Abstract

Moral judgments, we expect, ought not to depend on luck. A person should be blamed only for actions and outcomes that were under the person’s control. Yet often, moral judgments appear to be influenced by luck. A father who leaves his child by the bath, after telling his child to stay put and believing that he will stay put, is judged to be morally blameworthy if the child drowns (an unlucky outcome), but not if his child stays put and doesn’t drown. Previous theories of moral luck suggest that this asymmetry reflects primarily the influence of unlucky outcomes on moral judgments. In the current study, we use behavioral methods and fMRI to test an alternative: these moral judgments largely reflect participants’ judgments of the agent’s beliefs. In “moral luck” scenarios, the unlucky agent also holds a false belief. Here, we show that moral luck depends more on false beliefs than bad outcomes. We also show that participants with false beliefs are judged as having less justified beliefs and are therefore judged as more morally blameworthy. The current study lends support to a rationalist account of moral luck: moral luck asymmetries are driven not by outcome bias primarily, but by mental state assessments we endorse as morally relevant, i.e. whether agents are justified in thinking that they won’t cause harm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Mitch prepares a bath for his 2-year-old son, who is standing by the tub, when the phone rings in the next room. Mitch tells his son to stay put, fully believing his son will do so. Mitch leaves the room for a moment. If, when Mitch returns, his son is in the tub, face down in the water, we would judge Mitch’s behavior to be negligent and morally blameworthy. Mitch would also face serious legal consequences. By contrast, if, when Mitch returns, his son is still waiting outside the tub, we would not find much fault with Mitch’s parenting skills, and certainly not to the same extent as in the first scenario. Many moral judgments share this asymmetry: the agent is judged more morally blameworthy when his actions end in a bad outcome than in a neutral one (Cushman 2008; Baron and Hershey 1988; Nagel 1979; Williams 1982). Even children as young as 3 years old make different moral and social judgments about lucky people, or beneficiaries of uncontrollable good events (e.g., finding $5 on the sidewalk) compared to unlucky people, or victims of uncontrollable bad events (e.g., the raining out of a soccer game; Olson et al. 2006, 2008). Yet these judgments may also seem paradoxical. After all, in our original example, everything from the agent’s perspective was exactly the same, including what the agent thought would happen, and what the agent himself did. In general, we expect that morality should not depend on luck.

What accounts for the difference in moral judgments? In most examples of “moral luck”, two factors distinguish the lucky agent from the unlucky agent. First, the outcome in the unlucky case is worse (e.g., drowning) than in the lucky case (e.g., bathing). Second, the unlucky agent’s belief (e.g., that his son will stay put) is false, whereas this same belief is true for the lucky agent. False beliefs and bad outcomes have typically been confounded in standard moral luck scenarios from philosophy (Nagel 1979; Williams 1982). The unlucky agent holds a false belief that leads to a bad outcome, while the lucky agent holds a true belief that leads to a neutral (or, at least, less bad) outcome. Therefore, classic moral luck asymmetries between the unlucky agent (false belief, bad outcome) and the lucky agent (true belief, neutral outcome) could be due either to the difference between false and true beliefs or to the difference between bad and neutral outcomes.

As introduced by Nagel (1979) and Williams (1982), traditional philosophical accounts suggest that moral luck reflects the direct influence of the outcome on moral judgments. On these accounts, bad outcomes lead directly to more moral blame, independent of other facts about the agent and the action. Recent work in psychology provides a natural way to explain why bad outcomes would lead directly to more moral blame. Observers might experience an aversive emotional response to the child’s death, independent of any assessment of the father’s beliefs and intentions, causing them to blame the unlucky father more (Greene et al. 2001, 2004; Haidt 2001).

In the current paper, we propose an alternative account: moral luck depends primarily on observers’ assessment of the beliefs and intentions of the unlucky agent. That is, people’s different judgments of lucky and unlucky agents are due primarily to the difference between true and false beliefs, rather than neutral and bad outcomes. Specifically, we hypothesize that (1) because it is false, the unlucky agent’s belief is perceived to be less justified than the lucky agent’s belief, and (2) the justification of the unlucky agent’s belief influences moral judgment. For example, in the case that Mitch’s son turns out to be disobedient, observers may feel that Mitch’s false belief (that his son would be obedient) was less justified, and therefore judge Mitch himself more blameworthy. If so, the proposed influence of falseness on justification and therefore on moral blame may be considered rational or irrational. Some accounts suggest that false beliefs should properly be considered less justified and more blameworthy (Richards 1986; Rosebury 1995). Others would view this inference as an example of an irrational “hindsight bias” (Royzman and Kumar 2004): facts that turn out to be true seem to have been more obvious all along. Our study cannot distinguish between these normative accounts of moral judgments. We simply investigated whether, descriptively, unlucky agents are judged to be more morally blameworthy because their false beliefs are judged to be less justified.

To separately test for the contributions of false beliefs and bad outcomes to “moral luck”, we developed a new kind of scenario featuring “extra lucky” agents. Extra lucky agents hold the same false beliefs as the unlucky agents, but—due to an extra stroke of good luck—the bad outcome does not occur. For example, imagine that Mitch returns and finds his son already in the tub, not face down in the water but simply enjoying his bath. By comparing agents with true, false, and “extra lucky” false beliefs (who produce neutral, negative, and neutral outcomes, respectively), we could therefore test the separate contributions of false beliefs and negative outcomes to the phenomenon of moral luck. We hypothesized that in the “extra lucky” case Mitch would be judged morally blameworthy just because his belief was false, even though no bad outcome occurred.

This hypothesis generated four specific predictions. First, observers should judge false beliefs to be less justified than the corresponding true beliefs. Second, observers should assign more moral blame to agents who act on false beliefs than agents who act on true beliefs, even when the beliefs are based on the same reasons, and result in the same neutral outcomes. Third, the influence of false beliefs on moral judgments should be mediated by judgments of whether the false belief is justified. And, finally, we hypothesized that whether or not the agent had a false belief should account for more “moral luck” than whether or not a bad outcome occurred.

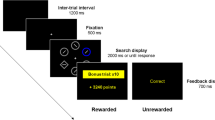

To test these predictions, we presented participants with 54 moral scenarios. There were nine variations of each scenario, and each participant saw only one variation of each scenario (Fig. 1). The agent’s belief was identical across conditions. The reason for the agent’s belief varied across conditions: the reason could be good, bad, or unspecified. For example, Mitch could believe that his son will listen because his son always does what he is told (good reason), or in spite of the fact that he never does what he is told (bad reason). In a third condition (unspecified reason), more similar to previous philosophical examples, the scenario did not state the agent’s reason (good or bad) for the belief. The agent’s action was identical across all variations (e.g., leaving his son alone by the tub), but the outcome of the action could be neutral (e.g., son is fine) or bad (e.g., son drowns), and the belief could be true (e.g., son stays put) or false (e.g., son does not stay put). The novel “extra lucky” condition occurred when the belief was false, but the outcome was neutral. In two behavioral experiments and one fMRI experiment, participants judged whether the agent had good reason for his or her belief (i.e. belief justification judgments) and/or how much moral blame the agent deserved for the action (i.e. moral blameworthiness judgments).

Experimental stimuli and design. Stimuli consisted of 54 scenarios providing information about (1) the background (identical across conditions), (2) the agent’s belief (identical across conditions) and whether the reason for the agent’s belief is bad, good or unspecified, and (3) the agent’s action and the outcome (bad or neutral), independently rendering the agent’s belief true or false. The question was presented alone on the screen for 4 s, in the fMRI experiment. Participants were asked about the moral blameworthiness of the protagonist in the fMRI experiment and Behavioral Experiment 2. Participants were asked about the reasonableness or justification of the protagonist’s belief in Behavioral Experiments 1 and 2

In addition to behavioral analyses, we tested whether activity in brain regions implicated in mental state reasoning (e.g., Ciaramidaro et al. 2007; Fletcher et al. 1995; Gallagher et al. 2000; Gobbini et al. 2007; Ruby and Decety 2003; Saxe and Kanwisher 2003; Vogeley et al. 2001) differentiates between true and false beliefs, good or bad reasons, bad and neutral outcomes. Truth and justification are properties of the belief that are relevant for moral judgment, and might therefore lead to differential activation while participants are reading about the belief. By contrast, outcomes are distinct from beliefs but may nevertheless provoke observers to pay greater attention to the content and justification of the belief during and even after the moral judgment (Kliemann et al. 2008; Alicke 2000).

2 Method

2.1 Behavioral Experiment 1

Twenty-four college undergraduates participated in the first behavioral experiment. Stimuli consisted of 54 scenarios providing information about (1) the background (identical across conditions), (2) the agent’s belief (identical across conditions) and whether the agent’s reason for the belief is bad, good or unspecified, and (3) the agent’s action and the outcome (bad or neutral), independently rendering the agent’s belief true or false (Fig. 1). Stories were presented in three cumulative segments: first, the background for 6 s, then the belief and reason for 4 s, and finally the action and outcome for 6 s. Stories were presented in a pseudorandom order; conditions were counterbalanced across runs and participants. Participants responded to a question about belief justification: “Does the agent have good reason for [his or her belief]?” on a 7-point scale (1-not at all, 7-very much).

2.2 Behavioral Experiment 2

A new group of forty-two college undergraduates read the same scenarios and responded to the belief justification question (as above) as well as to a second moral blameworthiness question: “How morally blameworthy is [the agent] for [performing the action]?” on a 7-point scale (1-not at all, 7-very much). The order of these questions was counterbalanced across participants.

2.3 FMRI Experiment

A new group of nineteen neurologically normal, right-handed adults (aged 18–25, ten women) participated in the fMRI experiment. FMRI data from two female subjects were not included in the analyses due to excessive head motion; behavioral data were analyzed from all nineteen subjects. Participants were scanned at 3T (at the MIT scanning facility) using 26 4-mm-thick near-axial slices covering the whole brain. Standard echoplanar imaging procedures were used (TR = 2 s, TE = 40 msec, flip angle 90°).

Stimuli and presentation were identical to the behavioral experiments as described above, with two exceptions. First, rest blocks (14 s) were interleaved between stories. Second, participants responded only to one question: “How morally blameworthy is [the agent] for [performing the action]?” on a 4-point scale (1-not at all, 4-very much), using a button press. Nine stories were presented per run for a total of six runs.

In the same scan session, all participants also participated in four runs of a mental state reasoning (or theory of mind) localizer task. This task contrasted stories requiring inferences about mental state representations (e.g., thoughts, beliefs) versus physical representations (e.g., maps, signs, photographs). Stimuli and presentation were as described in Saxe and Kanwisher 2003. Replicating previous results, regions of interest (ROIs) for mental state reasoning were identified in individual subjects: right (R) and left (L) temporo-parietal junction (TPJ), precuneus (PC), dorsal (D) and ventral (V) medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC).

2.4 FMRI Analysis

MRI data were analyzed using SPM2 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and custom software. Each subject’s data were motion corrected and normalized onto a common brain space (Montreal Neurological Institute, MNI, template). Data were smoothed using a Gaussian filter (full width half maximum = 5 mm) and high-pass filtered during analysis. A slow event-related design was used and modeled using a boxcar regressor to estimate the hemodynamic response for each condition. An event was defined as a single story, the event onset defined by the onset of text on screen.

Both whole-brain and tailored regions of interest (ROI) analyses were conducted. Five ROIs were defined for each subject individually based on a whole brain analysis of the independent localizer experiment, and defined as contiguous voxels that were significantly more active (p < 0.001, uncorrected, k > 5) while the subject read belief stories, as compared with photograph stories. All peak voxels are reported in MNI coordinates.

The responses of these regions of interest were then measured while subjects read moral stories from the current study. Within the ROI, the average percent signal change (PSC) relative to rest (PSC = 100× raw BOLD magnitude for (condition−rest)/raw BOLD magnitude for rest) was calculated for each condition at each time point (averaging across all voxels in the ROI and all blocks of the same condition, Poldrack 2006). We then averaged together the time points within the belief phase (10–14 s after story onset, to account for hemodynamic lag) and within the moral judgment phase (20–24 s after story onset) to get two PSC values for each ROI in each subject. These values were used in all reported analyses below.

3 Results

We analyzed the effects of the agent’s reason for the belief (good, unspecified, bad), the truth of the belief (true, false), and the outcome of the action (neutral, bad) on participants’ judgments of moral blameworthiness, judgments of belief justification, and neural responses in each region of interest (ROI). Because the conditions were not completely crossed (i.e. there was no condition in which the belief was true, but the outcome negative), the effects of truth and outcome were analyzed separately in all subsequent analyses. The effect of truth was measured by comparing the conditions with neutral outcomes (lucky agents’ true beliefs and extra lucky agents’ false beliefs). The effect of outcome was measured by comparing the conditions with false beliefs (extra lucky neutral outcomes and unlucky negative outcomes).

3.1 Moral Blameworthiness Judgments (fMRI Experiment)

Subjects’ judgments of moral blameworthiness (Fig. 2) were affected by the agent’s reason for the belief (good, unspecified, bad), the truth of the belief (true, false), and the outcome of the action (neutral, bad).

Moral Blameworthiness Judgments (fMRI Experiment). In the fMRI experiment, judgments were made on a 4-point scale (1=not at all blameworthy, 4=very blameworthy). Left, middle, and right clusters correspond to good, unspecified, and bad reasons respectively. Left-most (unspotted) bars marked “T” correspond to true beliefs. Right (spotted) bars marked “F” correspond to false beliefs. Left light bars correspond to neutral outcomes. Right shaded bars correspond to bad outcomes. Asterisks mark significant differences (p < 0.05)

A 3 [Reason: bad vs. unspecified vs. good] ×2 [Truth: true vs. false] repeated measures ANOVA of the neutral outcome conditions, revealed main effects of reason (F(1, 17) = 8.9 p = 0.002, partial h 2 = 0.51) and truth (F(1, 18) = 86.1 p = 2.8 × 10−8, partial h 2 = 0.83) on judgments of moral blameworthiness. The interaction between reason and truth was not significant (F(1, 18) = 1.0 p = 0.37, partial h 2 = 0.11). Even when all the outcomes were neutral, agents with bad reasons were judged as more blameworthy than agents with unspecified reasons (t(18) = 2.7 p = 0.01), and agents with unspecified reasons were judged as more blameworthy than agents with good reasons (t(18) = 3.5 p = 0.002). Agents with false beliefs were judged as more blameworthy than agents with true beliefs across the reason conditions: when agents’ reasons for their beliefs were good (t(18) = 5.7 p = 2.2 × 10−5), unspecified (t(18) = 3.8 p = 0.001), and bad (t(18) = −6.1 p = 1.0 × 10−5).

A 3 [Reason: bad vs. unspecified vs. good] ×2 [Outcome: neutral vs. bad] repeated measures ANOVA of the false belief conditions, revealed main effects of reason (F(1, 17) = 11.4 p = 0.001, partial h2 = 0.57) and outcome (F(1, 18) = 5.4 p = 0.03, partial h 2 = 0.23) on judgments of moral blameworthiness. The interaction between reason and outcome was not significant (F(1, 18) = 0.90 p = 0.43, partial h 2 = 0.10). When their beliefs were false, agents with good reasons were still judged to be less morally blameworthy than agents with unspecified reasons (t(18) = 3.4 p = 0.003) or bad reasons (t(18) = 4.8 p = 1.5 × 10−4). The difference in moral judgments of agents with unspecified versus bad reasons did not reach significance (t(18) = 1.6 p = 0.12). Although there was a significant main effect of outcome in the overall analysis, in pairwise comparisons agents causing bad outcomes were judged significantly more morally blameworthy than agents causing neutral outcomes only when agents had bad reasons for their beliefs (t(18) = 2.1 p = 0.046). The effect of bad outcomes did not reach significance when agents had unspecified reasons (t(18) = 1.5 p = 0.15) or good reasons (t(18) = 1.5 p = 0.15) for their beliefs.

Participants’ reaction times to make these judgments were not affected by the agent’s reason, the truth of their beliefs, or the outcome of their actions.

3.2 Belief Justification Judgments (Behavioral Experiment 1)

As predicted, subjects’ judgments of belief justification (Fig. 3) were influenced by the agent’s reason for the belief (good, unspecified, bad) and the truth of the belief (true, false). A 3 [Reason: bad vs. unspecified vs. good] ×2 [Truth: true vs. false] repeated measures ANOVA of the neutral outcome conditions, revealed significant main effects of reason (F(1, 22) = 118.5 p = 1.6 × 10−12, partial h 2 = 0.92) and truth (F(1, 23) = 31,9 p = 9.4 × 10−6, partial h 2 = 0.58). Whether the belief was true or false mattered more for belief justification judgments, however, if the agent had a good or unspecified reason for his or her belief; if the agent had a bad reason for his or her belief, participants judged the belief to be unjustified even if it turned out to be true, producing a significant interaction between reason and truth (F(1, 22) = 6.4 p = 0.006, partial h 2 = 0.37). In pairwise comparisons, when the outcomes were all neutral, agents with good reasons were judged as having more justified beliefs than agents with unspecified reasons (t(23) = 5.7 p = 7.7 × 10−6), and agents with unspecified reasons were judged as having more justified beliefs than agents with bad reasons (t(23) = 4.7 p = 1.1 × 10−4). False beliefs were judged to be less justified than true beliefs when the reasons for the beliefs were good (t(23) = 5.7 p = 7.8 × 10−6) or unspecified (t(23) = 4.0 p = 0.001). However, false beliefs were only marginally less justified than true beliefs when the agent had a bad reason for the beliefs (t(23) = 1.9 p = 0.07).

Belief Justification Judgments (Behavioral Experiment 1). Judgments were made on a 7-point scale (1=not at all reasonable/justified, 7=very reasonable/justified). Left, middle, and right clusters correspond to good, unspecified, and bad reasons respectively. Left-most (unspotted) bars marked “T” correspond to true beliefs. Right (spotted) bars marked “F” correspond to false beliefs. Left light bars correspond to neutral outcomes. Right shaded bars correspond to bad outcomes. Asterisks mark significant differences (p < 0.05)

The outcome of the action (neutral vs. bad) had a small effect on judgments of belief justification (Fig. 3). A 3 [Reason: bad vs. unspecified vs. good] ×2 [Outcome: neutral vs. bad] repeated measures ANOVA of the false belief conditions, revealed a significant main effect of reason (F(1, 22) = 60.8 p = 1.1 × 10−9, partial h 2 = 0.85) and a marginal effect of outcome (F(1, 23) = 3.8 p = 0.06, partial h 2 = 0.14), with no interaction (F(1, 22) = 0.99 p = 0.39, partial h 2 = 0.08). For the false belief conditions, beliefs based on good reasons were judged more justified than beliefs based on unspecified reason (t(23) = 5.8 p = 6.1 × 10−6), and beliefs based on unspecified reasons were judged more justified than beliefs with bad reasons (t(23) = 4.6 p = 1.2 × 10−4). Similar to the pattern for moral blame judgments, when agents had bad reasons for their false beliefs, those beliefs were judged significantly less justified when they led to bad versus neutral outcomes (t(23) = 2.3 p = 0.03). In other words, the same false beliefs based on the same bad reasons were judged to be less justified when they led to bad outcomes (as opposed to neutral outcomes). This effect of bad outcomes on belief justification judgments was limited to bad reasons, though; there was no effect of bad outcomes on belief justification judgments when agents had unspecified reasons (t(23) = 1.3 p = 0.22) or good reasons (t(23) = 0.83 p = 0.41) for their beliefs.

3.3 Behavioral Experiment 2

Forty-two new participants read the same set of fifty-four moral scenarios but made both judgments of moral blameworthiness and judgments of belief justification for each scenario. This design allowed us to accomplish two goals. First, this experiment allowed us to examine the relationship among the different variables by mediation analyses, specifically, to determine (1) whether the influence of reason on moral judgments was mediated by the influence of reason on belief justification judgments, (2) whether the influence of truth on moral judgments was mediated by the influence of truth on belief justification judgments, and (3) whether the influence of outcome on moral judgments was mediated by the influence of outcome on belief justification judgments, or, alternatively, whether the direct influence of outcome on moral judgments mediated the influence of outcome on belief justification judgments. Second, this behavioral experiment, together with the moral judgment data collected in the fMRI experiment, allowed us to test whether false beliefs contribute more to moral luck than bad outcomes.

We first replicated the general pattern of effects reported in the initial behavioral and fMRI experiments. For moral blameworthiness judgments, a 3 [Reason: bad vs. unspecified vs. good] ×2 [Truth: true vs. false] repeated measures ANOVA of the neutral outcome conditions, revealed main effects of reason (F(2, 40) = 11.2 p < 0.001, partial h 2 = 0.36) and truth (F(1, 41) = 92.6 p < 0.001, partial h 2 = 0.69), and no interaction. A 3 [Reason: bad vs. unspecified vs. good] ×2 [Outcome: neutral vs. bad] repeated measures ANOVA of the false belief conditions, revealed main effects of reason (F(2, 40) = 14.1 p < 0.001, partial h 2 = 0.41) and outcome (F(1, 41) = 29.7 p < 0.001, partial h 2 = 0.42), and no interaction.

For belief justification judgments, a 3 [Reason: bad vs. unspecified vs. good] ×2 [Truth: true vs. false] repeated measures ANOVA of the neutral outcome conditions, revealed main effects of reason (F(2, 37.4) = 11.2 p < 0.001, partial h 2 = 0.66) and truth (F(1, 40) = 19.0 p < 0.001, partial h 2 = 0.32). However, the interaction between effects of reason and truth, in Behavioral Experiment 1, was not replicated in Behavioral Experiment 2; even beliefs based on bad reasons were judged to be more justified when they were true than when they were false. A 3 [Reason: bad vs. unspecified vs. good] ×2 [Outcome: neutral vs. bad] repeated measures ANOVA of the false belief conditions, revealed main effects of reason (F(2, 40) = 48.6 p < 0.001, partial h 2 = 0.71) and outcome (F(1, 41) = 9.2 p = 0.004, partial h 2 = 0.18), and no interaction.

We were then able to conduct mediation analyses to look at the relationship between condition variables (reason, truth, and outcome) and participants’ judgments of moral blameworthiness and belief justification.

First, we examined the relationship between reason (good vs. unspecified vs. bad reason), moral judgments, and belief justification judgments. The conditions for a mediation analysis were met: (1) the difference in reason had a significant effect on both moral judgments and belief justification judgments, as noted above, and (2) moral judgments and belief justification judgments were themselves significantly correlated (r = −0.336, p < 0.001). As predicted, a Sobel test showed that the effect of reason on moral judgments was mediated by the effect of reason on belief justification judgments (Z = −4.78, p < 0.00001). In other words, part of the effect of reason on moral judgments was due to the effect of reason on belief justification judgments (Fig. 4).

A Model of the Cognitive Inputs. Reason (bad, unspecified, good reasons) and truth (false versus true beliefs) influence judgments of belief justification, which influence moral blameworthiness judgments (blue and purple arrows). Outcome (bad versus neutral outcomes) directly influences moral blameworthiness judgments, which in turn influence belief justification judgments (red arrows)

Second, we examined the relationship between truth (true vs. false beliefs), moral judgments, and belief justification judgments. The conditions for a mediation analysis were met: (1) the difference in truth had a significant effect on both moral judgments and belief justification judgments, as noted above, and (2) moral judgments and belief justification judgments were themselves significantly correlated (r = −0.276, p < 0.001). As predicted, a Sobel test showed that the effect of truth on moral judgments was mediated by the effect of truth on belief justification judgments (Z = −2.50 p = 0.01). In other words, part of the effect of truth on moral judgments was due to the effect of truth on belief justification judgments (Fig. 4).

Third, we examined the relationship between outcome condition (bad vs. neutral), moral judgments, and belief justification judgments. The conditions for a mediation analysis were met: (1) the difference in outcome condition had a significant effect on both moral judgments and belief justification judgments, as noted above, and (2) moral judgments and belief justification judgments were themselves significantly correlated (r = −0.224, p < 0.001). A Sobel test provided no evidence for the notion that the effect of outcome on moral judgments was mediated by the effect of outcome on belief justification judgments (Z = 1.77 p = 0.08). Instead, the effect of outcome on belief justifications was mediated by the effect of outcome on moral judgments (Z = −2.58 p = 0.01). In other words, part of the effect of outcome on belief justification judgments was due to the direct effect of outcome on moral judgments (Fig. 4).

Finally, we tested our prediction that false beliefs account for more moral luck than bad outcomes. To do so, we computed two difference scores. First, for the effect of false beliefs, we calculated the difference in moral blame for extra lucky agents (false beliefs, neutral outcomes) versus lucky agents (true beliefs, neutral outcomes). Second, for the effect of bad outcomes, we calculated the difference in moral blame for unlucky agents (false beliefs, bad outcomes) versus extra lucky agents (false beliefs, neutral outcomes). Paired-samples t-tests showed that the effect of false beliefs was greater than the effect of bad outcomes (fMRI experiment, t(18) = −3.3 p = 0.004, Behavioral Experiment 2, t(41) = −1.8 p = 0.07).

3.4 fMRI Results

A whole-brain random effects analysis of the data replicated results of previous studies using the same task (Saxe and Kanwisher 2003), revealing a higher BOLD response during stories describing mental states such as thoughts and beliefs, as compared to stories describing physical (non-mental) states, in the RTPJ, LTPJ, PC, DMPFC, and VMPFC (p < 0.001, uncorrected, k > 10). ROIs were identified in individual subjects at the same threshold (Table 1): RTPJ (identified in 17 of 17 subjects), LTPJ (17/17), PC (17/17), DMPFC (13/17), and VMPFC (10/17).

We observed a robust response in the ROIs when the belief and the agent’s reason for the belief were presented. However, we found no effect of condition (bad vs. unspecified vs. good reason) on the response in any ROI during the belief presentation. That is, while participants were reading about beliefs, there was a large and robust response (especially in the RTPJ and LTPJ), independent of whether the belief was justified or unjustified (Fig. 5).

Average percent signal change (PSC) in RTPJ region of interest (ROI) over time. Functional localizer results (top left): brain regions where the BOLD signal was higher for (nonmoral) stories about mental states than (nonmoral) stories about physical representations (N = 17, random effects analysis, p < 0.001, uncorrected, k > 20). These data were used to define ROIs, including the RTPJ. The RTPJ ROI was not sensitive to reason (top) or truth (middle). By contrast, the RTPJ was sensitive to outcome, showing a higher response for bad outcomes (bottom). Asterisk marks significant differences in PSC during moral judgment (p < 0.05)

Later in the trial, while participants made moral judgments (and the belief information was no longer on the screen), we observed a small but significant response in the RTPJ and LTPJ for bad outcomes versus neutral outcomes (3 [Reason] ×2 [Outcome] ANOVA, main effect of outcome, RTPJ: F(1, 16) = 4.33 p = 0.05, partial h 2 = 0.21; LTPJ: F(1, 16) = 16.2 p = 0.001, partial h 2 = 0.50; Fig. 5). There was also a unpredicted effect of truth in the LTPJ only (F(1, 16) = 5.6 p = 0.03, partial h 2 = 0.26); the LTPJ response during moral judgment was higher for true beliefs than false beliefs. No significant effects of condition were observed in any of the other ROIs.

4 Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the phenomenon of moral luck: why do we blame people for outcomes that aren’t under their control? For example, when Mitch leaves his son by the bathtub, telling him to stay put and reasonably believing that he will do so, why do we judge Mitch more morally blameworthy when his son climbs into the bath and drowns, than when his son stays put? Previous accounts of moral luck have attributed this asymmetry in our moral judgments to the asymmetry in outcomes (e.g., drowning versus no drowning), suggesting that bad outcomes lead to more moral blame (Baron and Hershey 1988; Nagel 1979; Williams 1982). These accounts have typically neglected an alternative possibility: unlucky agents are judged to be more morally blameworthy not just because of the bad outcomes they cause but because of their false beliefs. Traditional “moral luck” scenarios confounded false beliefs and bad outcomes, making it impossible to test for the contributions of truth (true vs. false beliefs) and outcome (neutral vs. bad) to moral luck asymmetries. To compare the contributions of false beliefs and bad outcomes to moral luck, we therefore introduced an “extra lucky” condition, in which the agent’s belief was false but the outcome was neutral (e.g., Mitch’s son climbs into the tub but ends up, luckily, fine).

As predicted, we found that false beliefs contribute more to moral luck than bad outcomes: the difference in moral blame for false versus true beliefs was greater than the difference in moral blame for bad versus neutral outcomes. Agents with false beliefs were judged to be more blameworthy than agents with true beliefs, even when no bad outcome occurred. For example, Mitch was blamed more when his belief was false (e.g., his son gets in the tub) than when his belief was true (e.g., his son stays put), even when no harm came to his son in either case. We also found that participants judged false beliefs to be less justified than the corresponding true beliefs, and that it was this difference in belief justification that drove the corresponding difference in moral blameworthiness. Moreover, it did not matter whether Mitch’s reason for his belief was good or bad—Mitch was blamed more for false beliefs than true beliefs regardless of his reason for his belief.

Our results could be interpreted as evidence for either a rational, or an irrational, mechanism of moral luck. In our data, judgments of belief justification accounted for much of the variance in judgments of moral blameworthiness. One strong, rational, and normatively appropriate determinant of judgments of belief justification was the stated reason for the agent’s belief. Predictably, and rationally, participants judged beliefs based on bad reasons to be less justified than beliefs based on good reasons, and beliefs based on unspecified reasons were of intermediate status. Consequently, agents with bad reasons for their beliefs were judged more morally blameworthy. In addition, though, judgments of belief justification were also influenced by the truth of the belief. This influence of truth on perceived justification is considered to be an irrational bias by some (Royzman and Kumar 2004) and normatively legitimate by others (Richards 1986; Rosebury 1995).

As we predicted, moral luck thus appears to depend primarily on judgments about the agent’s mental states. Importantly, however, we also observed an independent influence of bad outcomes on moral blame, which could not be explained by any influence on belief justification. As predicted by traditional non-rationalist accounts of moral luck, judgments of the agent’s moral blameworthiness were directly affected by whether outcomes were bad or neutral. We note also that our methods may have underestimated the role of outcomes on some moral judgments (Cushman 2008). In general, outcomes exert a greater influence on judgments of punishment (Cushman 2008; Rosebury 1995) than on judgments of moral blameworthiness (measured here) or moral wrongness.

Interestingly, we found that both moral judgments and belief justification judgments were influenced by bad outcomes particularly when agents had bad reasons for their beliefs. In other words, the same false beliefs based on the same bad reasons were judged to be significantly less justified when they led to bad outcomes than when they led to neutral outcomes; in the same contrast, the agents were also judged more blameworthy. This overall pattern in moral judgments and belief justification judgments suggests that outcomes make a bigger difference in the case of negligence and recklessness.

Given the parallel patterns for moral judgments and belief justification judgments, we also investigated whether the limited influence of outcome on moral judgments was due to the similarly limited influence of outcome on belief justification judgments (Baron and Hershey 1988; Royzman and Kumar 2004). Do participants judge agents causing bad outcomes to be more morally blameworthy because they first judge them to have less justified beliefs? We found little evidence for this claim. Instead, our results suggest that in the limited context where different outcomes translate to different moral judgments, the influence of outcomes is direct and leads to a subsequent difference in belief justification judgments. That is, in these cases, we observed an unexpected influence of moral judgments on mental state judgments.

One possible explanation for why we found moral judgments to influence mental state judgments is that participants initially make moral judgments based partially on outcomes, and then spontaneously seek to justify those judgments to themselves by appealing to differences along a dimension they rationally endorse: belief justification (Kliemann et al. 2008; Alicke 2000). This phenomenon may thus converge with other evidence showing that people appeal to rationally endorsed principles when dumbfounded by their own judgments made on other bases. For example, people sometimes insist that incest is wrong because it causes psychological harm to the participants or physical harm to the potential progeny, even when the scenario stipulates that no harm at all was caused. Haidt (2001) interprets these results as evidence that participants’ initial moral judgments are driven by an emotional reaction (disgust), which they do not endorse reflectively, and so participants appeal instead to a principle of harm, which they do endorse.

On this view, our results may be related to another phenomenon in which moral judgments influence mental state judgments: the Knobe effect or side-effect effect (for a review, see Knobe 2005; but see Guglielmo and Malle, in prep). When an agent causes a bad outcome, which he “doesn’t care about” (e.g., a CEO who implements a profitable policy that also happens to harm the environment), participants judge than the agent intentionally brought about the negative outcome. By contrast, when an agent causes a good or neutral outcome, which he “doesn’t care about” (e.g., a CEO who implements a profitable policy that also happens to help the environment) participants are less likely to say the agent intentionally brought about the positive or neutral outcome. Across many studies, participants judge the agent who caused the bad outcome to have acted more intentionally, to have intended the outcome more and to have desired the outcome more (Pettit and Knobe 2009). Recent work suggests that the Knobe effect may obtain even for epistemic states (e.g., knowledge; Beebe and Buckwalter 2010). For example, participants are more likely to agree that the CEO knew what would happen, when the environment was harmed versus helped. These effects may also relate more broadly to philosophical theories and recent psychological evidence suggesting that the context in which an agent believes or knows something may alter an observer’s assessment of that mental state. For example, observers are less confident that an agent knows the bank is open if the agent’s life depends on the bank’s being open (high stakes) than if the stakes are low (e.g., DeRose 1992; Stanley 2005; May et al. 2010).

The current study’s neural evidence is also consistent with this account. If bad outcomes lead to harsher moral judgments and then to greater consideration of agents’ beliefs, we should expect bad outcomes to be associated with enhanced activation of brain regions for belief reasoning, late in the trial. In two regions consistently associated with belief reasoning in moral and non-moral contexts, the RTPJ and the LTPJ (e.g., Young et al. 2007; Young and Saxe 2009a; Saxe and Kanwisher 2003), the response was significantly higher following bad outcomes versus neutral outcomes. The differential neural response appeared quite late in the stimulus, around the time of the moral judgment, rather than at the time that the belief was presented, prior to the judgment. Unlike subjects’ explicit judgments, though, in which outcomes mattered mostly when the agent had a bad reason for his or her beliefs, the neural response was higher for bad outcomes, regardless of the agent’s reasons. The average percent signal change in the RTPJ and LTPJ may reflect greater consideration of mental states for bad outcomes across all conditions.

The average percent signal change in the RTPJ and LTPJ, at the time of judgment, was not affected by basic features of the beliefs themselves: truth and justification. Instead, the response was equally high for true and false beliefs, and justified and unjustified beliefs. There are two possible interpretations of these results. First, these regions may represent the contents of beliefs, but not their truth or justification. Alternatively, these regions may contain information about belief truth and/or justification, which cannot be detected in the average percent signal change of the ROI (averaged across all supra-threshold voxels; Young and Saxe 2008, 2009b). If so, these features of attributed beliefs may be detectable in more fine-grained measures of brain activity, such as the pattern of response across voxels within a region.

In sum, in resisting moral luck and its paradoxical nature, we might take solace in several aspects of the present results. First, while bad outcomes do lead directly to more moral blame (independent of factors that affect belief justification), such outcome-based moral luck appears to be most pronounced in the case of negligent or reckless individuals who are already unjustified to think they won’t cause harm. Second, moral judgments do appear to be dominated by factors we reflectively endorse as morally relevant: whether agents have good or bad reasons for their beliefs, whether these beliefs are true or false. When assigning moral blame, we care mostly about whether agents are justified in thinking that they won’t cause harm. To the extent that moral luck asymmetries are driven by such mental state assessments, we may be able to defend a rational approach to morality.

References

Alicke, M.D. 2000. Culpable control and the psychology of blame. Psychological Bulletin 126: 556–574.

Baron, J., and J.C. Hershey. 1988. Outcome bias in decision evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 569–579.

Beebe, J., and W. Buckwalter. 2010. The epistemic side-effect effect. Mind and Language.

Ciaramidaro, A., M. Adenzato, I. Enrici, S. Erk, L. Pia, B.G. Bara, et al. 2007. The intentional network: How the brain reads varieties of intentions. Neuropsychologia 45(13): 3105–3113.

Cushman, F. 2008. Crime and punishment: Distinguishing the roles of causal and intentional analysis in moral judgment. Cognition 108: 353–380.

DeRose, K. 1992. Contextualism and knowledge attributions. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 52: 913–929.

Fletcher, P.C., F. Happe, U. Frith, S.C. Baker, R.J. Dolan, R.S.J. Frackowiak, and C.D. Frith. 1995. Other minds in the brain: A functional imaging study of “theory of mind” in story comprehension. Cognition 57: 109–128.

Gallagher, H.L., F. Happe, N. Brunswick, P.C. Fletcher, U. Frith, and C.D. Frith. 2000. Reading the mind in cartoons and stories: An fMRI study of ‘theory of mind’ in verbal and nonverbal tasks. Neuropsychologia 38: 11–21.

Gobbini, M.I., A.C. Koralek, R.E. Bryan, K.J. Montgomery, and J.V. Haxby. 2007. Two takes on the social brain: A comparison of theory of mind tasks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 19(11): 1803–1814.

Greene, J.D., R.B. Sommerville, L.E. Nystrom, J.M. Darley, and J.D. Cohen. 2001. An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science 293: 2105–2108.

Greene, J.D., L.E. Nystrom, A.D. Engell, J.M. Darley, and J.D. Cohen. 2004. The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron 44(2): 389–400.

Guglielmo, S., and B. Malle. (in prep). Can unintended side effects be intentional? Solving a puzzle in people’s judgments of intentionality and morality.

Haidt, J. 2001. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review 108: 814–834.

Kliemann, D., L. Young, J. Scholz, and R. Saxe. 2008. The influence of prior record on moral judgment. Neuropsychologia 46: 2949–2957.

Knobe, J. 2005. Theory of mind and moral cognition: Exploring the connections. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9: 357–359.

May, J., W. Sinnott-Armstrong, J. Hull, and A. Zimmerman. 2010. Practical interests, relevant alternatives, and knowledge attributions: An empirical study. Review of Philosophy and Psychology.

Nagel, T. 1979. “Moral luck”. Mortal questions, 24–38. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olson, K., M. Banaji, C. Dweck, and E. Spelke. 2006. Children’s biased evaluations of lucky versus unlucky people and their social groups. Psychological Science 17: 845–846.

Olson, K., Y. Dunham, C. Dweck, E. Spelke, and M. Banaji. 2008. Judgments of the lucky across development and culture. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94: 757–776.

Pettit, D., and J. Knobe. 2009. The pervasive impact of moral judgment. Mind and Language 24(5): 586–604.

Poldrack, R. 2006. Can cognitive processes be inferred from neuroimaging data? Trends in Cognitive Sciences 10: 59–63.

Richards, N. 1986. Luck and desert. Mind 65: 198–209. page reference is to the reprint in Statman 1993b.

Rosebury, B. 1995. Moral responsibility and moral luck. Philosophical Review 104: 499–524.

Royzman, E., and R. Kumar. 2004. Is consequential luck morally inconsequential? Empirical psychology and the reassessment of moral luck. Ratio 17: 329–344.

Ruby, P., and J. Decety. 2003. What you belief versus what you think they believe: A neuroimaging study of conceptual perspective-taking. European Journal of Neuroscience 17: 2475–2480.

Saxe, R., and N. Kanwisher. 2003. People thinking about thinking people. The role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind”. Neuroimage 19(4): 1835–1842.

Stanley, J. 2005. Knowledge and practical interests. Oxford: Clarendon.

Vogeley, K., P. Bussfield, A. Newen, S. Herrmann, F. Happe, P. Falkai, et al. 2001. Mind reading: Neural mechanisms of theory of mind and self-perspective. Neuroimage 14: 170–181.

Williams, B. 1982. “Moral luck.” Moral luck, 20–39. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Young, L., and R. Saxe. 2008. The neural basis of belief encoding and integration in moral judgment. NeuroImage 40: 1912–1920.

Young, L., and R. Saxe. 2009a. Innocent intentions: A correlation between forgiveness for accidental harm and neural activity. Neuropsychologia 47: 2065–2071.

Young, L., and R. Saxe. 2009b. An fMRI investigation of spontaneous mental state inference for moral judgment. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 21: 1396–1405.

Young, L., F. Cushman, M. Hauser, and R. Saxe. 2007. The neural basis of the interaction between theory of mind and moral judgment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(20): 8235–8240.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging. Many thanks to Josh Knobe and Fiery Cushman for their helpful feedback on this manuscript, and to Noel Morales and Jon Scholz for their help in data collection.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Young, L., Nichols, S. & Saxe, R. Investigating the Neural and Cognitive Basis of Moral Luck: It’s Not What You Do but What You Know. Rev.Phil.Psych. 1, 333–349 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-010-0027-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-010-0027-y