Abstract

This study explores the challenges of integrating macro, meso, and micro in the articulation of advanced innovation policy and examines, respectively, dimensions of public business support, intermediary organizations, and knowledge transfer. It conducts an integrative review of the pertinent literature and a bibliometric analysis of 440 articles. It reveals three major obstacles that seemingly impede the effective integration of macro, meso, and micro in contemporary policymaking and socioeconomic analyses: entrenched boundaries between different thematic areas, methodological discrepancies, and the relative lack of integrated theoretical models. These factors contribute to the absence of unified functional hubs focused on microlevel interventions. The proposed Institutes of Local Development and Innovation (ILDIs) could mitigate these challenges as they are presented as multilevel policy instruments intended to provide support to businesses—particularly to those facing chronic and structural problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In an era where socioeconomic development is increasingly influenced by the interplay between different levels of analysis and policy implementation, understanding the dynamics between macro, meso, and micro becomes critical (Lanahan, 2016; Vlados & Chatzinikolaou, 2020b). The current landscape highlights the urgency of integrating these levels to reinforce public support for businesses, effective intermediation, and sufficient knowledge transfer (Chen et al., 2023). This integration is essential for fostering a holistic approach to socioeconomic development, addressing both the overarching structural issues and the localized challenges faced by individual organizations (Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, 2022).

Past research has revealed “compartmentalization” problems in the mainstream socioeconomic discourse and policy approaches, critiquing the predominant focusing on either macroeconomic trends, mesolevel organizational frameworks, or microlevel individual behaviors. The seminal works of scholars like Nelson and Winter (1982), Galbraith (1987), and Dopfer et al. (2004) have underscored the entrenched boundaries among different thematic areas that have long hindered a comprehensive understanding of these interconnected levels. Methodological divergence, as highlighted by Barbour (2017), has further exacerbated a fragmented understanding, with different levels often requiring distinct research approaches. Α seeming absence of integrative, “macro-meso-micro,”Footnote 1 theoretical frameworks, as detailed by Zezza and Llambı́ (2002) and Mirzanti et al. (2015), likely leads to a noticeable void in policymaking, particularly in addressing the specific needs of less competitive microfirms, as indicated by Chatzinikolaou and Vlados (2022).

This paper aims to identify more clearly and address these gaps by conducting a thorough multilevel analysis of literature related to public business support, intermediary organizations, and knowledge transfer. It seeks to unravel the reasons for the limited integration of macro, meso, and micro in existing research and to identify new gaps that surface when these levels are collectively considered. The specific research questions are as follows:

-

(1)

What are the underlying reasons for the insufficient integration of macro, meso, and micro findings in research on public business support, intermediary organizations, and knowledge transfer?

-

(2)

What additional gaps arise from a multilevel synthesis of this literature, and why might a restructured macro-meso-micro approach be more adequate?

The subsequent sections of the paper are organized as follows: the second section introduces the concept of a macro-meso-micro synthesis and discusses the challenges in integrating these levels, focusing on the boundaries between different thematic categories and methods, along with the apparent absence of such holistic theoretical frameworks. The third section describes the methodology for the integrative review of 440 articles, detailing the literature search, inclusion criteria, bibliometric analysis, and critical evaluation. The fourth section presents the findings, exploring the apparent reasons behind the limited multilevel integration and examining specific macro-meso-micro policy frameworks as notable exceptions. The fifth section discusses these findings and their broader implications. The sixth section concludes the paper, emphasizing the necessity for integrated approaches in public support for business and policy formulation, and considers the potential of a policy proposal in addressing the identified gaps.

Theoretical Background

Macro-Meso-Micro Synthesis

The concept of an evolutionary macro-meso-micro synthesis provides a holistic framework for understanding socioeconomic development through interactions across various levels of perceptual and actual spatial scales. At least three significant obstacles seemingly hinder the effective integration of these levels—macro, meso, and micro—in current policymaking and socioeconomic analyses: entrenched boundaries across the various thematic categories, methodological differences, and the relative absence of integrated theoretical models.

The presence of “silos” among different thematic categories are likely an integration barrier. Grounded in evolutionary and institutional economics, the macro-meso-micro synthesis draws from different intellectual streams, challenging the traditional divide between microeconomics and macroeconomics (Galbraith, 1987, pp. 295–297). It incorporates the mesolevel as a pivotal connector of individual and systemic behaviors, addressing the shortcomings in classical macroeconomic interpretations (Dopfer et al., 2004, p. 68). Research such as that by Vlados and Chatzinikolaou (2020a, p. 115) on the ecosystems approach further illustrates the complex coevolutionary dynamics across these levels, moving beyond established notions of regional “growth poles” and industry “clusters.” However, different thematic categories often remain enclosed within their specific analytical boundaries—neoclassical and Keynesian economics often dwell on macrotrends, sociological studies probe mesoorganizational structures, and analyses of organizational behavior are the exclusive domain of microfactors (Nelson & Winter, 1982).

Advances in research methods, such as computational social science and big data analytics, hold promise for uncovering coevolving patterns across macro, meso, and micro (Barbour, 2017, p. 10). Nevertheless, a conventional fragmentation in methods—quantitative for macrotrends and qualitative for microlevel case studies—complicates the integration of conclusions, pointing to the need for a dynamic mesolevel approach that bridges the macro and meso (Barbour, 2017).

The third barrier is the relative dearth of integrative, macro-meso-micro, theoretical frameworks. While the conversation surrounding macro-meso-micro policy integration is in its infancy, there have been significant contributions that highlight the need for multilevel socioeconomic interconnectivityFootnote 2 to effectively tackle a range of developmental and innovational challenges including rural poverty, entrepreneurial resilience, and competitiveness in the realm of integrated industrial policy. Zezza and Llambı́ (2002 p. 1881) emphasized the importance of embedding meso and micro into macro in terms of policymaking, suggesting a framework to assess their interplay within given environments. Mirzanti et al. (2015, p. 407) illuminated the roles that individual entrepreneurs, organizations, and broader economic forces play across the spectrum of macro, meso, and micro, pinpointing essential conditions for entrepreneurial success such as psychological readiness, a culture of business innovation, and the fostering of competitive economies.

The triple helix theory, introduced by Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff (1995), serves as an integrative framework that suggests a synergistic relationship among universities, industries, and governments. This relationship underscores their interconnectedness and mutual influence in promoting innovation and wealth creation. Although the theory does not always explicitly employ a direct macro-meso-micro synthesis, this approach is implied. Etzkowitz (1996) further developed the framework, adopting an evolutionary perspective that connects the theory with regional innovation systems and proposes a coevolutionary relationship among institutional spheres.

As the theory evolved, it began to address the ongoing transition of innovation across socioeconomic organizations. Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff (1998) argued that such transitions do not have a fixed end point and expanded the concept to a global scale. However, critiques like those from Viale and Campodall’Orto (2002) have challenged the triple helix for its “fuzziness” and called for stronger interactions between academia and industry. Subsequent work by Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff (2000) further differentiated the triple helix from national innovation systems and mode 2 knowledge production, emphasizing its role in fostering interdisciplinary knowledge production structures.

The theory’s conceptual expansion continued with researchers such as Baber (2001) and Shinn (2002) exploring its implications for globalization and scientific disciplines. Notably, Carayannis and Campbell (2009, 2010) expanded the framework into a quadruple and quintuple helix by incorporating media, culture, and environmental dimensions, thereby enhancing its applicability to sustainable development and social ecology. Carayannis et al. (2018) recently expanded the framework to the concept of regional coopetitive business ecosystems through the quadruple and quintuple helix models. They proposed that these ecosystems are multilevel configurations of tangible and intangible elements. They significantly enriched the relevant scientific debate by underlining the need for multilevel governance and corresponding strategic knowledge processes to enhance regional innovation.

In the vein of creating integrated industrial policies, Peneder (2017, pp. 834–835) advanced the notion that effective policy must account for coevolution at all levels, with macrostrategies and mesodynamics collectively contributing to the attractiveness of a locale. Vlados and Chatzinikolaou (2020b, p. 8) went a step further with their “competitiveness web” concept, suggesting an ecosystem of interactions that unite firms, sectors, and economies into a cohesive, adaptive whole geared toward global competitive pressures. This concept delineates policy initiatives tailored to each level: microlevel policies targeting firm-specific advancements, mesolevel efforts aimed at invigorating regional innovation, and macroinitiatives designed to enact extended economic and societal reforms. Integral to this policy architecture are the “Institutes of Local Development and Innovation” (ILDIs), a policy proposal designed to synergize efforts between local governance, education systems, and businesses to bolster regional entrepreneurship and reinforce less competitive firms through a strategic six-step cycle (Chatzinikolaou & Vlados, 2022). This cycle begins with establishing a diagnostic system of the socioeconomic environment and progresses through the collection and synthesis of data, dissemination of local expertise, fostering innovation, enhancing local entrepreneurial capabilities, and culminates in the ongoing assessment of development outcomes.

Chatzinikolaou and Vlados (2022) detail how the suggested ILDIs can promote innovation through the “Stra.Tech.Man approach” (a blend of strategy, technology, and management), initially introduced by Vlados (2004). This approach compares firms to biological organisms, each with its unique “physiological” identity. Similar to how every organism possesses distinctive DNA that influences its growth and development path, each firm, regardless of size, has its unique foundational blueprint that guides its growth and development potential. The core of this approach is the Stra.Tech.Man synthesis, identifying three critical evolutionary aspects within which a firm operates: strategy, technology, and management. Though these aspects can be analyzed individually, they are intricately linked, forming the foundation of a firm’s capacity for innovative evolution, with the ILDIs positioned to bolster this innate potential.

Given that the macro-meso-micro analysis is still emerging, with only a few approaches identifiable through a preliminary literature review, it seems essential to bridge these gaps. Overcoming these challenges is vital for harnessing the complete potential of macro-meso-micro synthesis in advancing our understanding and promotion of socioeconomic development.

Public Support for Business, Intermediary Organizations, and Knowledge Transfer

Public support for business has long been a development staple, beginning with mercantilist policies in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries where states bolstered domestic industries through subsidies and protective regulations (List, 1856). The nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw the advent of industrial policies to foster key sectors (Peneder, 2017), and post-WWII policies shifted focus to bolster small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), recognizing them as growth catalysts (Bianchi, 2000). Contemporary policies prioritize innovation and research, acknowledging their role in enhancing economic returns (Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, 2022), and have evolved in the aftermath of globalization to aid businesses in international competition (Chen et al., 2023). Modern strategies increasingly mesh public support with sustainable development and social goals (Meyer et al., 2019).

The role of intermediary organizations traces back to medieval educational and professional guilds, precursors to modern universities, and professional services firms that facilitate knowledge transfer (Kangas et al., 2013; Wright & Kipping, 2012). The late twentieth century saw universities commercializing research through technology transfer offices (Bessant & Rush, 1995), while business clusters and networks primarily disseminate knowledge within the different industries (Howells, 2006; Yusuf, 2008). The triple helix framework has also emerged in intermediating policy activities, emphasizing innovation synergy between industry, academia, and government (Betz et al., 2016; Carayannis & Morawska-Jancelewicz, 2022; Johnson, 2008), and the digital age has ushered in online platforms that link knowledge creators and consumers (Abi Saad et al., 2024).

Knowledge transfer is a practice rooted in human history, evolving from hands-on apprenticeships to codified knowledge in various forms (Heilbroner, 1963). Knowledge transfer and technology transfer are often interchangeable concepts because both involve the dissemination of skills, information, and innovations; however, knowledge transfer encompasses a broader range of strategies and management approaches, extending beyond the technical realm to include organizational learning and intellectual capital (W. M. Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Vlados, 2019). The internet has revolutionized knowledge accessibility (Gates, 1999), and companies are increasingly leveraging open innovation and external collaborations (Chesbrough, 2003). Advances in big data and AI are further transforming knowledge exchange, particularly in data-centric industries (Schwab, 2016).Footnote 3

However, these three elements—public support for business, intermediary organizations, and knowledge transfer—are often considered in isolation. Yet, there are notable cases where these dimensions have successfully converged, as seen with the UK’s TECs (Training and Enterprise Councils), the EU’s industrial strategy, and France’s “Pôles de compétitivité” (Boocock et al., 1994; Cohen, 2007; Mazzucato et al., 2015). These examples reflect an integrated approach across levels: nationally or regionally devised strategies at the macrolevel, regional tailoring at the mesolevel, and direct knowledge dissemination at the microlevel. Although the TECs have ceased to exist, their model toward direct SME reinforcement through advice services provides valuable lessons on integrated approaches—the TECs were the late 1980’s organic continuation of the past UK workforce organization, the “Manpower Services Commission.” Yet, beyond their legacy lies a subtle issue: current frameworks such as the EU industrial policy and France’s “Pôles de compétitivité” show few clear signs of significantly aiding less competitive microfirms.Footnote 4 This indicates a possible issue as these smaller entities, less competitive than their SME peers, may not be receiving the supportive framework required within these structures. This incongruity necessitates further exploration to comprehend and remedy the lack of support for these critical, yet vulnerable, sectors of the economy.

Methodology

We conducted an integrative literature review in the fields of public business support, intermediary organizations, and knowledge transfer (Torraco, 2005). This approach, inspired by Torraco (2005) and informed by recent reviews such as Andrikopoulos and Trichas (2018), Jugend et al. (2020), and Crișan et al. (2021), involved systematic analysis of selected literature. The methodology comprised four main stages: literature search, inclusion criteria determination, bibliometric review, and critical analysis.

For the literature review, the Scopus database was chosen due to its comprehensive coverage of over 20,000 social science journals and its ability to export bibliometric data. In contrast, the Web of Science database includes fewer social science journals, which justifies the preference for Scopus (Harzing & Alakangas, 2016). Three literature searches were conducted from October 26 to November 4, 2023, focusing on specific terms within article titles, abstracts, and keyword: 1) “public support and business,” 2) “intermediate organization or intermediary organization,” and 3) “knowledge transfer and entrepreneurship.” Additionally, terms were also searched in UK English and were enclosed in quotes for specific phrases (e.g., “public support”).

Regarding inclusion criteria, no date restrictions were applied. The search results were refined by subject area (business, management, and accounting), source type (journal articles), and language (English). The initial search yielded 117, 176, and 173 results for the respective search terms. After filtering for available full texts, the totals were 108, 170, and 164, leading to 440 unique articles as only two duplicates appeared in the intermediate organizations and knowledge transfer (Sampedro-Hernández & Vera-Cruz, 2017; Szulczewska-Remi & Nowak-Mizgalska, 2023). Notably, the search terms “public support and business,” as well as “knowledge transfer and entrepreneurship,” were used to ensure comparability in dataset sizes as the terms “knowledge transfer and business” yielded more than 1000 results. Supplementary File 1 presents these literature sets in a table and an APA-listed format.

The bibliometric review mapped the origins and evolution of these sets. It helped discern trends based on which journals were most prominent in the sample, along with the thematic categories of the contributing authors, as revealed through a word-frequency analysis—this aspect of the study is elaborated upon in the next section. Additionally, the full texts from all sets were combined into a single file, enabling a frequency analysis of specific words related to methods discussed in the literature. The data from this frequency analysis were then visualized in graphs using spreadsheets, offering a clear depiction of the evolving patterns. This analysis aided in identifying factors that contribute to integration challenges, a topic first introduced in the previous section and elaborated upon in the next section.

The study concluded with a qualitative critical analysis, identifying explicit and implicit macro-meso-micro policy frameworks in the literature. This analysis pinpointed certain gaps and led to coherent policy proposal recommendations presented in the next section.

Results

Causes of Limited Integration

Boundaries Between Thematic Categories

The analysis of the entire sample reveals significant findings about the distribution of literature across journals in the three fields. Notably, journals like the “Journal of Technology Transfer,” “Research Policy,” and “Technological Forecasting and Social Change” stand out for their integrative scope, having published articles that encompass all three (Fig. 1).

The “Journal of Technology Transfer,” for example, exhibits a balanced distribution with five articles in public support for business, four in intermediary organizations, and 18 in knowledge transfer. “Research Policy” includes five in public business support, six in intermediary organizations, and eight in knowledge transfer. “Technological Forecasting and Social Change” displays two publications in public business support, nine in intermediary organizations, and nine in knowledge transfer. However, this multilevel trend is not widespread across the entire sample. Many journals have shown a preference or specialization in one field. Several journals, such as “Corporate Ownership and Control,” “Economic and Industrial Democracy,” and “Futures,” predominantly focus on a single field, typically intermediary organizations or knowledge transfer.

Only two publications, one by Sampedro-Hernández and Vera-Cruz (2017) on the role of entrepreneurs in the commercialization process through knowledge transfer intermediary organizations and another by Szulczewska-Remi and Nowak-Mizgalska (2023) on learning and entrepreneurship in the agricultural sector, appear in two of the fields. This fact highlights the ongoing challenges of integration in these.

In the analysis of specific term frequencies within the academic affiliations across the three sets, intriguing findings emerge. There appears to be a high concentration of certain terms within particular fields, indicating bounded integration among relevant thematic categories (Fig. 2).

For instance, “economics” is mainly found in the “public business support” literature (30%), indicating a traditional focus on broader economic trends and policies. Conversely, “business” and “management” are prevalent in all areas, particularly in the “knowledge transfer” field (32% and 19%, respectively), reflecting a focus on individual firms and internal processes. Despite these challenges, some terms in academic affiliations appear more frequently than others in all three fields. The term “innovation” frequently appears across all levels, especially in the “intermediary organizations” context (10%), signifying the growing acknowledgment of innovation as a link between microlevel entrepreneurial actions, mesolevel organizations and networks, and macrolevel economic development and policy. Similarly, “technology” appears frequently in the contexts of meso (15%) and micro (9%), suggesting a cross-subject approach to technology studies. The distribution of terms like “enterprise,” “industrial,” and “entrepreneurship” across the three levels indicates some integrational trends. However, the dominance of terms like “social” in macro and “business” in micro points to apparent lack of integrative structure between relevant thematic categories.

In conclusion, the trends observed reflect seeming boundaries and siloed nature prevalent in some of the examined fields, with some exceptions where integration is evident. Notably, fields like innovation and technology show integration, but the specific focus of certain terms (e.g., “economics” in macrocontexts) underlines ongoing challenges. These findings underscore the need for more comprehensive theoretical frameworks and methodologies to facilitate cross-subject research and policymaking, especially in creating a cohesive macro-meso-micro synthesis.

Methodological Differentiation and Variations

An analysis of frequencies in certain terms related to research methods reveals distinct preferences in approaches, indicating varying degrees of the sought after integration. These frequencies were extracted after merging the full texts of the entire sample (Fig. 3).

The term “regression” is used predominantly in macrocontexts (39%), indicating a preference for quantitative analysis at this level. In contrast, the mesolevel favors “interview” (57%), reflecting a qualitative, interpretive approach that focuses on individual or organizational perspectives. However, terms like “case study” and “qualitative” show a more balanced distribution, with higher frequencies in the micro (17% and 21%, respectively) and meso (17% and 13%, respectively) than in the macrocontext. This pattern suggests varying methodological integration across the three fields, particularly in efforts to understand and incorporate meso-micro into broader macroframeworks.

Macro-Meso-Micro Policy Frameworks

In the examined literature, an analysis concerning the application of a macro-meso-micro approach to policy points to notable instances, albeit few. These instances highlight ongoing integration challenges across the fields studied, while also suggesting the existence of certain valuable macro-meso-micro approaches worthy of attention.

Moreover, the literature review reveals instances where one-stop shops are effectively defined, like in Lambrecht and Pirnay (2005), which, despite offering valuable services, face challenges such as insufficient focus on SMEs’ unique qualitative needs. Liu et al. (2013) and Chen et al. (2015) describe entities that facilitate connections among small firms in bilateral or multilateral relationships, acting as agents in various innovation process aspects. Chen et al. (2023) note that these organizations are most effective when stemming from private-sector initiatives. While these approaches provide valuable information into the roles of intermediary organizations, they tend to overlook the integrative macro-meso-micro linkages.

However, there are initiatives in the examined literature that encompass various support mechanisms like grants, technology transfer, and research-development collaborations (Landry et al., 2013; Meyer et al., 2019; Mueller, 2023; Prodi et al., 2022; Sulej & Bower, 2006; Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, 2022). These programs primarily aim to foster an environment conducive to business innovation and growth, and we selectively present some important among them as follows:

-

(i)

At the macrolevel, initiatives like the US’ “Small Business Innovation Research” (SBIR) (Audretsch et al., 2002) and the Spanish “NEOTEC” program (Rojas & Huergo, 2016) have involved significant public sector actors, including federal ministries and national agencies. These actors have created policies and provided funds that aim to support a broad range of companies. However, these initiatives have often required the firms to have some level of existing capability or success, such as securing the first phase of SBIR funding (Lanahan, 2016) or having a developed technological potential.

-

(ii)

Intermediating organizations, such as the Canadian Precarn (Johnson, 2008) and the Italian AREA Science Park (Battistella et al., 2023), have served to connect smaller firms with larger networks, providing access to specialized knowledge and fostering open innovation capabilities. These intermediary organizations have been crucial for the diffusion of innovation and for bringing together various stakeholders, including SMEs, universities, and research institutions. Nevertheless, the focus have often remained on entities that are already somewhat established and capable of engaging with these intermediary organizations. The Chinese Keyi Web (Liu et al., 2013) is an organization that has focused on MSMEs, though it remains unclear whether this one-stop shop has been established as part of a broader development policy, through private initiatives, or by both.

-

(iii)

The transfer of core technology from academic institutions and the commercialization of federal research are among the main traits in relevant programs. They mainly indicate a focus on entities that are already engaged in innovation and technology development. Programs like UK’s “Knowledge Transfer Partnerships” (KTPs) (Wynn & Jones, 2019) and Canada’s iTMT (Abi Saad et al., 2024) have underscored the creation of supportive ecosystems and the encouragement of entrepreneurial activity, which are beneficial but may still not be tailored to the needs of the smallest and struggling firms.

We acknowledge a potential gap in supporting microfirms—particularly the less competitive ones. Most initiatives appear to assume a certain level of firm development and competitiveness, potentially neglecting firms not yet at this stage—Keyi Web being a possible exception (Liu et al., 2013). This indicates that while macro and meso receive attention through policy support and intermediation, the microlevel, particularly for less competitive firms, might not consistently receive the specialized, direct support necessary.

On a Restructured Synthesis of Development and Innovation Policy

The connection between development and innovation policy is not immediately apparent. Many macrolevel theorists often completely overlook innovation policy. It is usually more widely recognized at the mesolevel of different sectors or regions and at the microlevel by business theorists. However, effective development policy without innovation does not exist (Dosi, 1988; Edquist, 1997; Fagerberg et al., 2005; Freeman, 1987; Lundvall, 1992; Nelson & Winter, 1982; Schumpeter, 1942).

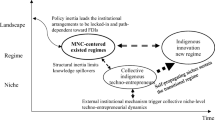

In response to this critique, we present the proposed policy of the Institutes of Local Development and Innovation (ILDIs), introduced in the Theoretical Background section. We highlight their role in a broader context of business support, placing them within a structured ecosystem that integrates interventions at the macro, meso, and micro levels (Fig. 4).

The development and innovation policy ecosystem, as adapted from Vlados and Chatzinikolaou (2020b)

This proposed initiative builds on Vlados and Chatzinikolaou’s (2020b) “competitiveness web” concept, advocating for an ecosystem of interactions that integrates firms, sectors, and other macrofactors. The macrolevel encompasses macrodynamic socioeconomic dimensions, from broader global dynamics to more specific demographic-environmental, cultural, and cognitive aspects. The formulation of national strategies to promote business support mechanisms must be at the forefront. This entails collaborative efforts between national ministries and agencies covering both macro and meso, creating a coopetitive environment that leads to mesolevel mechanisms for business support.

The mesolevel includes regional-local and sectoral dynamics, while the microlevel involves individual firms. It has been observed recently that actors and organizations that can contribute to business development remain quite uncoordinated, especially in less developed regional business ecosystems (Chatzinikolaou & Vlados, 2022; Rigg et al., 2021). These actors and organizations—which can be public, private, or mixed and arise from synergies among academic institutions, government interventions, and firms—include banks, business angels, venture capital firms, observatories, accelerators, technology transfer offices, coworking spaces, labor organizations, chambers of commerce, technology/science parks, incubators, and research centers (Bessière et al., 2020; Caird, 1994; Hackett & Dilts, 2004; Siegel et al., 2003). The ILDIs are proposed as key intermediate organizations in this ecosystem to coordinate these actors and organizations. Their proposed functions include the following:

-

(1)

Development observatory: Conducting continuous national-sectoral-local research to identify development prospects and periodical publishing of this intermediate organization’s outcomes.

-

(2)

Data analysis and synthesis: Facilitating collaborations among national and regional actors-organizations that potentially enhance entrepreneurship and evaluating investment opportunities for all involved socioeconomic organizations.

-

(3)

Local diffusion of expertise: Organizing business forums for knowledge exchange and dissemination of best practices.

-

(4)

Entrepreneurial “clinic”: Proposed as something different and more adaptable compared to other institutions like incubators and accelerators. It could offer free targeted consulting support to local organizations, especially those facing chronic and structural organizational problems—particularly in less-developed regional business ecosystems. This consulting could guide organizations to improve their business plans and subsequently achieve successful Stra.Tech.Man synthesis. This approach compares businesses to patients needing care as the ILDIs could “heal” long-term “ill” organizations—structurally deficient, relatively problematic, and lagging behind—and diagnose the prospects of healthier ones.

The specifics of how the ILDIs operate can be tailored to the individual ecosystemic needs. For instance, in a European context, they could establish offices in all NUTS-2 regions. The consulting process itself may also vary according to these tailored needs, possibly involving tax-funded private consultants to assist less competitive organizations in developing business plans. In essence, the ILDIs could function as a “developmental one-stop shop,” linking intermediate actors like an umbrella organization and providing public consultancy services to less competitive firms.

Τhe effectiveness of the ILDIs hinges on the acknowledgment that one-size-fits-all solutions are insufficient for addressing the diverse economic, political, cultural, and historical contexts globally. Ranging from the advanced economies in Northern Europe to the developing markets in the Balkans and Latin America, ILDIs require tailored strategies that consider the unique business ecosystems and intermediary-institutional structures of each region (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). The core of the ILDI model features the implementation of the Stra.Tech.Man approach, which integrates strategy, technology, and management into a unique mix that distinguishes it from traditional business support systems by acknowledging the specific “physiology” or unique “DNA” of firms, as stated earlier. This policy proposal is designed to employ an enhanced SWOT analysis that goes beyond standard approaches by emphasizing strategic flexibility and linking internal strengths and weaknesses with external opportunities and threats, utilizing principles of evolutionary economics (Vlados & Chatzinikolaou, 2019).

In conclusion, this integrative approach highlights complex ecosystemic relations in policy formulation, where government, industry, and academic institutions collaborate to monitor, analyze, and actively support business innovation and development. The proposal is sufficiently general to allow customization to specific national or international contexts, varying the degree of public support or intermediary actors. Political will is vital for implementing such wide-reaching interventions.

Discussion

This integrative review revealed that previous research has not fully integrated findings from macro, meso, and micro regarding policies on public business support, intermediary organizations, and knowledge transfer, primarily due to boundaries among different thematic categories and certain methodological differences. The articles in the sample demonstrated varying degrees of multilevel integration, with many of them focusing on only some of the fields under study, thus perpetuating silos among different thematic categories. The analysis also highlighted certain aspects of methodological divergence contributing to the relative absence of cohesive macro-meso-micro synthesis, with macrolevel research favoring quantitative methods like regression and mesolevel research leaning more toward qualitative approaches such as interviews. Additionally, a notable gap was the insufficient focus on less competitive microfirms in policymaking. Besides their relatively infrequent appearance in the examined literature, most macro-meso-micro initiatives are primarily designed for firms at certain level of development, often overlooking the specialized needs of smaller or struggling entities. This underscored the need for more comprehensive and inclusive policies that cater to the unique requirements across all levels, promoting a holistic approach to public business support, intermediary organizations, and knowledge transfer.

This study aligns with past literature, emphasizing entrenched boundaries among different thematic categories and methods as relative barriers in integrating macro, meso, and micro in socioeconomic policymaking and analysis. It resonates with challenges identified by scholars like Galbraith (1987) and Dopfer et al. (2004) regarding the difficulty of transcending silos among thematic categories and methods. However, it diverges in recognizing the often-ignored needs of less competitive microfirms. Despite literature stressing multilevel interconnectivity for addressing broad socioeconomic challenges (Mirzanti et al., 2015; Zezza and Llambı́, 2002), it often neglects these smaller entities. This study shows that most policies fail to support these firms adequately. Introducing the ILDIs, it proposes an integrated policy approach, as advocated by Vlados and Chatzinikolaou (2022), focusing on the microlevel through a holistic macro-meso-micro framework.

Contrary to initiatives that solely concentrate on well-established companies or high-potential startups (cf. Mueller, 2023), the ILDIs advocate for an inclusive approach that encompasses businesses at different stages of development and across sectors, promoting a dynamic adaptation process and facilitating a deep understanding of the socioeconomic and entrepreneurial ecosystems they aim to enhance. Overall, the ILDIs are distinguished by three main characteristics: their explicit targeting of the microlevel, their holistic macro-meso-micro perspective, and their broad focus beyond merely developed businesses or emerging businesses with high potential, such as startups.

Most policy support approaches for businesses tend to be dichotomous (Vlados, 2004). On one hand, macrolevel strategies, like growth poles, focus on regional development in a traditional sense (Vlados & Chatzinikolaou, 2020a). On the other hand, microlevel strategies, including incubators, knowledge and technology transfer offices, and accelerators, adopt a more limited business and management perspective. However, the main challenge in activating the proposed ILDIs lies in merging evolutionary economics with modern business management theories. The ILDI proposal marks a significant evolution from the triple helix model, drawing heavily on the work of Carayannis and Campbell (2009, 2010) to highlight the model’s potential for acknowledging diverse macro-meso-micro interactions. Moreover, the ILDI approach aims to address various developmental and innovation bottlenecks in localized socioeconomic contexts.

This study, like all research, has certain limitations. Methodologically, the exclusion of related concepts like procurement and technology transfer may have narrowed the analysis. Additionally, focusing solely on public business support, intermediary organizations, and knowledge transfer overlooks other potentially relevant fields. Using exclusively Scopus and academic articles could also limit the study’s applicability to broader literature. In terms of conclusions, while the research acknowledges the challenges of integrating literature across macro, meso, and micro due to boundaries among different thematic categories and methodologies, it may underrepresent other complexities. These include potential academic funding biases toward narrow-against-multilevel research, disparities in data availability across different scales, and the challenges posed by varying temporal and spatial scales.

Future research opportunities arise from these limitations. An expanded integrative analysis could include additional terms and concepts similar to those used in this study. Future studies could also consider a broader range of literature sources, including books and reports, to enhance the scope and reliability of findings. Additionally, potential new research could reexamine the issues beyond boundaries due to different thematic categories and methodologies. This could involve exploring the inherent complexities in synthesizing data and theories across different scales, assessing the impact of academic funding biases on the scope of research, examining disparities in data availability at macro, meso, and micro, and addressing the challenges in reconciling the different temporal and spatial scales at which these levels operate.

Conclusion

In this study, we extensively explored the integration challenges of macro, meso, and micro in the context of public support for business, intermediary organizations, and knowledge transfer. We identified key barriers to integration, including entrenched boundaries among different thematic categories and methods. Despite these obstacles, we noted that some macro-meso-micro theoretical frameworks in the examined 440 articles indicate a gradual, albeit subtle, move toward integrated policy approaches. However, we also highlighted that these longstanding barriers have hindered the creation of effective policy frameworks that meet the needs at all three levels, especially for smaller, less competitive firms.

Main takeaways center around the need for holistic, integrated approaches in public support and policymaking. The introduction of the ILDIs policy proposal offers a promising avenue for addressing these challenges. The ILDIs, akin to hospitals providing care to the sick, could serve as developmental one-stop shops, offering tailored support to businesses. They could potentially bridge gaps between government, industry, and academia, fostering an environment of collaboration and support. This integrative approach could be adaptable to various national or international contexts, allowing customization based on the degree of public support and intermediary actors required.

Notes

From this point forward, the term macro-meso-micro will be used without quotation marks.

We focus only on the macro-meso-micro synthesis as a framework for multilevel analysis, although we recognize that there are other relevant approaches (Gonzalez et al., 2018). Multilevel analysis can perceive developments at the levels of niches, sociotechnical regimes, and exogenous sociotechnical landscapes (Geels 2011; Perez 2004). Niches are the origin of radical innovations. The sociotechnical regime refers to the established processes of specific sectors and includes institutions, infrastructures, and regulatory frameworks that provide not only stability but also resistance to change. The exogenous sociotechnical landscape includes external factors that affect niches and regimes. The “higher” hierarchical levels exhibit more stable relationships than the “lower” ones due to greater number of actors and alignment among the elements.

In a university setting, the effectiveness of knowledge transfer appears to be hierarchical, with the following channels ranked in descending order of importance as per Agrawal and Henderson (2002): formal consulting, scholarly publications (including journal articles and conference papers), the industry employment of graduates, research collaboration, co-supervision of students, obtaining patents and licenses, engaging in informal discussions, and delivering conference presentations.

Microfirms, with 0–10 employees and annual turnovers of up to 100,000 US dollars (or two million euros in the EU definition), along with other MSMEs (microfirms and small and medium-sized enterprises), play a crucial role in the global economy: they represent around two-thirds of employment in developed countries, nearly 99% of businesses in the EU, and significantly impact employment and GDP in developing countries, contributing to over 50% of employment and up to 40% of national income (Singh and Venkata 2017).

References

Abi Saad, E., Tremblay, N., & Agogué, M. (2024). A multi-level perspective on innovation intermediaries: The case of the diffusion of digital technologies in healthcare. Technovation, 129, 102899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102899

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. London: Profile Books; New York, US: Crown Publishers.

Agrawal, A., & Henderson, R. (2002). Putting patents in context: Exploring knowledge transfer from MIT. Management Science, 48(1), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.48.1.44.14279

Andrikopoulos, A., & Trichas, G. (2018). Publication patterns and coauthorship in the Journal of Corporate Finance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 51, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2018.05.008

Audretsch, D. B., Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2002). Public/private technology partnerships: Evaluating SBIR-supported research. Research Policy, 31(1), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(00)00158-X

Baber, Z. (2001). Globalization and scientific research: The emerging triple helix of state-industry-university relations in Japan and Singapore. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 21(5), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/027046760102100509

Barbour, J. B. (2017). Micro/meso/macrolevels of analysis. In C. R. Scott, L. K. Lewis, J. R. Barker, J. Keyton, T. Kuhn, & P. K. Turner (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Organizational Communication (pp. 1–15). John Wiley & Sons.

Battistella, C., Ferraro, G., & Pessot, E. (2023). Technology transfer services impacts on open innovation capabilities of SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 196, 122875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122875

Bessant, J., & Rush, H. (1995). Building bridges for innovation: The role of consultants in technology transfer. Research Policy, 24(1), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(93)00751-E

Bessière, V., Stéphany, E., & Wirtz, P. (2020). Crowdfunding, business angels, and venture capital: An exploratory study of the concept of the funding trajectory. Venture Capital, 22(2), 135–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2019.1599188

Betz, F., Carayannis, E., Jetter, A., Min, W., Phillips, F., & Shin, D. W. (2016). Modeling an innovation intermediary system within a helix. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 7(2), 587–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-014-0230-7

Bianchi, P. (2000). Policies for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In W. Elsner & J. Groenewegen (Eds.), Industrial Policies After 2000 (pp. 321–343). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-3996-0_11

Boocock, G., Lauder, D., & Presley, J. (1994). The role of the TECs in supporting SMEs in England. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 1(1), 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb020928

Caird, S. (1994). How important is the innovator for the commercial success of innovative products in SMEs? Technovation, 14(2), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-4972(94)90097-3

Carayannis, E., & Campbell, D. (2009). “Mode 3” and “Quadruple Helix”: Toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. International Journal of Technology Management, 46(3–4), 201–234. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374

Carayannis, E., & Campbell, D. (2010). Triple helix, quadruple helix and quintuple helix and how do knowledge, innovation and the environment relate to each other? : A proposed framework for a trans-disciplinary analysis of sustainable development and social ecology. International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development (IJSESD), 1(1), 41–69. https://doi.org/10.4018/jsesd.2010010105

Carayannis, E., Grigoroudis, E., Campbell, D., Meissner, D., & Stamati, D. (2018). The ecosystem as helix: An exploratory theory-building study of regional co-opetitive entrepreneurial ecosystems as quadruple/quintuple helix innovation models. R&D Management, 48(1), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12300

Carayannis, E., & Morawska-Jancelewicz, J. (2022). The futures of Europe: Society 5.0 and Industry 5.0 as driving forces of future universities. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 13(4), 3445–3471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00854-2

Chatzinikolaou, D., & Vlados, C. (2022). Crisis, innovation and change management: A blind spot for micro-firms? Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-07-2022-0210

Chen, S.-H., Egbetokun, A. A., & Chen, D.-K. (2015). Brokering knowledge in networks: Institutional intermediaries in the Taiwanese biopharmaceutical innovation system. International Journal of Technology Management, 69(3–4), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2015.072978

Chen, X., He, Z., Jiang, T., & Xiang, G. (2023). From behind the scenes to the forefront: How do intermediaries lead the construction of international innovation ecosystems? Technology Analysis and Strategic Management https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2023.2182614

Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business Press

Cohen, E. (2007). Industrial policies in France: The old and the new. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 7(3–4), 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-007-0024-8

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393553

Crișan, E. L., Salanță, I. I., Beleiu, I. N., Bordean, O. N., & Bunduchi, R. (2021). A systematic literature review on accelerators. Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(1), 62–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09754-9

Dopfer, K., Foster, J., & Potts, J. (2004). Micro-meso-macro. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 14(3), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-004-0193-0

Dosi, G. (1988). Sources, procedures, and microeconomic effects of innovation. Journal of Economic Literature, 26(3), 1120–1171.

Edquist, C. (1997). Systems of innovation: Technologies, institutions, and organizations. Pinter. http://digitool.hbz-nrw.de:1801/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=1547263&custom_att_2=simple_viewer

Etzkowitz, H. (1996). A triple helix of academic–industry–government relations: Development models beyond “capitalism versus socialism.” Current Science, 70(8), 690–693.

Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (1995). The triple helix – University-industry-government relations: A laboratory for knowledge based economic development. EASST Review, 14(1), 14–19.

Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (1998). The endless transition: A “triple helix” of university-industry-government relations: Introduction. Minerva, 36(3), 203–208.

Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and “Mode 2” to a triple helix of university–industry–government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4

Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D. C., & Nelson, R. R. (2005). The Oxford handbook of innovation. Oxford University Press. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0620/2004276168-t.html

Freeman, C. (1987). Technology, policy, and economic performance: Lessons from Japan. Pinter Publishers

Galbraith, J. K. (1987). Economics in perspective: A critical history. Houghton Mifflin.

Gates, B. (1999). Business @ the Speed of Thought. Business Strategy Review, 10(2), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8616.00097

Geels, F. W. (2011). The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.002

Gonzalez, S., Kubus, R., & Mascareñas, J. (2018). Innovation ecosystems in the European Union: Towards a theoretical framework for their structural advancement assessment. Croatian Yearbook of European Law and Policy, 14, 181–217.

Hackett, S. M., & Dilts, D. M. (2004). A systematic review of business incubation research. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(1), 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTT.0000011181.11952.0f

Harzing, A.-W., & Alakangas, S. (2016). Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: A longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics, 106(2), 787–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1798-9

Heilbroner, R. L. (1963). The making of economic society. Prentice-Hall.

Howells, J. (2006). Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation. Research Policy, 35(5), 715–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.03.005

Johnson, W. H. A. (2008). Roles, resources and benefits of intermediate organizations supporting triple helix collaborative R&D: The case of Precarn. Technovation, 28(8), 495–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2008.02.007

Jugend, D., Fiorini, P. D. C., Armellini, F., & Ferrari, A. G. (2020). Public support for innovation: A systematic review of the literature and implications for open innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 156, 119985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119985

Kangas, S., Korpiola, M., & Ainonen, T. (Eds.). (2013). Authorities in the Middle Ages: Influence, legitimacy, and power in Medieval Society. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110294569

Lambrecht, J., & Pirnay, F. (2005). An evaluation of public support measures for private external consultancies to SMEs in the Walloon Region of Belgium. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 17(2), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/0898562042000338598

Lanahan, L. (2016). Multilevel public funding for small business innovation: A review of US state SBIR match programs. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(2), 220–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9407-x

Landry, R., Amara, N., Cloutier, J.-S., & Halilem, N. (2013). Technology transfer organizations: Services and business models. Technovation, 33(12), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2013.09.008

List, F. (1856). National System of Political Economy. Lippincott & Co J.B.

Liu, X., Shou, Y., & Xie, Y. (2013). The role of intermediary organizations in enhancing the innovation capability of MSMEs: Evidence from a Chinese case. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 21(SUPPL2), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/19761597.2013.819246

Lundvall, B.-Å. (1992). National innovation systems: Towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. Pinter Publishers

Mazzucato, M., Cimoli, M., Dosi, G., Stiglitz, J. E., Landesmann, M. A., Pianta, M., Walz, R., & Page, T. (2015). Which industrial policy does Europe need? Intereconomics, 50(3), 120–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-015-0535-1

Meyer, M., Kuusisto, J., Grant, K., De Silva, M., Flowers, S., & Choksy, U. (2019). Towards new triple helix organisations? A comparative study of competence centres as knowledge, consensus and innovation spaces. R and D Management, 49(4), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12342

Mirzanti, I. R., Simatupang, T. M., & Larso, D. (2015). Entrepreneurship policy implementation model in Indonesia. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 26(4), 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2015.072765

Mueller, C. E. (2023). Startup grants and the development of academic startup projects during funding: Quasi-experimental evidence from the German ‘EXIST – Business startup grant.’ Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 20, e00408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2023.e00408

Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press https://archive.org/details/knowledgecreatin00nona

Peneder, M. (2017). Competitiveness and industrial policy: From rationalities of failure towards the ability to evolve. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 41(3), 829–858. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bew025

Perez, C. (2004). Technological revolutions, paradigm shifts and socio-institutional change. In E. Reinert (Ed.), Globalization, economic development and inequality: An alternative perspective (pp. 217–242). Edward Elgar.

Prodi, E., Tassinari, M., Ferrannini, A., & Rubini, L. (2022). Industry 4.0 policy from a sociotechnical perspective: The case of German competence centres. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121341

Rigg, C., Coughlan, P., O’Leary, D., & Coghlan, D. (2021). A practice perspective on knowledge, learning and innovation–insights from an EU network of small food producers. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 33(7–8), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2021.1877832

Rojas, F., & Huergo, E. (2016). Characteristics of entrepreneurs and public support for NTBFs. Small Business Economics, 47(2), 363–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9718-9

Sampedro-Hernández, J. L., & Vera-Cruz, A. O. (2017). Learning and entrepreneurship in the agricultural sector: Building social entrepreneurial capabilities in young farmers. International Journal of Work Innovation, 2(1), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWI.2017.080723

Schumpeter, J. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy (Edition published in the Taylor&Francis e-Library, 2003). Harper & Brothers

Schwab, K. (2016). The fourth industrial revolution. Crown Business

Shinn, T. (2002). The triple helix and new production of knowledge: Prepackaged thinking on science and technology. Social Studies of Science, 32(4), 599–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312702032004004

Siegel, D. S., Waldman, D., & Link, A. (2003). Assessing the impact of organizational practices on the relative productivity of university technology transfer offices: An exploratory study. Research Policy, 32(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(01)00196-2

Singh, A., & Venkata, N. A. (2017). MSMEs Contribution to Local and National Economy (MicroSave – Briefing Note #168). MicroSave. https://www.microsave.net/files/pdf/BN_168_MSMEs_Contribution_to_Local_and_National_Economy.pdf

Sulej, J. C., & Bower, D. J. (2006). Academic spin-outs: The journey from idea to credible proposition – a combination of knowledge exchange, knowledge transfer and knowledge translation. International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies, 1(1–2), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijkms.2006.008847

Szulczewska-Remi, A., & Nowak-Mizgalska, H. (2023). Who really acts as an entrepreneur in the science commercialisation process: The role of knowledge transfer intermediary organisations. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 15(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-09-2020-0334

Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4(3), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283

Viale, R., & Campodall’Orto, S. (2002). An evolutionary Triple helix to strengthen academy-industry relations: Suggestions from European regions. Science and Public Policy, 29(3), 154–168. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154302781781029

Vlados, C. (2004). La dynamique du triangle stratégie, technologie et management: L’insertion des entreprises grecques dans la globalisation [The dynamics of the triangle of strategy, technology and management: The insertion of Greek enterprises into globalization] [Thèse de doctorat de Sciences Économiques, Université de Paris X-Nanterre]. http://www.theses.fr/2004PA100022

Vlados, C. (2019). Change management and innovation in the “living organization”: The Stra.Tech.Man approach. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 7(2), 229–256.

Vlados, C., & Chatzinikolaou, D. (2019). Towards a restructuration of the conventional SWOT analysis. Business and Management Studies, 5(2), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.11114/bms.v5i2.4233

Vlados, C., & Chatzinikolaou, D. (2020). From growth poles and clusters to business ecosystems dynamics: The ILDI counterproposal. International Journal of World Policy and Development Studies, 6(7), 115–126.

Vlados, C., & Chatzinikolaou, D. (2020). Macro, meso, and micro policies for strengthening entrepreneurship: Towards an integrated competitiveness policy. Journal of Business & Economic Policy, 7(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.30845/jbep.v7n1a1

Wright, C., & Kipping, M. (2012). The engineering origins of the consulting industry and its long shadow. In T. Clark & M. Kipping (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Management Consulting (pp. 29–50). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235049.013.0002

Wynn, M., & Jones, P. (2019). Context and entrepreneurship in knowledge transfer partnerships with small business enterprises. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 20(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750318771319

Yusuf, S. (2008). Intermediating knowledge exchange between universities and businesses. Research Policy, 37(8), 1167–1174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.04.011

Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J. M. (2022). Fostering regional innovation, entrepreneurship and growth through public procurement. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 1205–1222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00466-9

ZezzaLlambı́, A. L. (2002). Meso-economic filters along the policy chain: Understanding the links between policy reforms and rural poverty in Latin America. World Development, 30(11), 1865–1884. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00113-4

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Cyprus Libraries Consortium (CLC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chatzinikolaou, D., Vlados, C. Public Support for Business, Intermediary Organizations, and Knowledge Transfer: Critical Development and Innovation Policy Bottlenecks. J Knowl Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-02161-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-02161-y