Abstract

Introduction

Shame is a self-conscious emotion involving negative self-evaluations, being a transdiagnostic factor for psychopathology. Due to stigma and discrimination experiences related to having a minority sexual orientation, LGB+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other minority sexual orientations) people report higher levels of general shame than heterosexual people. To our knowledge, there is no specific measure of shame related to sexual orientation. This study aimed to develop and explore the psychometric properties of the Sexual Minority—External and Internal Shame Scale (SM-EISS) in a sample of Portuguese LGB+ people.

Method

The sample was recruited online between December 2021 and January 2022 and comprised 200 Portuguese LGB+ people (Mage = 27.8 ± 8.9) who completed measures about shame, proximal minority stressors, and mental health.

Results

Good psychometric characteristics were found for a second-order two-factor structure (general, external, and internal shame related to sexual orientation), with the SM-EISS demonstrating good reliability and validity values.

Conclusion

The SM-EISS seems to be a valid and reliable instrument to assess shame related to sexual orientation among LGB+ people and may be beneficial in clinical and research contexts.

Policy Implications

Measuring shame related to sexual orientation experienced by LGB+ people could enhance the clinical understanding of this population. It can help researchers and clinicians to better understand this emotion and how it affects LGB+ people’s mental health and well-being. The research has important implications for clinical practice, social interventions, and public policies to protect LGB+ people’s rights. This is especially relevant in Portugal, where, despite positive legal developments, LGB+ people continue to experience harmful situations that negatively impact their mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Portugal, although there have been positive developments in the legal recognition of rights for LGB+ people (i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other minority sexual orientations), such as the ability for same-sex couples to co-adopt (in 2016) and the recent prohibition of discrimination in blood donation eligibility (in 2021), these advancements have not necessarily translated into significant changes in this population’s life (Neves et al., 2023). An example is the reluctance that LGB+ people usually have to access healthcare services due to fear of discrimination and marginalization (Pieri & Brilhante, 2022). Another example is the existence of sexual orientation change efforts (usually referred to as “reparative or conversion therapy” or ex-gay therapy). Even though, in the last few decades, both the Order of Portuguese Psychologists (OPP, 2017, 2021) and the Portuguese Society of Clinical Sexology (reinforced in 2019, but highlighted 10 years earlier; Pascoal et al., 2019) have taken a stand against these negative practices, emphasizing their long-term harmful effects on people, conversion therapies continue to be a part of the lived experiences of LGB+ people in Portugal (Sousa et al., 2023).

Research on LGB+ people who have undergone conversion therapies consistently reveals alarming outcomes, including worsened mental and sexual health, increased suicide attempts, and higher levels of general shame compared to people who had not been subjected to those practices (Flentje et al., 2014; Ryan et al., 2020). Beyond the clinical context, violence is still present in educational and social contexts. For example, in Portuguese schools, most LGB+ students reported experiences of discrimination (Gato et al., 2020). Data included in the latest report by The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA, 2020) demonstrated that 57% of LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual, and other minoritized sexual orientations and gender identities) participants in Portugal were afraid of or felt uncomfortable holding hands in public, often avoiding it. Also, 30% of the LGBTQIA+ participants affirmed they were harassed the year before answering the survey. These investigations mirror the heteronormative context throughout life and in different contexts in Portugal.

Heteronormative contexts are associated with poorer mental health (e.g., isolation, phobia, self-harm, and suicidality, Wilson & Cariola, 2020). LGB+ people have a higher risk of mental health problems (Fulginiti et al., 2021), which seems to be explained by the Minority Stress Model: due to social discrimination and victimization experienced by LGB+ people (distal processes), some proximal processes help to explain lower levels of mental health (Frost & Meyer, 2023; Meyer, 2003). Expectations of rejection, concealment of sexual orientation, and internalized stigma are examples of these proximal processes and are present in different phases of life (Detwiler, 2015; Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017; Meyer, 2003). For example, Goldbach and Gibbs (2017) conducted a study on LGB+ adolescents and adapted this model to suit their specificities. The authors concluded that the Minority Stress Model is also applicable to LGB+ teenagers. It is important to note that sexual development during adolescence can act as an additional minority stressor. Also, Detwiler (2015) conducted a study on older LGB+ adults intending to adapt the Minority Stress Model, and showed that this model may also be suitable for LGB+ older adults with the additional minority stressor of age-related discrimination. Overall, findings indicate that the Minority Stress Model is suitable for both young and older LGB+ adults.

More specifically, according to the Minority Stress Model, LGB+ people may internalize these external events (stigma-related events) through cognitive processes (Meyer, 2020). Proximal processes appear as defensive mechanisms to avoid discomfort in interpersonal relationships and/or discrimination in social contexts (Carvalho et al., 2022; Frost & Meyer, 2023). However, although these defense mechanisms mitigate immediate discomfort, they may also increase the experience of general shame, a self-conscious emotion underlying social interactions (Tracy et al., 2007). As stated in the Evolutionary and Biopsychosocial Model of Shame (Gilbert, 2010), general shame is an evolutionary response to social threats, protecting the self from rejection and exclusion by others. General shame can result from internalized stigma (Brown & Trevethan, 2010) and is characterized by feelings of inferiority, social unattractiveness, defectiveness, and powerlessness (Tracy et al., 2007). Studies have consistently shown that general shame is associated with overall psychopathology (DeCou et al., 2021) and, possibly due to stigma, LGB+ people experience higher levels of general shame—a key aspect of LGB+ people’s identity development (McDermott et al., 2008)—when compared to heterosexual peers (Santos, 2021). The relationship between proximal and distal minority stressors and psychological and physical distress may be partially explained by the experience of general shame (Mereish & Poteat, 2015), which can negatively impact health and social relationships (e.g., Swee et al., 2021).

As a result of their experiences and processes, LGB+ people may feel shame, specifically regarding their sexual orientation. Therefore, it is crucial to incorporate this specificity of shame into therapeutic interventions and measure it accordingly to ensure better case formulations and tailored interventions.

Current Study

To our knowledge, there is no measure to assess shame related to sexual orientation. General shame measures exist, but they may not capture the specificities of LGB+ people that underline their lower mental health levels. One scale that measures general shame is the External and Internal Shame Scale (EISS; Ferreira et al., 2022), which presents good psychometric values. This scale is based on the Evolutionary and Biopsychosocial Model of Shame (Gilbert, 1998, 2010), which divides general shame into external and internal. This paper aimed to adapt the EISS and validate the Sexual Minorities External and Internal Shame Scale (SM-EISS) in a sample of Portuguese LGB+ people. Specifically, it aimed to explore its construct validity (factorial, convergent, and discriminant validities) and reliability (internal consistency, composite, and individual). We hypothesized that the SM-EISS would show good fit indexes for a second-order two-factor model (total score of general shame related to sexual orientation divided into external and internal shame related to sexual orientation) (H1); good reliability indexes (H2); significant, positive and moderate correlations with the general shame measure, proximal stress minority processes, and psychopathology symptoms (H3); and good discrimination validity between people with high and low levels of minority stress processes (H4).

Method

Participants

The SM-EISS was tested on 200 Portuguese adults who self-identified as LGB+. The sample characteristics are described in Table 1. The participants' mean age was 27.8 years old (SD = 8.9), and they were mostly women (53.5%) and cisgender (83%).

Measures

Demographics Overview

A demographic overview questionnaire assessed sociodemographic characteristics: age (i.e., open question), gender (i.e., woman, man, non-binary, other, prefer not to say), gender identity (i.e., cisgender, transgender, non-binary, other, prefer not to say), sexual characteristics (i.e., intersex, yes/no), sexual orientation (i.e., gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, asexual, other, prefer not to say), region of residence (i.e., North, Center, Lisbon and Tagus Valley, South, Azores, Madeira), area of residence (i.e., rural, urban), and currently having psychological treatment (yes/no). According to the American Psychological Association guidelines, gender-related and sexual orientation variables always included options “other” and “prefer not to say” (APA, 2020).

The External and Internal Shame Scale

EISS (Ferreira et al., 2022) is an 8-item self-report questionnaire to assess general shame (total score). It includes two factors: external (e.g., Others are judgmental and critical of me) and internal (e.g., I’m different and inferior to others) shame. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from Never (0) to Always (4), with higher scores suggesting higher levels of shame. In the original version, Cronbach’s alpha was .89 for the total score of shame, .80 for external shame, and .82 for internal shame. Cronbach’s alphas in this study were .91 for the total score of shame, .84 for external shame, and .83 for internal shame.

The Sexual Minority—External and Internal Shame Scale

SM-EISS is an 8-item self-report questionnaire assessing shame related to sexual orientation. Since this study aimed to adapt and validate the EISS to measure shame related to sexual orientation (SM-EISS) of people who self-identified as LGB+, some modifications were made to the original scale (EISS), as described in the Procedure section. In that way, the SM-EISS is an 8-item self-report inventory with a 5-point Likert scale that assesses general shame related to sexual orientation (total score) with two factors: external shame related to sexual orientation (e.g., Others are judgmental and critical of me due to my sexual orientation) and internal shame related to sexual orientation (e.g., I’m different and inferior to others due to my sexual orientation)

The Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale

LGBIS (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000; Oliveira et al., 2012) is a 28-item self-report inventory assessing the multidimensional identity of LGB+ people, rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from Totally disagree (1) to Totally agree (7). The LGBIS is composed of 7 factors: identity dissatisfaction (F1), identity uncertainty (F2), concealment motivation (F3), difficult process (F4), identity centrality (F5), stigma sensitivity (F6), and identity superiority (F7). The Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.76 to 0.89. in the original version and between .62 and .83 in the Portuguese version. In this study, only three factors (F1, F3 and F6) were used, since they represent the proximal minority stressors: F1 represents internalized stigma, F3 represents concealment, and F6 represents expectations of rejection. Higher levels of F1 indicate a higher negative evaluation of sexual orientation and reflect higher levels of internalized stigma (e.g., If it were possible, I would choose to be straight). Higher levels of F3 suggest a higher motivation to keep sexual orientation private (e.g., I think very carefully before coming out to someone). Higher levels of F6 suggest that people anticipate more rejection based on sexual orientation (e.g., I can’t feel comfortable knowing that others judge me negatively for my sexual orientation). In the original version, the Cronbach alpha for F1, F3, and F6 were .88, .76, and .77 respectively. In the Portuguese version, the Cronbach alpha for F1, F3, and F6 were .83, .81, and .81 respectively. Cronbach’s alphas of these factors in this study were .84 for the F1, .84 for the F3, and .88 for F6.

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale—21 Items

DASS-21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2004) is a 21-item self-reported scale to assess psychopathological symptoms. It measures three main areas: depressive symptoms (e.g., I felt life had no meaning), anxiety symptoms (e.g., I was aware of the action of my heart in the absence of physical exertion), and stress symptoms (e.g., I found it difficult to relax), each composed of seven items. Respondents are asked to report their experience of those symptoms over the previous week on a 4-point response scale ranging from Did not apply to me at all (0) to Applied to me very much or most of the time (3). In the original version, Cronbach’s alpha was .91 for depression, .84 for anxiety, and .90 for stress symptoms subscales. In the Portuguese version, Cronbach’s alpha was .85 for depression, .74 for anxiety, and .81 for stress symptoms subscales. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .92 for depression and .91 for both anxiety and stress symptoms subscales.

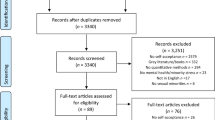

Procedure

The current online, cross-sectional study data were collected between December 2021 and January 2022. Recruitment was performed on social media and through the snowball-like technique. The host ethics committee approved the present study. The online survey containing the free and informed consent, sociodemographic questions, and the measures reported above was created through LimeSurvey@ within the host institution’s server. Details about the aims of the study, the eligibility criteria, and the voluntary nature of participation were provided. The database did not save any IP addresses or geolocation data, so the confidentiality and anonymity of the data were guaranteed, and all information collected was password-protected and accessible only to the research team. Inclusion criteria were self-identify as an LGB+ person, be over 18 years old, and fully complete the questionnaires. There was no financial compensation for the participants. SM-EISS is an adapted version of EISS considering specific shame related to sexual orientation. All participants completed the 8-item experimental version after permission for adaptation and use was obtained from the EISS authors. The authors of this study adapted the items, considering their expertise in working with LGB+ people. The new items were shared with the EISS authors, who approved this new scale version (SM-EISS). An example of modifications is changing the item I’m isolated (original version) from I and isolated due to my sexual orientation (this version).

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed in the IBM SPSS, Version 27 (IBM, 2020) and IBM AMOS, Version 25 (Arbuckle, 2020). In the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), similarly to what was done in the EISS, the estimation method used was the Maximum Likelihood (ML), and the tested model was a second-order two-factor model. The fit indices ascertained were Chi-square (χ2/df), Normed Chi-square (NCS), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR). Chi-Square should be nonsignificant, although this index is rarely considered reliable when the sample size is large (van de Schoot et al., 2012). Values of NCS should be between 2 and 3 (Hooper et al., 2008). For CFI, TLI, and GFI, values above 0.90 should reflect a good fit (Marôco, 2014; Schumacker & Lomax, 2016). For RMSEA and SRMS, values below 0.80 were acceptable (Hair et al., 2019; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). When the model does not have a good fit, it is modified based on the software’s suggested modification indices (Hair et al., 2019). The Fisher z-test was used to assess and compare the magnitudes of correlations. Internal consistency was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha, and values below 0.50 were considered unacceptable, from 0.50 to 0.59, poor; from 0.60 to 0.69, questionable; from 0.70 to 0.79, acceptable; from 0.80 to 0.89, good; and above 0.90, excellent (George & Mallery, 2019). Values above 0.70 and 0.25 were considered appropriate for composite and individual reliability, respectively (Marôco, 2014). Correlation coefficients below 0.30 were considered weak; between 0.40 and 0.60, moderate; and above 0.70, strong (Dancey & Reidy, 2020). Differences in shame were examined through independent sample t-tests to analyze the discriminant validity. Groups were obtained through this sample’s means and standard deviation scores; people with scores higher than the mean plus one standard deviation were compared to those with scores lower than the mean minus one standard deviation in the proximal minority stress variables. To examine the effect sizes of means difference, Cohen’s d was used (0.20 = small effect, 0.50 = medium effect, and 0.80 = large effect; Cohen, 1988).

Results

Preliminary Results

No severe violations of normality were found (|Sk|< 2 and |Ku|< 4) in any variable. Some moderated outliers were found in anxiety symptoms (6%), total score and internal shame related to sexual orientation (both 4.5%), and internalized stigma (3%). We decided not to eliminate the outliers to keep the natural variance (Osborne, 2008), ensuring ecological validity.

Construct Validity

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

A CFA was conducted to confirm the second-order two-factor model hypothesized, similar to the procedure used in the original version. This model did not adequately fit the subsample (RMSEA = 0.10). The modification indices indicated several correlations between errors. The first suggested modification was tested to improve the model fit—correlation between 4 and 7 item errors (both belonging to the second factor). With this refinement, the model presented a good fit index. All regression weights were significant, and all loadings were above 0.66. Although chi-square was significant (χ2(18) = 45.78, p < 0.001), the NCS presented a good value (2.55), as well as the CFI, TLI, GFI, RMSEA, and SRMR (CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.94; GFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.09; SRMR = 0.05). Figure 1 presents the CFA model.

Convergent Validity

First, it was important to test the correlations with the original measure of shame: on one hand, to confirm the association of the new specific shame measure with a general shame measure (no association would imply different constructs); on the other hand, to assess the relevance of having a specific scale to measure shame in this particular population (a too high association would imply that both measures were assessing the same construct, and therefore there would be no need for a specific measure). Second, we decided to test correlations with the proximal minority stress processes characteristic of this population, which were therefore expected to be positive and significantly correlated with the new measure. Third, it was important to test correlations with psychopathology symptoms, since studies show that general shame is strongly associated with psychopathology also in LGB+ people.

All correlations were positive and significant. Correlations of the total score of shame, external, and internal shame related to sexual orientation with the correspondent total and factors of the general measure of shame were all moderate. Considering the correlations of the shame related to sexual orientation with the proximal minority stress processes, all correlations were moderate, except external shame related to sexual orientation with internalized stigma and concealment. All correlations of the total score and factors of shame related to sexual orientation and psychopathology symptoms were moderate.

When comparing the correlations between the total scores and factors of the general shame measure and the specific shame related to sexual orientation with proximal minority stress processes, although there was a tendency for higher correlations with the specific shame measure, only the correlation of internal shame related to sexual orientation and internalized stigma was significantly higher than the correlation between general internal shame and the same construct (z = 3.07, p = 0.002). All means and correlations are presented in Table 2.

Discrimination Validity: Differences in Shame Related to Sexual Orientation as a Function of Proximal Stressors

People with high levels of internalized stigma, concealment, and expectations of rejection were compared with people with low levels of the same variables in total, external and internal shame related to sexual orientation scores (Table 3). Results have shown that people with high levels of proximal minority stress processes had higher levels of total, external, and internal shame related to sexual orientation compared to people with low levels of the same variables (medium effect size). The only non-significant comparison emerged in the comparison of low and high internalized stigma scores in external shame related to sexual orientation (p = 0.72).

Reliability

Internal Consistency, Composite and Individual Reliability

The total score showed an excellent internal consistency (α = 0.91), and the two factors showed good internal consistency (α = 0.84 and α = 0.83, for external and internal shame, respectively). The mean and standard deviation of each item, item-total correlation, and alpha if the item was deleted can be found in Table 4. No item, when removed, improved the scale’s alpha value. Item-total correlations ranged between 0.64 and 0.69 in external shame related to sexual orientation and between 0.60 and 0.73 in internal shame related to sexual orientation. Considering the composite reliability, the values obtained were appropriate (0.90, 0.84, and 0.78 for the total score and external and internal shame, respectively). Finally, the individual reliability values were above 0.45, which revealed a good fit. The total score showed a strong correlation with external (r = 0.92) and internal shame (r = 0.88). The factors showed a moderate intercorrelation (r = 0.62), showing that although these factors are related, they are measuring different constructs. In sum, all indexes of reliability showed good values.

Discussion

To our knowledge, there were no specific scales of shame related to sexual orientation when this may be a specificity impacting the mental health of LGB+ people. For that reason, we aimed to adapt a general shame scale to reflect shame related to sexual orientation and to study its psychometric properties. The validity and reliability of the Sexual Minorites External and Internal Shame Scale (SM-EISS) (Appendix) were tested, an adaptation of the External and Internal Shame Scale (EISS; Ferreira et al., 2022) in a sample of Portuguese LGB+ people. The CFA demonstrated an excellent overall fit and confirmed the original second-order two-factor model, corroborating our first hypothesis (H1). Although the SM-EISS RMSEA value was low, according to statistical guidelines (Kenny et al., 2015), researchers should not consider high RMSEA values problematic when the df is small. As the df decreases, the variability sampling of RMSEA increases. The total score measures feelings of shame related to sexual orientation, with two factors: external shame related to sexual orientation (the assumption that others negatively perceive the self due to their non-normative sexual orientation) and internal shame related to sexual orientation (self-perception as inadequate and defective due to their non-normative sexual orientation). These results are aligned with the theoretical framework of general shame used in this study (Gilbert, 1998, 2010), distinguishing external and internal shame, specifically regarding non-normative sexual orientations. Following the guidelines for establishing correlations among errors, we have implemented a procedure encompassing items with shared variance and a rationale grounded in theoretical principles. As indicated by the modification indices, we correlated two errors (errors 4 and 7 from internal shame related to sexual orientation), and a final adjusted model was achieved. The correlation between errors 4 and 7 (I am different and inferior to other people due to my sexual orientation and I am a worthless person due to my sexual orientation, respectively) may suggest that people who perceive themselves as inferior because of their sexual orientation are more likely to internalize negative beliefs and perceive themselves as worthless. Additionally, the SM-EISS also showed good reliability, corroborating H2 and suggesting that this scale consistently and accurately measures what it intends to measure—shame related to sexual orientation.

Our third hypothesis was partially confirmed. The total and factors of the SM-EISS presented a significant, positive, and moderate association with the total and factors of the EISS and with psychopathology. The associations of external shame related to sexual orientation with internalized stigma and concealment were low (instead of moderate, as hypothesized). The highest association of internalized stigma was with internal shame related to sexual orientation (moderate correlation), supporting that although internal shame related to sexual orientation may have similarities with internalized stigma, they are conceptually heterogeneous constructs (Allen & Oleson, 1999). A recent longitudinal study (Pachankis et al., 2023) also highlighted a significant difference between internalized stigma and general shame. The study found that internalized stigma was not strongly associated with general shame and did not explain the correlation between exposure to interpersonal stigma and poor mental health, which general shame did. On the one hand, this result highlighted that levels of internalized stigma are more associated with the internalization of negative judgments related to sexual orientation and that the creation of a sense of self around those judgments seems to lead to self-devaluation and internal conflict. The Minority Stress Model (Frost & Meyer, 2023; Meyer, 2003) proposes that internalized stigma comes from internalizing social stigma, and LGB+ people evaluate themselves according to this homonegativity (Ünsal & Bozo, 2022). On the other hand, a high motivation to keep sexual orientation private presented a low association with external shame related to sexual orientation, being more associated with internal shame related to sexual orientation. Our hypothesis for this result is based on the Cognitive Models (e.g., Young et al., 2003). During childhood and adolescence, social stigma can lead to intense shame experiences because of the increased social comparison in those years (Gilbert & Irons, 2009). It is possible that during the internalization of beliefs, external shame related to sexual orientation (i.e., the belief that others negatively evaluate the self) may have been more related to trying to maintain a sense of belonging to the group (Gilbert, 2010). Concealment of one’s sexual orientation may be one way to achieve this sense of belonging. The Biopsychosocial Model of Shame (Gilbert, 2002, 2007) suggests that internal shame can be a defensive response to external shame, resulting in negative self-evaluations and identification of oneself in the minds of others to restore one's self-image (Gilbert, 1998). However, after shame related to sexual orientation became internalized, already in adulthood (our sample had a mean age of 28), the self may start to hide the sexual orientation predominantly due to the idea that one is inadequate and defective because of it (internal shame related to sexual orientation), therefore less influenced by how others see the self (external shame related to sexual orientation). External and internal shame related to sexual orientation seem to be, therefore, two types of shame that co-exist and depend on each other. For example, if LGB+ people believe to be defective due to sexual orientation, they may also believe that others see them as defective for the same reason. Also, if a person thinks that they exist in others’ minds as defective due to their sexual orientation, they can internalize that they are defective due to the same reason. In turn, hiding sexual orientation is shameful for the person him/herself (Ünsal & Bozo, 2022) and may increase external and internal shame related to sexual orientation. Given the novelty of these results, future studies specifically focused on external and internal shame related to sexual orientation and concealment would be warranted.

As predicted in our fourth hypothesis (H4), the associations of the total and factors of the SM-EISS with proximal stress processes were almost all higher than the associations between the total and factors of the EISS and the same stress processes. The only exception was the association between external shame and internalized stigma. Despite this general direction of the results, the only correlation difference that reached statistical significance was the difference between the correlation of general internal shame with internalized stigma and of internal shame related to sexual orientation with internalized stigma, with the latter being significantly higher. Overall, the SM-EISS seems to be adapted to assess specific shame related to sexual orientation.

Finally, the SM-EISS revealed a good ability to discriminate between people with low and high levels of all proximal stress processes. LGB+ people with higher levels of internalized stigma, concealment, and anticipation of rejection presented significantly higher levels of shame related to sexual orientation (both external and internal) when compared with peers with low internalized stigma, concealment, and anticipation of rejection (corroborating H5).

According to the results of this study, we suggest that shame related to sexual orientation may fit into the Minority Stress Model. This is because the Minority Stress Model posits that LGB+ people experience stress because of being part of a stigmatized group, which exposes them to distal stressors. These distal stressors can become internalized, leading to negative mental health outcomes in LGB+ people. Shame related to sexual orientation may represent one way in which these distal stressors are internalized. When LGB+ people experience discrimination or societal stigma due to their sexual orientation, they may internalize these negative messages, resulting in feelings of shame about their identity, feeling unworthy, uninteresting, and inferior to others due to the sexual orientation both in interpersonal and intrapersonal relationships. This internalized shame related to sexual orientation becomes a direct source of stress that contributes to mental health disparities among LGB+ people. Therefore, integrating shame related to sexual orientation into the Minority Stress Model as a proximal stressor may provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding the psychological processes underlying the experiences of LGB+ people.

Limitations

Despite the relevant results, this study has several limitations. The first limitation is related to online recruiting. Participants of online recruitment are predominantly white, middle to upper class, and educated (Dillman et al., 2014), excluding people with difficulties in using the internet, usually from other ethnicities and education levels. Therefore, it should be noted that the present sample may not provide an accurate representation when taking into account intersectionality. However, online recruitment can also be seen as an advantage since online surveys increase the participation of underprivileged populations, possibly due to the sense of anonymity (Trau et al., 2013). Also, online recruitment may reach people in diverse geolocalizations (Trau et al., 2013).

It is also crucial to ensure a more balanced sample considering a larger spectrum of non-normative sexual orientations, allowing accurate generalizations of results. Future investigations should aim to replicate these findings to validate and strengthen the current study’s results.

Conclusions

This research not only builds upon previous research but also deepens our understanding of the specific challenges faced by LGB+ people. SM-EISS may be a helpful questionnaire to inform researchers and clinicians about risk factors for developing and maintaining psychological problems in this population. Also, a validation of a standardized questionnaire may enable clinicians to assess and address shame related to sexual orientation in clinical settings effectively, thereby informing clinical interventions. The implications of this research also extend to social interventions and policymaking, particularly in social and political contexts such as Portugal, where LGB+ people still encounter harmful experiences despite positive legal developments, leading to lower mental health levels.

Based on the results mentioned above, it can be concluded that the SM-EISS is a valid and reliable tool for evaluating shame related to sexual orientation in both clinical and research contexts. This assessment instrument is valuable to the existing measures and contributes to the literature on LGB+ people. In fact, this study introduces the first-ever tool to measure shame related to sexual orientation. We proposed that this specific type of shame may be integrated into the Minority Stress Model (Meyer, 2003) as a proximal stressor. This integration would provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding the psychological processes underlying the experiences of LGB+ people. It is essential to recognize the impact of this shame on the health of this population and to use culture-sensitive approaches in clinical work, such as the affirmative approach (e.g., Pachankis et al., 2022).

Data Availability

The data presented in this study can be available on request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Allen, D. J., & Oleson, T. (1999). Shame and internalized homophobia in gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 37(3), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v37n03_03

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

Arbuckle, J. L. (2020). Amos 27.0 User’s Guide.

Brown, J., & Trevethan, R. (2010). Shame, internalized homophobia, identity formation, attachment style, and the connection to relationship status in gay men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 4(3), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988309342002

Carvalho, S., Castilho, P., Seabra, D., Salvador, C., Rijo, D., & Carona, C. (2022). Critical issues in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with gender and sexual minorities (GSMs). The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 15, E3. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X21000398

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dancey, C. P., & Reidy, J. (2020). Statistics without maths for psychology (8th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

DeCou, C. R., Lynch, S. M., Weber, S., Richner, D., Mozafari, A., Huggins, H., & Perschon, B. (2021). On the association between trauma-related shame and symptoms of psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Trauma, violence, & abuse. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211053617

Detwiler, B. P. (2015). Minority stress in the sexual minority older adult population: Exploring the relationships among discrimination, mental health, and quality of life. Lehigh University.

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed mode surveys: The tailored design method (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2020). EU LGBTI survey II. A long way to go for LGBTI equality: Country data – Portugal.

Ferreira, C., Moura-Ramos, M., Matos, M., & Galhardo, A. (2022). A new measure to assess external and internal shame: Development, factor structure and psychometric properties of the external and internal shame scale. Current Psychology, 41, 1892–1901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00709-0

Flentje, A., Heck, N. C., & Cochran, B. N. (2014). Experiences of ex-ex-gay individuals in sexual reorientation therapy: Reasons for seeking treatment, perceived helpfulness and harmfulness of treatment, and post-treatment identification. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(9), 1242–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.926763

Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2023). Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Current Opinion in Psychology, 51, 101579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101579

Fulginiti, A., Rhoades, H., Mamey, M. R., Klemmer, C., Srivastava, A., Weskamp, G., & Goldbach, J. T. (2021). Sexual minority stress, mental health symptoms, and suicidality among LGBTQ youth accessing crisis services. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 893–905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01354-3

Gato, J., Leal, D., Moleiro, C., Fernandes, T., Nunes, D., Marinho, I., & Freeman, C. (2020). “The worst part was coming back home and feeling like crying”: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans students in Portuguese schools. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 504801. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02936

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2019). IBM SPSS statistics 25 step by step: A simple guide and reference (15th ed.). Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (1998). What is shame? Some core issues and controversies. In P. Gilbert & B. Andrews (Eds.), Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture (pp. 3–38). Oxford University Press.

Gilbert, P. (2002). Body shame: A biopsychosocial conceptualisation and overview, with treatment implications. In P. Gilbert & J. Miles (Eds.), Body shame: Conceptualisation, research and treatment (pp. 3–54). Brunner.

Gilbert, P. (2007). The evolution of shame as a marker for relationship security. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 283–309). Guilford Press.

Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge.

Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2009). Shame, self-criticism, and self-compassion in adolescence. In N. Allen & L. Sheeber (Eds.), Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders (pp. 195–214). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511551963

Goldbach, J. T., & Gibbs, J. J. (2017). A developmentally informed adaptation of minority stress for sexual minority adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 55, 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.007

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning EMEA.

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D79B73

IBM Corporation. (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0.

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114543236

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u

Marôco, J. (2014). Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, Software e Aplicações. ReportNumber.

McDermott, E., Roen, K., & Scourfield, J. (2008). Avoiding shame: Young LGBT people, homophobia and self-destructive behaviours. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 10(8), 815–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050802380974

Mereish, E. H., & Poteat, V. P. (2015). A relational model of sexual minority mental and physical health: The negative effects of shame on relationships, loneliness, and health. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(3), 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000088

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer, I. H. (2020). Rejection sensitivity and minority stress: A challenge for clinicians and interventionists. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(7), 2287–2289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01597-7

Mohr, J., & Fassinger, R. (2000). Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 33(2), 66–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2000.12068999

Neves, S., Ferreira, M., Sousa, E., Costa, R., Rocha, H., Topa, J., Vieira, C. P., Borges, J., Lira, A., Silva, L., Allen, P., & Resende, I. (2023). Sexual violence against LGBT people in Portugal: Experiences of Portuguese victims of domestic violence. LGBTQ+ Family: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 19(2), 145–159.

Oliveira, J. M., Lopes, D., Costa, C. G., & Nogueira, C. (2012). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity scale (LGBIS): Construct validation, sensitivity analyses and other psychometric properties. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 334–347. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n1.37340

Order of Portuguese Psychologists. (2017). Guia orientador da intervenção psicológica com pessoas lésbicas, gays, bissexuais e trans (LGBT). Lisboa, Portugal. Available online: https://www.ordemdospsicologos.pt/ficheiros/documentos/guidelines_opp_lgbt_marco_2017.pdf. Accessed on 6 July 2023.

Order of Portuguese Psychologists. (2021). OPP opinion—Conversion therapies. Lisbon, Portugal: Order of Portuguese Psychologists. Available online: https://recursos.ordemdospsicologos.pt/files/artigos/parecer_opp_terapias_de_convers__o.pdf. Accessed on 6 July 2023

Osborne, J. W. (2008). Best practices in quantitative methods. Sage publications.

Pachankis, J. E., Harkness, A., Jackson, S., & Safren, S. A. (2022). Transdiagnostic LGBTQ-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press.

Pachankis, J. E., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Klein, D. N., & Bränström, R. (2023). The role of shame in the sexual-orientation disparity in mental health: A prospective population-based study of multimodal emotional reactions to stigma. Clinical psychological science. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026231177714

Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., Honrado, A., & Leal, I. (2004). Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das Escalas de Ansiedade, Depressão e Stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 5(1), 229–239.

Pascoal, P. M., Moita, G., Marques, T. R., Carvalheira, A., Vilarinho, S., Cardoso, J., Carvalho, R. F., Almeida, M. J., & Nobre, P. J. (2019). Commentary: A position statement on sexual orientation conversion therapies by members of the board of directors of the Portuguese Society of Clinical Sexology (SPSC). International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 231–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2019.1642280

Pieri, M., & Brilhante, J. (2022). “The light at the end of the tunnel”: Experiences of LGBTQ+ adults in Portuguese healthcare. Healthcare, 10(1), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010146

Portuguese Society of Clinical Sexology. (2019). Tomada de posição sobre terapias para mudar a orientação sexual. https://spsc.pt/index.php/2019/01/11/tomada-de-posicao-sobre-terapias-para-mudar-a-orientacao-sexual/

Ryan, C., Toomey, R. B., Diaz, R. M., & Russell, S. T. (2020). Parent-initiated sexual orientation change efforts with LGBT adolescents: Implications for young adult mental gealth and adjustment. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(2), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1538407

Santos, D. L. R. A. (2021). Shame, coping with shame and psychopathology: A moderated-mediation analysis by sexual orientation [Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Coimbra]. http://hdl.handle.net/10316/96518

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2016). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. In a beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Routledge.

Sousa, E., Neves, S., Ferreira, M., Topa, J., Vieira, C. P., Borges, J., Costa, R., et al. (2023). Domestic violence against LGBTI people: Perspectives of Portuguese education professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136196

Swee, M. B., Hudson, C. C., & Heimberg, R. G. (2021). Examining the relationship between shame and social anxiety disorder: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 90, 102088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102088

Tabanchnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson.

Tracy, J. L., Robins, R. W., & Tangley, J. P. (2007). The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research. Theory and research. The Guilford Press.

Trau, R. N., Härtel, C. E., & Härtel, G. F. (2013). Reaching and hearing the invisible: Organizational research on invisible stigmatized groups via web surveys. British Journal of Management, 24(4), 532–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2012.00826.x

Ünsal, B. C., & Bozo, Ö. (2022). Minority stress and mental health of gay men in Turkey: The mediator roles of shame and forgiveness of self. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2022.2036532

van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P., & Hox, J. (2012). A checklist for testing measurement invariance. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(4), 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.686740

Wilson, C., & Cariola, L. A. (2020). LGBTQI+ youth and mental health: A systematic review of qualitative research. Adolescent Research Review, 5(2), 187–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00118-w

Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. The Guildford press.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to all participants who agreed to participate in this study. Andreia A. Manão expresses gratitude to Patrícia Pascoal for the support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). This work was supported by the Foundation of Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) under grant number SFRH/BD/143437/2019 (“Mental Health and Well-Being in Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual (LGB) People: Conceptual Model and Compassion-Based Intervention”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AAM: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing—original draft. DS: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, and writing—review and editing. MCS: conceptualization, supervision, and writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics and Deontology Commission of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra (approved on November 2nd, 2019).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. SM-EISS—Sexual Minority External and Internal Shame Scale

Appendix. SM-EISS—Sexual Minority External and Internal Shame Scale

Please focus on the following statements that describe common feelings. It is important to note that every person may experience these emotions differently. Read each statement carefully and select the number that best reflects how frequently you experience the described emotions. Use the scale provided below for your responses:

In several aspects of my life, I FEEL THAT… | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Other people see me as not being up to their standards due to my sexual orientation. | |||||

2. I am isolated due to my sexual orientation. | |||||

3. Other people do not understand me due to my sexual orientation. | |||||

4. I am different and inferior to others due to my sexual orientation. | |||||

5. Others are judgmental and critical of me due to my sexual orientation. | |||||

6. Other people see me as uninteresting due to my sexual orientation. | |||||

7. I am unworthy as a person due to my sexual orientation. | |||||

8. I am judgmental and critical of myself due to my sexual orientation. |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manão, A.A., Seabra, D. & Salvador, M. Measuring Shame Related to Sexual Orientation: Validation of Sexual Minority—External and Internal Shame Scale (SM-EISS). Sex Res Soc Policy (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-024-00976-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-024-00976-7