Abstract

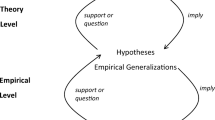

In the last decade Robert Barnard and Joseph Ulatowski have conducted a number of experimental studies in order to better understand the ordinary notion of truth. In this paper I critically engage their ecological approach to the study of truth, and argue for a wider perspective on how truth should be empirically studied: in addition to the experimental data that they emphasize and collect, there should also be a substantial observational element to conceptual ecology. I then critically evaluate the conclusions they draw from their data, as they relate to correspondence, pluralism, and objectivity. Along the way, I offer suggestions for future lines of research for a more expansive and effective ecological exploration of truth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Which is not to say that thought experiments never play a role in the theory of truth. For instance, they can be used to generate potential counterexamples to various substantivist theories, as I discuss in Sect. 3.1.

Devitt (2012) also advocates the use of corpora within experimental philosophy.

I leave it as an open, historical question how traditional ordinary language philosophy (and particularly the ordinary language philosophy focused on truth, such as Strawson 1949 and 1950 and Austin 1950) fits in here, and how systematic its concern with ordinary language was. For recent accounts of how experimental methods can inform ordinary language methods, see Fischer 2023.

See, e.g., Reuter and Brun 2022, which talks about the concept of truth, not the word, being ambiguous.

See Chaps. 1 and 2 of Machery 2009 for an overview of how concepts are used in psychology and philosophy.

Likewise, if ‘true’ is ambiguous (as per Kölbel 2013), then we ourselves express different concepts when we deploy the different meanings—in which case it’s misleading to speak of the concept of truth: there is no single concept expressed by ‘true’.

Naturally, plenty in this paragraph about the theoretical role of concepts is debatable, but hardly idiosyncratic. My aim is to make plain what I (and I presume much of the extant theory of truth) am presuming about the role of concepts in philosophy. Note that Barnard and Ulatowski appear to endorse this general line of thought (2021: S727).

Participants were asked to judge agreement by way of a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Barnard and Ulatowski report the finding as follows: “In the Anna condition, the mean response to ST was 2.81 out of 5. In the Bruno condition, the mean response to ST was 3.63 out of 5. This difference was statistically significant (N = 83, t (81) = − 2.943, p < .004)” (2013: 630).

Note that Barnard and Ulatowski also connect the notion of correspondence to Aristotle’s dictum that “a truth is a statement of that which is that it is, or of that which is not that it is not” (Aristotle 1966: 70; 1011b25-28). Deflationists are happy to endorse that claim, or even see it as an early statement of their view.

They also found some variation with respect to gender in a related experiment.

See also Wyatt 2018: 178.

In their 2019, Barnard and Ulatowski report on a different study that does provide evidence of folk support for the weaker sense of correspondence I’ve identified here.

It could also be useful to test the acceptability of what Azzouni calls “Putnam modals”, such as ‘The sentence ‘The rug is green’ might be warrantedly assertible, even though the rug is not green’ (2000: 111). Someone who agreed with that, but disagreed with ‘It might not be true that the rug is green, even though the rug is green’ is someone who likely abides by what philosophers have in mind by the correspondence intuition.

Of course, it’s an open question what the actual implications are of any particular substantive view of truth.

Ulatowski presents data he collected with Barnard that suggest there is little folk support for pragmatic perspectives on truth (2017: 106–111).

I contest this particular point (see Asay 2024), but will assume it’s correct for the time being.

See Wyatt 2013 for a critical examination of the role of domains in alethic pluralism.

This I take to be the major takeaway from the mountain of qualitative data collected in Næss 1938b.

In the month I surveyed, I found 59 instances of ‘true for’ (so about two per day, on average), none of which fit the relativistic sense intended for (U). Most were of the “indexical” variety, and others were not genuine uses of ‘true for’, as in ‘This is a dream come true for Sophie’.

At one point, Barnard and Ulatowski suggest that people might be reading (U) as saying “When I think a claim is true, everyone must agree with me”, though I find this rather implausible (2021: S727). They must agree with me on pain of what? Later, though, they seem to adopt the ‘believed by’ interpretation: “For the non-philosopher to agree with a statement like [‘It is true for everyone that the Red Sox have a deeper bullpen than do the Yankees’], or U as it was in the experiment, is for them to hold that everyone agrees with [i.e., believes] the statement mentioned therein” (2021: S728).

Suppose two groups of people, say, a collection of bankers and a set of riverboat captains, are asked to interpret ‘Pat is by the bank’, and they systematically diverge in their interpretation. The simplest explanation for the divergence is not that the groups have competing conceptual schemes.

References

Alston, William P. 2002. Truth: concept and property. In What is truth?, ed. Richard Schantz, 11–26. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Aristotle. 1966. Metaphysics. Trans. Hippocrates G. Apostle. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Asay, Jamin. 2013. The primitivist theory of truth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Asay, Jamin. 2024. Arne Næss’s experiments in truth. Erkenntnis 89: 545–566.

Atkins, B. T. Sue, and Michael Rundell. 2008. The Oxford guide to practical lexicography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Austin, J. L. 1950. Truth. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 24: 111–128.

Azzouni, Jody. 2000. Knowledge and reference in empirical science. London: Routledge.

Barnard, Robert, and Joseph Ulatowski. 2013. Truth, correspondence, and gender. Review of philosophy and psychology 4: 621–638.

Barnard, Robert, and Joseph Ulatowski. 2019. Does anyone really think that [φ] is true if and only if φ? In Advances in experimental philosophy of logic and mathematics, eds. Andrew Aberdein and Matthew Inglis, 145–171. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Barnard, Robert, and Joseph Ulatowski. 2021. The objectivity of truth, a core truism? Synthese 198: S717–S733.

Bar-On, Dorit, and Keith Simmons. 2007. The use of force against deflationism: assertion and truth. In Truth and speech acts: studies in the philosophy of language, eds. Dirk Greimann and Geo Siegwart, 61–89. London: Routledge.

Barsalou, Lawrence W. 1999. Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 22: 577–660.

Barsalou, Lawrence W., and Jesse J. Prinz. 1997. Mundane creativity in perceptual symbol systems. In Creative thought: an investigation of conceptual structures and processes, eds. Thomas B. Ward, Steven M. Smith, and Jyotsna Vaid, 267–307. American Psychological Association.

Davidson, Donald. 1987. Knowing one’s own mind. Proceedings and addresses of the american philosophical association 60: 441–458.

Devitt, Michael. 2012. Whither experimental semantics? Theoria 73: 5–36.

Égré, Paul. 2021. Half-truths and the liar. In Modes of truth: The unified approach to truth, modality, and paradox, eds. Carlo Nicolai, and Johannes Stern, 18–40. New York: Routledge.

Fischer, Eugen. 2023. Critical ordinary language philosophy: a new project in experimental philosophy. Synthese 201(102): 1–34.

Goldman, Alvin I. 1976. Discrimination and perceptual knowledge. Journal of Philosophy 73: 771–791.

Henderson, Jared. 2021. Truth and gradability. Journal of Philosophical Logic 50: 755–779.

Horwich, Paul. 1990. Truth. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Horwich, Paul. 2010. Truth-meaning-reality. Oxford: Clarendon.

Kant, Immanual. 1996. On a supposed right to lie from philanthropy. In Practical philosophy, trans. A. W. Wood, eds. Mary J. Gregor, 605–616. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kölbel, Max. 2013. Should we be pluralists about truth? In Truth and pluralism: current debates, eds. Nikolaj J.L.L. Pedersen and Cory D. Wright, 278–297. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lynch, Michael P. 2009. Truth as one and many. Oxford: Clarendon.

Machery, Edouard. 2009. Doing without concepts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mankowitz, Poppy. 2023. Not half true. Mind 132: 84–112.

Moltmann, Friederike. 2021. Truth predicates, truth bearers, and their variants. Synthese 198: S689–S716.

Næss, Arne. 1938a. Common-sense and truth. Theoria 4: 39–58.

Næss, Arne. 1938b. Truth as conceived by those who are not professional philosophers. Oslo: Jacob Dybwad.

Næss, Arne. 1953. An empirical study of the expressions “true”, “perfectly certain” and “extremely probable”. Oslo: Jacob Dybwad.

Reuter, Kevin, and Georg Brun. 2022. Empirical studies on truth and the project of re-engineering truth. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 103: 493–517.

Sosa, Ernest. 1993. The truth of modest realism. Philosophical Issues 3: 177–195.

Strawson, P. F. 1949. Truth. Analysis 9: 83–97.

Strawson, P. F. 1950. Truth. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 24: 129–156.

Tarski, Alfred. 1944. The semantic conception of truth: And the foundations of semantics. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 4: 341–376.

Thomson, Judith Jarvis. 1971. A defense of abortion. Philosophy and Public Affairs 1: 47–66.

Thomson, Judith Jarvis. 1985. The trolley problem. Yale Law Journal 94: 1395–1415.

Ulatowski, Joseph. 2017. Commonsense pluralism about truth: An empirical defence. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ulatowski, Joseph. 2018. Is there a commonsense semantic conception of truth? Philosophia 46: 487–500.

Ulatowski, Joseph, and Jeremy Wyatt. 2023. From infants to great apes: False belief attribution and primitivism about truth. In Experimental philosophy of language: Perspectives, methods, and prospects, ed. David Bordonaba-Plou, 263–286. Cham: Springer.

Wyatt, Jeremy. 2013. Domains, plural truth, and mixed atomic propositions. Philosophical Studies 166: S225–S236.

Wyatt, Jeremy. 2018. Truth in English and elsewhere: An empirically-informed functionalism. In Pluralisms in truth and logic, eds. Jeremy Wyatt, Nikolaj J. L. L. Pedersen, and Nathan Kellen. 169–196. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to Max Deutsch and the referees for the journal for their contributions to this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Asay, J. Experimenting with Truth. Rev.Phil.Psych. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-024-00728-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-024-00728-x