Abstract

Introduction

Older lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans (LGBT+) adults have been mainly studied in relation to stigma and mental and physical disorders. Understanding their satisfaction with life, along with their generative expression, is crucial in building healthy aging. This study examined the satisfaction with life of Spanish older LGBT+ adults, considering the role of generativity.

Methods

Data were gathered online; 141 Spanish LGBT+ people completed the Loyola Generativity Scale (LGS), Generative Behaviour Checklist (GBC), and Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). Data were analysed through descriptive, nonparametric tests, and correlational statistics. A multivariable linear regression analysis was conducted to determine the relationship between the SWLS and the other scales, including social and demographic variables as covariates.

Results

Satisfaction with life and generativity are positively associated to (i) disclosure in all areas of life, (ii) perceived support in the disclosure process, (iii) (daily) participation in social activities, and (iv) higher in women, (v) in those who have a partner, and (vi) who have children. The multivariable regression model explained 32.6% of the variance in SWLS. The SWLS increased with generativity confidence and behaviours of collaboration and care.

Conclusions

Satisfaction with life and generativity are promoted by disclosure in all areas of life, and perceived support in the disclosure process.

Policy Implications

Social policies and programs should (i) encourage LGBT+ individuals’ disclosure and support them in this process, probably by creating safe and supportive environments; (ii) promote LGBT+ older adults’ social participation, namely in terms of volunteering and mentoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Understanding the features of ageing well in different populations, groups, and communities is paramount; according to the paradigm of healthy ageing, no one should be left behind (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). Most literature on individuals self-identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans (LGBT+) has focused on adolescents and young adults (Rosati et al., 2020). Literature on middle aged and older LGBT+ adults has researched stigma, discrimination and prejudice, violence, mental disorders, psychological distress, and loneliness (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014; Henry et al., 2021; Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al., 2022). Whilst the stressors impacting the aging process of LGBT+ individuals are being addressed, less is known about their resilience and satisfaction with life (Bower et al., 2021; de Vries, 2015; Emlet & Harris, 2020). Thus, this study aimed to contribute to a more positive perspective on the aging process amongst LGBT+ individuals, by focusing satisfaction with life, and generativity (Casado et al., 2023).

Overall, literature tends to consider that older LGBT+ includes adults over aged of 50+ years old (Choi & Meyer, 2016; Fredriksen-Goldsen & de Vries, 2019) instead of 65+ . This is because LGBT+ individuals present a greater risk of physical and mental illnesses, which may result in a lower quality of life and premature death (Bower et al., 2021; von Humboldt et al., 2020). Individuals may experience compressed life cycles that comprise the anticipation of developmental processes (Werner-Lin, 2008), as reported for other vulnerable older groups, such as individuals with degenerative diseases (Oliveira et al., 2022).

Satisfaction with life refers to the overall positive cognitive judgement of one’s life, a desirable attainment at all stages of life (Diener et al., 1985; Emerson et al., 2017). In older adults, satisfaction with life is a key component of quality of life and aging well (WHO, 2020), and it has been widely studied in different populations (O’Neil-Pirozzi et al., 2022). Satisfaction with life has been correlated to generativity, considering a bi-directional association (Becchetti & Bellucci, 2021; Grossman & Gruenewald, 2020; Sunderman et al., 2022). It has been suggested that generativity is a significant resilience factor for older LGBT+ adults (Bower et al., 2021; Emlet & Harris, 2020; Emlet et al., 2010). Erikson (1963) introduced the concept of generativity to describe a desire to support and guide younger generations (Erikson, 1963). Erikson considered generativity as a midlife task; however, further research considered that generativity could take place in all stages of adult life (McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992; McAdams et al., 1993). Generativity can be achieved in various social domains such as in the family, workplace, or social activities (Bush & Hofer, 2022). Research in generativity has been focused on the concerns regarding the contributions of and the behaviours that entail generative acts (McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992). In relation to LGBT+ individuals, some studies have suggested that older members of the LGBT+ community seek meaning from the marginalisation of their past, so they can influence (be generative) future efforts to continue their work and advocate for social equality, thus pursuing generativity (Casado et al., 2023; Roseborough, 2004). Although there is a significant body of literature on generativity and satisfaction with life, most studies do not acknowledge/ask participants’ self-identification in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity. In fact, few scholars have studied the concept of generativity regarding LGBT+ identities (Grabovac et al., 2019; Miller-McLemore, 2004).

The social context where people live and age are key determinants of life satisfaction in old age (Fredriksen-Goldsen & de Vries, 2015). In Spain, those currently 50+ years old were born during a dictatorship that lasted until 1975, which severely criminalised homosexuality and oppressed diversity in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity (Amigo-Ventureira et al., 2022; López-Sáez et al., 2022). Following the transition to democracy, Spain has in recent decades advanced in the protection of citizens’ rights inclusive of sexual orientation and gender identities (Amigo-Ventureira et al., 2022; López-Sáez et al., 2022). LGBT+ individuals in Spain currently benefit from an unprecedented degree of legal support and formal inclusion (Casado et al., 2023); the country ranks in the top 10 of European nations with respect to human rights and equality for LGBT+ people (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association [ILGA], 2021). Despite the progress in legislation and the greater public, social attitudes towards LGBT+ remains an issue (Amigo-Ventureira et al., 2022; López-Sáez et al., 2022). Nevertheless, Spain is amongst the EU countries with the best legislation on LGBT+ rights and is in a good position to progress and inspire other countries and world regions.

This study examined the satisfaction with life of Spanish older LGBT+ adults (50+ years) by considering the role of generativity (concerns and behaviours) and their association with sociodemographic, disclosure process, and social participation variables. The results can help to inform policies, programmes, and interventions for older LGBT+ adults.

Methods

This study is part of a larger project entitled “Generativity, intended legacies, social participation and life satisfaction in LGBT+ older adults”, which received approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of the Balearic Islands [162CER20]. In this study, an observational, cross-section, and descriptive correlational design was used to address generativity and life satisfaction.

Instrument

An anonymous self-report questionnaire was used to collect data. The questionnaire included four sections.

-

(A)

Social and demographic data were collected, comprising sexual orientation (lesbian, gay, bisexual, heterosexual, other orientation), gender identity (cis woman, cis man, trans woman, trans man, other identity), age, marital status, residence area, years of formal education, children (y/n) and grandchildren (y/n), employment status, and household size. Participants were asked about disclosure (yes; yes, but not in all the areas of my life; no), age of disclosure, and perceptions of support in the process of disclosure (yes, all support I needed; yes, although less than I would like; not much/no). In addition, participants were asked about participation in social activities (such as activism, volunteerism, and advocacy): yes/no; if yes, frequency (occasionally, 1–2 times per week, daily).

-

(B)

The LGS — Loyola Generative Scale (McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992; Spanish version by Villar et al., 2013) assesses adult population concerns to contribute to the well-being of the younger generations. It consists of 20 statements, each one rated 0 (never)‚ 1 (occasionally)‚ 2 (fairly often), or 3 (very often or nearly always). A total score is obtained by summing the grading of all items. It comprises two factors (McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992; Villar et al., 2013): positive generativity (14 items; positively worded statements) and generative doubts (6 items; negatively phrased items). The Cronbach alpha for the original version was 0.83 (McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992); in the Spanish version was 0.89 (Villar et al., 2013). In this study we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA); a two-factor model emerged, comprising 14 items which account for a total of variance of 45.1% (Appendix Table 6). Factor 1 (positive generativity) included 10 items and factor 2 (named “generative confidence” instead of generative doubts, since the items were reversed in our study) comprises four items (Appendix Table 6). Higher scores express greater generative concerns; lower scores indicate low capacity to influence other people. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was global = 0.77, positive generativity = 0.82, and generative confidence = 0.51.

-

(C)

The GBC — Generative Behaviour Checklist (McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992; Spanish version by Villar et al., 2013) measures everyday actions suggestive of generativity. It is a self-reported instrument with a 3-point Likert scale, in which the participants respond to each act by identifying how often during the previous 2 months they had performed the given action (0 = have not participated, 1 = participated in it once, and 2 = more than once). The Spanish version (Villar et al., 2013) comprises 29 items; a global score is obtained by summing the responses, with higher scores indicating more generative acts. In this study we conducted an EFA from which a two-factor model emerged, comprising 20 items and accounting for a total of variance of 41.67% (Appendix Table 7). Factor 1 was named “volunteering and donating” (11 items) involving acts that imply contributing to others (relatives or community members) by personal means or via institutions and factor 2 “collaboration and care” (nine items) that involves the personal care of someone (close relatives or community members) or something. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was global = 0.88, volunteering and donating = 0.86, and collaboration and care = 0.77.

-

(D)

The SWLS — Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985; Spanish version by Pons et al., 2000) provides an indicator of subjective well-being, referring to positive aspects of life. It consists of 5 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. The original version has a high internal consistency (α = 0.83), as well as the Spanish version (α = 0.82). A global score is obtained by summing responses to all five items. Scores range from 5 to 25, where higher scores indicate higher satisfaction with life.

Data Collection

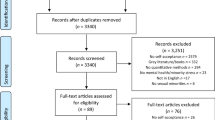

The recruitment was conducted with the collaboration of the Federación Estatal LGTBI+ (FELGTBI+) [State Federation] that disseminated the study by sharing the online survey amongst 57 NGOs (non-governmental organisations). The NGOs were asked to send an email invitation to their members. The email invitation comprised information about the project, the researchers and contact information, the inclusion criteria (self-identification as LGBT+ , aged 50+ years, resident in Spain), and the link to the survey. Those willing to participate were asked to open the provided link, which directed them to a welcome page containing information about the study and the informed consent. After providing their informed consent, the participants accessed the survey, which took around 15 min to complete. Data was gathered between October 2020 and December 2021, and two email reminders were sent to the FELGTBI+ , which resent it to the NGOs, to increase the response rate.

Data Analysis

Frequency and percentages were calculated for the social and demographic categorical variables; mean (M) with standard deviation (SD) were used for the continuous variables. For the continuous variable, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (p < 0.05) test and the residuals’ normality were not verified (by visual inspection of Q-Q plots). Thus, two non-parametric tests were used for statistical differences between groups: the Mann-Whitney test (two groups) and the Kruskal-Wallis test (more than 2 groups). The correlation between the continuous variable and scales was calculated using Spearman’s rank correlation. A multivariable linear regression was performed to determine the relationship between the SWLS and the other scales (LGS and GBC) including the social and demographic variables as covariates. The normality of the residuals was verified by visual inspection of the Q-Q plot, and the Omnibus test was performed to compare the fitted model against the intercept-only model. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 28 software package. A p-value < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 141 participants (Table 1), mean age 58.59 ± 5.80 years, ranging from 51 to 80 years. In terms of gender identity, 61.7% self-identified as cis men, 28.3% as cis women, 5.7% as trans women, and 4.3% as non-binary. Regarding sexual orientation, 63.6% self-identified as gay, 27.9% as lesbian, 7.1% as bisexual, and 1.4% as heterosexual. Of the participants, 76.6% have a college degree, and 67.4% are currently employed. Approximately 45.4% are married or in a civil union, and 43.3% are single; 27% have children and 10.6% have grandchildren. The household size mean is 1.88 ± 0.81. Two of the participants did not disclose their sexual orientation and/or gender identity; the remaining did disclose, although 18.4% responded “not in all” areas of their lives. The mean age of disclosure was 28.76 ± 11.58 years; 52.2% perceived support (yes) in the process of disclosure, whilst 24.1% answered “yes, although less than I would like”, and 22.7% did not perceived support.

SWLS and Generativity (LGS, GBC)

For SWLS, LGS, and GBC, we calculated the means and SD and determined if there were significant differences for demographic variables, disclosure of sexual orientation and/or gender identity, perceived support in the disclosure process, and frequency/participation in social activities. For the SWLS, the mean was 19.23 ± 4.61 (out of 25). The significant differences are shown in Table 2. Higher levels of SWL were found in LGBT+ adults with children, married/civil union, and who had support (answer “yes”) in the disclosure process. SWLS was positively and significantly correlated with the household size.

The mean for the LGS-total was 28.6 ± 5.4 (out of 42), the mean for LGS-positive generativity was 20.0 ± 4.6 (out of 30), and the mean for LGS-generative confidence was 8.6 ± 2.1 (out of 12). The significant differences are shown in Table 3. Significantly higher scores in LGS-total and LGS-positive generativity were obtained by the participants who have disclosed (answered yes) their sexual orientation and/or gender identity and those with a daily frequency of participation in social activities. Significantly higher scores in LGS-total and LGS-generative confidence were found in those who participated in social activities.

The mean for GBC-total was 26.0 ± 8.7 (out of 40), the mean for GBC-volunteering and donate was 13.23 ± 6.01 (out of 22), and the mean for GBC-collaboration and care was 12.79 ± 3.83 (out of 18). Significant differences (Table 4) were found. GBC-total, GBC-volunteering and donating, and GBC-collaboration and care were significantly higher for those participating daily in social activities; GBC-total and GBC-collaboration and care were significantly lower in single participants, and higher in women (cis and trans), in those with children, and those who disclosure (answered yes) their sexual orientation and/or gender identity; and GBC-collaboration and care was significantly lower in gay men and retired participants. The age of disclosure was significantly negatively correlated to GBC-total, and the household size was significantly positively correlated to GBS-total and GBC-collaboration and care.

A multivariable regression model for the SWLS was performed (Table 5). Overall, the model explained 32.6% of the variance in SWLS and was significantly different from the intercept-only model (Omnibus test: χ2(7) = 56.223, p < 0.001). SWLS increased with age, LGS-generative confidence, GBC-collaboration and care, and the household size. Moreover, SWL increased with the perceived support in the disclosure process (the yes category in comparison to the “yes, but not in all areas of my life” and “not much/no”). Other variables were considered for the multivariable linear regression model but the results were non-significant (p > 0.05).

Discussion

This study examined the satisfaction with life of Spanish older LGBT+ adults (50+ years) by considering the role of generativity (concerns and behaviours) and their link to social and demographic variables.

The regression model showed that SWLS increases with LGS-generative confidence, GBC-collaboration and care, household size, and perceived support in the disclosure process (yes category). SWLS was 19.23 ± 4.61 (out of 25) and significantly higher in those who have children, are married or have a partner, and positively significantly correlated with the household size. SWLS was higher in those who perceived support in the disclosure process (answered yes). Our results are consistent with other studies that suggested the contribution of generativity to well-being and satisfaction with life in several population groups (Becchetti & Bellucci, 2021; Bower et al., 2021; Grossman & Gruenewald, 2020; Pons et al., 2000; Serrat et al., 2018; Sunderman et al., 2022).

Three key findings are relevant to our sample of Spanish older LGBT+ adults. First, SWL and generativity (particularly generative confidence and behaviours of contributing and care) are positively associated to disclosure in all areas of life and perceived support in the disclosure process. In fact, the concealment of sexual identity and/or gender identity has been associated with negative consequences, namely worse mental and physical health, less relationship satisfaction, social isolation, and loneliness (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014; Henry et al., 2021; Mohr & Fassinger, 2006; Morris et al., 2001; Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al., 2022). In addition, the process of disclosure comprises an important decision and journey for LGBT+ persons, particularly those currently aged 50+ years of age in Spain, since they have lived through a historical period in which stigma and discrimination were prevalent and social acceptance was low. The support in the process has shown to be a strong predictor of self-esteem (Snapp et al., 2015), which is crucial for generative confidence. Engagement in generative behaviours, in particular those of closer personal nature (such as contributing and care), may be difficult for someone who has not disclosure his/her sexual orientation and/or gender identity, who may fear exposing their identity, or somehow reveal the identity struggle they may go through.

Second, SWLS and generativity (generative confidence and behaviours of contributing and care) are associated with daily participation in social activities. Generativity is a contribution to further generations, in which the participation in social activities play a relevant role (Casado et al., 2023). The type of social participation was not asked in our survey; thus, we do not know in what activities the participants are involved in. Previous literature has shown that the participation in LGBT+ activism is related to meaning in live and community connection (Szymanski et al., 2021). In addition, research supports that generativity is enhanced by the participation and engagement in society, including formal (by volunteering in charities or activism/advocacy) and informal (such as helping neighbours or co-workers, or caring for relatives) involvement (Pinazo-Hernandis et al., 2022). Our participants who are daily involved in social activities experience higher generativity and satisfaction with life, which has been associated to healthy and active aging (WHO, 2020).

Third, SWLS and GBC-collaboration and care are higher in those who have a partner, have children, and have higher household sizes. Families are a key factor in a person’s satisfaction with life and generativity. Families of choice have been linked to the LGBT+ community (Jones-Wild, 2012). In this study, it seems that better satisfaction with life and more generativity are linked to having a family consisting of living with a partner and having children. This is probably a new scenario that is emerging due to better legislation enforcing equality and rights and due to increasing social acceptance (Casado et al., 2023). Nevertheless, some results are transversal to studies on generativity, namely women are more generative than men (Karacan, 2014; Villar et al., 2021); in our study, both cis and trans women have higher generativity. Generativity is more frequent and higher amongst members of a household, with members caring for each other, in particular parents caring for children (Karacan, 2014; Villar et al., 2021).

Our results present important implications. Community and organisations (LGBT+ and social) could develop programmes and measures that support disclosure in all areas of life, to promote generativity and satisfaction with life. In addition, LGBT+ individuals should ponder their involvement in social activities that are relevant for generativity, and therefore to satisfaction with life. Having a partner and children improves satisfaction with life and generativity; therefore, legislative measures, as well as community acceptation and normalisation, should continue to support rights for all families.

Limitations and Perspectives of the Research Study

This study has limitations. First, a larger sample would allow comparisons within the LGBT+ community (for instance, to compare lesbian versus gay versus trans gender individuals). Second, the mean age in our sample is 58.59 years old. Future studies need to focus LGBT+ aged 70+ years old, since literature about those aged 50 to 69 years is increasing, but much less is known about further ages. Third, our sample mostly consisted of cis gay men and lesbians; the inclusion of more trans (in particular trans men, who are missing from our sample), bisexual and non-binary participants, would have been valuable. Despite our efforts to recruit a larger sample, reaching the 50+ year-old group within the LGBT+ population was challenging; this was noted in previous studies (Frediksen-Goldsen & de Vries, 2019). Fourth, the data collection procedures were based on an online survey disseminated with the support of FELGTBI+ . This procedure is prone to two biases: the inclusion of participants who are involved in organisations and the exclusion of those who do not have or use Internet. Further studies need to adopt recruitment procedures that allow to reach these participants; using a snow-ball procedure and face-to-face interviews may be more effective in reaching LGBT+ participants who have not disclosure and are not engaged in organisations. Fifth, our questionnaire was short and did not include questions on friends and chosen families, children and grandchildren, or type of social activities participants are engaged in. Future studies can delve deeper into these topics.

Conclusions

The results of our study suggest that satisfaction with life is positively associated to generative confidence and generative behaviours of collaboration and care. Satisfaction with life and generativity in Spanish older LGBT+ adults are positively associated to disclosure in all areas of life and perceived support in the disclosure process, associated with daily/participation in social activities. They are also higher in those who have a partner, children, and higher household sizes. Satisfaction with life as well as generativity are relevant to the person, families, and society. Social programmes and policies can use this knowledge to promote healthy aging in older LGBT+ adults.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Amigo-Ventureira, A., DePalma, R., & Durán-Bouza, M. (2022). Homophobia and transphobia among Spanish practicing and future teachers. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 17(3), 277–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2022.2035290

Becchetti, L., & Bellucci, D. (2021). Generativity, aging and subjective well-being. International Review of Economy, 68(2), 141–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-020-00358-6

Bower, K., Lewis, D., Bermúdez, J. M., & Singh, A. (2021). Narratives of generativity and resilience among LGBT older adults: Leaving positive legacies despite social stigma and collective trauma. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(2), 230–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1648082

Busch, H., & Hofer, J. (2022). Recalled positive influences within life-story interviews and self-reported generative concern in German older adults: The moderating role of extraversion. Journal of Adult Development, 29, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-021-09385-1

Casado, T., Tavares, J., Guerra, S., & Sousa, L. (2023). Leaving a mark and passing the torch: Intended legacies of older lesbian and gay Spanish activists. Journal of Homosexuality, 70(10), 2035–2049. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2022.2048165

Choi, S., & Meyer, I. (2016). LGBT aging: A review of research findings, needs, and policy implications. UCLA: The Williams Institute. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/03r9x8t3#author

de Vries, B. (2015). Stigma and LGBT aging: Negative and positive marginality. In N. A. Orel & C. A. Fruhauf (Eds.), The lives of LGBT older adults: Understanding challenges and resilience (pp. 55–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14436-003

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Emerson, S. D., Guhn, M., & Gadermann, A. M. (2017). Measurement invariance of the Satisfaction with Life Scale: Reviewing three decades of research. Quality of Life Research, 26, 2251–2264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1552-2

Emlet, C., & Harris, L. (2020). Giving back is receiving: The role of generativity in successful aging among HIV-positive older adults. Journal of Aging & Health, 32(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264318804320

Emlet, C., Tozay, S., & Raveis, V. (2010). “I’m not going to die from the AIDS”: Resilience in aging with HIV disease. The Gerontologist, 51(1), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq060

Erikson, E. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). Norton.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., & de Vries, B. (2019). Global aging with pride: International perspectives on LGBT aging. International Journal of Human Development, 88(4), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415019837648

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Simoni, J. M., Kim, H.-J., Lehavot, K., Walters, K. L., Yang, J., Hoy-Ellis, C. P., & Muraco, A. (2014). The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000030

Grabovac, I., Smith, L., McDermott, D. T., Stefanac, S., Yang, L., Veronese, N., & Jackson, S. E. (2019). Well-being among older gay and bisexual men and women in England: A cross-sectional population study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(9), 1080–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.119

Grossman, M. R., & Gruenewald, T. L. (2020). Failure to meet generative self-expectations is linked to poorer cognitive–affective well-being. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(4), 792–801. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby069

Henry, R. S., Perrin, P. B., Coston, B. M., & Calton, J. M. (2021). Intimate partner violence and mental health among transgender/gender nonconforming adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7–8), 3374–3399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518775148

ILGA Europe. (2021). Rainbow Europe-country ranking section. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.rainbow-europe.org/country-ranking

Jones-Wild, R. (2012). Reimagining families of choice. In S. Hines &Y. Taylor (Eds.), Sexualities: Past reflections, future directions. Genders and sexualities in the social sciences. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137002785_9

Karakan, E. (2014). Timing of parenthood and generativity development: An examination of age and gender effects in Turkish sample. Journal of Adult Development, 21, 207–2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-014-9192-z

López-Sáez, M. A., García-Dauder, D., Montero, I., & Lecuona, O. (2022). Adaptation and validation of the evasive attitudes of sexual orientation scale into Spanish. Journal of Homosexuality, 69(5), 925–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.1898803

McAdams, D. P., & de St. Aubin, E. (1992). A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(6), 1003–1015. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.62.6.1003

McAdams, D. P., & de St. Aubin, E., & Logan, R. L. (1993). Generativity among young, midlife, and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 8(2), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.8.2.221

Miller-McLemore, B. J. (2004). Generativity and gender: The politics of care. In E. de St. Aubin, D. P. McAdams, & T. C. Kim (Eds.), The generative society: Caring for future generations (pp. 175–194). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10622-011

Mohr, J. J., & Fassinger, R. E. (2006). Sexual orientation identity and romantic relationship quality in same-sex couples. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(8), 1085–1099. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206288281

Morris, J. F., Waldo, C. R., & Rothblum, E. D. (2001). A model of predictors and outcomes of outness among lesbian and bisexual women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.61

O’Neil-Pirozzi, T. M., Pinto, S. M., Sevigny, M., Hammond, F. M., Juengst, S. B., & Bombardier, C. H. (2022). Factors associated with high and low life satisfaction 10 years after traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 103(11), 2164–2173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2022.01.159

Oliveira, C., Mendes, A., Sequeiros, J. & Sousa, L. (2022). From older to younger generations: Intergenerational transmission of health-related roles in families with Huntington's disease. Journal of Aging Studies, 61, 101027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2022.101027

Pinazo-Hernandis, S., Zacares, J. J., Serrat, R., & Villar, F. (2022). The role of generativity in later life in the case of productive activities: Does the type of active aging activity matter? Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/01640275221122914

Pons, D., Atienza, F. L., Balaguer, I., & García-Merita, M. L. (2000). Satisfaction with Life Scale: Analysis of factorial invariance for adolescents and elderly persons. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 91(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.2000.91.1.62

Ribeiro-Gonçalves, J. A., Pereira, H., Costa, P. A., Leal, I., & de Vries, B. (2022). Loneliness, social support, and adjustment to aging in older Portuguese gay men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19(1), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00535-4

Rosati, F., Pistella, J., Nappa, M. R., & Baiocco, R. (2020). The coming-out process in family, social, and religious contexts among young, middle, and older Italian LGBQ+ adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 617217. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.617217

Roseborough, D. (2004). Conceptions of gay male life-span development. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 8(2–3), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1300/J137v08n02_03

Serrat, R., Villar, F., Pratt, M. W., & Stukas, A. A. (2018). On the quality of adjustment to retirement: The longitudinal role of personality traits and generativity. Journal of Personality, 86(3), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12326

Snapp, S., Watson, R. J., Russell, S. T., Díaz, R. M., & Ryan, C. (2015). Social support networks for LGBT young adults: Low cost strategies for positive adjustment. Family Relations, 64, 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12124

Sunderman, H., Hastings, L. & Sellon, A. (2022). “Mindset of generativity”: An exploration of generativity among college students who mentor. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2022.2090844

Szymanski, D. M., Goates, J. D., & Strauss Swanson, C. (2021). LGBQ activism and positive psychological functioning: The roles of meaning, community connection, and coping. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000499

Villar, F., López, O., & Celdrán, M. (2013). La generatividad en la vejez y su relación con el bienestar: ¿Quien más contribuye es quien más se beneficia? [Generativity in old age and its relationship with well-being: Who contributes the most, who benefits the most?]. Anales de Psicología, 29(3). https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.145171

Villar, F., Serrat, R., & Pratt, M. (2021). Older age as a time to contribute: A scoping review of generativity in later life. Ageing and Society, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21001379

von Humboldt, S., Carneiro, F., & Leal, I. (2020). Older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: What predicts adjustment to aging? Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 18(4), 1042–1048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00507-0

Werner-Lin, A. (2008). Beating the biological clock: The compressed family life cycle of young women with BRCA gene alterations. Social Work in Health Care, 47(4), 416–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981380802173509

World Health Organization [WHO]. (2020). Decade of healthy ageing 2020–2030. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.who.int/ageing/decade-of-healthy-ageing

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This work was supported by the National Funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/ 4255/2020 and UIDP/4255/2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Joao Tavares, Tatiana Casado, Sara Guerra, and Liliana Sousa. Analysis was performed by Joao Tavares, Tatiana Casado, and Pedro Sá-Couto. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sara Guerra, Liliana Sousa, and Joao Tavares, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Balearic Islands (UIB), Spain (162CER20).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained by all participants in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tavares, J., Casado, T., Sá-Couto, P. et al. Spanish Older LGBT+ Adults: Satisfaction with Life and Generativity. Sex Res Soc Policy (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00871-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00871-7