Abstract

Introduction

Patients with cancer and partners often face difficult and enduring sexual concerns. Reviews up to 2017 identified that the provision of a healthcare professional (HP)-led sexual support was not routine practice. Since 2017, there has been a burgeoning growth in research and evidenced-based interventions targeting HP’s sexual support provision in cancer care. Therefore, this review presents a synthesis of HP-led sexual support and factors impacting provision in cancer care from 2017 to 2022 to ascertain if sexual support in clinical practice has changed.

Methods

Using an integrative review design, searches were performed on five electronic databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, ProQuest, PubMed and PsycInfo), Google Scholar and manual review of reference lists from 2017 to 2022. Data extracted from studies meeting predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria was synthesised using thematic analysis. Papers were appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

Results

From the twelve empirical studies included, three themes were identified: (1) Theory–practice gap: HP’s recognition of the need to provide sexual support to patients with cancer and partners but current provision is lacking, (2) professional and organisational barriers to HPs providing sexual support for patients with cancer and (3) equipping HPs and enabling patients to discuss sexual challenges in cancer care could enhance delivery of sexual support.

Conclusion

Provision of HP-led sexual support in cancer care is still not routine practice and when provided is considered by HPs as sub-optimal.

Policy Implications

Providing HPs with education, supportive resources and referral pathways could enhance the provision of sexual support in cancer care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexual challenges as a result of a cancer diagnosis and treatment are well-documented, with between 25 and 94% of people across tumour groups affected (Bond et al., 2019; Downing et al., 2019; Maiorino et al., 2016). Distressing and long-lasting challenges can affect both a patient and their partner (Bober & Varela, 2012; Collaço et al., 2018) with potential for individuals from any tumour group to experience challenges including those with breast, gynaecological, colorectal, lung, head and neck, haematological and prostate cancers (Bober & Varela, 2012; Bond et al., 2019; Collaco et al., 2018; Downing et al., 2019; Groundhuis et al., 2019). For patients, sexual challenges can include difficult or painful intercourse, body image issues, emotional distress and relationship difficulties, and for partners, issues are often psychosocial in nature (Bober & Varela, 2012; Grondhuis Palacios et al., 2019; Traa et al., 2014; Vermeer et al., 2016). Sexual challenges resulting from cancer or treatment can continue for many years and may worsen over time (McLeod & Hamilton, 2013).

Healthcare guidelines recommend the provision of healthcare professional (HP)-led biopsychosocial sexual support to patients with cancer and partners across the treatment trajectory (Carter et al., 2018; NICE, 2020). Many HPs, worldwide, agree that patients face sexual challenges (Bober & Varela, 2012; Downing et al., 2019) and recognise it is within their professional role to provide sexual support (Oskay et al., 2014); however, this practice is not routine (Reese et al., 2017b). A review of sexual care provision, in which 24 of the 29 studies were from Western cultures, reported that HPs were more likely to inform patients of the potential impact on cancer treatment on sexuality (88%) than assess (21%) or address sexual challenges (22%) (Reese et al., 2017b). Studies of nurse-led sexual support provision in two European countries reported that while most participants agreed it was their role to provide sexual support, only a minority addressed sexual concerns routinely (11–13%) (Krouwel et al., 2015; Oskay et al., 2014). There are several known barriers which contribute to the lack of HP-led sexual support, and these include HPs’ personal embarrassment (Ferreira et al., 2015; Zeng et al., 2011), their lack of knowledge of sexual concerns (Ferreira et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2013; Oskay et al., 2014), a fear of being perceived by patients or partners as inappropriate (Ferreira et al., 2015), patient’s advanced age, gender or culture, a lack of policy, workplace culture and lack of clinical time (Ferreira et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2013; Oskay et al., 2014). Moreover, the evidence depicts that patients wish to discuss sexual challenges with HPs. Patients and partners are not satisfied with the current provision of sexual support in cancer care, identifying the need for improvement (Canzona et al., 2016; Gilbert et al., 2016; Wendt, 2017).

Over the last decade, globally, there has been growing research interest into the provision of sexual support in cancer care with subsequent published evidenced-based interventions seeking to improve the provision of sexual support in cancer care. Strategies employed within these studies have included education (Afiyanti, 2017; Bingham et al., 2022a; Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2012; McCaughan et al., 2021; Merriam & DiNardo, 2018; Quinn et al., 2019; Reese et al., 2019a, b; Wang et al., 2015), skills training (Afiyanti, 2017; Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Merriam & DiNardo, 2018; Reese et al., 2019a, b; Wang et al., 2015), communication frameworks (Bingham et al., 2022a; McCaughan et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2015), record reviews investigating sexual care practice (Jung & Kim, 2016), and introduction of a tiered model of sexual care provision (Duimering et al., 2020), with several studies reporting positive changes to HP sexual attitudes to providing sexual support and improved HP-led sexual support provision in clinical practice. Given the recent expansion of research in this field, it is timely and prudent to update previous literature reviews which have reviewed literature until 2017 (Reese et al., 2017b; Vassão et al., 2018) to ascertain the current provision of HP-led sexual support in cancer care and factors influencing clinical practice. This information can then inform future intervention design and implementation strategies to promote routine HP-led sexual support. The aim of this integrative review therefore was to examine the current provision of HP-led routine sexual support in cancer care over the past 5 years (2017 – 2022) and the key factors influencing provision of sexual support for patients with cancer and their partners. The research questions guiding this integrative review were: (1) From the HPs’ perspective, what sexual support is currently provided to patients and their partners by HPs in routine cancer care? (2) What are the factors currently influencing HP-led sexual support in routine cancer care?

Methods

An integrated review typology was selected to summarise this topic of interest given the variety of research methodologies adopted by the relevant literature (Doolen, 2017).

Data Sources and Search Strategy

This review was completed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA). The acronym PICo was applied to the research questions: Population — multidisciplinary HPs, Interest — provision of sexual support and Context — cancer care settings. Inclusion/exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1. Although sexual health is pertinent across the lifespan, HPs working with children and adolescents were excluded from this review as sexual behaviours are developmental, with prevalence, predictors and outcomes differing across age (Vasilenko, 2022). Supplement 1 provides the MEDLINE search strategy, which was informed by previous similar review search strategies (O’Connor et al., 2019; Reese et al., 2017b; Vassão et al., 2018) and finalised with an experienced subject librarian. Searches were conducted using five electronic databases, CINAHL, MEDLINE, ProQuest, PubMed and PsycInfo from 1 Jan 2017 to 31st July 2022. Databases were searched using a combination of keywords alongside suitable Boolean operators and truncation markers to maximise the search (Table 2). Further searches of Google Scholar and manual searches of reference lists of extracted articles were used to identify additional studies (SLB & CVC).

Data Screening

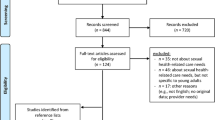

The initial search from the five electronic database searches and the grey literature were collated in RefWorks (being a reference management software tool) by CVC (co-author), generating a total of 844 studies, of which 82 duplicates were removed. The remaining 762 studies were reviewed by title and abstracts were screened independently for relevance by two authors (SLB and CVC), after which 42 papers were read in full. Once full-text articles were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 30 studies were excluded, resulting in 12 eligible papers. The process of identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion is displayed in a PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

Quality Analysis, Data Abstraction and Synthesis

Individual study quality was appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), independently by two reviewers (SLB, CJS), with disagreements managed by consensus (Hong et al., 2018). The MMAT can be used to indicate methodological quality (Hong et al., 2018) by determining whether study methods have achieved a pre-determined criterion. The MMAT includes two screening questions and five methodological questions specific to study design types. According to updated guidance on reporting of MMAT (Hong et al., 2018), reporting numerical output is discouraged but instead, it is recommended that a detailed presentation of the ratings of each criterion is presented. All studies, regardless of quality, were weighted equally in the synthesis.

Following reading and reading papers of the included studies, data relevant to study objectives was extracted independently by two authors (SLB, CVC) onto an extraction form generated by the research team, featuring the study author, year of publication, country, context (setting, location), study sample characteristics, intervention and key outcomes, barriers and facilitators to providing sexual support and study methodology (design, recruitment, sample size, response rate, outcome measures, data analysis and limitations). Extracted data were reviewed by the third author (CJS) for consistency and accuracy. In cases of disagreement, discussions with all authors took place, with final decisions being made by consensus. An inductive approach was adopted and deemed appropriate for data analysis synthesis, primarily due to the aim of this integrative review, in gaining an improved understanding of a complex phenomenon and generating higher-order themes following the aggregation of exiting evidence. In this context, the synthesis comprised of (1) examining main study findings (narrative and numerical) summarised as text to enable the development of a preliminary synthesis; (2) exploring relationships within and between studies; and (3) assessing the robustness of the synthesis (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

Thomas and Harden’s (2008) approach to thematic analysis was used to synthesise data and develop themes across and within selected studies. To facilitate this, the first author (SLB) coded findings line-by-line, which were then checked by the second author (CVC). Next, descriptive themes were developed at team meetings (all authors) which involved translating and comparing the concepts from one study to another and a hierarchical structure was created by grouping the codes based on similarities and differences between the codes and potential relationships to the findings. Finally, three analytical themes that went beyond the content of the original articles as relating to the research objectives were developed by SLB and refined by all authors at team meetings. Tables were created to manage coding and themes. NVivo V12 supported this process.

Results

Overview of Study Characteristics

This review included 12 articles with data from 972 HP participants. One hundred and fifty-one (15.6%) participants had previous sexual wellbeing training, although within this cohort, training varied from self-taught to degree-level (Ahn & Kim, 2020; Almont et al., 2019; Bedell et al., 2017; Wazqar, 2020; Williams et al., 2017). Research designs included quantitative (n = 8) and qualitative (n = 6). Studies originated from 10 countries with USA most represented (n = 3). Most HPs provided care for patients with gynaecological cancers, followed by breast; however, 6 studies did not provide HP breakdown by tumour site. The largest sample size was 165 HPs (France) (Almont et al., 2019), with a total of 7 studies with ≥ 100 participants. The study with the smallest sample was a qualitative study of seven HPs (Sweden) (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019). Most studies (n = 7) involved more than one HP discipline; however, medical personnel (oncologists, physicians and physician assistants) (n = 404) were included in 8 studies and nurses (n > 388) (one study grouped nurses, psychologist and physiotherapists under “paramedics”) were represented in 10 studies. Other professions represented within studies, although not delineated numerically, were radiotherapists, social workers, psychologists and physiotherapists. Table 3 summarises the study characteristics and main findings. The MMAT quality assessment (Supplement 2) identified overall that the study quality was good. Weaknesses identified in studies related to unknown response rates and potential for non-response bias given many of studies used convenience sampling approaches. These weaknesses have been addressed within strengths and limitations (“Strengths and Limitations” section).

Analysis of study findings identified three themes: (1) Theory–practice gap: HP’s recognition of the need to provide sexual support to patients with cancer and partners but current provision is lacking, (2) professional and organisational barriers to HPs providing sexual support for patients with cancer and (3) equipping HPs and enabling patients to discuss sexual challenges in cancer care could enhance delivery of sexual support. Of note, despite the dyadic nature of sexuality for those in relationships, these studies have focused on the HP-patient discussion with minimal reference to partners (Lynch et al., 2019).

Theory–practice gap: HP’s recognition of the need to provide sexual support to patients with cancer and partners but current provision is lacking

HPs recognised the impact of a cancer diagnosis and treatment on patient sexuality (Krouwel et al., 2020; Maree & Fitch, 2019; Williams et al., 2017), the value of providing routine sexual support across the cancer care treatment pathway (Almont et al., 2019; Lynch et al., 2019) and the consequences for the patient if such care is not provided (Williams et al., 2017). Maree and Fitch (2019) identified how all HP participants in their Canada and Zimbabwe cohorts agreed sexual support conversations were paramount to patient care. Similarly, a French study reported that 99% (n = 148) of physicians (n = 71) and paramedics which included nurses, physiotherapists, psychologists and biologists (n = 77) considered all patients following cancer treatment should have access to sexual support (Almont et al., 2019).

Although the need for HP-led sexual support is highly recognised amongst professionals, it is evident that the provision of sexual support in cancer care is inconsistently offered to patients or not available (Bedell et al., 2017; Krouwel et al., 2020; Lynch et al., 2019; Reese et al., 2017a). Reports on the frequency of provision of HP-led sexual support varied considerably across the studies, with a propensity for sexual support to be avoided or seldom addressed by the majority of HPs, irrespective of professional discipline, year experience or working across a range of tumour groups (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Lynch et al., 2019; Reese et al., 2017a). There was an acknowledgement amongst HPs that not addressing cancer patients’ sexual concerns depicted suboptimal care (Lynch et al., 2019). In contrast with most studies was a USA study of 124 HPs supporting patients with cervical cancer reporting that 64.4% (n = 80) of HPs provided sexual support regardless of being asked by the patient or partner (Bedell et al., 2017). Whereas Afiyanti (2017) reported that 73% (n = 99) of nurses indicated that HP-led sexual support was only provided when initiated by the patient. Of note, patients deemed too ill (Afiyanti, 2017; Almont et al., 2019; Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Krouwel et al., 2020; Reese et al., 2017a; Williams et al., 2017) or patients advanced in age were consistently less likely to receive support across studies (Almont et al., 2019; Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Krouwel et al., 2020; Reese et al., 2017a; William et al., 2017). However, there was some recognition that older patients would like to receive sexual support (Reese et al., 2017a). As reported in one study alone, HPs were also less likely to provide sexual support to non-heterosexual patients (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019). Furthermore, the presence of a spouse/partner/another could influence the discussion of sexual concerns between patient and HP, either positively or negatively (Williams et al., 2017). No further details are provided as to how the discussion was impacted.

More often, the timing of sexual support provision within clinical practice was not routinely reported across studies. Exceptions included two studies, with one indicating 75% (n = 90) of oncologists discussed sexual function with < 50% of patients as part of consent to treatment (Krouwel et al., 2020), albeit this excluded psychosocial aspects of sexuality. The other study indicated that 56% (n = 92) of HPs discussed sexuality issues prior to treatment, however, lacked detail on what was discussed (Almont et al., 2019). It was not clear from either of these studies if the timing of these discussions varied between tumour groups. The content of sexual support conversations, when described, was limited. Nonetheless, there was more focus on physical sexual concerns (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Krouwel et al., 2020) addressing topics such as libido, menopausal symptoms, lubrication, painful intercourse and erectile dysfunction (Krouwel et al., 2020) and risk avoidance (during chemotherapy) (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Bedell et al., 2017), rather than a holistic biopsychosocial approach (Maree & Fitch, 2019). It is important to note, that when HP-led support was provided, often HPs reported the quality of these interactions as unsatisfactory (Maree & Fitch, 2019; Reese et al., 2017a). Types of sexual support, when reported, included couple counselling (Almont et al., 2019), assessment and support for sexual challenges and provision of information (Almont et al., 2019; Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019). Two studies identified the use of onward referrals, with nurses forwarding patients to other professions such as sexologists, social workers, doctors and radiation oncologists (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Lynch et al., 2019). Overall, evidence suggests there is considerable scope to improve the provision of HP-led sexual support in cancer care.

Professional and organisational barriers to HPs providing sexual support for patients with cancer

Numerous professional and organisational barriers were presented across and within the included studies that prevented or inhibited the routine delivery of sexual support for patients with cancer. Professionally, HPs considered that sexual support held more relevance for some tumour groups such as prostate, gynaecological and breast (Lynch et al., 2019; Maree & Fitch, 2019) and that sexual support was not a priority topic at diagnosis or active treatment for HPs or patients (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Canzona et al., 2018; Maree & Fitch, 2019; Reese et al., 2017a; Williams et al., 2017). Further professionals’ barriers to progressing routine delivery of sexual support were HPs not considering the provision of sexual support as a legitimate clinical issue (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019) or believing it to be a taboo topic that should remain private (Afiyanti, 2017; Maree & Fitch, 2019; Williams et al., 2017). Studies reporting sexual support as taboo suggested this belief was influenced by conservative values instilled at an early age (Afiyanti, 2017; Williams et al., 2017) or by cultural factors (Afiyanti, 2017; Maree & Fitch, 2019) with Maree and Fitch’s (2019) African and Canadian cohorts reporting that in some cultures it is not appropriate for a person to talk about sexual concerns with another. Some HPs, irrespective of professional discipline, did not see the provision of sexual support as their role, reporting psychosocial counselling as the responsibility of another colleague (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Canzona et al., 2018; Lynch et al., 2019), though this was not the case for all (Afiyanti, 2017; Lynch et al., 2019). Provision of HP-led sexual support was further hindered by a HP belief that patients do not expect their HP to provide sexual support (Lynch et al., 2019).

Furthermore, personal discomfort, lack of confidence and embarrassment providing sexual support (Almont et al., 2019; Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Lynch et al., 2019; Maree & Fitch, 2019) were all established as HP-related barriers to providing sexual support in routine care. HPs did not wish to create any barriers in the HP-patient relationship (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Bedell et al., 2017; Reese et al., 2017a; Williams et al., 2017), concerned that this uncomfortable topic could be awkward for patients. One South Korean study identified an increased likelihood of provision of sexual support from HPs who are male, older or in a physician role (rather than being a nurse); with unmarried, female HPs confronting more barriers (Ahn & Kim, 2020) possibly indicating greater discomfort with the topic. A Dutch study of medical oncologists (male = 46.7%, male age = 50.6 (SD = 10), female age = 41.9 (SD = 8.9)) whose oncology experience ranged from 1 to over 15 years however reported no significant differences in the provision of sexual care based on HP gender, years of experience or age characteristics potentially indicating that the HP role influences comfort levels more so than other HP characteristics (Krouwel et al., 2020).

From an organisation perspective, cancer care settings presented a myriad of barriers, including a lack of time (Canzona et al., 2018; Reese et al., 2017a; Wazqar, 2020), privacy (Ahn & Kim, 2020; Lynch et al., 2019; Maree & Fitch, 2019; Wazqar, 2020; Williams et al., 2017), lack of guidelines (Lynch et al., 2019; Maree & Fitch, 2019) and colleagues not advocating the inclusion of sexual support in routine cancer care (Wazqar, 2020). Regarding time, many HPs believed there was a lack of time to assess sexual concerns and provide support (Canzona et al., 2018; Reese et al., 2017a; Wazqar, 2020). HPs discussed competing priorities and a fear that engaging in the topic could risk lengthy appointments affecting clinical schedules (Ahn & Kim, 2020; Canzona et al., 2018; Krouwel et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2017). Conversely, Almont et al. (2019) disputed that a lack of clinical time was a barrier to discussion of sexual concerns, indicating instead that it was lacking priority within clinical agendas. In relation to workplace culture, it was evident that engaging and assessing patients about potential or experienced sexual concerns were not embedded within organisational expectations of routine practice for HPs. HPs explained that they had no motive for asking about sexual concerns (Krouwel et al., 2020), that sexual concerns were considered supplementary to clinical agendas (Almont et al., 2019), and some HPs indicated a sense of fear about what other colleagues might think about incorporating sexual support as part of routine care (Wazqar, 2020). Furthermore, there was a lack of patient sexual wellbeing information resources available within clinical settings to support communication (Bedell et al., 2017).

Equipping HPs and enabling patients to discuss sexual challenges in cancer care could enhance delivery of sexual support

This theme is presented as two sub-themes to highlight facilitators to provision of sexual support — (i) equipping the HP to deliver sexual support in cancer care, (ii) enabling patients to lead the consultation agenda.

i] Equipping the HP to delivery sexual support in cancer care

Equipping HPs through the provision of education and training (Krouwel et al., 2020), access to supportive patient resources (Williams et al., 2017) and knowledge and access to relevant referral pathways for patients with more complex sexual concerns (Williams et al., 2017) could enhance the provision of sexual support in cancer care. The provision of HP education on sexual concerns after cancer although considered generally lacking (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Canzona et al., 2018; Reese et al., 2017a; Wazqar, 2020), when available improved HPs confidence to provide sexual support (Bedell et al., 2017; Krouwel et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2017). One study highlighted the utility of previous training when it identified that oncologists with more self-stated knowledge discussed sexual function more often (p = 0.002) (Krouwel et al., 2020); however, many of those participants (75.8%, n = 91) indicated a desire for further training as the training received was not specific to oncology. HPs require clear medical guidance related to addressing patient and partner sexual concerns after cancer to equip them to address presenting issues (Canzona et al., 2018; Reese et al., 2017a). Developing communication strategies also helped HPs to provide tailored sexual support conversations. Strategies included a proactive approach to sexual support conversations, active listening, the use of a repertoire of questions or statements to open sexual support conversations and elicit specific concerns (Canzona et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2017), appropriate use of humour (Williams et al., 2017) and developing a good rapport with the patient (Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Reese et al., 2017a; Williams et al., 2017). HPs who felt more confident and those with previous positive experiences of providing sexual support were noted as more likely to provide sexual support (Ahn & Kim, 2020; Reese et al., 2017a).

Providing HPs with supportive patient resources helped them to engage patients (Williams et al., 2017). Two studies identified the need for well-established healthcare systems of care to enable HPs to provide sexual support (Krouwel et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2017). Such systems should include documented and accessible referral pathways for HPs to refer patients to in order to address more complex sexual concerns and ensure continuity of care (Williams et al., 2017). While referral systems can be a facilitator to delivery of sexual support, in others, it was identified as a potential barrier, as they could facilitate HPs to side-step sexual support conversations, passing the responsibility to another colleague (Williams et al., 2017).

ii] Enabling patients to lead the consultation agenda

Regardless of the HP role to provide the patient with information on disease and treatment effects, HPs stated that the provision of sexual support was easier and more likely to occur if patients introduced the topic (Canzona et al., 2018; Maree & Fitch, 2019; Reese et al., 2017a; Williams et al., 2017). One qualitative study of 7 medical oncologists and 4 advanced practice nurses reported the importance of patient education to enable patients to feel able to raise the topic, access sexual support and this would likely prove helpful to change the culture of sexual support provision within cancer care (Reese et al., 2017a).

Discussion

Despite the ongoing expansion of studies within the past 5-years focusing on HP-led sexual support in cancer care, disconcertingly, there remains a clear lack of routine HP-led sexual support in cancer care. What is even more perturbing is this review predominantly reflects views of nurses working with gynaecological and breast tumours whose patients are often recognised as more likely to receive sexual support (Gilbert et al., 2016). Findings overwhelming concur with previous research in that there is “substantial room for improvement” in the provision of sexual support in cancer care (Reese et al., 2017b). Regardless of the growing body of current research, the key barriers to the provision of sexual support remain and strategies regarded by HPs to facilitate positive change are not mobilised and embedded into routine practice. Although delivery of sexual support is advocated in national (NICE 2020) and international guidelines (Carter et al., 2018), ardent efforts are needed to equip the HP workforce imminently, addressing both barriers and facilitators to ensure that this stalemate is overcome. This is essential to improve patient and partner quality of life and relationship satisfaction during and beyond cancer treatment (Reese et al., 2017a).

This study also unearthed the need for a shift in how HPs conceptualise sexual support to promote sexual wellbeing of patients with cancer and their partners. The current evidence had a predominant HP focus on sexual function (biological and physical) of patients rather than a more expansive and holistic perspective relating to strategies to maximise intimacy and pleasure (Ahn & Kim, 2020; Almont et al., 2019; Annerstedt & Glasdam, 2019; Bedell et al., 2017; Canzona et al., 2018; Krouwel et al., 2020; Reese et al., 2017a). While research into patient and partner sexual challenges after cancer has extended to include psychological and relational elements, little attention has been given to successful strategies used by couples to maintain sexual intimacy in the context of cancer (Benoot et al., 2017; Ussher et al., 2013). Patients and partners after cancer report successful strategies to maintaining sexual intimacy to include touch, kissing, hugging, open and flexible communication, with less heightened focus on sexual function and sexual intercourse (Henkelman et al., 2023; Ussher et al., 2015). While it is possible that studies do not fully report the detail of sexual support provision, the current literature suggests that HP communication with patients does not routinely address non-coital strategies to maintain sexual intimacy. Given patient and partner reported improvements to sexual wellbeing achieved through this wider view of sexuality, HPs should seek to provide information beyond that of sexual function and sexual intercourse (Ussher et al., 2013).

The professional and organisation barriers identified within this review demonstrate little change from findings of earlier reviews of HP-led sexual support in cancer care (O’Connor et al., 2019; Reese et al., 2017b; Vassão et al., 2018). Clearly, there remains a personal discomfort for HPs around the topic which results in HPs either avoiding the provision of sexual support or having a light touch and referring patients to more specialist resources (Williams et al., 2017). Duimering et al.’s (2020) pilot-tiered model of sexual care in a Canadian cancer care setting identified a need to equip HPs in cancer care settings with knowledge and skills to provide routine sexual support to effectively assess and address less complex sexual concerns, with only more complex issues being referred to specialist services. Adopting such a tiered model could potentially support many patients and partners in cancer care to access routine sexual support, requiring only a minority of patients and partners to access more costly specialised services (Duimering et al., 2020).

The theory–practice gap, coined as the discrepancy between knowing what should be done and implementation, is not a new phenomenon within healthcare (O’Connor et al., 2019) and can be responsible for inadequate clinical practice (Greenway et al., 2019; Mortell, 2019). Over the last decades, there have been numerous attempts to equip HPs to initiate the provision of sexual support. Communication models such as PLISSIT (Annon, 1976) and BETTER (Mick et al., 2004) have been in existence for some time but alone have not had the necessary impact to influence clinical practice. Communication tools need to be supported with accessible HP education, supportive resources and referral pathways and embedded within an organisational culture which promotes the provision of sexual support as an integral part of holistic patient-centred care (O’Connor et al., 2019). There have been several educational interventions focusing on promoting the delivery of sexual support, which have demonstrated increases in knowledge and confidence, alongside a positive impact on clinical practice using in-person (Quinn et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2015) and online delivery methods (Bingham et al., 2022a; Cassells et al., 2023; McCaughan et al., 2021; Reese et al., 2021). However, given the small number of participants on each study, conclusions on effectiveness of the interventions should be tempered. Nonetheless, HP educational opportunities should be rigorously evaluated with effective interventions implemented using system-wide implementation science strategies based upon a thorough understanding of context, an assessment of implementation determinants, and an understanding of the mechanisms and processes needed to address them (Mittman, 2017).

This review identified several HP attitudinal barriers warranting explicit attention including the negative bias on the relevance of sexual support for older patients, those in a palliative phase in their illness and non-heterosexual patients. This is compounded by the lack of legitimacy of the topic or low prioritisation of discussing sexual concerns in the clinical environment. These enduring and pervading issues are likely influencing the lack of sexual support within survivorship care. HPs require clarity on these issues through education and policy direction. Planning for and implementation of changes to enhance the frequency and quality of sexual support provision in cancer care is important to engage meaningfully with HPs, patients and partners and ensure that the evidence base is used effectively in context (O’Cathain et al., 2019). To address challenges associated with research to achieve evidence-based practice, it is important to consider the growing recognition and learning from implementation science (Nilsen, 2015). There is an expanding recognition of the need to establish theoretical bases of implementation and strategies to facilitate implementation to promote the systematic uptake of research finding into routine practice to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care (Nilsen, 2015). Within the included studies for this review, such focus and detail were frequently lacking, apart from an implementation process reported by Jung and Kim (2016) who introduced process measures, in the form of a sexual health record with nurses in Korea. They reported significantly higher levels (p < 0.000) of sexual support provided by the nurses in the intervention study arm at 4 weeks post-intervention when compared to those in the treatment as usual group. While this change essentially looks positive, the detail of the sexual support provision is not clear, nor do we know if the change in practice improved patient and partner care. Expectations of improvement in the quality of sexual support must be patient-centred, considering patient preferences, comfort, information and education and access to care (Wong et al., 2020).

Validated tools that can effectively measure the extent of impact of cancer and its treatment on patient and partner sexual wellbeing are lacking (Hoole et al., 2015; Tounkel et al.,. 2022). With this evident gap, future research efforts to develop robust and validated measures should consider improvements, as not only whether the communication and sexual support occurred, but ascertain was this related to specific patient and partner needs and clinical priorities (Reese et al., 2019a). To advance this body of knowledge, other aspects should also be considered, such as feasible ways to measure and report the frequency of sexual support provision and with whom, the type of support (assessment, advice and referral), timing of support provision and content (avoid risk, sexual function, fertility, body image, intimacy) in the context of patient and partner needs could help, alongside equipping HP to provide sexual support, challenge the rhetoric around relevance and legitimacy of the topic.

Many of the challenges to the provision of sexual support identified in this review are not specific to the cancer care context alone but have also been reported in other healthcare contexts including cardiovascular and stroke (O’Connor et al., 2019). Similarly, other studies reported a lack of knowledge and access to training while acknowledging the influence of the physical environment and workplace culture, highlighting the need for change across patient care. That said, changing practice continues to be challenging with evident system-wide barriers as described which need systematically and comprehensively addressed.

Policy Implications

Findings from these 12 studies highlighted five strategies for advancing the provision of HP-led sexual support in cancer care, namely, education and training, assessment tools and guidance, effective referral pathways, supportive resources for patients and supporting policy and guidance.

The provision of sexual support in cancer care is not the role of one HP. There is a clear rationale and opportunities for multi-disciplinary HPs involved across the treatment trajectory who assess and intervene to engage patients in sexual wellbeing discussions (Krouwel et al. 2020; Lynch et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2017). HPs often lack accessibility to theory-based and evidence-based educational resources to equip them to deliver sexual support. Of the available sexual support interventions, many are face-to-face, limiting reach (Bingham et al., 2022b). Therefore, education and training should be accessible to HPs working across cancer care and specific to the impact of cancer and treatment across biopsychosocial aspects of sexuality (Almont et al., 2019) bearing in mind culture and local sensitivities, identifying the HP role to provide sexual support (Maree & Fitch, 2019), providing guidance on sexual support communication (Krouwel et al., 2020) and should provide information on treatments specific to the tumour group (Ahn & Kim, 2020; Reese et al., 2017a). To enhance accessibility to HPs, education and training should be included in pre-registration and post-registration training and within practice settings (Papadopoulou et al., 2019), available in a range of formats, including online and in-person; however, convenience and brevity are critical (Reese et al., 2017a). Within training, HPs should be equipped to facilitate the assessment of sexual concerns (Reese et al., 2017a).

To support HPs providing sexual support as part of routine care, the necessary onward referral services should be in place and communicated with HPs for those patients requiring further support, such as psychosexual or couple counselling (Wazqar, 2020). Furthermore, HP-led sexual support conversations can be supported through the development and free-availability of high-quality, evidence-based supportive resources for patients to augment the HP patient discussion of sexual challenges (Almont et al., 2019; Reese et al., 2017a; Williams et al., 2017). Lastly, HPs require policy and guidance ensuring that minimum standards of care are communicated across multidisciplinary roles (Maree & Fitch, 2019; Reese et al., 2017a). If ardent efforts to implement these improvements are not effective, advocating and empowering patients to proactively initiate sexual wellbeing discussions may be an alternative strategy to opening communication.

Research Recommendations

Of note, conducting this review highlighted a gap pertaining to the detailed reporting of the frequency, content, type, timing and quality of HP-led sexual support in cancer care. To assist future research and synthesis on the provision of sexual support in routine cancer care, studies should provide more details on the content and type of sexual support provided, alongside when and how often support is provided and clearly report on evaluation strategies. Second, research should also enquire about HP discussions with patients beyond that of sexual function to explore discussions about non-coital practices that can improve intimacy and pleasure. Third, future reviews of this topic may warrant inclusion of the patient perception and experience of sexual support provision within scope akin to that of Reese et al. (2017a) to provide further understanding on current sexual support provision being cognisant there can be discrepancies between HPs and patients accounts. Lastly, given the dyadic nature of sexual concern and the lack of partner input into current studies reviewing sexual support provision in cancer care, future studies should seek to incorporate the partners’ views on HP-led provision of sexual support.

Strengths and Limitations

The systematic approach to this review has enhanced the rigor, transparency and robustness of the review. A mix of research methodologies across studies, together with empirical studies from diverse contexts (e.g. USA, Saudi Arabia, Zimbabwe) could limit generalisability of findings, particularly given the taboo nature of sexuality in some cultures. Furthermore, low numbers of some HP role categories and lack of ability to segregate data across roles in some studies prevented subgroup analysis, hence the inability to draw role-specific conclusions provision of HP-led sexual support and barriers/facilitators by HP discipline. Last, there was potential scope, given convenient study populations for biased reporting, which may misrepresent the frequency of HP-led sexual support conversations taking place and underreport the extent of barriers to providing sexual support faced by those HPs who did not participate.

Conclusion

This review identifies little change in the provision of HP-led sexual support over recent years despite the increased research focus on the topic and interventions designed to facilitate change. This review identified barriers, similar to those previously acknowledged that need to be addressed in a co-ordinated and systematic manner to successfully impact the provision of HP-led sexual support across the cancer care trajectory. Key to advancing the provision of HP-led sexual support is improving HPs knowledge and skills to deliver sexual support, equipping HPs with supportive resources and developing referral pathways. The use of process outcome measures, such as frequency and quality of sexual support provision, could support successful intervention implementation. Future studies should seek to report more specifically the frequency, type of sexual support, content and timing of intervention and quality of sexual support provision to provide greater insights into clinical practice and to help to identify specific areas warranting support.

Supplementary Information

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

29 May 2024

The original version of this article was updated to correct the references. “Effective patient-provider…” should be 2017a while “Patient provider communication about sexual concerns…” should be 2017b.

References

Afiyanti, Y. (2017). Attitudes, belief and barriers of Indonesian oncology nurses on providing assistance to overcome sexuality problem. Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 7(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.14710/NMJN.V7I1.15124

Ahn, S. H., & Kim, J. H. (2020). Healthcare professionals’ attitudes and practice of sexual health care: Preliminary study for developing training program. Frontiers in Public Health, 8,559851. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.559851

Almont, T., Farsi, F., Krakowski, I., El Osta, R., Bondil, P., & Huyghe, É. (2019). Sexual health in cancer: The results of a survey exploring practices, attitudes, knowledge, communication and professional interactions in oncology healthcare providers. Supportive Care in Cancer., 27(3), 887–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4376-x

Annerstedt, C. F., & Glasdam, S. (2019). Nursesʼ attitudes towards support for and communication about sexual health—A qualitative study from the perspectives of oncological nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(19), 3556–3566. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14949

Annon, J. S. (1976). The PLISSIT model: A proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioural treatment of sexual problems. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 2(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01614576.1976.11074483

Bedell, S., Manders, D., Kehoe, S., Lea, J., Miller, D., Richardson, D., & Carlson, M. (2017). The opinions and practices of providers toward the sexual issues of cervical cancer patients undergoing treatment. Gynecologic Oncology, 144(3), 586–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.12.022

Benoot, C., Saelaert, M., Hannes, K., & Bilsen, J. (2017). The sexual adjustment process of cancer patients and their partners: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 2059–2083. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0868-2

Bingham, S. L., Semple, C. J., Flannagan, C., & Dunwoody, L. (2022a). Enhancing healthcare professional-led sexual support in cancer care: Acceptability and usability of an eLearning resource and its impact on attitudes towards providing sexual support. Psycho-Oncology, 31(9), 1555–1563.

Bingham, S. L., Semple, C. J., Flannagan, C., & Dunwoody, L. (2022b). Adapting and usability testing of an eLearning resource to enhance healthcare professional provision of sexual support across cancer care. Supportive Care in Cancer, 30(4), 3541–3551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-06798-w

Bober, S. L., & Varela, V. S. (2012). Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: Challenges and intervention. J Clinical Oncology, 30(30), 3712–3719. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7915

Bond, C. B., Jensen, P. T., Groenvold, M., & Johnsen, A. T. (2019). Prevalence and possible predictors of sexual dysfunction and self-reported needs related to the sexual life of advanced cancer patients. Acta Oncologica, 58(5), 769–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2019.1566774

Canzona, M. R., Garcia, D., Fisher, C. L., Raleigh, M., Kalish, V., & Ledford, C. J. (2016). Communication about sexual health with breast cancer survivors: Variation among patient and provider perspectives. Patient Education and Counselling, 99(11), 1814–1820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.019

Canzona, M. R., Ledford, C., Fisher, C. L., Garcia, D., Raleigh, M., & Kalish, V. B. (2018). Clinician barriers to initiating sexual health conversations with breast cancer survivors: The influence of assumptions and situational constraints. Families, Systems and Health: THe Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 36(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000307

Carter, J., Lacchetti, C., Andersen, B. L., Barton, D. L., Bolte, S., Damast, S., Diefenbach, M. A., DuHamel, K., Florendo, J., Ganz, P. A., Goldfarb, S., Hallmeyer, S., Kushner, D. M., & Rowland, J. H. (2018). Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36(5), 492–511.

Cassells, C.V., Semple, C.J., Stothers, S. & Bingham, S.L. (2023) Maximising professional-led sexual wellbeing support in cancer care: Findings from a qualitative process evaluation following healthcare professionals’ engagement with an eLearning resource. Cancer Nursing, Accepted.

Collaço, N., Rivas, C., Matheson, L., Nayoan, J., Wagland, R., Alexis, O., Gavin, A., Glaser, A., & Watson, E. (2018). Prostate cancer and the impact on couples: A qualitative metasynthesis. Supportive Care in Cancer., 26(6), 1703–1713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4134-0

Doolen, J. (2017). Meta-analysis, systematic, and integrative reviews: An overview. Clinical Simulation Nursing, 13(1), 28–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2016.10.003

Downing, A., Wright, P., Hounsome, L., Selby, P., Wilding, S., Watson, E., Wagland, R., Kind, P., Donnelly, D. W., Butcher, H., & Catto, J. W. (2019). Quality of life in men living with advanced and localised prostate cancer in the UK: A population-based study. The Lancet Oncology, 20(3), 436–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30780-0

Duimering, A., Walker, L. M., Turner, J., Andrews-Lepine, E., Driga, A., Ayume, A., Robinson, J. W., & Wiebe, E. (2020). Quality improvement in sexual health care for oncology patients: A Canadian multidisciplinary clinic experience. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(5), 2195–2203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05040-4

Ferreira, S. M. D. A., Gozzo, T. D. O., Panobianco, M. S., Santos, M. A. D., & Almeida, A. M. D. (2015). Barriers for the inclusion of sexuality in nursing care for women with gynecological and breast cancer: Perspective of professionals. Revista Latino-Americana De Enfermagem, 23, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-1169.3602.2528

Gilbert, E., Perz, J., & Ussher, J. M. (2016). Talking about sex with health professionals: The experience of people with cancer and their partners. European Journal of Cancer Care, 25(2), 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12216

Greenway, K., Graham, B., & Walthall, H. (2019). What is a theory-practice gap? An exploration of the concept. Nurse Education and Practice, 34, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.10.005

Grondhuis Palacios, L. A., den Ouden, M. E., den Oudsten, B. L., Putter, H., Pelger, R. C., & Elzevier, H. W. (2019). Treatment-related sexual side effects from the perspective of partners of men with prostate cancer. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 45(5), 440–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2018.1549636

Henkelman, M. S., Toivonen, K. I., Tay, J., Beattie, S., & Walker, L. M. (2023). Patient-reported disease-specific concerns relating to sexuality in multiple myeloma. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology Research and Practice, 5(4), 112. https://doi.org/10.1097/OR9.0000000000000112

Hoole, J., Kanatas, A., Calvert, A., Rogers, S. N., Smith, A. B., & Mitchell, D. A. (2015). Validated questionnaires on intimacy in patients who have had cancer. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 53(7), 584–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.05.003

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., & Rousseau, M. C. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

Jonsdottir, J. I., Zoëga, S., Saevarsdottir, T., Sverrisdottir, A., Thorsdottir, T., Einarsson, G. V., Gunnarsdottir, S., & Fridriksdottir, N. (2016). Changes in attitudes, practices and barriers among oncology healthcare professionals regarding sexual health care: Outcomes from a 2-year educational intervention at a University Hospital. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 21, 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2015.12.004

Kim, S., Kang, H. S., & Kim, J. H. (2011). A sexual health care attitude scale for nurses: Development and psychometric evaluation. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(12), 1522–1532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.06.008

Jung, D., & Kim, J. H. (2016). Effects of a sexual health care nursing record on the attitudes and practice of oncology nurses. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 9, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2016.06.001

Krouwel, E. M., Albers, L. F., Nicolai, M. P. J., Putter, H., Osanto, S., Pelger, R. C. M., & Elzevier, H. W. (2020). Discussing sexual health in the medical oncologist’s practice: Exploring current practice and challenges. Journal of Cancer Education, 35(6), 1072–1088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01559-6

Krouwel, E. M., Nicolai, M. P. J., Van Steijn-van Tol, A. Q. M. J., Putter, H., Osanto, S., Pelger, R. C. M., & Elzevier, H. W. (2015). Addressing changed sexual functioning in cancer patients: A cross-sectional survey among Dutch oncology nurses. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19(6), 707–715.

Lee, L., Jacklin, M., & Boyer, C. (2012). Giving staff confidence to discuss sexual concerns with patients. Cancer Nursing Practice, 11(2), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.7748/cnp2012.03.11.2.28.c8988

Lynch, O., O’Donovan, A., & Murphy, P. J. (2019). Addressing treatment-related sexual side effects among cancer patients: Sub-optimal practice in radiation therapy. European Journal of Cancer Care, 28(3):e13006 https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13006

Magnan, M. A., Reynolds, K. E., & Galvin, E. A. (2005). Barriers to addressing patient sexuality in nursing practice. Medsurg Nursing, 14(5)

Maiorino, M. I., Chiodini, P., Bellastella, G., Giugliano, D., & Esposito, K. (2016). Sexual dysfunction in women with cancer: A systematic review with meta-analysis of studies using the Female Sexual Function Index. Endocrine, 54(2), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-015-0812-6

Maree, J., & Fitch, M. I. (2019). Holding conversations with cancer patients about sexuality: Perspectives from Canadian and African healthcare professionals. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 29(1), 64–69.

McCaughan, E., Flannagan, C., Bingham, S. L., Brady, N., Parahoo, K., Connaghan, J., Maguire, R., Steele, M., Thompson, S., Jain, S., Kirby, M., & O’Connor, S. R. (2021). Effects of a brief e-learning resource on sexual attitudes and beliefs of healthcare professionals working in prostate cancer care: A single arm pre and post-test study. Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), E10045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910045

McLeod, D. L., & Hamilton, J. (2013). Sex talk and cancer: Who is asking. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal., 23(3), 197–207. Available at: http://www.canadianoncologynursingjournal.com/index.php/conj/article/view/96

Merriam, S. B., & DiNardo, D. (2018). Talking sex with cancer survivors: Effects of an educational workshop for primary care providers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(2), 353.

Mick, J., Hughes, M., & Cohen, M. Z. (2004). Using the BETTER model to assess sexuality. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 8(1), 84–86. https://doi.org/10.1188/04.CJON.84-86

Mittman BS. Implementation science in health care In: Brownson, R.C., Colditz, G.A. and Proctor, E.K. (2017). Eds. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. England. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190683214.001.0001

Moore, A., Higgins, A., & Sharek, D. (2013). Barriers and facilitators for oncology nurses discussing sexual issues with men diagnosed with testicular cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17(4), 416–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2012.11.008

Mortell, M. (2019). Is there a theory practice ethics gap? A patient safety case study. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 10, 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2018.12.002

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (January 2020). Colorectal Cancer. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng151. [Accessed: 1 March 23].

Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10, 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

O’Connor, S. R., Connaghan, J., Maguire, R., Kotronoulas, G., Flannagan, C., Jain, S., Brady, N., & McCaughan, E. (2019). Healthcare professional perceived barriers and facilitators to discussing sexual wellbeing with patients after diagnosis of chronic illness: A mixed-methods evidence synthesis. Patient Education and Counselling, 102(5), 850–863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.12.015

O’Cathain, A., Croot, L., Duncan, E., Rousseau, N., Sworn, K., Turner, K. M., Yardley, L., & Hoddinott, P. (2019). Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. British Medical Journal Open, 9(8), e029954. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029954

Oskay, U., Can, G., & Basgol, S. (2014). Discussing sexuality with cancer patients: Oncology nurses attitudes and views. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 15(17), 7321–7326. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.17.7321

Papadopoulou, C., Sime, C., Rooney, K., & Kotronoulas, G. (2019). Sexual health care provision in cancer nursing care: A systematic review on the state of evidence and deriving international competencies chart for cancer nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 100, 103405.

Quinn, G. P., Bowman Curci, M., Reich, R. R., Gwede, C. K., Meade, C. D., ENRICH/ECHO Working Group, & Vadaparampil, S. T. (2019). Impact of a web-based reproductive health training program: ENRICH (Educating Nurses about Reproductive Issues in Cancer Healthcare). Psycho-Oncology, 28(5), 1096–1101. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5063

Reese, J. B., Sorice, K., Beach, M. C., Porter, L. S., Tulsky, J. A., Daly, M. B., & Lepore, S. J. (2017b). Patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in cancer: A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 11(2), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0577-9

Reese, J. B., Beach, M. C., Smith, K. C., Bantug, E. T., Casale, K. E., Porter, L. S., Bober, S. L., Tulsky, J. A., Daly, M. B., & Lepore, S. J. (2017a). Effective patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in breast cancer: A qualitative study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(10), 3199–3207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3729-1

Reese, J. B., Lepore, S. J., Daly, M. B., Handorf, E., Sorice, K. A., Porter, L. S., Tulsky, J. A., & Beach, M. C. (2019a). A brief intervention to enhance breast cancer clinicians’ communication about sexual health: Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary outcomes. Psycho-Oncology, 28(4), 872–879. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5036

Reese, J. B., Sorice, K., Lepore, S. J., Daly, M. B., Tulsky, J. A., & Beach, M. C. (2019b). Patient-clinician communication about sexual health in breast cancer: A mixed-methods analysis of clinic dialogue. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(3), 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.10.003

Reese, J. B., Zimmaro, L. A., Bober, S. L., Sorice, K., Handorf, E., Wittenberg, E., El-Jawahri, A., Beach, M. C., Wolff, A. C., Daly, M. B., & Izquierdo, B. (2021). Mobile technology-based (mLearning) Intervention to enhance breast cancer clinicians’ communication about sexual health: A pilot trial. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 19(10), 1133–1140. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2021.7032

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodology, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Tounkel, I., Nalubola, S., Schulz, A., & Lakhi, N. (2022). Sexual health screening for gynecologic and breast cancer survivors: A review and critical analysis of validated screening tools. Sexual Medicine, 10(2), 100498–100498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2022.100498

Traa, M. J., Orsini, R. G., Oudsten, B. L. D., Vries, J. D., Roukema, J. A., Bosman, S. J., Dudink, R. L., & Rutten, H. J. (2014). Measuring the health-related quality of life and sexual functioning of patients with rectal cancer: Does type of treatment matter? International Journal of Cancer, 134(4), 979–987. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28430

Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., Gilbert, E., Australian Cancer and Sexuality Study Team. (2015). Perceived causes and consequences of sexual changes after cancer for women and men: A mixed method study. BMC Cancer, 15, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1243-8

Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., Gilbert, E., Wong, W. T., & Hobbs, K. (2013). Renegotiating sex and intimacy after cancer: Resisting the coital imperative. Cancer Nursing, 36(6), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182759e21

Vasilenko, S. A. (2022). Sexual behavior and health from adolescence to adulthood: Illustrative examples of 25 years of research from Add Health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 71(6), S24–S31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.08.014

Vassão, F. V., Barbosa, L. R., Moraes, G. M. D., & Domenico, E. B. L. D. (2018). Approach to sexuality in the care of cancer patients: Barriers and strategies. Acta Paulista De Enfermagem, 31, 564–571. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0194201800078

Vermeer, W. M., Bakker, R. M., Kenter, G. G., Stiggelbout, A. M., & Ter Kuile, M. M. (2016). Cervical cancer survivors’ and partners’ experiences with sexual dysfunction and psychosexual support. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(4), 1679–1687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2925-0

Wang, L. Y., Pierdomenico, A., Lefkowitz, A., & Brandt, R. (2015). Female sexual health training for oncology providers: New applications. Sexual Medicine, 3(3), 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/sm2.66

Wazqar, D. Y. (2020). Sexual health care in cancer patients: A survey of healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes and barriers. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(21–22), 4239–4247. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15459

Wendt, C. (2017). Perception and assessment of verbal and written information on sex and relationships after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Journal of Cancer Education, 32(4), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-016-1054-x

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Williams, N. F., Hauck, Y. L., & Bosco, A. M. (2017). Nurses’ perceptions of providing psychosexual care for women experiencing gynaecological cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 30, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2017.07.006

Wong, E., Mavondo, F., & Fisher, J. (2020). Patient feedback to improve quality of patient-centred care in public hospitals: A systematic review of the evidence. BMC Health Services Research, 20, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05383-3

Zeng, Y. C., Li, Q., Wang, N., Ching, S. S., & Loke, A. Y. (2011). Chinese nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care in cancer patients. Cancer Nursing, 34(2), E14–E20. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f04b02

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SLB: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, validation, writing — original draft; CC: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, validation, writing — original draft; CJS: methodology, formal analysis, supervision, validation, writing — review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bingham, S.L., Cassells, C.V. & Semple, C.J. Factors Influencing the Provision of Healthcare Professional-Led Sexual Support to Patients with Cancer and Their Partners: An Integrative Review of Studies from 2017 to 2022. Sex Res Soc Policy (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-024-00974-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-024-00974-9