Abstract

Wetland conservation increasingly must account for climate change and legacies of previous land-use practices. Playa wetlands provide critical wildlife habitat, but may be impacted by intensifying droughts and previous hydrologic modifications. To inform playa restoration planning, we asked: (1) what are the trends in playa inundation? (2) what are the factors influencing inundation? (3) how is playa inundation affected by increasingly severe drought? (4) do certain playas provide hydrologic refugia during droughts, and (5) if so, how are refugia patterns related to historical modifications? Using remotely sensed surface-water data, we evaluated a 30-year time series (1985–2015) of inundation for 153 playas of the Great Basin, USA. Inundation likelihood and duration increased with wetter weather conditions and were greater in modified playas. Inundation probability was projected to decrease from 22% under average conditions to 11% under extreme drought, with respective annual inundation decreasing from 1.7 to 0.9 months. Only 4% of playas were inundated for at least 2 months in each of the 5 driest years, suggesting their potential as drought refugia. Refugial playas were larger and more likely to have been modified, possibly because previous land managers selected refugial playas for modification. These inundation patterns can inform efforts to restore wetland functions and to conserve playa habitats as climate conditions change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Seasonal and ephemeral wetlands are ecologically important across a variety of landscapes, providing habitat to aquatic species and food and water resources to terrestrial species (Leibowitz 2003; Tiner 2003; Bolpagni et al. 2019). These wetlands are typically inundated for only part of each year, with hydroperiods (i.e., durations of inundation) that can vary substantially from one wetland to another across small geographic scales (Calhoun et al. 2017; Davis et al. 2019). Climate-change impacts on biodiversity in upland embedded (Mushet et al. 2015), seasonal wetlands will likely be driven largely by changes in wetland hydroperiod and may be most readily discernible during periods of climatic extremes, such as droughts (Walls et al. 2013; Davis et al. 2019). In some cases, climate-change effects on wetland inundation may interact with legacy effects from past land-management practices, ranging from unintentional effects (e.g., wetland soil compaction from livestock trampling) to direct, intentional hydrologic and geomorphic alteration (e.g., ditching, dredging, or filling). As climate conditions change, some localized areas may change more gradually and thus serve as climatic refugia (Morelli et al. 2016), while sites of persistent wetness despite climatic drying may provide hydrologic refugia (McLaughlin et al. 2017). However, few studies have sought to identify potential hydrologic refugia for upland embedded, seasonal wetlands. Identification of such refugia could improve wetland management and climate adaptation, and potentially inform wetland restoration efforts.

In the semi-arid sagebrush-steppe ecosystems of the northern Great Basin, USA (in southern Oregon, southern Idaho, northern Nevada and northern Utah, USA), snowmelt, as well as direct precipitation and surface runoff from summer thunderstorms, collects in terminal wetlands, salt lakes, and playas. Playas are seasonal (ephemeral) wetlands that form in closed basins with a negative annual water balance and remain dry throughout much of the year (Rosen 1994). Playas are often associated with surface evaporites and concentrations of clay minerals that impede infiltration; thus, they may become flooded after small amounts of precipitation (Rosen 1994). Playas in the northern Great Basin typically retain shallow water (from a thin film of water to tens of centimeters) from late winter through early summer, after which evaporation dries them out (fig. 1). The degree of groundwater connectivity, if any, for most playas in the region is unknown (Dlugolecki 2010), but a 3-year study in which a playa was equipped with piezometers did not detect any subsurface soil saturation (Clausnitzer et al. 2003). In the northern Great Basin, playas exhibit considerable seasonal and inter-annual variability in inundation extent and timing and unlike more southern Great Basin playas, they often support diverse vegetation and are not saline (Dlugolecki 2010). According to J. Moffitt with the Natural Resources Conservation Service in Redmond, OR (personal communication, May 28, 2019), while some large “lakebed” playas in the northern Great Basin are characterized by seasonally inundated hydric plant communities, many playas are inundated less predictably and are ringed by encroaching upland shrubs. Furthermore, playas in the northern Great Basin differ from those in agricultural regions (e.g., Great Plains) in that they are largely embedded in sage brush steppe with uniform land use (i.e., grazing or range conservation). Widespread declines in playa inundation in Great Plains playas have been linked to agricultural conversion, road building, and even conservation easements (Cariveau et al. 2011; Bartuszevige et al. 2012; Tang et al. 2015; Tang et al. 2016; Tang et al. 2018), whereas trends in inundation for northern Great Basin playas – and the role of livestock operations in these trends – are largely unknown (Dlugolecki 2010).

Dry playa viewed (a) from the ground and (b) in aerial imagery. In (b), the playa to the north has not been modified, whereas the playa to the south has a berm and pit (“dugout”), indicated by the black arrow, that were constructed to provide water to livestock. Image in (a) by M. Russell; aerial imagery (b) courtesy of Esri world imagery basemap

When inundated, some of these seasonal wetlands teem with aquatic invertebrates that provide a rich food source for migrating birds (O’Neill 2014). Cumulatively, hundreds of small playas throughout the northern Great Basin may be important spring migration habitats for shorebirds, providing resting and foraging opportunities as stepping stones between large marsh complexes (Dlugolecki 2010; Oring et al. 2013). Later in the season, some moist playa soils support grasses, sedges, and forbs that provide forage for wildlife including pronghorn (Antilocapra americana), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), and Greater sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus). Greater sage grouse, a federally-listed species of concern, sometimes use playas as leks (strutting grounds) and depend on the diverse forage and associated insects that grow in some playas when upland communities have already desiccated (Dlugolecki 2010; Hagen 2011). In a survey of 70 central Oregon playas, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) technicians identified 159 vascular plants, 51 bird species, 13 non-bat mammal species, 12 bat species, and 62 species of aquatic macro-invertebrates (J. Moffitt, personal communication, May 28, 2019). Although little research has been conducted on playas in the northern Great Basin, studies from other regions suggest that playa wetlands are important to biodiversity across much larger areas than the playas themselves (Haukos and Smith 2003).

Because playa inundation is likely driven largely by precipitation, snowmelt, and evaporation, the water and food resources playas provide to wildlife may be vulnerable to droughts. Drought conditions in the northern Great Basin are projected to intensify under certain climate-change scenarios (Ahmadalipour et al. 2017), which may exacerbate the ecological consequences of drought (Crausbay et al. 2017), including shifting the status of many playas from seasonal to ephemeral, or ephemeral to dry. Additional consequences of drought include the degradation of ecosystem services associated with wildlife and migratory bird habitats. In this context, variable inundation patterns among playas could imply that a small subset of playas might provide important localized refugia from droughts, i.e., isolated patches of viable habitat and resources during droughts that might help sustain wildlife populations under increasingly dry conditions (Dickman et al. 2011; Hermoso et al. 2013; Selwood et al. 2015; McLaughlin et al. 2017). If so, identifying which playas potentially function as drought refugia could help managers anticipate and potentially mitigate drought impacts on playa ecosystem services.

Strategies for mitigating drought impacts on playa habitats may include addressing the ecological impacts of previous land-use practices. In the northern Great Basin, many playas have been hydrologically modified by constructing berms and digging pits (referred to as “dugouts”) to retain water for livestock later into the summer and fall (fig. 1b). Many playas on public and private lands with the potential for holding water were modified between 1950 and 1970, some with multiple dugouts, concentrating livestock impacts in sensitive playa habitats. This form of hydrologic modification may concentrate water in a small area in and around the dugout, preventing the playa basin from filling to capacity and altering the playa hydroperiod, with possible consequences for wetland productivity (Dlugolecki 2010). Subsequent desiccation of portions of the playa may lead to encroachment of invasive exotic grasses and silver sage (Artemisia cana) (Bureau of Land Management 2013), as well as a general reduction in water quality for any remaining ponded areas (Wyland 2013). Though dugouts allow for enhanced summertime water retention by reducing losses to evaporation, the deeper water, steep bathymetry and reduction of playa-inundated surface area may limit their functionality as habitat for all but a small number, and few species, of shorebirds.

The BLM Prineville District in central Oregon has implemented an experimental playa restoration program that involves filling dugouts, excluding livestock from playas, mowing silver sage to create opportunities for native grass recolonization, and removing encroaching juniper (Bureau of Land Management 2013). BLM hydrologic models suggest the resulting increases in wetted playa surface area will depend on the relationship between playa volumetric capacity and dugout volumetric capacity. For example, restoring a 5.99-ha (ha) playa with a 15.45% ratio of dugout-to-playa capacity was predicted to increase playa areal inundation by 20.98%, whereas restoring a 88.27-ha playa with a 0.45% ratio of dugout-to-playa capacity was predicted to increase playa area inundation by only 0.50% (Bureau of Land Management 2013). Restoration may also decrease water availability late in the season due to increased shallow-water surface area and associated losses to evapotranspiration. Restoration may therefore represent a trade-off between improved playa conditions and forage for wildlife like sage grouse, versus negative impacts to other species that may have extended their ranges with artificial late-season water sources (J. Moffitt, personal communication, May 28, 2019). Researchers using remotely sensed soil conductivity found preliminary evidence of successful rewetting of playa basins following restoration (Reuter et al. 2013), but long-term effectiveness monitoring data are not yet available.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) land managers at the Sheldon-Hart Mountain National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) Complex in southern Oregon and northern Nevada (hereafter ‘the Refuge’), which no longer supports livestock operations and manages the landscape for conservation of a variety of wildlife and habitats (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013), are similarly interested in restoring some playas to more natural hydrologic conditions. Information is currently limited to help land managers understand where and why this highly intermittent water resource is available from year to year, such as drivers of playa inundation or spatial-temporal trends in playa inundation. Furthermore, land managers are tasked with conserving the key wildlife habitat features of playas despite projections of increasing summer drought severity across the northern Great Basin due to climate change (Ahmadalipour et al. 2017). Some future projections of climate variables for the Refuge for the years 2055 and 2085 suggest drier summer climate conditions for the Great Basin, primarily due to increased evapotranspiration (fig. 2) (ClimateWNA Map 2019). Though peak playa inundation occurs in the spring, increasingly dry summers may further constrain the hydroperiod and reduce the number of playas that do retain water into the summer – an extremely valuable ecosystem service in a water-scarce landscape.

CanESM2, CNRM-CM5, and HadGEM2-ES climate model predictions for (a and b) Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge in 2055 and 2085, and (c and d) Hart Mountain National Wildlife Refuge in 2055 and 2085, represented as changes from 1971 to 2000 historical means. Climate variables represented are: mean summer precipitation (MSP), annual heat-moisture index (AHM), summer heat-moisture index (SHM), reference evaporation (Eref), and climatic moisture deficit (CMD). All climate variables were obtained from ClimateWNA (2019)

To better understand playa hydrology and inform Refuge restoration planning efforts, we addressed the following questions: (1) What are the trends in playa inundation? (2) What are some of the hydrological, land use, and landscape factors that influence inundation? (3) How is playa inundation affected by increasingly severe drought? (4) Are there particular playas that remain wet under meteorologically dry conditions and thus could provide hydrologic refugia during droughts? and (5) How are these refugial patterns related to playa modification? In addition to contributing to the body of knowledge on upland embedded wetlands in the region (Comer 2005), addressing these questions may assist land managers in considering potential restoration options and in managing playas so they continue to provide critical habitat for animal and plant species in a drier climate.

Methods

Study Area

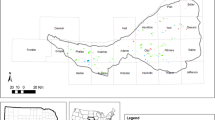

The Sheldon-Hart Mountain National Wildlife Refuge Complex (fig. 3) consists of two co-managed NWRs: Hart Mountain NWR (1093 km2) in southeastern Oregon and Sheldon NWR in northern Nevada (2321 km2). Hart Mountain NWR ranges in elevation from 1097 to 2458 m, consisting of a fault block ridge rising steeply from the west, with low hills and ridges descending gradually to the east. Sheldon NWR consists of rimrock tablelands, rolling hills, and gorges ranging in elevation from 1250 to 2195 m. Annual precipitation primarily in the form of winter snow and spring rain averages 305 mm for Hart Mountain NWR, and is slightly less for Sheldon NWR, with surface water in both refuges limited to springs, intermittent streams, and shallow playas. Soils and plants are typical of a high desert sagebrush-steppe ecosystem, and the land is managed for conservation of over 340 species of wildlife (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013). Playas on the Refuge (153 total) vary greatly in size, from approximately 0.5 ha to >1000 ha (mean 51.3 ha), although the majority (roughly two-thirds) of playas were < 20 ha. There is little variation in the playas’ soils (generally composed of silty clay or silt loam) or slopes (0–2%). The surrounding terrain commonly consists of very stony or cobbly loam, with small and subtly sloping (2–15%) catchments (Natural Resources Conservation Service 2020).

Modeling Factors that Influence Playa Inundation and the Effects of Drought

We evaluated time series of inundation patterns for 153 playas on the Refuge, roughly half of which were modified (contained dugouts), using remotely sensed presence or absence of surface water. Monthly surface-water data (30-m resolution) for the period February 1985 – October 2015 and covering all areas within the refuge boundaries were obtained from the Global Surface Water Explorer (GSWE) API (Pekel et al. 2016), a tool for visualizing water presence, seasonality, and persistence based on calibrated Landsat 5, 7, and 8. GSWE relies on an expert systems procedural decision tree to classify pixels as water, land, or non-valid observations using Landsat-derived multispectral and multitemporal attributes. Equations in the decision tree were determined by visual analytics derived from a spectral library of the three classes across a wide variety of conditions, as well as images enriched by Normalized Difference Vegetation Index and Hue-Saturation-Value transformations. For pixels that could not be assigned to a class because of spectral overlap, evidential reasoning was used, taking into consideration geographic location and temporal trajectory in establishing likelihood of water presence. Validation by Pekel et al. (2016) integrated visual confirmation of over 40,000 randomly selected points distributed geographically, temporally, and across sensors. Overall errors of omission were reported as less than 5%, with overall errors of commission less than 1% (Pekel et al. 2016). Given that no playas were smaller than a 900-m2 Landsat pixel – the smallest (0.5 ha) is covered by five pixels – the spatial resolution of the surface-water data was adequate.

We hypothesized that playas would be responsive to local climatic conditions, and that inundation of an individual playa may also be related to its size and modification history. We thus modeled playa inundation with the following covariates: playa size (m2), modification status (dugout presence/absence), and Standardized Evapotranspiration Precipitation Index (SPEI). We obtained monthly SPEI data (4-km resolution) from the West Wide Drought Tracker (Abatzoglou et al. 2017). SPEI subtracts monthly evapotranspiration (based on average monthly air temperature) from monthly precipitation to create a simple water balance. SPEI ranges from −5 to 5 and is standardized such that a value of 0 represents the long-term average conditions for a site, negative values indicate conditions drier than the long-term average, and positive values indicate wetter-than-average conditions. We represented climatic moisture conditions for each year using October 12-month SPEI (SPEI-12), which integrates climate conditions from November of the previous year through October of the year in question. Shapefiles representing playa borders, area, and modification status were provided by the USFWS.

After re-projecting and stacking the data in R (R Core Team 2018), we calculated the areal percentage of each playa that was wet at each monthly time step (February through October, 1985 through 2015; an example is shown in Appendix A). Data from November through January were commonly not available due to cloud cover and were not used. To examine annual wetted duration, we calculated the number of months (zero to 9) in each year that each playa held any amount of water. Data exploration revealed high frequencies of zero values for both monthly percent wet and annual wetted duration. We therefore fit Generalized Linear Mixed-Effects Models (GLMMs) to both datasets using the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015) in R, with SPEI-12, playa area, and playa modification status as covariates. GLMM modeling was performed in the following sequence: (1) determination of optimal random and fixed-effects structure based on computed Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values; (2) model averaging to produce parameter estimates (necessary when no combination of fixed effects results in a model with substantially lower AIC); and (3) estimation of marginal and conditional R2 to quantify predictive power of the best model (lowest AIC) in each of the two model sets.

Overdispersion, or variance larger than the mean, in the monthly percent wet data due to high frequencies of zero values was addressed by converting percentages to a binomial distribution (i.e., water presence/absence) (Zuur et al. 2009). We reasoned that this binomial representation of water availability was ecologically justified because even a small amount of observed inundation could potentially represent valuable habitat given the minimum surface-water detection size of 900 m2 (i.e., a single 30-m × 30-m Landsat pixel) and the general aridity of the landscape. In addition, conversion to a binomial distribution eliminated concerns that “percent wet” would be less accurate for the smaller playas represented by as few as five Landsat pixels. We used a Poisson distribution to model annual wetted duration (measured as a count of total months wet); no modification was necessary to address overdispersion. We rescaled continuous predictor variables (SPEI-12 and playa area) by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation to facilitate direct comparison of model coefficients and to aid in model convergence.

GLMMs account for autocorrelation in time-series data by explicitly modeling correlation of subsamples within sampling units (i.e., groups) in the context of a user-specified random-effects structure. We used a unique identifier for each playa nested within Refuge units (i.e., Hart Mountain NWR or Sheldon NWR) as the grouping variable in our analyses. Iterative inclusion of random slopes for each predictor variable to allow for heterogeneity among groups in the influence of fixed effects did not improve model fit based on AIC values, indicating that the “random intercept-only” model represented the optimal random-effects structure. Accordingly, we fit random intercept-only models with all combinations of fixed effects to determine the optimal fixed-effects structure (Zuur et al. 2009). Because no combination of fixed effects resulted in substantially lower AIC for either model set, we then used model-averaged parameter estimates and associated 95% confidence intervals (estimated from weighted unconditional standard errors) as our basis for inference; if the 95% confidence interval for a fixed effect overlapped zero, we concluded a non-significant effect. Next, we estimated values of marginal and conditional R2 to quantify predictive power of the best model (lowest AIC) in each of the two model sets (Nakagawa and Schielzeth 2013).

To examine how playa inundation is affected by increasingly severe drought, the GLMM models for water presence (binomial) and water duration (Poisson) were fitted with the 12-month SPEI values representing historical average conditions (SPEI = 0), moderate drought (SPEI = −1.0), severe drought (12-month SPEI = −1.5), and extreme drought (12-month SPEI = −2.0), following thresholds on drought severity used by Yu et al. (2014) and Ahmadalipour et al. (2017). The binomial model was used to determine the mean probability of predicted wetness in each scenario, and the Poisson model was used to determine the mean predicted months wet per year in each scenario.

Identification of Hydrologic Refugia during Droughts

To identify playas that might serve as hydrologic refugia during droughts (i.e., a small subset of playas that might hold water even under the driest conditions in our dataset), we began by identifying the 5 years (from 1985 through 2015) that had the lowest observed playa inundation (fewest numbers of wet playas) in the study area. Although we selected these years based solely on observed playa inundation patterns, we also used October SPEI-12 to confirm that these years adequately represented meteorological drought conditions for the study area.

We reasoned that in the 5 years of scarcest playa inundation, the few playas that did retain water might serve as potential refugia (water and/or food sources) for wildlife during droughts. In particular, we sought to identify refugia that demonstrated temporal stability across multiple drought years. For each playa, we calculated the number of years wet (from zero to 5) and the average number of months wet during each of the 5 driest years. We classified playas as potential drought refugia if they remained wet in all 5 of the driest years and held water for at least 2 months on average during the 5 driest years. After identifying playas that served as possible drought refugia, we asked whether these playas were generally represented by playas that consistently held water each year across a range of climate conditions, i.e., whether playas that were generally wet under average weather conditions could be used to identify refugial playas during droughts. To that end, we calculated the total number of years each playa was wet (defined as any amount of wetness for any length of time) from 1985 through 2015, excluding the five dry years. We then compared these patterns (“all other years”) to the playa inundation patterns for the 5 driest years to determine if inundated playas in average years explain the drought response. Finally, we examined relationships between drought-refugia metrics (number of years wet and average number of months wet during the 5 dry years) and playa size using Spearman correlations, and relationships of these metrics with modification status using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results

The number of wet playas across the Refuge varied by month and year, with playa wetness generally peaking in spring (March through May) as a result of rainfall and snowmelt and declining over the course of the summer (fig. 4). At several time points in the dataset, no playas were observed inundated, i.e., all were dry (Table 1). On average (across the months of February through October, from 1985 through 2015), approximately 19% of the 153 playas across the study area were inundated. Notably, a maximum of only approximately 62% of playas were wet at any given time point (in April 2006), meaning that slightly more than 1/3 of the playas were dry even in wet climatic conditions. A total of 49 out of 153 playas (32%) had no observed inundation at any time point in the dataset. The remaining 104 playas were inundated an average of 41% of years during April and 20% of years during September.

Factors that Influence Playa Inundation

AIC values and associated AIC weights (wi) used for model averaging of both the water presence (binomial) and water duration (Poisson) model sets are presented in Table 2. Model convergence was achieved for 79% of models. In both models sets, model-averaged parameter estimates were statistically significant (i.e., confidence intervals did not overlap zero) for SPEI and modification status, but not playa area (fig. 5a). SPEI was positively related to water presence (fig. 5a) and water duration (fig. 5b), indicating that wetter climate conditions increased the probability and seasonal length of playa inundation. Negative parameter estimates for modification status indicated that the probability of a playa holding water and its duration of inundation were significantly lower if it was unmodified.

Generalized Linear Mixed-Effects Model (GLMM) model-averaged parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals for water presence (a) and water duration (b). Variables include the Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), playa modification history (status: modified or unmodified), and playa extent in m2 (area)

The best models (lowest AIC values in Table 2) for water presence and duration produced low marginal R2 (0.11 and 0.10, respectively) but higher conditional R2 (0.78 and 0.82, respectively), indicating that there was considerable variation among playas in the presence and duration of water, and that accounting for that variation through the inclusion of a random effect substantially improved model fit.

Using the water presence (binomial) model with drought scenarios (i.e., SPEI-12 values indicating various levels of drought severity), the mean probability of a playa being wet across the full range of all other predictor variables declined from 22% (historical average), to 15% (moderate drought), to 13% (severe drought), to 11% (extreme drought) (fig. 6a). Similarly, using the water duration (Poisson) model with drought scenarios, the predicted mean number of months wet per year for a playa across the full range of all other predictor variables declined from 1.69 (historical average), to 1.20 (moderate drought), to 1.01 (severe drought), to 0.85 (extreme drought) (fig. 6b)

Using drought scenarios (i.e., Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI-12) values indicating various levels of drought severity), Generalized Linear Mixed-Effects Model (GLMM)-derived mean and standard deviation for (a) percent probability of predicted wetness for a playa, and (b) predicted months wet per year for a playa (out of 9 months), across the full range of all other predictor variables. Drought scenarios include: long-term, historical average conditions (SPEI = 0), moderate drought (SPEI = -1), severe drought (SPEI = -1.5), and extreme drought (SPEI = -2)

Refugial Playas during Droughts

We selected the years 1987, 1992, 2012, 2014, and 2015 to represent drought conditions based on playa inundation patterns (fig. 7, see dashed vertical lines in (a) and solid circles in (b)). Specifically, these were the years with the lowest average numbers of wet playas across the study area: from 9.1 to 13.1 playas were wet (averaged from February through October), compared to a mean value of 29.1 wet playas across all years, 1985–2015. These 5 years also had the lowest annual maximum number of wet playas (maximum in each year from February through October), ranging from 22 to 28, compared to a mean of 58 from 1985 to 2015. In general, playa inundation (represented both as mean annual and annual maximum number of wet playas) was positively associated with October SPEI-12 (fig. 7b). The 5 years that exhibited minimum playa wetness in the study area were characterized by moderate to severe drought conditions (all had October SPEI-12 < −0.8). Indeed, one of the selected years (1992) had the lowest October SPEI-12 value between 1985 and 2015 (−1.66, indicating severe drought), and three of the selected years (1992, 2012, and 2014) were among the 4 driest years in the study (all had October SPEI-12 < −1.4).

Selection of the five driest years of the study based on observed playa inundation. Time series plots in (a) depict the annual maximum (blue), annual mean (green), and annual minimum (brown) number of wet playas in the study area between February and October of each year. The five years with the lowest annual mean and lowest annual maximum number of wet playas are indicated by vertical dashed lines. These five years are depicted in (b) as closed, labelled circles; all other years are open circles. Relationships between numbers of wet playas and October SPEI-12 (Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index in October of each year using 12 months of antecedent climate conditions) are represented in (b), with annual maximum and annual mean numbers of wet playas in blue and green, respectively. Simple linear regression lines with R2 values quantify relationships between October SPEI-12 and playa wetness from 1985 to 2015

Nearly half of all playas (71 out of 153 playas; 46%) had no water in any of the 5 dry years selected for drought-refugia analysis. Of the remaining 54% that contained water in at least one dry year, 27% held water in at least 3 years, 15% held water in at least 4 years, and only 6% (nine playas total) held water in all 5 of the dry years. Notably, the nine playas that were wet in all 5 years were (by definition) wet in 1992, a year of severe drought in which the vast majority of playas on the refuge became dry (fig. 7).

The average number of months wet during the 5 dry years varied among playas, ranging from 0 to 6.8 months (fig. 8a). The majority of playas (105 out of 153; 69%) were wet in fewer than 3 of the 5 dry years and for less than 1 month per year on average during those years. Of the nine playas that held water during all 5 of the dry years, 6 of them (4% of all playas) also held water for at least 2 months on average during those years, meeting our criteria for drought refugia. These 6 playas appear exceptional in their history of providing water during drought conditions, and specifically during times when playa inundation is exceedingly scarce across the landscape.

Distribution of playas in the Sheldon-Hart Mountain National Wildlife Refuge Complex based on (a) the number of years wet and average months wet during the five driest years, and (b) number of years wet in the five driest years and number of years wet in all other years from 1985 to 2015. In (a), 71 playas (46%) had no observed inundation in any month during the five dry years. In (b), 49 playas (32%) had no observed inundation in any year from 1985 to 2015, including during the five driest years

Playas that were wet during most or all of the 5 driest years (i.e., with higher values on the horizontal axes of fig. 8) also tended to be wet during most other years (note absence of points in the lower right quadrant of fig. 8b). Thus, any playas identified as drought refugia based on dry-year analysis were also likely to be wet in other (non-drought) years. However, the reverse was not necessarily true: consistent wetness in all other years (i.e., higher values on the vertical axis of fig. 8b) did not always imply consistent wetness during dry years (note presence of points in the upper left portion of fig. 8b, representing playas that were generally wet in most years but often dried out during the 5 driest years). These results indicate that playas that were consistently inundated during non-drought years did not necessarily serve as drought refugia.

Based on Spearman correlation, larger playas were more likely to hold water during droughts: ρ(151) = 0.35, P < 0.001 for the relationship between playa size and number of years wet during the 5 driest years and ρ(151) = 0.36, P < 0.001 for the relationship between playa size and average months wet during those 5 years. In addition, modified playas held water for a greater number of years during the 5 driest years (F = 14.96, P < 0.001) and for more months on average during those driest years (F = 9.58, P < 0.01) compared to unmodified playas. Modified playas also were more likely to hold water during all years (1985 through 2015) across a range of climate conditions (F = 10.4, P < 0.01). Of the nine playas that held water in all 5 dry years, seven (78%) were modified. Of the 6 refugial playas (wet in all 5 dry years for at least 2 months on average), 5 (83%) were modified. Notably, modified playas also tended to be larger in size than unmodified playas (F = 9.83, P < 0.01). Collectively, these results suggest strong positive associations between playa size, modification status, and functional status as drought refugia.

Discussion

Interannual variation in weather conditions is a clear driver of playa inundation in this study area. Although groundwater connectivity of playas has not been rigorously studied in this region, we found that playa inundation is closely tied to local precipitation and evapotranspiration patterns, suggesting that playas in our study area may not be receiving large groundwater subsidies. Analysis of piezometer data from a playa roughly 100 km north of the study area similarly indicated lack of groundwater connectivity (Clausnitzer et al. 2003).

Our results confirm expectations that under drought conditions, managers can anticipate fewer playas to hold water and for those playas to be inundated for shorter seasonal periods. For example, during the dry years 2012 through 2015, in which October SPEI-12 ranged from −0.33 to −1.45, the number of inundated playas in our study area in July ranged from 1 to 9, compared to a July average from 1985 to 2011 of 26 inundated playas. Playa responses to droughts may have important implications in the context of regional concerns about drought intensification under climate change, i.e., droughts that may become longer, more frequent, and/or more severe. For example, Ahmadalipour et al. (2017) projected long-term changes in summer 3-month SPEI in the northern Great Basin under an RCP8.5 emissions scenario averaging a 0.02 unit decrease per year, equivalent to a decrease of 0.5 SPEI units over 25 years. In a future climate with drier summers and greater evaporative demand (see fig. 2), periodic droughts will likely exacerbate loss of ecosystem services and aquatic habitat provided by playas and may highlight the importance of the few playas that can provide drought refugia to wildlife. The ability of playa wetlands that have historically functioned as drought refugia to continue doing so in a drier future climate is unknown. Thus, conservation of playa-dependent plant and animal species may necessitate further study of the hydrogeologic and hydrogeomorphic properties of playas identified as potential drought refugia, including improved understanding of catchment elevations and slopes, catchment area to wetland ratio, surface area to volume ratio, playa bathymetry and soil characteristics, and possible shallow groundwater interactions (Parker et al. 2010; Bartuszevige et al. 2012). Such studies may also further explain the strong positive associations we observed between playa size, modification status, and functional status as drought refugia. In addition to intensifying droughts, climate change may also increase the likelihood of extreme precipitation events (Monier and Gao 2015), prompting researchers to consider the interactions between intensifying droughts, extreme precipitation events, and playa inundation.

Although playas of the northern Great Basin differ substantially from playas in other regions such as the Great Plains—in terms of climate, types of hydrologic alteration, and surrounding land use and vegetation—our findings suggest that some inundation dynamics in northern Great Basin playas may be similar to those of playas in other regions. Studies from Spain (Castaneda and Herrero 2005) and from the Rio Grande plains of Texas (Parker et al. 2010) have demonstrated substantial variability in inundation patterns both among playas and across years, which we also observed. Playa responsiveness to precipitation patterns and an overall tendency for larger playas to have greater likelihood of inundation were observed by Bartuszevige et al. (2012) and Cariveau et al. (2011) in the Great Plains as well as in this study. In addition, our finding that roughly one third of playas had no observed inundation at any time point in the dataset suggests that the hydrology of playas, or at least a subset of playas, may have been altered relative to historical conditions. In Great Plains playas, Tang et al. (2016, 2018) similarly found evidence that only a minority of playa wetland footprints actually experienced regular inundation and supported hydrophytic vegetation. Disentangling the hydrologic consequences of climate change (e.g., drought intensification) and legacy effects of land-management practices is challenging for playas in a number of regions, including in the northern Great Basin.

As managers plan for climate-change impacts to playa wetlands, they may simultaneously be considering hydrologic and ecological restoration efforts. Although we found that playas with dugouts were more likely to hold water, to retain water for longer periods, and to serve as drought refugia, we stress that correlation between modification status and observed playa hydrology does not reveal the nature or direction of causation. Indeed, far from being a randomly assigned treatment, playa modification may have been guided by natural variability in playa hydrology that was observed by previous generations of land managers. Although documentation of historical playa modification decisions by land management agencies and individual ranchers is scarce, we speculate that in many cases, land managers may have chosen to modify those playas that they noticed were consistently holding water from one year to another, and perhaps also playas that were observed to hold water in dry years. Such targeted modification could have benefited livestock operations by optimizing water retention on the landscape for a given amount of investment. If so, then the positive association we observed between modification status and playa inundation may be due at least in part to the historical selection of drought refugia as sites for modification.

Because water modifications for livestock are no longer needed to support grazing operations, Refuge managers are considering hydrologic restoration of some playas, which could include leveling berms and filling dugouts to create a smoother playa surface that more closely approximates the geomorphology of unmodified playas. Such restoration efforts would be aimed, in part, at increasing the geographic extent of playa surface inundation by preventing water from draining into dugouts. Although we did not perform a comprehensive assessment of dugout locations relative to playa wetness patterns, we noticed that not all dugouts are located within the most-inundated zones of their respective playas. Examination of two playas that held water in all of the 5 driest years (fig. 9) helps to illustrate several management considerations that are relevant to restoration planning. One playa (fig. 9a and b) has a dugout located within the zone of greatest wetness in the lowest-elevation area of the playa. In such a case, filling the dugout might reduce drainage of water from the playa surface and enlarge the inundated extent within the playa. However, in another example (fig. 9c and d), the dugout is located almost 3 m above the lowest area of the playa and is not within the most frequently inundated zone. In this case, it is unclear how dugout filling might affect playa hydroperiod and areal extent of inundation. This comparison underscores the importance of site-specific restoration planning and suggests how remote-sensing inundation analysis could help inform such planning efforts. Furthermore, restoration planners may need to consider playa area and the ratio of dugout-to-basin volumes. Large “lakebed playas” may provide more consistent water, emergent vegetation, and aquatic invertebrates than small “ponded clay playas,” which often have encroaching sagebrush (J. Moffitt, personal communication, May 28, 2019). However, relative gains in inundated area resulting from filling dugouts may be limited in large playas due to a low ratio of dugout volumetric capacity to playa volumetric capacity.

One example playa (a and b) showed inundation concentrated near the dugout location in (a) April and (b) July, averaged over 1985 through 2015. In this playa, the dugout is located near the lowest-elevation zone of the playa. By contrast, in another example (c and d), the dugout is not located in the areas of greatest wetness in (c) April or (d) July and is instead located almost 3 m higher than the lowest-elevation zone of the playa

Because playa modification was not a randomly assigned experimental treatment, our study was by nature observational, and hence it does not resolve the mechanisms by which modification may increase or decrease the ecosystem services provided by playas as water and food sources within the landscape, or as potential drought refugia. One future approach to addressing this question could involve incorporating a randomized experimental design into future playa restoration efforts. For example, if a randomly chosen subset of modified playas were assigned to undergo restoration as an experimental treatment (withholding all other modified playas as a control), then the effects of restoration on playa hydrology and ecosystem services could be rigorously assessed. Such considerations in the design of ecological restoration programs can increase the knowledge and insights gained from subsequent monitoring programs (Block et al. 2001). In addition, pre- and post-restoration field monitoring of ecosystem services provided by playas (e.g., migratory bird use, aquatic habitat and invertebrate food resources provided, late-season forage for terrestrial wildlife) could help ascertain the ecological consequences of attempts to restore playas to more natural hydrologic conditions. Finally, although we only calculated one-pixel (900 m2) inundation of playas from fewer than 1.4% of our total observations, we acknowledge we were not able to separate dugouts containing water from wet playas. Future studies incorporating data with higher spatiotemporal resolution could further refine our understanding of the relationships between playa inundation seasonality, hydrologic refugia, and modification status.

Conclusions

Playa wetlands are an understudied but important seasonal water and food resource for migrating birds and other wildlife that may be negatively impacted by climate drying and drought intensification. This study identified factors that influence playa inundation in the northern Great Basin, simulated the effects of intensifying droughts on playas, and identified a subset of playas that appear to function as hydrologic refugia during droughts. Historically, larger playas and playas with dugouts were more likely to provide drought refugia; however, the ability of these playas to function as refugia under climate change and in the context of hydrologic restoration efforts is unknown. To adequately prepare for climate-change impacts and assess possible implications of restoration, more research is needed on playa geomorphology and hydrogeology, potentially coupled with rigorously controlled experimental restoration studies and long-term monitoring of restoration effectiveness.

Data Availability

Data and code are available through Northwest Knowledge Network: https://doi.org/10.7923/bqhx-2e04.

References

Abatzoglou JT, Mcevoy DJ, Redmond KT (2017) The west wide drought tracker: drought monitoring at fine spatial scales. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 98(9):1815–1820. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-16-0193.1

Ahmadalipour A, Moradkhani H, Svoboda M (2017) Centennial drought outlook over the CONUS using NASA-NEX downscaled climate ensemble. International Journal of Climatology 37(5):2477–2491. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.4859

Bartuszevige A, Pavlacky M, Burris D, Herbener C (2012) Inundation of playa wetlands in the Western Great Plains relative to landcover context. Wetlands 32(6):1103–1113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-012-0340-6

Bates D, Machler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1):1–48 https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Block W, Franklin A, Ward J, Ganey J, White G (2001) Design and implementation of monitoring studies to evaluate the success of ecological restoration on wildlife. Restoration Ecology 9(3):293–303

Bolpagni R, Poikane S, Laini A, Bagella S, Bartoli M, Cantonati M (2019) Ecological and conservation value of small standing-water ecosystems: a systematic review of current knowledge and future challenges. Water 11(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/w11030402

Bureau of Land Management (2013) Sage-grouse playa management Environmental Assessment. U.S. Department of the Interior. NEPA Register: DOI-BLM-OR-P000–2012-0027-EA. U.S. Department of the Interior, Prineville, OR

Calhoun A, Mushet D, Bell K, Boix D, Fitzsimons J, Isselin-Nondedeu F (2017) Temporary wetlands: challenges and solutions to conserving a “disappearing” ecosystem. Biological Conservation 211:3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.11.024

Cariveau A, Pavlacky B, Bishop D, LaGrange C (2011) Effects of surrounding land use on playa inundation following intense rainfall. Wetlands 31(1):65–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-010-0129-4

Castaneda C, Herrero J (2005) The water regime of the Monegros playa-lakes as established from ground and satellite data. Journal of Hydrology 310:95–110

Clausnitzer D, Huddleston J, Horn E, Keller M, Leet C (2003) Hydric soils in a southeastern Oregon vernal pool. Soil Science Society of America Journal 67(3):951–960. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2003.9510

ClimateWNA Map (2019) http://www.climatewna.com/ClimateWNA.aspx

Comer P, Goodin K, Tomaino A, Hammerson G, Kittel G, Menard S, Nordman C, Pyne M, Reid M, Sneddon L, Snow K (2005) Biodiversity values of geographically isolated wetlands in the United States. NatureServe, Arlington, VA

Crausbay S, Ramirez A, Carter S, Cross M, Hall K, Bathke D, Betancourt J, Colt S, Cravens A, Dalton M, Dunham J, Hay L, Hayes M, McEvoy J, McNutt C, Moritz M, Nislow K, Raheem N, Sanford T (2017) Defining ecological drought for the twenty-first century. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 98(12):2543–2550. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-16-0292.1

Davis C, Miller D, Campbell E, Halstead B, Kleeman P, Walls S, Barichivich W (2019) Linking variability in climate to wetland habitat suitability: is it possible to forecast regional responses from simple climate measures? Wetlands Ecology and Management 27:39–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-018-9639-2

Dickman C, Greenville A, Tamayo B, Wardle G (2011) Spatial dynamics of small mammals in central Australian desert habitats: the role of drought refugia. Journal of Mammalogy 92(6):1193–1209. https://doi.org/10.1644/10-MAMM-S-329.1

Dlugolecki L (2010) A characterization of seasonal pools in Central Oregon’s high desert. Master’s Thesis, Department of Forest Resources, Oregon State University, Portland OR

Hagen C (2011) Greater sage-grouse conservation assessment and strategy for Oregon: a plan to maintain and enhance populations and habitat. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Salem, OR

Haukos D, Smith L (2003) Past and future impacts of wetland regulations on playa ecology in the southern great plains. Wetlands 23(3):577–589. https://doi.org/10.1672/0277-5212

Hermoso V, Ward D, Kennard M, Rouget M (2013) Prioritizing refugia for freshwater biodiversity conservation in highly seasonal ecosystems. Diversity and Distributions 19(8):1031–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12082

Leibowitz S (2003) Isolated wetlands and their functions: an ecological perspective. Wetlands 23:517–531. https://doi.org/10.1672/0277-5212

McLaughlin B, Ackerly D, Klos P, Natali J, Dawson T, Thompson S (2017) Hydrologic refugia, plants, and climate change. Global Change Biology 23(8):2941–2961. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13629

Monier E, Gao X (2015) Climate change impacts on extreme events in the United States: an uncertainty analysis. Climatic Change 131(1):67–81 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584–013–1048-1

Morelli T, Maher S, Nydick K, Monahan W, Ebersole J, Daly C, Dobrowski S, Dulen D, Jackson S, Lundquist J, Millar C, Redmond K, Sawyer S, Stock S, Beissinger S (2016) Managing climate change refugia for climate adaptation. PLoS One 11(8):E0159909. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159909

Mushet D, Calhoun M, Alexander A, Cohen J, DeKeyser K, Fowler L, Lane C, Lang M, Rains M, Walls S (2015) Geographically isolated wetlands: rethinking a misnomer. Wetlands 35(3):423–431 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-015-0631-9

Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H (2013) A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 4(2):133–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00261.x

National Resource Conservation Service (2020) Web soils survey. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved from https://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov.

O’Neill B (2014) Community dynamics of ephemeral systems: food web drivers, community assembly, and anthropogenic impacts of playa wetlands. University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, Dissertation

Oring L, Neel L, Oring K (2013) Intermountain west regional shorebird plan. Intermountain West Joint Venture.U.S, Fish and Wildlife Service, Arlington, VA

Parker AF, Owens PR, Libohova Z, Wu XB, Wilding LP, Archer SR (2010) Use of terrain attributes as a tool to explore the interaction of vertic soils and surface hydrology in South Texas playa wetland systems. Journal of Arid Environments 74:1487–1493

Pekel JF, Cottam A, Gorelick N, Belward AS (2016) High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 540(7633):418–422. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20584

R Core Team (2018) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: https://www.R-project.org/

Reuter R, Dlugolecki L, Doolittle J, Pedone P (2013) Using remotely sensed soil conductivity to monitor restoration activities on vernal pools, northern Great Basin, USA. In: Shahid S, Abdelfattah M, Kaha F (eds) developments in soil salinity assessment and reclamation: innovative thinking and use of marginal soil and water resources in irrigated agriculture, international conference on soil classification and reclamation of degraded lands in arid environments, pp 237–249

Rosen M (1994) Paleoclimate and basin evolution of playa systems. Geological Society of America Special Papers 289. doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/SPE289

Selwood K, Thomson J, Clarke R, Mcgeoch M, Mac Nally R (2015) Resistance and resilience of terrestrial birds in drying climates: do floodplains provide drought refugia? Global Ecology and Biogeography 24(7):838–848. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12305

Tang Z, Gu Y, Dai Z, Li Y, Lagrange T, Bishop A, Drahota J (2015) Examining playa wetland inundation conditions for National Wetland Inventory, soil survey geographic database, and LiDAR data. Wetlands 35(4):641–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-015-0654-2

Tang Z, Li Y, Gu Y, Jiang W, Xue Y, Hu Q, LaGrange T, Bishop A, Drahota J, Li R (2016) Assessing Nebraska playa wetland inundation status during 1985–2015 using Landsat data and Google earth engine. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 188(12):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-016-5664-x

Tang Z, Drahota J, Hu Q, Jiang W (2018) Examining playa wetland contemporary conditions in the Rainwater Basin, Nebraska. Wetlands 38(1):25–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-017-0953-x

Tiner R (2003) Geographically isolated wetlands of the United States. Wetlands 23:494–516. https://doi.org/10.1672/0277-5212

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2013) Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan and environmental impact statement. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Lakeview, OR

Walls S, Barichivich W, Brown M (2013) Drought, deluge and declines: the impact of precipitation extremes on amphibians in a changing climate. Biology 2:399–418. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology2010399

Wyland S (2013) Development of baseline data on Oregon’s high desert vernal pools. Master’s thesis, Oregon State University, Corvalis, OR

Yu M, Li Q, Hayes M, Svoboda M, Heim R (2014) Are droughts becoming more frequent or severe in China based on the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index: 1951-2010? International Journal of Climatology 34:545–558. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3701

Zuur A, Ieno E, Walker N, Saveliev A, Smith G (2009) Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. springer science and business media. NY, New York

Acknowledgements

MR was funded with a National Science Foundation Integrative Graduate Research & Education Research Traineeship through the University of Idaho Water Resources Department (Award # 1249400). JC was funded by the Northwest Climate Adaptation Science Center (project titled “Identifying and evaluating refugia from drought and climate change in the Pacific Northwest”). The authors wish to thank staff from the Hart-Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge Complex and the Bureau of Land Management Prineville District staff for their guidance and valuable discussions about land-use history. The authors also thank Andy Maguire, University of Idaho Ph.D. candidate, for assistance with project reconnaissance and outreach. This paper was improved based on review comments by Lee Vierling (University of Idaho) and four anonymous reviewers. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A

Appendix A

An example of how water presence / absence data at 30-m resolution were used to calculate percent wetness for each playa at each monthly time step. The year 1997 (a through d) was wetter than average, whereas 2015 (e through h) was drier than average based on Standardized Evapotranspiration Precipitation Index (SPEI). Percent wetness was subsequently converted to a binary value indicating water / no water for each playa in each time step.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Russell, M.T., Cartwright, J.M., Collins, G.H. et al. Legacy Effects of Hydrologic Alteration in Playa Wetland Responses to Droughts. Wetlands 40, 2011–2024 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-020-01334-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-020-01334-0