Abstract

This study attempts to investigate the “dynamic IC transformation process” namely “knowledge inputs” → “processors” → “knowledge outputs” (I →P →O) model within the context of higher education institutes (HEIs) in Pakistan. In this knowledge era, HEIs are considered repositories of “knowledge” that are continuously reconfiguring and nurturing themselves with existing knowledge assets. Therefore, this study proposes a “dynamic IC transformation” (I →P →O) model to analyze the relationship between intellectual capital (IC) initiatives as “knowledge inputs” (I), “strategic innovation” and “process capabilities” as “processors” (P), and the performance of HEIs as “knowledge-outputs” (O). To test the model, we conducted a survey (questionnaire) involving 258 usable responses from teaching and non-teaching staff working in public and private HEIs in Pakistan. In this sense, we employed a parallel mediation analysis through process macro to evaluate the indirect effects of “processors” between “knowledge inputs” and “knowledge output.” The study identifies that “knowledge inputs” significantly influence the performance of HEIs in terms of “knowledge output.” However, the explanatory power of human capital as an essential element of IC initiatives is more detrimental than that of structural and relational capital initiatives. Further, results indicate that “processors,” i.e., “strategic innovation” and “process capabilities,” partially mediate the relationship between “knowledge inputs” and “knowledge output.” Thus, this study contributes to ongoing academic debates about how the “dynamic IC transformation model” works in producing “knowledge outputs” by leveraging “strategic innovation” and “process capabilities” of HEIs. Further, this study also offers fruitful implications for academicians that may turn the IC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” into the development of viable opportunities for HEIs as “entrepreneurial” or “stakeholder” universities by valuing their knowledge assets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research Background

In this era of intense competition, “knowledge assets,” commonly referred to as “Intellectual Capital” (IC) initiatives, are documented as the most valuable strategic resources to drive the “knowledge economy” (Singla et al., 2022; Dabić et al., 2020; Huang & Liu, 2005; Lev, 2001). Moving ahead, the investment in knowledge assets has increasingly been recognized as a source of value creation in knowledge-intensive subjects, especially in higher education institutions (HEIs), to lead the national innovation system and economic growth (OECD, 2020; Vo & Tran, 2022; Nicolò et al., 2021; Canibano et al., 2000; Secundo et al., 2016). These resources, which are valuable, rare, and unrivaled, provide a distinct source of competitive edge (Ferreira & Fernandes, 2017; Nicolò et al., 2021; Garde Sanchez et al., 2021; Drucker, 1994; Bontis, 1999). In the last few decades, HEIs have been primarily involved in the knowledge production process, with a prime focus on reinforcing the IC initiatives as “knowledge-input” to yield better performance from HEIs as “knowledge-output.” Prior research viewed IC initiatives as “knowledge-input” with various standpoints related to human, structural, and relational capital initiatives (Guerrero et al., 2021; Paoloni et al., 2021; Sánchez & Elena, 2006; Secundo et al., 2016; Arun & Shekar, 2020). Stewart (1997) asserted IC initiatives as intellectual knowledge embedded in human capital (experience and expertise), structural capital (systems and procedures), and relational capital (networking and relational ties). Nonetheless, IC initiatives cover all types of “knowledge inputs” (both explicit and tacit), which reside in the talents and skills of employees (human capital initiatives), systems and procedures (structural capital initiatives), and contacts and collaborations (relational capital initiatives) (Hayaeian et al., 2021; OECD, 2020; Córcoles et al., 2011; Arun & Shekar, 2020). These initiatives permit the “strategic innovation” and “process capabilities” of HEIs and subsequently improve the performance of HEIs (OECD, 2020; Vo & Tran, 2022; Krishna & Jain, 2020; Yoda & Kuwashima, 2020; Pedro et al., 2019; Nakamura, 1999). In addition, the recent paradigm shifts towards valuing “intangibles” have reshaped the traditional approaches of value creation towards a more innovative way of managing “knowledge-input” and “knowledge-output” in knowledge subjects (Hayaeian et al., 2021; Guerrero et al., 2021; Paoloni et al., 2021; Ferreira & Fernandes, 2017; Arun & Shekar, 2020; Baima et al., 2020).

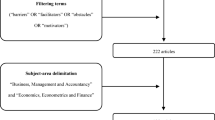

Since the 1990s, many corporate entities around the world have been adopting IC as a multidimensional phenomenon (Marr & Chatzkel, 2004; Lev, 2001). However, under the new paradigm of knowledge-intensive organizations, for instance, in HEIs, the appearance of IC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” has been widely recognized as an essential driver to lead the knowledge production process and national innovation system of a country (Cheng et al., 2022; Paoloni et al., 2021; Vo & Tran, 2022; Pedro et al., 2019; Matricano et al., 2020; Cricelli et al., 2018; Robertson et al., 2019; Agostini et al., 2017). In universities, both “knowledge inputs” and “knowledge outputs” are intangibles, and only a small part of studies reinforced the importance of IC initiatives with limited contexts and instruments (Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018; Canibano & Sanchez, 2004; Sanchez & Elena, 2006). However, as academic debates on IC initiatives have grown in recent years, there is now recognition of a need for the development of new appropriate mechanisms for its evaluation and measurement (Cheng et al., 2022; Arun & Shekar, 2020; Canibano & Sanchez, 2004; Sanchez & Elena, 2006). In such a manner, the conversion of “knowledge inputs” (I) into “knowledge outputs” (O) as a “dynamic IC transformation process” (see Fig. 1) led to the foundation of this study for further investigation by integrating the “strategic innovation” and “process capabilities” as “processors” (P) for better understanding and development of the model (Zapp, 2022; Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018; Ramírez et al., 2007; Córcoles et al., 2011; Huang and Huang, 2020).

Continuing in the same vein, recent explorations from emerging knowledge economies revealed that HEIs play a critical role in the “IC transformation process” to correspond to better socio-economic growth (Vo & Tran, 2022; Singla et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Rebés et al., 2021; Ngoc-Tan & Gregar, 2018; Moncayo–Martínez et al., 2020; Cricelli et al., 2018; Kohoutek et al., 2017). Similarly, to other knowledge-oriented economies, IC is essential in Pakistani HEIs for leveraging the skill-based knowledge economy to meet the growing needs of stakeholders such as the government, industry, and society. Therefore, what has been discussed so far shows that knowledge is solicited from many perspectives in HEIs, as they are epicenters of “knowledge assets” (Van Langenhove, 2021; Secundo et al., 2016; Adomavičiūtė 2018; Pedro et al., 2019; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011; Ortega, 2013), where several knowledge-based activities are evolved inside them to gauge the “knowledge inputs” into “knowledge outputs” (Guerrero et al., 2021; Perkmann & Walsh, 2007; Elena, 2004; Leitner, 2004; Fazlagic, 2005; Cañibano & Sánchez, 2008; Vidrascu, 2016; Stewart, 1997).

Drawing from the above academic debates, most scholars have documented IC as a multi-perspective phenomenon in terms of its valuation and relevance (Lev, 2001; Cuozzo et al., 2017; Edvinsson, 2013). However, little research is known about the “dynamic IC transformation process” as “knowledge inputs” (i.e., human, structural, and relational capital initiatives) into expected “knowledge-outputs” (performance of HEIs) (Guerrero et al., 2021; Nicolò et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018). A look at the previous literature on the same theme reveals that scholars have not paid enough attention to reinforce the importance of “strategic innovation” and “process capabilities” as mediators in the “dynamic IC transformation process” (Guerrero et al., 2021; Paoloni et al., 2021; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011). Hence, by assuming this dynamic view of IC, an exclusive conceptual (referring to Fig. 1) “knowledge inputs”→ “processors” → “knowledge outputs” (I →P →O) model is proposed, which will provide a holistic view to academicians while demising policies related to IC initiatives, particularly in the context of HEIs of Pakistan (Guerrero et al., 2021; Munjal et al., 2021; Ramírez et al., 2007).

The Gap in the Literature

More importantly, in this fast-paced and knowledge-based era, the role of HEIs has become rather challenging due to a growing number of factors, which include the following:

-

(1)

a greater level of corporate universities due to extended competition

-

(2)

increasing level of internationalization and commercialization of knowledge

-

(3)

pressure to harmonize the structures, systems, and process capabilities of HEIs at the indigenous level

-

(4)

research and education and

-

(5)

strategic innovations to meet the growing needs of stakeholders (Zapp. 2022; Vo & Tran, 2022; HEC, 2016; Ramírez et al., 2007; Leitner & Warden, 2004; Cricelli et al., 2018)

To cater these challenges, which are even more compelling for emerging economies, have a greater level of tangible resources and generally disregard the intangible ones, or “knowledge assets” (Cheng et al., 2022; Garde Sanchez et al., 2021; Maditinos et al., 2011; Ståhle & Bounfour, 2008; Kianto, 2007). Generally, HEIs are considered epicenters of knowledge resources where knowledge is produced, endorsed, and disseminated (Agostini et al., 2017; Sanchez & Elena, 2006). Based on these features, HEIs can play a notable role in socioeconomic development (Zapp, 2022; Secundo et al., 2016; Markman et al., 2005; Ahmad et al., 2018). In this sense, HEIs need to focus on publicizing and restructuring the basic parameters of tertiary education, which will intuitively foster the knowledge production process and capacity building of national IC (Paoloni et al., 2021; Vo & Tran, 2022; Ramírez et al., 2016; Cricelli et al., 2018; Aubert & Reiffers, 2003; Weber, 2011).

Even though both “knowledge inputs” and “knowledge outputs” are intangibles in knowledge subjects (HEIs), it is a bit difficult to measure them precisely (Guerrero et al., 2021; Paoloni et al., 2021; Canibano & Sanchez, 2004; Sánchez & Elena, 2006). Given the complexity and difficulty, their measurement requires adopting a most resilient approach for capturing the synergistic effects (Paoloni et al., 2021; Dumay, 2009; Edvinsson, 2013). In this sense, the “dynamic IC transformation process” (see Fig. 1) is very crucial to valorize “knowledge outputs” through commercialization (Guerrero et al., 2021; Secundo et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2012; Lu, 2012), which was hardly debated in prior academic circles in a holistic way (Guerrero et al., 2021; Nicolò et al., 2021; Ramírez et al., 2016). Based on the theoretical lens of the knowledge-based view (KBV), we believe that IC initiatives, for instance, administrative skills, research capabilities, academic excellence, quality assurance programs, and diverse academic collaborations, among others, will positively influence the performance of HEIs (Zapp, 2022; Guerrero et al., 2021; Serino et al., 2020; Cricelli et al., 2018; Carayannis et al., 2017; Scuotto et al., 2017). Hence, by assuming the existence of a “dynamic IC transformation process” in view of the theoretical underpinnings of KBV, it is true to say that IC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” are critical factors to correspond to the better performance of HEIs as “knowledge outputs” (Warden, 2004; Ramírez et al., 2016; Leitner, 2004).

Drawing from the previous studies done with a prime focus on the IC initiatives, it is possible to state that limited empirical studies have highlighted the role of IC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” on the performance of HEIs as “knowledge outputs” (Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018; Ramírez et al., 2007; Ramírez et al., 2016). However, this study, among others, accentuates the importance of the “dynamic IC transformation process” (see Fig. 1) in the field of HEIs by better reinforcing the mediating role of “strategic innovation” and “process capabilities” as “processors” (Guerrero et al., 2021). These aspirations pushed the authors to analyze whether and how “processors” can perform the bridging role in the “dynamic IC transformation process” (Ramírez et al., 2016; Sánchez & Elena, 2006), which remains sparse, particularly in the context of HEIs (Guerrero et al., 2021; Leitner, 2004; Cricelli et al., 2018).

Nonetheless, the accumulated literature on IC initiatives reveals that HEIs are known to be factories of knowledge production where knowledge evolves through technical know-how, experience and expertise, systematic research analyses, teaching pedagogies, and industry–university partnerships (Ramírez et al., 2016; Guerrero et al., 2021; Baima et al., 2020; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011), whereas “processors” as repetitive and dynamic activities of HEIs enable them to convert the “knowledge inputs” into “knowledge outputs” (Guerrero et al., 2021; Canibano & Sanchez, 2004; Sánchez & Elena, 2006). Further, after a comprehensive analysis of the literature, we found that only Guerrero et al. (2021) highlighted an urgent need for future studies with mediating roles of “processors” in the “dynamic IC transformation process” which was relatively untapped in the academic literature on IC. Therefore, this study is strongly inspired by this argument, and thus, directly responds to it.

Aim and Originality of the Study

Afterward, getting inspiration from the theoretical underpinning of the proposed “dynamic IC transformation process” (see Fig. 1), this study aimed to explore the relationship between IC initiatives (knowledge inputs) and performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs) through “processors” (strategic innovation and process capabilities) as intermediate measures (Guerrero et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2021; Rehman et al., 2022; Gold et al., 2001; Zack et al., 2009; Barney, 1991; Drucker, 1994). While keeping in mind, the growing importance of IC initiatives in knowledge subjects (HEIs), neither theoretically nor empirically, there is a dearth of research that evaluates the role of IC initiatives (i.e., human, structural, and relational capital) as nascent “knowledge inputs” in stimulating the performance of HEIs as “knowledge outputs” (Chen et al., 2021; Guerrero et al., 2021; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011; Córcoles et al., 2011). In this sense, Cricelli et al. (2018) argued that HEIs continuously reconfigure and nurture themselves by using “knowledge inputs” that are able to generate more “knowledge outputs” in the form of technical and scientific productions. Among others, Guerrero et al. (2021) pointed out the pivotal role of teaching staff expertise, skills, and competencies as important proponents of IC inputs in achieving a higher level of research and development as IC outputs. Nonetheless, Chen et al. (2021) illustrated that the operational excellence of HEIs is more likely to influence by the level of “knowledge inputs” (i.e., teaching and research). Therefore, in consequence of the asymmetry of relevant literature, this study focuses on the “dynamic IC transformation process,” namely “knowledge inputs” → “processors” → “knowledge outputs” (I →P →O) to provide valuable recommendations to academicians.

To continue in the same direction, this study views that HEIs’ capabilities to successfully transform valuable “knowledge inputs” into “knowledge output” are generally driven by their “processors” (Paoloni et al., 2021; Vo & Tran, 2022; Córcoles et al., 2011). Similarly, in other knowledge, productive organizations, “processors” refer to repeatable tasks, activities, or doing things innovatively to leverage the knowledge-production process in HEIs (Secundo et al., 2016; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011; Ramírez et al., 2007). Consistently, the importance of “processors” in transmitting knowledge is increasingly recognized in knowledge subjects (HEIs) to cater to the growing needs of stakeholders (Secundo et al., 2016; Cricelli et al., 2018; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011; Ramírez et al., 2007). Therefore, we assume that IC initiatives, as “knowledge inputs” (competencies, systems, strategic alliances, etc.), are constantly transformed into “knowledge outputs” (OECD, 2020; HEC, 2021) by better emphasizing their “strategic innovation” and “process capabilities.” Therefore, investigation of this holistic “knowledge inputs” → “processors” → “knowledge outputs as a “dynamic IC transformation process” (see Fig. 1) is very crucial for knowledge production, particularly in knowledge subjects (HEIs), which remains under research (Guerrero et al., 2021; Nicolò et al., 2021; Secundo et al., 2016). In particular, the relationship with “processors” as mediators is found inconsistent in academic debates (Salinas-Avila et al., 2020) and thus calls for shedding light on this new insight into the “dynamic IC transformation process” (Guerrero et al., 2021; Salinas-Avila et al., 2020; Petruzzelli et al., 2018; Kianto, 2007).

To achieve these objectives, we selected the HEIs of Pakistan as a suitable population because Pakistan’s economy is in a transition phase from low tertiary education enrollment, a high level of income inequality, poor health standards, and infrastructures into a knowledge economy supported by existing of IC initiatives as valuable knowledge resources (OECD, 2020; HEC, 2021). In Pakistan, HEIs are anticipating immense expectations from stakeholders to become more “entrepreneurial” and “stakeholder” universities to compete in indigenous and international markets (HEC, 2016; Clark, 1998; Leitner, 2004; Secundo et al., 2016). In this sense, they are continuously involved in restructuring the basic parameters of tertiary education due to the increasing level of internationalization and commercialization of knowledge resources (Paoloni et al., 2021; Guerrero et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2022; Cricelli et al., 2018; HEC, 2016).

In this regard, the Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan, being a regularity and supervisory authority, is continuously striving to introduce profound changes related to intangibles aimed at to bettering socio-economic growth (Vo & Tran, 2022), to strengthen the national IC, and thus enable it to be a more compelling place for the knowledge production process (Arun & Shekar, 2020; Yoda & Kuwashima, 2020). It is also pertinent to mention that currently, HEIs are facing acute budgetary cuts, thereby putting them in a more critical situation to achieve their desired objectives (HEC, 2016). Besides this, HEC has set innovative parameters to evaluate the performance of HEIs through links with research outputs, funding agreements, diverse academic collaborations, programs, and academic excellence initiatives (HEC, 2016; Hayaeian et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2022; Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018). In this sense, they need to adopt the comprehensive IC transformation models to attract more funds from donors, thus enabling them to uplift the performance of HEIs by ensuring performance evaluation standards (Chen et al., 2021).

Continued in the same direction, the improvements in IC’s initiatives are top agenda items in all medium-term development frameworks (MDTFs) of HEC (HEC, 2016). Similarly, to other productive organizations, HEC made significant efforts to improve the academic excellence, R&D, and entrepreneurial activities in HEIs of Pakistan (HEC, 2021; Guerrero et al., 2021; Vo & Tran, 2022; Zapp, 2022). The prime focus of HEC is the provision of quality education with equitable access (HEC, 2021). Consistently, one of the important pillars of MTDF-II that encouraged IC initiatives to bring the industry-government-society even closer to academia is strategic innovation and resource building of inter-intra process capabilities of HEIs (HEC, 2021; Guerrero et al., 2021; Singla et al., 2022; Cricelli et al., 2018). Therefore, the greater agility and resilience of HEIs towards academic diversification, excellent research, competitiveness, and strategic liaisons at indigenous and international levels will be the cornerstones of improving their performance to anticipate the growing needs of stakeholders (HEC, 2021; Vo & Tran, 2022; Chen et al., 2021; Nicolò et al., 2021; Guerrero et al., 2021).

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

IC initiatives commonly referred to as “knowledge inputs” offer a richness of perspective and relevance in the field of KBV (Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018; Bontis, 1999; Gold et al., 2001; Mills & Smith, 2011; Galati et al., 2017), while the nuance “knowledge inputs” in the context of HEIs are used interchangeably with “IC initiatives” (Paoloni et al., 2021; Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018). Several studies provide convincing arguments and conceptions regarding the acceptability of IC initiatives in the context of HEIs (Secundo et al., 2016; Bucheli et al., 2012). Consistently, studies have classified “knowledge inputs” as IC initiatives into human capital initiatives (e.g., learning and education, experience, and expertise of teaching and non-teaching staff), structural capital initiatives (e.g., systems and programs, research and development, intellectual property rights, etc.), and relational capital initiatives (e.g., strategic alliances, licensing and agreements, stakeholders’ knowledge, etc.) (Guerrero et al., 2021; Sharabati et al., 2010; Bontis, 1999; Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Feng et al., 2012; Sánchez & Elena, 2006; Secundo et al., 2016; Bucheli et al., 2012; Córcoles et al., 2011).

The performance of HEIs is commonly attributed to “knowledge outputs” which can be assessed by investing in critical strands of IC such as human, structural, and relational capital (Guerrero et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2022; Sánchez & Elena, 2006; Elena, 2004; Wu et al., 2012). Most recently, the analysis of the literature revealed that the performance of HEIs relied importantly on IC initiatives that took place inside them (Paoloni et al., 2021; Singla et al., 2022; Guerrero et al., 2021; Vrontis et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018). These initiatives significantly influence the performance of HEIs by reinforcing the increasing importance of scientific and technical production and diverse academic collaborations with stakeholders (Dezi et al., 2019; Kivistö et al., 2019; Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018).

Human capital (HC) is considered an essential element of IC initiatives, constantly involved in the knowledge production process (O’Neill and Bagchi-Sen, 2020; Cricelli et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2021). It is the most valuable strategic resource that drives the knowledge economy and subsequently positively influences the performance of knowledge subjects (O’Neill and Bagchi-Sen, 2020; Paoloni et al., 2021; Smidova, 2019; Chatterji & Kiran, 2017). It encompasses the knowledge, skills, and intellectual abilities of teaching and non-teaching staff (Chen et al., 2021; Seleim et al., 2004; Ramírez & Gordillo, 2014; Zlate & Enache, 2015). Professors, academicians, research scholars, administrative staff, and students, in general, are considered important strands of HC in universities (Cricelli et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2021). In this sense, faculty development initiatives such as training, expanding access to higher education, learning, and greater mobility of faculty and staff are paramount for human capital formation in HEIs (Benneworth & Nieth, 2020; Brennan & Cochrane, 2019). These initiatives are increasingly recognized as “knowledge inputs” that may improve the performance of HEIs as “knowledge outputs” (O’Neill and Bagchi-Sen, 2020; Ramírez & Gordillo, 2014; Cricelli et al., 2018; Casanueva & Gallego, 2010).

From this perspective, HC initiatives reside in the teaching, research, and administrative capabilities of teaching and non-teaching staff (Cricelli et al., 2018). Prior research suggested that HC initiatives enhance the cognitive agility, skill, competence, and productivity of knowledge workers, when they exchange knowledge with each other (Zambon, 2002; Davidsson & Honig, 2003). By assuming this dynamic view of the IC transformation process (Guerrero et al., 2021), we argue that a greater level of HC initiatives (knowledge inputs) positively influences the performance of HEIs as “knowledge outputs” (Chatterji & Kiran, 2017; Kidwell et al., 2000). We can propose the following hypothesis based on these arguments: knowledge inputs → knowledge outputs.

-

H1. In the dynamic IC transformation process, HC initiatives (knowledge inputs) improve the performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs).

Structural capital (SC) covers non-human capital or repositories of knowledge resources embedded in organization systems, structures, databases, programs, procedures, charts, etc. (Andreeva et al., 2021; Barrena-Martínez et al., 2020; Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Choo & Bontis, 2002; Bontis et al., 2002). Unlike HC, SC generally resides in the organization’s systems, culture, infrastructure, databases, and innovative procedures (Bontis et al., 2002), which provide innovative ways to look at things differently (Leitner, 2004; Chahal & Bakshi, 2015). It remains in the organization even if employees leave it at the day’s end (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Bontis, 2003). Therefore, SC initiatives are considered valuable “knowledge inputs” to augment the performance of the organization (Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018; Itami, 1987). However, organizations with a feeble SC have difficulty reaching their potential (Chahal & Bakshi, 2015; Cricelli et al., 2018).

Given that, the SC of universities is typically associated with “knowledge inputs” that arise from internal systems, structures, and databases (Noel & Finocchio, 2022; Cricelli et al., 2018; Sharabati et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2012; Ramírez et al., 2007; Lu, 2012). It also presents explicit knowledge codified within the archives, bibliographic, and documentary resources of universities, to mobilize the internal production and management of scientific research outputs and valuing of innovative knowledge through commercialization (Nicolò et al., 2021; Aversano et al., 2020). Nonetheless, the intrinsic value of SC initiatives can be recognized from universities’ internal management support systems, the procedure for obtaining accreditations and certifications, and diverse academic programs (Noel & Finocchio, 2022; Nicolò et al., 2020; Córcoles et al., 2011; Cricelli et al., 2018). Hence, the performance of HEIs can be assessed by leveraging the level of SC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” (Noel & Finocchio, 2022; Nicolo, 2020; Córcoles et al., 2011). From that perspective, effective implementation of SC initiatives, for instance, will reduce the knowledge barriers and fill the gap between knowledge production and dissemination to yield higher performance in HEIs (Arun & Shekar, 2020; Cañibano & Sánchez, 2008). Hence, based on these motivations, we proposed the following hypothesis, considering SC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” to lead the performance of HEIs as “knowledge outputs.”

-

H2. In the dynamic IC transformation process, SC initiatives (knowledge inputs) improve the performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs).

Relational capital (RC) is commonly defined as knowledge embedded in relationships with stakeholders such as customers, suppliers, regulators, communities, pressure groups, and intermediaries (Roos et al., 1997; Vrontis et al., 2021; Cosma et al., 2019; Bontis, 1999). RC is a valuable knowledge resource that contributes to creating value and leading the overall performance and success of the organization (Abd-Elrahman and Kamal, 2020; Catanzaro et al., 2019; Kohtamäki et al., 2012). Owing to such positive interrelatedness, prior research has shown that the extent of mutual trust, licensing agreements, and formal contracts with third parties facilitates the knowledge integration process (Zahoor & Gerged, 2021; Bhatti et al., 2020; Roos et al., 1997) and consequently leads the performance of the organization (Yayla et al., 2018; Hult et al., 2004). Consistent with these notations, Yoo et al. (2016) asserted that close interactions and a reciprocal flow of knowledge among strategic partners positively influence the performance of the organization. Thus, relationships established with the external environment are proven to “knowledge inputs” and integration (Zahoor & Gerged, 2021).

Continuing in the same direction, RC in HEIs is symbolized as “far-reaching closeness and mutual integration upheld between universities and their academic and non-academic partners” (Córcoles et al., 2011, p.360). It also refers to the perception of others about university graduates’ employability and relations with business enterprises (Paoloni et al., 2021; Ramírez et al., 2007; Secundo et al., 2015). In this sense, universities’ well-matured contacts with stakeholders are essential for the formation of the potential of RC (Paoloni et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2012). However, research on how the potential of RC can influence the IC transformation process to leverage better “knowledge outputs” has been limited to date (Guerrero et al., 2021). Since RC ascertains the ability of HEIs to gain “knowledge inputs” by establishing relations with stakeholders (students, society, government, and industry) (Guerrero et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2020; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011). Therefore, it can be deemed a vital source to foster the performance of HEIs, specifically in facilitating “knowledge outputs” by reinforcing research and commercialization of innovative knowledge (Bontis, 1998; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011). We accordingly hypothesized that a greater level of universities’ diverse relations (MOUs), joint projects, graduate employability, participation, and hosting of conferences, etc. tends to foster the performance of HEIs (González & Rodríguez, 2010; Sánchez & Elena, 2006; Bezhani, 2010; Leitner, 2004).

-

H3. In the dynamic IC transformation process, RC initiatives (knowledge inputs) improve the performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs).

HEIs significantly contribute to strengthening the national innovation system of a country (Yoda & Kuwashima, 2020; Nelson & Rosenberg, 1993). Therefore, strategic innovation is a critical factor in knowledge subjects, especially in HEIs that drive the knowledge economy (Yoda & Kuwashima, 2020; Vo & Tran, 2022). Prior research affirmed that strategic innovation (SI) refers to the materialization of unique ideas through employees’ creativity and the perpetual innovation process (Matricano et al., 2020; Agostini, et al., 2017; Cabrilo et al., 2018; European Commission, 2006). In this regard, faculty and staff independence in academic meetings, the allocation of significant funds for R&D, the efficient launch of innovative procedures, and systems for scientific productions and collaborations are critical strands of strategic innovation to foster the “knowledge outputs” process in HEIs (Vo & Tran, 2022; Guerrero et al., 2021; Nicolò et al., 2021; Wu, et al., 2010; Maritz, 2010; Nwagwu, 2008; OECD, 2019).

Notwithstanding, strategic innovation leads to the “knowledge outputs” process in HEIs (Cricelli et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2021), which remains under-researched so far (Yoda & Kuwashima, 2020). Furthermore, the accumulated literature shows the lack of an explicit focus on the relationship between strategic innovation and the performance of HEIs as knowledge outputs. As a result, we speculate whether and how this relationship can aid in determining HEIs’ strategic innovative capability to valorize knowledge via the dynamic IC transformation process, which is heavily influenced by HEI knowledge process capabilities (Krishna & Jain, 2020; Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000; Cañibano & Sánchez, 2008; Cavagnoli, 2011). In this sense, we could be able to determine the crowding-out effects of strategic innovation on the performance of HEIs through the appropriate utilization of knowledge resources, the efficient launch of innovative programs, and the utilization of external funds for developing R&D activities (Guerrero et al., 2021; Chesbrough et al., 2018). According to this viewpoint, strategic innovation activities in HEIs reduce fixed costs and increase the likelihood of achieving R&D goals (Nicolò et al., 2021; Cuozzo et al., 2017), which leads to HEI performance in terms of leveraging scientific and technical productions, collaborations, and the number of graduates and doctoral produced (Leitner, 2004; Ramírez et al., 2007; Cricelli et al., 2018; Cabrilo et al., 2018). Therefore, we hypothesized this relationship as follows:

-

H4. The greater the proclivity of HEIs toward strategic innovation, the better their performance (knowledge outputs).

One of the critical strands for valuing the performance of HEIs is first the adequacy of HC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” with expected goals to foster research outputs, knowledge process capabilities, and entrepreneurial spirits through establishing incubation centers (Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2021; Kivistö et al., 2019; Rehman et al., 2022). Generally, the HC of HEIs refers to faculty, students, research scholars, and administrative staff who are rigorously involved in the knowledge production process within the context of universities (Secundo et al., 2016; Guerrero et al., 2021). Therefore, Cricelli et al. (2018) pointed out that HEIs are the podiums of knowledge resources where implicit knowledge can be transformed into applicative knowledge (i.e., explicit knowledge) through the IC transformation process. The analysis of the literature shows that faculty, research scholars, and non-teaching staff are valuable human resources for HEIs (Cricelli et al., 2018; Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Cañibano & Sanchez, 2008). In this view, HC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” in the form of training and development, continuous learning, and staff mobility for higher education tend to stimulate the creativity, problem-solving skills, and intellectual agility of employees to do things differently, consequently leading the performance of HEIs (Paoloni et al., 2021; Matricano et al., 2020; Guerrero et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021). Based on the above discussion, we found that several studies have dealt with the performance of HEIs (Silvestri & Veltri, 2011; Cricelli et al., 2018; Córcoles et al., 2011). To date, very few studies have investigated the role of HC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” with strategic innovation as a mediator in the “dynamic IC transformation process” (Guerrero et al., 2021). Hence, this novel argument leads to the following hypotheses:

-

H5. In the dynamic IC transformation process, HC initiatives (knowledge inputs) have a positive effect on strategic innovation.

-

H6. Strategic innovation mediates the relationship between HC initiatives (knowledge inputs) and the performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs) in the dynamic IC transformation process.

Generally, SC denotes explicit knowledge embedded in manuals, processes, databases, and organizational culture (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 2000). Prior research viewed the explicit knowledge embedded in organizational structures and systems as being configured in such a way as to lead the innovative process (Beltramino et al., 2020; Dierkes et al., 2003; Leitner, 2004; Ramírez et al., 2007; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). While referring to the SC in HEIs, it is acknowledged as scientific and technical knowledge encoded in the value system of HEIs (Matricano et al., 2020). In addition, it takes into consideration the all types of programs related to academic excellence and quality assurance as well as procedures for monitoring IPRs, accreditations, and certifications (Vo & Tran, 2022; Nicolò et al., 2021). At the same time, Ramírez et al. (2016) described that SC is also comprised of technological resources, for instance, databases, documentary and bibliographical resources, and archives of IPRs. While keeping in mind the varying degree of importance of SC within HEIs, the analysis of the literature reveals that cultural cohesion, comprehensive recruitment and training programs, and procedures for diverse academic certifications are the essential strands of SC initiatives to lead the strategic innovation process in HEIs (Beltramino et al., 2020; Cabrilo & Dahms, 2018; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). Nonetheless, such initiatives not only enhance the innovative capability of HEIs but also enable them to transform individual knowledge into collective knowledge for leveraging the superior performance of HEIs (Matricano et al., 2020; Moncayo–Martínez et al., 2020; Cricelli et al., 2018), while prior studies on the same theme reveal that scholars have not paid enough attention to know whether and how strategic innovation (i.e., processors) works in the “dynamic IC transformation process” to improve the performance of HEIs (Matricano et al., 2020; Guerrero et al., 2021). To fill this gap, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

H7. In the dynamic IC transformation process, SC initiatives (knowledge inputs) have a positive effect on strategic innovation.

-

H8. In the dynamic IC transformation process, SC innovation mediates the relationship between SC initiatives (knowledge inputs) and the performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs).

Relation capital (RC) refers to the value-added relationship of firms to leverage the strategic innovation process in HEIs (Abd-Elrahman and Kamal, 2020; Cabrilo, et al., 2018; Tseng & Goo, 2005). Prior research has shown that the knowledge production process cannot work in isolation (Cricelli et al., 2018; Ramírez & Gordillo, 2014). In this sense, HEIs’s collaborations with the external environment accentuate the transformation of knowledge into products and processes that can be commercially exploited (Matricano et al., 2020; Robertson et al., 2019; Singla et al., 2022). In this regard, the potential of RC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” relying on various external relations with stakeholders (i.e., industry-government-society) advances the innovation process in HEIs (Silvestri & Veltri, 2011; Vrontis et al., 2021; Cosma et al., 2019). Edvinsson (2002) asserted that an organization operates in a dynamic environment, where RC is considered one of the most valuable facets to foster creativity and entrepreneurial spirits among knowledge workers (Hayaeian et al., 2021; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011; Ramírez et al., 2007). In this line, Guerrero et al. (2021) affirmed that university consultations with outside stakeholders (industry-government-society) are a complementary source of “knowledge inputs” to assist the growth of strategic innovation in HEIs. In this way, HEIs will optimally produce “knowledge outputs” by pursuing cooperation with stakeholders and the commercialization of knowledge resources as significant drivers to foster the performance of HEIs (Matricano et al., 2020; Yoda & Kuwashima, 2020; Nelson & Rosenberg 1993; Carayannis & Campbell 2009; Leitner, 2004). The previous literature is very interested in how universities collaborate with academic and non-academic partners to supplement the innovation process in HEIs (Krishna & Jain, 2020; Bezhani, 2010; González & Rodríguez, 2010). In this respect, Cai and Liu (2015) recommended that education and research activities in HEIs be closely linked with industrial innovation to advance the knowledge economy. Although, most empirical studies concentrate on the role of RC initiatives on universities’ performance and productivity (Nicolò et al., 2021; Paoloni et al., 2021; Ngoc-Tan & Gregar, 2018). However, minimal efforts were made to investigate the mediating role of strategic innovation in the “dynamic IC transformation process” to leverage the higher “knowledge outputs,” especially in the context of HEIs (Cricelli et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2021). To this aim, we propose how effective utilization of RC will offer better opportunities to lead the strategic innovation and “knowledge outputs” processes in HEIs (Yoda & Kuwashima, 2020; Huang and Huang, 2020; Bontis, 1998; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011).

-

H9. In the dynamic IC transformation process, RC initiatives (knowledge inputs) have a positive effect on strategic innovation.

-

H10. In the dynamic IC transformation process, strategic innovation mediates the relationship between RC initiatives (knowledge inputs) and the performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs).

Process capabilities refer to repeatable tasks, actions, or activities used to transform the “knowledge inputs” into “knowledge outputs” (Paoloni et al., 2021; Thrassou et al., 2020; Day, 1994; Wade & Hulland, 2004). Prior research denotes that knowledge resources work together with the process capabilities of the organization (Nicolò et al., 2021; Baima et al., 2020; Maritan & Peteraf, 2011; Sánchez et al., 1996; Stalk et al., 1992). Generally, process capabilities denote “processors” (see Fig. 1) that assist to manage, collate, and align the knowledge resources of the organization in the “dynamic IC transformation process” (Paoloni et al., 2021; Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018; Teece, 2007; Ferreira & Fernandes, 2017; Ferreira et al., 2018). HEIs have received due diligence attention in recent years due to their rigorous involvement in the knowledge production process (Paoloni et al., 2021; Vo & Tran, 2022; Arun & Shekar, 2020; Zapp, 2022). They are continuously involved in strengthening their inter-intra process capabilities by imparting quality education and research activities to students and faculty (Silvestri & Veltri, 2011; Cricelli et al., 2018), to valorize the “knowledge outputs” (Guerrero et al., 2021; Nicolò et al., 2021). This implies that diversification in IC initiatives at the indigenous and international levels tends to strengthen the process capabilities of HEIs (Cheng et al., 2022; Dasborough et al., 2015), consequently leading to the performance of HEIs (Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018; Córcoles et al., 2011; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011). Silvestri and Veltri (2011) asserted that process capabilities are crucial enablers of acquiring knowledge through internal structures and systems to cope with the emerging needs of stakeholders by offering market-oriented degree programs, the ability to develop strategic alliances, and facilitating wide information integration. However, little is known about the role of process capabilities in the “dynamic IC transformation process” (see Fig. 1) to achieve higher “knowledge outputs.” Keeping this in view, we assume that the potential of inter-intra process capabilities turns to improve the performance of HEIs by collating, renewing, and developing strategies related to knowledge resources (Dezi et al., 2019; Hayaeian et al., 2021; Mills & Smith, 2011; Miles & Clieaf, 2017). Based on this gap in the literature, we hypothesize the following relationship:

-

H11. In the dynamic IC transformation process, process capabilities (processors) have a positive effect on the performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs).

HC refers to the knowledge, skills, and intellectual abilities of teaching and non-teaching staff (Matricano et al., 2020; Guerrero et al., 2021; Ramírez & Gordillo, 2014). It comprises all people, such as faculty, administration, and students, who are constantly involved in several repeatable tasks and activities for knowledge production and dissemination (Hayaeian et al., 2021; Secundo et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2012; Cricelli et al., 2018). Prior research consistently demonstrated that HC initiatives aid in strengthening HEIs’ internal and external process capabilities, allowing them to make effective decisions to leverage HEI performance (Zahoor & Gerged, 2021; Bhatti et al., 2020; Kidwell et al., 2000). Consistent with this notation, Ramírez and Gordillo (2014) affirmed that faculty and student participation in academic meetings assists in transmitting implicit knowledge into explicit knowledge, successively enabling the process capabilities of HEIs. Although, HC initiatives are specifically intended to improve the internal structure and system of HEIs to cope with the external environment (Arun & Shekar, 2020; Garde Sanchez et al., 2021). Relationships with “process capabilities” as mediators are inconsistently found in academic debates (Salinas-Avila et al., 2020). To date, not enough attention has been paid to ascertain whether and how to process capabilities perform the bridging role in the “dynamic IC transformation process” (Ramírez et al., 2016; Sánchez & Elena, 2006), which remains sparse, particularly in the context of HEIs (Guerrero et al., 2021; Leitner, 2004; Cricelli et al., 2018). In this sense, we assume that teaching and non-teaching staff are “loci” of knowledge resources, primarily involved in the “dynamic IC transformation process” (see Fig. 1) to strengthen the process capabilities of HEIs, and subsequently lead the performance of HEIs (Guerrero et al., 2021). Based on these arguments, this study proposes the following hypotheses to test the relationship:

-

H12. In the dynamic IC transformation process, HC initiatives (knowledge inputs) have a positive effect on the process capabilities (processors) of HEIs.

-

H13. Process capabilities (processors) mediate the relationship between HC initiatives (knowledge inputs) and the performance of HEIs (knowledge outs).

Structural capital (SC) refers to non-human capital (organizational culture, supportive infrastructure, technological processes, etc.) used to enhance the efficiency and productivity of an organization and achieve its desired goals (Cricelli et al., 2018; Cheng et al., 2022; Bontis et al., 2000; Chahal & Bakshi, 2015). Arun and Shekar (2020) affirmed that effective structural capital determines the internal process capabilities, reduces the knowledge barriers, and fills the gap between knowledge production and transmission. Itami (1987) pointed out, as a whole SC initiative that is generally used to enhance the process capabilities to cope with the environment (external opportunities and challenges), ascertain the decision-making process, and determine the firm’s value system by encouraging organizational performance (Hayaeian et al., 2021; Paoloni et al., 2021; Zahoor & Gerged, 2021; Secundo et al., 2016). Continuing in the same direction, SC refers to the process of acquiring knowledge through internal processes that could enhance the spanning capabilities of HEIs (Baima et al., 2020; Huang and Huang, 2020; Cricelli et al., 2018; Secundo et al., 2016). Nonetheless, a strong SC establishes HEIs’ capacity to compete with the external environment and determines their capability to adapt to market changes quickly (Huang and Huang, 2020; Cricelli et al., 2018; Canibano & Sanchez, 2004; Sanchez & Elena, 2006), while the analysis of the literature shows that little is known about the crucial role of process capabilities as “processors” in the knowledge conversion process, particularly in HEIs (Ramírez & Gordillo, 2014; Paoloni et al., 2021; Guerrero et al., 2021). To this end, contemporary universities need to assess the role of process capabilities in the “dynamic IC transformation process” which is relatively untapped in the academic literature on IC. To fill this gap, we assume the following hypotheses:

-

H14. In the dynamic IC transformation process, SC initiatives (knowledge inputs) have a positive effect on the process capabilities (processors) of HEIs.

-

H15. Process capabilities (processors) mediate the relationship between SC initiatives (knowledge inputs) and the performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs).

RC refers to establishing close relations with internal and external partners (Alcaniz et al., 2011; Ferraris et al., 2020; Catanzaro et al., 2019). To this aim, process capabilities could perform a pivotal role in nurturing close relational ties to anticipate market demands quickly (Hayaeian et al., 2021; Arun & Shekar, 2020; Cricelli et al., 2018; Helfat & Peteraf, 2015; Teece, 2007). Generally, with strong internal process capabilities, an organization can pursue market changes rapidly, while developing their strategic posture (Huang and Huang, 2020; Day, 1994; Ferreira & Fernandes, 2017; Gold et al., 2001; Stalk et al., 1992). In HEIs, the knowledge conversion process cannot work without establishing strong relational ties with academic and non-academic partners (Zahoor & Gerged, 2021; Chatterji & Kiran, 2017; Yayla et al., 2018). Such relational ties among stakeholders provide the opportunity for sharing knowledge inputs, for instance, know-how, capabilities, and competencies for achieving R&D goals (Guerrero et al., 2021; Guerrero et al., 2019; Carayannis et al., 2000). This indicates that strong relational ties enable the process capabilities of HEIs to cater to the labor market demands by offering market-oriented degree programs and better services to industry, society, and regulators (Córcoles et al., 2011; Yayla et al., 2018). For all these reasons, the present study aims to contribute to the debate on RC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” through this research by leveraging the mediating role of “process capabilities” for the IC-driven performance of HEIs. Although the university’s collaborative initiatives are paramount to influencing the knowledge conversion process (Guerrero et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018; Yayla et al., 2018). To this end, little is known about how RC initiatives will be more successful in leveraging “process capabilities” within HEIs to generate more “knowledge outputs” (Guerrero et al., 2021; Guerrero et al., 2019). In this regard, the accumulated literature on RC (knowledge inputs) shows the lack of an explicit focus on “process capabilities” as a mediator in the “dynamic IC transformation process” (Guerrero et al., 2021; Zahoor & Gerged, 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018). By assuming the existence of process capabilities as “processors” within collaborative ties of universities with stakeholders, we suppose the following hypotheses to support the relationship of “knowledge inputs”→ “processes” → “knowledge outputs” (I →P →O).

-

H16. In the dynamic IC transformation process, RC initiatives (knowledge inputs) have a positive effect on the process capabilities (processors) of HEIs.

-

H17. Process capabilities (processors) mediate the relationship between RC initiatives (knowledge inputs) and the performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs).

Methodology

Drawing the impulse motivation from the proposed “dynamic IC transformation process” (see Fig. 1) (Guerrero et al., 2021; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011; Leitner, 2004; Ramírez et al., 2007; Cricelli et al., 2018), we acknowledged the HEIs as a system (repositories of IC resources) that continuously reconfigures and nurtures itself through presence of “knowledge inputs” (IC initiatives) to yield the “knowledge outputs” (performance of HEIs) (Paoloni et al., 2021; Arun & Shekar, 2020; Elena, 2004; Leitner, 2004; Cricelli et al., 2018; Córcoles et al., 2011). In addition, this system rigorously involves knowledge production, dissemination, and its valorization through commercialization (Rodríguez-Rebés et al., 2021; Córcoles, et al., 2011; Feng et al., 2012). In this sense, HEIs’s capability to “innovate” and “process capabilities” immensely relies on the effective utilization of IC resources to cater for the better performance of HEIs (Nicolò et al., 2021; Garde Sanchez et al., 2021; Nguyen, 2018; Tidd et al., 2005; Leitner, 2004; Ramírez et al., 2007). Therefore, the selected model enables us to understand the nature of the relationship between IC initiatives (human, structural, and relational capital) as “knowledge inputs” able to generate the performance of HEIs (technical and scientific research publications, valorization of knowledge through commercialization, IPR produces, entrepreneurial spirits, etc.) as “knowledge outputs” using the mediating role of strategic innovation and process capabilities as “processes” of HEIs (see Fig. 2).

Instrumentation and Measure Development Process

To analyze the underlying relationship (see Fig. 2), we proposed the “dynamic IC transformation process” using the “strategic innovation” and “process capabilities” as intermediate measures to evaluate the impact of IC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” on the performance of HEIs as “knowledge outputs.” This process involves five steps (described below) including the scale modification to scale development, encompassing several sets of procedures like a perceptual mapping of a scale to set the evidence free from common method and non-response biases (Shewchuk et al., 2005).

-

Step 1. Identification of the most suitable and appropriate items from the literature for scale modification related to IC initiatives (i.e., human, structural, and relational capital), strategic innovation, and process capabilities

-

Step 2. Generation of preliminary instruments pertaining to HEIs’ performance indicators for scale development

-

Step 3. Re-modification of the instrument based on the expert review feedback

-

Step 4. Pre-testation, sampling strategy, data collection, and

-

Step 5. Non-response and common method bias

In the first step, a modified scale for (I-P) was anchored to examine the relationship between “knowledge inputs” (I) (i.e., IC’s elements) and “processes” (P) (i.e., strategic innovation and process capabilities). As a perceptual assessment, we identified the thirty most appropriate and suitable items pertaining to IC covering all three elements (i.e., human, structural, and relational capital) from the work of Guerrero et al. (2021), Ramírez et al. (2016), Sharabati et al. (2010), Secundo et al. (2016), Feng et al. (2012), Leitner (2004), and Lu (2012); nine-item scale related to strategic innovation from the studies of Cheng et al. (2022), Subramaniam and Youndt (2005), Dumay and Garanina (2013), Wu et al. (2008), and Alpkan et al. (2010); and eleven-item scale was drawn to measure the process capabilities from the work of Day (1994) and Wade and Hulland (2004) as HEIs are playing an essential role towards in expanding and strengthening the higher education system to shape the knowledge economy in Pakistan. However, much of the IC initiative in corporate entities is firm and industry-specific (e.g., pharmaceutical, banking, hotel, healthcare, automotive, telecommunications, tourism sector, etc.) whereas assessing the propensity of IC initiatives in the context of HEIs is still sparse. As a result, to capture the recent trends in underlying research, minor modifications in scale were made in view of the theoretical lens of KBV (Cricelli et al., 2018; Guerrero et al., 2021; Ramírez et al., 2007; Córcoles et al., 2011) and HEI practices related to IC implementation initiatives, strategic innovation, and process capabilities.

In the second step, a self-developed scale was anchored to evaluate the performance of HEIs in Pakistan. The foremost objective for developing a new scale is that existing scales are obscure and were not precisely designed based on important performance indicators of HEIs such as research outputs, entrepreneurship, commercialization of knowledge, knowledge process capabilities, quality assurance, equitable access to education, academic collaboration, and linkages, specifically in the context of emerging economies (Cricelli et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2012; Córcoles et al., 2011; Elena, 2004; Sánchez & Elena, 2006). Therefore, we treated the performance of HEIs as a multi-dimensional construct, and its evaluation requires ascertaining the appropriate indicators (Guerrero et al., 2021; Paoloni et al., 2021; Marr & Chatzkel, 2004; Lev, 2001). Moreover, for achieving better economic benefits and advancement, assessing the IC initiatives in HEIs is one of the most critical steps toward the systemic evaluation of the performance of HEIs (Nicolò et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018). Therefore, among other things, it is true to say that the capability to assess the performance of HEIs most likely depends on their IC initiatives (Agostini et al., 2017; Singla et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Rebés et al., 2021). However, this endeavor is a bit compelling in an emerging economy, where it has existing tangible assets and generally ignores the intangible ones (Cheng et al., 2022; Garde Sanchez et al., 2021; Zapp, 2022; Maditinos et al., 2011). Few studies assert that IC spillovers positively influence the performance of HEIs in terms of scientific production and dissemination of knowledge (Vo & Tran, 2022; Nicolò et al., 2021; Bucheli et al., 2012; Cárdenas et al., 2013).

Therefore, to capture the recent trends for performance evaluation of HEIs, the given scale is more appropriately and sensibly developed. In light of this, we initially developed a preliminary instrument with a detailed list of HEIs’ performance indicators (i.e., research outputs, knowledge process capabilities, commercialization of knowledge, IPRs, entrepreneurial spirits, etc.) based on quality assurance, equitable access to education, academic collaboration, and linkages, after reviewing available literature and reports of HEC pertaining to HEIs’ performance evaluation standards such as “HEC: Knowledge Exchange Strategic Plan” (KESP-2012), “National Qualifications Framework of Pakistan-2015,” “Higher Education Medium Term Development Framework-II” (2011-15), and “Institutional Performance Evaluation Process-Manual for six standards.”

In the third step, a modified scale and a preliminary instrument developed in steps 1 and 2 were further refined by experts. In this sense, a panel of experts encompassing three academicians and two directors from quality enhancement cells was consulted to ensure the content and face validity of the instrument. They were requested to examine the instrument in all aspects, including the format, content, and wording. After an in-depth examination of the scale by experts, they recommended incorporating a few more items, for instance: “ratio of Ph.D. faculty” and “employee competency” in the context of human capital; “diverse academic programs,” “R&D programs,” and “procedures for IPRs” in the context of structural capital; “university employability” in the context of relational capital; “valuation of knowledge through commercialization,” “entrepreneurship spirits,” and “collaboration with academic and non-academic partners” were specifically included to measure the performance of HEI stringent with “medium-term development frameworks” (MTDFs-II) standards. In this way, this validation process led to further re-modification of the initial questionnaire. Hence, a final questionnaire was anchored after re-modification according to the feedback from experts, comprising 36 items related to IC elements (i.e., human, structural, and relational capital), a seven-item scale related to strategic innovation, an eight-item scale for process capabilities, and an eleven-item scale pertaining to the performance of HEIs. To capture the related effects, we used a five-point Likert scale covering (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) to cater for the better standardization and quantification of the scale (Lee & Choi, 2003).

In the fourth step, a procedure for pre-testing, sampling strategy, and data collection were defined. In this regard, we undertook the pilot study for purification purposes on a scale to establish the construct’s reliability and validity (Saunders et al., 2007). Keeping in view the prevailing effects of COVID-19, we developed the questionnaire on a Google Form and emailed it to 85 (teaching and non-teaching staff) working in various public and private sector HEIs in Pakistan. As a result, 39 of the 85 respondents provided their responses. Out of 39 respondents, 24 were faculty members, and the rest were administrative heads, thus representing a valid response rate of 45.88%. The criteria for the selection of participants were based on their level of experience and sufficient knowledge about IC initiatives within HEIs. Nevertheless, the results of the pre-testing revealed that both construct reliability and validity satisfactorily met the thresholds that led the study to proceed further for model testing using a cross-sectional research design.

In Pakistan, “tertiary education” refers to education beyond 12 years of schooling. This tier of education can better serve the labor market’s needs by providing a broader set of socio-economic benefits by formulating a skilled-based knowledge economy (Yoda & Kuwashima, 2020; Vo & Tran, 2022; Nicolò et al., 2021). Although Pakistan has introduced profound structural changes in the higher education system, it still faces enormous socio-economic challenges (OECD, 2020); such as low tertiary education attainment, a high level of income inequality, poor education and health standards, suboptimal scientific infrastructures, and the commercialization of innovative knowledge, among others, which have led to the impulse motivation that needs to be addressed if Pakistan, would like to immerse itself as one of the emerging knowledge-intensive economies in 2025 and realize its ambitious goals as illustrated in MDTFs-II. In addition, the purpose of the study was also shaped in view of its peripheral IC initiatives and sluggish implementation of growth policies in terms of strengthening strategic innovation and process capabilities in HEIs. As HEIs, they perform a phenomenal role in nurturing the national IC as a tool for socioeconomic development (Vo & Tran, 2022; Secundo et al., 2016). As a result of their critical role in the formation of a knowledge-based economy, Pakistan’s HEIs are an immersed area for research.

At present, to cater to the growing needs of labor markets, the “Higher Education Commission” (HEC) of Pakistan has set a clear vision for 2025 to strengthen the capacity building of their national IC through publicizing and restructuring the parameters of tertiary education in HEIs (Robertson et al., 2019; Kruss & Visser, 2017; Teixeira et al., 2018; McCarthy et al., 2018). Since its inception in 2002 (as the University Grants Commission Act of 1974), the HEC has made tremendous progress in institutionalizing systematic procedures by implementing various 5-year plans to reform Pakistan’s higher education system. These reforms are outlined as “medium-term development frameworks” (MTDFs-II), where IC initiatives in HEIs were considered an integral part of these reforms (HEC, 2016). In this sense, HEC has succeeded in achieving various structural improvements in the existing higher education system by ensuring different equality measures in terms of IC initiatives to map the relevance of the higher education system according to the growing needs of the labor market (HEC, 2021).

Although, after partition, Pakistan started its career only with one university in 1947 in the higher education sector. Now, Pakistan has 231 HEIs, including universities, research institutes, and degree-awarding institutes. Of these 231 HEIs, 141 are public-sector universities, and the rest are private-sector universities (HEC, 2016). A country with more than 210 million people currently has a gross student enrollment ratio of approximately 15%, which is far below that of other South Asian countries. It is envisioned to grow by 40% in the coming years (HEC, 2021) ).

Drawing from the above, we used the cross-sectional research typology to collect the data from respondents (i.e., teaching and non-teaching staff) serving in various HEIs in the provinces of Punjab, Sindh, and the Islamabad Capital Territory. Keeping this in mind, a sample must present an appropriate reflection of the population (Table 1). Presently, there are 231 HEIs in Pakistan, out of 170 HEIs (Punjab has 79; Sindh has 67, and Islamabad Capital Territory has 24) that cater to the growing needs of stakeholders in selected geographical regions. Nonetheless, we ignored the smaller HEIs, and thereby, consideration of the sample was made based on students’ gross enrollments in tertiary education, a higher number of qualified faculty members, and the number of graduates and patents produced, as we believed that this could better serve the intent of the study. Further, this enables us to condense the eligible sample to 105 HEIs out of 170. In the light of the conceived model (see Fig. 2), we assumed that HEIs’ capacity to transform the “knowledge inputs” (IC initiatives) into “knowledge outputs” (performance of HEIs) is channeled by their level of strategic innovation and process capabilities. Therefore, we only contacted the eligible respondents (minimum of three years of experience) based on purposive sampling. After selecting the eligible sample, we extracted the email addresses of respondents from the official websites of HEIs for the submission of online questionnaires during COVID-19 as a web link, with a cover letter to assure the confidentiality and privacy of respondents.

In this sense, to increase the response rate, follow-up emails as reminders were also sent to respondents at some intervals. Initially, we distributed 547 questionnaires, and finally, 258 usable responses were considered in the analysis, thus presenting a response rate of 47.16%. Professors completed 34 questionnaires, associate professors completed 47 questionnaires, assistant professors completed 64 questionnaires, lectures completed 73 questionnaires, registrars completed 18 questionnaires, and the remainders were completed by office bearers (i.e., the office for research, innovation, and commercialization (ORIC); the controller of examinations; and the treasurers). In the fifth step, we examined the non-response and common method biases. Non-response bias is a critical situation that normally occurs when respondents statistically differ from non-respondents in surveys (Saunders et al., 2007; Chikazhe et al., 2021; Isa, et al., 2008). To assess respondents’ ability to represent themselves, we used an independent samples t-test to compare the mean scores of early and late respondents (Armstrong & Overton, 1977). As illustrated in Table 2, this indicates that the comparison of early and late respondents failed to disclose any statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). Thus, non-response bias was not considered a critical problem in this data set, and therefore, respondents appeared to reflect an appropriate sample in the data set.

After successfully examining the non-response bias, we also observed the threat of common-method variance by employing the Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Several studies have alluded to the fact that common-method variance can be a serious problem while conducting research in an organizational context (Roxas et al., 2014). It creates systematic biases in the data and thereby harms the scale’s validity by expanding or reducing the results of correlations. Harman’s single-factor test is the most robustly used technique to address any potential threat of common method variance in the scale. In this sense, we employed exploratory factor analysis (EFA) without iteration to identify the variance explained by all the items of a single factor. Thus, results (Table 3) indicate that no single factor explained the variance of more than 50% (see table), and hence, we contended that common-method bias is unlikely to be a serious concern in our study (Roxas et al., 2014; Lages & Piercy, 2012).

Results and Analysis

Descriptive Analysis

Table 4 shows the mean, standard deviation, and pairwise correlation among the variables. Correlations between variables showed that human capital is positively related to mediators: strategic innovation (r = .778, p < .01), process capabilities (r = .646, p < .01), and the outcome variable of HEIs’ performance (r = .729, p < .01). Similarly, structural capital and relational capital are found to be positively correlated to mediators (i.e., strategic innovation and process capabilities) and the outcome variable (performance of HEIs).

Reliability Analysis

Reliability tests the inconsistency of items within the scale. Cronbach’s alpha values were calculated to test the reliability, and the results showed (Table 4) that all the constructs are internally consistent as Cronbach’s alpha values of all constructs are greater than the threshold value of 0.70 (Cronbach, 1951; Pallant, 2010).

Validity Analysis

Next, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to assess the reliability and validity of the scale. For validity, various model fit indices were checked to assess the model goodness of fit. Table 4 demonstrates that all desired fit indices are satisfactorily meeting the threshold values, thereby indicating a good model fit. Furthermore, the CFA aided in determining convergent and discriminant validity. The convergent validity was calculated by employing the average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and factor loading values. As per the criteria, the AVE, CR, and factor loadings should be greater or equal to 0.5, 0.7, and 0.5, respectively (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2014). The results are shown in Table 5, indicating that all the constructs fall within their threshold values.

In last for discriminant validity: Cronbach’s alpha of a construct is compared to its correlations with other model variables (Sila & Ebrahimpour, 2005). If the alpha value is sufficiently larger than the average of its correlations with other variables, it indicates the presence of discriminant validity (Ghiselli, et al., 1981). Table 5 indicates that the difference between the alpha value of each construct and the average correlation of each construct with the other constructs was adequately large, i.e., human capital = 0.220, structural capital = 0.203, relational capital = 0.174, strategic innovation = 0.118, process capabilities = 0.218, and performance of HEIs = 0.244. According to Sila and Ebrahimpour (2005), all these values provided evidence of discriminant validity.

Mediation Analysis

The proposed direct and indirect effects were analyzed by using a process macrodeveloped by Hayes for bootstrapping samples with 95% confidence intervals. Following Hayes (2018), firstly, the direct effect of IC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” (i.e., human, structural, and relational capital) on “knowledge outputs” (performance of HEIs) was checked. Second, the indirect influence of IC initiatives (human capital, structural capital, and relational capital) on the performance of HEIs was analyzed in the presence of mediators (strategic innovation and process capabilities), and later on, the effects of mediating variables (strategic innovation and process capabilities) on dependent variables (performance of HEIs) were explored.

Direct Effect

Table 6 reveals the results of direct, indirect, and total effects. In terms of direct effects, it appears that human capital has a positive and significant influence on HEI performance (β = 0.387, at p < 0.05), supporting the hypothesis (H1). Furthermore, the direct effects of structural and relational capital positively (β = 0.250; β= 0.217) lead to the performance of HEIs at p < 0.05, supporting hypotheses H2 and H3. Furthermore, the direct impact of human capital on strategic innovation and process capabilities was positive (β = 0.652; β = 0.853) and significant (p < 0.05), supporting hypotheses H5 and H12. Similarly, the positive and significant impact of structural and relational factors has been observed on the strategic innovation and process capabilities of HEIs, thereby substantiating hypotheses H7, H14, H9, and H16. Continuing in the same direction, the direct effects of mediating variables, i.e., strategic innovation and process capabilities, on the performance of HEIs (β = 0.262, p < 0.05; β = 0.292, p < 0.05) are also found to be positive and significant, thereby supporting the hypotheses H4 and H11.

Indirect Effects

Table 6 highlights the results of parallel mediation analysis by using process macro to test the indirect effects of strategic innovation and process capabilities. Hayes (2018) explained that if the direct effects of dependent and independent variables are significant, then, by applying meditators, the indirect effect remains significant. This implies the existence of partial mediation. Whereas, if the direct effect is insignificant and the indirect effect becomes significant, it indicates the presence of full mediation in the proposed mediation model. However, the non-zero values of the confidence interval (CI) are an indication of significant influence.

The results from Table 6 indicate that strategic innovation partially mediates, as the direct effects of human, structural, and relational capital on the performance of HEIs and indirect effects on the performance of HEIs through strategic innovation as a mediator are significant with the following: β = 0.223, CI: 0.100–0.443; β = 0.247, CI: 0.098–0.492; and β = 0.293, CI: 0.051–0.449 respectively. Similarly, in the case of process capabilities as a mediator, it was also found that process capabilities partially mediate the relationship between all three important strands of IC (human, structural, and relational) and the performance of HEIs with the following: β = 0.189, CI: 0.033–0.438; β = 0.178, CI: 0.020–0.420; and β = 0.156, CI: 0.020–0.395 respectively. This indicates that both the residual direct effects and specific indirect effects are significant with non-zero confidence intervals. The results of the structural model are displayed in Fig. 3.

Discussion

In this paper, we aim to establish the link between “knowledge inputs” → “processors” → “knowledge outputs” (I →P →O) model, using the theoretical lens of KBV (Guerrero et al., 2021; Paoloni et al., 2021; Cricelli et al., 2018; Pedro et al., 2019; Mills & Smith, 2011; Delgado-Verde et al., 2011; Elena, 2004; Cai and Liu, 2015). Our results of the study revealed that IC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” significantly influence the “knowledge outputs” (performance of HEIs) by capitalizing on the role of “processors” (strategic innovation and process capabilities) as mediators (Cheng & Chang, 2022; Dezi et al., 2019; Arun & Shekhar, 2020; Thrassou et al., 2020). These findings of the study are consistent with theoretical prisms of the “dynamic IC transformation process” (Guerrero et al., 2021; Paoloni et al., 2021; Teixeira et al., 2018; Singla et al., 2022; Salinas-Avila et al., 2020), which indicates that IC initiatives are paramount to augmenting the performance of HEIs in terms of leveraging greater “knowledge outputs” (Hayaeian et al., 2021; Matricano et al., 2020; Guerrero et al., 2021; Robertson et al., 2019; Elena, 2004; Ramírez et al., 2007). Nonetheless, the results of the study demonstrated some additional noteworthy empirical support, particularly in the case of a developing nation.

While testing the direct effects (H1, H2, and H3), this study revealed that the contribution of HC initiatives in measuring the performance of HEIs (knowledge outputs) is more detrimental than that of SC and RC and thereby offered a unique contribution within the context of HEIs in Pakistan. These findings are corroborated by the main theoretical perspectives that analyze the relationships between the “knowledge inputs” and “knowledge outputs” using the dynamic IC transformation process (Guerrero et al., 2021; Salinas-Avila et al., 2020; Paoloni et al., 2021; Aversano et al., 2020; Bucheli et al., 2012; Cricelli et al., 2018).

With respect to the direct and indirect roles of strategic innovation (H1, H5, and H6) between HC initiatives and the performance of HEIs, results of the study illustrated partial mediation, which indicates that HEIs are profoundly involved in HC initiatives as “knowledge inputs” to improve the innovative capability of teaching and non-teaching staff (Guerrero et al., 2021; O’Neill and Bagchi-Sen, 2020; Robertson et al., 2019; Cricelli et al., 2018; Secundo et al., 2016). A plausible explanation for this relationship is that HC initiatives are crucial enablers to foster the strategic innovation process in HEIs to do things innovatively, improving their problem-solving skills and creativity when they exchange knowledge in academic meetings (Beltramino et al., 2020; Yoda & Kuwashima, 2020; Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005; Delgado-Verde et al., 2011). Consistently, while explaining the most predictive role of HC initiatives on strategic innovation (H5; β = 0.853), the study also highlighted the HC initiatives as the most valuable “knowledge inputs” to nurture the strategic process. Such initiatives aim to improve the performance of HEIs as “knowledge outputs” by reinforcing research outputs, valuing knowledge through commercialization, increasing the number of graduates, and producing IPRs (Andreeva et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021; Pedro et al., 2019; Secundo et al., 2015; Larrán et al., 2010; Ramírez and Gordillo, 2014). Thus, these findings confirm the existence of the proposed “dynamic IC transformation process” consistent with earlier studies (Guerrero et al., 2021; Nicolo` et al., 2021; Petruzzelli et al., 2018; Huang and Huang, 2020; Cricelli et al., 2018).

Our results also support our argument about mediating the role of process capabilities between HC initiatives and the performance of HEIs in the dynamic IC transformation process. Both directly and indirectly (H11, H12, and H13), the results of the study recommended that process capabilities partially mediate the relationship between HC initiatives and the performance of HEIs. This indicates that a greater inclination toward HC initiatives turns toward aligning the internal and external process capabilities of HEIs to achieve the desired performance objectives (Cheng et al., 2022; Silvestri & Veltri, 2011, Sharabati et al., 2010). These findings provide unique insights consistent with the theoretical underpinnings of “knowledge inputs” → “processors” → “knowledge outputs” model by evidencing that process capabilities encourage the performance of HEIs by fostering the knowledge process capabilities, greater collaboration, and employability of students (Paoloni et al., 2021; Guerrero et al., 2021; Maritz, 2010; Link & Ruhm, 2011; Ramírez et al., 2007; Elena, 2004).