Abstract

There is a growing need for a transition to green economic growth (GGDP) given that the current economic system is largely environmentally unsustainable. This study thus addresses GGDP enhancement in less developed countries using the case of Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA) countries where institutional deficiencies are typically at the root of most resource depletion and environmental degradation issues. Six institutional quality measures were used namely corruption control, government effectiveness, political stability, regulatory quality, rule of law, and voice of accountability while controlling for other factors like industrialization, energy use, and population growth in the region. The study applied a battery of second-generation panel econometric techniques in the empirical analysis after which both Bootstrap Quantile regression (BQR) technique and panel ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation approaches were applied to observe the variables' roles on GGDP advancement in SSA. From the findings, corruption control and government (policy) effectiveness favorably impact Green GDP in SSA. However, both rule of law and regulatory quality performed poorly as they were insignificant to GGDP enhancement. Furthermore, all control variables promote GGDP except for population growth. Thus, the findings buttress the need to strengthen institutions for effective governance and quality environmental regulations to enhance GGDP growth towards actualizing sustainable development goals (SDGs) in the SSA region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, national and international initiatives to promote green gross domestic product (green GDP) as a new source of growth have intensified in response to severe economic and environmental issues. Building on this momentum can expedite the progress toward sustainable development via improved energy efficiency, sustainable use of natural resources, and a robust ecosystem service valuation. Green GDP is a subject of economic policy that emphasizes policy for long-term development (Château et al., 2011: Adebayo et al., 2023; Gyamfi, Agozie et al., 2023; Gyamfi, Onifade et al., 2023; Adedoyin et al., 2023). It combines two essential imperatives: (a) ongoing inclusive GDP growth, which is much needed in less developed nations to combat poverty, inequality, and promotes general well-being, and (b) enhanced management of the environment, which is needed for the utilization of limited resources in the era of climate change challenges (Ali et al., 2023; Cubbage et al., 2010; Ofori et al., 2023). Following the introduction of green GDP as part of the 2008–9 economic stimulus packages, several governments witnessed enhanced job creation and improved incomes levels in the short term by increasing investment in green technologies (particularly low-carbon technologies). Thus, influencing others to also look at the fundamentals of green GDP. From an environmental standpoint, they focus on internalizing externalities in environmental issues through the incorporation of sustainable development goals into the frameworks of economic policies vis-à-vis resources utilization decisions. In the meantime, another imperative – the third one, has recently been stated in addition to the extant two imperatives namely equity and inclusion. This third imperative is particularly crucial for developing countries as it is expected that green GDP should also benefit those excluded from the economic system. Those excluded are mainly in the informal sector and developing countries, in particular, are known to have a large chunk of such exclusions.

In many developing countries, the informal economy is very substantial. As such, the potentials and risks of this sector must be factored into any plans for green GDP enhancement to provide better economic opportunities and boost inclusiveness for the poor. Besides, the understanding that the current economic system is unsustainable and wasteful in resource use and inequitable cost and benefit distribution is growing by the day (McIntosh & Renard, 2009). This relates to ending the unsustainable old habits as much as creating new green opportunities. Furthermore, systemic changes will be required to link better economic, environmental, and social policies together with institutions in identifying the required synergies as well as understanding the inherent trade-offs and uncertainties in different contexts. As a result, developing a policy framework for green GDP advancement on a national basis is a crucial activity. The OECD is now working on a report called Green GDP and Developing Nations, which will look at how developing countries might address the elements of a practical policy framework that is required to achieve the transition to green GDP (Tajuddin, 2018). The report considers policy instruments within the context of a green GDP, and how to cater for the differences in resources endowments, socio-economic development, the capacity of institutions, and the sources of economic growth. Such a framework encompasses environmental concerns and a wide range of economic and policy issues. Appropriate institutional arrangements must be in place for long-term investments and policies to deliver sustainable and equitable outcomes, and capacity development is also required to facilitate desired goals. Furthermore, to improve economic development in developing countries, institutional policies for the use and management of natural wealth must be strengthened.

Environmental pollution and ecological deterioration have arisen globally as impediments to societal and economic progress since the 1960s (Appiah et al., 2023). GDP has long been criticized for failing to capture genuine economic welfare since it ignores the costs of environmental degradation, natural resource depletion, and income inequity (Gan & Griffin, 2018; Mäler et al., 2008), as well as the value of non-market products and services (Yang & Poon, 2009). Indeed, there is growing awareness about ecosystem accounting (Gan & Griffin, 2018) to build green accounting systems and investigate the interdependence between the environment and the economy (Mäler et al., 2008). Some works have examined green GDP accounting around the world, for example, China's green GDP estimations on a regional basis, by removing the costs of negative environmental externalities from GDP as seen in Yang and Poon (2009). Also, for Wuyishan's green GDP where the values of direct ecosystem services were added to GDP as seen in Xu et al. (2010). Estimations were also done by compensating for natural resource depletion in addition to environmental destruction for Malaysia's green GDP calculation as seen in Vaghefi et al. (2015), and Thailand's green GDP (Mardones & del Rio, 2019). Furthermore, rapid global economic growth has been accompanied by massive changes in industrial structure (McMillan et al., 2011), which significantly impact pollutant emissions (Awosusi et al., 2022; Erdoğan et al., 2021, 2023; Haouas et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2017). Evaluations of sectorial green output value have also gotten much attention because the determination of sectorial environmental cost is a fundamental aspect of designing efficient policy for reducing greenhouse gases emission (Onifade, 2022; Wang et al., 2018).

In recent years, international efforts to address climate change and promote sustainable development have gained increased urgency. The 27th Conference of the Parties (COP27b) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held marked a crucial milestone in global climate action. The conference brought together world leaders, policymakers, scientists, and civil society representatives to discuss and negotiate strategies for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to the impacts of climate change. The outcomes of COP27b highlighted the need for transformative actions to achieve the targets set in the Paris Agreement and emphasized the crucial role of green GDP as a key indicator of sustainable economic growth. The conference underscored the importance of integrating environmental considerations into economic policies and highlighted the urgency of transitioning to low-carbon, resource-efficient economies. Against this backdrop, this research aims to contribute to the ongoing discourse on green GDP by examining the relationship between institutional quality and sustainable economic development, with a focus on less developed countries and the specific challenges they face in achieving their environmental and developmental goals. By addressing these pressing issues, this study aims to provide valuable insights and policy recommendations to support global efforts towards a sustainable and resilient future.

As a result, given the relevance of green GDP, the question of "how to achieve green GDP" has piqued the interest of many researchers (Chan et al., 2016). Institutional quality among other factors has been identified as an economic growth driver in much previous research (Anyanwu, 2014), but just a handful of studies examined its effects on emissions (Song et al., 2019). Some of the studies posit that institutional quality boosts green GDP as it links industries to new environmentally benign machinery to reduce environmental deterioration (Adams et al., 2018). Furthermore, while empirical evidence suggests that governance influences economic growth (Bekun et al., 2023; Çevik et al., 2020; Donelli & Chiriatti, 2017; Musah et al., 2023; Nwaka & Onifade, 2015; Sarpong et al., 2023), only a handful of studies attempted to link institutional quality to growth and carbon emissions simultaneously (Bekun et al., 2021; Salman et al., 2019).

Hence, in this study, we examine the roles of institutions in attaining Green GDP by utilizing six governance metrics. This study provides a significant contribution to the subject matter in the context of less developed countries such as the case of several economies in Sub-Sahara Africa. The study focuses on economies in Sub-Saharan Africa, where institutional deficiencies and lack of incentives are commonly identified as root causes of resource depletion and environmental degradation issues. By examining the link between institutional quality and green GDP in this specific context, the paper aims to shed light on the challenges and opportunities for sustainable economic growth in the region. The case study will provide valuable insights into the relationship between institutions, economic performance, and environmental sustainability in less developed countries, with a particular emphasis on Sub-Saharan Africa. We argue that economic performance and institutions should be judged on a broader set of criteria than traditional efficiency and equity goals, including 'green' GDP, environmentally-adjusted productivity growth, sustainability criteria, the incidence of social benefits, and costs (including extra-market values), and stakeholder analysis. The study will explore specific crucial policy approaches, focusing on the necessity for minimum safe standards (SMSs) in using natural capital to achieve sustainable development, maintain intragenerational equity, and safeguard critical natural capital (a version of the precautionary principle).

In addition, this research adds to the literature by examining the link between institutional quality and green GDP to provide useful policy recommendations for stakeholders. The approaches used in the study also create important contributions to the empirical literature by proposing a sustainable economic growth index based on a newly created green GDP measurement to ensure natural and observable economic success based on economic and environmental variables. Lastly, the study also aids policymakers in developing sound policy frameworks for achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in developing countries from the green GDP perspective.

Despite increasing recognition of the importance of green GDP and institutional quality in promoting sustainable economic development, there is a significant research gap when it comes to understanding their relationship, particularly in the context of less developed countries, such as several economies in Sub-Saharan Africa. This research problem serves as the foundation for our study. Therefore, the objective of this paper is to fill this gap by examining the roles of institutions in attaining green GDP in the specific context of Sub-Saharan African economies. The novelty of this study lies in its focus on less developed countries and its exploration of the relationship between institutional quality and green GDP. By conducting an empirical analysis and utilizing six governance metrics, we aim to provide valuable insights and policy recommendations for achieving sustainable economic growth and environmental sustainability in the region. Moreover, our study contributes to the literature by proposing a sustainable economic growth index based on a newly created green GDP measurement, which allows for a comprehensive assessment of economic and environmental variables.

Overall, this research not only addresses a significant research gap but also provides practical implications for policymakers and stakeholders in their pursuit of sustainable development goals. By understanding the link between institutional quality and green GDP, we can develop effective policy frameworks that promote environmentally friendly practices, resource conservation, and equitable economic growth in less developed countries. Such insights are essential for achieving the desired transformation towards a sustainable and inclusive future." The significance of this research lies in its contribution to knowledge regarding the relationship between institutional quality and green GDP, its provision of practical implications for policymakers and stakeholders in achieving SDGs, its proposal of a sustainable economic growth index, and its focus on the specific context of Sub-Saharan Africa. By addressing these aspects, the study aims to promote sustainable and inclusive development, facilitate environmental conservation, and guide decision-making towards a greener and more prosperous future.

Theoretical Foundations

Green GDP Theory

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) tends to be a poor calculation according to the principle of sustainable growth. Alternatively, economists are trying to create better structures to assess true welfare and sustainable growth. Green GDP also applies to such indices of welfare and the environment, such as the Comparable Green GDP (CGGDP), the Sustainable Economics Welfare Index (ISEW), and the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) have been used as new indicators of economic openness study. A more considerable trade is also related to higher economic growth and development (Çoban et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2019), thus, making trade a frequent theme on many governments' agendas. Although there is some evidence contrary to Wang (2011), this promotion of export-led growth seems to agree that higher growth leads to higher economic well-being and change. However, the paper of Li and Lang (2010) indicates contrarily that higher growth is also related to higher prices, which are instead adverse to the concept of green GDP.

In response to the shortcomings of the conventional gross concept of GDP in the early 1990s, the concept of 'green GDP' emerged to account for the economic costs of depleted natural resources and pollution that are affecting human well-being. GDP is usually defined as the total market value, including exports minus imports (net exports), of all final goods and services that are generated in a certain period (normally within a year). It has been used in national accounting as a conventional indicator of the size of an economy and is often wrongly viewed as a metric for change in public discourse. The term gross means the exclusion from the accounting of capital depreciation. For example, infrastructural depletions are not accommodated in the GDP but Net Domestic Product (NDP) and Net National Product (NNP) are used when such factors are considered. Since the 1990s, the notion of "green" GDP has gained some traction in academia and public policy. The People's Republic of China made one of the most notable attempts to introduce the idea. The Chinese government issued its green GDP in 2006, which was put together by the national environmental protection agency in collaboration with the efforts of the National Bureau of Statistics. The study estimated that economic losses from environmental degradation accounted for 3% of the country's GDP in 2004. The estimate included estimates of air, water, and solid waste emissions and the costs of depleting different natural resources.

Furthermore, as part of a larger community of sustainable development indicators, several other development metrics similar to green GDP have also been created. In the late 1980s, for instance, the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW) was created to fix the shortcomings in GDP. ISEW accounts for the environmental and social benefits of traditional and non-market economic transactions. Its importance is measured by the balance between positive transactions that support people's well-being and harmful economic activities that decrease them. The Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), later created by Redefining progress (a public policy non-governmental organization) in 1994, effectively contains the same indicators as ISEW. The key differences between the two are often due to data availability and users' expectations for valuation methods. International organizations, state entities, and academic researchers have used ISEW and GPI extensively.

Genuine Savings (GS), proposed in 1999 by the World Bank, is another popular development metric. GS predicts domestic savings lower the value of resource depletion and environmental degradation, taking both natural and human resources into account. The New Economics Foundation (NEF) adopted a relatively new metric, the Happy Planet Index (HPI), in 2006. HPI bypasses conventional monetary policies and focuses on the efficacy with which nations transform the use of natural resources into human and social well-being. In particular, HPI is the ratio (measured by ecological footprint) of happy life years (the result of life satisfaction and life expectancy) to environmental effects.

The Theory of Institutional Quality

With the work of North Douglas on institutions, the value of institutions and their effect arose in the 1970s. North (1994) stressed the significance of institutions, which argues that institutions provide an economy's incentive structure and form the course of economic movement towards growth, deflation, or decline as the structure develops. An institution may acquire different definitions. North (1994) sees institutions as structured and informal restrictions that are humanly devised by regulations, laws, constitutions and moral principles, norms, and self-imposed codes of conduct. Subsequently, the incentive structure of societies and economies are characterized by these formal and informal constraints, respectively.

North (1990) defines institutions and organizations by suggesting that organizations and entities form relationships. In an economy's structural evolution, organizations and their entrepreneurs are the players if organizations are the game's rules. Institutions are organized restrictions that guide human activity and organizations are groups of people tied together by a shared intent of accomplishing certain goals. To generalize the technique, it could be noted that two interacting parties need to be institutions and organizations, the first of which sets rules or transmits those already defined, and another party (i.e., organizations), acting in compliance with the rules defined.

Hodgson (2006), gives critical feedback on the suggested plan by North (1994) description of institutions that there are no synonyms for institutions and organizations. He begins by differentiating the critical characteristics of institutions and then uses certain features to equate organizations with institutions. In 2003, the World Bank defines institutions as the laws and organizations, including informal norms that organize human actions. Tvaronavičienė et al. (2008) argue that the concept of institution is much broader than the concept of organization and institutions. In a broad sense, the idea of institutions supports organizations. At the same time, the North approach can be followed in a narrow sense, implying that if institutions are the rules of the game, the players are organizations and their entrepreneurs (North, 1994).

Some levels of institutions were defined by Williamson (2000), level one deals with the highest level of the institutional hierarchy and it provides the fundamental foundations for the institutions in a society. Informal structures, practices, beliefs, ethics and social values, faith, and some elements of language and cognition are included. While level two on the other hand belongs to the primary institutional setting or the structured game rules. Political structures and fundamental human rights are defined at this level; property rights and their allocation; rules, courts, and related institutions for the enforcement of political, human rights and property rights; money, primarily financial institutions and the powers of government to tax; laws and institutions regulating migration, trade, and foreign investment laws; and political, legal and economic laws.

Many researchers who assert the primary importance of institutions have disagreements about the range of questions, such as whether it is appropriate to differentiate political and economic institutions, whether institutions and organizations are synonymous, etc. Besides, the root of an institution is also another point of contention as to whether it is endogenous or exogenous (Aoki, 2001; Gwartney et al., 2006; Helliwell, 1994). Moreover, even admitting these interpretative pitfalls, we still need to pick metrics that represent the institutional state by taking institutional development feedback into account at the level of aggregate sustainable development achieved.

Institutional Quality and Green GDP (GGDP) Linked

Some studies have looked into the impact of governance on a country's environmental performance and socioeconomic advancement. Raju et al. (2020) used data from South Asian countries to investigate the impact of governance on economic development and noticed that governance affects development positively. A similar outcome was also observed in the study of Abdelbary and Benhin (2019). The latter also utilized data from Arab countries to assess governance roles in human capital and GDP advancement. According to their findings, good governance positively impacts these two variables in the Arab nations. Besides, the study of Samarasinghe (2018) also uses corruption control as a proxy for governance and discovered that lower corruption rates significantly induce GDP expansion.

Some studies also found out that the level of effectiveness of governance has important effects on environmental matters. In this regard, Bernauer and Koubi (2009) noted that any country's government can organize proper drivers to improve environmental performance. Similarly, Wang et al. (2009) show that increased government effectiveness leads to increased environmental quality improvement when governance is targeted at realizing long-run GDP growth. In another study, Moshiri and Hayati (2017) examined the ways the level of governance effectiveness affects how the environment fairs in about 149 countries, and they discovered that governance has a direct effect on the environment. In another study by Bernauer and Koubi (2009), the impacts of political systems on air quality were scrutinized and the study's findings suggest that democracy positively impacts air quality.

Li et al. (2018) conducted research on the relationship between governance quality and environmental sustainability in China. Their findings indicated that improved governance quality positively influenced environmental sustainability, emphasizing the importance of effective governance in achieving green development. Another relevant study by Carney et al. (2019) focused on the role of governance in promoting sustainable economic growth and reducing environmental degradation in Sub-Saharan Africa. The research highlighted the need for good governance practices to drive sustainable development and emphasized the potential for green GDP measures to guide policy decisions towards more environmentally friendly outcomes. Additionally, a study by Song et al. (2020) investigated the impact of governance quality on green economic growth in Asian countries. The results revealed that higher governance quality positively correlated with increased green economic growth, emphasizing the significance of effective governance in driving sustainable economic development. In a different study, Rahman et al. (2021) examined the relationship between governance quality, economic growth, and environmental sustainability in developing countries. The study highlighted the crucial role of good governance in promoting both economic growth and environmental sustainability, emphasizing the potential benefits of incorporating green GDP measures into policy frameworks.

Furthermore, Ahmed et al. (2021) considered data from different nations based on income groups while investigating the governance-environment nexus from the climate change perspective. CO2 emissions are used in the study to assess the dynamics of climate change and the outcomes show substantial roles of governance in influencing climate change, thus concluding that strong governance helps improve environmental quality. According to the study, the global community must provide significant economic and financial help to developing countries to strengthen their environmental and institutional capacities.

After reviewing the existing literature, it is evident that a considerable body of research has explored the relationship between governance, economic growth, and environmental sustainability. However, one notable gap in the literature is the limited attention given to the link between institutional quality and green gross domestic product (green GDP). While studies have examined the influence of governance on economic development and environmental performance separately, there is a lack of research specifically investigating the connection between institutional quality and green GDP. This research aims to fill this gap by examining the relationship between institutional quality and green GDP using appropriate green GDP metrics and comprehensive measures of institutional quality. By addressing this research gap, the study will contribute to a deeper understanding of how institutional quality can shape the development of sustainable and environmentally friendly economies.

Theoretical Framework, Data, Model Specification & Methodology

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework of this study draws on the concept of institutional quality and its influence on green gross domestic product (green GDP). Institutional quality refers to the effectiveness, efficiency, and transparency of institutions within a country, including governance structures, policies, and regulations (North, 1990). The theoretical foundation of this study is rooted in the understanding that institutions play a crucial role in shaping economic development and environmental outcomes. The study adopts the framework of the Institutional Theory, which posits that institutions are social constructs that guide human behavior and shape economic and environmental outcomes. According to this theory, the quality of institutions influences the behavior of individuals, organizations, and governments, which in turn affects economic performance and environmental sustainability.

Within the context of this study, the Institutional Theory provides a lens to examine how institutional quality can influence the development and implementation of green GDP policies and practices. It helps to explore the mechanisms through which institutional factors, such as governance structures, corruption control, and policy effectiveness, interact with economic and environmental variables to shape green GDP outcomes. Additionally, the study incorporates elements of the Sustainable Development Theory, which emphasizes the integration of economic, social, and environmental dimensions for long-term sustainable development. By incorporating this theory, the study recognizes the importance of balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability and social well-being.

By employing the Institutional Theory and Sustainable Development Theory, this study aims to provide a theoretical understanding of the relationship between institutional quality and green GDP. It seeks to uncover the mechanisms through which institutional factors influence green GDP outcomes and identify the key institutional dimensions that contribute to sustainable and environmentally friendly economic growth. Overall, the theoretical framework of this study provides a foundation for analyzing the complex interactions between institutions, economic development, and environmental sustainability within the context of green GDP.

Data and Model Specification

The study investigates the effects of institutional quality on green GDP in Sub Sahara African (SSA) nations. These nations were chosen for the study based on the availability of data. We used data from the World Bank from 1996 to 2018 for the study. Institutional quality measures were used as independent factors to explain their roles in Green GDP advancement while other factors like industrialization, energy use, and population growth were incorporated as control variables. To realize long-term green GDP, it is crucial to understand the cumulative effect of each aspect of institutional quality. There is no general agreement on how to estimate green GDP and there is even little consensus on whether or not to embark on its estimations (Böhringer & Jochem, 2007). However, we utilized a general estimation scheme as follows: Green GDP = GDP – (CO2 emissions in kt *total CDM in average prices for kt) – (t of waste*74kWh of electrical energy x price for 1kWh of electrical energy) – (G.N.I./100 × natural resources depletion % of GNI). This scheme can be expressed as seen in Eq. (1):

The first deduction in Eq. (1) represents CO2 pollution costs (as CO2 emissions times carbon market price), the second represents the opportunity costs of one tonne of waste that could be used in the development of electrical energy, and the third represents the modified savings of natural resource depletion as a percentage of gross national income per country. The study adopted the Green GDP metrics and embedded them with a simplified Solow growth model as developed in Eq. (2):

where GGDP is Green GDP, IQ on the other hand is the institutional quality, and Z is the control variable. The factors above were integrated into the study to create the model (3), which was used to estimate the connection.

The World Bank provided data for all variables from 1996 through 2018. In Eq. (3) GGDP means green GDP, IQ stands for institutional quality measured with six indicators namely Corruption Control (COC), Government Effectiveness (GE), Political Stability (PS), Regulatory Quality (RQ), Rule of Law (ROL), Voice of Accountability (VA). As for industrialization (percentage), it is denoted by IND while ENE stands for energy usage (kg), and POP stands for population growth (Percentage). The descriptive and correlation statistics for the variables are shown in Table 1. The subscript t denotes the time-series nature of the data, the cross-sections are denoted by the subscript I, the intercept is denoted by the subscript s, and the numbers δ1, δ2,….δ5 denotes the variables' unknown parameters, which must be estimated.

The results of the overview of the variables, their correlations, and their statistical characteristics show that industrialization has the most excellent mean score of variables (29.8364), while government effectiveness is low (-0.3236). According to the findings, the other institutional quality indicators all had negative means, while the control variables had positive means. Table 1 also contains the results of the pair-wise relations. The study discovers a favorable relationship between green GDP and indices of institutional quality. Green GDP and population have a negative association, with industrialization and energy being positively linked to green GDP. All of the factors have a negative association with the population.

Econometric Techniques

To reach the study’s aims and objectives, the researchers used various econometric techniques, including cross-sectional dependency, to analyze sectional attributes and slope homogeneity testing to investigate the presence of heterogeneity throughout the sequence. The bootstrap quantile regression was used to determine the long-term effects, Westerlund's (2007) cointegration test was used, and the Dumitrescu and Hurlin's (2012) causality test to deal with long-term causation.

Cross-Sectional Dependence & Slope Homogeneity Tests

Some recent studies have emphasized the importance of examining cross-sectional dependence in panel variables (Baltagi & Hashem Pesaran, 2007; Gyamfi et al., 2021; Onifade, 2023). Assuming that the observations in the cross-sections in our panel are not obtained independently such that they interfere with each other's results, the unwanted matter of cross-sectional dependence and homogeneity would be the resultant problem. This is because, due to regional integration and international trade, shocks can be readily transferred among nations (Appiah et al., 2021; Gyamfi, Onifade et al., 2023; Onifade & Alola, 2022). As a result, the study employs the likelihood of cross-sectional dependence tests of (Breusch & Pagan, 1980; Pesaran, 2015). Swamy (1970) also presents a rationale for the assumption of homoscedasticity for the panels where N is chosen relative to T while measuring slope homogeneity. The application of cross-sectional dependence and slope homogeneity tests enhances the robustness of the analysis and provides a more accurate understanding of the relationships between the variables under investigation. These techniques help to mitigate potential biases arising from cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity, enabling more reliable and meaningful conclusions to be drawn from the panel data analysis.

Panel Unit Root Tests

The test is used to establish whether or not panel data is stationary. "First-generation unit-root tests" and "second-generation unit-root tests" are the two types of panel unit-root testing. The stationarity of the data is checked using first-generation unit-root tests, which are based on the crucial assumption of individual cross-sectional independence. Second-generation unit-root tests, on the other hand, examine the data's stationarity while accounting for the problem of individual cross-sectional dependency. As a result, the findings of cross-sectional dependence tests are used to select panel unit-root tests. Pesaran's (2015) test was used to find cross-sectional dependence among the variables in this study as a better alternative to Breusch and Pagan (1980). On the other hand, we utilize the cross-sectional Im-Pesaran-Shin (CIPS) and cross-sectional Im-Pesaran-Shin augmented dickey fuller (CADF) tests to check the data's stationarity. By employing both cross-sectional dependence tests and panel unit-root tests, this study ensures a comprehensive assessment of the stationarity properties of the panel data. The use of Pesaran's test for cross-sectional dependence and the CIPS and CADF tests for data stationarity enhances the accuracy and reliability of the analysis, providing valuable insights into the dynamics of the variables under investigation.

Cointegration Tests

The long-run relationship between the variables is investigated using Westerlund's (2007) cointegration tests. The Westerlund (2007) cointegration test based on error correction was applied because the current data is cross-sectionally dependent. Four tests (Ga, Gt, Pa, and Pt) were used in the Westerlund cointegration including two panel-specific tests and two group-specific tests. The null in panel test explains that there is co-integration across the board. In contrast, the group-specific tests show that rejecting the null in group test explains cointegration across at least one group in the panels. The utilization of Westerlund's (2007) cointegration tests offers several benefits in examining the long-run relationship between variables. First, these tests account for the presence of cross-sectional dependence, which is crucial in panel data analysis. By considering cross-sectional dependence, the co-integration tests provide more accurate and reliable results. Second, the inclusion of both panel-specific and group-specific tests allows for a comprehensive assessment of cointegration across the entire panel and within specific groups. This enables the identification of common long-run relationships across all groups as well as specific relationships within individual groups. Overall, the application of Westerlund's cointegration tests enhances the robustness and depth of analysis in determining the existence of long-run relationships among the variables.

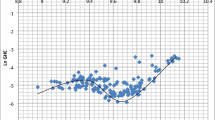

Quantile Regression Method

To explore the impact of institutional quality on green GDP, the panel quantile regression model is used to analyze the long-run impacts. The conditional distribution in nations for the research variables association is investigated using panel quantile regression. Because traditional regression techniques focus on mean effects, they may lead to over or underestimation of relevant coefficients, or they may fail to discover an important association (Binder & Coad, 2011). When there are outliers and the dependent variable's distribution is highly non-normal, the QR estimate approach is more resilient than the OLS approach (Okada & Samreth, 2012; Onifade et al., 2023). Quantile regression is more resilient in heavy distributions, but it can't deal with unobserved national heterogeneity. The utilization of panel quantile regression in this study offers several benefits. Firstly, it allows for the exploration of the impact of institutional quality on green GDP by examining the conditional distribution of the research variables association across nations. This approach goes beyond traditional regression techniques that focus on mean effects and enables a more comprehensive analysis of the relationship. Secondly, panel quantile regression is particularly resilient in the presence of outliers and when the distribution of the dependent variable deviates significantly from normality. This robustness makes it suitable for capturing the effects of extreme values and non-normal distributions, which may be present in the data. Lastly, by employing panel quantile regression, the study considers both conditional heterogeneity and unobserved individual heterogeneity, thereby providing a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between institutional quality and green GDP. As a result, the current study used a panel quantile to look at conditional heterogeneity as well as unobserved individual heterogeneity (Khan et al., 2020). Equation (4) is an example of how median regression analysis can be used to various quantiles:

In Eq. (4), Q represents the random conditional quantile in a way that the τth conditional quantile of the dependent Y given X is the τth quantile of the probability distribution (conditional) of the dependent Y given independent variable X.

Empirical Results

To determine the relationship between institutions and the achievement of green GDP, we examined how the data's cross-sections and slope homogeneity are interdependent as the initial step in the analytical procedure. We employed the CD (Pesaran, 2015), cross-section dependence tests, as well as the slope homogeneity tests and CDadj Pesaran et al. (2008), slope homogeneity tests (Pesaran & Yamagata, 2008). The tests revealed cross-sectional dependence and slope homogeneity in the data, as shown in Table 2. Thus, the applicability of the second-generation unit root test is established. Then, we assess the order of integration of the variables by confirming their stationarity properties before estimating the long-run coefficients. We used CIPS and (CADF) tests to do this (Pesaran, 2007). Except for GGDP, PS, and POP, all model parameters found to have the unit root at the level were stationary at the first difference for both tests (see Table 3). As a result, the variables can be concluded to be integrated at I(0) and I(1), justifying the use of the cointegration test. We can now proceed with validating the long-run connection after finding evidence for the model parameters' integrating property.

We used the panel cointegration test Westerlund (2007) to determine the occurrence of cointegration. The null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected, confirming cointegration between the variables for the sub-Saharan region. This reaffirms the validity and reliability of empirical findings. Table 4 shows the results of the Westerlund cointegration test. We can proceed to calculate the long-run coefficients of the model parameters based on this piece of information.

Quantile Regression Results of Institutional Quality Variables

The effect of institutional quality on Green GDP was estimated using quantile regression as seen in Table 5. We examined the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th quantile points and the symmetrical distribution of these quantile points is helpful for the empirical investigation. The estimated results of the classic panel data model using ordinary least squares (OLS) are also presented in this study. The institutional quality quantile regression results elicited a mixed response. The result shows positive and significant relationships between control of corruption (COC) and Green GDP at the initial stage (0.10th and 0.25th quantiles) and non-significant at the 50th quantile. This denotes that the measures of corruption control in sub-Sahara African countries impact the region's achievements of Green GDP favorably at the initial stage. The output of OLS and other quantiles (0.75th and 0.90th) all show a positive relationship. This is supposed to be the dominant impact of corruption control, considering that both median (0.50th) and OLS depict the same significant finding. Appiah et al. (2019) studied the effect of controlling corruption on growth and found that controlling corruption has a positive impact on growth. Thus, the finding supports some extant empirical conclusions. Besides, the proof of corruption adversely impacting biodiversity and negatively affecting sustainable growth has been found in some other papers (Damania et al., 2004; Lopez & Mitra, 2000; Meyer et al., 2003).

Again, the effect of government effectiveness (GE) on achieving Green GDP from the quantile regression estimates shows statistically significant positive relations from 25 to 75th quantiles. The results of the 90th quantile show a positive and insignificant regression outcome, with the OLS outputs indicating a positive and a significant relationship. In contrast, at the 10th quantile, the effect is negative and insignificant. This result validates the effectiveness of government policies in achieving Green GDP in SSA countries. If government output is continuously improving to such an extent that green GDP improves, it is said that green GDP has increased. Nevertheless, it also reflects the essence of the policies adopted by the government. To achieve economic development, most governments adopt social action programs to help boost green GDP achievement. According to Dasgupta and De Cian (2016), more robust governance generally leads to greater implementation of sustainable growth and performance.

The effect of regulatory quality (RQ) captured by the regression posits a significant and a positive nexus right from the OLS outputs straight and through from the 10th to the 50th quantile. This result proves that strict adherence to regulations leads to the achievement of Green GDP in SSA countries. The results show that regulatory quality was influential in the initial years through to the middle years but later became ineffective in the last years. This result implies that SSA countries before and to the median exhibit greater regulation adherence but become reluctant. This may stem from the different changes of regulations and practices obtainable from the government and administrations. Research based on two different estimation methods involving developing countries by Jalilian et al. (2007) indicates a clear causal correlation between regulatory quality and growth and this result is consistent with the research.

The results yielded a mixed bag of estimations and relationships on political stability. Political stability (PS) negatively affects green GDP in Sub-Sahara African countries at the 10th and 25th quantiles, considerably impacting the 10th. From the 50th to the 90th quantiles, the link between these two variables becomes positive and significant. This indicates that PS positively impacts the region’s Green GDP attainment later on. The OLS output reveals a positive but negligible correlation. In the model situation, it is assumed that the institutional efficiency components of growth are emphasized. As a result, when estimating the degree of green GDP, metrics of political stability are thought to be more relevant and favorable. The BQR method shows that the degree of political stability in SSA aids in achieving the highest level of green GDP between the 50th and 90th quantile levels of estimation. According to the absence of political turbulence and improved SSA stability, the green GDP improves. Green GDP is usually accomplished under fair and favorable political conditions.

The result remained positive and insignificant in the OLS regressions, with a negative and insignificant affirmation in the 10th quantile and median. For the 25th, 75th, and 90th quantiles in Africa’s Sub-Saharan regions, there is a positive but minor association between rule of law (ROL) and Green GDP. This insignificant nature of the results does not prove any strength on the claim that ROL in Sub-Saharan Africa is aimed toward green GDP. After accomplishing their economic goals, most emerging countries including the SS African countries, are only considering the concept of green GDP by believing in the laid down rules and regulations. Although rule of law was not significant to green growth in the case of SSA, the result from Barrett and Graddy (2000) confirms that rule of law can promote growth.

The results and estimates indicate that the impact of voice and accountability (VA) on the Green GDP index is similar across all quantiles. In addition, the results also vary in the coefficients, with the lowest being -1.2540 for the 25th quantile and highest for the 90th quantile with the value -0.5208. The results across all quantiles validate the results of the OLS. Compared to previous assumptions, the impact of voice and accountability remains that more excellent voice and accountability contribute to higher stress on sustainable growth. VA is associated with the dependent variable. Voice and accountability have a robust negative effect on GGDP, where the coefficient shows that the dependent variable changes 1 unit when VA changes one unit (which is minimal for an index ranging from 0 to 5).

Looking at the control variables, the results based on energy utilization showed that its effect on Green GDP is positive and statistically significant in all the quantiles in SSA countries (i.e. 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th quantiles). This finding could be attributed to the introduction and usage of renewable energy by industries. If this is the case, it is expected that the impacts of industrialization on Green GDP would be positive, and this was the case based on the results. Besides, the impacts of the two variables (energy utilization and industrialization) are highly significant in all quantiles, suggesting that SSA countries are advancing towards the use of modern technologies for production with more renewable energy. On the other hand, the relationship between population growth and green GDP is negative and insignificant across all quantiles and the OLS estimates for the SSA countries. It notably indicates that from the 10th quantile, the impact of population growth on green GDP continues to reduce as per the coefficients to the 90th quantile. This phenomenon also exists in many provinces in the case of China (Li & Lang, 2010).

In this work, the DH causality test was used to examine and validate findings from other analyses such as quantile regression and OLS estimations. The causality estimation further assists in emphasizing the importance of institutions in achieving GGDP. The analysis establishes the movement and origin of the effect and shows the direction of the relationship that existed among the variables. Table 6 shows the results of the causality evaluation. The findings confirmed a single-track causal relationship between GGDP, government effectiveness, political stability, regulatory quality, energy consumption, and population increase. There are four examples showing a link between government efficiency, political stability, energy use, population, and GGDP. Finally, there was double-track causation between GGDP and VA in SSA countries. This further stresses the role of the various institutional quality measures that are adopted in understanding green GDP in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

This study provides an understanding of the institutional quality-green GDP nexus by utilizing broad measures of institutional quality while controlling for industrialization, energy use, and population growth. This research uses a panel quantile regression approach and a balanced annual panel data model to examine the numerous impacts of institutional quality on green GDP in SSA countries from 1996 to 2018. The empirical studies in this research show that despite its significant contribution to environmental deterioration, industrialization, and energy use in SSA nations surprisingly promotes a higher level of green GDP, unlike population growth that hurt green GDP in the SSA.

Furthermore, in SSA nations, the voice of accountability performs poorly in supporting green GDP. Meanwhile, the correlations between the rule of law (ROL) and green GDP appear to vary depending on the extent of the ROL index increase. For example, in SSA nations, ROL has a more significant rebound impact in the 75th and 90th quantiles. Furthermore, the amount to which regulatory quality can increase green GDP in SSA nations varies. Green GDP increases in the early stages, decreases in the middle stages, and decreases in the last two stages. Regarding political stability in SSA countries, it hurts green GDP in the 10th quantile but improves from the median to the 90th quantile. However, in terms of government effectiveness in SSA countries, green GDP can only be improved in the 25th, 50th, and 75th quantiles. There was an increase in green GDP with the influence of corruption control at the first two and fourth quantiles, including the OLS results, but it became insignificant at the median and 90th quantiles. For SSA and other developing economies aiming for green GDP, these findings provide new insights and policy implications.

Based on the findings of the study, there are several policy recommendations that can be made to policymakers in the investigated bloc, specifically the SSA countries, to promote green GDP and sustainable development:

Firstly, there is a need to enhance the rule of law. Policymakers should prioritize efforts to improve the rule of law and strengthen the legal environment. This includes refining the legal system, increasing the efficiency of laws and regulations, and ensuring strict enforcement. By creating a robust legal framework, policymakers can provide a stable and predictable environment that encourages green investment and innovation. There is also a need to promote regulatory quality. Policy makers should focus on enhancing regulatory quality, ensuring that regulations are effective, efficient, and supportive of green economic activities. They should strive for consistency and coherence in regulations and ensure that they facilitate sustainable practices and technologies. Regular evaluation and monitoring of regulatory frameworks can help identify areas for improvement and encourage continuous progress in promoting green GDP.

Additionally, adequate emphasis and attention should be paid to issues bordering on political stability. Policymakers should work towards maintaining political stability in SSA countries. This involves fostering peaceful transitions of power, reducing political instability and conflicts, and creating a conducive environment for long-term sustainable development. Political stability provides the necessary foundation for attracting investments, promoting green initiatives, and ensuring policy continuity in achieving green GDP. Policymakers should also prioritize enhancing government effectiveness and efficiency in implementing policies related to green GDP. This includes improving governance structures, streamlining administrative processes, and enhancing coordination among different government agencies. By increasing the effectiveness of public institutions, policymakers can better address environmental challenges, promote green technologies, and ensure the effective implementation of sustainable development strategies.

Furthermore, public education and awareness should be promoted. Policymakers should prioritize public education and awareness campaigns to highlight the importance of achieving green GDP and sustainable development. By engaging and informing the public about the benefits of environmentally friendly practices, sustainable consumption, and renewable energy, policymakers can foster a culture of sustainability and encourage individual and collective actions toward green growth. While doing so, there is also a need to encourage international cooperation on sustainability frontiers. Policymakers should actively seek international cooperation and collaboration to address global environmental challenges. This includes participating in international agreements, sharing best practices, and accessing financial and technical assistance for sustainable development projects. By collaborating with other countries and international organizations, policymakers can leverage global expertise and resources to accelerate the transition toward green GDP.

Overall, these policy recommendations aim to create an enabling environment that supports green economic activities, encourages sustainable practices, and facilitates the transition towards green GDP in SSA countries. By implementing these policies, policy makers can promote long-term economic growth, environmental preservation, and social well-being.

Limitation of the Study and Future Recommendation

The limitations of the present study can be seen from two areas, firstly in terms of data, secondly in terms of generalization of results. In terms of data availability and quality, the study relied on existing data sources, which may have limitations in terms of coverage, accuracy, and consistency across countries. Improving data collection methods and establishing comprehensive databases specific to green GDP and institutional quality would enhance the robustness of future studies. Also, the study focused on exploring the associations between institutional quality and green GDP, but establishing causal relationships is challenging. However, endogeneity issues may arise due to unobserved variables or reverse causality. Future research could employ innovative methodologies, such as instrumental variable approaches or natural experiments, to address these challenges. Lastly, in terms of generalizability, the findings of this study are specific to the SSA countries and may not be directly applicable to other regions or country contexts. Replicating the analysis in different geographical areas would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the institutional quality-green GDP nexus.

Data Availability

The data for this present study are sourced from the database of the World Development Indicators (https://data.worldbank.org).

References

Abdelbary, I., & Benhin, J. (2019). Governance, capital and economic growth in the Arab Region. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 73, 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2018.04.007

Adams, S., Klobodu, E. K. M., & Apio, A. (2018). Renewable and non-renewable energy, regime type and economic growth. Renewable Energy, 125, 755–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.02.135

Adebayo, T. S., Gyamfi, B. A., Bekun, F. V., Agboola, M. O., & Altuntaş, M. (2023). Testing the mediating role of fiscal policy in the environmental degradation in Portugal: Evidence from multiple structural breaks co-integration test. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01351-4

Adedoyin, F. F., Bekun, F. V., Hossain, M. E., Kwame Ofori, E., Gyamfi, B. A., & Haseki, M. I. (2023). Glasgow climate change conference (COP26) and its implications in sub-Sahara Africa economies. Renewable Energy, 206, 214–222.

Ahmed, F., Kousar, S., Pervaiz, A., & Shabbir, A. (2021). Do institutional quality and financial development affect sustainable economic growth? Evidence from South Asian countries. Borsa Istanbul Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2021.03.005

Anyanwu, J. C. (2014). Factors affecting economic growth in Africa: Are there any lessons from China? African Development Review, 26(3), 468–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12105

Aoki, M. (2001). Toward a comparative institutional analysis. MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/toward-comparative-institutional-analysis

Ali, E. B., Gyamfi, B. A., Bekun, F. V., Ozturk, I., & Nketiah, P. (2023). An empirical assessment of the tripartite nexus between environmental pollution, economic growth, and agricultural production in Sub-Saharan African countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27307-4

Awosusi, A. A., Mata, M. N., Ahmed, Z., Coelho, M. F., Altuntaş, M., Martins, J. M., ... & Taiwo, S.O. (2022). How do renewable energy, economic growth and natural resources rent affect environmental sustainability in a globalized economy? Evidence from Colombia based on the gradual shift causality approach. Frontiers in Energy Research, 9, 739721. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2021.739721

Appiah, M., Li, F., & Korankye, B. (2021). Modeling the linkages among CO2 emission, energy consumption, and industrialization in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(29), 38506–38521.

Appiah, M., Frowne, D. I., & Frowne, A. I. (2019). Corruption and its effects on sustainable economic performance. International Journal of Business Policy & Governance, 6(2), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.19085/journal.sijbpg060201

Appiah, M., Li, M., Sehrish, S., & Abaji, E. E. (2023). Investigating the connections between innovation, natural resource extraction, and environmental pollution in OECD nations; Examining the role of capital formation. Resources Policy, 81, 103312.

Baltagi, B. H., & Hashem Pesaran, M. (2007). Heterogeneity and cross section dependence in panel data models: Theory and applications introduction. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22(2), 229–232.

Barrett, S., & Graddy, K. (2000). Freedom, growth, and the environment. Environment and Development Economics, 5(4), 433–456. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X00000267

Bekun, F. V., Gyamfi, B. A., Köksal, C., & Taha, A. (2023). Impact of financial development, trade flows, and institution on environmental sustainability in emerging markets. Energy & Environment. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958305X221147603

Bekun, F. V., Gyamfi, B. A., Onifade, S. T., & Agboola, M. O. (2021). Beyond the environmental kuznets curve in E7 economies: Accounting for the combined impacts of institutional quality and renewables. Journal of Cleaner Production, 314, 127924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127924

Bernauer, T., & Koubi, V. (2009). Effects of political institutions on air quality. Ecological Economics, 68(5), 1355–1365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.09.003

Binder, M., & Coad, A. (2011). From average Joe’s happiness to miserable Jane and Cheerful John: Using quantile regressions to analyze the full subjective well-being distribution. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 79(3), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2011.02.005

Breusch, T. S., & Pagan, A. R. (1980). The Lagrange multiplier test and its applications to model specification in econometrics. The Review of Economic Studies, 47(1), 239–253.

Böhringer, C., & Jochem, P. E. (2007). Measuring the immeasurable—A survey of sustainability indices. Ecological Economics, 63(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.03.008

Carney, L., Ngoasong, M. Z., & Ram, M. (2019). Governance, economic growth and environmental sustainability in Sub-Saharan Africa: Comparative analysis of institutions and green sectors. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(4), 660–673.

Château, J., Rebolledo, C. & Dellink, R. (2011). An economic projection to 2050: The OECD "ENV-Linkages" Model Baseline". OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 41, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5kg0ndkjvfhf-en.

Chan, H. K., Yee, R. W., Dai, J., & Lim, M. K. (2016). The moderating effect of environmental dynamism on green product innovation and performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 181, 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.12.006

Çevik, S., Erdoğan, S., Taiwo, S. O., Asongu, S., & Bekun, F. V. (2020). An empirical retrospect of the impacts of government expenditures on economic growth: New evidence from the Nigerian economy. Journal of Economic Structures, 9(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-020-0186-7

Cubbage, F., Diaz, D., Yapura, P., & Dube, F. (2010). Impacts of forest management certification in Argentina and Chile. Forest Policy and Economics, 12(7), 497–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2010.06.004

Çoban, O., Onifade, S. T., Yussif, A. R. B., & Haouas, I. (2020). Reconsidering trade and investment-led growth hypothesis: new evidence from Nigerian economy. Journal of International Students, 13(3), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2020/13-3/7

Damania, R., Fredriksson, P. G., & Mani, M. (2004). The persistence of corruption and regulatory compliance failures: Theory and evidence. Public Choice, 121(3), 363–390.

Dasgupta, S., & De Cian, E. (2016). Institutions and the environment: Existing evidence and future directions. https://www.feem.it/en/

Donelli, F., & Chiriatti, A. (2017). Turkish civilian capacity in post-conflict scenarios: The cases of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. Journal of Global Analysis, 7(1). https://eds.s.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=97719362-5642-4933-9b0d-bbe9a68d5ea8%40redis

Dumitrescu, E. I., & Hurlin, C. (2012). Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Economic Modelling, 29(4), 1450–1460.

Erdoğan, S., Taiwo, S. O., Alagöz, M., & Bekun, F. V. (2021). Renewables as a pathway to environmental sustainability targets in the era of trade liberalization: Empirical evidence from Turkey and the Caspian countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(31), 41663–41674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13684-1

Erdoğan, S., Stephen, O. T., & Alola, A. A. (2023). The role of alternative energy and globalization in decarbonization prospects of the oil-producing African economies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(1), 58128–58141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-26581-6

Gan, Y., & Griffin, W. M. (2018). Analysis of life-cycle GHG emissions for iron ore mining and processing in China—uncertainty and trends. Resources Policy, 58, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.03.015

Gwartney, J. D., Holcombe, R. G., & Lawson, R. A. (2006). Institutions and the impact of investment on growth. Kyklos, 59(2), 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2006.00327.x

Gyamfi, B. A., Onifade, S. T., Nwani, C., & Bekun, F. V. (2021). Accounting for the combined impacts of natural resources rent, income level, and energy consumption on environmental quality of G7 economies: a panel quantile regression approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15756-8

Gyamfi, B. A., Agozie, D. Q., Bekun, F. V., & Köksal, C. (2023). Beyond the Environmental Kuznets Curve in South Asian economies: accounting for the combined effect of information and communication technology, human development and urbanization. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03281-2

Gyamfi, B. A., Onifade, S. T., Erdoğan, S., & Ali, E. B. (2023). Colligating ecological footprint and economic globalization after COP21: Insights from agricultural value-added and natural resources rents in the E7 economies. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 30(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2023.2166141

Helliwell, J. F. (1994). Empirical linkages between democracy and economic growth. British Journal of Political Science, 24(2), 225–248. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400009790

Hodgson, G. M. (2006). What are institutions? Journal of Economic Issues, 40(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2006.11506879

Haouas, I., Taiwo, S. O., Gyamfi, B. A., & Bekun, F. V. (2021). Re-examining the roles of economic globalization and natural resources consequences on environmental degradation in E7 economies: Are human capital and urbanization essential components? Resources Policy, 74, 102435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102435

Jalilian, H., Kirkpatrick, C., & Parker, D. (2007). The impact of regulation on economic growth in developing countries: A cross-country analysis. World Development, 35(1), 87–103.

Khan, H., Khan, I., & Binh, T. T. (2020). The heterogeneity of renewable energy consumption, carbon emission and financial development in the globe: A panel quantile regression approach. Energy Reports, 6, 859–867.

Kim, B., Kyophilavong, P., Nozaki, K., & Charoenrat, T. (2020). Does the export-led growth hypothesis hold for Myanmar?. Global Business Review, 23(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0972150919863929

Liu, M. H., Margaritis, D., & Zhang, Y. (2019). The global financial crisis and the export-led economic growth in China. The Chinese Economy, 52(3), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2018.1548144

Li, V., & Lang, G. (2010). China’s “Green GDP” experiment and the struggle for ecological modernisation. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 40(1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472330903270346

Li, M., Shi, M., & Zhong, L. (2018). Governance quality and environmental sustainability: Evidence from China. Sustainability, 10(10), 3525.

Lopez, R., & Mitra, S. (2000). Corruption, pollution, and the Kuznets environment curve. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 40(2), 137–150.

Mäler, K. G., Aniyar, S., & Jansson, Å. (2008). Accounting for ecosystem services as a way to understand the requirements for sustainable development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(28), 9501–9506. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708856105

Mardones, C., & del Rio, R. (2019). Correction of Chilean GDP for natural capital depreciation and environmental degradation caused by copper mining. Resources Policy, 60, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.12.010

McMillan, M., Rodrik, D., Bacchetta, M., & Jensen, M. (2011). Making globalization socially sustainable. In Bacchetta M, Jansen M (Ed.), Chapter globalization, structural change, and productivity growth. International Labour Organization and World Trade Organization. https://www.wto.org/English/res_e/publications_e/ilo_wto_e/ILO-WTO02-final.pdf

McIntosh, S., & Renard, Y. (2009). Placing the commons at the heart of community development: three case studies of community enterprise in Caribbean Islands. International Journal of the Commons, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.135

Meyer, A. L., Van Kooten, G. C., & Wang, S. (2003). Institutional, social and economic roots of deforestation: A cross-country comparison. International Forestry Review, 5(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1505/IFOR.5.1.29.17427

Moshiri, S., & Hayati, S. (2017). Natural resources, institutions quality, and economic growth; A cross-country analysis. Iranian Economic Review, 21(3), 661–693. https://doi.org/10.22059/ier.2017.62945

Musah, M., Gyamfi, B. A., Kwakwa, P. A., & Agozie, D. Q. (2023). Realizing the 2050 Paris climate agreement in West Africa: The role of financial inclusion and green investments. Journal of Environmental Management, 340, 117911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117911

Nwaka, I. D., & Onifade, S. T. (2015). Government size, openness and income risk nexus: New evidence from some African countries (No. WP/15/056). AGDI Working Paper. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/149917

North, D. C. (1994). Economic performance through time. The American Economic Review, 84(3), 359–368. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118057

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112.

Onifade, S. T. (2022). Retrospecting on resource abundance in leading oil-producing african countries: How valid is the environmental kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis in a sectoral composition framework? environmental science and pollution research. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(1), 52761–52774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-19575-3

Onifade, S. T., & Alola, A. A. (2022). Energy transition and environmental quality prospects in leading emerging economies: The role of environmental-related technological innovation. Sustainable Development, 30(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2346

Ofori, E. K., Li, J., Gyamfi, B. A., Opoku-Mensah, E., & Zhang, J. (2023). Green industrial transition: Leveraging environmental innovation and environmental tax to achieve carbon neutrality. Expanding on STRIPAT model. Journal of Environmental Management, 343, 118121.

Onifade, S. T. (2023). Environmental impacts of energy indicators on ecological footprints of oil-exporting African countries: Perspectives on fossil resources abundance amidst sustainable development quests. Resources Policy, 82, 103481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.103481

Onifade, S. T., Haouas, I., & Alola, A. A. (2023). Do natural resources and economic components exhibit differential quantile environmental effect? Natural Resources Forum, 47(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12289

Okada, K., & Samreth, S. (2012). The effect of foreign aid on corruption: A quantile regression approach. Economics Letters, 115(2), 240–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2011.12.051

Pesaran, M. H. (2007). A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. Journal of applied econometrics, 22(2), 265–312.

Pesaran, M. H., Ullah, A., & Yamagata, T. (2008). A bias-adjusted LM test of error cross-section independence. The Econometrics Journal, 11(1), 105–127.

Pesaran, M. H., & Yamagata, T. (2008). Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. Journal of Econometrics, 142(1), 50–93.

Pesaran, M. H. (2015). Testing weak cross-sectional dependence in large panels. Econometric Reviews, 34(6–10), 1089–1117. https://doi.org/10.1080/07474938.2014.956623

Rahman, M. M., Chowdhury, A. H., & Osman, M. S. (2021). Governance quality, economic growth, and environmental sustainability in developing countries. Sustainability, 13(3), 1232.

Raju, A. S., Balasubramaniam, N., & Srinivasan, R. (2020). Governance evolution and impact on economic growth: A south Asian perspective. In Open government: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (pp. 2111–2139). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-9860-2.ch097

Samarasinghe, T. (2018). Impact of governance on economic growth. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/89834

Salman, M., Long, X., Dauda, L., & Mensah, C. N. (2019). The impact of institutional quality on economic growth and carbon emissions: Evidence from Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand. Journal of Cleaner Production, 241, 118331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118331

Sarpong, K. A., Xu, W., Gyamfi, B. A., & Ofori, E. K. (2023). A step towards carbon neutrality in E7: The role of environmental taxes, structural change, and green energy. Journal of Environmental Management, 337, 117556.

Song, X., Zhou, Y., & Jia, W. (2019). How do economic openness and R&D investment affect green economic growth?—evidence from China. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 146, 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.050

Song, M., An, S., Zhang, D., & Song, L. (2020). Governance quality and green economic growth: Evidence from asian countries. Sustainability, 12(14), 5577.

Swamy, P. A. (1970). Efficient inference in a random coefficient regression model. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 311–323. 1913012

Tajuddin, A. (2018). Upaya pengamanan energi Korea selatan melalui kebijakan green growth pada tahun 2009–2013. Universitas Brawijaya. http://repository.ub.ac.id/id/eprint/13142

Tvaronavičienė, M., Ginevičius, R., & Grybaitė, V. (2008). Comparison of Baltic Countries' development: practical aspects of complex approach. Business: Theory and Practice, 9(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.3846/1648-0627.2008.9.51-64

Vaghefi, N., Siwar, C., & Aziz, S. A. A. G. (2015). Green GDP and sustainable development in Malaysia. Current World Environment, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.12944/CWE.10.1.01

Wang, Z., Jia, H., Xu, T., & Xu, C. (2018). Manufacturing industrial structure and pollutant emission: An empirical study of China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 197, 462–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.092

Wang, X. (2011). Green GDP and openness: Evidence from Chinese provincial comparable green GDP. Journal of Cambridge Studies, 6(1), 1–16. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/255471/201101-article1.pdf?sequence=1

Wang, J., Mendelsohn, R., Dinar, A., Huang, J., Rozelle, S., & Zhang, L. (2009). The impact of climate change on China’s agriculture. Agricultural Economics, 40(3), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2009.00379.x

Westerlund, J. (2007). Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69(6), 709–748.

Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 595–613. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.3.595

Xu, L., Yu, B., & Yue, W. (2010). A method of green GDP accounting based on eco-service and a case study of Wuyishan, China. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 2, 1865–1872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2010.10.198

Xie, B. C., Duan, N., & Wang, Y. S. (2017). Environmental efficiency and abatement cost of China’s industrial sectors based on a three-stage data envelopment analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 153, 626–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.100

Yang, C., & Poon, J. P. (2009). Regional analysis of China’s green GDP. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 50(5), 547–563. https://doi.org/10.2747/1539-7216.50.5.547

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Vaasa. There is no specific funding received by the author for the study at the time of submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author (Michael Appiah) was responsible for the conceptual construction of the study’s idea. The second author (Stephen Taiwo Onifade) alongside the third author (Bright Akwasi Gyamfi) handled the introduction and literature sections. The data gathering, preliminary analysis, simulation, and interpretation of the simulated results were carried out by the first and third authors while proofreading and general manuscript editing were joint efforts of all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors wish to disclose here that there are no potential conflicts of interest at any level of this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Appiah, M., Onifade, S.T. & Gyamfi, B.A. Pathways to Sustainability in Sub-Sahara Africa: Are Institutional Quality Levels Subservient in Achieving Green GDP Growth?. J Knowl Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-01774-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-01774-7