Abstract

Young children often struggle with referential communications because they fail to compare all valid referents. In two studies, we investigated this comparison process. In Study 1, 4–7 year-olds (N = 114) were asked to categorize pairs of objects according to their similarities or differences, and then identified a unique quality of one of the objects by responding to a referential question. Children found it easier to judge the differences between objects than similarities. Correct judgments of differences predicted accurate identifications. In Study 2, 4–5 year-olds (N = 36) again categorized according to similarities or differences, but this time were asked for verbal explanations of their decisions. Recognition of differences was easier than recognition of similarities. Explanations of errors were either: (a) ambiguous; (b) color error: (c) thematic (creative imaginative explanations). Children offered thematic explanations when they failed to recognize similarities between objects, but not for errors of difference.

Résumé

Les jeunes enfants ont souvent du mal avec les communications référentielles parce qu'ils ne parviennent pas à comparer tous les référents valides. Dans deux études, nous avons étudié ce processus de comparaison. Dans l'étude 1, des enfants de 4 à 7 ans (N = 114) ont été invités à catégoriser des paires d'objets en fonction de leurs similitudes ou différences, puis ont identifié une qualité unique de l'un des objets en répondant à une question référentielle. Les enfants ont trouvé plus facile de juger les différences entre les objets que les similitudes. Des jugements corrects des différences prédisaient des identifications précises. Dans l'étude 2, les enfants de 4 à 5 ans (N = 36) ont à nouveau été classés en fonction des similitudes ou des différences, mais cette fois-ci, on leur a demandé des explications verbales de leurs décisions. La reconnaissance des différences était plus facile que la reconnaissance des similitudes. Les explications des erreurs étaient soit: a) ambiguës; b) erreur de couleur; c) thématique (explications imaginatives créatives). Les enfants ont proposé des explications thématiques lorsqu'ils n'ont pas réussi à reconnaître les similitudes entre les objets, mais pas pour les erreurs de différence.

Resumen

Los niños pequeños a menudo tienen dificultades con las comunicaciones referenciales porque no pueden comparar todos los referentes válidos. En dos estudios, investigamos este proceso de comparación. En el Estudio 1, se pidió a niños de 4 a 7 años (N = 114) que categorizaran pares de objetos de acuerdo con sus similitudes o diferencias, y luego identificó una cualidad única de uno de los objetos respondiendo a una pregunta referencial. A los niños les resultó más fácil juzgar las diferencias entre objetos que las similitudes. Los juicios correctos de las diferencias predijeron identificaciones precisas. En el Estudio 2, niños de 4 a 5 años (N = 36) nuevamente categorizados según similitudes o diferencias, pero esta vez se les pidió explicaciones verbales de sus decisiones. El reconocimiento de las diferencias fue más fácil que el reconocimiento de las similitudes. Las explicaciones de los errores fueron: (a) ambiguas; (b) error de color; (c) temática (explicaciones creativas, imaginativas). Los niños ofrecieron explicaciones temáticas cuando no reconocieron similitudes entre objetos, pero no precursores de la diferencia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When we ask young children questions, we have expectations about what constitutes an appropriate response. This is particularly so when the question requires children to identify something: for example, when we ask them about their favorite toy, or what color pencil they want, or even “which” object they are referring to (Basco et al., 2021). For children to be able to respond successfully to such requests they must employ referential communication skills: comparing all the valid referents and replying appropriately with information that identifies the target (e.g., Asher & Wigfield, 1981). In the current research, we investigated these comparison and communication processes in young children’s responses to referential questions about different object types.

In English, referential questions tend to make use of words such as “which” or “what” and, as in the examples given above, tend to refer to objects or their attributes, and require a specific response (Kearsley, 1976; Robinson & Rackstraw, 1972). Referential questions are among the earliest that young children employ (following closely after “why” and “how” questions), and by around 4 years of age are in frequent use (Searle, 1969). However, the development and understanding of children’s responses to these types of questions is less clear.

On the surface, one would expect young children to know how to respond to referential questions. Three-year-olds are good at learning the names of objects (Birch & Bloom, 2002), understand that “one” refers to a single object (e.g., Condry & Spelke, 2008; Wynn, 1992), and by 5 years of age, young children can answer questions appropriately (if the questions are logical and make sense) (Waterman, et al., 2000). Consequently, they should be able to grasp the meaning of a typical referential question that requires them to identify a desired object. For example, when asked “which one do you want?” a child must reply with enough information to communicate the identity of their chosen object. However, young children’s understanding of communication must not be overestimated (Siegal, 1997): they can have problems understanding how objects can be uniquely represented (e.g., Apperly & Robinson, 1998), can have difficulty communicating the identity of an intended referent to others (e.g., Asher & Oden, 1976), and can struggle to produce a narrative communication unless a referent is present (Carmiol et al., 2018).

Most of the referential communication tasks used in existing research (e.g., Krauss & Glucksburg, 1969; Lloyd et al., 1995; Roby & Kidd, 2008; Uzundag & Küntay, 2018) include two test phases: first, a speaker generates an informative description so that a listener can understand which one of a selection of objects is being referred to. In the second phase, a listener decides if they can identify an object following an unambiguous verbal description by a speaker, or whether they must ask the speaker for more information after an ambiguous message. The purpose of these two test phases is to assess the effectiveness of verbal communications; both generated and received (Roberts & Patterson, 1983; Roby & Kidd, 2008), to assess the development of these abilities (Lloyd et al., 1998), or to assess whether informative descriptions can be improved (Uzundag & Küntay, 2018).

To understand the development of an ability in childhood we often start by considering how adults behave in a comparable situation. So, how do adults successfully generate an informative description and indicate a referent to other people? Research suggests that a speaker must supply enough information (to distinguish between all referents) for a listener to understand which object they might be referring to (e.g., Rosenberg & Cohen, 1966). It follows that the speaker must have two abilities; first, they must be able to compare all the valid referents and understand how they are unique and different, and second, they must be able to communicate that knowledge successfully to others. An effective communication therefore appears to rely on differences being identified and a successful comparison being carried out. Comparing objects involves deep processing: it highlights any differences (and similarities) between objects that may not be apparent when those objects are examined individually (e.g., Graham et al., 2010).

One explanation of why young children can have difficulty with referential communications is that they are less likely to carry out a comparison between all referents (Asher, 1976; Asher & Parke, 1975; Asher & Wigfield, 1981; Bearison & Levey, 1977; Camaioni & Ercolani, 1988). They tend to focus on the target object, ignore or disregard other possibilities, and fail to identify the differences (Asher & Oden, 1976; Girbau & Boada, 1996). Therefore, they cannot generate an adequate description to indicate the intended object, and the referential communication fails (Glucksberg et al., 1975). However, while such research concerns referential communication, it has tended to focus on children’s ability to generate informative messages, rather than their response to referential questions.

Other research has linked comparison processing to successful referential communication in children (Camaioni & Ercolani, 1988). Five to 8-year-olds were shown eight or nine drawn images and had to match a target (presented visually or described verbally) to one of the stimuli. They then had to generate effective verbal descriptions of objects so that someone else could identify them. Performance on the comparison tasks were highly predictive of children’s communication abilities (Camaioni & Ercolani, 1988). Children who could successfully compare objects, were then able to identify what information they should to pass on to others. Children who failed to communicate effectively in this study did so because they were unable to distinguish what made the target different from those around it. It is not clear why children failed to recognize these differences, or whether it impacts on children’s ability to answer referential questions.

The current research aimed to clarify why young children sometimes fail to recognize what differentiates one object from others around it, and to establish whether the focus on “differences” is necessary for children to answer referential questions. To do this, we had to get children to demonstrate their understanding of how objects might be similar, and how they might be different, as well as answer a referential question about an object. Therefore, in Study 1, children were presented with pairs of objects and demonstrated their comparison abilities by categorizing the objects according to their similarities or differences. Children then demonstrated their ability to communicate the identity of one of each pair of objects by responding to a referential question. In Study 2, we focussed on children who made errors in categorizing objects by similarity and difference and asked then to explain their decisions.

Study 1

Method

Participants

One hundred and fourteen children participated from a primary school serving a working-class population in the UK. There were 35 four-year-olds (Mean = 4 years and 4 months (4;4), range 3;10–4;9), 28 five-year-olds (M = 5;2, range 4;10–5;8), 29 six-year-olds (M = 6;2, range 5;9–6;8), and 22 seven-year-olds (M = 7;3, range 6;9–7;10). Half of each age group were female. Children belonged to following ethnic groups: white British (85); Asian (26); black African (1), and other (8). Teachers described all the children who took part as having a good understanding of English.

Materials

The materials consisted of four pairs of “target” objects, 20 “grouping” objects, an opaque bag, plastic containers, two plates, and a teddy. The four pairs of target objects were: a toy sheep and toy pig; a toy car and a toy train; a small red ball and a small blue ball; a small yellow block and a small green block. The opaque bag contained the target objects when they were not in use. The grouping objects consisted of toy farm animals; toy vehicles; colored balls; colored clocks (five of each). The plastic containers held the grouping objects when they were not in use. The plates were used to display the grouping objects while they were being used in the study. The teddy acted as a recipient for a target object in the communication task.

Design

The study used a mixed 4(age: 4 years vs. 5 years vs. 6 years vs. 7 years) × 2(comparison task: similarity vs. difference) design with repeated measures on the last factor. Responses to the communication part of the task were recorded. The experiment consisted of four separate trials. In Trial 1 children were presented with two diverse kinds of toy animals; Trial 2 was two distinct kinds of toy vehicles; Trial 3 was two different colored blocks; and Trial 4 was two different colored balls).

Each trial consisted of grouping the pair of objects by similarity and by difference, and a communication task that involved identifying the target object of the pair (see Table 1). The identification task always followed the comparison task, regardless of their ordering (since in referential communication tasks the comparison of possibilities must come before identification). We counterbalanced trials to avoid order effects.

Procedure

The researcher tested children individually while sat at a table in a quiet part of the school. For each trial there was a familiarisation task, followed by a comparison task, followed by an identification task.

Familiarisation task. We felt it was important to be explicit about the similarities and differences between objects, so that the children (especially the younger ones) were clear about these factors. At the beginning of each of the four trials, the researcher gave children a pair of toys (the target objects) that were different in one way, and similar in another. Children were encouraged to look at and pick up the toys while the researcher stated how they differed, and how they were similar (order counterbalanced).

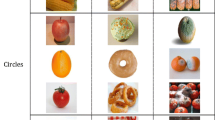

Comparison task: The purpose of this task was to check children’s recognition of how each pair of objects was similar and how they differed. After each familiarisation part of the trial, the researcher carried out a similarity sub-task and a difference sub-task (order counterbalanced). For each sub-task, the researcher placed ten additional toys on two plates on the table (this kept each grouping distinct and stopped toys moving around on the table). The researcher stated that all the toys on each plate “belonged together” and asked the children to put their toy toys “where you think they belong.” The researcher told children that the two toys might go together in one group (i.e., they could both be put on one plate) or they might go in separate groups (i.e., one could be put on each plate). The researcher noted on a record sheet children’s placement of the two toys. The experimenter then returned the two toys to the children and removed the grouping objects from the plates. The other sub-task followed the same procedure. Once both the comparison tasks were completed, the researcher removed all the additional objects and plates, leaving the children with the initial two toys.

Identification task: The purpose of this task was to check children’s ability to recognize the identifying information about an object. Following the comparison task in each trial, the researcher placed the teddy on the table and advised the child that Teddy has just arrived to play and that they should, “give Teddy one of your toys.” The researcher then asked the test question, “Which one have you given Teddy?” Children responded and their answers were recorded as either correct (identifying information given) or incorrect (no identifying information given).

At the end of the identification task, the researcher placed the two objects in the opaque bag and the next trial began until all four trials were complete. At the end of the trials, the experimenter gave children a sticker and returned them to their classroom.

Results

Coding

For the comparison task, children received a score of 1 for each correct placement of a target object in the similarity sub-task and a score of zero for each placement that was incorrect. They also received a score of 1 for each correct placement in a difference sub-task, and a score of zero if it was incorrect. Children could receive a maximum score of 4 for similarity judgements, and a maximum score of 4 for judgements of differences. For the identification task, children received a score of 1 if they correctly communicated the aspect of the object that uniquely identified it from the other object in the pair and a score of zero if they stated some attribute which did not uniquely identify the object or if they failed to give any identifying information. For example, if a child gave Teddy one of two different colored balls, they were deemed correct if responded to the test question, “Which one have you given Teddy?” by answering, “the red one” and deemed incorrect if they said, “the ball.” Children could receive a maximum score of 4 for the identification task. The means of all scores are displayed in Table 1.

Analyses

In line with previous similar studies that gave children repeated trials we used parametric analyses to evaluate the data (e.g., Camaioni & Ercolani, 1988). Initially, a mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out between age (4 years vs. 5 years vs. 6 years vs. 7 years) and comparison task (similarity vs. difference) with repeated measures on the latter. As expected, there was a significant main effect of age (F(3, 110) = 4.67, p = 0.004, η2p = 0.11), with pairwise comparisons showing that 7-year-olds performed significantly better than 4-year-olds (p = 0.021). There was also a significant main effect of comparison task, (F(1, 110) = 15.46, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.12), with recognition of differences (M = 3.83, SD = 0.48) significantly higher than recognition of similarities (M = 3.41, SD = 1.09). There was no significant interaction between age and comparison task.

We then wanted to establish whether there was a significant difference between the age of children correctly answering the identity question A one-way independent ANOVA was carried out with the independent variable of age (four levels: 4 years versus 5 years versus 6 years versus 7 years) and the dependent variable of correct responses. The results showed no significant difference between the different age groups (p = 0.08) (see Table 1 for means).

Next, a multiple regression analysis was carried out to determine what would best predict successful communication of the identity of an object. Age, similarity judgements, and difference judgements were the predictor variable, whilst the identity scores were the outcome variable. Correlations suggested that the age of children was positively and weakly associated with recognition of differences, r(112) = 0.31, p < 0.001, recognition of similarities r(112) = 0.24, p = 0.006, and correct identification, r(112) = 0.19, p = 0.021. Judgement of difference were also positively but weakly associated, and with correct identification, r(112) = 0.28, p = 0.001, with judgements of similarity, r(112) = 0.21, p = 0.014. There was no significant correlation between judgement of similarity and correct identification.

The relationship between the predictor variables and the outcome variable was weak (R = 0.31). The results of the regression indicated that the three predictors explained only 9.3% (adjusted R2 = 0.68) of the variance (F(3, 110) = 3.76, p = 0.013) (see Table 2). It was found that correct judgement of the differences between pairs of objects significant predicted correct identification (β = 0.45; t = 2.61, p = 0.010; 95% Cl 0.059–0.43). Neither judgements of similarities nor age of child predicted identification (lowest p = 0.20).

Study 1

Discussion

The aim of Study 1 was to clarify the comparison process in 4–7-year-old’s ability to answer referential questions. Additionally, we sought to investigate the recognition of similarities and differences during the comparison process and clarify which predicted children’s ability to recognize identifying information and answer referential questions.

All the 5–7-year-olds (bar one) and most 4-year-olds answered the referential question correctly. As expected, older children found the similarity and difference tasks easier than younger children, indeed 7-year-olds performed with few errors and much better than one would expect at standard comparison or referential communication tasks (e.g., Lloyd et al., 1998). Our comparison task required the objects to be distinctly categorized by their similarities and differences, unlike previous comparison tasks (e.g., Lloyd et al., 1995). However, we had pointed out the similarities and differences to children, as part of the familiarisation procedure, so it is likely that this helped the older children to recognize the prominent features of the objects.

Nevertheless, children found it harder to recognize the similarities between pairs of the objects than recognize the differences. While it is only strictly necessary to recognize the differences between objects when looking for a unique identifier, we wondered why children were not as proficient at recognizing similarities. Even 7-year-olds, who had no difficulty with the other tasks, occasionally faltered with the similarity task. The aim of Study 2 was to investigate this further by asking children to verbalize or explain their reasons for “grouping” objects as they did.

Study 2

Method

Participants

Thirty-six children (21 girls) participated from a primary school serving a working-class population in the UK (a different school to Study 1). There were 18 four-year-olds (M = 4; 9), range 4; 3–5; 2), and 18 five-year-olds (M = 5; 8, range 5;4–6; 1) (we kept to a younger cohort due to the near ceiling performance of 6- and 7-year-olds children in Study 1). Children belonged to following ethnic groups: white British (34), black Caribbean (1), and other (1). Teachers described all the children who took part as having a good understanding of English.

Materials

We used the materials from Study 1 (except Teddy, as no identity/communication task was included). A digital voice recorder documented children’s verbal response to the explanation question.

Procedure

The familiarization procedure followed the same format as Study 1. There was no identity task. The comparison task was as used in Study 1, apart from one adjustment: When children had grouped each object (either for similarity or difference) they were asked why they had put the objects in those places. For example, children were asked, “Can you put your two toys where you think they belong” followed by “Why do they belong there?” or “Why does that belong there?”.

Design

The study used a mixed 2(age: 4 years vs. 5 years) × 2(comparison task: similarity vs. difference) design with repeated measures on the last factor. Each child received four trials. The independent variables were age and comparison task. The dependent variables were the children’s responses to the comparison tests (if they grouped the objects correctly according to similarity and difference). We also asked children’s explanations of their choices and noted their responses. We counterbalanced the ordering of the trials and the comparison tasks, to avoid order effects.

Results

Coding

As in Study 1, children received a score of 1 if they placed objects in the appropriate groupings for each of the similarity and difference tasks, and a score of 0 if they were incorrect. This meant that children could potentially gain a maximum score of four for each of the tasks.

Analyses

We carried out a 2(age: 4 years vs. 5 years) × 2(comparison task: similarity vs. difference) mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures on the last factor. We found a main effect of comparison task, F(1, 34) = 5.36, p = 0.027, η2p = 0.14, where judgements of difference (M = 3.78, SD = 0.089) were significantly better than judgements of similarity (M = 3.31, SD = 0.18) (see Table 3). There was no effect of age and no interaction.

As we had found no difference between the two age groups, we collapsed the data across these factors to examine the overall number of errors made. There were 9 errors made in the difference task and 26 errors made in the similarity task. We then examined the type of explanations children offered. Children’s error explanations fell under three broad topic areas, (a) ambiguous (i.e., they did not offer a justification, or their response was vague) (b) color error (i.e., their explanation was related to an incorrect color matching of objects), and (c) thematic explanations (i.e., they suggested an alternative relationship or story involving the objects) (see Table 4 for examples). Of the error explanations in the difference task, 4 (45%) related to color, 5 (55%) were ambiguous, and none were thematic. In the similarity task, however, 17 (65%) error explanations related to color, 9 (35%) related to thematic explanations, and none were ambiguous.

Study 2

Discussion

There were more errors with the similarity task than the difference task. Children’s explanations of their errors were classified as either a) ambiguous, b) color, or c) thematic. Ambiguous errors may have been due to difficulties in verbalizing the reasoning process. Color errors could have been due to the focus on perceptual similarity that young children tend to have in categorization activities (Namy & Clepper, 2010). Or a “preference” for color might be dominant to the extent that it overrides or interferes with other types of categorizations (Catherwood et al., 1989).

Interestingly, the thematic explanations only occurred when toy animals or vehicles were used, and not the balls and blocks. Toy animals can trigger the activation of mental representations of experiences of real-life animals (Ware et al., 2006) so it seems likely that toy vehicles could activate mental representation of experiences of real-life vehicles. These mental representations could have become dominant in children’s thoughts and overshadowed the required judgements of similarity. Or, children may have made more qualitative judgements of the features of the objects, rather than focusing on general similarity (Diesendruck et al., 2003; Hammer & Diesendruck, 2005; Medin et al., 1993) and this led to more unorthodox categorizations.

Another possibility is that children who created thematic explanations to justify their (incorrect) categorizations, simply had better skills in communication and creativity: they were able to invent a scenario to explain their choice and verbalise it. However, this seems improbable: whilst the creation of a “narrative” is one of the more complex types of generative communication (Carmiol et al., 2018), the capacity to talk about imaginative thoughts predicts Theory of Mind (ToM) ability in young children (Peterson & Slaughter, 2006). ToM, the ability to understand someone else’s mental states (Wellman, 2017). is linked to more advanced abilities in many fields, so while children with higher levels of ToM could certainly be more creative and communicative, it seems less likely that they would be making such errors of categorization in the first instance. Nevertheless, this may be an interesting route for further investigation.

General Discussion

The aim of the current research was to clarify whether children compared the similarities and differences between pairs of objects before they successfully answered referential questions about those objects. In Study 1, we found that children who were able to correctly categorise objects according to their differences also seemed to be able to answer the referential question about one of those objects. However, there was no link between categorizing according to similarity and answering the same question. Other studies have found that children of this age can demonstrate how pairs of objects differ but struggle to respond to questions referring to that difference (Waters & Beck, 2012). Our findings suggested that it was only necessary for children to recognize how the pairs of objects differed, for them to be able to communicate the identity of the chosen referent.

In Study 2, we confirmed our previous findings that children found it easier to categorise pairs of objects according to differences, than to similarities. Interestingly, children’s verbal explanations of their errors, when categorizing objects, fell under three broad topic areas, (a) ambiguous, (b) color error, and (c) thematic explanations. Children’s errors were mostly related to the color of the objects in questions: children ignored obvious similarities and differences and instead focused on the color of the objects to try to explain their categorization errors (though often their color explanations were also incorrect). The next most frequent error seemed to be based on a qualitative, experiential factor: children created a mini story or narrative to explain their incorrect categorization of objects.

In both our studies, children found it harder to categorise pairs of objects according to their similarities, than to categorise according to differences. In one sense, this was to be expected, as one only needs to recognize differences between objects to be able to identify unique referents. Nevertheless, the recognition of commonalities (or similarities) between objects, is thought to be the most important stage of the comparison process for children (Gentner & Namy, 1999, 2006; Hammer et al., 2009), especially when the objects have been clearly labelled (as in our case) (Namy & Gentner, 2002). Yet, we found no inflated preference for seeking similarities, as suggested by previous research (e.g., Hammer et al., 2009). One possibility is that when children need to answer a referential question in a more naturalistic environment (such as our studies where they chose, manipulated, and named toys); recognizing the differences between things is simply sufficient. Or it might be that only children with more advanced cognitive functioning can attend to both similarities and differences between objects (Basco & Nilsen, 2017). There is also the chance that without the support and confirmation of another person’s facial cues, children ignore similarities between referents (Basco et al., 2021). Further research may be needed to clarify why preference for seeking similarities is not always found.

In conclusion, comparison processing is important for communicating about unique referents: it highlights any similarities and differences between objects that may not be apparent when those objects are examined individually (Graham et al., 2010). The results of the current research showed that children who successfully compared objects, by recognizing how different they were, went on to answer correctly referential questions about those objects. Young children’s understanding of how they can gain certain aspects of knowledge can also depend upon successful recognition of differences (Waters & Beck, 2012, 2015). In addition, children’s success at referential communication is linked to higher perspective taking abilities (Roberts & Patterson, 1983), and higher ToM levels (Resches & Pérez Pereira, 2007). Our findings offer support for the link between recognizing the subtleties of how objects differ, and many other cognitive abilities that develop throughout young childhood. Nonetheless, there is still uncertainty about the link between the creation of elaborate narratives, higher ToM abilities, and better categorization abilities. Further investigation is clearly needed to help determine the complexities of young children’s understanding of identification of unique referents, and the role of comparison in developing responses to referential questions.

References

Apperly, I. A., & Robinson, E. J. (1998). Children’s mental representations of referential relations. Cognition, 67, 287–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(98)00030-4

Asher, S. R. (1976). Children’s ability to appraise their own and another person’s communication performance. Developmental Psychology, 12(1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.12.1.24

Asher, S. R., & Oden, S. L. (1976). Children’s failure to communicate: Assessment of comparison and egocentrism explanations. Developmental Psychology, 12(2), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.12.2.132

Asher, S. R., & Parke, R. D. (1975). Influence of sampling and comparison processes on development of communication effectiveness. Journal of Educational Psychology, 67(1), 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0078672

Asher, S. R., & Wigfield, A. (1981). Influence of comparison training on children’s referential communication. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73(2), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.73.2.232

Basco, S. A., & Nilsen, E. S. (2017). What’s that you’re saying? Children with better executive functioning produce and repair communication more effectively. Journal of Cognition and Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2017.1336438

Basco, S. A., Nilsen, E. S., & Silva, J. (2021). How to turn that frown upside down: Children make use of a listener’s facial cues to detect and (attempt to) repair miscommunication. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 207, 105097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2021.105097

Bearison, D. J., & Levey, L. M. (1977). Children’s comprehension of referential communication: Decoding ambiguous messages. Child Development, 48(2), 716–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X01020001004

Birch, S. A. J., & Bloom, P. (2002). Preschoolers are sensitive to the speaker’s knowledge when learning proper names. Child Development, 73(2), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00416

Camaioni, L., & Ercolani, A. P. (1988). The role of comparison activity in the development of referential communication. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 11(4), 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/016502548801100401

Carmiol, A. M., Matthews, D. M., & Rodriguez-Villagra, O. A. (2018). How children learn to produce appropriate referring expressions in narratives: The role of clarification requests and modeling. Journal of CHild Language, 45(3), 736–752. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000917000381

Catherwood, D., Crassini, B., & Freiberg, K. (1989). Infant response to stimuli of similar hue and dissimilar shape - tracing the origins of the categorization of objects by Hue. Child Development, 60(3), 752–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb02755.x

Condry, K. F., & Spelke, E. S. (2008). The development of language and abstract concepts: The case of natural number. Journal of Experimental Psychology General, 137(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.137.1.22

Diesendruck, G., Hammer, R., & Catz, O. (2003). Mapping the similarity space of children and adults’ artifact categories. Cognitive Development, 18(2), 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2014(03)00021-2

Gentner, D., & Namy, L. L. (1999). Comparison in the development of categories. Cognitive Development, 14(4), 487–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2014(99)00016-7

Gentner, D., & Namy, L. L. (2006). Analogical processes in language learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(6), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00456.x

Girbau, D., & Boada, H. (1996). Private meaning and comparison process in children’s referential communication. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 25(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01726998

Glucksberg, S., Krauss, R. M., & Higgins, E. T. (1975). The Development of Referential Communication Skills. In F. D. Horowitz (Ed.), Review of Child Development. University of Chicago Press.

Graham, S. A., Namy, L. L., Gentner, D., & Meagher, K. (2010). The role of comparison in Preschoolers’ novel object categorization. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 107(3), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2010.04.017

Hammer, R., & Diesendruck, G. (2005). The role of dimensional distinctiveness in children’s and adults’ artifact categorization. Psychological Science, 16(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00794.x

Hammer, R., Diesendruck, G., Weinshall, D., & Hochstein, S. (2009). The development of category learning strategies: what makes the difference?. Cognition, 112(1), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2009.03.012

Kearsley, G. P. (1976). Questions and question asking in verbal discourse: cross-disciplinary review. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 5(4), 355–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01079934

Krauss, R. M., & Glucksburg, S. (1969). The development of communication: Competence as a function of age. Child Development, 40, 255–266. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127172

Lloyd, P., Camaioni, L., & Ercolani, P. (1995). Assessing referential communication skills in the primary school years: a comparative study. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.1995.tb00661.x

Lloyd, P., Mann, S., & Peers, I. (1998). The growth of speaker and listener skills from five to eleven years. First Language, 18(52), 81–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/014272379801805203

Medin, D. L., Goldstone, R. L., & Gentner, D. (1993). Respects for similarity. Psychological Review, 100(2), 254–278. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.2.254

Namy, L. L., & Clepper, L. E. (2010). The differing roles of comparison and contrast in children’s categorization. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 107(3), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2010.05.013

Namy, L. L., & Gentner, D. (2002). Making a silk purse out of two sow’s ears: Young children’s use of comparison in category learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 131(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1037//0096-3445.131.1.5

Peterson, C. C., & Slaughter, V. P. (2006). Telling the story of theory of mind: deaf and hearing children’s narratives and mental state understanding. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24(1), 151–179. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151005X60022

Resches, M., & Perez Pereira, M. (2007). Referential communication abilities and theory of mind development in preschool children. Journal of Child Language, 34(1), 21–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000906007641

Roberts, R. J., Jr., & Patterson, C. J. (1983). Perspective taking and referential communication: The question of correspondence reconsidered. Child Development, 54(4), 1005–1014. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129904

Robinson, W. P., & Rackstraw, S. J. (1972). A question of answers. Routledge and Kegan Paul PLC.

Roby, A. C., & Kidd, E. (2008). The referential communication skills of children with imaginary companions. Developmental Science, 11(4), 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00699.x

Rosenberg, S., & Cohen, B. (1966). Referential processes of speakers and listeners. Psychological Review, 73, 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023294

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge University Press.

Siegal, M. (1997). Knowing children: Experiments in conversation and cognition (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

Uzundag, B. A., & Küntay, A. C. (2018). Children’s referential communication skills: The role of cognitive abilities and adult models of speech. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 172, 73–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2018.02.009

Ware, E. A., Uttal, D. H., Wetter, E. K., & DeLoache, J. S. (2006). Young children make scale errors when playing with dolls. Developmental Science, 9(1), 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00461.x

Waterman, A. H., Blades, M., & Spencer, C. (2000). Do children try to answer nonsensical questions? British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18, 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151000165652

Waters, G. M., & Beck, S. R. (2012). How should we question young children’s understanding of aspectuality? British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 30(3), 376–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02044.x

Waters, G. M., & Beck, S. R. (2015). Verbal information Hinders young children’s ability to gain modality specific knowledge. Infant and Child Development, 24(5), 538–548. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1901

Wellman, H. M. (2017). The development of theory of mind: Historical reflections. Child Development Perspectives, 11(3), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12236

Wynn, K. (1992). Children’s acquisition of the number words and the counting system. Cognitive Psychology, 24(2), 220–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(92)90008-P

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Nuffield Foundation. The authors thank St Joseph’s Cathlolic Primary School (Keighley), Parkland Primary School, and Ramesah Qayyum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Waters, G.M., Dunning, P.L., Kapsokavadi, M.M. et al. Do Young Children Consider Similarities or Differences When Responding to Referential Questions?. IJEC 54, 321–337 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-021-00307-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-021-00307-6