Abstract

This paper explores the influence of the personality traits of dispositional optimism and risk orientation on Portuguese citizens’ preferences for lifestyle solidarity, on their lifestyle and the relationship between both personality traits. An online questionnaire was used to collect data from a sample of 584 Portuguese citizens. The quantitative analysis was performed through the Partial Least Square (PLS) model. The PLS explored the relationships between the constructs of dispositional optimism, risk preferences, own lifestyle and lifestyle solidarity. Linear regression analysis was also performed to identify the associations between respondents’ sociodemographic and economic characteristics and the above constructs. In general, respondents revealed high levels of lifestyle solidarity. Notwithstanding, we also found that: (i) while optimists and pessimists revealed less lifestyle solidarity, risk-prone revealed higher; (ii) while optimists were more prevention-orientation with their health behaviours, risk-seekers were less; (iii) more caregivers with their own lifestyles have less lifestyle solidarity, and (iv) while optimists were more risk-acceptant, pessimists were more risk-averse. This study presents the first evidence of how dispositional optimism and risk orientation affect the support of lifestyle solidarity and own lifestyles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Healthcare costs have grown faster than overall economic growth in developed countries. Across all the OECD countries, the annual health spending growth between 2000 and 2015 was 3.0%, compared to gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 2.3%, and it is estimated that this difference will remain in the future (OECD, 2019). Furthermore, it is projected that health expenditure as a share of GDP will rise from 8.2% in 2015 to 10.2% in 2030 (OECD, 2019). However, these estimates may be wrong by default, as the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disruptive healthcare systems. As a result, healthcare providers are now providing more non-COVID-19 care services (e.g. cancer treatments and elective surgeries), which will significantly inflate health costs. Thus, explicit measures dealing with the distribution of health resources need to be included in these countries’ political agendas. The rationing of healthcare is not new. Traditionally, elected officials shifted the burden of rationing decisions to health professionals to find a scapegoat for what they expected to be unpopular and difficult decisions (Garpenby & Nedlund, 2016). The current COVID-19 pandemic, which has increased the demand for public health resources to unprecedented levels, has forced medical professionals in some countries to decide which patients to assign life-saving equipment. The need to choose who to treat and who to let die became a pressing reality that frontline health professionals are not willing to burn alone anymore (Jüttemann & Wirth, 2021). In addition, the pandemic also had the adverse effect of conditioning economic growth through the deterioration of human capital (Chaabouni & Mbarek, 2023), compromising economic growth and thus exacerbating the scarcity of healthcare resources. However, this public health crisis had the merit of raising awareness among ordinary people of the shortage of health resources and the need to prioritize access to healthcare. This public health crisis is an opportunity to clearly define and implement explicit measures to allocate scarce healthcare resources.

In the past, health economists proposed using economic evaluation approaches to priority setting, grounded in maximising health benefits. Despite the merit of advancing the theoretical debate, there has been increasing interest in alternatives or extra dimensions with explicitly ethical origins (Williams, 1988). Several characteristics of people and their illnesses (see, e.g. Olsen et al., 2003; Dolan et al., 2005; Gu et al., 2015) have been investigated to determine to what extent the population and health professionals wish to account for such characteristics when setting health care priorities. The personal characteristics that have generated more controversy and raised increasing debate are whether people should be held responsible for their health-related behaviour when allocating scarce healthcare resources (see, e.g. Minkler, 1999; Cappelen & Norheim, 2005, 2006; Segall, 2009). The emphasis is on whether a healthcare claim is less legitimate if the individual contributed to their illness than if no such correlation is established. Several arguments have been put forward in favour of and against the idea of holding individuals responsible for their choices (for reviews, see, e.g. Cappelen & Norheim, 2005; Albertsen & Knight, 2015; Levy, 2018).

Along with this theoretical discussion, an increasing empirical literature has explored the support of the general public and health professionals (see e.g., Borges & Pinho, 2017; Pinho & Borges, 2019; Traina & Feiring, 2019) for using personal lifestyles as a criterion to prioritize patients. These studies rely on sociodemographic and health variables as drivers of social preferences. However, it has been recognized that an individuals’ response to an event is shaped by his sociodemographic characteristics and stable aspects of her personality (Borghans et al., 2008). Personality is an antecedent of personal values and lifestyles (Paetz, 2021). Since decisions related to patient prioritization involve ethical judgments, we believe that personality is a crucial variable in characterising social preferences. The role of personality traits in shaping how people think, feel and behave has long been recognized in psychology (Corr & Matthews, 2009). Suppose personality influences personal and social value judgments, i.e. evaluating certain behaviour as good or bad or as right or wrong. In that case, implications for health policy decision-making may be in order. However, the relationship between personality traits and healthcare rationing decision-making remains understudied.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only two studies have advanced in this matter by investigating the influence of dispositional optimism on preferences for allocating healthcare resources (Luyten et al., 2019; Pinho & Araújo, 2022). Luyten et al. (2019) explored the influence of dispositional optimism on how people set priorities in health using seven attributes, one of which was the link between disease and patients’ lifestyles. The authors found that more pessimistic individuals resorted less to patients’ age attributes when prioritizing them and revealed less predisposition to invest in prevention. Pinho and Araújo (2022) focused on the rationing criterion of patients’ lifestyles. The authors explored the influence of two personality traits—dispositional optimism and tolerance, on people’s support of using personal responsibility as a criterion to set healthcare priorities. They found that more optimistic individuals were supported using patients’ lifestyles as a selection criterion, while tolerant people were less responsive to accountability. Despite dispositional optimism and tolerance, the personality trait of risk orientation may also influence peoples’ healthcare priority-setting decisions. It is widely accepted that individuals’ risk orientation, i.e. their propensity to take risks or preference for specific or probabilistic outcomes (Ehrlich & Maestas, 2010), remains relatively stable throughout their life span (Nicholson et al., 2005). However, risk orientation influences public opinion and preferences for public programs, in general, and for health programs, in particular, remains to be studied. A recent study found that the support for welfare spending was rooted in the individuals’ perception of risk exposure conditional on their propensity to tolerate that risk (Milita et al., 2019). In the context of healthcare rationing decisions, the influence of the personality trait of risk orientation is unknown.

Given the potentially influential role that opinion plays in shaping policy, we must understand what shapes the publics’ desire for lifestyle solidarity—particularly in controversial policy matters such as rationing healthcare. To date, the role of simultaneously dispositional optimism and risk preferences in supporting the rationing criterion of lifestyle remains unstudied.

The present study aims to contribute to this literature by addressing some gaps. In the present study, we explore the effect of two personality traits—dispositional optimism and risk orientation, on Portuguese citizens’ preferences to support setting patients’ treatment priorities based on their lifestyle. We believe that whether someone generally expects to have a good or a bad future and is willing to take risks matters to fairness concerns and thus influences peoples’ views about the pertinence of using personal responsibility for the illness as a criterion for prioritizing patients. Furthermore, we explore the effect of dispositional optimism and risk preferences on individuals’ lifestyles. Finally, researchers mentioned that dispositional optimism might be entangled with other personality variables (Luyten et al., 2019). Thus, we also explore whether both personality traits are associated.

We used an online questionnaire to collect data from a sample of Portuguese citizens. We performed the relations between dispositional optimism, risk orientation, own lifestyle and lifestyle solidarity constructs by applying the partial least square (PLS) model. This quantitative approach has advantages over regressions, mainly the ability to handle more descriptor variables than compounds robustly and to provide more predictive accuracy and lower risk of chance correlations.

The paper is organized as follows. After the introduction, the literature review is presented. Then, the methodology used in the study is explained. The fourth section presents the study’s results, followed by a discussion. The paper concludes in the sixth section.

Theoretical Framework and Research Questions

Lifestyle Solidarity

Health systems comprise many forms of solidarity (Davies & Savulescu, 2019). An encompassing healthcare system entails solidarity, among others, between the sick and the healthy, the old and the young, employers, employees and the unemployed and between smokers and non-smokers, between teetotallers, moderate drinkers and alcoholics, between careful and reckless drivers, between the fat and skinny, etcetera. During the last 30 years, all these forms of solidarity have been questioned due to the unsustainability of the Welfare states. Raising private hospitals diminished the solidarity between the rich and the poor. Furthermore, population ageing makes us question what solidarity between old and young people will be like when the former represents a quarter of the population. Thus, if these facts are changing the status quo of the healthcare systems’ solidarity, why should we avoid discussing the solidarity between those who take care of their health and those engaging in unhealthy behaviours? Henceforth, we will call this kind of solidarity lifestyle solidarity (following Trappenburg, 2000).

There are empirical and theoretical reasons to hold people accountable for their lifestyle. As with many other forms of consumption, lifestyle choices produce external effects. Immediate negative externalities derive directly from acts of lifestyle consumption, such as passive smoking, violent and disorderly behaviour associated with alcohol abuse or traffic accidents resulting from reckless driving (Sassi & Hurst, 2008). Deferred externalities are also generated through the link between lifestyle choices and chronic diseases. Once chronic diseases emerge, the individuals affected will become less productive, possibly entirely unproductive, and they will make more intensive use of public medical and social services. As the World Health Organization (WHO) reported, most of the risk factors contributing to the disease burden can be attributed to an unhealthy lifestyle (WHO, 2021). Chronic noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are currently the leading cause of disability and death worldwide. These diseases result from genetic, physiological, environmental and behavioural factors. The main types of NCD (cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes) account for over 80% of all premature deaths (WHO, 2021). This burden is predicted to worsen in the coming years.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic shows that the virus affected people suffering from NCDs more. These statistics become even more important when general information about the relationship between health and lifestyle exists. It is common knowledge that one’s way of life partly determines one’s health—what one eats, how much one drinks, whether one smokes, how hard one works, whether one indulges in risky sexual behaviour, etcetera (Trappenburg, 2000). In some countries like Portugal, the idea of personal responsibility for health is enshrined in the constitution of the republic, where article 64º nº 1 explicitly says: ‘Everyone has the right to health protection and the duty to defend and promote it’ (CRP, 2021). The costs of NCD are increasingly threatening the financial sustainability of publicly funded health systems. A growing awareness that many medical needs are foreseeable and avoidable consequences of individual actions (Blank, 1997), which implies spending scarce resources on treatments of medical sufferings that, at least to some degree, could be avoided through personal lifestyle changes, raised several questions concerning lifestyle solidarity.

Personality Traits and Lifestyle Solidarity

Risk Preferences

Risk preference is one of the most crucial building blocks of choice theories in behavioural science. Risk preference is often understood to represent a dispositional trait. A growing body of research in economics and psychology has linked individual risk attitudes to a wide range of behavioural patterns, such as health outcomes (Lönnqvist et al., 2015). Moreover, economic research has traditionally focused on individual decision-making without incorporating the influence of society on risk preferences (Batteux et al., 2019; Füllbrunn & Luhan, 2019). Many risky decisions affect other people through the distribution of income and wealth in society. At the same time, people often disagree about the fair allocation of gains and losses that inevitably result from risky choices. In the health context, the concept of risk had become timely with the COVID-19 pandemic when biased behaviours of some individuals became a source of threat for the whole group. Country experiences have revealed that biased behaviours of individuals and organizations have led to the resurgence of infected cases, resulting in a second and even a third wave of infection in several countries worldwide (Jemli & Chtourou, 2023). Some individuals take more risks by engaging in harmful health-related behaviours, creating risky situations for themselves (lower health status) and for others who do not engage in those behaviours. Those who pursue unhealthy behaviours face the risk of getting sick and the risk that treatments will prove less effective.

Moreover, engaging in risky behaviours puts pressure on the public health system by having to cover the increasing expenses of treating health-related illnesses (that could be avoided), jeopardising the treatment of other diseases. Indeed, those who lead a more orderly life bear the risk of, for the sake of others, having fewer resources available in the future. Thus, under healthcare scarcity, how do individuals’ risk preferences influence the support for lifestyle solidarity? More precisely, if priorities between patients have to be established, would individual risk preferences support the rationing criterion of personal responsibility?

While it is widely recognized that individual risk attitudes are an important factor in health (Arrieta et al., 2017) risk attitudes in medical resource-allocating decisions have yet to be studied. To date, no model is that incorporates risk preferences in a patient priority-setting context is available when lifestyle is the main rationing criterion. Thus, we have non-clearly formulated hypotheses before the study. However, we may develop some research questions based on the relationship between risk preferences and (i) moral judgments through the personality dimensions of the Big-Five model and (ii) the predisposition to engage in unhealthy lifestyles through time preferences.

There has been a growing investigation of the relationship between risk preferences and personality traits across the Big-Five model (Lönnqvist et al., 2015; Baffour et al., 2019; Pavlíček et al., 2021). The findings revealed that people with a dominant extraversion (self-confidence, active and excitement seeking, positive emotions and intense personal interactions) and openness to experience (impulsive, willing to undergo new experiences and try new things, liberal in their values and flexible to norms) are more risk-tolerant. In contrast, neurotic people (insecurity, anxiety, negative affections, instability, worrisome, interpersonal hostility, anger and depression), conscientious people (responsible, goal-oriented, self-discipline) and agreeableness people (trusting in others, caring likeableness, build harmonious interpersonal relationships, altruistic, selfless and helpful) can feel more difficult in making complex or risky decisions.

Experimental research has shown that measures of risk and time preferences are good predictors for individual health-related behaviours such as food intake (Chabris et al., 2008) and physical exercise (Leonard et al, 2013). Indeed, decisions such as changing eating patterns or being physically active entail a cost in the present but decrease health risks in the future. These associations denote that risk-prone (or risk-averse) attitudes are associated with greater (or lesser) levels of delay discounting with a more present (future) orientation as well as reveal a more (or lesser) tendency to engage in healthy-related risky behaviours (Mishra & Lalumière, 2017; Dieteren et al., 2020; Herberholz, 2020). Individuals who engage in risky behaviours tend to possess higher personality traits associated with poorer impulse control (low self-control, high impulsivity) and greater sensation-seeking (Zuckerman, 2007) in line with the personality traits of extraversion and openness to experience. Thus, based on the idea that human beings prefer the distribution mechanism that is the most advantageous for them, risk orientation can be relevant for lifestyle solidarity. If risk-prone individuals tend to lead harmful lifestyles to their health, they would also be more tolerant of other co-citizens who engage in the same pattern of risky behaviours.

Bearing in mind the preceding, we raise the following research questions:

RQ1: Do risk preferences influence the support for lifestyle solidarity in the context of healthcare scarcity?

RQ2: Do risk preferences relate to one’s lifestyle-related health behaviour?

Dispositional Optimism

Dispositional optimism is the generalised, relatively stable tendency to expect good outcomes across important life domains (Scheier & Carver, 2018). There is convergent evidence that optimism has a neurobiological basis (Hecht, 2013) while genetic (Mosing et al., 2009), social factors (Boehm et al., 2015) as well as culture (Fischer & Chalmers, 2008) may also affect dispositional optimism.

There is ample evidence that optimism and pessimism have implications in all life circumstances (Scheier & Carver, 2018). Dispositional optimism strongly affects our mental, economic, physical, and social state (Carver et al., 2010). Optimism has been associated with more positive outcomes mainly because optimists and pessimists have different coping strategies and motivations for reaching objectives (Carver & Scheier, 2014). Optimists are more proactive in solving problems, are more effective when confronted with adversities, are more efficient in risk scanning, are more confident in goal achievement and make more efforts to reach them. Proactive coping refers to steps people take to prevent an unwanted event from occurring rather than just reacting to adversity after it has already arisen. In the health domain, it suggests that optimists may prefer investing in prevention over treatment to avoid bad outcomes in the future. Health behaviour research has investigated the relationship between dispositional optimism and lifestyle factors and found that optimists are likelier than pessimists to engage in health-promoting behaviours to stay physically healthy (Pänkäläinen et al., 2018; Dohmen et al., 2019; Rogowska et al., 2021). Moreover, when trade-offs in investing efforts are needed, optimists seem to spend more effort to enhance goals with favourable odds (Pavlova & Silbereisen, 2013). Translated to the health context, it suggests that optimists will set lower priorities on healthcare with more uncertain health benefits. A relationship seems also to exist between optimism and time preferences. Higher levels of optimism are associated with higher discounting for time preferences (Berndsen & Van der Pligt, 2001), as with risk-tolerant individuals.

Psychological research found that optimism remains undefined within the Big-Five model (Carver & Scheier, 2014). While some evidence points out that optimism represents a blend of neuroticism and extraversion (Marshall et al., 1992), others found some overlap with agreeableness and conscientiousness (Sharpe et al., 2011). Furthermore, optimism is also associated with higher emotionality. More optimistic individuals experience more positive affections and prosocial behaviour as they focus more on their success expectations than pessimistic individuals, who feel more anguish and adversity (Baumsteiger, 2017). Prosociality is the tendency to engage in generous behaviours for the benefit of others, even when costly for oneself (Penner et al., 2005). In social interaction, the cognitive effect of positive affection acts as a driver and motivational mechanism for transcending self-interest, leading to helping, generosity, and interpersonal understanding (Carver & Scheier, 2014; Isen, 2001).

It is worth mentioning that the dispositional optimism construct has its limitations. While dispositional optimism has been found to affect several outcomes positively, some researchers have argued that excessive optimism (unrealistic optimism) can lead to overconfidence, unrealistic expectations, and poor decision-making (Shepperd et al., 2015). In the health context, unrealistic optimism among smokers lowers the intentions to quit smoking (Dillard et al., 2006), while unrealistic optimism about avoiding the H1N1 virus corresponded with lower intentions to perform hand hygiene practices (Kim & Niederdeppe, 2013). Recent research has investigated the link between optimism and risk preferences and found that risk-taking behaviour is determined by the disposition to focus on favourable or unfavourable outcomes of risky choices (Dohmen et al., 2019). It is argued that the underlying mechanism is that optimists tend to take more risks precisely because they focus more on good outcomes. Thus, despite dispositional optimism’s relevance on lifestyle solidarity, its impact is unclear. Based on the literature described above, risk preferences and dispositional optimism can be important drivers of how people support lifestyle solidarity when setting priorities among patients. Thus, we raise the following research questions:

RQ3: Does dispositional optimism influence the support for lifestyle solidarity in the context of healthcare scarcity?

RQ4: Does dispositional optimism relate to one’s own lifestyle-related health behaviour?

RQ5: Does one’s own lifestyle influence the support for lifestyle solidarity?

RQ6: Are the traits of dispositional optimism and risk preferences related?

Methods

Survey Process and Data Collection

Data were collected through an online questionnaire performed in google forms made available between April and July 2019 on social networks (Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter and Google Plus) and spread through the personal contacts of the authors. The conditions for participation in the questionnaire were validated through two questions. The first question was related to the participants’ residence in Portugal: ‘Do you currently live in Portugal?’. The answer ‘yes’ allowed proceeding to the second question of the questionnaire. In case of ‘no’ answer, participation in the questionnaire ended. The second question was about age: ‘Are you over 18 years old?’. The answer ‘yes’ allowed proceeding to the remaining questionnaire questions. The answer ‘no’ implied the end of the survey. In this way, we guarantee that participants meet two criteria cumulatively: they reside in Portugal and are over 18 years old. Thus, a non-probabilistic convenience sampling was applied.

The questionnaire was tested through a previous sample of 15 participants to verify and analyze the overall degree of comprehension and answer variability. In defining the pilot sample, we were careful to choose participants who presented different socio-demographic and economic characteristics (gender, age, education and financial situation) to represent the items of socio-demographic and economic characterization that we intended to measure. Seven men and eight women with an average age of 37.6 years were included in the pre-test. Two participants had a primary education, three completed secondary education, five were licensed, and five were masters or doctors. Four participants had an income of less than 1000 euros, four between 1001 and 2000 euros, four between 2001 and 3000 euros, and three greater than 3000 euros. Participation was voluntary, explicit informed consent was given, all potential participants were informed about the purpose of the research, and anonymity was granted.

Data Measurement

The questionnaire contains four sections, each composed of questions that measure the variables used in the present study. All questions have a mandatory answer.

Section 1 collected respondents’ sociodemographic and economic characteristics such as gender, age, education, perceived personal financial situation, private health insurance and political orientation.

Section 2 collected information concerning respondents’ own lifestyles (OwnL), and risk preferences. To report the effect of OwnL, participants answered ten questions regarding their health behaviours, including their diet, exercise, smoking, drinking, use of non-prescription drugs, time spent on the internet, and mobile devices, aggressive driving, non-protected sun exposure and non-protected sex activity. Items were answered using a three-point rating scale (1, never; 2, sometimes; 3, always) except for time spent on the internet and mobile devices, where a two-point rating scale was used (1, more than 2 h/day; 2, less than 2 h/day). The sum of the scores of each item computed the score of respondents’ OwnL. To measure risk orientation, we asked respondents ‘how comfortable (uncomfortable) they are in taking a risk when making financial career or other life decisions’ (Maestas & Pollock, 2010). The answers were collected on a seven-point ordinal scale, where 1 (totally comfortable) represents extreme risk acceptance, and 7 (totally uncomfortable) represents extreme risk aversion. Respondents with values between 1 and 3 were considered risk-acceptance (RAC), while values between 5 and 7 were risk-averse (RAV). Risk-neutrals were the respondents scoring 4. We recoded this variable, as done elsewhere (Milita et al., 2019), so that lower scoring equals greater RAC (3 = 1; 2 = 2 and 1 = 3) and higher scores equals greater RAV (7 = 1; 6 = 2 and 5 = 3). RAC ranges from 1 to 3, with higher values denoting greater risk acceptance and ‘0’ denoting that respondent is either risk-averse or risk-neutral. Similarly, RAV ranges from 1 to 3, with higher values denoting greater risk aversion and ‘0’ denoting that respondent is either risk-acceptance or risk-neutral.

Section 3 collected information to measure dispositional optimism. Respondents provided answers to the revised life orientation test (LOT-R) (Scheier et al., 1994) that comprises ten items (Table A1 in Appendix), of which three measure optimism (OPT), three measures pessimism (PES), and four are filled items to distinguish the underlying purpose of the test. Respondents answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, ‘strongly disagree’, to 5, ‘strongly agree’. This scale was tested by previous studies documenting its reliability and validity (see Carver et al., 2010, for a review). Following some recommendations in the literature, we used two separate constructs in our analysis: an optimism score (OPT) and a pessimism score (PES) based on the three optimistic and three pessimistic items, respectively. We summed the scores of the items under consideration to obtain the OPT and PES scores.

Section 4 collected participants’ support for lifestyle solidarity (LifS). Respondents should indicate their level of agreement within eight statements concerning the relevance of information about diseases that were self-inflicted by harmful health behaviours (smoking, excessive alcohol intake, excessive time spent on internet/mobile devices, unbalanced diet, unprotected sun, and sex practice, illegal drug use and aggressive driving) for setting patients’ priorities, using a 5-point Likert scale (1, ‘strongly disagree’; 5, ‘strongly agree’). These eight statements and their scale were derived from some empirical literature (e.g. Bringedal & Feiring, 2011; Pinho & Araújo, 2022). Details of the questions can be found in the first column of Table A2 in the Appendix.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the main variables of the study. The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (25.0). The influence of the respondents’ personality traits and own lifestyle in supporting lifestyle solidarity was assessed through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with varimax-rotated factor matrices (to divide the indicators of latent variables by factors). Subsequently, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was implemented to confirm the reflective nature of the model to be tested. Then, the relationship between the personality traits of the interviewee and their own lifestyle with support for lifestyle solidarity was evaluated through the application of the Partial Least Squares (PLS) method in the Smart PLS 3.0 software (Ringle et al., 2019). The PLS methodology was chosen for two main reasons. First, due to the non-adjustment to the normal distribution of most of the items that constitute this instrument (Hair et al., 2019). Second, the data were collected through a questionnaire, with multiple indicators associated with the latent variables (Ringle et al., 2019). This method allows the combination of a factor analysis with regressions. The reliability of the instrument was evaluated through the composite reliability coefficients (CR), and its validity was tested through three measures (Hair et al., 2019): (i) Cronbach’s Alpha measurements (Cα > 0.70); (ii) composite reliability (CR > 0.70); (iii) Average Variance Extracted (AVE > 0.50) and (iv) discriminant validity tested by the Fornell-Larcker criterion. In this way, the data were analyzed in four steps:

-

(i)

Statistical analysis of latent variables and items that measure them;

-

(ii)

Implementation of an EFA and a CFA;

-

(iii)

Evaluation of the items that measure the constructs to ensure measurement validity and reliability of the model to be estimated;

-

(iv)

Bootstrap analysis to assess relationships between latent variables

Finally, a linear regression analysis was performed to identify the associations between respondents' sociodemographic and economic characteristics and their dispositional optimism, risk preferences and own lifestyles.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Although 721 citizens filled out the questionnaire, a sample of 584 Portuguese citizens (81%), was considered valid (questionnaires thoroughly answered). In 2021, Portugal had around 10,286 thousand inhabitants over 18 years old (FFMS, 2023). Considering a margin of error of 3%, a minimum of 1,068 responses would be required. As the number of valid responses in the study is lower, the sample cannot be considered representative of the Portuguese population.

The majority of respondents (61.8%) were female, most (67.5%) had higher education (graduation or MSc or Ph.D.), the predominant age (34.4% of respondents) ranges between 35 and 44 years old and most respondents recognize being in an economically comfortable (33.4%) or fair (49.7%) situation. Roughly half of the respondents said they had no political preference, and almost 30% said they were left-wing. Most participants (66.6%) have private health insurance. Risk acceptance (54.8% of respondents) prevails among respondents, followed by risk-averse (30%).

Figure 1 summarizes the OPT, PES, and OwnL variables using boxplots. OPT and PES values ranged from 3 to 15. Respondents scored higher on the OPT than PES scale. While the average (and median) optimism score was 10.8, the average (and median) pessimism was 7.5. The internal consistency of both variables was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.779 (OPT) and α = 0.749 (PES)). The OPT score correlated weakly with the three pessimistic items (between 0.209 and 0.304), and the PES score correlated weakly with the three optimistic items (between −0.359 and −0.268). The respondents’ own lifestyle score ranged from 10 to 28. Respondents revealed high adherence to healthy lifestyles, with an average (and median) score of 22.1. The internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.732).

Results from linear regression analysis presented in Appendix, Table A3, revealed that higher OPT scores are associated with older age, having private health insurance, and a comfortable economic situation. In comparison higher PES scores are associated with younger age, having a lower level of education (secondary), not having health insurance and a difficult economic situation. Concerning risk preferences, four variables were positively associated with higher RAC scores (and negatively with RAV scores): a higher level of education, a comfortable economic situation, owning private insurance, and having a right-wing orientation (left-wing orientation for RAV). Five variables were positively associated with higher adherence to a healthy lifestyle: being female, being older, having a post-university degree, having private health insurance, and a right-wing orientation.

Figure 2. summarizes respondents’ level of agreement with the importance of using lifestyle information to prioritize patients. These questions ranged from 1 to 5, and the mean for each question was less than 2.5, suggesting that most respondents disagree with the statements (for details, see Table A2 in the Appendix). Respondents revealed higher levels of lifestyle solidarity and there seems to be a homogeneous pattern among all eight risky behaviours. No significant statistical association was found between the support for lifestyle solidarity and the respondents’ sociodemographic variables.

Factor Analysis

Table 1 shows the results of the EFA. The 17 initial items collected were divided into six factors: factor 1 LifS, with eight items; factor 2 OPT, with three items; factor 3 PES, with three items; factor 4 RAC, with one item; factor 5 RAV, with one item and factor 6 OwL, with one item. No starting items have been removed. The six factors have a cumulative variance of 75.08%, where the most prominent factor (factor 1) explain the variation of 40.19% (no factor explains a variation greater than 50%). The 17 items have communalities greater than 0.50 that is sufficient to precede with the rotation of the factor matrix.

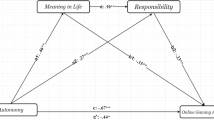

A CFA was also performed to specify the reflective nature of the measurement of items by latent variables (Hair et al., 2019). All items have high confirmatory factor loads (> 0.70), and, as such, no item was excluded (Table 2). Having validated the reflective nature of the measurement of the items, Fig. 3 presents the PLS model resulting from the PLS logarithm.

The latent variables are represented in circles and were measured by indicators represented in squares (explaining at least 50% of the variance of the latent variable with which they are associated). The predictive prediction is validated by the R2 values shown in the latent variable circles. According to Cohen (1988), the latent variables RAC (R2 = 0.133) and RAV (R2 = 0.130) have a ‘medium effect’, and the latent variables OwnL (R2 = 0.020) and LifS (R2 = 0.036) have a ‘small effect’. Regarding LifS variable, we verify that the explanatory power of all risk behaviours is considerable as they explain between 86.9% and 91.4% of the variance. For the OPT variable, it is interesting to note that the first question involving uncertainty (‘In uncertain times, I usually expect the best’) had the most significant explanatory power, being the most important question in defining optimism.

Measures of Reliability and Validity

Table 2 presents the values of the individual reliability of each variable as well as the AVE and its square root, indicators of the convergent and discriminant validity, respectively. The results reveal simultaneously high rates of reliability (Cα > 0.70 and CR > 0.70) and the existence of convergent (AVE > 0.50) and discriminant validity. Thus, the model is reliable and has factorial convergent and discriminant validity. Following Hair et al. (2019), the quality of the model fit was validated through the chi-square (p = 0.065), Goodness-of-Fit (0.95), the Comparative Fit Index (0.96), and standard root mean square residual (0.070). The Goodness-of-Fit Indices meet the reference values indicating that the estimated PLS model have a good fit.

Explanatory Analysis

Table 3 presents detailed results of the PLS bootstrap analysis. Significant relationships exist between the dependent and independent latent variables.

Association Between Personality Traits and Lifestyle Solidarity

Optimistic, and to a greater degree pessimistic respondents show little solidarity with patients engaging in harmful health behaviours. Higher levels of optimism (and pessimism) imply more penalties for risky behaviour (β = − 0.110 and β = − 0.123, respectively). Preferences for risk, conversely, determine greater lifestyle solidarity but only for risk-tolerant respondents (β = 0.127). A percentage increase in risk tolerance implies penalising risky behaviours 12.7% less. No statistically significant association was found for risk-averse participants.

Association Between Personality Traits and Own Lifestyle and Between Own Lifestyle and Lifestyle Solidarity

Participants who adhered to healthy lifestyles showed less solidarity with patients that engaged in risky behaviours (β = −0.105). Predicting a healthy lifestyle can mainly be predicted by respondents’ optimism (b = 0.131), while risk-seeking respondents were likelier to engage in harmful health-related behaviours (b = −0.019). The greater the respondents’ optimism (risk-prone), the greater (lesser) their concern about pursuing a healthy lifestyle.

Association Between Dispositional Optimism and Risk Preferences

Respondents’ optimism and pessimism interact with their risk preferences. More optimistic participants were revealed to be more risk-prone (β = 0.283), and less risk-averse (β = −0.293) as well as more pessimistic respondents were revealed to be more risk avoidance (β = 0.122) and less risk-prone (β = −0.142).

Discussion

It is widely acknowledged that lifestyle-related risk behaviours result in the spread of NCD and increase healthcare costs. As a result, there has been a growing interest in lifestyle and the consequences of unhealthy lifestyles for the healthcare systems. As the scarcity of resources in health becomes more evident and the demand for budgetary containment increases, lifestyle solidarity may be questioned. This remains, however, a controversial issue in the literature. While it might not seem fair to let other people pay for the costs arising from an unhealthy lifestyle, it also does not seem reasonable to punish people for their lifestyle. This study empirically analysed the degree of Portuguese solidarity with lifestyle in a hypothetical context of health scarcity, influenced by two personality traits—dispositional optimism and risk orientation and their lifestyles.

The results indicate that Portuguese respondents exhibited high solidarity with lifestyles, homogenous among the eight risky behaviours. Our findings are in line with those of other studies carried out in Portugal (Borges & Pinho, 2017; Pinho & Borges, 2019) and other countries (Bonnie et al., 2010; Miraldo et al., 2014; Pinho et al., 2022) indicating that the general public does not support the personal responsibility as a healthcare rationing criterion. Although worrying, the high support for lifestyle solidarity revealed by our respondents is not surprising. Portuguese society has been performing poorly in health-related lifestyle behaviours. Recent data showed that the Portuguese lead a sedentary lifestyle, their daily food intake is unbalanced, they have the highest alcohol consumption rates in Europe, and the percentage of smokers and illegal drug abusers is around 17% and 10.5%, respectively, while the road deaths are still above the European average (SICAD, 2022; ETSC, 2021). Indeed, our findings suggest that one’s own lifestyle was an important determinant of lifestyle solidarity. A negative association (following healthier lifestyles implies less lifestyle solidarity) was found between them in line with the rational choice theory, which assumes that people tend to prefer the distribution mechanism that is the most advantageous for them.

Our general hypothesis that personality traits matter for lifestyle solidarity was confirmed. According to our results, both dispositional optimism and risk orientation influence the support of the personal responsibility criterion, albeit in opposite directions. On the one hand, we found that dispositional optimism was associated with lower lifestyle solidarity. Respondents with either a more positive or negative outlook on the future were more likely to give less priority to patients who contributed to their illness through risky behaviours, although the pessimists were more penalising. This finding partially aligns with recent empirical research (Pinho & Araújo, 2022), suggesting that optimism was positively related to accepting personal responsibility. Our results also corroborate the idea described in the ‘Dispositional Optimism’ section that optimists easily disengage from goals with unfavourable odds (Geers et al, 2009). Indeed, we found that optimists set lower priorities for patients who engage in unhealthier lifestyles, probably because the health benefit achieved from the treatment is more uncertain. Although we corroborate the results of some studies (Geers et al., 2009; Pavlova & Silbereisen, 2013), others found no association between optimism and preferences for effectiveness (Luyten et al., 2019). Besides, another noteworthy finding was that optimists were more prevention-oriented when it comes to their health behaviours in line with other studies (Pänkäläinen et al., 2018; Rogowska et al., 2021; Steptoe et al., 2006), which may explain their lower solidarity with those that somehow neglected their health. However, other empirical findings found no relation between dispositional optimism and own lifestyle (Pinho & Araújo, 2022). We can only speculate about the reasons concerning the lower level of lifestyle solidarity shown by pessimists. A possible explanation may be that pessimists are inherently less emotional and experience non-prosocial behaviours. However, more research is needed here.

On the other hand, we found that risk orientation is partially associated with higher lifestyle solidarity. Risk-prone respondents were more likely to tolerate patients’ faults. Our survey also observed that risk-acceptant respondents were likelier to engage in harmful health behaviours. Their taste for adventure, higher impulsivity, and sensation-seeking inherent in an extraversion and openness to experience personality may explain risk-tolerant respondents’ increased solidarity with lifestyle, again suggesting adherence to the rational choice theory. As described in the ‘Risk Preference’ section, risk and time preferences are good predictors for individual health-related behaviours. Risk-seeking individuals demonstrate a greater delay discounting, a more present orientation and a lower appreciation of prevention. This is confirmed in research showing that risk-prone are less prevention-oriented with their health behaviours (Galizzi & Miraldo, 2017; Rouyard et al., 2018; Dieteren et al., 2020). Surprisingly, no relationship was found between risk-aversion and own lifestyle or lifestyle solidarity. The fact that most respondents reveal a propensity for risk (almost 55%) may explain this result. An interesting finding was the positive association between both personal traits. Indeed, in line with elsewhere results (Dohmen et al., 2019), we found that optimism is related to risk-seeking preferences while pessimism is related to aversion to risk. We can only speculate about the reason for this association. Possibly, optimists have a more positive outlook on the future, are more confident that goals are achievable, see fewer impediments that reinforce motivation, and become a source of support in achieving new goals or coping with adversity, making them more risk-tolerant. Moreover, the question involving uncertainty had a greater weight in defining optimism, which may corroborate our speculation. Furthermore, optimistic individuals can seek more risk behaviours because they may be contagious by unrealistic optimism that leads to overestimating personal control (Shepperd et al, 2015). This matter deserves further investigation.

We found no association between respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle solidarity and few associations between them and personal traits or lifestyles. A favourable economic situation and being protected by private health insurance were important determinants of OPT, RAC and engaging in a healthy lifestyle. At the same time age only influenced OPT and higher education and having a right-wing political orientation had a positive influence on being risk-prone and avoiding harmful health behaviours. It is easy to understand that having a comfortable economic situation allows a more positive outlook on the future and increases the propensity to take risks. This relationship between personal financial situation and personal traits (OPT and RAC) is interesting and raises questions that should be investigated. Besides, more money and more education explain more prevention-orientation attitudes regarding their health behaviours. These findings are corroborated elsewhere (Bonnie et al., 2010). Finally, a more right-wing political orientation induced healthy behaviours and risk-seeking. Although these findings align with those of other studies (Choma et al., 2014; Han et al, 2019), they contradict others (Kannan & Veazie, 2018).

In terms of limitations, the study’s findings should be interpreted with appropriate caution, given the non-random nature of the sample. The results cannot be generalised to the Portuguese general public. On average, women were overrepresented, and the sample was younger and better educated than the general Portuguese population. In 2022, the average age of the Portuguese population was 46.8 years, and 20% had an undergraduate education (FFMS, 2023). Additionally, and probably because the sample tends to be young, risk seekers were overrepresented. However, the main aim here was not to accurately represent the opinions of the Portuguese people in general but rather to deepen research on healthcare rationing by incorporating the role of personality. Besides this sampling limitation, there are limitations in using an online questionnaire that raise concerns regarding the quality of the data obtained, namely the potential for social desirability bias. However, in recent years, there has been an increasing interest in collecting data online (Rowen et al., 2016), and most studies find an overall, broadly similar response throughout the different survey administration modes (Rowen et al., 2016). The use of hypothetical scenarios is also a limitation of the study. Furthermore, we are aware that deciding which patient to treat based on health-related behaviours poses many ethical concerns, not the least of which is to know to what extent the risk behaviours contributed effectively to the illness. Although some studies (Alberg et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2007) establish direct relationships, these are difficult to predict in all cases. Furthermore, we should bear in mind that there may be genetic predispositions to have certain chronic diseases or that certain lifestyles can be triggered by environmental, socio or psychological factors (Venkatapuram & Marmot, 2009; Øvrum & Rickertsen, 2015; Resnik, 2014). Finally, our results are mainly descriptive since the present study does not incorporate perceptions about these ethical considerations. It is our contention that the contribution of this study overcomes these drawbacks.

Conclusion

The analysis of the influence of dispositional optimism and risk orientation on supporting lifestyle solidarity (in a healthcare rationing context) and one’s lifestyle is important to define explicit healthcare rationing criteria based on personal responsibility. Given the findings, the study has shown that Portuguese respondents overall support lifestyle solidarity. Although this support was positively related to respondents’ lifestyles and risk acceptance orientation, it was negatively associated with respondents’ dispositional optimism. Furthermore, both personality traits were linked since being optimistic (or pessimistic) was positively related to being risk-prone (or risk-averse).

With this empirical investigation, we prove that personality traits and citizens’ health-related behaviours influenced value judgments concerning allocating scarce healthcare resources. This study was the first in the literature on healthcare rationing relating dispositional traits and risk orientation with one’s own lifestyle and lifestyle solidarity.

Theoretical Implications

This paper suggests that dispositional optimism and risk orientation highlight how people want to consider personal responsibility as an explicit criterion to set healthcare priorities. We confirm the theory recognized in psychology that personality traits have a role in shaping how people feel, think and behave (Corr & Matthews, 2009) and extend it to the health field. Thus, since we confirm that these two personality traits influence how someone makes the value judgments inherent to priority setting, future empirical research should carefully select their sample by granting representativeness of dispositional optimism and risk orientation. This need is reinforced by the two personality traits being closely related. Thus, more than selecting a sample by their sociodemographic characteristics their personality trait should also be considered.

Managerial Implications

Useful policy implications can be revealed from the results of this article. First, although the study results suggest great support for lifestyle solidarity, this support is lesser among individuals who engage in healthy behaviours. The findings of the present study indicate that Portuguese respondents adhere to the rational choice theory. Since Portuguese civil society has a poor performance regarding health behaviours, this should be a warning to take political measures that encourage societies' behavioural change in favour of health. Although the Portuguese government has already adopted measures such as increasing taxes on drinks with high sugar content, they need to be revised and should cover behaviours beyond food. In this regard, the Portuguese government now has a great opportunity through the advantage of an absolute majority in parliament to approve measures that incentivise healthy-related behaviours. According to our findings, a society more prone to adopting healthy lifestyles will be a society that is less tolerant of citizens who prevaricate in behavioural terms, thus jeopardising the scarce health resources that belong to everyone. Second, literacy campaigns should be developed to discuss publicly the rights and duties associated with a healthcare system grounded in solidarity. Civil society must understand that it should do everything in its power to maintain good health. They should be aware that if healthcare is funded as a form of mutual support, the health system has the right to penalise some users responsible for their poor health since those who avoidably incur health burdens violate obligations of solidarity. We believe that in developed countries, the eminent economic difficulties and a greater awareness of resource scarcity will shortly replace the current ‘social state’ system with the ‘enabling state’, in which residents are responsible for their own well-being. This means that solidarity is no longer unrestricted but is becoming dependent on peoples' responsible behaviour. Finally, as a manager of expectations, the government should take advantage of the current context of imminent economic recession caused by inflation and rising interest rates to start discussing the definition of explicit healthcare rationing criteria since healthcare resources are insufficient for everyone who needs them. The pessimism that seems to plague civil society may be an opportunity, in light of our finding that dispositional optimism (mainly pessimism) is negatively related to lifestyle solidarity, for the government to find support for health rationing criteria that are more controversial, such as personal responsibility for the disease.

Suggestions for Future Research

Our results and suggested explanations open up possibilities for further research. In follow-up research, it would be helpful to investigate the role of risk preferences in health deeply. Our findings call for more research on risk attitudes on health allocation decisions. Yet some evidence shows that risk attitudes differ by domain (Soane & Chmiel, 2005; Prosser & Wittenberg, 2007), which deserves to be explored more in the context of patients’ priority-setting. Besides, future works should consider the factors that shape the extent to which individuals perceive them as exposed to risk, in this case, exposed to the chance that the health system will not have the resources to treat you or a family member. Moreover, as we found that personality traits influence preference for rationing healthcare, exploring the influence of more personality traits across, for example, the Big-Five trait dimensions would be interesting. Furthermore, future studies could use a representative sample of Portuguese citizens and beyond the Portuguese population and experimental study designs to elicit social preferences. Through experimental study designs, the consistency of the results can be assessed by manipulating both optimism and risk orientation. Finally, it would be helpful to explore respondents’ ethical considerations by understanding the motivations behind their choices through qualitative methods.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Alberg, A., Brock, M., & Samet, J. (2005). Epidemiology and lung cancer: Looking to the future. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(14), 3175–3185.

Albertsen, A., & Knight, C. (2015). A framework for luck egalitarianism in health and healthcare. Journal of Medical Ethics, 41(2), 165–169.

Arrieta, A., García-Prado, A., González, P., & Pinto-Prades, J. (2017). Risk attitudes in medical decisions for others: An experimental approach. Health Economics, 26(Suppl 3), 97–113.

Baffour, P., Mohammed, I., & Rahaman, W. (2019). Personality and gender differences in revealed risk preference: Evidence from Ghana. International Journal of Social Economics, 46(5), 631–647.

Batteux, E., Ferguson, E., & Tunney, R. (2019). Do our risk preferences change when we make decisions for others? A meta-analysis of self-other differences in decisions involving risk. PLoS ONE, 14(5), e0216566.

Baumsteiger, R. (2017). Looking forward to helping: The effects of prospection on prosocial intentions and behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47, 505–514.

Berndsen, M., & Van der Pligt, J. (2001). Time is on my side: Optimism in intertemporal choice. Acta Psychologica, 108(2), 173–186.

Blank, R. (1997). The Price of Life. Columbia University Press, New York.

Boehm, J. K., Chen, Y., Williams, D. R., Ryff, C., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2015). Unequally distributed psychological assets: Are there social disparities in optimism, life satisfaction, and positive affect? PLoS ONE, 10(2), e0118066.

Bonnie, L., Akker, M., Steenkiste, B., & Vos, R. (2010). Degree of solidarity with lifestyle and old age among citizens in the Netherlands: Cross-sectional results from the longitudinal SMILE study. Journal of Medical Ethics, 36(12), 784–790.

Borges, A., & Pinho, M. (2017). Should lifestyles be a criterion for healthcare rationing? Evidence from a Portuguese survey. Journal of Research in Health Sciences, 17(4), 1–7.

Borghans, L., Duckworth, A., Heckman, J., & Weel, B. (2008). The economics and psychology of personality traits. The Journal of Human Resources, 43, 972–1059.

Bringedal, B., & Feiring, E. (2011). On the relevance of personal responsibility in priority setting: A cross-sectional survey among Norwegian medical doctors. Journal of Medical Ethics, 37, 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.038844

Cappelen, A., & Norheim, O. (2006). Responsibility, fairness and rationing in health care. Health Policy, 76, 312–319.

Cappelen, A., & Norheim, O. (2005). Responsibility in health care: A liberal egalitarian approach. Journal of Medical Ethics, 31, 476–480.

Carver, C., & Scheier, M. (2014). Dispositional optimism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(6), 293–299.

Carver, C., Scheier, M., & Segerstrom, S. (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 879–889.

Chaabouni, S., & Mbarek, M. (2023). What will be the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the human capital and economic growth? Evidence from Eurozone. Journal of Knowledge Economy (ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01328-3

Chabris, F., Laibson, D., Morris, C., Schuldt, J., & Taubinsky, D. (2008). Individual laboratory-measured discount rates predict field behavior. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 37(2–3), 237.

Choma, B., Hanoh, Y., Hodson, G., & Grummerum, M. (2014). Risk propensity among liberals and conservatives: The effect of risk perception, expected benefits, and risk domain. Social Psychology and Personality Science, 6(5), 713–721.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Corr, P., & Matthews, G. (2009). The Cambridge handbook of personality psychology. Cambridge University Press.

CRP - Constituição da República Portuguesa. (2021). 8ª ed. Coimbra. Almedina.

Davies, B., & Savulescu, J. (2019). Solidarity and responsibility in health care. Public Health Ethics, 12(2), 133–144.

Dieteren, C., Brouwer, W., & Van Exel, J. (2020). How do combinations of unhealthy behaviors relate to attitudinal factors and subjective health among the adult population in the Netherlands? BMC Public Health, 20, 441.

Dillard, A., McCaul, K., & Klein, W. (2006). Unrealistic optimism in smokers: Implications for smoking myth endorsement and self-protective motivation. Journal of Health Communication., 11(Suppl1), 93–102.

Dohmen, T., Quercia, S., & Willrodt, J. (2019). Willingness to take risk: The role of risk conception and optimism. SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research, No. 1026, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin.

Dolan, P., Shaw, R., Tsuchiya, A., & Williams, A. (2005). QALY maximization and people’s preferences: A methodological review of the literature. Health Economics, 14(2), 197–208.

Ehrlich, S., & Maestas, C. (2010). Risk orientation, risk exposure and policy opinion: The case of free trade. Political Psychology, 31(5), 657–684.

ETSC – European Transport Safety Council. (2021). Road deaths in the European Union. Available at: https://etsc.eu/euroadsafetydata/

FFMS. (2023). CENSOS DE PORTUGAL EM 2021. Retrieved drom: https://www.pordata.pt/portugal (Accessed 15 Mar 2023).

Fischer, R., & Chalmers, A. (2008). Is optimism universal? A meta-analytical investigation of optimism levels across 22 nations. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(5), 378–382.

Füllbrunn, S., & Luhan, W. (2019). Decision making for others: The case of loss aversion. Economics Letters, 161, 154–156.

Galizzi, M., & Miraldo, M. (2017). Are you what you eat? Healthy behaviour and risk preferences. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 17(1), 20160081.

Garpenby, P., & Nedlund, A.-C. (2016). Political strategies in difficult times - The “backstage” experience of Swedish politicians on formal priority setting in healthcare. Social Science & Medicine, 163, 63–70.

Geers, A., Wellman, J., & Lassiter, G. (2009). Dispositional optimism and engagement: The moderating influence of goal prioritization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 913–932.

Gu, Y., Lancsar, E., Ghijben, P., Butler, J., & Donaldson, C. (2015). Attributes and weights in healthcare priority setting: A systematic review of what counts and to what extent. Social Science & Medicine, 146, 41–52.

Hair, J., Risher, J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24.

Han, K., Jung, J., Mittal, V., Zyung, J., & Adam, H. (2019). Political identity and financial risk taking: Insights from social dominance orientation. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(4), 581–604.

Hecht, D. (2013). The neural basis of optimism and pessimism. Exp Neurobiol, 22(3), 173–199.

Herberholz, C. (2020). Risk attitude, time preference and health behaviours in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 87, 101558.

Isen, A. (2001). An influence of positive affect on decision making in complex situations: Theoretical issues with practical implications. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 11(2), 75–85.

Jemli, R., & Chtourou, N. (2023). Economic agents’ behaviors during the coronavirus pandemic: Theoretical overview and prospective approach. Journal of Knowledge Economy, 14, 3818–3846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-022-01027-5

Jüttemann, A., & Wirth, M. (2021). Live and let die: What we learned from US healthcare and what seems to be valid in the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, 633222.

Kannan, V., & Veazie, P. (2018). Political orientation, political environment, and health behaviors in the United States. Preventive Medicine, 114, 95–101.

Kim, H., & Niederdeppe, J. (2013). Exploring optimistic bias and the integrative model of behavioral prediction in the context of a campus influenza outbreak. Journal of Health Communication., 18(2), 206–222.

Leonard, T., Shuval, K., Oliveira, A., Skinner, C., Eckel, C., & Murdoch, J. (2013). Health behavior and behavioral economics: Economic preferences and physical activity stages of change in a low-income 241 African-American community. American Journal of Health Promotion, 27(4), 211–221.

Levy, N. (2018). Responsibility as an obstacle to good policy: The case of lifestyle related disease. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 15(3), 459–468.

Lönnqvist, J.-E., Verkasalo, M., Walkowitz, G., & Wichard, P. (2015). Measuring individual risk attitudes in the lab: Task or ask? An empirical comparison. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 4663.

Luyten, J., Kessels, R., Desmet, P., Goos, P., & Beutels, P. (2019). Priority-setting and personality: Effects of dispositional optimism on preferences for allocating healthcare resources. Social Justice Research, 32, 186–207.

Maestas, C., & Pollock, W. (2010). Measuring generalized risk orientation with a single survey item. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1599867

Marshall, G., Wortman, C., Kusulas, J., & Hervig, L. (1992). Distinguishing optimism from pessimism: Relationships to fundamental dimensions of mood and personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 1067–1074.

Milita, K., Bunch, J., & Yeganeh, S. (2019). It could happen to you: How perceptions of personal risk shape support for social welfare policy in the American State. Journal of Public Policy, 40(4), 535–552.

Minkler, M. (1999). Personal responsibility for health? A review of the arguments and the evidence of century’s end. Health Education Behavior, 26, 121–140.

Miraldo, M., Galizzi, M., Merla, A., Levaggi, R., Schulz, P., Auxilia, F., Castaldi, S., & Gelatti, U. (2014). Should I pay for your risky behaviours? Evidence from London. Prev Med., 66, 145–158.

Mishra, S., & Lalumière, M. (2017). Associations between delay discounting and risk-related behaviors, traits, attitudes, and outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 30(3), 7693–7781.

Mosing, M., Zietsch, B., Shekar, S., Wright, M., & Martin, N. (2009). Genetic and environmental influences on optimism and its relationship to mental and self-rated health: A study of aging twins. Behavior Genetics, 39(6), 597–604.

Nicholson, N., Soane, E., Fenton-O’Creevy, M., & Willman, P. (2005). Personality and domain specific risk taking. Journal of Risk Research, 8, 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1366987032000123856

OECD. (2019). Projections of health expenditure, in Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/3d1e710c-en

Olsen, J., Richardson, J., Dolan, P., & Menzel, P. (2003). The moral relevance of personal characteristics in setting health care priorities. Social Science & Medicine, 57(7), 1163–1172.

Øvrum, A., & Rickertsen, K. (2015). Inequality in health versus inequality in lifestyles. Nordic Journal of Health, 1, 18–33.

Paetz, F. (2021). Personality traits as drivers of social preferences: A mixed logit model application. Journal of Business Economics, 91, 303–322.

Pänkäläinen, M., Fogelholm, M., Valve, R., Kampman, O., Kauppi, M., Lappalainen, E., & Hintikka, J. (2018). Pessimism, diet, and the ability to improve dietary habits: A three-year follow-up study among middle-aged and older Finnish men and women. Nutrition Journal, 17, 92.

Pavlíček, A., Hintošová, A., & Sudzina, F. (2021). Impact of personality traits and demographic factors on risk attitude. SAGE Open, 11(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211066917

Pavlova, M., & Silbereisen, R. (2013). Dispositional optimism fosters opportunity-congruent coping with occupational uncertainty. Journal of Personality, 81(1), 76–86.

Penner, L., Dovidio, J., Piliavin, J., & Schroeder, D. (2005). Prosocial behavior: Multilevel perspectives. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 365–392.

Pinho, M., & Borges, A. (2019). The views of health care professionals and laypersons concerning the relevance of health-related behaviors in prioritizing patients. Health Education & Behavior, 46(5), 728–736.

Pinho, M., & Araújo, A. (2022). Personality and perceptions about the use of personal responsibility for illness as a health care rationing criteria. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 15(3), 137–151.

Pinho, M., Durão, N., & Zahariev, B. (2022). Are individual risky behaviours relevant to healthcare allocation decisions? An exploratory study. International Journal of Health Governance, 27(3), 342–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHG-01-2022-0011

Prosser, L., & Wittenberg, E. (2007). Do risk attitudes differ across domains and respondent types? Med Decision Making, 27(3), 281–287.

Resnik, D. (2014). Genetics and personal responsibility for health. New Genet Soc., 33(2), 113–125.

Ringle, C., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., & Gudergan, S. (2019). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31, 1617–1643.

Rogowska, A., Nowak, P., & Kwaśnicka, A. (2021). Healthy behavior as a mediator in the relationship between optimism and life satisfaction in health sciences students: A cross-sectional study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 24(14), 1877–1888.

Rouyard, T., Attema, A., Baskerville, R., Leal, J., & Gray, A. (2018). Risk attitudes of people with ‘manageable’ chronic disease: An analysis under prospect theory. Social Science & Medicine, 214, 144–153.

Rowen, D., Brazier, J., Keetharuth, A., & Tsuchiya, A. (2016). Comparison of modes of administration and alternative formats for eliciting societal preferences for burden of illness. Applied Health Econ Health Policy, 14(1), 89–104.

Sassi, F., & Hurst, J. (2008). The prevention of lifestyle-related chronic diseases: An economic framework (OECD Health Working Paper No. 32). Retrieved from: http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/40324263.pdf

Shepperd, J., Waters, E., Weinstein, N., & Klein, W. (2015). A primer on unrealistic optimism. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(3), 232–237.

Scheier, M., & Carver, S. (2018). Dispositional optimism and physical health: A long look back, a quick look forward. American Psychologist, 73(9), 1082–1094.

Scheier, M., Carver, C., & Bridges, M. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1078.

Segall, S. (2009). Health, Luck, and Justice. Princeton University Press.

Sharpe, J., Martin, N., & Rooth, K. (2011). Optimism and the Big Five factors of personality: Beyond neuroticism and extraversion. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(8), 946–951.

SICAD. (2022). Statistical Bulletin 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.sicad.pt/EN/Publicacoes/Paginas/default.aspx

Soane, E., & Chmiel, N. (2005). Are risk preferences consistent? The influence of decision domain and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(8), 1781–1791.

Steptoe, A., Wright, C., Kunz-Ebrecht, S., & Iliffe, S. (2006). Dispositional optimism and health behaviour in community-dwelling older people: Associations with healthy ageing. The British Journal of Health Psychology, 11(PT1), 71–84.

Taylor, R., Najafir, F., & Dobson, A. (2007). Meta analysis of studies of passive smoking and lung cancer: Effects of study type and continent. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(5), 2048–1054.

Traina, G., & Feiring, E. (2019). Being healthy, being sick, being responsible: Attitudes towards responsibility for health in a public healthcare system. Public Health Ethics, 12(2), 145–157.

Trappenburg, M. (2000). Lifestyle solidarity in the healthcare system. Health Care Analysis, 8, 65–75.

Venkatapuram, S., & Marmot, M. (2009). Epidemiology and social justice in light of social determinants of health research. Bioethics, 23(2), 79–89.

WHO. (2021). Noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

Williams, A. (1988). Ethics and efficiency in the provision of health care. In M. Bell & S. Mendus (Eds.), Philosophy and Medical Welfare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zuckerman, M. (2007). Sensation seeking and risky behavior. American Psychological Association.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the UIDB/05105/2020 Program Contract, funded by national funds through the FCT I.P.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for Publication

The authors declare that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere nor is it currently under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pinho, M., Gomes, S. Unveiling the Impact of Personality in Lifestyle Solidarity: An Exploratory Study of the Effects of Dispositional Optimism and Risk Orientation. J Knowl Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01702-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01702-1