Abstract

Introduction

A relationship between homophobic verbal and bullying victimization has been established in the scientific literature, yet its findings remain debated. Similarly, the emotional impact of these phenomena may cross over, although not enough evidence is available to confirm this hypothesis. The study sought to examine this overlap of phenomena as well as their emotional impact, both independently and jointly, in a community-based school sample of adolescents with varying sexual orientations.

Methods

A total of 2089 Spanish students aged 11 to 18 years (M = 13.68, SD = 1.31) completed self-report measures assessing homophobic verbal and bullying victimization, sexual orientation, and emotional impact during 2017.

Results

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adolescents reported greater homophobic verbal and bullying victimization than their non-LGB peers. No differences were found in emotional impact based on sexual orientation or gender. However, differences were found for victimization type, with LGB youth overrepresented in the poly-victim group. A mediation effect of homophobic verbal victimization was observed between bullying victimization and negative emotional impact.

Conclusions

LGB students more frequently experience more types of victimization than their non-LGB peers. Homophobic victimization amplifies the likely emotional impact of bullying victimization, which should be considered in prevention programs and psychological interventions.

Policy Implications

These findings highlight the importance of sexual diversity in the study of bullying behavior. It is also identified as a key area when developing prevention programs aimed at eradicating this type of violence from our schools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over the last two decades, the scientific literature on the prevalence of and outcomes associated with homophobic bullying among adolescents has increased steadily (Espelage et al., 2019). This kind of bullying has been defined as a type of stigma-based bullying (Earnshaw et al., 2018), directed toward students who display behaviors that fall outside the heteronormative framework. Toomey et al. (2012) define heteronormativity as “a societal hierarchical system that privileges and sanctions individuals based on presumed binaries of gender and sexuality” (p. 188). Homophobic bullying and/or the use of homophobic slurs (e.g., that is so gay, no homo) can be directed toward not only lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals, but also non-LGB students who are gender non-conforming and who do not uphold the behaviors expected of male and female gender roles (Meyer, 2008; Poteat & Espelage, 2005). Moreover, Birkett et al. (2009) found that adolescents who question their sexual orientation are also frequent targets of homophobic bullying.

Regarding prevalence, numerous studies have shown homophobic bullying to be more prevalent than bullying, recording rates between 30 and 75–80% of victims in most studies carried out over the last decade in Europe and the USA (e.g., European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2013; Hinduja & Patchin, 2020; Kosciw et al., 2018). Studies in Spain report the same trend, namely a higher prevalence rate of bullying and cyberbullying in sexual minorities (Benítez, 2016a; Llorent et al., 2016; Pichardo & de Stéfano, 2015), with some studies identifying almost twice as many non-heterosexual student victims in bullying and cyberbullying than heterosexual student victims (Elipe et al., 2018; Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020). In general, research indicates that LGBTQ + Footnote 1youth report being the target of homophobic bullying more so than straight-identified youth (for meta-analyses, see Fedewa & Ahn, 2011; Toomey & Russell, 2016). However, the way in which each study has operationalized homophobic bullying varies, making it difficult to establish clear conclusions. Specifically, some studies collect data on bullying (or cyberbullying) and identify differences in prevalence according to gender or sexual orientation, assuming that victimization (e.g., physical, verbal, social exclusion) in sexual minorities would be homophobic bullying because of their targets (e.g., Elipe et al., 2018; Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020; Hinduja & Patchin, 2020; Llorent et al., 2016). Other studies directly ask whether victimization (or cybervictimization) is motivated by sexual orientation or gender (e.g., Benitez, 2016a; Kosciw et al., 2018; Poteat et al., 2013). A limited number also include specific types of homophobic victimization, that is, homophobic-specific aggressive behaviors, mainly verbal homophobic victimization (Poteat & Espelage, 2007; Pichardo & de Stéfano, 2015), whereas some studies use community-based school samples (e.g., Elipe et al., 2018; Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020; Hinduja & Patchin, 2020; Llorent et al., 2016); others use samples encompassing minority sexual youth only (e.g., European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2013; Kosciw et al., 2018).

Homophobic Verbal and Bullying Victimization

In terms of homophobic behaviors, most studies have identified verbal homophobic aggressions as the most prevalent homophobic victimization type. Specifically, Birkett et al. (2009) found that 91.4% of LGB middle-school and high-school students sometimes or frequently heard homophobic remarks in school such as “faggot,” “dyke,” and “queer.” Similar data were reported in the USA in GLSEN’s National School Climate Survey; 98.5% of LGBTQ students reported having heard “gay” used in a pejorative way, and 70.1% of students were verbally harassed given their sexual orientation, and 59.1% based on gender in the past year (Kosciw et al., 2018). In Spain, between 60 and 80% of students reported having witnessed homophobic verbal aggressions (Gómez et al., 2012; INJUVE, 2011; Pichardo & de Stéfano, 2015), and around 70% of LGB students reported having been insulted via homophobic remarks and confirmed having been victims of rumors (Benítez, 2016b). However, the relationship between homophobic verbal and bullying victimization still needs to be clarified. From this perspective, bullying and its overlap with homophobic language has been previously established (Birkett & Espelage, 2015; Espelage et al., 2015; Espelage et al., 2018; Merrin et al., 2018; Poteat et al., 2012; Poteat & Rivers, 2010). Yet this raises two questions: First, is homophobic verbal victimization part of the bullying victimization pattern, and, if so, does this pattern correspond to specific students, namely sexual minorities? And second, should homophobic verbal victimization be considered a completely independent behavior, unrelated to bullying victimization?

Emotional Impact and Consequences of Homophobic Verbal and Bullying Victimization

The short-term emotional impact on victims can prove decisive in the development of relational dynamics underlying bullying processes (Donoghue et al., 2014). Previous studies on bullying and cyberbullying have revealed significant differences in emotional impact according to personal factors such as gender and age, but most particularly in relation to the type of bullying experienced, severity of episodes, roles played, and poly-victimization (Giménez et al., 2015; Gradinger et al., 2009; Ortega et al., 2009; Ortega et al., 2012). However, studies that specifically focus on emotional impact in homophobic victimization, especially over and above bullying victimization, are scarce, and some generate controversy in some areas. While the majority of studies have found significant correlations between homophobic name-calling and several educational, psychosocial, and mental health concerns (e.g., Poteat & Espelage, 2007; Rinehart et al., 2020; Tucker et al., 2016), other studies have documented different results. For example, Collier et al. (2013a) found that homophobic name-calling was not independently associated with psychological distress after controlling for gender, sexual attraction, gender non-conformity, and other negative treatment by peers; Poteat et al. (2013) did not find effect of this victimization type, over and above bullying victimization, on depression but did observe an effect on anxiety. Furthermore, some studies have reported a different impact of homophobic verbal victimization according to gender as well as sexual orientation (Birkett et al., 2009; Poteat & Espelage, 2007; Poteat et al., 2011).

On the other hand, poly-victimization—the experience of multiple kinds of victimization—has shown to have a significant effect on emotional impact; it is also related to trauma symptoms (Felix et al., 2009; Mitchell et al., 2020). However, the majority of poly-victimization studies either include other victimization types unrelated to bullying (e.g., Johns et al., 2021; Sterzing et al., 2019) or refer to general bullying (Espelage et al., 2016); they fail to cover homophobic and bullying victimization together.

Current Study

Homophobic verbal and bullying victimization are clearly established phenomena in the literature. However, empirical results to date concerning their relationship and impact on victims are inconclusive and raise certain important questions: (a) Do both phenomena fall under a broader phenomenon, namely homophobic bullying? (b) Do both phenomena affect victims differently according to variables such as gender and sexual orientation? And (c) is the emotional impact of both phenomena likely to overlap?

This study aims to add empirical evidence to support and clarify the questions posed. Specifically, the study analyzes the immediate emotional impact of homophobic verbal and bullying victimization, as well as the impact of both phenomena taken together. To our knowledge, there are no published studies which focus on examining the immediate emotional impact behind these two types of victimization and how they relate. Furthermore, we are unaware of any Spanish research that reports prevalence data on both victimization types.

We hypothesize that homophobic verbal victimization may have a different effect on victims compared with bullying victimization because of its unique characteristics, in that it imposes a certain stigma on victims; because of the victims’ sexual orientation (impacting more on LGB youth owing to other stressors experienced by these students); and because of its frequent overlap with bullying victimization, thus exacerbating the impact involved.

The study objectives were as follows:

-

(a)

To assess the prevalence of homophobic verbal victimization and bullying victimization, as well as the overlap between both victimization types—in other words, poly-victimization, considering gender and sexual orientation

-

(b)

To assess the emotional impact of victimization by victimization type (bullying victimization, homophobic verbal victimization, or poly-victimization), gender, and sexual orientation

-

(c)

To test possible mediator effects of homophobic verbal victimization on the relationship between bullying victimization and emotional impact

Method

Participants

The sample comprised 2089 adolescents (47% girls; 53% boys) from nine schools in two southern Spanish cities (Cordova and Seville). Six were state schools, and three were state-funded schools. Four were urban schools, and five belonged to rural areas. Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants. The range of schools selected guaranteed that students with different socioeconomic statuses and backgrounds were included.

Students ranged from 11 to 18 years (M = 13.68, SD = 1.31); they were in their first through fourth years of compulsory secondary education (ESO) and their first year of vocational education (FP). Regarding sexual orientation, 85.4% of the sample was heterosexual, 1.4% lesbian or gay, 6% bisexual, and 7.2% non-attracted to boys or girls.

Measures

Participants completed self-report questionnaires that assessed bullying victimization, homophobic verbal victimization, and emotional impact associated with victimization. The demographic variables considered in this study were age, gender, and sexual orientation.

Bullying Victimization

The Victimization sub-scale from the Spanish version of the European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (EBIPQ; Ortega-Ruiz et al., 2016) was used to assess experiences as a victim of bullying in the last two months. This scale comprises seven items and assesses verbal and physical forms of bullying (e.g., someone has hit me, someone has insulted me). Response options are 0 = never; 1 = once or twice; 2 = once or twice a month; 3 = around once a week; and 4 = more than once a week. This scale has shown adequate psychometric properties in previous studies. Internal consistency of the Victimization sub-scale in this study was α = .77.

Homophobic Verbal Victimization

Four items—two corresponding to face-to-face interaction and two specific to the online context—were used to assess this victimization type. Items referred to having been insulted using homophobic epithets (e.g., fag, butch) and having been teased about one’s gender expression (appearance, clothes, and behavior). Participants were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never to 4 = more than once a week. The internal consistency was α = .66.

Victimization Emotional Impact

The Cyberbullying Victimization Emotional Impact Scale (CVEIS; Elipe et al., 2017) was used to assess the emotional impact of experiencing victimization. The scale comprises 18 items distributed across three factors: (a) active impact, six items (e.g., energetic, lively; determined, daring; active, alert), α = .91; (b) depressed impact, nine items (e.g., scared, afraid; defenseless, helpless; depressed, sad), α = .93; and (c) annoyed impact, three items (annoyed, angry; irritable, in a bad mood; choleric, enraged), α = .89. This scale presents advantages over other measures when it comes to assessing emotional impact; not only does it cover the obvious negative emotions (those included under the depressed factor), but it also encompasses other less obvious emotions present among part of the population according to studies, such as anger-driven emotions (annoyed factor) and activation emotions (active factor). The scale has shown adequate psychometric properties in previous studies (Del Rey et al., 2019). Participants were asked how much they experienced each emotion when victimized on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = a lot.

Sexual Orientation

Two items were used to assess sexual orientation: “Regarding erotic–affective relationships, I feel attracted to girls” and “Regarding erotic–affective relationships, I feel attracted to boys.” Response options ranged from 0 = I do not agree to 4 = I completely agree on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The answers were combined with self-reported gender (boy vs. girl), and the following categories were created: (1) heterosexual, agree to feeling attracted to the opposite gender only; (2) lesbian/gay, agree to feeling attracted to the same gender only; (3) bisexual, agree to feeling attracted to the same and opposite sex; and (4) non-attracted to boys or girls.

Procedure

First, consent from the Andalusia Biomedical Research Ethics Coordinating Committee was obtained (0568-N-14); following this, several schools were sent an email inviting them to collaborate. Invitations were addressed to the school board for review and approval by the school council. The school council consisted of members from across the whole school community: school board, teachers, parents and legal guardians, administrative staff, and students. The invitation outlined the research purpose and aims, as well as what was expected and required of participants. Once consent and approval were obtained, questionnaire administration dates were agreed with the teaching staff. The questionnaires were administered by teachers using the paper-and-pencil format during class hours. Throughout survey administration, students were reminded that their participation was voluntary and confidential and that they could skip any questions or discontinue at any time without penalty. Survey administration lasted approximately 40 min. Data were collected during academic year 2017.

Data Analyses

First, a categorical variable labeled “victimization type” was created using the homophobic verbal and bullying victimization variables. The established categories were (a) non-victims, namely students who reported no victimization experiences or reported experiencing victimization only once or twice; (b) bullying victims, namely students who reported experiencing at least one of the seven aggressive bullying behaviors once or twice a month or more frequently, plus none of the homophobic aggressive behaviors; (c) homophobic verbal victims, namely students who reported having experienced at least one of the homophobic aggressive behaviors once or twice a month or more frequently, plus none of the aggressive bullying behaviors; and (d) poly-victims, namely students who reported having experienced both homophobic verbal and bullying victimization once or twice a month, or more frequently. The prevalence of each victimization type, as well as their correlation with age, gender, and sexual orientation, was analyzed using a contingency table. To test for association significance, chi-square statistics and corrected standardized residuals (CSRs) were run. CSR values equal to or higher than ± 1.96 and ± 2.58 mean that the percentage is higher or smaller than that expected by chance, with a confidence level of 95% and 99%, respectively. Next, differences for each emotional impact type by victimization, sexual orientation, and gender, and controlling age effect, were tested using analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Lastly, several mediation models were tested. Accordingly, bivariate correlations assessing all between-variable associations included in the models (homophobic verbal victimization, bullying victimization, and emotional impact) were obtained; independent analyses were then computed to determine whether homophobic verbal victimization mediated the relationship between bullying victimization and emotional impact. We tested whether the direct effect coefficient of bullying victimization on emotional impact decreased (partial) or became non-significant (total) when homophobic verbal victimization was introduced as a mediator in the model. The strength and significance of the models were tested using the bootstrap method with 10,000 iterations and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (Preacher et al., 2007). CIs were considered statistically significant if the lower-to-upper bound did not cross zero.

All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 24. Mediation analyses were computed using the PROCESS macro (v. 3.4.) in SPSS (Hayes, 2018).

Results

Prevalence of Homophobic Verbal and Bullying Victimization

Approximately 30% of students identified themselves as victims. The most prevalent victimization type was bullying victimization (21.2%), followed by poly-victimization (6.9%). Only 1.2% of participants reported having only experienced homophobic verbal victimization.

There was no significant correlation between victimization type and gender (χ2 [3, 2083] = 6.59, p = .086), nor between victimization type and age (χ2 [21, 2073] = 18.15, p = .640).

Regarding sexual orientation, the categories lesbian/gay and bisexual were combined owing to the low prevalence of gay and lesbian students. Thus, we used the following variable categories in our sexual orientation analyses: heterosexual (1642, 85.4%); lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) (142, 7.4%); and non-attracted to boys and girls (n = 139, 7.2% of valid data).

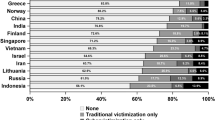

The association between victimization type and sexual orientation was significant (χ2 [6, 1923] = 48.420, p < .001). Specifically, and as shown in Table 1, a significantly higher proportion of LGB students than expected by chance reported experiencing bullying victimization and poly-victimization, and a significantly higher proportion of heterosexual students categorized themselves as non-victims. Homophobic verbal victimization was not significantly associated with sexual orientation, with 22 out of the 24 homophobic victims being heterosexual individuals.

Victimization Emotional Impact

Analyses of the emotional impact of victimization were conducted on those students who identified themselves as victims (n = 621). In Table 2, means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis for each of the three emotional impact types are shown.

The emotional impact of each bullying type was generally low, ranging from 0 to 4. The annoyed impact yielded the highest mean and the active impact the lowest.

Differences in emotional impact as a function of victimization type, sexual orientation, and gender were tested in each emotional impact type. None of the variables showed a significant effect for active impact (FVictim type [2, 496] < 1; FSexual orientation [2, 496] = 1.908; FGender [1, 496] < 1). No interactions were significant: victimization × sexual orientation (F [3, 496] = 1.224); victimization × gender (F [2, 496] = 2.810); sexual orientation × gender (F [2, 496] < 1); victimization × sexual orientation × gender (F [2, 496] < 1).

Regarding the depressed impact, significant differences were found for the main effect of victimization type (F [2, 498] = 6.587, MSe = 7.373, η2p = .027 p < .01); according to the post-hoc tests, the differences were between poly-victimization (M = 1.31, SD = 1.18) and the remaining groups, bullying victimization (M = 0.85, SD = 1.04), and homophobic verbal victimization (M = 0.41, SD = 0.75). There were no significant effects for sexual orientation (F [2, 498] < 1) or gender (F [1, 498] = 2.301). No significant interactions were recorded: victimization × sexual orientation (F [3, 498] < 1); victimization × gender (F [2, 498] = 1.014); sexual orientation × gender (F [2, 498] = 1.601); victimization × sexual orientation × gender (F [2, 498] < 1).

The results for the annoyed impact were similar to those recorded for depressed: a significant main effect of victimization type (F [2, 497] = 4.516, MSe = 7.386, η2p = .018, p < .05), yielding differences between poly-victimization (M = 1.54, SD = 1.36) and homophobic verbal victimization (M = 0.64, SD = 1.07). There were no significant effects for sexual orientation (F [2, 497] = 1.101) or gender (F [1, 497] < 1). No interactions were significant: victimization × sexual orientation (F [3, 497] < 1); victimization × gender (F [2, 497] < 1); sexual orientation × gender (F [2, 496] < 1); victimization × sexual orientation × gender (F [2, 497] = 1.636).

Mediation Models

Because the mediation models were designed to test for emotional impact, they were only conducted on students who identified themselves as victims.

We tested whether homophobic verbal victimization mediated the relationship between bullying victimization and depressed and annoyed emotional impact. We did not test the model for active emotional impact given the absence of significant differences in this impact type based on the victim type found in the previous ANOVAs. Similarly, we did not run mediation analysis by gender or sexual orientation.

Bivariate correlations between the variables used in the mediation analyses are shown in Table 3. As can be seen, all correlations were significant and ranged from moderate to high.

The results across all analyses reveal that the confidence interval of the total effect (direct and indirect combined) of bullying victimization on emotional impact was significant (see Table 4), which confirms the partial mediation effects. The models explained 16% of the variance in the case of depressed impact and half of this (8%) in the case of annoyed impact. As shown in the coefficients presented in Fig. 1 and Table 4, homophobic verbal victimization partially mediated the effect of bullying victimization on depressed impact and annoyed impact.

Discussion

The current study provides data on homophobic and bullying victimization according to sexual orientation. In addition, this research addresses a gap in the scientific literature by examining the immediate emotional impact of different victimization types on students, confirming the partial mediation effect of homophobic verbal victimization between bullying victimization and negative emotional impact: depressed and annoyed.

The results presented herein contribute to a growing body of research and have shown that bullying victimization as well as homophobic victimization is more prevalent among LGB students than their non-LGB peers (e.g.,Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020; Hinduja & Patchin, 2020; Kosciw et al., 2018). Indeed, the findings reported here support the notion that bullying victimization and homophobic verbal victimization are significantly more prevalent in LGB youth, with half of the LGB youth in our study victims of some form of victimization compared with around a quarter in the case of heterosexual and non-attracted to boys or girls students, results similar to those previously found by Elipe et al. (2018). The differences in prevalence between LGB and heterosexual youth were especially prominent among poly-victims. Rates were three times higher among LGB students compared to the other two student groups for experiencing bullying victimization plus homophobic verbal victimization. This finding coincides with previous studies conducted in Spain and other countries, which have reported a higher “amount” of victimization among sexual minority youth (Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020; Mitchell et al., 2020). This leads us to believe that aspects of homophobic bullying may be characterized as amplified patterns of bullying, as also suggested in previous research (e.g., Espelage & Swearer, 2008; Espelage et al., 2018), in which bullying and homophobic aggressive behaviors are mainly targeted toward LGB students, but also toward other non-heteronormative students (LGBTQ +) not assessed in this study. However, we did not observe gender-related differences in victimization prevalence, contrary to previous studies (Collier et al., 2013a, b; Hinduja & Patchin, 2020). In addition, the proportion of victims among students who reported not feeling attracted to either boys or girls was similar to that observed among their heterosexual peers. This finding, coupled with the fact that LGB youth reported the highest rates of both bullying victimization and homophobic verbal victimization, suggests that the issue is not related to majority versus minority sexual orientation, quantitatively speaking, but to homophobic attitudes.

As for the emotional impact of victimization, scores were higher in the depressed and annoyed impact for poly-victims. Victimization type alone, mainly poly-victimization, was associated with emotional impact. Therefore, it seems that experiencing multiple forms of victimization is related to emotional impact, regardless of gender or sexual orientation. These results contradict earlier research, which identified different consequences of homophobic bullying by sexual orientation (Almeida et al., 2009; Birkett et al., 2009; Poteat et al., 2011). Our results coincide more with studies which observed victimization effects independently of gender or sexual orientation (Collier et al., 2013a, b; Wang et al., 2018). However, to our knowledge, no studies to date have performed comparative analyses on the immediate emotional impact of bullying victimization and homophobic verbal victimization by sexual orientation and gender, the main contribution of this work. Our results suggest that the “amount” of victimization outperforms other personal variables when it comes to emotional impact. On the other hand, the emotional impact scores were lower for homophobic verbal victimization compared to other victim types. This, coupled with the fact that only about 1% of students across the total sample reported having only experienced homophobic verbal victimization, and that the vast majority were heterosexual students, suggests that isolated cases of homophobic aggression aimed at heterosexual peers may not be part of a bullying pattern, but rather a way of affirming heteronormativity in the group through displays of homophobic behavior. Several empirical studies support this idea, in which homophobic attitudes and behaviors are found to be similar among members of adolescent friendship groups, and will become even more similar when observed over time (Birkett & Espelage, 2015; Espelage et al., 2019; Poteat, 2007, 2008). From this perspective, Kowalski (2004) suggests that the level of identity threat posed by homophobic verbal victimization might vary according to the target’s actual sexual orientation and gender expression. Thus, this might explain the results found for homophobic verbal victimization exclusively in the heterosexual group, unrelated to a bullying pattern and with low emotional impact. So, answering the first question formulated in the introduction section, homophobic verbal victimization is part sometimes of a bullying pattern, specially addressed to LGB or gender non-conforming students. But, in other occasions, it could be better understood as a behavior that contributes to create a hostile environment to sexual diversity. Therefore, in these latter cases, it will be a risk factor to homophobic bullying, but not homophobic bullying in itself. As Collier et al. (2013b) claim, it would be important to develop measures sensitive enough to assess victimization type and specific enough to differentiate between casual (however unacceptable) uses of sexually prejudiced language that are not meant to intimidate. Additionally, the consequence of the use of sexually prejudiced language, even without intention to intimidate, will mean a bullying climate to some students, especially those who feel their identity, orientation, or gender expression threatened by this kind of language.

On the other hand, considering that LGB students are often victimized in multiple ways, and given the stronger impact of this poly-victimization, this would appear to reinforce previous conclusions about the significant negative effects of homophobic bullying on health (Abreu & Kenny, 2018; Moyano & Sánchez-Fuentes, 2020). Furthermore, the fact that victimization type alone, with no implication from gender and sexual orientation, was significantly associated with adverse emotional impact, suggests that victimization has a direct effect on emotional impact and perhaps links to health outcomes, consistent with previous studies (Birkett et al., 2015; Meyer, 2003). Therefore, homophobia and the use of homophobic language, not sexual orientation or identity, should be a priority area in school-based violence prevention programs.

Finally, the results partially confirm the posed hypothesis: homophobic verbal victimization has a specific impact on victims but only when associated with bullying victimization. Moreover, the partial mediation effect of homophobic verbal victimization observed between bullying victimization and negative emotional impact coincides with other studies that report significant effects of sexual orientation–based victimization on mental health (Birkett et al., 2009, 2015; Burton et al., 2014; Garaigordobil & Larrain, 2020). Thus, adopting Meyer’s (2003) minority stress framework, it is clear that LGB youth experience higher levels of victimization than their heterosexual and non-attracted to boys or girls peers, and are frequently exposed to additional stressors such as homophobic remarks or mockery about how they dress and behave. As a result, they are likely susceptible to increased negative emotional impact.

These results offer valuable insight at a social policy level. Although advances in legislation clearly highlight a commitment to the social rights of sexual minorities and therefore society as a whole, the fact that LGB students experience increased victimization, and in several ways poly-victimization, throughout their daily lives tells us that much more needs to be done to achieve true sexual diversity equality. Previous studies have also shown that general anti-bullying programs are ineffective at tackling this type of victimization (Earnshaw et al., 2018). This implies that the most vulnerable students are those who least benefit from general school policies. It is therefore imperative to design specific measures that protect all youth and not just those who belong to the so-called mainstream group.

This study has several strengths. Our assessment included youth not sexually interested in boys or girls, which is often overlooked in research. This inclusion allowed us to compare victimization experiences among these youth relative to their LGB peers. Consequently, some interesting conclusions were drawn. Another strength was the use of a school-based sample. Many studies into homophobic bullying have used community-based convenience samples of LGBT youth (e.g., European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2013; Kosciw et al., 2018). Sampling from LGBT associations and groups may limit the generalizability of the study’s findings because youth belonging to these settings are inherently different from the general LGB population (e.g., less likely to “out”). Although we drew our sample from schools, we did not sample enough students to examine the wider spectrum of sexual diversity (e.g., transgender and gender non-conforming students). Moreover, to our knowledge, this is the only Spanish study to date which assesses not only the prevalence of bullying victimization and homophobic verbal victimization, but also the emotional impact of these phenomena.

The study also has several limitations. First, our merging of the lesbian/gay and bisexual categories, together with our decision not to directly assess the category “I am not sure,” sometimes referred to as “questioning,” rendered our sexual minority data less precise. Second, the number of students reported having experienced only homophobic verbal victimization was very low, which may have affected the statistical power of some statistical analyses. Third, we only assessed verbal victimization, the most common form, thus excluding physical and social homophobic victimization from our research. In future studies, wider measures encompassing other types of homophobic victimization should be included. Fourth, as the data were cross-sectional, this did not allow for the temporal timing of victimization and emotional impact. Longitudinal studies would prove highly beneficial for researching these phenomena.

Conclusions

LGB students were most affected by bullying victimization and homophobic verbal victimization, notably overrepresented as poly-victims. In terms of prevalence, half of all LGB students experienced some kind of victimization. Regarding emotional impact, bullying victimization joined by homophobic verbal victimization made the emotional impact stronger, with students affected by both categories scoring higher on emotions related to depressed and annoyed states. Thus, homophobic bullying seems to be a complex pattern of aggression mainly, but not exclusively, targeted toward LGB students, which sometimes combines with bullying and homophobic victimization. When both victimization types occur at the same time, the emotional impact is stronger than that of bullying only. Homophobic bullying represents a significant public health concern that seems to affect LGB youth more so than other youth, and appears to be significantly associated with negative emotional impact in general. This study contributes to the existing literature and reaffirms the importance of addressing homophobic language in school settings to understand its complexities and to minimize the long-term impact of this type of gendered aggression for all youth. Despite the growing scientific literature on this topic in recent years, a clearly defined and operational definition for homophobic bullying, which enables a common assessment by the scientific community, is still lacking. Future research endeavors should focus on bringing about a scientific consensus that welcomes collective advances in this field of study.

Availability of Data and Material

Del Rey, R.& Elipe, P. (2021). Exploratory survey (2017) on homophobic verbal and bullying victimization: dataset. Data available upon request. Please email the first author for access.

Change history

10 October 2021

The original version of this paper was updated. The funding note "Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature" was inserted.

Notes

This article employs the term “LGBTQ + ” to refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, and/or gender non-conforming individuals/groups.

References

Abreu, R. L., & Kenny, M. C. (2018). Cyberbullying and LGBTQ youth: A systematic literature review and recommendations for prevention and intervention. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 11(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0175-7

Almeida, J., Johnson, R. M., Corliss, H. L., Molnar, B. E., & Azrael, D. (2009). Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 1001–1014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9

Benítez, E. (Coord). (2016a). Ciberbullying LGBT-fóbico. Nuevas formas de intolerancia. [Cyberbullying LGBT-phobic. New ways of intolerance].Madrid: Grupo de Educación de COGAM. https://cogameduca.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/4-ciberbullying-lgbt-fc3b3bico-informe-completo-web.pdf

Benítez, E. (Coord.) (2016b). LGBT-fobia en las aulas 2015. ¿Educamos en la diversidad afectivo-sexual? [Do we educate on affective and sexual diversity?].Madrid: Grupo de Educación de COGAM. https://cogameduca.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/1-lgbt-fobia-en-las-aulas-2015-informe-completo-web.pdf

Birkett, M., & Espelage, D. L. (2015). Homophobic name-calling, peer-groups, and masculinity: The socialization of homophobic behavior in adolescents. Social Development, 24(1), 184–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12085

Birkett, M., Espelage, D. L., & Koenig, B. (2009). LGB and questioning students in schools: The moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 989–1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9389-1

Birkett, M., Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2015). Does it get better? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress and victimization in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(3), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.275

Burton, C. M., Marshal, M. P., & Chisolm, D. J. (2014). School absenteeism and mental health among sexual minority youth and heterosexual youth. Journal of School Psychology, 52(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.12.001

Collier, K. L., Bos, H. M. W., & Sandfort, T. G. M. (2013a). Homophobic name-calling among secondary school students and its implications for mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(3), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9823-2

Collier, K. L., Van Beusekom, G., Bos, H. M. W., & Sandfort, T. G. M. (2013b). Sexual orientation and gender identity/expression related peer victimization in adolescence: A systematic review of associated psychosocial and health outcomes. Journal of Sex Research, 50(4), 299–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.750639

Del Rey, R., Ojeda, M., Casas, J. A., Mora-Merchán, J. A., & Elipe, P. (2019). Sexting among adolescents: The emotional impact and influence of the need for popularity. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01828

Donoghue, C., Almeida, A., Brandwein, D., Rocha, G., & Callahan, I. (2014). Coping with verbal and social bullying in middle school. The International Journal of Emotional Education, 6(2), 40–53. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar//handle/123456789/6224

Earnshaw, V. A., Reisner, S. L., Menino, D. D., Poteat, V. P., Bogart, L. M., Barnes, T. N., & Schuster, M. A. (2018). Stigma-based bullying interventions: A systematic review. Developmental Review, 48(January), 178–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.001

Elipe, P., Muñoz, M. O., & Del Rey, R. (2018). Homophobic bullying and cyberbullying: Study of a silenced problem. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(5), 672–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1333809

Elipe, P., Mora-Merchán, J. A., & Nacimiento, L. (2017). Development and validation of an instrument to assess the impact of cyberbullying: The Cybervictimization Emotional Impact Scale. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(8), 479–485. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0069

Espelage, D. L., Basile, K. C., De La Rue, L., & Hamburger, M. E. (2015). Longitudinal associations among bullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(14), 2541–2561. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514553113

Espelage, D. L., Hong, J. S., & Mebane, S. (2016). Recollections of childhood bullying and multiple forms of victimization: Correlates with psychological functioning among college students. Social Psycholgy of Educaction, 19, 715–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9352-z

Espelage, D. L., Hong, J. S., Merrin, G. J., Davis, J. P., Rose, C. A., & Little, T. D. (2018). A longitudinal examination of homophobic name-calling in middle school: Bullying, traditional masculinity, and sexual harassment as predictors. Psychology of Violence, 8(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000083

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2008). Addressing research gaps in the intersection between homophohia and bullying. School Psychology Review, 37(2), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2008.12087890

Espelage, D. L., Valido, A., Hatchel, T., Ingram, K. M., Huang, Y., & Torgal, C. (2019). A literature review of protective factors associated with homophobic bullying and its consequences among children & adolescents. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.003

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2013). EU LGBT survey: Results at a glance. https://doi.org/10.2811/37741

Fedewa, A. L., & Ahn, S. (2011). New developments in the field: The effects of bullying and peer victimization on sexual-minority and heterosexual youths: A quantitative meta-analysis of the literature. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 7(4), 398–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2011.592968

Felix, E. D., Furlong, M. J., & Austin, G. (2009). A cluster analytic investigation of school violence victimization among diverse students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(10), 1673–1695. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509331507

Garaigordobil, M., & Larrain, E. (2020). Bullying and cyberbullying in LGBT adolescents: Prevalence and effects on mental health. Comunicar, 28(62), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.3916/c62-2020-07

Giménez, A. M., Hunter, S. C., Durkin, K., Arnaiz, P., & Maquilón, J. J. (2015). The emotional impact of cyberbullying: Differences in perceptions and experiences as a function of role. Computers and Education, 82, 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.11.013

Gómez, A., Generelo, J., Ferrándiz, J. L., Garchitorena, M., Montero, P., & Hidalgo, P. (2012). Acoso escolar homofóbico y riesgo de suicidio en adolescentes y jóvenes LGB. [Homophobic bullying and suicide risk in adolescents and LGB youth]. Madrid: FELGTB-COGAM.

Gradinger, P., Strohmeier, D., & Spiel, C. (2009). Traditional bullying and cyberbullying: Identification of risk groups for adjustment problems. Journal of Psychology, 217(4), 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1027/0044-3409.217.4.205

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process anaylsis. A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guidlford Press.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2020). Bullying, cyberbullying, and LGBTQ students. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://cyberbullying.org/bullying-cyberbullying-sexual-orientation-lgbtq.pdf

INJUVE. (2011). Jóvenes y diversidad sexual [Young people and sexual diversity]. http://www.injuve.es/observatorio/salud-y-sexualidad/jovenes-y-diversidad-sexual

Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Hipp, T. N., Robin, L., & Shafir, S. (2021). Differences in adolescent experiences of polyvictimization and suicide risk by sexual minority status. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(1), 240–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12595

Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Zongrone, A. D., Clark, C. M., & Truong, N. L. (2018). The 2017 National School Climate Survey. (GLSEN, Ed.). New York. https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/Full_NSCS_Report_English_2017.pdf

Kowalski, R. M. (2004). Proneness to, perceptions of, and responses to teasing: The influence of both intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. European Journal of Personality, 18(4), 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.522

Llorent, V. J., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Zych, I. (2016). Bullying and cyberbullying in minorities: Are they more vulnerable than the majority group? Frontiers in Psychology, 7(October), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01507

Merrin, G. J., de la Haye, K., Espelage, D. L., Ewing, B., Tucker, J. S., Hoover, M., & Green, H. D. (2018). The co-evolution of bullying perpetration, homophobic teasing, and a school friendship network. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(3), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0783-4

Meyer, E. J. (2008). Gendered harassment in secondary schools: Understanding teachers’ (non) interventions. Gender and Education, 20(6), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802213115

Meyer, I. H. (2003, September). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. NIH Public Access. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Mitchell, K. J., Jones, L. M., Turner, H. A., Hamby, S., Farrell, A., Cuevas, C., & Daly, B. (2020). Exposure to multiple forms of bias victimization on youth and young adults: Relationships with trauma symptomatology and social support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01304-z

Moyano, N., & del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes, M. (2020). Homophobic bullying at schools: A systematic review of research, prevalence, school-related predictors and consequences. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101441

Ortega-Ruiz, R., Del Rey, R., & Casas, J. A. (2016). Evaluar el bullying y el cyberbullying validación española del EBIP-Q y del ECIP-Q. Psicologia Educativa, 22(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.01.004

Ortega, R., Elipe, P., Mora-Merchán, J. A., Calmaestra, J., & Vega, E. (2009). The emotional impact on victims of traditional bullying and cyberbullying: A study of Spanish adolescents. Journal of Psychology, 217(4). https://doi.org/10.1027/0044-3409.217.4.197

Ortega, R., Elipe, P., Mora-Merchán, J. A., Genta, M. L., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., Tippett, N. (2012). The emotional impact of bullying and cyberbullying on victims: A European cross-national study. Aggressive Behavior, 38(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21440

Pichardo, J. I., & de Stéfano, M. (Eds.) (2015). Diversidad sexual y convivencia. Una oportunidad educativa. [Sexual diversity and school coexistence. An educational opportunity].Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Poteat, V. P. (2007). Peer group socialization of homophobic attitudes and behavior during adolescence. Child Development, 78(6), 1830–1842. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01101.x

Poteat, V. P. (2008). Contextual and moderating effects of the peer group climate on use of homophobic epithets. School Psychology Review, 37(2), 188–201.

Poteat, V. P., DiGiovanni, C. D., & Scheer, J. R. (2013). Predicting homophobic behavior among heterosexual youth: Domain general and sexual orientation-specific factors at the individual and contextual level. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(3), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9813-4

Poteat, V. P., & Espelage, D. L. (2005). Exploring the relation between bullying and homophobic verbal content: The Homophobic Content Agent Target (HCAT) scale. Violence and Victims, 20(5), 513–528. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.2005.20.5.513

Poteat, V. P., & Espelage, D. L. (2007). Predicting psychosocial consequences of homophobic vcitimization in middle school students. Journal of Early Adolescence, 81(April), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.2005.20.5.513

Poteat, V. P., Mereish, E. H., Digiovanni, C. D., & Koenig, B. W. (2011). The effects of general and homophobic victimization on adolescents’ psychosocial and educational concerns: The importance of intersecting identities and parent support. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 597–609. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025095

Poteat, V. P., O’Dwyer, L. M., & Mereish, E. H. (2012). Changes in how students use and are called homophobic epithets over time: Patterns predicted by gender, bullying, and victimization status. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026437

Poteat, V. P., & Rivers, I. (2010). The use of homophobic language across bullying roles during adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31(2), 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2009.11.005

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316

Rinehart, S. J., Espelage, D. L., & Bub, K. L. (2020). Longitudinal effects of gendered harassment perpetration and victimization on mental health outcomes in adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(23–24), 5997–6016. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517723746

Sterzing, P. R., Gartner, R. E., Goldbach, J. T., McGeough, B. L., Ratliff, G. A., & Johnson, K. C. (2019). Polyvictimization prevalence rates for sexual and gender minority adolescents: Breaking down the silos of victimization research. Psychology of Violence, 9(4), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000123

Toomey, R. B., & Russell, S. T. (2016). The role of sexual orientation in school-based victimization: A meta-analysis. Youth and Society, 48(2), 176–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X13483778

Toomey, R. B., McGuire, J. K., & Russell, S. T. (2012). Heteronormativity, school climates, and perceived safety for gender nonconforming peers. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.001

Tucker, J. S., Ewing, B. A., Espelage, D. L., Green, H. D., de la Haye, K., & Pollard, M. S. (2016). Longitudinal associations of homophobic name-calling victimization with psychological distress and alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(1), 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.018

Wang, C. C., Lin, H. C., Chen, M. H., Ko, N. Y., Chang, Y. P., Lin, I. M., & Yen, C. F. (2018). Effects of traditional and cyber homophobic bullying in childhood on depression, anxiety, and physical pain in emerging adulthood and the moderating effects of social support among gay and bisexual men in Taiwan. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 1309–1317. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S164579

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all students, teachers, and school community members that collaborated in this study.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Partial financial support was received from the Andalusian Plan for Research, Development and Innovation (PAIDI, 2020), Andalucía European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) Operational Programme 2014–2020 (P18-RT-2178), and National Research Plan of the Government of Spain (PSI2017-86723-R).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Elipe: Design of the study, design of the statistical strategy to use, data analyses and interpretation, writing of the first draft of the manuscript and collaboration in the next versions, final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Espelage: Collaboration in the theoretical approach and discussion, revision and edition of the first manuscript, critical revision and edition of the several drafts until de last version. Dr. Del Rey: Design of the study, data collection, collaboration in the writing of the first draft of manuscript, collaboration in the next versions, final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research Involving Human Participants

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Andalusian Biomedical Ethical Committee (Spain) (0568-N-14).

Informed Consent

Informed consent of the parents or legal guardians was obtained through the school council. In addition, before the survey administration, students were reminded that their participation was voluntary and confidential, and the anonymous character of their answers.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elipe, P., Espelage, D.L. & Del Rey, R. Homophobic Verbal and Bullying Victimization: Overlap and Emotional Impact. Sex Res Soc Policy 19, 1178–1189 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00613-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00613-7