their homes. It is important to understand the effects of the pandemic and associated control measures on the health of the population, including suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among US youth. Suicide is among the leading causes of death among US youth, and poisoning is a common method of intentional self-harm in this age group [2]. Previous studies have examined suicide trends during the pandemic in the US and other countries [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. However, these previous studies had limitations, including short pandemic study periods of less than 1 year [6, 9], not national in scope [4, 12], did not focus on the pediatric age group [5, 6, 9, 11, 12], did not specifically compare pre-pandemic and pandemic periods [7, 8], did not evaluate monthly trends [5, 7, 8], examined only emergency department visits [10] or pediatric intensive care unit admissions [3], or lacked more sophisticated analyses such as interrupted time series analysis [4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12]. None of these studies provided a comprehensive comparison of poison-related suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among US children and adolescents.

Our previous study that examined COVID-19 pandemic-related trends of pediatric poison exposures reported to US poison control centers (PCCs) included individuals < 20 years old with an emphasis on exposures related to exploratory behaviors among children < 6 years old [13]. The focus of the current study is different. The objective of this study was to investigate the characteristics and compare the trends of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–19 years old reported to US PCCs during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 1, 2020, through February 28, 2021) compared with pre-pandemic years (March 1, 2017, through February 29, 2020). An interrupted time series analysis using an ARIMA (autoregressive integrated moving average) model was employed in this study.

Methods

Data Source and Case Selection Criteria

The National Poison Data System (NPDS) database, which is managed by America’s Poison Centers (formerly known as the American Association of Poison Control Centers), includes data about cases reported to regional PCCs in the US. PCCs used near real-time processing to upload data to the NPDS, and data were classified by PCC poison specialists based on the reported information. Cases involving children 6–19 years old reported to PCCs from March 1, 2017, to February 28, 2021, were included in the study if the reason for exposure was “intentional-suspected suicide,” which is defined by the NPDS as “an exposure resulting from the inappropriate use of a substance for self-harm or for self-destructive or manipulative reasons” [14]. The outcome of these exposures can be fatal or nonfatal. For purposes of this study, the “2017 year” included March 2017 through February 2018; similar time periods applied to years 2018, 2019, and 2020. Cases were excluded if they occurred in other than the 50 US states or District of Columbia (n = 2055) or had a medical outcome coded as “confirmed non-exposure” or “unrelated effect, the exposure was probably not responsible for the effect(s)” (n = 7707). The terms “case” and “exposure” were used interchangeably in this article. This study was deemed non-human subjects research and exempt from approval by the institutional review board at the authors’ institution.

Study Variables

Variables included in this study were age, sex, date of exposure, exposure site, management site, highest level of health care received, and medical outcome. Age was grouped as 6–12 and 13–19 years old. Exposure site was categorized as (1) residence (own or other), (2) school, (3) other, and (4) unknown. The highest level of health care received was categorized as (1) no health care facility (HCF) care received, (2) treated/evaluated and released, (3) admitted to a HCF (including to a critical care unit [CCU], non-CCU, or psychiatric facility), (4) refused referral/did not arrive at HCF, and (5) unknown (including left against medical advice and lost to follow-up). Medical outcome was categorized as (1) no effect, (2) minor effect, (3) moderate effect, (4) major effect, (5) death, and (6) unknown (including not followed [minimal clinical effects possible], not followed [judged as a non-toxic exposure], or unable to follow [judged as potentially toxic exposure]). Major effect is defined by the NPDS as symptoms which are life-threatening or result in significant residual disability or disfigurement; moderate effect is defined as symptoms which are more pronounced, more prolonged, or more of a systemic nature than minor symptoms; and minor effect is defined as symptoms that usually resolve rapidly without residual disability or disfigurement [14]. During analyses, the moderate effect, major effect, and death categories were combined into a “serious medical outcome” category.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Average values for the 3 years of pre-pandemic data were used in comparisons between pre-pandemic (March 2017 through February 2020) and pandemic (March 2020 through February 2021) periods. US census data for 2020 and 2021 were unavailable at the time of analysis, so rates were not calculated. Proportions were calculated using the total number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts for the respective category as the denominator. An interrupted time series analysis using an ARIMA model was conducted to evaluate the association of the pandemic with suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–19 years old reported to US PCCs. The first ARIMA model provided estimates for the observed (1) step change (level shift), which is an immediate, sustained change following the onset of the pandemic, and (2) ramp, which is the immediate change in the slope after pandemic onset. The 95% CIs for step change and ramp estimates were calculate based on the point estimates with their respective standard error provided by the ARIMA model (95% CI = point estimate ± 1.96 × standard error). A second ARIMA model provided estimates for the predicted number of cases in the absence of the pandemic with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). One of the primary assumptions for ARIMA models is stationarity of time series (i.e., data should have constant means, constant variance, and constant covariance), which was achieved by taking first order differencing for intentional-suspected suicide exposures. First-order differencing means that the outcome at each time point is replaced by the difference between the outcome at that point and outcome at the previous time point, i.e., Y′t = (Yt -Yt-1). Suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts showed a seasonality with higher frequencies reported during school months (September to May) than during non-school months (June to August). This seasonality was managed by taking seasonal differencing at lag 12 using the same procedure as described above except that the difference is taken at each time point and its 12th previous observation, i.e., Y′t = (Yt -Yt-12). Although previous studies have identified an increase in suspected suicides among adolescents reported to US PCCs since 2000 [15, 16], using simple linear regression, there were no statistically significant trends for suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts during 2017–2019, and therefore, a directional component of trend was not included in ARIMA modeling. The overall difference between observed and expected exposures was calculated by summing the difference between observed and expected exposures between March 2020 and February 2021 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference in exposures was calculated using the Poisson distribution [17]. Other analyses included the chi-square test of association. The level of statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

General Characteristics of the Study Population

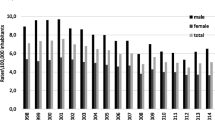

From March 1, 2017, to February 28, 2021, there were 550,865 cases of suspected suicide and nonfatal suicide attempts (average annual pre-pandemic = 136,194; pandemic year = 142,289) managed by US PCCs involving youth 6–19 years old, which represented a 4.5% increase in the annual number of cases from the pre-pandemic (average annual) to the COVID-19 pandemic periods (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Most (94.1%) cases involved children 13–19 years old, peaking at ages 15–16 years during both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods with an observed shift in the age distribution toward younger age during the pandemic period (Fig. 2). Females accounted for 77.6% of cases (Table 1).

Exposure Site and Management Site

Most suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts occurred at the individual’s or another person’s residence (97.9%); this increased from 97.7% (n = 130,076) pre-pandemic to 98.4% (n = 137,341) during the pandemic period (p < 0.001). Suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts at school decreased from an average of 1219 cases per year (0.9% of exposures) during the pre-pandemic period to 377 (0.3% of exposures) during the pandemic period (p < 0.001). Most (88.8%) children were already in or en route to a HCF when the PCCs was contacted, including 84.4% for 6–12-year olds and 89.0% for 13–19-year olds. The percentage for 6–19-year olds decreased from the pre-pandemic (89.2%) to pandemic (87.5%) periods (Table 1).

Highest Level of Health Care Received

More than two-thirds of children 6–12 years old (67.4%) and 13–19 years old (70.9%) were admitted to a HCF. The proportion of children admitted to a CCU decreased from 20.0% during the pre-pandemic period to 17.8% during the pandemic, while the proportion of children admitted to a non-CCU increased from 16.1% during the pre-pandemic period to 17.8% during the pandemic. The proportion of children admitted to a psychiatric facility remained relatively constant from pre-pandemic (34.7%) to pandemic (34.9%) periods (Table 1).

Medical Outcome

Among the 91.7% (n = 505,037) of cases that were followed to a known medical outcome, 26.0% had no effect, 38.5% had a minor effect, and 35.5% had a serious medical outcome, including 482 deaths. The proportion of cases with a serious medical outcome was greater among children 13–19 years old (35.7%) than children 6–12 years old (32.0%). When comparing medical outcomes of the pre-pandemic to pandemic periods, the proportion of individuals with no effect went from 26.5 to 24.8% and those with a serious medical outcome went from 35.0 to 36.9% (Table 1).

Trends

The trends in cases reported to US PCCs involving suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–19 years old were evaluated using an interrupted time series analysis. The estimated step change was − 1622 (95% CI − 3197 to − 47) and the estimated change in slope was 155 (95% CI − 359 to 669). This means that after the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, there was an immediate decrease of 1622 suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts, followed by an increase of 155 suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts every month. Figure 3 shows the values predicted by the ARIMA model in absence of the pandemic (counterfactual) compared with the observed values. The model indicated that there were 11,876 (95% CI 11,663–12,092) fewer cases than expected managed by US PCCs related to suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–19 years old from March 1, 2020, to February 28, 2021. There were no specific NPDS substance categories that disproportionately accounted for the observed trends (data not shown).

Number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–19 years old reported to United States poison control centers from March 2017–February 2021 compared with forecasted number from March 2020–February 2021, National Poison Data System. The vertical line in the figure indicates the start of the COVID-19 pandemic period (March 2020–February 2021). The pre-COVID-19 pandemic period was March 2017–February 2020. Forecasted numbers are based on the ARIMA model.

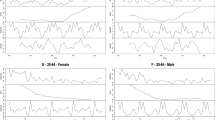

Suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–12 years old and 13–19 years old showed a seasonal trend, with an increase in the average monthly number of cases occurring during the school months of September through May. This pattern was seen in both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. There was no statistically significant difference in the average monthly number of cases during school and non-school months between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods in both the age groups (Fig. 4). Suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts also showed a weekly pattern with a greater average daily number of cases on Monday through Friday compared with weekend days for both 6–12- and 13–19-year olds. There was no statistically significant difference in the average daily number of cases on weekdays and weekends between pre-pandemic and pandemic periods (Fig. 5).

Average number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–12 years old reported to United States poison control centers during school and non-school months and days during pre-COVID pandemic (annual average) and COVID pandemic periods, National Poison Data System, March 2017–February 2021. The Y-axis scales are different for the two age groups. School months include September–May and non-school months include June–August. School days include Monday–Friday and non-school days include Saturday and Sunday.

Average number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 13–19 years old reported to United States poison control centers during school and non-school months and days during pre-COVID pandemic (annual average) and COVID pandemic periods, National Poison Data System, March 2017–February 2021. The Y-axis scales are different for the two age groups. School months include September–May and non-school months include June–August. School days include Monday–Friday and non-school days include Saturday and Sunday.

Discussion

There was a 4.5% increase in the number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–19 years old reported to US PCCs from the pre-pandemic (annual average) to COVID-19 pandemic periods. Most (94.1%) suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts involved teenagers 13–19 years old, peaking at ages 15–16 years during both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods with an observed shift in the age distribution toward younger age during the pandemic period (Fig. 2). The reason for this shift during the pandemic toward younger individuals is unknown and deserves further research. The observed increase in suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among 6–19-year olds is not attributable to an overall increase in reporting to PCCs during the pandemic. In fact, there was a 6.3% decrease in the number of reported exposures to PCCs involving individuals 6–19 years old from 373,293 (annual average) to March 2017–February 2020 to 349,879 for March 2020–February 2021. The ratio of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts to total exposures increased from 36.5% for March 2017–February 2020 to 40.7% for March 2020–February 2021.

The temporal trends of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts observed during the first year of the pandemic in this study should be considered as representing two phases. During the first phase, there was a greater than expected decrease in the number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts during the initial three months of the pandemic, which coincided with the timing of the typical annual decline in these cases being reported to US PCCs; however, the decrease occurred earlier (April rather than June) and persisted longer than expected (Fig. 3). This observed decline exceeded the 95% CIs of the forecasted numbers in the ARIMA model and accounted for the almost 12,000 fewer cases than expected during the pandemic period. These findings are consistent with those of another study that reported an initial decrease in emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among individuals 12–25 years old during the early months of the pandemic compared with the corresponding period in 2019, but then began to increase (compared with 2019) starting in May 2020, especially among adolescent girls 12–17 years old [10]. A similar pattern was seen among individuals of all ages in Japan, where monthly suicide rates declined by 14% during February to June 2020, followed by an increase of 16% during July to October 2020 [9].

The observed initial greater-than-expected decrease in suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts may be attributable to increased family contact, openness about feelings, and overall social cohesion as people came together and supported each other during the initial phase of a crisis. A decrease in suicides has been seen following similar crises, including the 1918 influenza pandemic [18]. In our study, the decrease was transient, which may be attributable to a waning of the initial family engagement and social connectedness over subsequent months as the pandemic continued.

The second phase of the observed trend in this study represented an increase in the number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts reported to US PCCs during the remainder of the first year of the pandemic, which agreed with the projections of the ARIMA model (Fig. 3). The overall increase in this study is consistent with research that reported an increase in the proportion of adolescents screening positive for depressive symptoms and suicidal risk and an increase in the number of emergency department visits and pediatric intensive care unit admissions for suspected suicide attempts among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic [3, 10, 19,20,21]. The findings of this study agree with those reported for suicide-related calls to PCCs in France during the pandemic, which showed a significant decrease in calls during the initial pandemic months followed by a second phase represented by an increase in calls, primarily involving young females [11]. Two studies reported an overall increase in pediatric suicides reported to US PCCs between 2000–2020 and 2015–2020, respectively; however, the pandemic period was not specifically compared with the pre-pandemic period, analyses were not done by month, and only percent-changes were calculated [7, 8]. In contrast, a study of suicide-related calls to the California Poison Control System revealed a decrease during the pandemic, including among the age group 12–17 years old [12].

Possible explanations for the observed increase in suspected poison-related youth suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts during the second phase of the pandemic include increasing social isolation and reduced community support, family stress, heightened depression, anxiety and uncertainty, loss of routines and opportunities, economic stress, trauma and loss, increased substance use, and reduced access to mental health services and health care [22,23,24]. Adolescents also may be more vulnerable to these risk factors and have been shown to be at higher risk of suicide after natural disasters [25]. The rising concern about child and adolescent mental health challenges associated with the pandemic led the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and Children’s Hospital Association to declare a national emergency in 2021 [26].

Recognizing the biphasic temporal trend in this pandemic may help guide an appropriate public health response to similar future crises. Pre-crisis planning and development of an improved system of mental health policies, infrastructure, and services are needed [26], which can then be followed by early initiation of evidence-based interventions (even if initial suicide numbers appear to be decreasing) in the home and community that target risk and resilience factors for suicide among youth in the event of a similar future crisis.

The average monthly number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–12 years old and 13–19 years old reported to US PCCs was greater during school months than non-school months during both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods with more cases seen in each age group and month category during the pandemic. These findings are consistent with previous studies, which reported higher youth suicide rates during school months [15, 27, 28]. A similar pattern was seen for the average daily number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts during weekdays versus weekends with more cases occurring on weekdays and during the pandemic period; this was true for both 6–12- and 13–19-year-old age groups. One prior study reported that suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts were higher on Mondays and Tuesdays among children < 19 years old [29]. The reasons why these patterns persisted during the pandemic, when many schools were closed and learning was conducted virtually, could not be determined by this study but may indicate that the academic and social pressures of school persisted regardless of whether school was conducted in-person or virtually.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. The NPDS is a passive surveillance system that relies on voluntary reporting; therefore, it underestimates the true number of substance-related suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts because some are managed in medical or mental health settings without contacting a PCC. Discrepancies between death certificate data and NPDS fatality data have been previously reported [30]. Changes in the number of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods may be attributable to changes in suicidal behavior or reporting to the NPDS. Another limitation of the NPDS is that the self-reported data cannot be completely verified by PCCs or America’s Poison Centers. The NPDS cannot identify repeat exposures to the same individual because it does not use personal identifiers. Reported exposures do not necessarily represent a poisoning or overdose. Misclassification and missing data in a large database, such as the NPDS, do occur but are minimized by use of quality control and follow-up protocols by trained specialists. Furthermore, US census data for 2020 and 2021 were unavailable at the time of analysis, so rates were not calculated. The findings from statistical modeling have large confidence intervals and should only be considered valid for the duration of the study period. Despite these limitations, the NPDS is a high-quality national database that has been repeatedly used to evaluate national poisoning trends, including those associated with suicide and nonfatal suicide attempts [15, 16].

Conclusions

The findings of this study are consistent with those of other studies. Compared with the pre-pandemic period, there was a 4.5% increase in the number of cases of suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among children 6–19 years old reported to US PCCs during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. There were 11,876 fewer cases than expected, attributable to a greater than expected decrease in cases during the early months of the pandemic. Recognizing the biphasic temporal trend in suspected suicides and nonfatal suicide attempts among youth demonstrated during this pandemic can help guide an appropriate public health response to similar future crises.

Data Availability

Data analyzed in this study were from the National Poison Data System, which is owned and managed by America’s Poison Centers. Data requests should be submitted to America’s Poison Centers.

Abbreviations

- ARIMA:

-

Autoregressive integrated moving average

- CCU:

-

Critical care unit

- HCF:

-

Health care facility

- NPDS:

-

National Poison Data System

- PCC:

-

Poison control center

- US:

-

United States

References

Office of the Federal Register. Declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Federal Register. March 13, 2020;85(53):15337–15338. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/03/18/2020-05794/declaring-a-national-emergency-concerning-the-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak. Accessed November 14,2022.

National Center for Health Statistics. CDC WONDER, Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NCHS. 2022; https://wonder.cdc.gov. Accessed August 1, 2022.

Bruns N, Willemsen L, Stang A, et al. Pediatric ICU admissions after adolescent suicide attempts during the pandemic. Pediatrics. 2022;150(2): e2021055973.

Charpignon M-L, Ontiveros J, Sundaresan S, et al. Evaluation of suicides among US adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(7):724–6.

Ehlman DC, Yard E, Stone DM, Jones CM, Mack KA. Changes in suicide rates - United States, 2019 to 2020. MMWR. 2022;71(8):306–12.

Pirkis J, John A, Shin S, et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:579–88.

Ross JA, Woodfin MH, Rege SV, Holstege CP. Pediatric suicides reported to U.S. poison centers. Clin Toxicol. 2022;60(7):869–71.

Sheridan DC, Grusing S, Marshall R, et al. Changes in suicidal ingestion among preadolescent children from 2000–2020. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(6):604–6.

Tanaka T, Okamoto S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:229–38.

Yard E, Radhakrishnan L, Ballesteros MF, et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 2019–May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly. 2021;70:888–94.

Jollant F, Blanc-Brisset I, Cellier M, et al. Temporal trends in calls for suicide attempts to poison control centers in France during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2022;37(9):901–13.

Ontiveros ST, Levine MD, Cantrell FL, Thomas C, Minns AB. Despair in the time of COVID: a look at suicidal ingestions reported to the California Poison Control System during the pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(3):300–5.

Ciccotti HR, Spiller HA, Casavant MJ, Kistamgari S, Funk AR, Smith GA. Pediatric poison exposures reported to United States poison centers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Toxicol. 2022;60(12):1299–308.

American Association of Poison Control Centers. National Poison Data System Coding Users’ Manual. 2019; https://www.aapcc.org/national-poison-data-system. Accessed August 1, 2022.

Spiller HA, Ackerman JP, Smith GA, et al. Suicide attempts by self-poisoning in the United States among 10–25 year olds from 2000 to 2018: substances used, temporal changes and demographics. Clin Toxicol. 2020;58(7):676–87.

Spiller HA, Ackerman JP, Spiller NE, Casavant MJ. Sex- and age-specific increases in suicide attempts by self-poisoning in the United States among youth and young adults from 2000 to 2018. J Pediatr. 2019;210:201–8.

Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Ruch D, et al. Association between the release of Netflix’s 13 reasons why and suicide rates in the United States: an interrupted time series analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(2):236–43.

Hicks T. Why suicides have decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthline. 2021. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/why-suicides-have-decreased-during-the-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed August 1, 2022.

Lantos JD, Yeh HW, Raza F, Connelly M, Goggin K, Sullivant SA. Suicide risk in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2022;149(2): e2021053486.

Mayne SL, Hannan C, Davis M, et al. COVID-19 and adolescent depression and suicide risk screening outcomes. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3): e2021051507.

Radhakrishnan L, Leeb RT, Bitsko RH, et al. Pediatric emergency department visits associated with mental health conditions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, January 2019-January 2022. MMWR. 2022;71(8):319–24.

Gould MS, Lake AM, Kleinman M, Galfalvy H, Chowdhury S, Madnick A. Exposure to suicide in high schools: impact on serious suicidal ideation/behavior, depression, maladaptive coping strategies, and attitudes toward help-seeking. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(3):455.

Kaminski JW, Puddy RW, Hall DM, Cashman SY, Crosby AE, Ortega LA. The relative influence of different domains of social connectedness on self-directed violence in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(5):460–73.

Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):142–50.

Jafari H, Heidari M, Heidari S, Sayfouri N. Risk factors for suicidal behaviours after natural disasters: a systematic review. Malays J Med Sci. 2020;27(3):20–33.

American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Children’s Hospital Association. AAP-AACAP-CHA Declaration of a National Emergency in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2021; https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/. Accessed August 1, 2022.

Hansen B, Lang M. Back to school blues: seasonality of youth suicide and the academic calendar. Econ Educ Rev. 2011;30:850–61.

Lueck C, Kearl L, Lam CN, Claudius I. Do emergency pediatric psychiatric visits for danger to self or others correspond to times of school attendance? Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(5):682–4.

Beauchamp GA, Ho ML, Yin S. Variation in suicide occurrence by day and during major American holidays. J Emergency Med. 2014;46(6):776–81.

Hoppe-Roberts JM, Lloyd LM, Chyka PA. Poisoning mortality in the United States: comparison of national mortality statistics and poison control center reports. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(5):440–8.

Funding

Author, HC, received a student scholar research stipend from the Child Injury Prevention Alliance while she worked on this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hailee Ciccotti contributed to the conception and design of the study, conducted data analyses, and contributed to interpretation of data; she drafted the article, approved the final version to be published, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Henry Spiller contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and interpretation of data; he reviewed and revised the article critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Sandhya Kistamgari conducted data analyses and contributed to interpretation of data; she reviewed and revised the article critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Marcel Casavant and Alexandra Funk contributed to the interpretation of data; they reviewed and revised the article critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Gary Smith contributed to the conception and design of the study and interpretation of data; he reviewed and revised the article critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None.

Disclaimer

The interpretations and conclusions in this article do not necessarily represent those of the funding organization. The funding organization was not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional information

Supervising Editor: Richard Wang, DO

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Previous Presentation of Data: Not applicable

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ciccotti, H.R., Spiller, H.A., Casavant, M.J. et al. Pediatric Suspected Suicides and Nonfatal Suicide Attempts Reported to United States Poison Control Centers Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Med. Toxicol. 19, 169–179 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-023-00933-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-023-00933-7