Abstract

HIV prevention has evolved to include the provision of HIV medications to HIV-negative persons. Known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), this intervention can reduce HIV acquisition by 96% when taken as prescribed. While previous reviews have established that PrEP is cost-effective, few have focused on the healthcare system delivery costs associated with PrEP. We undertake such a comparative analysis focusing on Ontario, Canada estimating the costs for an infectious disease physician, a primary care physician, and a nurse working in our nurse-led PrEP clinic (PrEP-RN). While the delivery of care by the nurse generated the least overall costs, we acknowledge that this would depend on how many patients breach the protocols established for nurse-led PrEP. We also highlight that targeting PrEP at persons who are at highest risk for HIV acquisition could make PrEP even more cost-effective than we estimated herein.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Giving antiretroviral medications to HIV-negative persons for prevention purposes, known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), was first determined to be efficacious in 2012 (CDC, 2018; Tan et al., 2017). In these studies, researchers evaluated the rate of HIV acquisition among persons who took emtricitabine/tenofovir DF 200/300 mg (FTC/TDF), compared with those using placebo; the outcomes were that FTC/TDF can prevent HIV acquisition by up to 96% with daily use, appropriate clinical monitoring, and condom use (CDC, 2018; Tan et al., 2017). PrEP thus revolutionized HIV prevention and has since been codified in guidelines (e.g., CDC, 2018; Tan et al., 2017).

To date, a barrier to PrEP effectiveness outside controlled trials has been access. FTC/TDF is expensive and not all prescribers feel comfortable providing it (Hannaford et al., 2018; Landers & Kapadia, 2017; Peng et al., 2018; Petroll et al., 2017). Data also suggest that many persons at risk for HIV decline PrEP because they do not feel at risk for HIV (Blumenthal et al., 2018). Other barriers include patients’ reluctance to disclose practices that put them at risk for HIV and structural inequities in the PrEP guidelines that favor certain groups over others, such as White gay men over persons of African, Caribbean, or Black descent, who have disproportionate prevalence of HIV, compared with other groups (O’Byrne, Orser, Jacob, Bourgault, & Lee, 2019).

While these individual barriers to PrEP are well noted, there remains a gap in knowledge about the healthcare system costs of PrEP delivery. Indeed, most analyses have compared the costs of FTC/TDF for PrEP against treatment costs for persons living with HIV. These studies demonstrated that PrEP is cost-effective among gay men, persons who inject drugs, and women, meaning that the costs of FTC/TDF for PrEP are lower than the costs required for a lifetime of HIV treatment (Drabo, Hay, Vardavas, Wagner, & Sood, 2016; Fu, Owens, & Brandeau, 2018; Walensky et al., 2016).

To develop a nascent understanding of such healthcare costs for PrEP, we undertook a comparative analysis, which evaluated the costs of PrEP medication and prescriber delivery in Ontario, Canada, through (1) an infectious disease (ID) specialist, (2) a primary care physician who works fee-for-service, and (3) a nurse in our nurse-led PrEP clinic (PrEP-RN). We estimated the costs for these healthcare professionals to provide PrEP to one patient and to a sample of 40 patients. We selected n = 40 because, from the published literature, this sample would fulfill the estimated number needed to treat to avert one new HIV infection. Lastly, because FTC/TDF can cause kidney damage and requires monitoring (CDC, 2018; Tan et al., 2017), we add costs for the extra follow-up that might occur based on the frequency at which such abnormal test results occurred in the published literature.

The Case Example: Background

Prior to evaluating the specific case examples, we describe the necessary healthcare follow-up for PrEP, detail the payment and billing options for each provider delivering PrEP, and calculate the cost of PrEP medication for patients. These are the parameters of our calculations.

Required Clinical Follow-Up

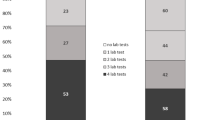

Based on current Canadian and US PrEP guidelines (CDC, 2018; Tan et al., 2017), patients attend a series of clinical visits as part of PrEP initiation and ongoing management. During these visits, patients undergo assessment for, and counseling about, PrEP and HIV prevention; physical examination and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing also occur. Provided that laboratory parameters are within normal limits (STI/HIV results and kidney function tests), there is a baseline intake visit (to assess the need for PrEP and do STI/HIV and kidney function testing), a visit 1–2 weeks later (to review results and initiate TDF/FTC), a visit after 1 month of TDF/FTC use (to review medication use and side effects and reassess HIV status and kidney function), and follow-up visits every 3 months (to repeat STI/HIV testing and kidney function assessment, to check for ongoing need for PrEP, and to provide risk reduction counseling). Based on the guidelines, assuming all results are normal, in the first year, patients would have six visits, whereas, in subsequent years, they would have four visits. Notably, some providers do a quick-start for PrEP and provide the prescription at the first visit, thus only requiring five visits in the first year (see Fig. 1). Based on a published meta-analysis (Yacoub et al., 2016), the rate of abnormal creatinine results was 3.5%, so this percentage of patients would need one additional visit per year.

Billable Services for PrEP

To situate PrEP costs, we provide details about the local healthcare system. To begin, because FTC/TDF can only be obtained through prescription, whether for HIV treatment or PrEP, and because PrEP requires HIV, creatinine, and STI testing, the number of practitioners who can provide PrEP is limited to physicians and some nurses. Within the physician group, this includes only those whose scope would include PrEP, such as ID specialists and primary care providers. For nurses, nurse practitioners can independently prescribe FTC/TDF and order the required testing for PrEP; registered nurses could also provide PrEP, including its testing, under medical directives, which can be signed by a physician or nurse practitioner in our jurisdiction.

Access to these providers, in Ontario, is limited by the single-payer remuneration system. While this system pays for patient costs for both ID specialists and primary care physicians, the former can only bill the government if certain other providers referred the patient to them (MOHLTC, 2018a). These “other providers” must have a specific government-issued billing code, and include emergency room and primary care physicians and nurse practitioners. ID specialists who manage patients without such a referral are unable to bill the single-payer provincial system. Being the first-line service providers, primary care physicians can bill the government for patients without referrals (MOHLTC, 2018a). This can take the form of a fee-for-service model, in which services are billed for as they are provided, or as a rostered patient system, in which providers receive capitation payments for their registered patients. Nurse practitioners cannot bill the government for services provided and are paid on salary or per-hour. Registered nurses are paid similarly. Access to nurse practitioners is limited to clinical settings that have sought funding from the government to employ such a provider. Oftentimes, these settings are primary care clinics that only serve registered patients of these clinics. Walk-in access for un-rostered patients, in most cases, is not permitted.

A final point about the Ontario healthcare system is that, while access to healthcare providers is insured, access to many medications is not guaranteed. Some publicly funded programs do exist, but these are restricted to, for example, persons under 25 years of age or over 65 years or age or those with low incomes (MOHLTC, 2018b). Persons aged 25–64 who do not receive social assistance must pay for medications personally, which can be out-of-pocket or through insurance programs, which can be obtained privately or through an employer. These programs then have varying degrees of drug coverage and co- or pre-payment requirements. Based on our clinical experience, FTC/TDF is covered by virtually all insurance programs.

The costs for the foregoing providers were obtained from the Ontario government’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care websites (MOHLTC, 2018a; MOHLTC, 2017). According to this fee schedule for physicians in Ontario (MOHLTC, 2018a), an ID specialist’s initial PrEP assessment costs $157.00, and each follow-up visit is $31.00. Primary care physicians, meanwhile, can bill for one STI management visit, which is $62.75 per visit (MOHLTC, 2018a). This billing code applies to “a time based all-inclusive service for the purpose of providing assessment and counselling to a patient suspected of having a STI or to a patient with a potential bloodborne pathogen.” This code should apply to the first visit for PrEP, which would include PrEP assessment (history and examination), STI/HIV testing and treatment as needed, and FTC/TDF review and prescription. For subsequent visits, primary care physicians could bill an “intermediate assessment” at $33.70, which would cover PrEP assessment and testing, or a “minor assessment” at $21.70, which would be appropriate for follow-up visits, as might be required for a review of results, abnormal laboratory result follow-up, or STI treatment (MOHLTC, 2018a). Lastly, both physician groups would generate additional billable costs for venipuncture, which could be billed by the laboratory or the physician who performs this service; for adults and adolescents, this cost is $3.54 per procedure (MOHLTC, 2017).

For our nurses, the hourly wage is $49.75 (including benefits). In our PrEP-RN clinic, the first visit is 45 min and follow-up visits are 30 min. While seemingly long for appointment times, PrEP-RN nurses do on-site specimen collection for STIs, HIV, and creatinine, meaning that patients do not take requisitions to laboratories for processing and the venipuncture cost is non-billable. These nurses also collect all histories and perform relevant physical examinations. A required component of this billing system is medical directives, which allow nurses to perform testing and treatment. In our PrEP-RN clinic, such directives have been signed by the clinic director, who is a nurse practitioner (O’Byrne, MacPherson, Orser, Jacob, & Holmes, 2019). Clinical consultations (with prescribers) are required when patient follow-up is outside the medical directive parameters, such as when they miss appointments, have abnormal laboratory results, or are symptomatic. In these cases, the nurse consults with a nurse practitioner or physician in our STI clinic.

Medication Costs

In its generic formulation, FTC/TDF costs $7.3035 per tablet (MOHLTC, 2018b), yielding an annual cost of medication of $2665.78. Added to this is a pharmacy mark-up of 8% (MOHLTC, 2014), for a total cost of $2879.05 for PrEP. Dispensing fees, additionally, average $9.93 per episode (MOHLTC, 2018b). Dispensing costs for PrEP would apply for five episodes in the first year, and four in subsequent years, adding $49.65 in the first year and $39.72 in other years.

Case Study

Building on the above costs and follow-up rates, we now explore the costs of a PrEP clinic using an ID specialist, a primary care physician, and a PrEP-RN nurse for the first and second year of PrEP delivery. We estimate these costs for a single patient and a theoretical sample of 40 patients. We chose a sample of 40 patients because, from available PrEP studies, the number needed to treat to avert one new HIV infection ranged from 18 to 38 (Buchbinder et al., 2014). A sample of 40 patients would thus help determine the costs associated with preventing one HIV infection based on a figure slightly above the highest number needed to treat to yield this outcome. We perform this analysis for the first and second years of PrEP, because, based on available PrEP guidelines (CDC, 2018; Tan et al., 2017), patients require a greater number of visits in the first year of PrEP use (six visits), compared with subsequent years (four visits). These two periods generate the high and low estimates of cost for each of these clinical service delivery approaches. Lastly, we add the follow-up required for abnormal creatinine results, based on the rate at which these occurred in the published literature, i.e., 3.5%. At this rate of 3.5%, with a sample of n = 40, one person would have an abnormal result and need an additional visit and repeat test per annum. See Tables 1 and 2 for an overview of costs.

Scenario 1: ID Specialist

For the first year, the cost of a PrEP clinic run by an ID specialist would be $364.95 per patient. This arises from one intake visit at $157.00, and five follow-up visits at $38.05, plus the $3.54 for venipuncture associated with five of these six visits (as the 2nd visit is a review of results only). For every 40 patients initiated by an ID specialist, the total costs for the first year of PrEP would be $14,598.00, plus one additional patient visit for an abnormal creatinine result, adding $38.05 in ID specialist billing costs and $3.54 for venipuncture (total = $41.59). The total cost would thus be $14,639.59 for an ID specialist to initiate 40 patients on PrEP. In subsequent years, due to the need for only four visits, these costs would reduce to $166.36 per patient (based on the $38.05 visit fee), yielding, for 40 patients, a total annual cost of $6654.40—plus one extra visit and required laboratory testing episode at $41.59, for a total of 6695.99 for an ID physician.

For the total PrEP costs (including medication), the first year would be $3293.65 ($2879.05 for FTC/TDF plus $49.65 for dispensing plus $364.95 for ID specialist services), and subsequent years would be $3085.13 ($2879.05 for FTC/TDF plus $39.72 for dispensing plus $166.36 for physician services). In this scenario, medications account for 87.4% of all costs in the first year, and 94% in all subsequent years.

Scenario 2: Primary Care Physician

Due to various billing mechanisms for primary care physicians, we estimate costs assuming that, in the first year, a family physician would bill the STI management code ($62.75) once, an intermediate assessment ($33.70) for four visits, and a minor assessment ($21.70) for the review of results visit. This approach maximizes the billable costs a primary care physician could submit. Based on these fees, for the first year, the cost per patient would be $236.95 per patient, again including the $3.54 venipuncture fee for five visits. For every 40 patients started on PrEP by primary care physicians, this would cost $9478 plus $25.24 for one abnormal creatinine result that would generate one minor assessment and venipuncture, for a total of $9503.24.

If the primary care provided opted not to use the STI management code, and instead only used the “intermediate assessment” billing option, then, in the first year, this physician would bill $33.70 for five visits and $21.70 for the second visit (review of results). This would cost, including the associated venipuncture fees, $207.90 in the first year. For our sample of 40 patients, this would yield a cost of $8316, plus one additional minor assessment ($21.70) and one venipuncture ($3.54), totaling $8341.24.

After the first year, this cost would be $148.96 per patient, based on the assumption that the family physician would use the STI management code for all visits. For every 40 patients followed by a primary care physician after the first year, the cost would be $5983.64, including $25.24 for the management of one abnormal creatinine result.

For total PrEP costs (including medication), the first year would be $3253.10 ($2879.05 for FTC/TDF plus $49.65 for dispensing plus $324.40 for physician services), and subsequent years would be $3183.93 ($2879.05 for FTC/TDF plus $39.72 for dispensing plus $265.16 for physician services). In this scenario, medications account for 88.5% of all costs in the first year and 90.4% in subsequent years.

Scenario 3: PrEP-RN

Because, in our jurisdiction, registered nurses and nurse practitioners cannot bill the fee schedule, they are paid an annual salary or hourly wage. This means cost configurations are based on time for service delivery, not fee-for-service. For intake assessments, we book 45-min appointments, which include venipuncture. The result review visit is 15 min; all other visits are 30 min. As such, our initial PrEP visit costs $37.22 (= 75% of hourly nursing wage), our results review appointment costs $12.44 (= 25% of hourly nursing wage), and all other follow-up visits cost $24.88 (= 50% of hourly nursing wage). The cost per patient for the first year of PrEP use at PrEP-RN is thus $149.28, and the costs for the first 40 patients are $5971.20 plus $12.44 for one repeat creatinine follow-up, totaling $5983.40. After the first year, these costs drop to $99.52 per patient. For 40 patients, this cost is $3980.80, plus $12.44 for one abnormal creatinine follow-up, totaling $3993.24.

For total PrEP costs (including medication), the first year would be $3077.98 ($2879.05 for FTC/TDF plus $49.65 for dispensing plus $149.28 for nursing services), and subsequent years would be $3013.89 ($2879.05 for FTC/TDF plus $35.32 for dispensing plus $99.52 for nursing services). In this scenario, medications account for 93.7% of all costs in the first year and 95.5% in subsequent years.

Summary

Our analysis highlighted that the total per-patient costs of PrEP, including medication, were similar for all service delivery approaches. At the high end, for an ID specialist, the total first-year costs were $3293.65, compared with $3077.98 for nurse delivered PrEP. The nurse thus generated only a 6.5% cost reduction. This lack of variability overall related primarily to medication costs, which accounted for a range of 87.4% to 93.5% of costs for PrEP.

When medication costs were excluded and provider costs were compared for the first year of PrEP delivery, the variation was larger. At the high end, the ID specialist costs $364.95 per patient for the first year, compared with the nurse at $149.28. The primary care physician costs $236.95 if the STI management billing code was used; this cost dropped to $207.90 if only routine intermediate assessment billing codes were used. For service delivery options, the nurse-led option was 40.9% of the cost of the ID specialist, and 63% to 72% of the cost of a primary care physician (depending on if the STI management codes were used). The primary care physician, similarly, could be 65% the cost of an ID specialist, signaling another decrease in the cost with that care delivery option if the STI management code is used. If not, the primary care physician would cost 57% of the ID specialist, showing a greater cost reduction in this scenario. PrEP-RN costs, meanwhile are sensitive to appointment times. A reduction of these follow-up appointments from 30 to 20 minutes would save $8.29 per patient per visit, or “33.17” per patient per year. This small cost savings constitutes a 22% reduction in the cost of PrEP-RN per annum.

These values remained relatively stable as the years progress for PrEP delivery (see Fig. 2). Due to the low costs of ID specialist follow-up visits, in the second year, the differences in cost between primary care physicians providing PrEP and ID specialists remained relatively unchanged. Whereas the cost per patient for an initiation and one follow-up year for an ID specialist would be $531.31 ($364.95 + $166.36), for a primary care physician, it would be $385.91 ($236.95 + $148.96). For the PrEP-RN nurse, the cost would be $248.80 ($149.28 + $99.52); with time, this difference increases, which is important because people are to take PrEP for as long as they have potential risks, which could range from months to years.

Discussion

The results of this review showed that nurse-led PrEP (PrEP-RN) was the option for PrEP delivery that generated the least overall costs, provided that minimal abnormal results occurred. An important caveat is that cost reductions only occurred for the healthcare system, as, within our jurisdiction, costs associated with physician and nursing access for PrEP are covered through a single-payer remuneration system. In most cases, no such cost coverage occurs for medication.

As previously established, task shifting to nurses from specialists and primary care physicians is often less costly and associated with safe care provision and high patient satisfaction (Fairall et al., 2012; Mdege, Chindove, & Ali, 2013; O’Byrne, MacPherson, Roy, & Orser, 2017). This “task shifting” is not an “off-loading” of care from a provider with more expertise to one with less, but a more appropriate use of various providers (O’Byrne, Phillips, Campbell, Reynolds, & Metz, 2016). Nurses are competent to perform STI assessments, to determine patient’s need for PrEP, to provide relevant counseling, and to undertake appropriate monitoring (Becker, 2017). Following the principles of primary health care (CNA, 2005), PrEP-RN can increase healthcare access using appropriate providers.

Another important caveat to our finding about the costs of PrEP-RN is that the outcomes we identified would depend on rates at which patients did not attend follow-up visits; PrEP-RN costs would also be sensitive to the amount of additional follow-up that might be required based on abnormal STI or kidney function tests. Patients who present for PrEP follow-up with symptoms would also require the nurse to consult with practitioners. As PrEP-RN uses medical directives for testing, result monitoring, and medication provision, these directives would need to be sufficiently robust to capture abnormal results and missed appointments, or the costs would be higher than what we indicated due to the time that would be required for consultation with nurse practitioners and physicians. Pre-established pathways for PrEP-RN could help minimize such consultation time and maintain the low costs we estimated above. In our PrEP-RN clinic, we utilize exactly such pathways to address this issue. Notably, abnormal results would similarly increase costs in the delivery of PrEP by ID specialists and primary care physician. Conversely, shorter follow-up visits for PrEP-RN could reduce costs.

A surprising finding from this review was that, after one year of PrEP delivery, ID specialist physicians would be only marginally more costly than primary care physicians. While this finding is an artifact of low follow-up billing fees for ID specialists in our jurisdiction (MOHLTC, 2018a), it has important implications for future PrEP roll-out in our context. The current remuneration system does not incentivize ID physicians to maintain PrEP provision, while it might entice primary care physicians to do so. This could be beneficial, in that it might increase access in primary care (Hollander & Kadlec, 2015) because there is money attached to PrEP provision. Conversely, immediate healthcare delivery cost savings could arise from forbidding primary care physicians from billing the STI management fee code for any PrEP visit. The problem with proscribing the use of the STI management visit for PrEP is that the financial incentives attached to PrEP would reduce, potentially undermining efforts to increase PrEP delivery by primary care physicians. Careful costs analyses need to evaluate both scenarios. Conversely, one financial incentive to increase PrEP roll-out by primary care physicians would be to allow them to bill the STI management fee code for all PrEP visits, up to the allowable four visits per year. This approach, however, would result in primary care physicians being costlier than ID specialists after the first year of PrEP provision. Nevertheless, the currently slightly lower cost of primary care physicians versus ID specialists highlights the importance of having more PrEP delivery in primary care settings.

For other downsides, the current billing system in Ontario could lead to PrEP initiation by ID specialists and maintenance by primary care physicians, which would yield only minimal cost reductions. While most analyses have identified that PrEP is cost-effective compared to the costs of HIV treatment, efforts to limit additional costs should still be made to maximize cost effectiveness. In our case, the outcome of the ID specialist initiation and primary care physician continuation would be a two-year cost of $513.91, which, per patient, is only $17.40 less expensive than the previously most expensive model (i.e., the ID specialist). While small, with our sample of 40 patients over 10 years, this yields cost savings of $6960, which is the same cost as PrEP-RN for six more patients over the same 10-year period. In this way, PrEP service delivery costs might exceed what would be expected by any single provider. Another limitation to over-involvement of ID specialists in PrEP is that, while these providers would be ideal for PrEP delivery due to expertise in this matter, they would be occupied providing PrEP, which could limit their time to provide other care. Future analyses of PrEP care provision must review such resource allocation implications, and appropriately balance the need to maximize PrEP uptake against minimizing the costs of doing so.

An unsurprising finding is that PrEP medications continue to account for the largest burden of cost for this prevention approach. This is a known issue (Hannaford et al., 2018; Landers & Kapadia, 2017; Peng et al., 2018; Petroll et al., 2017). What this means is that, in the absence of affordable FTC/TDF, PrEP may not be used by those who are most marginalized and at risk for HIV. Research from Toronto highlighted that, among persons at risk for HIV, those at greatest risk for HIV were the least able to afford PrEP (Noor et al., 2018). The issue is that FTC/TDF costs constitute a major barrier to prevention—one that is apt to exacerbate inequities between those who can afford PrEP and those who cannot.

While analyses of provider costs are important, our findings reinforce that the greatest reduction in costs for PrEP would arise from reducing medication costs, as these total $2879.05 for FTC/TDF. For example, the 10-year cost of PrEP-RN provision would be $1044.96 per patient (least expensive option), and this cost would be $1862.19 for ID specialists (most expensive option), yielding a $817.23 cost-saving with PrEP-RN use per patient over 10 years (which would increase to $39,936.21 for the established maximum number needed to treat of 40 patients). By comparison, a 5% reduction in medication costs, equaling savings of $143.96 per patient per year, generates nearly double overall cost reduction per patient on a 10-year horizon (i.e., $1439.60) as would be achieved by having all PrEP delivered by RNs versus ID specialists. Moreover, because overall PrEP access costs disproportionately arise from medication costs, there are only modest savings by switching all first-year initiations from ID specialist (most expense) to PrEP-RN (least expense); indeed, this reduction is only 6.7%, from $3293.65 for the ID specialist to $3013.89 for PrEP-RN, even though the provider costs are only 59.1% lower.

The main issue with this cost-saving relates to who accrues the benefits. For provider costs, in our context, cost-savings would occur for the single-payer publicly funded healthcare system, while for the latter option (medication costs), this would apply to the patient and/or private insurance companies who pay or co-pay medications. As such, for the healthcare system costs, PrEP-RN is the least expensive delivery option, while global analyses of the costs of PrEP per patient warrant further efforts to reduce the costs of FTC/TDF. For global HIV prevention outcomes, efforts to reduce both costs would yield better overall resource savings. This point would similarly apply to publicly funded drug coverage programs.

As a final comment, another way to adjust the cost-effectiveness of PrEP delivery would be to increase the number of HIV infections that would be averted through PrEP use. PrEP delivery that is targeted PrEP at persons at the highest risk for HIV acquisition could achieve such an outcome and reduce the number needed to treat. This aligns with the published literature, in which higher risk samples yielded numbers needed to treat as low as 18 (Buchbinder et al., 2014). In such situations, while the delivery costs per patient would be unchanged, the total costs we estimated would be halved (from a sample of n = 40 to n = 20). Data from Vancouver help identify who to target (Hull, Edward, & Kelley, 2017). Hull et al. (2017) reported the following 100-person-year HIV incidence rates: 3.60 for a person diagnosed with infectious syphilis; 4.60 for a person diagnosed with rectal gonorrhea; 7.14 for a person who uses non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis more than once; and 17.00 for person with a concurrent diagnosis of infectious syphilis and rectal gonorrhea (Hull et al., 2017). Targeting PrEP based on these risk factors could thus increase the number of new HIV infections averted, and, while the total cost per patient would not change, the total cost per averted HIV infection would be reduced. This point requires further research about its operationalization in real-world settings to see if such outcomes would occur.

Conclusion

In this article, we reviewed the costs associated with PrEP delivery by ID specialists, primary care physicians, and nurses in a PrEP-RN clinic. We identified that PrEP-RN was the least costly option for overall care delivery, albeit likely sensitive to patient follow-up and test result outcomes. It would also be sensitive to the amount of time allocated to patient visits. That is, costs for PrEP-RN could increase if many patients did not follow the parameters established in the medical directives that operationalize PrEP-RN, but could decrease if patient visits were shorter than we allocated in our estimates. We also found that, in Ontario, after the first year, PrEP costs in primary care were almost identical to that of ID specialists. Lastly, we identified that the total cost savings that would arise from PrEP-RN would be minimal in the overall costs of PrEP access because FTC/TDF accounted for greater than four-fifths of the PrEP access costs in all scenarios. Our findings thus highlighted that PrEP-RN is an economically viable approach to funding providers for PrEP delivery, but that future efforts should work toward reducing medication costs. Until this time, we fear that PrEP will remain a luxury of the rich and exacerbate the inequities that already exist within HIV incidence.

References

Becker, A. (2017). Nurse-run sexually transmitted infections screening clinics on a university campus. Doctoral Dissertation. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/nursing_dnp_capstone/86/. Accessed 10 Dec 2018.

Blumenthal, J., Jain, S., Mulvihill, E., Sun, S., Hanashiro, M., Ellorin, E., Graber, S., Haubrich, R., & Morris, S. (2018). Perceived versus calculated HIV risk: Implications for pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake in a randomized trial of men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 80(2), e23–e29 epub.

Buchbinder, S. P., Glidden, D. V., Liu, A. Y., McMahan, V., Guanira, J. V., Mayer, K. H., Goicochea, P., & Grant, R. M. (2014). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men and transgendered women: A secondary analysis of a phase 3 randomized controlled efficacy trial. The Lancet, 14(6), 468–475.

Canadian Nurses Association (CNA). (2005). Primary health care: A summary of the issues. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/bg7_primary_health_care_e.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec 2018.

CDC. (2018). Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of hiv infection in the united states – 2017 update. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec 2018.

Drabo, E. F., Hay, J. W., Vardavas, R., Wagner, Z. R., & Sood, N. (2016). A cost-effectiveness analysis of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV among Los Angeles County men who have sex with men. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 63(11), 1495–1504.

Fairall, L., Bachmann, M. O., Lombard, C., Timmerman, V., Uebel, K., Zwarenstein, M., et al. (2012). Task shifting of antiretroviral treatment from doctors to primary-care nurses in South Africa (STRETCH): A pragmatic, parallel, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet, 380(9845), 8–14.

Fu, R., Owens, D. K., & Brandeau, M. L. (2018). Cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies for provision of HIV preexposure prophylaxis for people who inject drugs. AIDS, 32(5), 663–672.

Hannaford, A., Lipshie-Williams, M., Starrels, J. L., Arnsten, J. H., Rizzuto, J., Cohen, P., Jacobs, D., & Patel, V. V. (2018). The use of online posts to identify barriers to and facilitators of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men: A comparison to a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature. AIDS and Behaviour, 22(4), 1080–1095.

Hollander, M. J., & Kadlec, H. (2015). Incentive-based primary care: Cost and utilization analysis. The Permanente Journal, 19(4), 46–56.

Hull, M.W., Edward, J., & Kelley, L., (2017) PEP/PrEP Update – A BC case study. https://www.catie.ca/sites/default/files/pep-prep-bc-casestudy-03272017.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec 2018.

Landers, S., & Kapadia, F. (2017). Preexposure prophylaxis: Adapting HIV prevention models to achieve worldwide access. American Journal of Public Health, 107(10), 1534–1535.

Liu, A., Cohen, S., Follansbee, S., Cohan, D., Weber, S., Sachdev, D., & Buchbinder, S. (2014). Early experiences implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in San Francisco. PLoS Medicine, 11(3), e1001613.

Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC). (2017). Schedule of benefits for laboratory services. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ohip/sob/lab/lab_mn2018.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2018.

Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC). (2018a). Schedule of benefits: Physician services under the Health Insurance Act. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ohip/sob/physserv/sob_master20181115.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2018.

Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC). (2018b). Ontario drug benefits formulary search: Emtricitabine & tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. https://www.formulary.health.gov.on.ca/formulary/results.xhtml?q=truvada&type=2. Accessed 10 Dec 2018.

Ministry of Helath and Long Term Care (MOHLTC). (2014). Ontario drug benefit program: Dispensing fees. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/drugs/programs/odb/opdp_dispensing_fees.aspx. Accessed 10 Dec 2018.

Noor, S. W., Adams, B. D., Brennan, D. J., Moskowitz, D. A., Gardner, S., & Hart, T. A. (2018). Scenes as micro-cultures: Examining heterogeneity of HIV risk behaviour among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Toronto, Canada. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 47(1), 309–321.

O’Byrne, P., Phillips, J. C., Campbell, B., Reynolds, A., & Metz, G. (2016). “Express testing” in STI clinics: Extant literature and preliminary implementation data. Applied Nursing Research, 29, 177–187.

O’Byrne, P., MacPherson, P. A., Roy, M., & Orser, L. (2017). Community-based, nurse-led post-exposure prophylaxis: Results and implications. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 28(5), 505–511.

O’Byrne, P., MacPherson, P. A., Orser, L., Jacob, J. D., & Holmes, D. (2019). PrEP-RN: Clinical considerations and protocols for nurse-led PrEP. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 30(3), 301–311.

O’Byrne, P., Orser, L., Jacob, J. D., Bourgault, A., & Lee, S. R. (2019). Responding to critiques of the Canadian PrEP guidelines: Increasing equitable access through a nurse-led active-offer PrEP service (PrEP-RN). Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 28(1), 5–16.

Peng, P., Su, S., Fairley, C. K., Chu, M., Jiang, S., Zhuang, X., & Zhang, L. (2018). A global estimate of the acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV among men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS and Behaviour, 22(4), 1063–1074.

Petroll, A. E., Walsh, J. L., Owczarzak, J. L., McAuliffe, T. L., Bogart, L. M., & Kelly, J. A. (2017). PrEP awareness, familiarity, comfort, and prescribing experience among US primary care providers and HIV specialists. AIDS and Behaviour, 21(5), 1256–1267.

Tan, D. H. S., Hull, M. W., Yoong, D., Tremblay, C., O’Byrne, P., et al. (2017). Canadian guideline on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 189(47), E1448–E1458.

Walensky, R. P., Jacobsen, M. M., Bekker, L. G., Parker, R. A., Wood, R., Resch, S. C., Horstman, N. K., Freedberg, K. A., & Paltiel, A. D. (2016). Potential clinical and economic value of long-acting preexposure prophylaxis for South African women at high-risk for HIV infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 213(10), 1523–1531.

Yacoub, R., Nadkami, G. N., Weikum, D., Konstantindis, I., Boueih, A., Grant, R. M., Mugwayna, K. K., Baeten, J. M., & Wyatt, C. M. (2016). Elevations in serum creatinine with tenofovir-based pre-exposure prophylaxis: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 71(4), e115–e118.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN) for funding our PrEP-RN clinic. The authors would like to graciously acknowledge the OHTN for funding Patrick O’Byrne’s Research Chair in Public Health & HIV Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Byrne, P., Orser, L. & Jacob, J.D. The Costs of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Care Delivery: Comparing Specialists, Primary Care, and PrEP-RN. Sex Res Soc Policy 17, 326–333 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00391-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00391-3