Abstract

The relationship between entrepreneur’s gender and business performance has been studied in existing literature assuming that it is a straight-forward direct relationship. Instead, in this study we examine how gender affects business performance through the introduction of innovations. Our aim is to explore the differences between men-led and women-led businesses as regards the performance results they obtain from innovating. We use a sample of 1376 Spanish small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to analyse the effect of entrepreneur’s gender on business performance considering the mediating effect of innovations, that is, the possibility that gender indirectly influences business performance by affecting the introduction of innovations. Using econometric techniques, we estimate discrete choice models to investigate the relationship amongst gender, innovations and performance. Our main results show that men-led SMEs are more likely to achieve superior performance from innovations, and particularly, from their higher propensity to implement process innovations, in comparison to women-led SMEs. One limitation of our study is that data is cross-sectional, so that caution is needed regarding the causal interpretation of results. We contribute to uncover the role of gender on SMEs performance and the need to incorporate a policy gender perspective when dealing with enhancing SMEs innovativeness and performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the last decades, women entrepreneurship has increased substantially worldwide and its analysis and promotion have received increased attention from researchers and policy makers (Kelley et al., 2011; OECD, 2017; Brush et al., 2020; Ben Slimane & M’henni, 2020; Martínez-Rodríguez et al., 2022). Recent studies have revealed that entrepreneur’s gender influences firm’s innovation behaviour as regards the types of innovation implemented by the firm (Expósito et al., 2021; Marvel et al., 2015; Strohmeyer et al., 2017).Footnote 1 Also, the literature analysing the impact of the entrepreneur’s gender on business performance has experienced a significant development in the last decade (Alsos et al., 2013; Chabaud & Lebègue, 2013; Marvel et al., 2015; Coleman, 2016; Barrientos-Marín et al., 2021; Kiefer et al., 2022; Lemma et al., 2022). However, most of this literature has basically focused on nascent entrepreneurs, not devoting enough attention to the role of the entrepreneur’s gender on the innovation profile of established firms and on its impact on business performance (Kiefer et al., 2022). Hence, the role of entrepreneur’s gender on how innovations may impact business performance remains insufficiently explored (Elam et al., 2019; Link, 2017). Women entrepreneurs may face higher obstacles to implement innovations, compared to men, due to a lower access to financial resources, lack of human capital and innovation networks, amongst other (Cowling et al., 2020; Fairlie & Robb, 2009; Kiefer et al., 2022; Lemma et al., 2022; Marlow, 2020; Orser & Riding, 2018). As a consequence, the performance of businesses run by women entrepreneurs might be poorer when compared to their male counterparts. To our knowledge, no empirical study has paid attention to the possibility of entrepreneur’s gender indirectly influencing business performance by affecting the types of innovations introduced by the firm.

In this study, we aim at filling this gap by empirically exploring the mediation effect of firms’ innovations in the relationship between the entrepreneur’s gender and different dimensions of business performance. In particular, our research questions are as follows. Does the gender of the entrepreneur matter in the performance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs)? Do innovations mediate between entrepreneur’s gender and business performance? Do women- and men-led businesses significantly differ in terms of (financial and operational) business performance resulting from their innovations?

To answer these research questions, we use a quantitative and multidimensional empirical approach applied to a sample of 1376 Spanish SMEs, drawn from an innovation survey carried out in 2012 to businesses in manufacturing, construction, commercial and services sectors. This large number of businesses allow us to compare the introduction of innovations and different performance measures of men- versus women-led businesses. In addition, the survey has the advantage of including information regarding individual traits of the entrepreneur, such as age, tolerance to risky projects, confidence in own abilities and skills, and education level, which are factors likely to influence firms’ performance (Fairlie & Robb, 2009; Kiefer et al., 2022; Lemma et al., 2022; Marlow & McAdam, 2013). Our dataset is interesting because, despite its advance toward gender balance in many aspects of society, Spain still lags behind many European countries in terms of gender equality regarding labour and economic participation (World Economic Forum, 2021).Footnote 2 In addition, SMEs play a significant role in Spain in creating employment and value added (European Commission, 2018).

We follow the empirical approach of Baron and Kenny (1986) to mediation in order to explore whether the introduction of innovations mediate in the link between entrepreneur’s gender and firms’ performance. In line with the work of Expósito and Sanchis-Llopis (2018), we consider that the innovation-performance relationship is multi-dimensional and depends upon the innovation type and the performance indicator analysed. In line with the definition of the OECD, three types of innovations (new product or service, new process and organisational innovations), will be considered to characterise the innovation profile of the firm (OECD, 2010). Technological innovations, such as new products/services and new methods of production, are usually the result of technological change to develop or improve products, services and production methods (Freeman, 1974). Alternatively, organisational innovations are generally associated with non-technological changes affecting the business organisational and administrative dimensions (Camisón & Villar-López, 2014; Walker et al., 2015), and have been less explored in the literature. Regarding business performance, we analyse two dimensions, namely, financial and operational performance, and we use two indicators to capture each dimension. Financial performance is measured using indicators of increase in sales and reduction in costs, whilst operational performance is measured using indicators regarding the quality improvement of the products/services offered, and an increase in production capacity. Our multi-dimensional approach then allows us to undertake a fine-grained analysis on the role of entrepreneur’s gender on the introduction of different innovations types, and on the effect of each type of innovation on the different performance dimensions.

Our empirical findings show that SMEs led by men entrepreneurs are more likely to implement process innovations, in comparison to those run by women entrepreneurs, and that process innovations have a positive impact on financial and operational performance. In addition, our findings show that men-led and women-led SMEs are similar regarding their probability to introduce product and organisational innovations, and that these two types of innovations affect positively SMEs’ performance. Thus, our study provides empirical evidence that gender matters mainly in that women entrepreneurs differ with respect to the type of innovations they tend to introduce, which, in turn, has an impact on the different businesses’ performance dimensions.

The main contributions of this research are as follows. First, despite the increasing academic and practical interest in gender and entrepreneurial issues, the issue of how the entrepreneurs’ gender may affect SMEs performance has not been sufficiently addressed. We extend existing empirical literature in the gender and entrepreneurship research field by using a quantitative and multi-dimensional approach to analyse the effect of entrepreneur’s gender on business performance, for a large sample of Spanish SMEs. Second, earlier works have studied the relationship between entrepreneur’s gender and business performance, assuming that it is a straight-forward direct relationship. Instead, we examine how gender affects business performance through the introduction of innovations. Following the mediation approach of Baron and Kenny (1986), we suggest and test a parsimonious mediation model to explore whether innovations mediate in the relationship between entrepreneur’ gender and firms’ performance. Previous studies have analysed mediating effects of different factors on this relationship. For instance, for a sample new ventures in Korea, Lee and Marvel (2014) analyse the mediating role of firms’ assets, industry and location on the link between owners’ gender and business performance (measured as sales and exports), and Lee et al. (2016) explore how R&D expenditures mediate the gender-performance relationship (also measured as sales and exports). However, no study has undertaken a multi-dimensional research on entrepreneur gender-innovation-performance relationship for a large sample of established SMEs, so that this is the first empirical study on the mediating role of innovations on the relationship between entrepreneur’s gender and business performance.

The article is organised as follows. In the next section, we review the main literature on entrepreneur gender and innovation-performance relationship, and we also establish our main research hypotheses. The “Data, Variables and Descriptive Statistics” section presents the data and descriptive statistics. The “Model Specification and Results” section describes the empirical methodology and reports the estimation results and their discussion. Finally, the “Conclusions” section presents the concluding remarks.

Related Literature and Hypotheses

We use insights from different strands of the literature related to the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm, together with feminist theories and gendered institutions theory, with the aim to explore how the link between entrepreneurs’ gender and business performance may be mediated by the introduction of innovations within the firm. The literature exploring the relationship between entrepreneur gender and firm’s performance is extensive. Though several studies have reported underperformance of women entrepreneurs, compared to men (Ali & Shabir, 2017; Fairlie & Robb, 2009; Kiefer et al., 2022; Lemma et al., 2022), other studies have shown that the differences in performance by gender disappear once a number of business characteristics are considered, such as human capital, risk aversion and business and sector characteristics, amongst others (Du Rietz & Henrekson, 2000; Johnsen & McMahon, 2005; Khalife & Chalouhi, 2013; Robb & Watson, 2012; Watson, 2002). A recent literature review can be found in Coleman (2016), who documents that empirical evidence is inconclusive as to whether manager’s gender plays a role on business performance, and on which indicators are appropriate for measuring performance. Despite the existence of this extensive literature, the mediating effects of other factors, such as innovativeness of the firm, on the relationship between entrepreneur’s gender and business performance needs further research (Lee et al., 2016). This work aims to close this gap in the existing literature.

According to the RBV (Barney, 1991), business performance depends on the firms’ resources (e.g., human capital or financial capital), and also on the individual resources or skills of their decision-makers in using these resources (Álvarez & Busenitz, 2001; Barney, 1991; Wang et al., 2016; Wernerfelt, 1984). Within this strand of the literature, the role of the entrepreneur’s gender as a factor that may influence the use of resources (including innovation activities) to improve business performance has also been insufficiently analysed.

In addition, social constructionist feminist theories suggest that cultural factors and norms, upbringing and social interactions explain disparities amongst men and women in society (Ahl, 2006). These theories consider that gender is determined by the societal structure, leading to stereotypes on men and women abilities, behavioural patterns and skills, including those related to the development of innovations and performance achievements within the firm, to women disadvantage (Laguía et al., 2019; Wieland et al., 2019). Furthermore, the theory of gendered institutions (Acker, 1992) states that female entrepreneurs are at disadvantage regarding the access to crucial resources for innovation and business performance, such as financial, human and social capital resources (Van Staveren, 2013). According to this theory, women entrepreneurs are also at disadvantage regarding their access to informal networks (Estrin & Mickiwictz, 2011; Kelley et al., 2011) and they lack required financial, human and social capital to ensure the development of innovation capabilities, in comparison to their male counterparts (Carter et al., 2007; Orser et al., 2006), what may imply higher constraints for women entrepreneurs to successfully run their businesses and obtain high performance (Bardasi et al., 2011).

With the aim to set our research hypotheses, the following subsections are organised as follows. Firstly, a brief literature summary on the relationship between entrepreneur’s gender and firm’s innovativeness is provided to investigate if SMEs managed by men entrepreneurs show a higher innovativeness than those managed by women. Secondly, the relationship between innovativeness and business performance is explored based on the current evidence in the literature and leading to our second research hypothesis. Lastly, the hypothesis on the mediating effect of firm’s innovativeness on the relationship between entrepreneur’s gender and business performance is presented.

Entrepreneur Gender and Firm’s Innovativeness

An increasing literature points out that the innovation profile of a company is affected by the entrepreneur’s gender, amongst other factors (see Arun & Rojers, 2021 for a review of the literature). Specifically, some of these works have documented significant disparities between male and female entrepreneurs that could explain different propensities to undertake innovation decisions (Alsos et al., 2013; Arun & Rojers, 2021). In this same line, Weber and Geneste (2014) documented that female entrepreneurs were less concerned with the development and implementation of innovations in their firms and with the achievement of high financial performance due to the associated risks and the resources needed for innovation. As reported by Pelger (2012) and Orser and Riding (2018), female entrepreneurs have different preferences and therefore different goals compared to male entrepreneurs, and these differences are significant in explaining the lower interest in innovation and technology adoption. In a recent study on the strategies implemented by Italian entrepreneurs to cope with the economic crisis, Buratti et al. (2018) have acknowledged that, in comparison to men entrepreneurs, women are less prone to adopt offensive strategies (like innovation, development or growth), and more prone to embrace a defensive approach (restructuring and resizing strategies). The work of Foss et al. (2013) argues that though female and male entrepreneurs are equal in generating new ideas and innovations, those coming from women would be less implemented in the firm.

Some explanations have been discussed in the literature to shed some light on the entrepreneur’s gender gap regarding the innovation profile of the firm. One of these plausible explanations would derive from stereotyping masculine versus feminine groups from informal gendered institutions, as firstly argued by Agarwal (1997). In addition, gender differences in the entrepreneur’s education background may also explain these uneven innovative propensities between men and women entrepreneurs (Walters & McNeely, 2010). Furthermore, women entrepreneurs would also face limitations to access to crucial financial resources and to the advantages provided by extensive business networks (Estrin & Mickwictz, 2011; Kelley et al., 2011). The work of Audretsch et al. (2022) highlights that access to financial resources and the institutional environment are crucial factors to spur innovation activities in women-led businesses.

Regarding the types of innovation, the impact of entrepreneur’s gender has recently been analysed not only regarding technological innovations, that is, product innovation (Pablo-Martí et al., 2014; Protogerou et al., 2017) and process innovations (Faems & Subramanian, 2013; Fernández, 2015), but also in relation to non-technological innovations, such as organisational innovations (Heyden et al., 2018; Lyngsie & Foss, 2017). Nevertheless, few studies have analysed both types of innovations simultaneously in a multi-sector sample of firms. Dohse et al. (2019) and Zastempowski and Cyfert (2021) show that male managers are more prone to implement product innovations. Conversely, Na and Shin (2019) provide evidence that gender does not affect the probability to introduce any type of innovation. In addition, a majority of studies have analysed technological innovations in manufacturing and high-technology sectors, thus ignoring innovation in services and other women-oriented sectors (Alsos et al., 2013; Nählinder et al., 2012; Pettersson & Lindberg, 2013). The work of Expósito et al. (2021), that considers both technological and non-technological innovation types, along with all business sectors, does not find significant differences in the propensity of men- and women-led businesses to introduce innovations of new products and new forms of organisation in the firm, once they control for personal traits and business characteristics. However, they observed a significantly greater propensity of men entrepreneurs to implement process innovations, in comparison to women entrepreneurs. In a similar line of research, the work of Strohmeyer et al. (2017), for a survey sample of German entrepreneurs, shows that women-led businesses display less technological innovativeness, in comparison to those firms led by men. In summary, a number of studies have documented the existence of significant gender differences amongst entrepreneurs as regards firm’s innovativeness. Based on this literature, the following hypothesis is presented:

Hypothesis 1. SMEs managed by men entrepreneurs show a higher innovativeness than those managed by women.

This hypothesis will be tested for product, process and organisational innovations.

Innovativeness and Business Performance

Firm innovativeness constitutes an extremely important factor in explaining business competitive advantage and performance. The literature in this field is extensive, both in developed and developing economies (Buratti et al., 2018; Hashi & Stojčić, 2013; Lichtenthaler, 2016; Love & Roper, 2015; Mahmutaj & Krasniqi, 2020; Ramadani et al., 2017). Firms’ innovativeness may help to enjoy first-mover advantages in the markets, enhancing business performance on different indicators, such as sales, costs and profitability. By implementing innovations, firms may achieve enhanced production efficiency through reducing operational costs, technological upgrading and greater economies of scale by augmenting production capacity (Lee et al., 2016). Additionally, greater innovativeness may help SMEs to diversify the portfolio of products and services (product innovation), as well as to increase their quality, leading to the development of product market differentiation strategies and better business performance.

Regarding the financial dimension of performance, several studies found evidence on the positive effect of innovations on financial indicators, such as sales and production costs, thanks to an improvement in labour productivity and business efficiency (Añón-Higón et al., 2015; Foreman-Peck, 2013; Máñez et al., 2013; Rochina-Barrachina et al., 2010). As regards the type of innovation implemented, some studies show that product and process innovations have a positive effect on reducing costs of production (Hall et al., 2009) and on increasing financial turnover in SMEs (Foreman-Peck, 2013). Studies such as Añón-Higón et al. (2015) and Hervás-Oliver et al. (2014) confirm these findings for Spanish SMEs. The study of Hervás-Oliver et al. (2014) also finds a positive effect of organisational innovation on SMEs’ financial performance. Conversely, other works do not confirm these positive impacts. In fact, Freel and Robson (2004) and Hall (2011) state that product and process innovations might negatively impact sales growth and productivity in SMEs, as shown by empirical evidence in the case of Scotland (UK). These empirical results are also established by Jaumandreu and Mairesse (2016) who provide evidence on the cost increase caused by product innovation. Finally, regarding organisation innovation, and though the literature on this type of innovation is scanter, its impact on sales increase would be positive, as argued by Lin and Chen (2007) and Expósito and Sanchis-Llopis (2020).

The literature investigating the impact of innovations on the operational dimension of SMEs performance is scarcer since most of the studies have usually focused on performance financial indicators, such as sales growth, productivity, turnover and costs. In this study, we consider two indicators regarding the operational dimension of business performance that is quality enhancement of products/services provided by the firm and increase in the firm’s productive capacity. Amongst the scant works analysing the effect of innovation on quality enhancement, we should highlight the following. The study of Prajogo et al. (2013) asserts that improvement of quality features in products and services offered by the firm is significantly determined by the innovation profile of the firm. In a similar line, López-Mielgo et al. (2009) and Saunila (2016) argue that a continuous improvement of product quality requires strong innovation capabilities of the firm. Along these lines, research works such as Scarbrough et al. (2015) and Prajogo et al. (2013) discuss that process and organisational innovations foster new forms of managerial practices that generally lead to quality improvements in goods and services.

The analysis of the effect of innovations on production growth has traditionally focused on financial indicators, such as sales growth. Nevertheless, sales do not necessarily reflect an operational transformation of the firm as regards, for example, a higher number of employees and/or greater productive capacity. Though growth in relation to employment generation has attracted some interest in the literature on innovation (see, for example, Harrison et al., 2014; Triguero et al., 2014), the plausible effect of innovation on augmenting the productive capacity of the firm (and thus, increasing its employment and investment levels) has not received sufficient attention. Our study follows the work of Expósito and Sanchis-Llopis (2018) by considering a multidimensional analytical framework with multiple types of innovations and business performance measures (financial and operational). Thus, we present the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. Innovativeness asserts a positive impact on financial and operational business performance.

This hypothesis will be tested for product, process and organisational innovations, and for two indicators of financial performance (sales increase and cost reduction), and two indicators of operational performance (increase of productive capacity and quality improvement).

Indirect Impact of Entrepreneur Gender on Business Performance

The influence of entrepreneur’s gender on business performance has been extensively analysed in the last decade (see, e.g., Kiefer et al., 2022, and references therein). Particularly, the role of gender has been analysed regarding potential differences in business costs (Watson, 2002), employment and labour productivity (Ali & Shabir, 2017; Chirwa, 2008; Menzies et al., 2004; Rosa et al., 1996); revenue and profitability (Du Rietz & Henrekson, 2000; Menzies et al., 2004); capacity utilisation (Ali & Shabir, 2017) and business survival (Boden & Nucci, 2000; Robb & Watson, 2012; Basyith & Idris, 2014). Despite this wide range of studies, empirical evidence on the role played by entrepreneur’s gender on business performance remains inconclusive (Coleman, 2016). Additionally, most of these studies analyse the direct impact of entrepreneur’s gender on business performance, so that the potential mediation effects of other factors, such as firm’s innovativeness in the relationship between gender and performance have not received a sufficient attention in the existing literature (Lee et al., 2016).

Following the mediation framework of Baron and Kenny (1986), our previous hypotheses postulate that entrepreneur’s gender directly affects firm’ innovativeness, as measured by the probabilities to introduce product, process and/or organisational innovations, which, in turn, also directly affect the business performance in its two dimensions, financial and operational. As a result, entrepreneur’s gender could indirectly affect business performance through firms’ innovativeness. According to the RBV of firms (Barney, 1991), the availability of resources and capabilities by the firm, such as capability to implement innovations, is crucial to business performance. Additionally, this theory also argues that personal features of the entrepreneur, such as gender, should be considered since they might determine the firm’s capabilities (Álvarez & Busenitz, 2001; Wang et al., 2016). In this regard, the theory of gendered institutions (Acker, 1992) states that women entrepreneurs are at disadvantage compared to men regarding the access to those unique resources (e.g., financial, human and social capital resources) that are needed to develop innovations, so that they may be less able to succeed in terms of achieving certain performance goals (Lee et al., 2016). In this regard, and as suggested by the theory of gendered institutions, there might be an underlying mediating link between entrepreneur’s gender and business performance. With this theoretical framework in mind, we aim to test the next hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3. The relationship between entrepreneur’s gender and business performance is mediated by firm’s innovativeness.

Similarly to previous hypotheses, firm’ innovativeness is measured by the introduction of product, process and/or organisation innovations, and business performance takes into account two dimensions, financial (that is, sales increase and cost reduction) and operational (that is, increase of productive capacity and quality improvement of product/services).

Figure 1 represents our theoretical framework and hypotheses to be tested.

Data, Variables and Descriptive Statistics

The data we analysed come from a survey on a sample of Spanish SMEs, undertaken in 2012 and designed to include only companies with less than 250 employees and sales below €50 million annually. Self-employed entrepreneurs without employees are not included in the survey. Although the data were gathered in 2012, we must note that the composition of Spanish SMEs is similar to the recent years, both in terms of sectors and innovativeness orientation.Footnote 3 This survey was financed by the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness of Spain, together with some Spanish regional governmental agencies. The survey collects information for six Spanish regions, Navarre and Basque Country, Andalucía, Extremadura, Madrid and Murcia, representing the northern, southern and central regions of the country.Footnote 4

The dataset is composed of a total of 1424 SMEs. Since our focus is on the comparison of men- and women-led SMEs, in our analysis, we exclude nascent businesses and consider only those businesses with at least three years of experience in the market. The reason is that female entrepreneurs usually face greater obstacles during the setup stage of the firm. Hence, our final sample includes 1376 SMEs, out of which 969 businesses (70,42%) are run by a male entrepreneur, and 407 businesses (29,58%) are run by a female entrepreneur.

The survey contained information regarding the introduction of innovations and the impact of innovations on several dimensions of business performance. The questionnaire also included information on a number of personal traits of the entrepreneur, and on characteristics and strategies of the business. The survey was answered by the entrepreneur, defined as the person performing the main managerial functions within the business. There is empirical evidence documenting that entrepreneurs are responsible of the most significant decisions within their businesses, including innovation strategies (Alegrem et al., 2011; Donate & de Pablo, 2015; Van Gills, 2005). In addition, several studies indicate that self-reported information by entrepreneurs may be considered an appropriate method to analyse firms’ strategies and performance (Foreman-Peck, 2013; Goya et al., 2016; Ribau et al., 2017).

We measure firms’ performance using information provided by the entrepreneurs on whether they consider that innovations implemented in the previous three years have had a considerable impact on business performance, distinguishing between financial performance (cost reduction and increase in sales) and operational performance (quality improvement of products/services and increase in production capacity). Regarding innovations, the survey provides information on product, process and organisational innovations implemented by the business during the previous three years, and considered new or significantly improved innovations. Using this information, we create three binary indicators on whether or not each innovation type has been introduced in the business.

In our analysis, the key independent variable is entrepreneur’s gender. The survey provides information on the gender of the major decision-maker of the SME, or entrepreneur, who is the person in charge of answering the questionnaire. From this information we construct a dichotomous variable that takes value one when the entrepreneur is a man, and zero when the entrepreneur is a woman.

In our empirical analysis, we also consider a number of covariates that may be relevant for our analysis. We group these control variables into three classes: entrepreneurial traits, business characteristics and strategies, and business environment determinants. In relation to entrepreneurial traits, apart from gender, we consider risk tolerance, self-confidence, age and education. There is evidence that these variables play a role in explaining SME performance (Ben Slimane et al., 2022; Entrialgo, 2002; Kraus et al., 2012; Martínez-Roman & Romero, 2017; Millán et al., 2021; Saunila, 2016; Van Stel et al., 2021). Regarding businesses characteristics, we consider first business size and age, which have been extensively analysed in the literature as determinants of SMEs performance (Goya et al., 2016; Hall et al., 2009; Rosenbusch et al., 2011). We also control for business strategies, such as involvement in collaborative R&D activities, which includes cooperation with other businesses and with public institutions. These collaborative strategies are aimed at sharing the risk associated with innovation and may have a positive effect on performance (Greco et al., 2015; Vahter et al., 2013; Vásquez-Urriago et al., 2016). We also include a variable capturing whether the firm participates in business trade fairs and exhibitions, which may be considered an activity to promote both collaboration and firms’ products/services. Last, we also include whether the SME participates in exporting and importing activities, which may be positively associated with business performance (Love & Roper, 2015; Oura et al., 2016). Finally, we control for the business environment where the SME operates. In particular, we introduce regional and industry dummies to account for differences in technology across sectors, and in business regulations and policies amongst regions. See Table 7 in Appendix for a description of all variables used in our analysis.

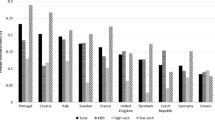

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the SMEs in our sample, including the mean and standard deviation of the variables we introduce in our empirical study, and differentiating between those companies led by a man entrepreneur (70.42%) and those led by a woman entrepreneur (29.58%). As regards to business performance measures, we observe that men-led SMEs are more likely to report cost reductions (46.13%), in comparison to women-led SMEs (40.29%), being this difference statistically significant. In addition, the other three measures of performance are also higher for businesses run by male entrepreneurs than for businesses run by women, although the differences are not statistically significant. Regarding innovations, we observe that men entrepreneurs are more likely to implement process innovations (30.44%), in comparison to women counterparts (22.35%), and this difference is statistically significant. We further notice that product innovations are the type of innovation more common to be introduced by both men and women entrepreneur (54.59% and 56.02%, respectively), followed by organisational innovations, which are introduced by 32.50% and 32.43% of men and women entrepreneurs, respectively. Turning to entrepreneurial traits, there are statistically significant differences between men and women entrepreneurs regarding age and education: male entrepreneurs are 48 years old, on average, whereas this figure is 44 for female entrepreneurs; a higher proportion of men entrepreneurs report only primary education, and a higher percentage of women entrepreneurs hold tertiary education. Finally, regarding differences in business characteristics and strategies, SMEs run by female entrepreneurs are on average smaller, younger, and belong to the services sector in a higher proportion, whereas SMEs led by men entrepreneurs show a greater participation in business trade fairs and a higher propensity to import from foreign markets.

In Table 2, we present the Pearson correlation matrix to test for multicollinearity. As it may be inspected, all the pairs of variables correlations are low and not significant. We observe that the correlation coefficients are all lower than 0.8, so we may conclude that we do not have a concern for multicollinearity in our study. In Table 2, we report the variance inflation factor (VIF) test, indicating that our results are not biassed due to multicollinearity since all the values are around or lower than 2.

Model Specification and Results

Model Specification

To test Hypothesis 1, we jointly investigate the three innovation decisions (implementing new products into the market, new processes of production, and organisational innovations), since the entrepreneur may consider to introduce together the three types of innovations. To perform this analysis, we use a multivariate probit model that allow concurrent innovation decisions by the entrepreneur. The specific model we use is a trivariate probit that allows estimating the joint probability to implement the three types of innovations. Thus, we estimate a trivariate discrete choice model, as follows:

where the subscript i is and indicator of the SME. We use three dichotomous variables as dependent variables. Each of these variables takes value one when the entrepreneur states to have implemented product, process and organisational innovations, respectively, in the previous three years, and zero otherwise. X1i is a vector of variables accounting for personal traits of the entrepreneur (gender, tolerance to risky projects, self-confidence, age and education). X2i is a vector of firms’ characteristics that may influence the decision to innovate, such as size, age, R&D cooperation, participation in business exhibitions, industry and region. Finally, εi is an error term.

The multivariate specification we use will permit systematic correlations amongst the choices of the different innovations.Footnote 5 The rationale for this is that there might be complementarities or substitutabilities amongst the three types of innovation. Should we find that there are significant correlations amongst the three strategies, then estimating three distinct probit models for each of the three innovation types would be inefficient. The estimation of our model is undertaken through the simulated maximum-likelihood three-equation probit model using the Geweke-Hajivassiliou-Keane (GHK) smooth recursive simulator to compute the maximum likelihood.

To test Hypotheses 2, we estimate bivariate probit models for the two financial performance measures, on the one hand, and for the two operational business performance measures, on the other hand. It is sensible to assume that implementing product, process and organisational innovations will probably affect the business’s sales and/or on its costs. Similarly, as regards the operational performance measures, innovation will probably impact the productive capacity of the company and/or on the quality of products/services of the firm. We account for the potential correlation between each of the two financial performance measures (sales increase and cost reduction) and between the two operational performance measures (productive capacity increase and quality improvement). Thus, the model to be estimated for the financial performance is the following,

where subscripts s and c in the right-hand side denote sales increase and cost reduction, respectively. The dependent variables are sales increase and cost reduction, corresponding to two binary variables taking value one when the firm states sales increase and cost reduction, respectively, and value cero otherwise. Furthermore, the variables prod, proc and org are binary variables indicating whether firm i has implemented product innovations, process innovations and organisational innovations, in the previous three years, respectively. In each specification, we also introduce two set of control variables capturing entrepreneur traits, X1i, and business characteristics and strategies, X2i; finally, εi is an error term.

Similarly, the bivariate probit model for the two operational performance measures is,

where subscripts ca and q in the right-hand side denote capacity increase and quality improvement, respectively. The variables capacity increase and quality improvement are the dependent variables, corresponding to two binary variables taking value one when the firm states an increase in production capacity, and an improvement in que quality of its products, respectively, and value cero otherwise. The variables prod, proc and org are binary variables indicating whether firm i has implemented product innovations, process innovations and organisational innovations, in the previous three years, respectively. In each specification, we also introduce two sets of control variables capturing entrepreneur traits, X1i; and business characteristics and strategies, X2i; finally, εi is an error term.

Estimation Results

The findings of our estimations are presented in this section. Following our conceptual approach, we test whether the gender of the decision-maker indirectly impacts on performance through the introduction of innovations. In particular, we test whether innovations (product, process and organisational innovations) mediate between entrepreneur’s gender and business (financial and operational) performance. For mediation effects to exist between the gender of the entrepreneur and business performance, four conditions must be met (Baron & Kenny, 1986). First, the gender of the entrepreneur should significantly affect the mediators (in our case, product, process and organisational innovations). Second, the mediators should have a significant impact on business performance. Third, entrepreneur’s gender should significantly affect performance. And fourth, when both the entrepreneur’s gender and the mediators are included in the same regression, the effect of gender on performance should become insignificant (full mediation) or the size of its coefficient should diminish (partial mediation), in comparison to the coefficient estimated without the mediators. If empirical results meet these four criteria, they support mediation effects, through the introduction of innovations, between the gender of the entrepreneur and SMEs performance.

The first condition for mediation to hold is that the entrepreneur’s gender must have a direct effect on (product, process and organisational) innovations, and this condition corresponds to testing Hypothesis 1, stating that SMEs led by men entrepreneurs have a higher probability of introducing innovations, compared to women. To test for Hypothesis 1, we implement a trivariate probit model to estimate the joint probabilities of introducing product, process and organisational innovations, as given by Eq. (2).

The results of the trivariate probit model for the joint decision to introduce new products, new processes and organisational innovations are presented in Table 3.Footnote 6 The coefficients for the covariates estimated differ noticeably for the three equations, showing that the three innovative choices are heterogeneous. These findings are in line with the works of Carboni and Russu (2018) and Doran (2012), who revealed the existence of complementarities amongst the three types of innovations using data for European and Irish companies, respectively.

Results in Table 3 reveal that gender exerts a positive and statistically significant impact on the decision to introduce process innovations, but it has no impact on the other two decisions (implementing a product or organisational innovation). Hence, our results indicate that SMEs run by men are more likely to implement process innovations in comparison to firms led by women. In addition, we obtain that gender does not influence the prospect of implementing product and organisational innovations, so that men and women entrepreneurs are equally likely to introduce these two types of innovations. Hence these results support Hypothesis 1 only regarding process innovations, so that the first condition for mediation only holds for this type of innovation. These results reinforce previous findings reporting that men entrepreneurs are more likely to implement process innovations (Expósito et al., 2021), and are in line with Strohmeyer et al. (2017), who show that German women entrepreneurs reveal less technological innovativeness, in comparison to men entrepreneurs. This finding is consistent with feminist theories, such as social and constructionist feminist theories, which claim that gender is a socialisation concept that influences managerial behaviour, so that gender differences in process innovations would persist after controlling for differences in managerial and business attributes. Our findings are only partially consistent with those of Na and Shin (2019), who found that female top managers are not significantly more likely to implement product, process or organisational innovations, using a cross-country data set from emerging countries. Furthermore, our findings contradict Dohse et al. (2019) and Zastempowski and Cyfert (2021) findings that female managers are more likely to implement product innovations.

Other managerial attributes uncover different effects on the firm’s propensity to introduce innovations. A high tolerance for risky projects has a positive and significant impact on the likelihood of implementing product and organisational innovations, whereas a high level of self-confidence in managerial skills increases the likelihood of implementing product innovations. The propensity to introduce the three categories of innovations decreases significantly with the age of the entrepreneur. Secondary and tertiary education enhances the likelihood of implementing organisational innovations, but it has no impact on the likelihood of implementing product or process innovations. Regarding business characteristics, being a small SME (10–50 employees), compared to being a microbusiness (the benchmark category, with up to 10 employees) is positively associated with innovativeness. In addition, both R&D cooperation and attending businesses exhibitions have a positive impact on the implementation of both product and process innovations.

We now turn to the analysis of the second condition that needs to hold for mediation, that is, whether there is a direct impact of innovations on (financial and operational) performance. This second condition corresponds to testing for Hypothesis 2, stating that the introduction of innovations affects positively to financial and operational business performance. In Table 4, we present the bivariate probit results for financial and operational performance given by Eq. (3) above.

Estimating results of Table 4 show the direct impact of the three types of innovations on both financial and operational performance. Columns (1) and (2) report the bivariate probit estimates for the two indicators of financial performance, namely, cost reduction and sales increase. These are jointly estimated to capture the possible correlation between them. In addition, columns (3) and (4) report the bivariate probit estimates of the two indicators of operational performance, namely, quality improvement and capacity increase, which are also jointly estimated.Footnote 7

Regarding business financial performance (columns 1 and 2), results show that both introducing process and organisational innovations in the previous three years increases the probability of cost reduction, and that product and organisational innovations implemented during the previous three years increase the probability of experiencing a sales increase. As for the impact of innovations on operational performance (columns 3 and 4), our results indicate that the three types of innovations implemented by the firm in the last three years have a positive and significant impact on both quality improvement and capacity increase. Therefore, these finding provide empirical support to our Hypothesis 2, and indicate that the second condition for the mediation to hold is satisfied, that is, the mediators (product, process and organisational innovations) show a significant effect on business performance.

The rest of covariates in Table 4 indicate that managerial traits, such as risk tolerance and self-confidence are positively associated with both financial and operational business performance, whereas the age of the entrepreneur shows a negative impact on both dimensions of performance. Regarding business characteristics, being a small business is positively associated with cost reduction, whereas medium businesses are positively linked to capacity increase. R&D cooperation with other businesses is positively related to cost reduction, quality improvement and capacity increase, and R&D cooperation with public institutions is related to sales increase. Finally, being an exporting firm is also positively associated with both financial and operational performance.

The third and fourth condition of Baron and Kenny (1986) for mediation to hold corresponds to testing Hypothesis 3, stating that the link between entrepreneur’s gender and business performance is mediated by the introduction of innovations. Tables 5 and 6 present the bivariate probit estimating results for financial and operational business performance, respectively, considering the role of entrepreneur’s gender.

Previously to explaining the results, it is important noticing that in Tables 5 and 6, we report the tests of correlation between the two indicators. In particular, in Table 5, we report the test for the correlation of the two financial performance indicators (increase of sales and cost reduction), and in Table 6, the correlation test for the two operational performance indicators (expansion of productive capacity and enhancement in quality). In all cases, the null hypothesis of no correlation is rejected, indicating that both indicators in each performance measure are correlated, and therefore, that joint estimations are appropriate (the results for these tests are reported at the bottom of the corresponding table).

Table 5 reports the results regarding financial performance. Columns (1) and (2) show the effect of gender on the two indicators of financial performance, namely, cost reduction and sales increase. Results show that gender positively affects cost reduction but has no impact on sales increase. Hence, the third condition for mediation holds only for cost reduction: the gender of the entrepreneur positively and significantly affects cost reduction, so that those firms led by men show a higher probability to reduce costs as a result of innovation, compared to women-led firms. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 5 include both the gender of the entrepreneur and the three types of innovations (the mediators). Regarding the impact of gender, we observe that the size of its coefficient for cost reduction is reduced, compared to the estimation without the mediators, indicating that the fourth condition for mediation holds, so that a partial mediation effect for process innovation is found. Hence, regarding financial performance, our empirical results satisfy the four conditions for mediation in the case of process innovations and the cost indicator. Consequently, our findings show that the introduction of process innovations partially mediates the relation between entrepreneur’s gender and business cost reduction (the coefficient of gender is reduced). To test for the partial mediation effect, we have decomposed the gender effect in the cost reduction specification (column 3 in Table 5) into the direct and indirect effects using the KHB-method developed by Karlson et al. (2011) and Breen et al. (2013).Footnote 8We obtain that the total effect amounts to 0.158, being the direct effect 0.145 and the indirect effect (through the mediation variables) 0.012 (with a p-value of 0.052). This mediating effect represents 7.7% of the total effect.Footnote 9 The impact of the rest of covariates in Table 5 regarding entrepreneurial and business traits on the two indicators of financial performance is similar to those reported in columns (1) and (2) of Table 4.

Table 6 presents the estimates of the bivariate probit estimates for operational performance. Columns (1) and (2) show the impact of gender on the two indicators of operational performance, namely, quality improvement and capacity increase. Results show that gender positively affects both indicators of operational performance, so that those firms led by men show a higher probability to enhance the quality of their products/services and to expand their capacity of production derived from innovation introduced by the firm, compared to women-led counterparts. Hence, the third condition for mediation holds.

Columns (3) and (4) of Table 6 include both the gender of the entrepreneur and the three types of innovations (the mediators). Regarding the impact of gender, we observe that the size of its coefficient for quality improvement is reduced, and that the coefficient for capacity increase becomes insignificant, compared to the estimation without the mediators, indicating that the fourth condition for mediation holds. Hence, our results show that a partial mediation effect for the introduction of process innovations is found in the case of quality improvement. As before, we use the KHB method to decompose the gender effect into the direct and indirect effects for the quality improvement specification (column 3 in Table 6). The total effect in this specification amounts to 0.157, being the direct effect 0.145 and the indirect effect (through the mediation variables) 0.012 (with a p-value of 0.110). This mediating effect represents 7.6% of the total effect. In the case of capacity increase, our results show a full mediation effect for the introduction of process innovation. In the decomposition of the gender effect for the capacity increase specification (column 4 in Table 6), the total effect amounts to 0.130, being the direct effect 0.116 (and not statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.196) and the indirect effect (through the mediation variables) 0.014 (with a p-value of 0.018). This mediating effect represents 10.77% of the total effect. These results then confirm the full mediation effect of process innovations regarding capacity increase.

Therefore, regarding operational performance, our empirical results also satisfy the four conditions for mediation in the case of process innovations, that is, our findings reveal that the introduction of process innovations partially mediate the relation between entrepreneur’s gender and business quality improvement (the size of the coefficient of gender is reduced, although it is still significant), and fully mediate the relation between entrepreneur’s gender and capacity increase (the coefficient of gender becomes insignificant). The influence of the rest of covariates in Table 6 regarding entrepreneurial traits and business characteristics on the two indicators of operational performance is similar to those presented in columns (3) and (4) of Table 4.

Results in Tables 5 and 6 show that the effect of innovativeness on business performance should be investigated using a multi-dimensional approach, as indicated by other works, such as Expósito and Sanchis-Llopis (2018), Damanpour et al. (1989), Edwards et al. (2005) and Wolff and Pett (2006).

Finally, we undertake some supplementary analyses to demonstrate that the findings reported are robust to alternative sample selection of SMEs, and to expanding our specifications with other control variables. First, our findings are also robust to another sample selection of firms. We undertake our empirical analysis including in the sample not only established SMEs (firms active in the market for at least three years) but also nascent SMEs. These new-born businesses have to overcome the obstacles related to the setup stage, which may be tougher for women entrepreneurs, as already acknowledged in other works (Koellinger et al., 2013). When using this broader sample of SMEs, we obtain similar results, so that our empirical estimates are robust to also incorporating nascent SMEs. Second, the robustness of our estimates has been also tested by expanding the control variables in our specifications. The consideration of additional characteristics of the business, like a dichotomous variable accounting for the ownership structure of the SME as a limited liability company, and a dichotomous variable accounting for being part of a corporate group rendered non-significant estimates, thus not changing the above findings.

Conclusions

The relationship between entrepreneur’s gender and firm’s performance has been analysed in related literature assuming that it is a straight-forward direct relationship. Instead, in this study we have investigated how gender affects business performance indirectly through the introduction of innovations. In particular, following the mediation approach of Baron and Kenny (1986), we have established and tested a parsimonious mediation model to explore whether the introduction of innovations mediate in the relationship between entrepreneur’s gender and firms’ performance. We therefore have explored differences between men-led and women-led businesses as regards the performance results they obtain from innovating. This approach is novel and constitutes the main contribution of our study to existing literature. In addition, most of the works analysing the role of entrepreneur’s gender on business performance are qualitative in nature and focus on the personal attributes of the entrepreneur. Instead, we provide new empirical evidence using a quantitative and multi-dimensional approach differentiating between innovation types and business performance indicators for a large sample of Spanish SMEs. Hence, our study adds to the management and business literature using a multilevel approach to the analysis of the determinants of business performance.

Our study provides empirical evidence that gender matters mainly in that women entrepreneurs differ with respect to the type of innovations they tend to introduce, which, in turn, has an impact on business performance. In particular, our empirical findings show that SMEs led by male entrepreneurs are more likely to introduce process innovations, in comparison to SMEs run by women, and that process innovations have a positive effect on financial and operational performance. Hence, our results indicate that men-led SMEs achieve superior performance from their higher propensity to implement process innovations, in comparison to women-led SMEs.

These findings suggest the need to incorporate a gender perspective in those policies dealing with enhancing SMEs innovativeness and performance. In particular, public policy should deal with the design of more effective policy instruments to promote process innovations by female entrepreneurs as a way to increase their business performance. Related to this, public policy should tackle gender inequality in education and workplace regarding technically oriented fields, establishing mechanisms to promote female participation in those fields, which may facilitate the implementation of process innovation by female entrepreneurs.

Finally, there are some limitations to our study that could open up new research directions. First, the data we analyse corresponds to a representative sample of Spanish SMEs, and although our findings are likely to replicate those of other developed economies, our results should be verified in the context of other countries. Second, our data is cross-sectional in nature, so that we should be cautious about the causal interpretation of our findings. Further research based on longitudinal panel data should be performed in order to verify the causal relationships exposed in this work. Third, more research is required to determine and explain why women entrepreneurs are less likely than men entrepreneurs to introduce process innovations. Lastly, we have focused only on innovation activities as mediators between entrepreneur’s gender and business performance, and have not analysed the potential mediation role of other business strategies, such as exporting and importing activities, which could be avenues of further research.

Data Availability

Data are available from authors upon reasonable request.

Notes

In the last decade, there has been an increased interest in analysing the role played by gender on firms’ innovativeness. See, amongst others, the works of Weber and Geneste (2014), Buratti et al. (2018), Marvel et al. (2015), Strohmeyer et al. (2017), Dohse et al. (2019), Na and Shin (2019), Zastempowski and Cyfert (2021), Expósito et al. (2021), and Audrestch et al. (2022). For a review of the literature, see Arun and Rojers (2021).

The sub-index of Economic Participation and Opportunity of the Global Gender Gap Report (World Economic Forum, 2021) indicates that Spain has only slightly improved during the last decade, increasing from a score of 0.65 (75th position) in 2012 up to 0.69 in 2020 (71st position), far behind other advanced European economies such as Germany, the UK and the Scandinavian countries.

Using official figures from the Spanish Ministry of Industry, Energy and Tourism (2013), we have confirmed that the distribution of the studied sample by industry and size is comparable to that at the national level in 2013 and in 2022. Information from Spain's Ministry of Industry and Innovation further supports the trend of stagnant innovation in SMEs during the last decade.

The sampling procedure was aimed at representing the regional structure of Spain, following the stratified sampling criteria of finite populations. The SMEs’ population was divided by sector, size and location to guarantee widespread coverage, and the number of businesses within strata was calculated using information from the Central Directory of Firms, provided by the Spanish National Statistics Institute. The stratified sample was representative of the SMEs’ population across the regions considered, and no bias was revealed between respondents and non-respondents.

Notice that the models do not require the three decision being indeed related, but rather allow for all potential combinations, in the sense that businesses may differ in the type of innovation implemented.

At the bottom of Table 3, we present the correlation coefficients between the different innovation choices. These coefficients are positive and statistically significant, what points to the appropriability of jointly analysing the three choices.

The tests for these correlations are presented at the bottom of Table 4, and in both cases, we reject the null hypothesis of no correlation between the two indicators, which reveals that both indicators within each performance dimension are correlated, and hence, that their joint estimation is appropriate.

We apply the KHB method using a binary probit model as the Stata khb command does not support the bivariate specification.

Regarding the specification of sales increase, we do not perform the decomposition as the coefficient corresponding to the effect of gender is not significant.

References

Acker, J. (1992). Gendering organizational theory. Classics of Organizational Theory, 6, 450–459.

Agarwal, B. (1997). “Bargaining” and gender relations: Within and beyond the household. Feminist Economics, 3(1), 1–51.

Ahl, H. (2006). Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 595–621.

Alegrem, J., Sengupta, K., & Lapiedra, R. (2011). Knowledge management and innovation performance in a high-tech SMEs industry. International Small Business Journal, 31(4), 454–470.

Ali, J., & Shabir, S. (2017). Does gender make a difference in business performance? Evidence from a large enterprise survey data of India. Gender in Management, 32(3), 218–233.

Alsos, G. A., Hytti, U., & Ljunggren, E. (2013). Gender and innovation: State of the art and a research agenda. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 236–256.

Álvarez, S. A., & Busenitz, L. W. (2001). The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. Journal of Management, 27(6), 755–775.

Añón-Higón, D., Manjón-Antolin, M., Máñez-Castillejo, J. A., & Sanchis-Llopis, J. A. (2015). Does R&D protect SMEs from the hardness of the cycle? Evidence from Spanish SMEs (1990–2009). International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(2), 361–376.

Arun, T. M., & Rojers, J. P. (2021). Gender and firm innovation - A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(2), 301–333.

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., & Brush, C. (2022). Innovation in women-led firms: An empirical analysis. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 31(1–2), 90–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2020.1843992

Bardasi, E., Sabarwal, S., & Terrell, K. (2011). How do female entrepreneurs perform? Evidence from three developing regions. Small Business Economics, 37(4), 417–441.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Barrientos-Marín, J., Fu, N., Millán, J.M., & Van Stel, A. (2021). ICT usage at work as a way to reduce the gender earnings gap among European entrepreneurs. In E. Lechman (Ed.), Technology and Women’s Empowerment, Chapter 6, 101–118. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003045946-6.

Basyith, A., & Idris, M. (2014). The gender effect on small business enterprises’ firm performance: Evidence from Indonesia. Indian Journal of Economics and Business, 13(1), 21–39.

Ben Slimane, S., & M'henni, H. (2020). Entrepreneurship and development: Realities and future prospects. John Wiley & Sons.

Ben Slimane, S., Coeurderoy, R., & M’henni, H. (2022). Digital transformation of small and medium enterprises: A systematic literature review and an integrative framework. International Studies of Management & Organization, 52(2), 96–120.

Boden, R. J., Jr., & Nucci, A. R. (2000). On the survival prospects of men’s and women’s new business ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(4), 347–362.

Breen, R., Karlson, K. B., & Holm, A. (2013). Total, direct, and indirect effects in logit models. Sociological Methods and Research, 42(2), 164–191.

Brush, C. G., Greene, P. G., & Welter, F. (2020). The Diana project: A legacy for research on gender in entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 7–25.

Buratti, A., Cesaroni, F. M. & Sentitu, A. (2018). Does gender matter in strategies adopted to face the economic crisis? A comparison between men and women entrepreneurs. In Mura, L. (Ed.) Entrepreneurship: Development Tendencies and Empirical Approach. London: IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.70292

Camisón, C., & Villar-López, A. (2014). Organizational innovation as an enabler of technological innovation capabilities and firm performance. Journal of Business Research, 67(1), 2891–2902.

Carboni, O. A., & Russu, P. (2018). Complementarity in product, process, and organizational innovation decisions: Evidence from European firms. R&D Management, 48(2), 210–222.

Carter, S., Shaw, E., Lam, W., & Wilson, F. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurship, and bank lending: The criteria and processes used by bank loan officers in assessing applications. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 427–444.

Chabaud, D., & Lebègue, T. (2013). Women leaders in SMEs: Looking back, looking ahead. RIMHE: Revue Interdisciplinaire Management, Homme Entreprise, 72(3), 43a–62a.

Chirwa, E. W. (2008). Effects of gender on the performance of micro and small enterprises in Malawi. Development Southern Africa, 25(3), 347–362.

Coleman, S. (2016). Gender, entrepreneurship, and firm performance: Recent research and considerations of context. In M. L. Connerley & J. Wu (Eds.), Handbook on Well-Being of Working Women (pp. 375–391). Springer.

Cowling, M., Marlow, S., & Liu, W. (2020). Gender and bank lending after the global financial crisis: Are women entrepreneurs safer bets? Small Business Economics, 55(4), 853–880.

Damanpour, F., Szabat, K. A., & Evan, W. M. (1989). The relationship between types of innovation and organizational performance. Journal of Management Studies, 26(6), 587–602.

Dohse, D., Goel, R. K., & Nelson, M. A. (2019). Female owners versus female managers: Who is better at introducing innovations? The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(2), 520–539.

Donate, M. J., & de Pablo, J. D. S. (2015). The role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management practices and innovation. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 360–370.

Doran, J. (2012). Are differing forms of innovation complements or substitutes? European Journal of Innovation Management, 15(3), 351–371.

Du Rietz, A., & Henrekson, M. (2000). Testing the female underperformance hypothesis. Small Business Economics, 14(1), 1–10.

Elam, A. B., Brush, C. G., Greene, P. G., Baumer, B., Dean, M., & Heavlow, R. (2019). Global entrepreneurship monitor: Women’s entrepreneurship 2018/2019 Report. Wellesley, M.A.

Entrialgo, M. (2002). The impact of the alignment of strategy and managerial characteristics on Spanish SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(3), 260–271.

Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. (2011). Institutions and female entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 37(4), 397–415.

European Commission. (2018). Annual Report on European SMEs 2017/2018. https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a435b6ed-e888-11e8-b690-01aa75ed71a1

Expósito, A., & Sanchis-Llopis, J. A. (2018). Innovation and business performance for Spanish SMEs: New evidence from a multi-dimensional approach. International Small Business Journal, 36(8), 911–931.

Expósito, A., & Sanchis-Llopis, J. A. (2020). The effects of innovation on the decisions of exporting and/or importing in SMEs: Empirical evidence in the case of Spain. Small Business Economics, 55(3), 813–829.

Expósito, A., Sanchis-Llopis, A., & Sanchis-Llopis, J. A. (2021). CEO gender and SMEs innovativeness: Evidence for Spanish businesses. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-021-00758-2

Edwards, T., Delbrigde, R., & Munday, M. (2005). Understanding innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: A process manifest. Technovation, 25(10), 1119–1127.

Faems, D., & Subramanian, A. M. (2013). R&D manpower and technological performance: The impact of demographic and task-related diversity. Research Policy, 42(9), 1624–1633.

Fairlie, R. W., & Robb, A. M. (2009). Gender differences in business performance: Evidence from the Characteristics of Business Owners survey. Small Business Economics, 33(4), 375–395.

Fernández, J. (2015). The impact of gender diversity in foreign subsidiaries’ innovation outputs. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 7(2), 148–167.

Foreman-Peck, J. (2013). Effectiveness and efficiency of SME innovation policy. Small Business Economics, 41(1), 55–70.

Foss, L., Woll, K., & Moilanen, M. (2013). Creativity and implementations of new ideas: Do organisational structure, work environment and gender matter? International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 298–322.

Freel, M. S., & Robson, P. J. (2004) Small firm innovation, growth and performance. Evidence from Scotland and Northern England. International Small Business Journal, 22(6), 561–575.

Freeman, C. (1974). The economics of industrial innovation. London, UK: Penguin Modern Economic Texts.

Goya, E., Vayá, E., & Suriñach, J. (2016). Innovation spillovers and firm performance: Micro evidence from Spain (2004–2009). Journal of Productivity Analysis, 45(1), 1–22.

Greco, M., Grimaldi, M., & Cricelli, L. (2015). Open innovation actions and innovation performance: A literature review of European empirical evidence. European Journal of Innovation Management, 18(2), 150–171.

Hall, B. (2011). Innovation and productivity. Nordic Economic Policy Review, 2, 167–204.

Hall, B., Lotti, F., & Mairesse, J. (2009). Innovation and productivity in SMEs: Empirical evidence for Italy. Small Business Economics, 33(1), 13–33.

Harrison, R. J., Jaumandreu, J., Mairesse, J., & Peters, B. (2014). Does innovation stimulate employment? A firm-level analysis using comparable micro data on four European countries. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 35, 29–43.

Hashi, I., & Stojčić, N. (2013). The impact of innovation activities on firm performance using a multi-stage model: Evidence from the Community Innovation Survey 4. Research Policy, 42(2), 353–366.

Hervas-Oliver, J. L., Sempere-Ripoll, F., & Boronat-Moll, C. (2014). Process innovation strategy in SMEs, organizational innovation and performance: A misleading debate? Small Business Economics, 43(4), 873–886.

Heyden, M. L., Sidhu, J. S., & Volberda, H. W. (2018). The conjoint influence of top and middle management characteristics on management innovation. Journal of Management, 44(4), 1505–1529.

Jaumandreu, J., & Mairesse, J. (2016). Disentangling the effects of process and product innovation on cost and demand. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 26(1–2), 150–167.

Johnsen, G. J., & McMahon, R. G. (2005). Owner-manager gender, financial performance and business growth amongst SMEs from Australia’s business longitudinal survey. International Small Business Journal, 23(2), 115–142.

Karlson, K. B., Holm, A., & Breen, R. (2011). Comparing regression coefficients between same-sample nested models using logit and probit. A New Method. Sociological Methodology, 42, 286–313.

Kelley, D. J., Brush, C. G., Greene, P. G., & Litovsky, Y. (2011). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2010 report: Women entrepreneurs worldwide. London: Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GERA).

Khalife, D., & Chalouhi, A. (2013). Gender and business performance. International Strategic Management Review, 1(1–2), 1–10.

Kiefer, K., Heileman, M., & Pett, T. L. (2022). Does gender still matter? An examination of small business performance. Small Business Economics, 58, 141–167.

Koellinger, P., Minniti, M., & Schade, C. (2013). Gender differences in entrepreneurial propensity. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 75(2), 213–234.

Kraus, S., Rigtering, C. J. P., Hughes, M., & Hosman, V. (2012). Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: A quantitative study from the Netherlands. Review of Managerial Science, 6(2), 161–182.

Laguía, A., García-Ael, C., Wach, D., & Moriano, J. A. (2019). “Think entrepreneur-think male”: A task and relationship scale to measure gender stereotypes in entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(3), 749–772.

Lee, I. H., Paik, Y., & Uygur, U. (2016). Does gender matter in the export performance of international new ventures? Mediation effects of firm-specific and country-specific advantages. Journal of International Management, 22(4), 365–379.

Lee, I. H., & Marvel, M. R. (2014). Revisiting the entrepreneur gender–performance relationship: A firm perspective. Small Business Economics, 42(4), 769–786.

Lemma, T. T., Gwatidzo, T., & Mlilo, M. (2022). Gender differences in business performance: Evidence from Kenya and South Africa. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00605-w

Lichtenthaler, U. (2016). Toward an innovation-based perspective on company performance. Management Decision, 54(1), 66–87.

Lin, C. Y., & Chen, M. Y. (2007). Does innovation lead to performance? An empirical study of SMEs in Taiwan. Management Research News, 30(2), 115–132.

Link, A. N. (Ed.). (2017). Gender and entrepreneurial activity. Edward Elgar Publishing.

López-Mielgo, N., Montes-Peón, J. M., & Vázquez-Ordás, C. J. (2009). Are quality and innovation management conflicting activities? Technovation, 29(8), 537–545.

Love, J. H., & Roper, S. (2015). SME innovation, exporting and growth: A review of existing evidence. International Small Business Journal, 33(1), 28–48.

Lyngsie, J., & Foss, N. J. (2017). The more, the merrier? Women in top-management teams and entrepreneurship in established firms. Strategic Management Journal, 38(3), 487–505.

Mahmutaj, L. R., & Krasniqi, B. (2020). Innovation types and sales growth in small firms: Evidence from Kosovo. The South East European Journal of Economics and Business, 15(1), 27–43.

Máñez, J. A., Rochina-Barrachina, M. E., Sanchis-Llopis, A., & Sanchis-Llopis, J. A. (2013). Do process innovations boost SMEs’ productivity growth? Empirical Economics, 44(3), 1373–1405.

Marlow, S., & McAdam, M. (2013). Gender and entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 19(1), 114–124.

Marlow, S. (2020). Gender and entrepreneurship: Past achievements and future possibilities. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 39–52.

Martínez-Rodríguez, I., Quintana-Rojo, C., Gento, P., & Callejas-Albinana, F. E. (2022). Public policy recommendations for promoting female entrepreneurship in Europe. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 18, 1235–1262.

Martínez-Roman, J., & Romero, I. (2017). Determinants of innovativeness in SMEs: Disentangling core innovation and technology adoption capabilities. Review of Managerial Science, 11(3), 543–569.

Marvel, M. R., Lee, I. H. I., & Wolfe, M. T. (2015). Entrepreneur gender and firm innovation activity: A multilevel perspective. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 62(4), 558–567.

Menzies, T. V., Diochon, M., & Gasse, Y. (2004). Examining venture-related myths concerning women entrepreneurs. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 9(2), 89.

Millán, J. M., Lyalkov, S., Burke, A., Millán, A., & Van Stel, A. (2021). ‘Digital divide’ among European entrepreneurs: Which types benefit most from ICT implementation? Journal of Business Research, 125, 533–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.034

Na, K., & Shin, K. (2019). Gender effect on a firm’s innovative activities in the emerging economies. Sustainability, 11(7), 1992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071992.

Nählinder, J., Tillmar, M., & Wigren-Kristoferson, C. (2012). Are female and male entrepreneurs equally innovative? Reducing the gender bias of operationalisations and industries studied, in Andersson, S., Berglund, K., Torslund, J.G., Gunnarsson, E. and Sundin, E. (Eds.), Promoting innovation-policies, practices and procedures, VINNOVA, Stockholm.

OECD. (2010). Measuring innovation: A new perspective. OECD Publications.

OECD. (2017). Policy brief on women’s entrepreneurship. European Union. https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/Policy-Brief-on-Women-s-Entrepreneurship.pdf

Orser, B. J., & Riding, A. (2018). The influence of gender on the adoption of technology among SMEs. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 33(4), 514–531.

Orser, B. J., Riding, A. L., & Manley, K. (2006). Women entrepreneurs and financial capital. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 643–665.

Oura, M., Zilber, S., & Lopes, E. (2016). Innovation capacity, international experience and export performance of SMEs in Brazil. International Business Review, 25(4), 921–932.

Pablo-Martí, F., García-Tabuenca, A., & Crespo-Espert, J. L. (2014). Do gender-related differences exist in Spanish entrepreneurial activities? International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 6(2), 200–214.

Pelger, I. (2012). Of firms and (wo) men: Explorative essays on the economics of firm, gender and welfare (Doctoral dissertation, München, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Diss., 2012).

Pettersson, K., & Lindberg, M. (2013). Paradoxical spaces of feminist resistance: Mapping the margin to the masculinist innovation discourse. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 323–341.

Prajogo, D. I., McDermott, C. M., & McDermott, M. A. (2013). Innovation orientations and their effects on business performance: Contrasting small- and medium-sized service firms. R&D Management, 43(5), 486–500.