Abstract

This article presents HUNCOURT, a complex open legal database for the quantitative analysis of the practice of the Hungarian Constitutional Court (HCC). Covering all HCC decisions and orders published between 1990 and 2021, the new database is published under an Open Database License and allows for advanced queries that go beyond the search engine options of industry-standard proprietary legal databases. We bypass the often inaccurate and time-consuming manual search options by providing a full text database that is entirely machine-readable, along with a full selection of available metadata. In the article, we also demonstrate the potential of the new database for scholarly research by presenting a use case for such analysis related to the self-reflexivity and reasoning of the constitutional court. We show that a state-of-the-art database opens up possibilities for applying quantitative text analysis and text mining to research questions that have so far been mostly analysed in a qualitative framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Replication data for our new open legal Hungarian Constitutional Court database available at the website of the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/6aek9/?view_only=2234b78383064401afe9dbe5ab4aee1e (Last Updated: 2023. 01. 27.).

During the centuries of constitutional scholarship focusing on legal text, qualitative methods served as the cornerstone for most studies. Since the 1990s, however, legal texts have increasingly been considered as data in the social sciences, just as many other textual sources from media articles to transcripts of legislative speeches. It has been steadily recognised that big data methods can be used in the fields of jurisprudence, law making and law enforcement (Devins et al., 2017), which have enabled researchers to understand phenomena that had not been studied before.

As the most important research questions facing legal scholars and innovative approaches no longer (or not only) stem from a legal-dogmatic approach, there is a tendency towards interdisciplinarity. In the last decades, the loosening of disciplinary boundaries and the increase in technical progress and computer power have enabled the spread of new empirical social science methods in the field of jurisprudence (Jakab & Sebők, 2020). The widespread use of complex computer analysis of large text corpora and statistical techniques started in the 2000s (Boumans & Trilling, 2016; Grimmer & Stewart, 2013).

The use of less traditional quantitative methods, such as text mining and network analysis, has emerged in Hungary in the field of social sciences (see Jakab et al., 2017; Jakab & Sebők, 2020; Pócza, 2018), in line with international trends (see Dyevre, 2020 for a discussion of the main techniques that can be potentially applied and used for the analysis of legal texts, Dyevre (2021) for a discussion of automated text analysis, Whalen (2016) for a discussion of network analysis and Coupette (2019) for the cross-referencing of judicial decisions) recognising that if we want to understand science, we should first look not at its theories or results, but rather at what those who practice it do.

The legal, computational and data science communities have recognised the potential of modern computer technologies such as machine learning, deep learning and natural language processing (NLP) to improve and advance all aspects of the existing legal system (Sharma & Sony, 2021). As a result, they have begun to collaborate to develop innovative computational and data-driven legal models that leverage these technologies (Sharma et al., 2021a, b). These models aim to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of legal research, case management and decision-making by automating the process of identifying relevant legal documents, providing more accurate and comprehensive search results and identifying patterns and trends in legal cases. Additionally, these models can also be used to predict legal outcomes (see Chi et al., 2022; Kowsrihawat et al., 2018; Lage-Freitas et al., 2022; Medvedeva et al., 2020, 2023; Sharma et al., 2022; Strickson & De La Iglesia, 2020), by analysing large sets of legal data.

Although there are some empirical studies available on the Hungarian Constitutional Court (HCC) decisions, which are essential milestones in the field of domestic constitutional case law research (see Jakab et al., 2017, in which the authors used a combination of qualitative and quantitative analyses to highlight the world’s leading independently reviewed cases, while it should be noted that they did not use text mining techniques to conduct their investigations, also worthy of note is Bodnár’s research (2021), who used various empirical methods—case law analysis and expert interviews—to find all cases where the HCC refers to foreign law, as well as Ződi’s analysis (2020), in which he used network research methods to analyse and investigate the interference of HCC decisions between 1990 and 2017), there is no comprehensive methodology and open database available yet, which overcomes the limitations of the HCC’s official website and provides the possibility of quantitative analysis of the HCC decisions. Therefore, the object of our research was the creation of a complex open legal database (named HUNCOURT after the court at the top of the legal hierarchy of the country) for the analysis of the practice of the HCC, which contains all HCC decisions and orders published between 1990 and 2021.

This article introduces HUNCOURT, which is published under an Open Database Licence and allows for advanced queries beyond the search engine options of industry-standard proprietary legal databases. It also presents the main results of our first research project using HUNCOURT. We bypass the often inaccurate and time-consuming manual search options by providing a full-text database that is entirely machine-readable and a full selection of available metadata. The data was collected to develop a high-quality infrastructure so that HUNCOURT could be used to solve real-world problems and to be accessible, reproducible, reliable, sustainable, updatable and robust as a new open legal database for future research using the corpus. Our database has enabled the subsequent implementation of NLP and the application of machine learning techniques. We intend to provide HUNCOURT as a valuable resource for further quantitative research exploring the case law of the HCC using different approaches. Thus, we seek to contribute to the ongoing discourse of emerging legal informatics.

We also conducted pilot research to test our database. Our first research using HUNCOURT, considering the emerging trends in quantitative text analysis in Hungary (Boda & Sebők, 2018; Bolonyai & Sebők, 2020; Nyitrai, 2021; Sebők et al., 2021; Tikk Domonkos, 2007), so we also demonstrate the potential of the new database for scholarly research by putting forth methodological notes and preliminary results related to a substantive research agenda related to the constitutional reasoning of the HCC. We show that a state-of-the-art database opens possibilities for applying quantitative text analysis and text mining to research questions that have been only analysed in a qualitative framework so far.

Since design research is crucial in a field focused on designing successful artifacts, in this article, we present our findings in line with the Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM) as this methodology aims to develop and evaluate innovative solutions to complex problems in the field of information systems (Gregor & Hevner, 2013; Hevner et al., 2004; Peffers et al., 2007). First, we identify and illustrate the existing problem of HCC case law research, and then explain our motivation for creating our database, which stemmed from the identification of the problem, and we discuss how the design and development of HUNCOURT can address the identified problem. We proceed to present a review of the relevant literature and define the solution’s objectives. Next, we describe the approach to creating the corpus and the tools and steps used to build the infrastructure. The content and structure of the database are then outlined in the context of the artifact description. We then provide evidence that the artifact is useful through an evaluation, so in the remainder of the paper, we briefly outline the main results of our first text mining research project using the database focusing on the self-reflexivity of the HCC. Finally, we draw conclusions and consider further use cases and the availability of HUNCOURT.

I. Problem Identification and Motivation: the Need for a New Standard Database

In recent years, different focuses and approaches have been used to examine qualitatively and quantitatively the practice of the Constitutional Court in Hungary and elsewhere (see, for example Bodnár, 2021; Gárdos-Orosz & Szente, 2021; Jakab et al., 2017; Jakab & Fröhlich, 2017; Kelemen, 2013; Komárek, 2017; Szente, 2013; Ződi, 2020). Although plenty of articles in the literature analyse the practice of the HCC qualitatively, the scope of empirical studies is much narrower. Only a few examples show methodological possibilities and practical implementation for the text-based processing of the HCC decisions. Hence, there is currently limited (or hardly any) literature comprehensively examining the HCC case law along particular indicators. These are mainly due to the limitations of the presently available domestic legal databases and the official website of the HCC.

The operation of the three branches of power in modern democracies generates enormous amounts of data. As a result, many legal documents are now available on the internet to promote transparency. Still, there is a limitation because such information is usually published in an unstructured format. In the study of the law, the legal system and the various legal institutions, infrastructure in the form of databases and multiple tools are often needed to identify meaningful patterns and promote new insights. Infrastructure building is one of the biggest challenges (Weinshall & Epstein, 2020). Although the available industry-standard databases represent a significant improvement, their structure makes them less suitable for answering complex research questions or a complete case law analysis rather than intended to assist practitioners.

Recently, the development of digitalisation and computer technology has led to a trend of creating various digitalisation projects. Of course, many industry-standard legal databases are already available worldwide, including in Hungary. However, it is crucial to consider accessibility in a nuanced way, as this does not only mean that legal documents, such as decisions of constitutional courts, should be publicly accessible but also that they should be published according to the same criteria, in a similar format, with as many tools and metadata as possible to facilitate their searchability and discoverability (van Opijnen et al., 2017). In addition, each constitutional court’s official website would also be used for big data research on constitutional court practice. However, we have also found that the filtering that can be conducted with these is always limited: it is either under- or over-filtered, it is challenging to provide accurate results and it only offers manual search options, which are often not only inaccurate but also time-consuming.

There are currently three sources for HCC case law. One is the official website of the HCC, where all HCC decisions are published. The other two (Jogtár and Jogkódex) are industry-standard legal databases which obtain their data from the HCC’s official website. Indeed, we could not be independent of these sources when we created HUNCOURT. On the one hand, we cannot be completely independent of the source of the HCC decisions, which is the official website of the HCC, because the HCC is legally obliged to publish its decisions in digital format on its website.Footnote 2 That is why each legal database obtains the text of HCC decisions from there. On the other hand, since HCC decisions (and other legal documents) are published in a slightly more structured way in the industry-standard legal databases used by practitioners, we have used these databases to access the full text of decisions.

A comparison of the characteristics of these databases and HUNCOURT is presented in Table 1, which points to how the database we have created can go beyond those limitations. Our result and added value are thus that we have created an open legal database that can map the entire HCC case law due to its metadata structure and answer many research questions that are not feasible using industry-standard databases and the HCC website.

While we do not dispute the need for theoretical research and qualitative analysis, this paper argues that a quantitative approach is necessary. It is the most comprehensive way to examine the full text of thousands of HCC decisions. Justification for this approach can be seen in Table 1, where we have highlighted the characteristics of the usability of the available databases and their limitations that constrain a comprehensive study covering the entire HCC practice. Based on the above, the innovation of HUNCOURT lies in the fact that it goes far beyond the queries that can be made using various industry-standard legal datasets and the Constitutional Court’s website’s search engine to obtain relevant legal material via the internet. Thus, the corpus created can answer new research questions concerning the practice of the Hungarian Constitutional Court and empirical support for issues previously raised in the literature. However, so far only been examined by qualitative means, typically case studies.

Although text mining, which allows the software to extract information from text documents, is not a new technology per se, its application in the field of jurisprudence has come to the fore with the advent of big data and the need to understand legal documents, which are now available in large quantities. Text mining is thus able to replace processes that are still often manual, such as keyword searches using internet search engines. As indicated earlier, the official websites of each constitutional court would also be used for big data research on the practice of constitutional courts.

Accordingly, the quantitative studies conducted so far on domestic Constitutional Court case law have been predominantly limited to research using the search engine on the official website of the Constitutional Court, i.e. researchers have relied on manual analysis (see Bodnár, 2021). However, we have found that filtering with the website search engine is always limited: it is either under- or over-filtered, it is challenging to provide accurate results and it only offers manual search options, which are often not only inaccurate but also time-consuming. Therefore, this technique is unsuitable for a comprehensive search that meets legal research requirements. The search results usually contain too many false hits and “noise” for irrelevant documents and thus cannot be used to automate legal research. Nevertheless, if we look at the HCC’s website, for most of the filtering criteria, it is only possible to perform a detailed search for cases initiated after, i.e. after 1 January 2012, when the Fundamental Law entered into force. However, ignoring these biases can significantly affect the validity of search results based on existing databases.

In contrast, even in an interdisciplinary field, the application of text mining (once the raw material, i.e. the text needed to create the corpus, has been identified and obtained) is easy and relatively simple. To illustrate the limitations of the HCC’s official website, a simple example has been provided to compare the use of the Constitutional Court’s search engine with the possibilities text mining offers. The results are summarised in Table 2.

As can be seen from the results in the table above, a search using the filter on the HCC’s official website and a search using the text mining methodology show strikingly different results in many cases. For some of the terms searched for in the context of the Constitutional Court’s practice, the website filter cannot handle and filter the results in one single search. Additional criteria, such as a year-by-year breakdown, must be specified for delisting decisions. Such constraints do not appear to arise in text mining.

It can also be noted that while HCC’s search engine only lists the relevant results, it cannot count the number of terms searched for. By contrast, as indicated in the columns summarising the search results using HUNCOURT, text mining can also be used to measure the occurrence of action terms in the text of individual legal documents.

We also obtained different results when we searched the HCC website’s free text search engine for each term without or between quotation marks. In general, only in the latter case did the search engine return results that corresponded to the search term since, without quotation marks, the search engine searches for both elements of the term separately. This was most strikingly the case for the term historical constitution. Table 2 shows that the text mining resulted in 99 HCC decisions containing the word “historical constitution” for 1990–2021. In contrast, the search for “historical constitution” on the HCC website only returned 28, i.e. the search engine did not find all the decisions in which the HCC referred to the historical constitution. However, without quotation marks, the search interface of the website lists 224 decisions. Most of these do not contain the term “historical constitution” but only fragmentary hits such as “historical facts”, “historical value”, “historical precedents”, “historical perspective”, “historical evocation”, “historical situation”, etc. This means that if we want to retrieve the 99 HCC decisions referring to the historical constitution via the website, we have to open the 224 decisions listed by the website’s search engine one by one and manually filter the relevant hits.

The purpose of our first research, applied to the developed database, is also based on a problem statement that aims to overcome a gap in the literature. Several studies on the HCC have been published in recent years that focus on the specific problems of constitutional reasoning (by constitutional interpretation or reason, we understood as the justification given by constitutional judges for their decisions) in an illiberal democracy (Drinóczi & Bień-Kacała, 2019; Halmai, 2019; Tóth, 2019). Legal scholars have extensively studied the nature and attributes of constitutional decision-making since the democratic transition period of 1989–1990 in Hungary. They have examined different methods of interpretation, some relying solely on the constitutional text and others using external sources to understand the purpose and content of constitutional provisions (Pokol, 2002; Zifcak, 1996). In the 1990s, the HCC emphasised dogmatic reasoning and analysis and established standards for constitutional interpretation through a self-reflexive approach (Jakab & Kazai, 2021; Kovács & Tóth, 2011). Self-reflexivity, as we understand it from the literature, is the process by which a constitutional court reflects on its own interpretive methods and decisions, particularly when interpreting the text of the constitution (Sebők et al., 2023).Footnote 3

The adoption of the new Fundamental Law by the parliament in 2011, initiated by the Orbán-government, sparked further debates on constitutional interpretation in domestic literature. The HCC’s varying levels and focal points of methodological self-reflection provide a rich area for analysis of interpretive practices over a more extended period (Aaken & List, 2017; Sólyom, 2015). Nevertheless, a comprehensive study of the interpretative methods used by the HCC and research mapping the reasoning of judges has not yet been carried out; however, research questions have arisen (primarily, but not exclusively) concerning the self-reflexivity of constitutional argumentation (Sebők et al., 2023), which are yet unanswered or not yet empirically supported. In our first research using HUNCOURT, we intend to answer these emerging questions by conducting empirical research.

Literature Reviews

Digital transformation is an organisation-wide endeavour involving various technical and cultural changes (Shaughnessy, 2018), such as using digital technologies—social media, mobile, analytics and embedded devices—to maximise customer experience and enable the design and adoption of new business models (Horlacher et al., 2016). It involves moving away from traditional forms of communication and embracing innovative ways of interacting with customers and partners (Altameem et al., 2006; Hess et al., 2016; Jonathan, 2020; Matt et al., 2015).

Information technology service management (ITSM) is a combination of IT services and various IT technologies that ensures an organisation’s successful implementation of IT. A correctly implemented ITSM delivery system raises the calibre of IT services, ultimately boosting the organisation’s capacity and output (Sarwar et al., 2023). It is essential for providing public services, as digital transformation in the public sector is an important endeavour instrumental in public administration effectiveness and promoting democratic values.

In contrast to previous waves of digitalisation, which focused on transitioning from traditional analogue to several digital services to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of government services, digital transformation aims to redesign and reengineer government services from the ground up to meet changing user needs (Mergel et al., 2018). However, several factors need to be identified and configured to realise the benefits of digital transformation, so although e-government improves the convenience and accessibility of public services and information for citizens, its success depends on citizens’ willingness. The literature provides a long list of models and frameworks to identify antecedents and evaluate the success of digital transformation (see, e.g. Homburg, 2008; Jonathan, 2020). Public organisations must negotiate and approve digitalisation projects, and lack of funding is one of the primary causes of e-government initiatives failing (Gil-García & Pardo, 2005). Other factors such as IT infrastructure, skilled labour, dynamism and openness of the economy, and environmental factors also influence how public organisations manage digital transformation (Altameem et al., 2006).

Leaders must ensure that digital technologies are appropriately harnessed and aligned with the organisation’s objectives and develop the proper organisational structure and culture to align technical and social systems (Horlacher et al., 2016). Digital transformation can improve organisational performance and make it easier for stakeholders to participate in public sector decision-making. Still, it requires organisational structures, business processes and human resources changes. These changes can have implications for aligning technologies with new digital technologies and for organisational factors (Jonathan, 2020).

Several disciplines, including organisational science and public administration, discuss the meaning and significance of reflexivity (see, e.g. Cunliffe & Jun, 2005; Farmer, 1995; Harmon, 1995; Quinn, 2013). Self-reflexivity is a critical concept in organisational science that refers to the ability of individuals or organisations to reflect on and learn from their own actions, experiences and processes. It involves critically examining one’s assumptions, biases and behaviours and an ongoing process of self-awareness and self-improvement. Self-reflexivity has been studied extensively in organisational science; Argyris (1976, 1977) work on double-loop learning and Schön’s research on reflection-in-action (Schön, 1983) are particularly relevant to organisational self-reflexivity. They argue that individuals and organisations should engage in ongoing reflection and critical inquiry to uncover underlying assumptions and values that may hinder their effectiveness. This type of self-reflexivity can lead to deeper learning and improved performance. Weick’s concept of sensemaking (1995) is also relevant to self-reflexivity, as he argues that individuals and organisations engage in ongoing sensemaking processes in which they construct and revise their understanding of their environment and their role within it. This type of self-reflexivity can help organisations to adapt to changing circumstances and improve their decision-making.

Exposing inconsistencies in organisational policies and practices requires adopting a critically reflexive stance and considering various and multiple interpretations of texts, organisational documents and practices (Cunliffe & Jun, 2005, p. 238). Organisational documents can serve as a valuable tool for self-reflection in organisations. By reviewing and analysing documents such as strategic plans, annual reports and performance metrics, organisations can gain insights into their performance and identify areas for improvement. Reflective practice can be positively associated with individual and organisational learning, an important innovation driver.

In line with the digitalisation objectives of the European Union (see 2030 Digital Compass: the European way for the Digital Decade)Footnote 4 and its policy programme, which provides guidelines for the definition of priority development areas for digitalisation until 2030, Hungary has adopted a National Digitalisation Strategy for the period 2022–2030, which is based on the following four pillars: digital infrastructure, digital competence, digital economy, digital state.Footnote 5 In addition to the digitalisation of e-government services and public administration, this strategy also includes the digitalisation of the justice system aligned with the strategic priorities set by the European Union (see Communication from the Commission on the Digitalisation of justice in the European Union).Footnote 6

The electronisation of specific steps in the judicial process is an integral part of the quality of justice systems. The electronic initiation of proceedings and the online monitoring of their progress facilitate access to justice and reduce delays and costs. Negatively, these digitalisation improvements do not cover the organisation of the Constitutional Court, as it is separate from the ordinary judicial system. Although the Supreme Court of Hungary (Curia) has a medium-term strategy that includes IT developments, the Constitutional Court does not have such a document. As reflected in Act XC of 2021 on the Central Budget of Hungary for the Year 2022,Footnote 7 the Constitutional Court launched an ambitious project at the beginning of 2021. The aim was to establish an electronic database of European Constitutional Court decisions in English. This would assist practitioners in constitutional reasoning and strengthen the reasoning techniques of the constitutional judges and their staff in the European constitutional courts.

The database could facilitate a comparative analysis of European constitutional courts’ practice for practitioners and academics.Footnote 8 Despite its original objectives, according to the budget law for the following year (Act XXV of 2022 on the Central Budget of Hungary for the Year 2023),Footnote 9 the database should have been functioning as of mid-2022; the database was still not openly accessible. It is also important to note that this proposed development does not cover our data of interest: Hungarian court decisions. This creates a gap in database availability and a need to create new infrastructure that supports such research.

Focusing on the purpose for which HUNCOURT was created, we briefly review quantitative research on HCC case law. Many of the questions facing legal scholars and practitioners can only be answered by analysing and studying extensive collections of legal documents—legislation, treaties, court decisions and jurisprudence. Lawyers deal with words, and law is a complex network of interrelated texts. The search for analysis, commentary, interconnection and interpretation of the various legal documents has occupied legal scholars for centuries. The study of legal texts is as old as jurisprudence itself. Still, the research needs to be more extensive in many ways. The analysis of legal texts (before the technical progress of recent decades) has long been dominated by qualitative methods. What is new is the emergence of a whole range of quantitative empirical research methods, including, for example text mining techniques, to help researchers navigate and analyse the ever-growing sea of legal and legally relevant documents. Nevertheless, despite this apparent trend, researchers still rely primarily on qualitative studies to analyse constitutional court practice, even though quantitative (or hybrid research-based) approaches can also answer new research questions. Here we highlight only the research that goes methodologically beyond the purely theoretical-dogmatic and case study-based qualitative analyses.

The CONREASON project (Jakab et al., 2015) seeks to develop the most comprehensive and systematic analysis of constitutional reasoning to date. The project aims to enhance the use of rigorous social science methods in legal studies and to enlighten normative debates on constitutional reasoning. The project focuses firmly on the language of constitutional law rather than the law itself. As the constitutional review has become more prevalent, courts have been called upon to decide increasingly essential policy questions. This poses a challenge for non-elected judges, as the legitimacy of their decisions and a constitutional review depends on the reasons that underpin them. The project aims to systematically study the reasoning practice of constitutional courts, comparing differences and similarities. The research questions include identifying similarities in dominant systems of interpretation, patterns of argumentation, critical concepts used to structure argumentation, the extent to which constitutional argumentation is rhetorical or analytical, and whether there are similarities in practice between constitutional argumentation in different countries. The research is based on a selection of the 40 leading judgments from 19 countries (760 decisions altogether). The focus primarily compares legal systems rather than examining the entire Hungarian Constitutional Court case law.

Comparative Constitutional Reasoning (Jakab et al., 2017) explores how the language of judicial opinions is responsive to the political and social context in which constitutional courts operate. It examines the practices of constitutional judges across a range of legal systems, including the European Court of Human Rights and the European Court of Justice. It employs qualitative and quantitative analysis to provide a comprehensive and systematic account of constitutional reasoning to date. The authors argue that courts are reason-giving institutions and that argumentation plays a central role in constitutional adjudication. However, a cursory look at different constitutional systems suggests significant differences in the practices of constitutional judges, whether in matters of form, style or language. The volume aims to identify universally common aspects of constitutional reasoning and examine whether common law countries differ from civil law countries. It also focuses on leading cases independently scrutinised by 18 legal systems worldwide, providing a comprehensive and systematic examination of constitutional reasoning. The authors also examine whether common law countries differ from civil law countries in the practice of constitutional reasoning.

In their research, Ződi and Lőrincz (2020) set out to examine how often the practice of the HCC has been cited in the practice of the courts by year since 2010. The quantitative part of the research aimed to examine the judgments in the corpus of court decisions and measure the extent to which these decisions refer to the Fundamental Law and the decisions of the Hungarian Constitutional Court. From these references, conclusions were drawn as to how often, in what types of cases, and at what levels of court these two types of sources of law are cited by the courts. However, they also draw attention in the study to the limitations of the searches that the HCC’s website allows. Further research requires access to data that cannot be found as intended in the otherwise very systematically developed open-access search system of the HCC. They urge that the database of the HCC should be searchable by other means than simple text search (Ződi & Lőrincz, 2020).

In another study, Ződi (2020) analysed the network of inter-references between the decisions of the Hungarian Constitutional Court. The research concludes that analysing the reference network of the Constitutional Court’s decisions between 1990 and 2017 did not give rise to any significant surprises. The network that emerges is very similar to the network of decisions of other courts (such as the US Supreme Court). The research concludes that an entirely new phase in the life of the HCC started in 2012 (with the entry into force of the Fundamental Law), which has redrawn both the overall decision network and the structure of the smaller subsets of decisions examined. Finally, the research demonstrates that network research can be an exciting complement to doctrinal jurisprudence. Even if a non-qualitative methodology was used in the other studies currently available, the research is still limited: mostly manual searches were carried out by researchers using the public online database available on the HCC’s website. As we have illustrated (see Table 2) and as Ződi and Lőrincz’s research (2020) sheds light on, analysis using a website’s search engine is in many ways unsuitable for more profound text mining research.

All of the above, it is clear that there is currently no online database on the case law of the Constitutional Court that can adequately support academic research. For this reason, our database aims to fill this gap, but first of all, we would like to emphasise that our database effectively facilitates and complements the searchability and accessibility of decisions and orders published on the official website of the HCC to answer research questions on the practice of the HCC but does not seek to replace or compete with other available sources of constitutional case law. Our primary motivation was to create a database that could contribute to academic research. Therefore, we do not intend to replace the official HCC website nor to replace currently available industry-standard databases (which actively contribute to the acquaintance of legal system documents from other perspectives and assist the work of practising lawyers, judges and solicitors). However, as we pointed out in the problem statement, the available databases have shortcomings which make them unsuitable for processing legal texts as large amounts of data. Nevertheless, the first research using HUNCOURT (and follow-up research using the database) can provide beneficial results that could be useful for the HCC as well.

Defining Objectives for a Solution

To fill the identified gap in the literature, we seek to go beyond the previous literature and research. As a novelty, we have created a complex corpus of raw data, including HCC decisions and orders published between 1990 and 2021. This is unique in that no one has ever produced and analysed such a structured corpus of data on HCC decisions.

Overall, just because HCC decisions are openly available, the texts of decisions are no longer stored in an image or scanned pdf format. The text (at least for domestic Constitutional Court decisions) no longer needs to be converted (into machine-encoded text formats using optical character recognition (OCR)) for full use in research (Tonkin & Tourte, 2016) and does not mean that the database is easily accessible. As can be seen through the examples summarised in Table 2, keyword searches using the HCC website could be more user-friendly and only allow complex text searches. Also, the results could be more accurate and contain inferior search features.

As summarised in Table 1, the currently available databases need to be revised to answer our research questions, such as the self-reflexivity of HCC. They cannot be used for full-text analysis due to their limitations. Since text mining research can go beyond the boundaries of industry-standard databases (cannot list all decisions, over-filter or fail to find all decisions, and does not provide an export function for the search list for further processing, each document has to be opened one by one), it is a suitable method and solution to answer our research questions. Due to its design and the metadata available, it is also ideal for future longitudinal research and offers the possibility for NLP research and machine processing.

In short, there was a need for a database to address these shortcomings and limitations and allow for efficient searching, analysis of text as data and exploration of different content features and patterns. Gregor and Hevner (2013, pp. 341–342)—who build on Purao’s (2002) research—distinguish three levels of different Design Science Research (DSR) “outputs”, i.e. types of DSR contributions. They claim that an individual DSR project may result in artifacts at one or more of these levels, ranging from specific instantiations at level 1 (situated implementation of artifact) in the form of products, instantiations and implemented processes to more general type of contributions at level 2 (nascent design theory—knowledge as operational principles or architecture) in the form of developing design theory such as constructs, design principles, models, methods and technological rules, to well-developed (mid-range and grand theories) design theories at Level 3 (well-developed design theory about embedded phenomena).

We position the development of HUNCOURT as a DSR project within level 1 and level 2 contribution type since it is an implementation of a specific artifact (namely the new database itself—level 1) and a developed research method based on HUNCOURT (pilot research on HCC’s self-reflexivity—level 2). In the next chapter, we describe the main features of HUNCOURT, and we present the main results of our first research to demonstrate that the database can provide a starting point for a comprehensive mapping of the practice of the HCC.

HUNCOURT: Database Structure and Variables

As mentioned above, the data was collected to develop a high-quality infrastructure so that the database could be used to solve real problems. HUNCOURT is comprehensive and complex to achieve this, including all HCC decisions and orders published between 1990 and 2021. The database thus contains 5336 decisions and 5427 orders. In addition to the corpus of decisions, HUNCOURT also contains various metadata related to each decision.

We obtained our data on HCC decisions through the Jogtár databaseFootnote 10 and then cross-checked our data against the HCC’s website, where officially published decisions are openly available. All 15 metadata variablesFootnote 11 have been automatically extracted from the text of HCC decisions (except for download links, which were automatically extracted from the data source). Except for manual translation of Hungarian language data entries for certain tables, no qualitative work was necessary for the creation of HUNCOURT proper.

We are aware that the orders are not substantial decisions. Still, since the Constitutional Court is obliged to give reasons for its orders, as it is for its decisions, they may also contain valuable findings that may be important in answering various research questions that we have seen no reason not to include in HUNCOURT. Also, it contains both concurring and dissenting opinions. Although concurring reasoning and dissenting opinions are not part of the substantive decision, they are still necessary to confirm (or possibly refute) the hypotheses formulated for our further research and are therefore included in the database. However, a later step could be to separate them from the substantive decision and make them separately investigable.

We first collected the list of internal filenames through an API upon searching for all the legal documents issued by the HCC. The API response also included essential metadata, such as the number_of_decision and the title. From the list of filenames, we then generated the links pointing to the source of the document. Then, through an automated web browser, we iterated through every link and downloaded the html source code from which we generated all other variables and retrieved the texts of the documents.

We have also tried to ensure consistency in HUNCOURT so that all HCC decisions and orders have been treated similarly. As each text had a different character encoding, to map all known characters to a single scheme, we ensured that all texts were converted to UTF-8. Data pre-processing is the starting point of any data analysis. To compile the texts and metadata of the legal documents under study, we pre-processed the corpus after obtaining the texts (Welbers et al., 2017). A text is essentially nothing more than a set of words or characters. However, when we usually engage in linguistic modelling or natural language processing, we tend to focus on the terms rather than only on the character-level depth of our text data (Garten et al., 2019). One reason for this is that in linguistic models, individual characters do not have much “context”. Characters such as “d”, “a”, “t” and “a” do not carry meaning individually, but once they are arranged into words, they can create the term “data”. This text data can be accessed and systematically examined using text mining, which structures and aggregates the data largely automatedly.

To improve the computational performance and accuracy of the text analysis method, the following three necessary pre-processing steps are usually performed: tokenisation (Benoit & Matsuo, 2022; Mullen et al., 2018), normalisation: lowercasing and stemming (Porter, 2001), removing stopwords (Welbers et al., 2017). However, in our current procedure, we did not perform tokenisation, stemming, lemmatisation and other bow preparation. Still, we examined the occurrence after extracting the complex word forms from the text as a string. This is because Hungarian is a conjugated language, so the words in the dictionary were searched with conjugations, and after tokenisation, we would have lost hits. In our research, we looked at the frequency of occurrences of the full matching strings in our dictionary. In the pre-processing, all non-alphabetic characters (punctuation, digits, Roman numerals, etc.) were removed, and the text of the resolutions was written in lowercase. In addition, duplicate texts in the source data had to be filtered out. Duplications are due to the input data frame’s structure, not errors.

For our analysis, we used two variables from the available metadata: the year of publication of the decision and order and the list of citations of external legal documents. The year variable is an integer; the variables containing the cleaned texts and citations are strings. Table 3 presents the first five rows of our input tableFootnote 12.

Our complete database contains more metadata than the inputs listed in Table 2, which can also be used for future research. The automatically collected variables and their brief explanations are listed in Table 4.

A Use Case for Applying HUNCOURT in a Research Setting: The Self-reflexivity of the HCC

In order to reach the usability of the newly created solution, we initiated an internal research project that served as the first step in evaluating HUNCOURT. This pilot study confirmed that the solution is fully applicable for the intended purposes of conducting quantitative and qualitative research on the Hungarian Constitutional Court. In so far as communication is concerned, the full database is already made available via a publicly available repository. And the subsequent research articles will serve the purpose of getting the word out about this infrastructure’s availability. The use case, dedicated to the testing of HUNCOURT, was focused on the self-reflexivity of the Hungarian Constitutional Court.

Among the approaches to text analysis, we built on the so-called counting and dictionary methods approach (Boumans & Trilling, 2016) to carry out the first research using HUNCOURT. We used text mining research to determine how regularly the Hungarian Constitutional Court reflects on the interpretative methods used in its own reasoning.

The first hypothesis of our research posits that a minimum of 51% of all HCC decisions contain an explicit reference to at least one method of interpretation. We suggest that self-reflection by individual judges and the court as a whole can be identified through language indicators in the reasoning of the decisions. Although self-reflection and its linguistic manifestation are not necessary conditions for a legitimate decision, it is often present in legal reasoning to reveal the thought process of the judge(s). Our research aims to investigate the extent to which these methods of reasoning are present in the HCC’s jurisprudence, as well as the frequency and variability of each method. The hypothesis is based on existing literature and the understanding that Hungarian legal culture strongly emphasises proper judicial reasoning in jurisprudence (Sebők et al., 2023).

The second hypothesis suggests that the sample of the 100 doctrinally most important decisions have more explicit references to at least one method of interpretation per decision compared to the full sample of decisions. The second hypothesis is based on the assumption that the Court goes out of its way to ensure this convention is upheld for what the legal community considers landmark decisions (Sebők et al., 2023).

Our method for analysing the specific interpretative methods of constitutional reasoning involved the selection of relevant keywords based on previous academic research. Then, we applied text mining to determine the frequency of these keywords in the corpus of the HCC decisions. Our approach involved counting and clustering the occurrences of keywords in each document according to categories of the methods of interpretation. We also performed statistical analysis and normalised the data by the length of decisions. The resulting measure is referred to in our analysis as the Count Index.

To identify search terms for our analysis, we used a multi-level approach. We first selected words based on relevant literature to ensure that the keywords highlighted in previous research on the practice of the Constitutional Court were included in our dictionary. We have selected keywords that, according to mainstream jurisprudence, are used in constitutional law to describe one or another method of interpretation (i.e. the choice of keywords/terms for this dictionary was not arbitrary, we are looking for the exact words that other people have searched for in further qualitative research in the literature). And once the dictionary was compiled, we launched a text mining search of HUNCOURT for these keywords, i.e. linguistic signs of using each scientifically identified method of interpretation.

Additionally, we closely examined 100 doctrinally most important (“top 100”) decisions selected by experts (see Gárdos-Orosz & Zakariás, 2021) and identified words used to describe methods of interpretation. Table 4 presents the six categories of the methods of interpretation and the corresponding keywords. We also carefully re-examined the “top 100” decisions referenced in our study, collecting the terms used to refer to the interpretative methods used within them. Our research design counted various versions of keywords associated with different reasoning methods, which we derived from the literature. We also extensively validated the matches to ensure that only relevant matches were counted.

The keywords (the most obvious ones related to specific methods of interpretation) were selected based on academic research on constitutional interpretation and constitutional reasoning. The classification is summarised in Appendix (Table 6). It is important to note that some terms had to be excluded from the search list. These words are not associated in meaning with any of the methods of interpretation, which is why we had to exclude them from the filter. The list of stop words (and stop phrases) was compiled in two iterations. The preliminary list of stop words, drawn from legal doctrine and theory on the interpretation of the law by the Constitutional Court and from the literature, was applied to a token-based text cleaning procedure in the following order.

We first exclude any token that is a conjugate of any stop word or stop phrase in our text. When we considered a stop phrase, we marked all tokens as matching, evaluating their conjugate forms. We then applied our dictionary-based keyword counting to stopwords and tokens using the same approach. We then searched for occurrences of keywords or key phrases exceeding the threshold in any document; in other words, for each record, we checked whether it contained six or more matching keywords or key phrases.

We collect all outliers to identify outliers and expand the list of stop words and phrases. Outliers are observations where the occurrence of any keyword exceeds 5. We then manually place the terms that are false positives of keyword matching. Thus, the phrases initially blacklisted are historical facts, scientific truths, justice, a serving of justice, truth content and Office of History. This list has been extended to include the following phrases (with examples of problematic occurrences in the text, all filtered using the accompanying stopword list): truths (scientific truths); justice (to justice minister; judicial; for justice); justice servant (to justice; in justice; for justice; justice provider; justice); justice keep (to truthfulness); historical office (to historical office).

The translation of the blacklist of phrases:

-

“történeti tényállás” ~ historic facts – we want references to historical reasoning, not references to historical facts;

-

“tudományos igazság” ~ scientific truths – we want references to metajuristic reasoning, not references to scientific facts;

-

“igazságügy” ~ justice – the root of words including institutions or members of justice service;

-

“igazságszolg” ~ serving of justice – stemmed root of words including institutions or members of justice service;

-

“igazságok” ~ truths – appears only as part of the phrase scientific truths;

-

“igazságtart” ~ truth content – appears only as part of references to facts;

-

“történeti hivatal” ~ Office of History.

We then manually extended the list of stopwords and stop phrases with the newly identified problematic terms. These were identified during manual inspection and verification and during a qualitative case study to complement our quantitative measurement. To illustrate using a practical example, the word “grammatical interpretation” was used as a contraction of “grammatical sense” in the HCC decisions on referendums. In these cases, the grammatical sense did not refer to the method of interpretation itself but, for example, to the clarity of the wording of the question to be put to the referendum, the requirements of “grammatical sense” (for this, see, among other things, 51/2001 (XI. 29.) Constitutional Court decision).

Finally, we checked their word environment with a window of 4 words (in both directions), validating the results and then recalculating the occurrences of the keyword phrases searched for in the texts, making sure that only those results that indicate the use of methods of interpreting the text of the HCC decisions were extracted.

The text mining results, i.e. the description of the corpus by category, are presented in Table 5. There is a significant difference between the two groups in the proportion of documents containing at least one keyword.

There is a notable difference in the proportion of documents with at least one keyword of any category between the two groups: 99% of the expert-selected, most essential decisions contained keywords. In contrast, this proportion is only 44% for the entire corpus of HCC jurisprudence between 1990 and 2021.

Our results, using the methodology described, show that the “decision based on former decisions” methodology is the most prevalent in the entire corpus, appearing in 30% of documents containing related keywords, followed by references to “contextual” argumentation (21%). Among the top 100 decisions, references to “contextual” methodology are the most frequent (75%), followed by “decisions based on former decisions” (64%), then “teleological” (48%) and “historic” (48%). Across all categories, the proportion of documents with at least one keyword is significantly higher among the top 100 than in the entire corpus.

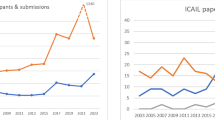

Figure 1 compares the distribution of the percentage of documents that include keywords in a specific year. Most of the top 100 HCC decisions have at least one self-reflective keyword in most years, except for 2007. However, the same percentage is mostly below 50% among the remaining HCC decisions, though it has increased since 1990 and went above 50% in 2015. Our analysis of explicit references to types of constitutional reasoning supports our hypotheses. It is worth noting that the averages reveal significant temporal variations in different periods.

Source: Sebők et al. (2023)

The proportion of reasonings with keywords in a given year.

Conclusion

This paper presented a complex new open legal database, named HUNCOURT, for the quantitative analysis of the practice of the Hungarian Constitutional Court over more than two decades. The new database is published under an Open Database Licence, covering all HCC decisions and orders published between 1990 and 2021. It allows for advanced queries that go beyond the search engine options of industry-standard proprietary legal databases.

As we pointed out in this article, a large number of legal documents are now available on the internet. Still, there is a limitation because such information is usually published in an unstructured format. Also, we found that filtering with the website search engine is always limited: it is either under or over-filtered, it is challenging to provide accurate results and it only offers manual search options, which are often inaccurate and time-consuming. Therefore, this technique is unsuitable for a comprehensive search that meets legal research requirements. Thus, with our complex open legal database, we bypassed these limitations by providing a machine-readable text database, along with the full selection of available metadata.

We also demonstrated the potential of HUNCOURT for scholarly research by putting forth methodological notes and preliminary results related to a substantive research agenda associated with the constitutional reasoning of the HCC. Through our initial research with HUNCOURT, we found that the HCC makes a more concerted effort to provide subtle interpretations for decisions of more elevated socio-economic-political or/and legal doctrinal significance. Finally, we also showed that a state-of-the-art database opens up possibilities for applying quantitative text analysis and text mining to research questions that have been only analysed in a qualitative framework.

Although it should be stressed that HUNCOURT can be continuously improved in the future, it is already clear from the results of our short pilot research presented in the article that it can be used to answer various research questions related to case law of the HCC, and that the developed research design can serve as a model for mapping constitutional case law in other jurisdictions.

Appendix

1The Hungarian version refers to the memorandum of the “law”, as this is what is used in practice. Yet in reality, the memorandum is associated with the bills.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article. Also, data files are available from OFS: https://osf.io/6aek9/?view_only=2234b78383064401afe9dbe5ab4aee1e.

Notes

See: Act CLI of 2011, on the Constitutional Court, Sect. 44. (2): “The decisions of the Constitutional Court shall be accessible for all in digital format on the website of the Office of the Constitutional Court, without identification, without restrictions and free of charge. For the publication of the decisions, the provisions on the publicity of judicial decisions of the Act on the Organisation and Administration of Courts shall be applied, as appropriate”. Based on Act CXII of 2011 on the right to informational self-determination and on the freedom of information, the Office of the Constitutional Court publishes data of public interest on its website at: alkotmanybirosag.hu. The English-language website address is: hunconcourt.hu.

We draw on philosophy and psychology to understand self-consciousness and self-reflection. In general, reflexive, reflexivity and reflexiveness describe the ability of language and thought to turn back on itself, to be an object to itself, and to refer to itself (Babcock, 1980). According to philosophy, self-consciousness is an awareness of oneself (Smith, 2020). Hegel believed that self-reflexivity is a fundamental principle of philosophy and determines rational thinking. He stated that life becomes more rational and self-determining when it becomes conscious and self-conscious (Houlgate, 2021).

COM(2021)118, Brussels, 9.3.2021. Source: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0118&from=hu

National Digitalisation Strategy (NDS) 2022–2030. Source: https://cdn.kormany.hu/uploads/document/6/60/602/60242669c9f12756a2b104f8295b866a8bb8f684.pdf

COM(2020) 710 final, Brussels, 2.12.2020. Source: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0710&from=HU

T/16118. Source: https://www.parlament.hu/irom41/16118/16118.html

See the explanatory note to T/16118. Source: https://www.parlament.hu/irom41/16118/adatok/fejezetek/03.pdf

See the explanatory note to T/152. Source: https://www.parlament.hu/irom42/00152/adatok/fejezetek/03.pdf

The source is a subscription-based Hungarian database of legal documents (https://uj.jogtar.hu/).

The full list of metadata variable is as follows: number of decision, title, year, text, citations that refer to a previous HCC decision or orders, citations in which the HCC does not refer to its own decision, but to a piece of legislation (Constitution, Fundamental Law, law, regulation), list of self-referencing document titles, list of externally-referred document titles, names of all judges who signed the decision, head judge, drafting judge, approving judges, dissenting judges, the type of the document (decision or order) and download link.

The data collection tasks were carried out following a login to a subscripted account on Jogtár. We started by utilising our source website’s internal search engine (https://uj.jogtar.hu/) for an API request of a table containing the list of internal document IDs as well as some metadata. This list of IDs could later be easily transformed into a list of links from where we can obtain the texts of laws and further metadata. Access to the decisions is available through the Jogtár service of Wolters Kluwer at: http://landing.wolterskluwer.hu/szakmai-jogtar-demo?utm_source=netjogtar&utm_medium=gtm_onpage&utm_campaign=netjogtarGTMajanlolink&utm_content=head_link. A quick registration allows for free access to the data for two weeks.

References

Aaken, A. van, & List, C. (2017). Deliberation and decision: Economics, constitutional theory and deliberative democracy (0 ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315258256

Altameem, T., Zairi, M., & Alshawi, S. (2006). Critical success factors of E-government: A proposed model for E-government implementation. Innovations in Information Technology, 2006, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/INNOVATIONS.2006.301974

Argyris, C. (1976). Single-loop and double-loop models in research on decision making. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(3), 363. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391848

Argyris, C. (1977). Double loop learning in organisations. Harvard Business Review, 55, 115–125.

Babcock, B. A. (1980). Reflexivity: Definitions and discriminations. Semiotica, 30(1–2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1980.30.1-2.1

Benoit, K., & Matsuo, A. (2022). Wrapper to the ‘spaCy’ ‘NLP’ Library. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/spacyr/spacyr.pdf

Boda, Z., & Sebők, M. (Eds.). (2018). A magyar közpolitikai napirend: Elméleti alapok, empírikus eredmények. MTA TK PTI.

Bodnár, E. (2021). The use of comparative law in the practice of the Hungarian Constitutional Court: An empirical analysis (1990–2019). Hungarian Journal of Legal Studies, 61(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1556/2052.2020.00306

Bolonyai, F., & Sebők, M. (2020). Kvantitativ szövegelemzés és szövegbányászat. In A. Jakab & M. Sebők (Eds.), Empirikus jogi kutatások: Paradigmák, módszertan, alkalmazási területek (pp. 361–380). Osiris Kiadó: MTA TársadalomtudományiKutatóközpont.

Boumans, J. W., & Trilling, D. (2016). Taking stock of the toolkit: An overview of relevant automated content analysis approaches and techniques for digital journalism scholars. Digital Journalism, 4(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2015.1096598

Chi, Y., Zhang, P., Wang, F., Lu, T., & Gu, N. (2022). Legal judgement prediction of sentence commutation with multi-document information. In Y. Sun, T. Lu, B. Cao, H. Fan, D. Liu, B. Du, & L. Gao (Eds.), Computer supported cooperative work and social computing (Vol. 1491, pp. 473–487). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4546-5_37

Coupette, C. (2019). Juristische Netzwerkforschung (p. 157012). Mohr Siebeck. https://doi.org/10.1628/978-3-16-157012-4

Cunliffe, A. L., & Jun, J. S. (2005). The need for reflexivity in public administration. Administration & Society, 37(2), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399704273209

Devins, C., Felin, T., Kauffman, S., & Koppl, R. (2017). The law and big data. Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, 27(2), 358–413.

Drinóczi, T., & Bień-Kacała, A. (2019). Illiberal constitutionalism: The case of Hungary and Poland. German Law Journal, 20(8), 1140–1166. https://doi.org/10.1017/glj.2019.83

Dyevre, A. (2020). Text-mining for lawyers: How machine learning techniques can advance our understanding of legal discourse. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3734430

Dyevre, A. (2021). The promise and pitfall of automated text-scaling techniques for the analysis of jurisprudential change. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 29(2), 239–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-020-09274-0

Farmer, D. J. (1995). The language of public administration: Bureaucracy, modernity, and postmodernity. University of Alabama Press.

Gárdos-Orosz, F., & Szente, Z. (Eds.). (2021). Populist challenges to constitutional interpretation in Europe and beyond. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Gárdos-Orosz, F., & Zakariás, K. (Eds.). (2021). Az alkotmánybírósági gyakorlat I-II. Az Alkotmánybíróság 100 elvi jelentőségű határozata, 1990–2020. Társadalomtudományi Kutatóközpont : HVG-ORAC Lap- és Könyvkiadó.

Garten, J., Kennedy, B., Sagae, K., & Dehghani, M. (2019). Measuring the importance of context when modeling language comprehension. Behavior Research Methods, 51(2), 480–492. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01200-w

Gil-García, J. R., & Pardo, T. A. (2005). E-government success factors: Mapping practical tools to theoretical foundations. Government Information Quarterly, 22(2), 187–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2005.02.001

Gregor, S., & Hevner, A. R. (2013). Positioning and presenting design science research for maximum impact. MIS Quarterly, 37(2), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.2.01

Grimmer, J., & Stewart, B. M. (2013). Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis, 21(3), 267–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps028

Halmai, G. (2019). Dismantling constitutional review in Hungary. Hrevista Di Diritti Comparati, 1, 31–47.

Harmon, M. M. (1995). Responsibility as paradox: A critique of rational discourse on government. Sage Publications.

Hess, T., Matt, C., Benlian, A., & Wiesböck, F. (2016). Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy [Application/pdf]. https://doi.org/10.7892/BORIS.105447

Hevner, M., & Park, & Ram. (2004). Design science in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 28(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148625

Homburg, V. (2008). Understanding e-government: Information systems in public administration. Routledge.

Horlacher, A., Klarner, P., & Hess, T. (2016). Crossing boundaries: Organization design parameters surrounding CDOs and their digital transformation activities. AMCIS 2016: Surfing the IT Innovation Wave - 22nd Americas Conference on Information Systems, 1, 1333–1342.

Houlgate, S. (2021). Hegel’s Aesthetics. In Z. Edward N. (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy ((Winter 2021 Edition)). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/hegel-aesthetics/

Jakab, A., Dyevre, A., & Itzcovich, G. (2015). CONREASON – The Comparative Constitutional Reasoning Project. Methodological Dilemmas and Project Desig. MTA Law Working Papers, 9, 1–24.

Jakab, A., Dyevre, A., & Itzcovich, G. (Eds.). (2017). Comparative Constitutional Reasoning (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316084281

Jakab, A., & Fröhlich, J. (2017). The Constitutional Court of Hungary. In A. Jakab, A. Dyevre, & G. Itzcovich (Eds.), Comparative constitutional reasoning (1st ed., pp. 394–437). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316084281.013

Jakab, A., & Kazai, V. Z. (2021). A Sólyom-bíróság hatása a magyar alkotmányjogi gondolkodásra. In T. Győrfi, V. Z. Kazai, & E. Orbán (Eds.), Kontextus által világosan: A Sólyom-bíróság antiformalista elemzése (pp. 115–137). L’Harmattan Kiadó.

Jakab, A., & Sebők, M. (Eds.). (2020). Empirikus jogi kutatások: Paradigmák, módszertan, alkalmazási területek. Osiris Kiadó: MTA TársadalomtudományiKutatóközpont.

Jonathan, G. M. (2020). Digital transformation in the public sector: Identifying critical success factors. In M. Themistocleous & M. Papadaki (Eds.), Information systems (Vol. 381, pp. 223–235). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44322-1_17

Kelemen, K. (2013). Dissenting opinions in constitutional courts. German Law Journal, 14(8), 1345–1371. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2071832200002297

Komárek, J. (2017). National constitutional courts in the European constitutional democracy: A rejoinder. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 15(3), 815–825. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mox052

Kovács, K., & Tóth, G. A. (2011). Hungary’s constitutional transformation. European Constitutional Law Review, 7(2), 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1574019611200038

Kowsrihawat, K., Vateekul, P., & Boonkwan, P. (2018). Predicting judicial decisions of criminal cases from Thai Supreme Court using bi-directional GRU with attention mechanism. 2018 5th Asian Conference on Defense Technology (ACDT), 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACDT.2018.8592948

Lage-Freitas, A., Allende-Cid, H., Santana, O., & Oliveira-Lage, L. (2022). Predicting Brazilian court decisions. PeerJ Computer Science, 8, e904. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.904

Matt, C., Hess, T., & Benlian, A. (2015). Digital transformation strategies. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 57(5), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-015-0401-5

Medvedeva, M., Vols, M., & Wieling, M. (2020). Using machine learning to predict decisions of the European Court of Human Rights. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 28(2), 237–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-019-09255-y

Medvedeva, M., Wieling, M., & Vols, M. (2023). Rethinking the field of automatic prediction of court decisions. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 31(1), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-021-09306-3

Mergel, I., Kattel, R., Lember, V., & McBride, K. (2018). Citizen-oriented digital transformation in the public sector. Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research: Governance in the Data Age, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1145/3209281.3209294

Mullen, A. L., Benoit, K., Keyes, O., Selivanov, D., & Arnold, J. (2018). Fast, consistent tokenization of natural language text. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(23), 655. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00655

Nyitrai, T. (2021). A gépi tanulás módszereinek alkalmazása R-ben. Statisztikai Szemle, 99(2), 173–198. https://doi.org/10.20311/stat2021.2.hu0173

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A., & Chatterjee, S. (2007). A design science research methodology for information systems research. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(3), 45–77. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222240302

Pócza, K. (2018). Constitutional politics and the judiciary: Decision-making in Central and Eastern Europe (K. Pócza, Ed.; 1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429467097

Pokol, B. (2002). Constitutionalization and political fighting through litigation. Jogelméleti Szemle, 1, 1–22.

Porter, M. F. (2001). Snowball: A language for stemming algorithms. http://snowball.tartarus.org/texts/introduction.html

Purao, S. (2002). Design research in the technology of information systems: Truth or dare. Working Paper, Department of Computer Information Systems, 34, 45–77.

Quinn, B. (2013). Reflexivity and education for public managers. Teaching Public Administration, 31(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739413478961

Sarwar, M. I., Abbas, Q., Alyas, T., Alzahrani, A., Alghamdi, T., & Alsaawy, Y. (2023). Digital transformation of public sector governance with IT service management–A pilot study. IEEE Access, 11, 6490–6512. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3237550

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Sebők, M., Gárdos-Orosz, F., Kiss, R., & Járay, I. (2023). The transparency of constitutional reasoning: A text mining analysis of the Hungarian Constitutional Court’s jurisprudence. (Manuscript).

Sebők, M., Ring, O., & Máté, Á. (2021). Szövegbányászat és mesterséges intelligencia R-ben. Typotex.

Sharma, S., Gamoura, S., Prasad, D., & Aneja, A. (2021a). Emerging legal informatics towards legal innovation: Current status and future challenges and opportunities. Legal Information Management, 21(3–4), 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1472669621000384

Sharma, S., Shandilya, R., & Sharma, S. (2022). Predicting Indian Supreme Court Judgments, Decisions, or Appeals. Statute Law Review, hmac006. https://doi.org/10.1093/slr/hmac006

Sharma, S., Sony, A. L., & R. (2021b). eLegalls: Enriching a legal justice system in the emerging legal informatics and legal tech era. International Journal of Legal Information, 49(1), 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/jli.2021.9

Shaughnessy, H. (2018). Creating digital transformation: Strategies and steps. Strategy & Leadership, 46(2), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-12-2017-0126

Smith, J. (2020). Self-Consciousness. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy ((Summer 2020 Edition)). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/self-consciousness/

Sólyom, L. (2015). The rise and decline of constitutional culture in Hungary. In A. von Bogdandy & P. Sonnevend (Eds.), Constitutional crisis in the European constitutional area: Theory, law and politics in Hungary and Romania (pp. 5–32). Hart/Beck. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474202176

Strickson, B., & De La Iglesia, B. (2020). Legal judgement prediction for UK courts. Proceedings of the 2020 The 3rd International Conference on Information Science and System, 204–209. https://doi.org/10.1145/3388176.3388183

Szente, Z. (2013). Hungary: Unsystematic and incoherent borrowing of law. The use of foreign judicial precedents in the jurisprudence of the constitutional court, 1999—2010. In T. Groppi & M.-C. Ponthoreau (Eds.), The use of foreign precedents by constitutional judges (pp. 253–272). Hart Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472561312

Tikk Domonkos. (2007). Szövegbányászat. Typotex.

Tonkin, E., & Tourte, G. J. L. (2016). Working with text: Tools, techniques and approaches for text mining (1st edition). Elsevier.

Tóth, G. A. (2019). Constitutional markers of authoritarianism. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 11(1), 37–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40803-018-0081-6

van Opijnen, M., Peruginelli, G., Kefali, E., & Palmirani, M. (2017). Online publication of court decisions in Europe. Legal Information Management, 17(3), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1472669617000299

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Sage Publications.

Weinshall, K., & Epstein, L. (2020). Developing high-quality data infrastructure for legal analytics: Introducing the Israeli Supreme Court Database. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 17(2), 416–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/jels.12250

Welbers, K., Van Atteveldt, W., & Benoit, K. (2017). Text analysis in R. Communication Methods and Measures, 11(4), 245–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2017.1387238

Whalen, R. (2016). Legal networks: The promises and challenges of legal network analysis. Michigan State Law Review, 539. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3000144

Zifcak, S. (1996). Hungary’s remarkable, radical, constitutional court. Journal of Constitutional Law in Eastern and Central Europe, 3(1), 1–56.

Ződi, Z. (2020). Az Alkotmánybírósági Ítéletek Hálózatának Elemzése. MTA Law Working Papers, 22, 1–37.

Ződi, Z., & Lőrincz, V. (2020). Az Alaptörvény és az alkotmánybírósági gyakorlat megjelenése a rendes bíróságok gyakorlatában, 2012–2016. In Normativitás és empíria: A rendes bíróságok és az alkotmánybíróság kapcsolata az alapjog-érvényesítésben, 2012–2016 (pp. 133–167). HVG-Orac. http://real.mtak.hu/118744/1/TK_JTI_normativitas_es_empiria.pdf

Acknowledgements

For their help in constructing the database and their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article, the authors thank Fruzsina Gárdos-Orosz, András Jakab and Zsolt Ződi. We would also like to thank Zoltán Kacsuk, Bálin György Kubik and Viktor Kovács for their technical suggestions and help regarding the database. We state that this project is fully independent from the Hungarian Constitutional Court.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Centre for Social Sciences. The research was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement no. 951832. The research was supported by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology NRDI Office within the framework of the Artificial Intelligence National Laboratory Programme. The project has received research funding and support from the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH). Grant title and number: “The Quality of Government and Public Policy: A Big Data Approach” (FK-123907). The project has received research funding and support from the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH). Grant title and number: “Reactivity of the Hungarian Legal System between 2010 and 2018” (FK-129018). Prepared with the professional support of the Doctoral Student Scholarship Program of the Co-Operative Doctoral Program of the Ministry of Culture and Innovation financed from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Statement for Journal of the Knowledge Economy

Hereby, I consciously assure that for the manuscript /insert title/the following is fulfilled:

-

1.

This material is the authors’ own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere.

-

2.

The paper is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

-

3.

The paper reflects the authors’ own research and analysis in a truthful and complete manner.

-

4.

The paper properly credits the meaningful contributions of co-authors and co-researchers.

-

5.

The results are appropriately placed in the context of prior and existing research.

-

6.

All sources used are properly disclosed (correct citation). Literally copying of text must be indicated as such by using quotation marks and giving proper reference.

-

7.

All authors have been personally and actively involved in substantial work leading to the paper and will take public responsibility for its content.

The violation of the Ethical Statement rules may result in severe consequences.

I agree with the above statements and declare that this submission follows the policies of Journal of the Knowledge Economy as outlined in the Guide for Authors and in the Ethical Statement.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Legal Informatics

Rights and permissions