Abstract

The importance of professional learning and development for quality in kindergartens has been established in international research. The fact that the kindergarten is a learning organization can be crucial in achieving necessary professional learning. The aim of this study was to investigate what characterizes Norwegian kindergartens as learning organizations. Our research question is: What kind of understanding do kindergarten managers have of a learning organization, what do they believe that a kindergarten must learn about and what do they perceive as characteristics of a learning kindergarten? We have conducted qualitative interviews with five kindergarten managers. The findings point to joint reflection as a key characteristic of a learning kindergarten. However, kindergartens struggle to make reflection a natural part of a day-to-day practice. Consequently, kindergartens fail to utilize an important potential for professional learning. Hence, we conclude that there is an untapped potential for professional learning and development in Norwegian kindergartens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

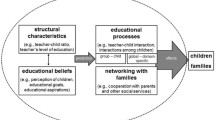

International research has shown the importance of kindergarten teachers’ competence and professional development for the quality of the early childhood education and care environment (Gotvassli, 2020; Manning et al., 2017; Saracho & Spodek, 2006). This means that professional learning and development among the kindergarten’s teachers is important to increase the quality of kindergartens. Quality of kindergartens is particularly related to the quality of relationships between teacher and children, which is considered the most important aspect for children’s well-being, development and learning (Gotvassli, 2020).

The need for professional development among kindergarten teachers is more important than ever. Kindergarten has an important function related to children's development, learning and education. In addition, kindergarten shall prepare children for school and participation in society. Professional development is important to ensure good professional practice and for kindergarten teachers to be able to meet changes in society and the needs of users.

Professional learning and development in the kindergarten sector can include various types of courses and training, coaching or mentoring, reflective techniques as well as the fostering of learning communities (Waters et al., 2018). We argue that to achieve necessary professional learning and development among kindergarten teachers the kindergarten must be a learning organization. The fact that the kindergarten is a learning organization will help ensure a continuous and practice-oriented competence development among the teachers and ensure that they are able to absorb and apply new knowledge and adapt to changes in society.

In Norway, it has since 2006 been stated in a numerous of policy documents that a kindergarten should be a learning organization (Skjæveland, 2019). The government’s goal is to develop high-quality kindergarten services for all children. This requires continuous competence development among kindergarten teachers. Thus, the kindergarten must be a learning organization (Ministry of Educations and Research, 2017). However, it has been pointed out that the concept of a learning organization is not explained or elaborated in the policy documents (Gotvassli, 2019a). The aim of our study is to give insight into kindergarten managers’ understanding of a learning organization and what characterizes kindergartens as learning organizations and thus contribute to our understanding of professional learning and development in kindergartens.

Kindergarten managers have overall responsibility for implementing the intention that the kindergarten should be a learning organization (Ministry of Education and Research 2013a). We can therefore expect that managers have some thoughts about kindergartens as learning organizations. Consequently, this article addresses the following problem: What characterizes a kindergarten as a learning organization according to kindergarten managers? To address this problem, we ask the following research questions: What kind of understanding do kindergarten managers have of a learning organization, what do they believe the kindergarten must learn about and what do they perceive as characteristics of a learning kindergarten? The answers to these questions will give us an increased opportunity to understand and discuss how the kindergartens utilize the potential for job-embedded professional learning.

The study is based on semi-structured interviews with five kindergarten managers in a medium-sized Norwegian municipality. Even though the study applies to a Norwegian context, the study’s findings could be recognizable to kindergartens managers and teachers in general. Furthermore, it can form the basis for reflection and discussion concerning professional learning and development among practitioners and professionals concerned with the quality of ECEC services across international contexts. We start by presenting some background information about kindergartens in Norway.

The Norwegian Kindergarten

Kindergartens in Norway are for children aged 0–5 years and are integrated into the national educational system (Haug & Storø, 2013). Children start compulsory school the year they turn six. Kindergarten is a voluntary scheme where children can stay while parents are at work or school. It is the municipalities that are responsible for kindergartens in Norway. The municipalities are obliged to offer a place in a kindergarten for children under compulsory school age that reside in the municipality (Ministry of Education & Research, 2020). Children have a statutory right to a place in a kindergarten from one year of age. In March 2020, 92.2% of children aged 1–5 years attended a kindergarten in Norway (Statistics Norway, 2020). Approximately 50% of kindergartens are privately owned and 50% owned by municipalities. Kindergartens are financed by public grants and parents’ fees. Municipalities are obliged to treat private owners equally with municipal owners as regards public funding. The amount parents pay varies based on their income. However, there is a maximum price for what parents pay for a full-time place in a kindergarten (Ministry of Education and Research, 2020).

Norwegian kindergartens differ in size and can be organized in different ways, but most institutions have a department structure and consists of several departments. The managers have the overall responsibility for the kindergarten as a whole, and a pedagogical leader is responsible for each department. Managers are given the responsibility for leading and following up processes for professional learning and development. They must motivate, inspire and facilitate the competence development among kindergarten teachers. Pedagogical leaders in collaboration with the manager are responsible for leading reflection and development work in their department (Ministry of Education and Research, 2013a).

The Norwegian Kindergarten Act states that managers and pedagogical leaders must be educated kindergarten teachers or have other tertiary level education that gives qualifications for working with children and pedagogical expertise. Kindergarten teacher education is a three-year university study with bachelor degree. According to regulations, there must be one pedagogical leader per 7 children under the age of three and per 14 children over the age of three. Pedagogical leaders work in teams with assistants to provide for groups of children. There is also a regulation for the ratio of children to staff. According to this regulation, there shall be maximum 3 children per staff when the children are under three years of age and maximum 6 children per staff when the children are over three years of age. Assistants can have a vocational training as child care and youth workers on upper secondary level (Ministry of Education and Research, 2020). In this article, all kindergarten employees are referred to as teachers.

All kindergartens in Norway must follow the Norwegian framework plan for the Content and Tasks of Kindergartens (Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training, 2017). This plan sets out the values and content of Norwegian kindergartens. New knowledge about children’s learning and development and the importance of childhood for the rest of the child’s life has contributed to increased national and international awareness of the work and role of kindergartens (White paper no. 41 2008–2009). Consequently, the responsibility of a kindergarten for children’s learning has become increasingly emphasized in recent years (Skjæveland et al., 2017). This has an impact on the requirements for competence and professional learning among kindergarten teachers. This is one of the main reasons why Norway has become interested in the kindergarten as a learning organization.

Theoretical Perspectives on Learning Organizations

Learning takes place in some sense in all organizations; however, the term “learning organization” is used to refer to organizations with specific characteristics when it comes to learning. Theorists have highlighted characteristics related to both organization, practice and culture (Palos & Stancovici, 2016; Wadel, 2008).

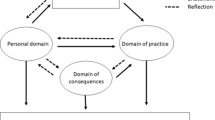

Senge (1990) emphasizes that learning organizations are organizations in which new and expressive thought patterns are nurtured and where people continuously learn, both individually and collectively, thereby expanding their capacity to create the results they truly want. A learning organization is an organization that is knowledgeable in creating, acquiring, sharing and transferring knowledge and that is able to apply this knowledge (Dalin, 1999; Garvin, 1993). A key feature of learning organizations is also a learning climate that allows for trial and error and time for reflection (Örtenblad, 2013). Learning and reflecting together, sharing knowledge and translating knowledge into behavior requires the establishment of learning relationships, i.e., relationships in which the parties mutually learn from one another. A learning organization is thus characterized by a diversity of learning relationships and the continuous development of new learning relationships (Wadel, 2002). Based on the above characteristics, key values in a learning organization are related to knowledge creation, sharing and application. Such learning-related values constitute the learning culture of a learning organization (Dymock & McCarthy, 2006).

A concept that has emerged from theories of learning organizations is professional learning communities. Such communities’ can be perceived as a key feature of a learning organization. The concept refers to collaborative activities of a group of professionals who learn together and develop shared meaning and purpose. The participants achieve personal growth as they work together to achieve what they cannot accomplish alone (Antinluoma et al., 2021; DuFour & Eaker 1998; Roberts & Pruitt 2003).

Elements that characterize a learning organization may be more or less present in a kindergarten (Skjæveland et al., 2017). Characteristic of a learning kindergarten is according to Norwegian policy documents that employees are engaged in creating and sharing knowledge on how to best work toward the organization's goals and by employees who are stimulated to see things in new ways and continuously explore how to learn together (Gotvassli, 2019a).

What Dalin (1999) calls close forms of learning, such as common reflection in daily work situations, have been highlighted as central to the development of a learning kindergarten (Gotvassli, 2014a, 2019a). Particularly important is a critical reflection on one's own attitudes, thinking and practice, and allowing for alternative ways of thinking and acting. Skoglund and Sundvall (2021) also emphasize connecting professional concepts to experiences and practice and further connecting experiences and practice to theory and research as a characteristic of learning kindergartens.

That kindergartens are learning organizations is crucial for kindergarten teachers' professional development. Professional development within ECEC contexts includes professional learning (Waters et al., 2018). We understand professional learning as job-embedded activities that increase kindergartens teachers’ knowledge and enable them to develop their practice (Darling-Hammod et al., 2009).

Practices for professional learning can include courses and training where kindergarten teachers acquire new knowledge and develop new skills. Furthermore, coaching that contributes to further developing existing skills and the development of teachers' confidence. In addition, mentoring where experienced professionals share their experiences with colleagues and guidance that stimulates kindergarten teachers' reflectivity. Through participation in such practices, the professional identity of kindergarten teachers is developed, i.e., their understanding of what is important for pursuing a professional practice of a profession (Heggen, 2005). Research related to schools supports that professional learning communities enhance teachers’ knowledge and skills and improve instructional practices and teacher efficacy for meeting children’s needs (Antinluoma et al., 2021; Keung et al., 2020). This indicates that the fostering of professional learning communities within kindergartens could be crucial in enhancing kindergartens teachers’ professional development and thus the quality for kindergartens.

Professional development among kindergarten teachers is about integrating professional learning with pedagogical practice. A particularly defining feature of professional learning in kindergartens is the participation in critical reflection to consciously explore one’s own practices (Waters et al., 2018). Teachers must be active agents in their own professional learning. Characteristics of a learning organization such as knowledge sharing, common reflection and group learning are job-embedded activities that ensure that kindergarten teachers become active agents in their own professional learning.

Methodology

Research Design

The present study is a qualitative study in which we have conducted interviews with kindergarten managers to obtain their understandings and thoughts about the kindergarten as a learning organization. We used semi-structured interviews where we looked for the informants' own experiences and understandings of the learning organization. Semi-structured interviews are neither an open interview nor a closed questionnaire-like interview (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2010, p. 47).

Qualitative interviews make it possible for informants to elaborate on their answers and can therefore provide access to rich data that enable the development of a deep understanding (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2015). The purpose of the study is to produce a richer picture of what characterizes the kindergarten as a learning organization. In this way, the study can contribute to transcending acknowledgement (Aase & Fossåskaret, 2007) and resonate with readers, even if it is based on few informants.

Data Collection

The data presented in the article originate from interviews with managers in five medium-sized kindergartens (approximately 50–70 children), four municipal and one is private, within the same municipality. This municipality had worked on the theme of a learning organization in joint meetings across kindergartens. For a period of four years, the municipality had focused on theoretical perspectives and discussions on the kindergarten as a learning organization for all employees. All involved kindergartens attended meetings once or twice a year.

The managers were chosen as informants because of their relevance to the research questions. They had all participated in the joint meetings across kindergartens related to the discussions about kindergartens as learning organizations. The selection of informants was thus criteria based (Schwandt, 2001). Three of the kindergarten managers were recruited through the head manager for kindergartens in the municipality, and two were recruited through direct contact with the kindergarten manager by email. The kindergartens have fictitious names to ensure the anonymity of the informants.

The length of the interviews ranged from 45 min to 1 h and 15 min. The interview guide was designed based on three sub-themes. These were related to the understanding of the concept of learning organization, what a kindergarten must be able to learn about and what characterizes a learning kindergarten. Both authors work in the kindergarten teacher education and are well acquainted with Norwegian kindergartens and thus have an insider position, which can strengthen the research process (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2015). The authors hold a PhD, one in social sciences and one in human resource development (HRD). Both authors participated in the interviews. The interviews were recorded on a separate recorder. The recordings were stored appropriately and deleted immediately after the transcriptions were completed.

Kvale and Brinkmann (2015) refer to an asymmetric power relationship between the researcher and the interviewee in an interview situation. This requires an ethical awareness on the part of the researcher. It was something we as researchers tried to strive for, by being aware of the role we played in the interviews. The informants were informed about the study’s purpose and provided written consent for the use of the interviews in accordance with the guidelines for research ethics developed by the Norwegian Research Committee (NESH, 2016).

Data Analysis and Interpretation

After the transcription, statements related to three main sub-themes were sorted out and stored in a separate document that formed the basis for our further analysis. These sub-themes were in line with our research questions and themes in the interview guide. Within the three themes, we highlighted what appeared to be the most prominent and frequently occurring topics in the data material. The fact that we have been two researchers that have discussed the empirical material has been important for the interpretation and analysis of the informants' statements.

We analyzed the data using a qualitative interpretive approach in line with a hermeneutic research tradition. In a qualitatively oriented research project like this, discovery and understanding are prioritized over verification. The researcher's own theorizing about observations and statements is central to the production of valid and credible knowledge. Our common theorizing about the informants' statements forms the basis for the analysis presented in this article. There is always a question of whether interpretations are credible and truthful and whether one interpretation is better than another (Schwandt, 2007). The fact that our interpretations are developed in dialog between us increases their relevance and reliability.

The purpose of the study was to investigate what according to kindergarten managers appears to be the characteristics of Norwegian kindergartens as a learning organization. Below, we have chosen to separate the presentation of empirical data from the discussion so that the reader has the opportunity to make an independent assessment of what the informants express. The findings are organized according to the sub-themes in the interview guide.

Findings

The kindergarten managers’ understanding of the term learning organization in a kindergarten context are presented, also what they perceive that it is important that a kindergarten acquires knowledge about, and what makes a kindergarten a learning organization.

Kindergarten Managers’ Understanding of a Learning Organization

According to the Norwegian framework plan, the kindergarten should be a learning organization. Hence, we asked the managers about their understanding of the kindergarten as a learning organization. The manager of the Rock kindergarten responded as follows: “In general, when I think about a learning organization, I think about reflection first and foremost. We spend a lot of time on this—in different meetings and forums. At all times, we have to reflect on new things that happen.” The manager of the Lake kindergarten pointed out “kindergarten-based learning” as part of the kindergarten being a learning organization and linked it to “… introducing more reflection into our meetings.” The manager at the Creek kindergarten replied: “For me, it’s about movement.” She notified that they had been working with the concept of a learning organization at the municipality level for a long time and that this had resulted in the term “movement.” The manager of the Pine kindergarten contributed the following thoughts about a learning organization: “I think you have to be brave. You have to dare and you have to think in new ways—and dare to do things differently.” The manager of the Spring kindergarten stated that “we would like to replace a learning organization with a playful organization. … Because playing means, after all, that you learn—and that you are developing in a way.”

To summarize, we see that the managers express somewhat different understandings of a learning organization. It is an organization characterized by reflection, courage, innovation, movement and development.

What must a Kindergarten Learn About?

Three themes emerged when the managers were asked what it is important for kindergartens to learn about. First, themes related to children and the staff's competence in working with children. The manager of the Creek kindergarten referred especially to “children’s appropriation, sleep and inclusion.” Other themes included how to greet children at arrival to the kindergarten, transitional situations, the meal as a learning arena, children's play, adult participation in play, language development and language stimulation and, more generally, knowledge of children’s development, interests and behavior and knowledge of when to take extra action in relation to a child.

Secondly, it was stated that the kindergarten teachers must learn about themselves, their relationship with the children and their relationship with each other. It was pointed out that teachers must be conscious of their own attitudes and that they must “dive into” and examine their own practice. Teachers must be aware of how they interact with the children and conscious of their adult role. The teachers must also learn from each other. According to the managers of the Spring kindergarten, it is about “sharing, that we dare say what we think—and that one dares to ask, why did you do it that way?”.

Third, the kindergarten must be learning in relation to its own organization and surroundings. The manager of the Rock kindergarten stated that the kindergarten must focus on itself and ask such questions as, “Where are we now and where do we want to be? What should we continue with and what should we change?” In addition, the manager of the Creek kindergarten thought it was important for the kindergarten “to be able to move in line with the requirements from the outside and the market.” Kindergartens must, according to the managers, also have expertise in culture.

The managers presented many examples of development work in their kindergartens. These include projects with external partners aimed at developing the competence of teachers related to, for example, diversity and inclusion. In addition, there are many internal projects related to such issues as leadership, the adult role, the participation of adults in outdoor play and the development of arenas for professional discussion and reflection among teachers. The managers also provided several examples of projects aimed at the children and some collaborative projects with parents.

What Characterizes a Learning Kindergarten?

When it comes to what characterizes a learning kindergarten, the managers emphasized the sharing of experiences and learnings between teachers, such as between a new graduate and an experienced kindergarten teacher. One of the managers stated that they practice staff circulation between departments and that this contributes to “new ideas … new relationships and new understandings of how one can work in different ways.” Teachers also learn from collaboration with the Pedagogical-Psychological service that visits the kindergarten and guides teachers with regard to those aspects they experience as challenging in working with children.

Three of the managers emphasized the value of having teacher education students as interns in the kindergarten. One of them put it this way: “We have students interning here and we find that we learn much from them. The students have all this new information based on new literature.” Another manager said: “They [the students] ask questions … We learn from them all the time. It is important to have students because we become more theoretical and we hear what the students learn and reflect on at the university.” The students bring updated and new knowledge into the kindergarten. Student questions challenge kindergarten teachers, forcing them to reflect on and express knowledge that otherwise, might not be expressed. Consequently, this learning relationship helps the kindergartens become a more learning organization when the teachers are able to stop and reflect on their own practice based on the student questions.

The most significant characteristic of a learning kindergarten that the mangers pointed at was reflection, especially during meetings. The manager of the Rock kindergarten said: “Getting the teachers to reflect more is something we are working on to put in system. Staff meetings, department meetings, etc.—how can we make these meetings a better learning arenas….” Reflection during these meetings is, according to the manager of the Creek kindergarten, linked to the new framework plan, recent research and their own practice. Kindergartens also try to make reflection a natural part of day-to-day practice but emphasize that this can be demanding. The manager of the Lake kindergarten said: “We try to achieve this… I see that some are able to do this because they have confidence in each other… but then there are others who need a little more time to pull someone aside because they are afraid that there are some toes that will be stepped on.”

Discussion

In this section, we highlight and discuss three key findings in our study: the managers' varied understanding of a learning organization, the lack of a holistic approach to development and learning, and reflection in everyday situations as an untapped opportunity for learning.

Divergent Understandings of a Learning Organization

Although a learning organization has been a central concept in kindergarten policy documents in Norway since 2006 (Skjæveland, 2019) and has been the subject of several joint meetings in the municipality, the managers involved in the study have a varied understanding of the concept. This is in line with previous studies that have shown that managers have an unclear understanding of the term (Gotvassli & Vannebo, 2016; Gotvassli, 2014b). The varied understanding of the concept learning organization expressed by Norwegian kindergarten managers may be related to, among other things, that the literature on learning organizations is comprehensive, relatively general and theoretical and does not provide a clear explanation of what a learning organization is (Dymock & McCarthy, 2006; Örtenblad, 2018).

The managers in our study relate their understanding of the concept of a learning organization primarily to teachers learning and development, such as innovative thinking, emphasizing reflection and daring to do things differently. Thus, their understanding is in accordance with the Framework Plan, which links kindergartens as a learning organization to employees’ reflection on academic and ethical issues (Norwegian Directorate of Education & Training, 2017, p. 15). Thus, we find little support to studies that have shown that Norwegian managers link kindergarten as a learning organization primarily to children's learning (Gotvassli, 2019b; Skjæveland et al., 2017). However, we will argue that competence development among the kindergarten teachers need to relate to their work with children. The concept of a learning organization in a kindergarten context therefore needs to expand in relation to how the term is usually used where it is linked exclusively to the learning among the organization's employees (Senge, 1990).

The kindergarten in our study had worked with the concept of movement in joint meetings within the municipality. Movement can be seen as a common denominator for the managers' understanding of a learning organization. To dare to think in new ways and do things differently and to be a playful organization involves movements that contribute to development and change. Reflection, critical thinking and the use of professional language can be regarded as movements that contribute to a new understanding, which in turn can lead to a movement that manifests in changes in practice. Thus, a learning organization can be understood as an organization that is constantly moving (Gotvassli, 2020, p. 137), moving toward more learning (Senge, 1990), movement in the form of knowledge creation, knowledge sharing (Dalin, 1999; Garvin, 1993) and in the form of building a learning culture and the corresponding organization of learning (Wadel, 2008).

Despite the fact that movement can be considered a common denominator in the managers’ understanding of a learning organization, they have problems clarifying what this means in practice for the kindergarten. Although the managers have worked with the concept of learning organization in joint meetings, they have not been able to give the concept a clear content. This may have affected kindergartens’ ability to develop into a more learning organization and can explain why Norwegian kindergartens have not come even further in developing into a learning kindergarten, although it has been a political goal that the kindergarten should be a learning organization for close to two decades.

Lack of a Holistic Approach to Development and Learning

Learning about children, pedagogical work, and changes in society appear as important learning areas in the kindergarten and should thus be a central part of the content of kindergarten teachers’ professional learning according to our study. These are issues that have been expressed in various public documents that the kindergarten must be learning in relation to (Ministry of Education and Research, 2016, Ministry of Education Research, 2013b). This means that kindergarten teachers must stay up to date and develop their competence and be able to reflect on their own practice, especially their relationships with children and each other. Furthermore, kindergarten must find ways to adapt to new demands, expectations and societal changes and thus bring about continuous learning and development.

The managers in our study referred to a variety of development and learning processes ongoing in kindergartens. These are both simple and comprehensive processes, short-term and long-term, and often very different. The diversity of processes is linked to the many different expectations and requirements that the kindergarten must meet, especially from the authorities and kindergarten owners. The underlying value basis for the development processes initiated in kindergartens is not stated by the managers. The processes appear to be loosely connected to each other and without a clearly stated overall goal or vision. There is no clear direction in the development work. The development processes highlight dissimilar approaches to development and learning in kindergartens. Norwegian kindergartens therefore appear to be highly contrasting as learning organizations. Based on the managers’ statements, the kindergartens must constantly comply with new requirements, expectations and changes in the market. Due to this, kindergartens do not seem to have a clear learning agenda, one that provides an overview of what knowledge they need in order to meet present and future challenges (Wig, 2018).

Consequently, it seems that the kindergartens tend to initiate too many diverse processes and become uncritically involved in too much. There seems to be a lack of a holistic and systematic approach related to how the kindergarten works on development and improvement. There is therefore a significant risk that kindergartens can become overloaded (Fullan, 2001) with too many parallel processes and that this will prevent deep learning (Fullan et al., 2018). There seems to be a lack of long-term projects that make it possible to dive deeply into consciously selected and central themes related to the daily practices that enable kindergartens to achieve professional learning that improve the quality of their pedagogical work.

Reflection in Kindergartens: An Unutilized Potential

Common reflection among the teachers emerges as what the managers consider a basic feature of a learning kindergarten. Reflective dialogue has been highlighted as a central element of learning communities within learning organizations (Roberts & Pruitt, 2003). The managers in our study highlighted staff meetings as the central arena for reflection and thus professional learning in the kindergarten. At staff meetings, reflection is often connected to the framework plan or professional literature and less to everyday experiences and pedagogical practices in the kindergarten. Linking reflection to the framework plan and professional literature is a way of reflecting together that can be very important for professional learning in the kindergarten. However, this reflection can easily become distant from everyday practice in the kindergarten and be perceived as something separate from the work to be performed in daily situations. This indicates that it is difficult for the managers to achieve a content in the professional learning within the kindergartens that is in accordance with what they promote that a kindergarten must learn about, such as the teachers’ own attitudes and practices and how they interact with the children and each other.

Reflections on experiences in everyday life situations in the kindergarten is something the managers want to see more of. They want to use practices and events from daily life in the kindergarten in the reflection process, but they express that this is difficult to achieve for practical reasons or to avoid that colleagues might feel stepped on.

This indicates that kindergartens are not able to sufficiently utilize what emerges as the most prominent and significant opportunity to develop into a more learning kindergarten. If kindergartens do not make reflection on their own practice a central part of staff meetings, while at the same time failing to incorporate reflection on their own practice in everyday situations, they do not utilize the tremendous potential for professional learning that may lie in such reflection. According to our study, kindergartens do not seem to be sufficiently aware of this learning potential. Furthermore, the kindergartens have not developed systems and routines for registering and systematizing everyday experiences and ensuring that these are the subject of reflection, enabling them to learn from them. Consequently, kindergarten teachers may not sufficiently develop their skills in reflecting, learning from reflections and using reflection as the basis for changing and improving practices and ensuring professional learning among them.

If the kindergarten is not capable of extensive reflection on everyday experiences and its own practice through “close forms of learning” (Dalin, 1999) in everyday situations and during meetings, it will miss the knowledge creation (Garvin, 1993) and shared learning (Senge, 1990) and other features of learning communities that are key to developing the kindergarten into a learning organization. Incorporated systematic reflection on everyday practice in the kindergarten seems to be the main factor that makes kindergartens appear as learning organizations.

Joint reflection on everyday practice in the kindergarten involves exploring this practice together. The kindergarten teachers examine and consider their own practices, attitudes and thoughts. Furthermore, through critical reflection, they question their own practices and the kindergarten's practices. In this way, they challenge practices and allow for alternative ways of thinking and acting. The purpose is to create increased awareness of and insight into existing practices and identify opportunities for an alternative practice. The reflections can contribute to thoughts and ideas that can form the basis for developing and changing practices and ensure that this is in line with the values and goals expressed in the kindergarten's framework plan.

Reflection as an incorporated part of both everyday life and staff meetings requires that managers and teachers become aware of the value and significance of such reflection for professional learning. Furthermore, it requires the development of individual and relational skills related to reflection. These are skills that must be automated so that it becomes second nature for teachers to stop and reflect on their own practices and those of colleagues. Furthermore, they must take what is learned from these reflections, and incorporate it into self-development processes and have it form the basis for organizational development processes in the kindergarten. This requires that kindergartens manage to build a learning culture in which joint reflection is a value that governs practice (Skoglund & Sundvall, 2021).

Conclusion

In this article, we examined what, according to Norwegian kindergarten managers, characterizes a kindergarten as a learning organization. A limitation of our study is that it is based on few informants. However, the study reveals some challenges related to the kindergarten as a learning organization that are important for professional learning and development within kindergartens. Furthermore, that are important to discuss and investigate further both in a Norwegian and international context.

Despite the fact that it has been a stated goal in Norwegian policy documents since 2006 that the kindergarten should be a learning organization, the managers in our study express a divergent and partly unclear understanding of the concept of a learning organization. This factor will affect kindergartens’ ability to develop into more learning organizations. Thus, we see that the fact that the concept of learning organization has not been sufficiently explained and elaborated in political documents has implications for achieving the goal that the kindergarten should be a learning organization.

Our study reveals that Norwegian kindergartens engage in a variety of learning and development processes. Based on our analysis, one of the challenges in the development of the kindergarten as a learning organization is to ensure a holistic and systematic thinking (Senge, 1990) and a direction to the movements that are initiated in the efforts to achieve and ensure professional learning and development. The kindergarten is characterized by many simultaneous developmental and learning processes, as well as rather limited and repetitive processes, therefore becoming less characterized by holistic and innovative processes.

A key feature of a learning kindergarten is that kindergarten teachers stop and reflect on their everyday experiences and comment on each other's practices. The kindergartens experience challenges when it comes to ensuring that teachers in everyday situations reflect on their own practices and relations, and the experiences they gain in performing daily tasks. Reflection is moved into meeting rooms. The reflections that take place during meetings are to a limited degree linked to the teachers’ practices and experiences in everyday life. This means that kindergartens struggle to organize learning so that the value of reflection on everyday experiences can be realized and maximized. The consequence is that kindergartens do not utilize the potential for professional learning and development related to reflecting on their own practices and experiences in everyday situations. Insufficient everyday reflection appears to be the main obstacle to developing kindergartens into more learning organizations and thus ensure sufficient professional learning among kindergarten teachers.

Implications one can draw from this study are first that it is crucial to work further within politics, education and kindergartens to develop a clear and common understanding of the concept of learning organization to increase the ability to develop the kindergarten into learning organizations. Second, the kindergarten must be careful about initiating too many different development processes at the same time so that they can ensure more systematic and thorough professional learning. Finally, kindergarten managers must work to develop a practice and culture that enables systematic reflection to become an incorporated part of kindergarten teachers’ day-to-day practice in everyday situations to ensure professional learning. Managers must facilitate and support teachers in stopping for short moments in everyday situations to reflect on their own experiences and practices. They must make sure that the teachers receive training in reflecting individually and together and are given the opportunity to practice this. As part of this, employees need to be trained in systematic observation. Managers can contribute to developing employees’ ability to reflect through systematic guidance, guided reflection in various situations and by being role models themselves. Furthermore, managers must work to build an organization where the employees trust each other and dare to ask questions about each other’s practices.

References

Aase, T., & Fossåskaret, E. (2007). Created realities. The production and interpretation of qualitative data. Universitetsforlaget.

Antinluoma, M., IIomäki, L., & Toom, A. (2021). Practices of professional learning communities. Frontiers in Educations, 6, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.617613

Dalin, Å. (1999). Paths to the learning organization. Cappelen Akademisk Forlag.

Darling-Hammond, L., Wei, R. C., Andree, A., Richardson, N., & Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional learning in the learning profession: A status report on teacher development in the United States and abroad. National Staff Development Council.

DuFour, R., & Eaker, R. (1998). Professional learning communities at work: Best practices for enhancing student achievement. National Education Service.

Dymock, D., & McCarthy, C. (2006). Towards a learning organization? Employee perceptions. The Learning Organization, 13(5), 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696470610680017

Fullan, M. (2001). The NEW meaning of educational change (3rd ed.). Teacher College Press.

Fullan, M., Quinn, J., & McEachen, J. (2018). Deep learning. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Garvin, D. A. (1993). Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 74(4), 78–91.

Gotvassli, K. Å. (2014a). The kindergarten as a learning organization—Theoretical perspectives. In S. Mørreaunet, K. Å. Gotvassli, K. H. Moen, K. Hoås, & E. Skogen (Eds.), Ledelse av en lærende barnehage. Bergen.

Gotvassli, K. Å. (2014b). The managers work with the kindergarten as a learning organization. In S. Mørreaunet, K. Å. Gotvassli, K. M. Moen, & E. Skogen (Eds.), Ledelse av en lærende barnehage (1st ed.). Fagbokforlaget.

Gotvassli, K. Å. (2019a). The kindergarten as a learning organization—Theoretical perspectives. In S. Mørreaunet, K. Å. Gotvassli, K. M. Moen, & E. Skogen (Eds.), Ledelse av en lærende barnehage (2nd ed.). Fagbokforlaget.

Gotvassli, K. Å. (2019b). The managers work with the kindergarten as a learning organization. In S. Mørreaunet, K. Å. Gotvassli, K. M. Moen, & E. Skogen (Eds.), Ledelse av en lærende barnehage (2nd ed.). Fagbokforlaget.

Gotvassli, K. Å., & Vannebo, B. I. (2016). The kindergarten as a learning arena and learning organization. In K. H. Moen, K. Å. Gotvassli, & P. T. Granrusten (Eds.), Barnehagen som læringsarena. Universitetsforlaget.

Gotvassli, K. Å. (2020). Quality development in kindergartens. From assessment to new pedagogical practice. Universitetsforlaget.

Haug, K. H., & Storø, J. (2013). Kindergarten—A universal right for children in Norway. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 7(2), 1–13.

Heggen, K. (2005). The place of professional knowledge in the professional identity. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 89(6), 446–460.

Keung, C. P. C., Yin, H., Tam, W. W. Y., Chai, C. S., & Ng, C. K. K. (2020). Kindergartens teachers’ perceptions of whole-child development: The roles of leadership practices and professional learning communities. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 48(5), 875–982. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143219864941

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2010). The qualitative research interview (2nd ed.). Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2015). The qualitative research interview (3rd ed.). Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

Manning, M., Gravis, S., Fleming, C., & Wong, G. T. W. (2017). The relationship between teacher qualification and the quality of the early childhood education and care environment. Campell Systemic Reviews, 13(1), 1–82. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2017.1

Ministry of Education and Research. (2013a). Competence for the kindergarten of the future. Strategy for competence and recruitment 2014–2020. Kunnskapsdepartementet.

Ministry of Education and Research. (2013b). The kindergarten of the future. Meld. St. 24 (2012–2013). Kunnskapsdepartementet.

Ministry of Education and Research. (2016). Time for play and learning. Meld. St. 19 (2015–2016). Kunnskapsdepartementet.

Ministry of Education and Research. (2017). Competence for the kindergarten of the future. Revised strategy for competence and recruitment 2018–2022. Kunnskapsdepartementet.

Ministry of Education and Research. (2020). Early Childhood Education and Care. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/families-and-children/kindergarden/early-childhood-education-and-care-polic/id491283/

NESH. (2016). Ethical research guidelines for the social sciences, humanities, law and theology. The national research ethics committees. Retrieved from https://www.etikkom.no/globalassets/documents/publikasjoner-som-pdf/60125_fek_retningslinjer_nesh_digital.pdf

Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training. (2017). Framework Plan for the Content and Task of Kindergartens. Utdanningsdirektoratet. Retrieved from https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/rammeplan-for-barnehagen-bokmal2017.pdf

Örtenblad, A. (Ed.). (2013). Handbook of research on the learning organization. Adaption and context. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Örtenblad, A. (2018). What does “learning organization” mean? The Learning Organization, 25(3), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLO-02-2018-0016

Palos, R., & Stancovici, V. V. (2016). Learning in organization. The Learning Organization, 23(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLO-01-2015-0001

Robert, S. M., & Pruitt, E. Z. (2003). Schools as professional learning communities. Corwin Press.

Saracho, O., & Spodek, B. (2006). Preschool teachers professional development. In B. Spodek & O. Saracho (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of young children (2nd ed., pp. 423–442). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline. The art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday.

Schwandt, T. (2001). Dictionary qualitative inquiry. Sage Publications.

Schwandt, T. (2007). Judging interpretations. New Directions for Evaluation, 114, 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.223

Skjæveland, Y. (2019). The kindergarten as a learning organization in a political context. In S. Mørreaunet, K. -Å. Gotvassli, K. H. Moen, & E. Skogen (Eds.), Ledelse av en lærende barnehage (2nd ed.). Fagbokforlaget.

Skjæveland, Y., Granrusten, P. T., Moen, K. M., Hoås, K., & Lillemyr, O. F. (2017). Leadership and learning in kindergartens. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 3, 239–251.

Skoglund, T., & Sundvall, P. (2021). Pedagogical leadership in kindergartens (2nd ed.). Universitetsforlaget.

Statistics Norway. (2020). Kindergartens. Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/barnehager

Wadel, C. (2002). Learning in learning organizations. Seek a/s.

Wadel, C. (2008). A learning organization. A relational perspective. Høgskoleforlaget.

Waters, J., Payles, J., & Jones, K. (Eds.). (2018). The professional development of early years educators. Routledge.

White paper no. 41 (2008–2009). Quality in kindergartens. Kunnskapsdepartementet. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-41-20082009/id563868

Wig, B. B. (2018). Learning organizations: Towards organization 5.0. Gyldendal.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University Of Stavanger.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The term kindergarten is in Norway used about publicly funded Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) institutions for children aged 0–5 years. In this article, we use the term manager about the kindergarten’s top leader, and we have taken the term teacher to include all adults who are charged, as part of their professional role, with the care and education of young children, regardless of whether they have a formal education as kindergarten teacher or not.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wadel, C.C., Knaben, Å.D. Untapped Potential for Professional Learning and Development: Kindergarten as a Learning Organization. IJEC 54, 261–276 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-021-00303-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-021-00303-w