Abstract

In this article, we explore how an important state intervention in cooperation with many civil society actors led to impact investing field emergence, intending to create favourable conditions for social entrepreneurship and social innovation. Twenty in-depth interviews were conducted in Portugal, with the main players in the field, including private sector, government, NGOs, and EU authorities. The ecosystem formed by these actors is analysed under the institutional theory lens and through an inductive method, leading to a process-based model. The results of our case study show a state struggling to involve private sector in providing resources to the field. On demand side, new entrepreneurs are finding difficulties in meeting legal requirements and answering suppliers’ selection criteria. Intermediaries contribute to reducing complexities, but are fighting to encounter their place in the field. Our evidences further suggest that social entrepreneurship and social innovation could be implemented as socially embedded actions, in response to local demands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

State intervention to create the necessary conditions to boost social entrepreneurship and innovation has received a lot of attention in recent years (Bozhikin, Macke, Costa, 2019). One of these initiatives is the incentive to build the field of impact investing. The impact investing field integrates investors who make financial investments in early-stage organizations with the goal of receiving financial returns and creating measurable social impact (Agrawal & Hockerts, 2021; Mangram, 2018).

Among others, national governments, local government agencies, non-profit organizations, and foundations are all at play in the emerging field of impact investing (Tekula & Shah, 2016). Governments often play an enabling role, creating market preconditions such as infrastructure development and productivity stimulation (Tekula & Andersen, 2019). Governments can also play other roles, such as regulators, policy makers, and investors, financing and nurturing supply, boosting capital flows, and regulating demand (Martin, 2015).

Researchers reveal the importance of cross-sector collaborations with the public sector (Michelucci, 2017) as well as with for-profit businesses as a source of social innovation (Huybrechts et al., 2017; Tekula & Shah, 2016). However, reasons, processes, and timing leading to collaboration in social entrepreneurship ecosystems are still “an emerging area of research with the potential to advance theory and inform practice” (De Bruin et al., 2017, 576).

When a lens is placed on ecosystem actors and their relationships, we identify a restricted interplay and the need for more collaboration to improve the funding and financing of social entrepreneurship (Lehner & Nicholls 2014) as well as for them to take advantage at different stages of the innovation process (Geobey et al. 2012).

Furthermore, the absence of a unified market with coherent guidelines contributes to a lack of confidence and liquidity, leading many impact investors to adopt a conventional investment approach when selecting and evaluating investments (Bengo et al., 2021). As a result, scalability, profitability, and a highly qualified management team are among the criteria used by investors, when considering entrepreneurial initiatives individually (Block et al., 2021).

Therefore, coordination is identified as a requirement for the proper functioning of the relationship between impact investing and social entrepreneurship ecosystems. Coordination means that participants engage in interdependent efforts, linked to one another, giving structure to the system and making it function as a connected group rather than a collection of autonomous individuals (Roundy, 2019).

Two schools of thought underlie the differences in these two ways of defining impact investing. The individualist is supported by the utilitarian approach, which identifies social innovation by the consequences of the social impact of innovation rather than the processes of innovation. On the other hand, the process-based literature identifies social innovation more by its continuous flows of interactions and events. This study reinforces the latter, defining markets as shaped through a non-linear network process of social and technical interactions, as well as the construction of social innovation, focusing more on the processes of innovation than on its consequences (Mollinger- Sahba et al., 2020).

This approach focuses on the collective rather than individual projects and has the Social Innovation Europe as one of the most prominent examples (Zivkovic, 2017). In 2012, the Social Innovation Europe Report Initiative recommended that the European Union supports all innovation systems rather than individual projects and emphasized that policy makers are vital to creating conditions for systemic change (Davies et al., 2012). This collective impact approach emphasized linking mutual activities, as the conditions for cross-sectoral collaborations are facilitators of collective positive impacts in the social economic ecosystem.

Following the Social Innovation Europe Report, in 2015, by the Resolution of the Council of Ministers (n° 73-A/2014, 16th December), the Portuguese government created a new agency called Portugal Social Innovation (Portugal Inovação Social – EMPIS) and assigned to it the mission of developing the social investment market until 2020. This agency, endowed with €150 million from the European Social Fund, was attributed the mission of supporting growth on the supply and demand side of the social investment market for underdeveloped regions in Portugal, targeting the lack of adequate funding for social innovation and entrepreneurship through the provision of investment capital, venture philanthropic capital, and outcomes-based funding (OECD, 2017). This initiative connected a huge network of actors (Mendes & Pinto, 2018), from different areas contributing to the emergence of the field of impact investing in Portugal.

In the world, the concept of impact investing was first mentioned in a conference at Belaggio Center in 2007 to describe investments made with the intention of generating financial return and socioenvironmental impacts (Rodin & Brandenburg, 2014). Since then, international agencies, governments, private companies, and the third sector, from different countries, have shown concern, analysed its potential, and made recommendations and alliances to construct the new field (Clarkin & Cangioni, 2016). The European Union (EU) has been a champion on that, acting through the European Social Innovation and Impact Fund. Indeed, EU has enabled investments in social enterprises while supporting the ramp-up of social innovation—understood as “innovative solutions and new forms of organization and interactions to tackle social issues” (BEPA 2011, 341).

The experience of EU investment in Portugal was selected as our case study because it is emblematic, an example of a highly intricate network of actors that are joining forces to build a sector, with the important contribution of a specific public policy to catalyse social entrepreneurship and social innovation to its underdeveloped regions, the north, center, and Alentejo regions, which have a per capita GDP lower than 75% of the European average. It involves not only philanthropic and private sector, but also is strongly supported by the state, and funded by the European Union (OECD/European Union, 2017). It is also a case that reveals difficulties and challenges in the process of implementing impact investing as a policy (Maduro et al., 2018).

This empirical study will support the answers for our main research question: Which dynamics and mechanisms can contribute for the emergence process of impact investing field, fostering social entrepreneurship and social innovation in a socially embedded approach?

Our study aims to contributing to better understanding of strategies, processes, and networks leading to the emergence of impact investing field and social entrepreneurship, while supporting rump-up of social innovation as a process. It also enriches the understanding of how a relationship between foreign, national, and regional actors can lead a state to foster a field construction from the scratch. As a theoretical contribution, this paper shows the usefulness of an institutional approach to analyse changes in the impact investing field, reinforcing the stream of literature of social innovation built as a process. .

Most of the relevant material for this study was collected through twenty in-depth interviews, conducted in October–December 2018 in Portugal with members of the ministry cabinet, former ministry member, civil servants of state agencies, directors of NGOs, banks and foundations, project coordinators, ministry advisors, and consultants.

This article is organized as follow: a brief history of impact investing industry is presented in the next section. Section "Theoretical Perspectives for Analysing the Emergence of Impact Funds Field and Social Enterpreneurship" describes theoretical perspectives for analysing the field. Section "Methodological Approach" explains the methodological approach. Section "Findings" lays out results, presenting a process-based model integrating relevant mechanisms and forces for to the field emergence, and Section 6 presents discussion. Finally, Section "Discussion" brings final considerations.

Impact Investing Field: Built on the Rhetoric of the State’s Lack of Financial Capacity

Impact investing refers to the use of investment capital to help solve social or environmental problems around the world with the expectation of financial returns (Quinn & Munir, 2017). It combines a variety of debt and equity instruments, and sometimes grants (Martin, 2015).

The first experiences of impact investments can be traced back to the nineties, when foundations’ initiatives blended institutional orders from philanthropic and market fields. Calvert Foundation, created in 1995, and the Acumen Fund, founded in 2001, were both based on the idea that markets alone were not able to solve social problems (Pirson, 2012).

Over the years, new alternatives emerged to finance socioenvironmental projects (Daggers & Nicholls, 2016), based on the assumptions that the state was unable to sufficiently invest in social projects and that this demand could be supplied by the private sector capacity. One example of impact investing mechanism is SIBFootnote 1 (social impact bond), which emerged in 2010 as an alternative to finance public projects with private resources, operationalized through partnerships with third sector (Broccardo et al., 2020).

Three years later, reinforcing the rhetoric of the state’s lack of capacity in handling 2008 economic crisis, the Task Force for Social Finance World (G8 Social Investment Forum – plus Australia, without Russia) presented recommendations regarding asset allocation, social impact measurement, and lock-in for social mission, involving the private sector. Additionally, impact investing has become a key issue in public policy recommendations from other multilateral organizations (OECD, 2019).

In the academic sphere, scholars have pursued the theme since 2005, under different approaches (Agrawal & Hockerts, 2021). Most of them follow the mainstream avenue, identifying impact investing as a way to fill the blanks left by the state. For example, McWade (2012) analyses the role of private capital for the entrepreneurship development, and Dowling (2017) emphasizes the relevance of attracting funds from private to public sector as a strategy for asset allocation, intentionally funding initiatives that combine a measurable social and environmental impact with economic sustainability.

Moreover, definitions have become more specific or quantifiable (Agrawal & Hockerts, 2021), including discussions about lack of risk/return metrics (Brandstetter & Lehner, 2015) and balance between profit and social impact (Höchstädter & Scheck, 2015).

Recently, in a different avenue, some authors have been arguing in favour of a more socially embedded approach of impact investing as a social innovation booster, identifying it more as a process than as a consequence of investors’ initiatives (Mollinger-Sahba et al., 2020). Lall (2019) argues for the need of measurement in social enterprise and social finance change over the course of its relationship. Quinn and Munir (2017) discuss how social actors navigate and maintain social and political arrangements. Then and Schmidt (2020) advocate for a field that is born from the demands of society and not from definitions of priorities from the perspective of suppliers.

Theoretical Perspectives for Analysing the Emergence of Impact Funds Field and Social Entrepreneurship

To take impact investing into account and its relation to social entrepreneurship in the level of organizational field as a process, we draw on Fligstein and McAdam’s concept of “strategic action field (SAF)”, a stream of institutional theory. From institutional theory perspective, inter-organizational relationships provide inputs for new field-level institutional arrangements (Huybrechts et al., 2017). Fligstein and McAdam (2012) build on that, emphasizing the role of skilled actors, as well as the state in framing disputes and coalitions for field building, stabilization, and crisis.

In SAFs, central events may generate a kind of punctual equilibrium. However, many sources of change can emerge endogenous, when actors dispute positions and create new identities to fortify the movement of the field, and exogenous, when the terms of the competition are altered by forces and actors out of the field. State is also a source of change, that is “simultaneously shaped by dynamics ‘internal’ to the field and by events in a host of ‘external’ strategic action fields” (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, 57).

Impact investing field may be structured as a market (Nicholls & Emerson, 2015; Mulgan, 2015, Rexhepi, 2016), composed by suppliers, intermediaries, and demand side (Phillips & Johnson, 2021), but is also a social innovation that can be built as a market initiative embedded in the society (Mollinger-Sahba et al., 2020). In those three spheres, challengers and incumbents cooperate or compete for resources trying to maintain their positions. In that, social skilled actors, able to convince others and manage the history course, can champion the use of organizational resources and innovative actions, promoting consensus and legitimating actions (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012).

On the supply side of impact investing world market, there is a large volume of resources, currently US$1.1 trillion (GIIN, 2021) and investors looking for mixed returns in the allocation of their capital (Barber et al., 2021). Suppliers include individuals, institutions (e.g. foundations and banks), and governments (e.g. agencies promoting and financing impact and sustainable investments). They vary in size and mission (Alijani & Karyotis, 2019), and for different reasons, all these organizations compete for high-quality projects with track record (Brandstetter & Lehner, 2015).

Demand side includes social enterprises, philanthropic organizations (such as NGOs), or cooperatives. They compete for capital from investors. To attract these investors, demand side actors (the investees) need to present a compelling case on the potential social impact and financial return of their projects (Phillips & Johnson, 2021). They face many difficulties to positioning in the field: lack of understanding on suitable types of investments for achieving their strategic objectives (Nicholls & Emerson, 2015), accessibility to talent and expertise, high level of fragmentation (Martin, 2015), and unsustainable businesses models with market revenues falling short of expenditures (Dohrmann et al., 2015).

Intermediaries make connections between investors and investees. The main role is to gather capital from different sources, such as charities, microfinance banks, or private investors, aligning capital and projects. Intermediaries may also have other roles, such as information providers and providers of assessment and metrics (e.g. the Global Impact Investing Network, GIIN) (Phillips & Johnson, 2021) or access to people, networks, and expertise (Nicholls & Emerson, 2015). The most evident gap intermediaries suffer is on data consolidation/data creation and performance evaluation activities (Nicholls & Emerson, 2015), resources for which they compete.

Actors interact on the basis of social norms and shared cognitive elements, enabling mutual recognition, and legitimization of actions. As they interact, they create “the rules of the game” and the state has the formal authority to intervene in, set rules for, and generally pronounce on the legitimacy and viability of most non-state fields” (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, 19), sometimes, through creation of internal governance units—department, ombudsmen, and agencies that arise and transform.

Indeed, governments incentivize the impact investing field to grow by interacting with private and third sector to provide infrastructure and services (Brown & Norman, 2011; Bugg-Levine et al., 2012), strengthening supply or demand side (Then & Schmidt, 2020) and changing dynamic nature of institution formation (Ramesh, 2020).

Methodological Approach

In order to provide transparency about our methodology, and enabling replicability of our research, below we detailed aspects of the qualitative research process and research design (kind of qualitative method, sampling procedures, roles of participants), instruments and procedures of data collection, interviews’ procedures, saturation point, data analysis (explaining our data coding procedures, first-order codes creation, and procedures to connect them, creating second- and higher-order codes) and empirical setting (Aguinis & Solarino, 2019)

To answer our research question, we studied the case of Portuguese impact investing field—a pilot project sponsored by the European Commission to amplify the practice around Europe (Maduro et al., 2018). We developed a qualitative case design (Pettigrew, 1990) based on our primary goal of analysing how the emergence of impact investing field fosters social entrepreneurship and social innovation in a process based model. Our methodological design was strongly influenced by the work of Stake (1994), for whom a case study is instrumental when it explores a research question that is not limited to the case itself, but allows for some degree of generalization.

Data Collection and Analysis

The main sources of data collection were transcriptions from twenty interviews, conducted in October–December 2018 with elite informantsFootnote 2 (Table 1), from ministries, government agencies, private banks, nascent impact investing funds, NGOs, social entrepreneurships CEOs, consulting companies, and academics who had relevant roles in the emergence of Social Innovation Pilot Project in Portugal. We applied a gradual selection principle of sampling relevant units (interviewees) to answer our research question, appropriate when the research goal is the generation of broadly defined themes (Teddlie & Yu, 2007). Although we previously selected and contacted elite-informants, through personal and professional network, LinkedIn or email, it was necessary also to rely our sampling on referrals from initial subjects to contact additional informants. Therefore, a snowball technique was used, suitable for samples of difficult access (Vogt, 1999).

We stopped the interviews when we reached our theoretical saturation point; when after an interactive process of sampling, collection, and simultaneous analysis of data, we realized that we had obtained patterns that made sense to better understand the mechanisms and dynamics that encourage or hinder social entrepreneurship and innovation in the field and their interactions (Hennink et al. 2017).

The period of collected data refers to two different Portuguese governments—one applying the memorandum of understanding signed with IMF (International Monetary Fund), EU, and ECB (European Central Bank) to avoid Portuguese bankruptcy (from 2011 to 2015) and the other after the “troika” (MF, EU, and ECB) intervention—with different political approaches (after 2015).

Each interview followed a semi-structure questionnaire, divided in three blocks: (1) how they were used to identify themselves and others in the field; (2) how was their relationship, investors/investees/intermediaries; and (3) how they used to see the state and vice-versa. Usually, they talked about interactions and interdependences between them and the many challenges and triggers. As we advanced in the number of interviews, we started to confirm relationships between the constructs we were founding. The interviews were recorded, following interviewees’ approval, and then transcribed. All organizations and individuals’ identification were not provided, in order to preserve anonymity. Secondary data were collected from public legal references and reports provided by decision makers, public institutions, non-profit organizations, and other interviewees. Most information deals with agreements between the EU and the Portuguese State (e.g. regulation amending Regulation (EU) No. 345/2013), on the creation of EMPIS – Portugal Inovação Social Mission Structure (Resolution of the Council of Ministers 73, 2014), or comes from public databases (e.g. Banco de Portugal; Social Equity Initiative).

Our analysis is aligned with process-based logic (Langley, 1999). The interview answers analysis was based on an open, axial, and selective coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). At this first stage, we followed few theoretical concepts to guide the analyses of informants’ voices, identifying constructs and relationships between them (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The most prominent concepts identified at this stage were related to social entrepreneurship and impact investing, such as frames, legitimation criteria, mobilization of actors, and state facilitation. Then, we looked for connections between concepts seeking for circumstances that originated them. In parallel, we analysed and coded data, asking interviewees about our coding in order to validate it. At this point, we were switching between literature and the emergent concepts, to identify new relationships between them (Gioia et al., 2012). Data structure emerged from this process (Fig. 1), indicating (a) the first-order concepts, emerged from the in vivo data analysis; (b) the second-order themes related to theory of fields; and (c) aggregate categories—consensus dynamics, formation dynamics, and state facilitation obtained by moving back and forth to the literature and resulting identification of new relationships between concepts.

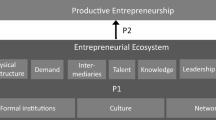

Figure 2 shows the aggregate categories and the second-order themes forming a process-based model of impact funds field dynamics. The model represents the relationships between the three broad categories and their constitutive themes. Reciprocal relationships were derived by identifying how respondents make connections between constructs. For example, how do they discuss the mobilization of actors simultaneously with the construction of frames (e.g. how to mobilize to leverage the existing impact investing frame as a mechanism to foster social entrepreneurship, filling a gap in the market). The propositions resulting from this phase are presented in the “Discussion” section of this article.

Empirical Setting: Institutional Background

Our research context is the impact investing industry in Portugal. The industry has stood out in Europe as a way to contribute to directing resources towards the solution of economic and social problems. After the financial crisis that started in 2008, impact investing was identified as a way to include socioenvironmental return as one of the investment possibilities in the capital market, traditionally based on risk and financial return.

In the 2000s, the field grew on two fronts: in social enterprises and in financial services. Social enterprises accounted for about 6.5% of jobs in Europe in 2010 and proved to be resilient to economic and financial crises, with potential for social and technological innovation, creation of inclusive, local and sustainable employment (Maduro, 2018). New laws were created to strengthen social entrepreneurship in Europe and develop the market. The Single Market Act launched the “Social Business Initiative”, creating an enabling climate for social enterprises in 2011 (COM (2011) 0682, 2011). It was followed by EU Parliament resolutions of 2012 and 2015, which recognized the relevance of social issues and solidarity economy.

On the financial front, there was a sharp growth of 50% of the European impact investing market between 2011 and 2013, then with 30 billion euros, but still a small share of the capital market in Europe. To stimulate this market, the EuSEF legislation was created, encouraging investment funds aimed primarily at generating social impact. In 2017, the European Parliament proposed amendments, reducing the minimum investment in EuSEF from €100,000 to €50,000, removing the barrier to entry for small investors (Regulation (EU) 2017/1991, 2017). At the basis of all these initiatives was the approval, by the EU Parliament, in 2014, of 70 billion euros for the European Social Fund (ESF), one of the five European structural and investment funds, financing priority projects in the field of education, job creation, social inclusion, and training (Regulation EU No 346, 2013).

This information outlines the empirical context of this study in terms of Europe. However, our research is also shaped by local space.

Although matured first in countries such as the UK, in 2011, Portugal already presented conditions and interests that made the country a suitable terrain for the industry. Its implementation constituted an opportunity for the application and contribution of the European Social Fund (ESF) to overcoming social crises, driven by the austerity measures of the 3-year economic adjustment program agreed by Portugal with the EU, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund in 2011 (Maduro, 2018).

In addition, the country had unique favourable conditions, such as a strong and traditional social economy supported by the local government, capable of stimulating social entrepreneurship and innovation. The maturity of the Portuguese State to work with the high number of entities with potential for social impact at local and regional level contributed to create the bases for the growth of a robust market in many underdeveloped regions of the country.

To follow our theoretical framework and better answer our research question, we describe below the Portuguese impact investing field as a market that encompasses the supply side, the demand side, and the intermediaries, based mainly on information from interviews, but also on documentation provided by the interviewees.

Supply Side

In Portugal, supply side is represented by actors providing financial resources such as impact funds, banks, business angels, family offices, and, in specific cases, the state providing financial resources received from the European Union.

The state

Portugal impact investing industry has gained momentum since 2014, when Portuguese government created a special agency called “Portugal Inovação Social (EMPIS) (OECD/EU, 2017)”. This agency creation was an important achievement of many actors’ efforts such as academic experts, opinion leaders, politicians, foundations, and other civil society groups who were already working to improve entrepreneurship in Portugal since 2011. With and endowment of 150 million Euros, EMPIS was created with the aim of designing and developing a policy framework as well as to support the negotiation process with the European Commission (EC) to define the investment priorities of ESIFootnote 3 - European Structural and Investment funds, from 2014 to 2020. In order to achieve its objectives (funding the full life cycle of social innovation and social entrepreneurship projects, mobilizing the social innovation ecosystem, and stimulating the formation of a social investment market in the country), EMPIS created four different instruments (Maduro et al., 2018).

The first instrument (capacity building) aimed at enhancing capacity building and management skills of social economy entities, preparing them to generate social impact and capture social investment. The second (partnerships for impact) had the objective of stimulating philanthropic organizations to provide resources to social innovation and social entrepreneurship initiatives (SISEI). The third (social impact bonds (SIB)) had the objective of tackling societal issues through innovative solutions, bringing private investments to invest in social innovation initiatives. The fourth had the objective to provide governmental resources to social entrepreneurships by the establishment of an investment fund (SIF). SIF is a wholesale fund that co-invests, through financial intermediaries in (SISEI) in the process of its consolidation or expansion, through debt and equity.

Having invested in 527 projects until December, 2021 (Portugal Inovação Social, 2021), EMPIS initiative is the centre of impact investing field in the country, and it was mentioned by many interviewees as the key actor, and we will show in the next step of this section.

Foundations

These are very relevant actors on the supply side ecosystem. At the core there is the biggest Portuguese foundation (Foundation 1), the 35th world largest in philanthropy, focused also on promotion of arts, science, and education, providing social innovation solutions. There are also other foundations associated with large listed companies that have participation in social entrepreneurship, setting in different economic sectors.

The Traditional Financial System

The public policy was designed to attract the traditional financial system, particularly the banking sector. However, instruments created on the 1st phase of EMPIS (from 2014 to 2018) did not attract these players. Only a traditional mutualist financial institution and a small bank sited in Portugal invested in the field. The first created an executive office, specifically to handle social business and social impact and has co-investing in social entrepreneurship projects since then. The other, a small foreigner private bank, had already some tradition in philanthropy in Africa and Europe and recently took part of a new impact fund in Portugal. .

Impact Investing Funds

Until 2018, Portugal had only one running impact investing fund, the Fundo do Bem Comum, a venture capital company created in 2011 by ACEGE (Association of Catholic Managers) and private shareholders, during a huge socioeconomic crises, aimed at providing funds for unemployed people over forties, who were potential entrepreneurs. Nowadays, there are others with a more ambitious proposition value and financial return expectations. One example is Impact Fund 1, with 40 million euros, with shareholder participation of public banks and other small private shareholders, attracting social entrepreneurs from abroad to invest in early-stage social enterprises, promising financial return close to traditional venture capital companies.

Venture Capital Companies

There are several venture capital companies in Portugal, and their representative structure is APCRI – Associação Portuguesa de Capital de Risco e Desenvolvimento. A venture capital company created in June 2012, during the Portuguese socioeconomic crises, by the merger of 3 state-owned venture capital companies is particularly important. It invests in seed rounds of Portuguese start-ups in tech, life sciences, and tourism. Its shareholders are public (75%) and private companies (25%).

Other Private Investors

There are several small investors, related to traditional families and some corporations (as part of their social responsibility initiatives). Some consulting companies, for example, have invested in impact businesses. They are creating internal funds to organize its partners’ donations as well as the selection of areas to receive investments (such as training, entrepreneurship, and employability).

Intermediaries

Intermediaries are all involved in the connexion between supply and demand sides.

Service Providers

There are NGOs born from citizens and the academic universe, working on social issues in Portugal. They make partnership with foundations and private sectors to implement social projects such as solutions to develop personal and professional competencies of unemployed youth or elderly services, for example.

Legal Offices

The current legal framework adopted in the country seems inadequate to answer impact investing needs, mainly due to the absence of a legal social enterprise definition (Ferreira et al., 2021). One of the financial instruments created by EMPIS (SIF Equity), for example, assumes that private investors could invest in equity in social innovation and social entrepreneurship initiatives (SISEI). However, most of these SISEI are developed by IPSS (private institutions of social solidarity), non-profit organizations that do not have booked social capital, thereby making impossible the selling of part of its capital as equity.

Business Angels

APBA (Portuguese Association of Business Angels) is a non-profit organization with 150 members. Regarding social impact business, the association works as intermediary between business angels and entrepreneurs interested in resources to start or improve their business. APBA participates in committees to select the best projects to receive investments from association members.

University Partners

One of the most relevant academic influencers was the French INSEAD (Institut Européen d'Administration des Affaires), which started its participation in Portuguese social entrepreneurship environment in 2008, with a partnership between Cascais municipality and INSEAD created the IES – Social Business School. This initiative has been progressively fleshed out, spreading the idea around other universities in Portugal, such as University of Lisbon and Universidade Católica.

Other Government Agencies

Other government agencies are relevant, namely, those associated with investment support to small and medium enterprises and their capacity building. Of particular relevance is Agency 1, the main agency in the Portuguese entrepreneurship environment. Its mission is to stimulate funding to small and medium companies, by managing special investment funds. For example, concerning SIF debt, if a private bank decides to lend resources to a SISEI (social innovation and social entrepreneurship initiative), Agency 1 makes credit analysis and intermediation with EMPIS.

Demand Side

Social Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship Initiatives

Some business models are still struggling to find ways to promote social inclusion in a sustainable basis. Social entrepreneurship initiatives, offering training in technology or the opportunity for unemployed youth learn computational languages, for example, do not generate revenues, following the called “one-side social mission model”, aimed at a social target group which “does not have the financial means to pay for the provided good or service” (Dohrmann et al., 2015, 136). In the last case, after finishing the course and finding a job, participants pay loans back at below-market rates.

Solidarity Economy NGOs

Some NGOs are positioned on the demand side, requiring resources from the government to achieve its objectives. They belong to a specific group of actors of NGOs working in the solidarity economy, challenging the dominant vision. They sustain that not all social problems should be treated as social business, considering difficulties of impact assessment and funding.

On the next topic, we will present and explain each first-order concept, as shown in Fig. 1. Letters beside the first-order concepts indicate if they were mentioned by members from supply, demand side, intermediaries, or state. First-order concepts are illustrated with interviewees’ quotes. We provide information only about their positions (in brackets), in order to preserve anonymity.

Findings

With the aim of responding our research question, “Which dynamics and mechanisms can contribute for the emergence process of impact investing field, fostering social entrepreneurship and social innovation in a socially embedded approach?”, we worked on our findings, identifying levers and challenges to be overcome in order that the field of impact investing achieves legitimacy as a promoter of social entrepreneurship and social innovation.

The Absence of Consensus Hinders the Growth of the Field and the Promotion of Entrepreneurship

Our findings revealed that impact investing is seen as a good way to solve social problems and social innovation and entrepreneurship are recognized as social inclusion mechanisms. These frames are levers for entrepreneurship and social innovation. However, challenges regarding complexity of instruments, ambiguity about law, and external pressures contribute to make some of the field actors questioning its credibility, avoiding entering in the field, hindering its grow.

On the one hand, actors advocate for the frame that social innovation and entrepreneurship are social inclusion levers and contribute to solve social problems. One government agency leader relayed that Social Innovation Fund (SIF), which is a Portuguese mechanism to incentivize entrepreneurship, has to be provided only to the north, center, and Alentejo, regions performing a per capita GDP lower than 75% of the European average (government agency leader). A law office leader stated that entrepreneurship incentives are a way of shifting the paradigm of philanthropy as the way to change the world (law office leader).

An impact fund manager commented on how they act to reinforce the frame of impact investing as a good way to generate social impact: “As huge fortunes go from parents to children, they require Fund managers able to receive and invest their capital in social impact causes” (impact investing fund 1 manager).

On the other hand, many challenges obstruct consensus in the field. On the intermediaries side, complexity of instruments and ambiguity of the law are the main challenges. One of the interviewees argues that “the variability of instruments and high number of actors involved in operations - such as SIBs - brings too much complexity on understanding of its modus operandi. “Reducing complexity management in relation to SIBs is necessary to improve impact investment” (execution service provider–coordinator).

Another problem is ambiguity of the law that regulates social enterprises receiving resources from impact funds. Actors state that “Legal framework is maladjusted in relation to the operational needs of the model. Social Enterprises cannot sell equity because they do not have booked social capital” (foundation former manager). As a consequence, if an investor or the government wish to invest in participation of these enterprises, they are not able to do that.

Finally, external pressures are exerted by the enormous bureaucracy of the European Union, jeopardizing the field settlement. “These pressures promote bad and time consuming governance. The bureaucracy is huge - every time they define a bid, we need to negotiate it with operational program, technical team, in Brussels. All the negotiation takes more than a year” (government agency leader).

The Dual Frame of Financial Return and Social Impact Is not Enough as a Mechanism to Legitimate Social Entrepreneurship in the Field

Levers for entrepreneurship legitimation in the field are financial return and social impact as legitimate to guide their practices, but scepticism from supply and demand side is still a challenge.

Impact funds managers, governance units created by the state as government agencies, and small banks play the role of capital suppliers. As such, they recognize financial return and social impact as legitimate to guide their practices. An impact fund manager asserted that “Future financially sustainable projects are expected to provide returns near the international VC ratios (15 to 20%)” (impact investing fund 1 manager). A foundation leader completed the argument, stating that, “We monitor social impact through indicators” (Foundation 2 leader).

However, they face resistance and scepticism from traditional financial sector as potential investors at the supply side and from NGOs and from demand side. On the supply side, one impact fund manager mentioned that most traditional financial banks do not invest in impact business because they do not believe on potential financial returns of impact funds: “There is a natural skepticism ... It is normal .... Not everyone has a penchant for social enterprise” (impact investing fund 1 manager).

On the demand side, selection criteria for investees are questioned as legitimate. NGOs argue that, “At the selection process, not all organizations should be treated in the same way. We handle social problems and not all of our projects generate revenues” (NGO leader).

As Formation Dynamics of the Field, actors Define its Roles and Mobilize to seize Opportunities to Partner with the State

As the field is formed, actors define roles and mobilize to foster social entrepreneurship, clearly following the construction of a new frame. They see themselves, not only as the ones who play relevant roles, but also mobilize to build the frame of being able to replace the role of the state. By its turn, the state corroborates the new policy approach, changing its role to be an asset manager, instead of grant maker.

On the supply side, investors want to be seen playing multiple roles (investor, partner, facilitator, innovator, socially responsible) as well as promoters of social inclusion:

“We hope to be useful in all places. We are market leaders in social economy. We are innovative. We are investors, facilitators, social partners for entrepreneurs and NGOs requiring funds.” (Mutualist financial institution leader)

Another identified him/herself as an ecosystem developer: “From 2013-14 we generated an innovative type of funding and created a social innovation lab. At that time, Impact investing was not relevant. We identified potential, opportunity to bring social impact when initiative was required.” (Foundation 1 leader)

Scholars also Play Their part in the Game:

“The academia is studying metrics, law, rebuilding social support mechanisms, predicting new forms of social response, which are not traditional ones” (former ministry member).

And the state, change its position: “The state armed itself. It is not anymore only grant making and giving but asset manager with a mission” (Foundation 1 leader)..

Emergent Mobilization of Actors Is Orchestrated by the State and Social Skilled Actors

At first, we see that the state, since 2006, has creating partnerships with actors, and conditions for the field emergence, by launching the Equal Program, the first program for social innovation and entrepreneurship in Portugal.

“With Equal, a network was built, although quite expensive and difficult to implement programs aims. When Equal disappeared (2008), the network dismantled, but the know-how falls asleep in people who participated in the program.” (Former ministry advisor)

Through an emergent mobilization, different actors were included in the process of ecosystem building. Demand side and intermediaries, such as consulting companies or third sector members, made agreements to create necessary conditions for social entrepreneurship. At the demand side, some entrepreneurs made partnership with state (General Directorate for Education):

This Directorate sends an invitation to schools (investee clients) to register. Some entrepreneurs (investees) also made partnership with private and third sector to obtain funds. A public University made the Assessment Report of our businesses. (Investee manager)

Some of these actors see themselves filling a gap in the market: “…we understood that there was this gap - a sub setting of impact investing (social venture capital) where things have not advanced. No one went ahead; we saw an opportunity” (impact investing fund 1 manager).

At the same time, they see impact investing as a cost reduction strategy for the state: “Impact investing is turning unemployed into employed, changing a number of lives, reducing government costs (8.5 million Euros is the government cost with the unemployed)” (Investee 2 manager).

All these connections between actors’ interests are mechanisms constructed by social skilled actors or institutional entrepreneurs. In 2011, an academic actor with social skills led the initiative to bring the French business school INSEAD and the ISSE (INSEAD social entrepreneurship program) to Portugal, representing a pilot initiative to create and incubate social entrepreneurship projects. This actor was responsible for mapping social innovations and for launching and updating a social innovation laboratory in 2011 and 2014, respectively.

In 2014, a minister, another social skilled actor entered in the stage, dealing with European funds. “He had the perspective of the UK Big Society. He created an office to think about the theme of the European Funds” (former ministry advisor).

The State Facilitation Responds Demands by Acting Strategically and Operationally, Replacing Investors in the New Market

Facilitation by the state, in the field of Portuguese impact investing, occurs mainly through its Internal Governance Units (IGU)—secondary agencies or departments, but also directly, when the state acts directly through the ministries or the councils of ministries, with a more strategic role, through EMPIS. This leading agency works to replace potential investors who still prefer not to enter the field. The governmental investment agencies also work to enable the operationalization of the impact investment instruments created by them.

One interviewee informed that, “This Agency for investment performs financial and risk analysis, and verifies who the potential investors are. We do not act in the strategic front” (government agency for investment leader). Other two interviewees clarified how IGUs can act strategically:

“EMPIS was created in 2014, but between 2016 and 2017, EMPIS shifted its model from wholesaler (lending only to banks) to retailer, lending also directly to Social Entrepreneurship Initiatives, creating different instruments to foster the field.” (Scholar)

“Concerning impact funds, there is a Venture Capital with government equity that has the role to cover market failures, and act as an impact investing fund, if no private investors show interest in this market.” (A venture capital with government equity)

For their part, non-state organizations demand new instruments and public policies to foster entrepreneurship, rejecting the new political approach that calls for private initiative to occupy spaces in the field.

They require financial resources:

“The main government agency has only public capital for projects, but needs also private capital to fund it. The point is that private actors still follow a logic that is very associated with philanthropyFootnote 4, but not with impact investing. They would rather donate than invest in social causes.” (Former ministry member)

This requires also a different approach for different businesses models:

“The state must create other instruments to finance non-impact business models: NGOs must have different treatment. There is no way to put some cases into social business models requiring revenue generation from them.” (NGO leader)

Discussion

While there are consensual frames, there are also challenges to be overcome if the field of impact investing is to grow. All actors see the field as a good way to solve social problems, as well as social innovation and entrepreneurship as forms of social inclusion. However, complexity and ambiguities work to prevent reaching a consensus in the field. The legitimacy of the field is contested by sceptical actors who do not believe in its double objective of financial return and social impact, as well as by those who do not agree with the selection criteria for investees. The state struggles to balance the field, acting strategically and operationally, interacting with actors who mobilize to change the situation and occupy a relevant place in the field. Our process-based model (Fig. 2) shows the interactions between the dynamics of consensus around frames and actor mobilization, and how the state interacts with these two mechanisms.

In the next paragraphs, we will explain how the dynamics of consensus, formation dynamics, and state facilitation interact reciprocally to create the field of impact investing in Portugal (Fig. 2). A few propositions are created after discussions about the relationship between these dynamics. Proposition 1 concerns the relationship between dynamics 1 and 2, proposition 2 concerns the reciprocal connections between dynamics 2 and 3, and proposition 3 deals with the interference of dynamics 3 on dynamics 1.

Our study showed that there was no consensus among the actors, although the existing frames are recognized by all, which makes impact investing to be characterized as a field (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012). The frames adopted by the actors are unequivocal about the role of social entrepreneurship and social innovation as a good way to solve social problems. However, the way in which the actors see the complexity of the instruments and the ambiguity of the law as obstacles to the development of the field is not unequivocal. Furthermore, the dual purpose of impact investing (financial return and social impact) generates scepticism in traditional financial sectors. It is not clear what could motivate these actors to become or not to become impact investors and what criteria they use to assess the potential of ventures (Roundy & Day, 2017).

On the demand side, the rules of the game are also not accepted as legitimate by some actors. NGOs, for example, do not agree that selection criteria—based on scalability and profitability—should be the same for all, as they are not capable of generating revenue. When adopting a mainstream investment approach to select investees, impacts investors fail to turn some promises of social impact investing into practice (Bengo et al., 2021).

Simultaneously, the state struggles to build a network that mobilizes the traditional private sector to increase the supply of capital available in the field and potential demand side—entrepreneurs interested in the possibility of obtaining financial returns and generating social impact from the impact investment (Höchstädter & Scheck, 2015). At the same time, the interaction between actors and investment logics, although limited in practice (due to complexities and ambiguities), calls for concerted action and collaboration between them to foster social entrepreneurship (Lehner et al., 2014). The supply side, intermediaries such as law firms and consultancies, and part of the demand side (those social entrepreneurs in the private sector who receive investments) mobilize, joining forces to create products or services in the field, such as the twenty SIBs that exist today in Portugal (PSI, 2021).

Most of the actors define their roles and mobilize, occupying positions to fill the gap they recognize as left by the state and reinforcing an argument and a frame that their actions reduce the costs of the state. The ecosystem is also built with the collaboration between social skilled actors (Fligstein and McAdam, 2012) and the state, which changes its role to be part of the market as an asset manager. At this point, the system reveals a reciprocal relationship between construction of frames/logics, legitimation for social entrepreneurship, and definition of roles and emerging mobilization, represented by the arrow connecting boxes 1 and 2, in Fig. 2.

In this feedback relationship, mechanisms and dynamics are mutually reinforcing. While actors mobilize to take advantage of opportunities in the field and consolidate roles (box 2, Fig. 2), they reinforce and legitimate frames and positions, which in turn can corroborate or weaken these roles (box 1, Fig. 2).

Proposition 1:

Formation dynamics and consensus dynamics are mutually reinforcing. The actors mobilize, playing roles and reinforcing frames that legitimize the field.

Proposition 1A:

The definition of roles and the emerging mobilization of actors interfere with the consensus on the framing and legitimation of the field.

Proposition 1B:

The search for consensus around the frames reinforces the legitimacy of the field, changes roles, and the emergent mobilization approach.

These efforts are coordinated by the state. Such coordination implies integrating participants into interdependent efforts, linked to each other, giving structure to the system, and making it function as a connected group, rather than a collection of autonomous individuals (Roundy, 2019). While the state interacts with private and third sector (Brown & Norman, 2011; Bugg-Levine et al., 2012) creating strategic and operational agencies and departments to foster social entrepreneurship and innovation mechanisms, as well as financial support (through the SIF, for example), other actors such as foundations, impact funds and some intermediaries connect to create or finance new entrepreneurship initiatives (e.g. CDI, Academia do Codigo), as well as to obtain financial support from the state.

At the same time, these actors define their roles, seeking to be seen as facilitators and innovators (e.g. Foundation 1 and the mutualist financial leader), in order to partner with the state. Simultaneously, actors mobilize by making agreements to create the necessary conditions for social entrepreneurship. Demand side and intermediaries such as consulting firms or members of the third sector join forces to build social ventures (e.g. a social enterprise for education). In turn, the state acts as a facilitator through the IGUs, responding to the strategic, operational, and financial demands of certain groups, and also interfering in the way these groups define their roles.

These relationships are represented by the arrow connecting boxes 2 and 3 (Fig. 2)

Proposition 2:

Dynamics or state facilitation and formation dynamics are interdependent.

Proposition 2A:

State facilitation dynamics integrates actors that mobilize and redefine their roles

Proposition 2B:

Actors mobilize and define their roles interfering in the state action.

These reciprocal relationships between the state and other actors in the field instigate social skilled actors to defend changes in legal frameworks and changes on external pressures (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012). One of these actions was the change in the model of the state’s main social innovation agency (EMPIS), from a wholesaler (loan only to banks) to a retailer (direct loan to social entrepreneurship initiatives). This action contributes to increase the number of investors and is a response to resistance from the private sector to invest in the area (Then & Schmidt, 2020).

On the other hand, there are contradictions within the state. As Fligstein and McAdam (2012) warn, the state is not a homogeneous body. An example of an internal contradiction is the absence of a legal model for non-profit social enterprises to receive funds via SIF equity, since they do not have booked social capital, thereby making impossible the selling of part of its capital as equity. As a result, an unclear and incomplete message is transferred to philanthropy and private investors (arrow connecting boxes 3 and 1, Fig. 2). As stated by Höchstädter and Scheck, 2015, 2-3) there are “critical issues that need to be clarified to advance in legitimizing the field of impact investing and increase its credibility”

The field seems to look for stabilization based on few instruments and internal governance units created by the state for levelling the field for players and reinforce supply side, following the market logic. However, on the demand side, there is a claim for a logic that embed economic action into the social (Then and Schmidt, 2020), one that must be answering in order to not risk to offer solutions, without considering social demands.

These relationships are represented by the arrow connecting boxes 3 to 1 (Fig. 2).

Proposition 3:

State facilitation interferes with the dynamics of consensus formation in the field.

Proposition 3A:

State investment in social entrepreneurship helps to reinforce the framework that social innovation and social entrepreneurship promote social inclusion.

Proposition 3B:

Coherence in the legal, operational, and strategic actions of the state can contribute to the legitimation of the field and encourage investors.

Final Considerations

We intend to contribute to better understanding of strategies and processes leading to the emergence of impact investing field and social entrepreneurship, considering relationships between foreign and regional actors.

This study is one of the first to provide a process-based approach on dynamics of impact investing field, and the findings reported here are likely to support decision makers and researchers in their impact investing initiatives aiming to favour social entrepreneurship as social innovation. We proposed a process-based framework that calls attention in a structured way to certain connections between endogenous and exogenous forces in the field, with special attention to the role of the state to foster social innovation, entrepreneurship, and social demands. We believe that different contexts deserve different analysis by considering its specificities.

Notes

SIB: The State hires the private sector, pre-setting an amount to be paid, if the project achieves certain levels of success. The compensation is based on budget savings for the State. If the project does not achieve the expected result, the burden will be on the private investor (Broccardo et al., 2020).

Elite informants are key decision makers who have extensive and exclusive information and the ability to influence important firm outcomes (Aguinis & Solarino, 2019).

The ESI F programming cycle of 7 years, usually defined by the European Commission to support European countries

In Portugal, 20% of companies make donations. Total volume ~ 300 M € (Portugal Inovação Social, 2019).

References

Aguinis, H., & Solarino, A. M. (2019). Transparency and replicability in qualitative research: The case of interviews with elite informants. Strategic Management Journal, 40(8), 1291–1315.

Agrawal, A., & Hockerts, K. (2021). Impact investing: Review and research agenda. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 33(2), 153–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2018.1551457

Alijani, S., & Karyotis, C. (2019). Coping with impact investing antagonistic objectives: A multistakeholder approach. Research in Int. Business and Finance, 47(C), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2018.04.002

Barber, B. M., Morse, A., & Yasuda, A. (2021). Impact investing. Journal of Financial Economics, 139(1), 162–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2020.07.008

Bengo, I., Borrello, A., & Chiodo, V. (2021). Preserving the integrity of social impact investing: Towards a distinctive implementation strategy. Sustainability, 13, 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052852

BEPA – Bureau of Economic Policy Adviser (European Comission). (2011). Empowering people, driving change - Social innovation in the European Union. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2796/13155

Block, J. H., Hirschmann, M., & Fisch, C. (2021). Which criteria matter when impact investors screen social enterprises? Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101813

Bozhikin, I., Macke, J., & da Costa, L. F. (2019). The role of government and key non-state actors in social entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 226, 730–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.076

Brandstetter, L., & Lehner, O. M. (2015). Opening the market for impact investments: The need for adapted portfolio tools. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 5(2), 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2015-0003

Broccardo, E., Mazzuca, M., & Frigotto, M. L. (2020). Social impact bonds: The evolution of research and a review of the academic literature. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(3), 1316–1332.

Brown, A., & Norman, W. (2011). Lighting the touchpaper. Growing the market for social investment in England. The Boston Consulting Group. Retrieved February 18, 2022 from https://youngfoundation.org/publications/lighting-the-touchpaper-growing-the-market-for-social-investment-in-england/

Bugg-Levine, A., Kogut, B., & Kulatilaka, N. (2012). A new approach to funding social enterprises. Harvard Business Review, 90(1/2), 118–123. Retrieved February 15, 2022 from https://philanthropynetwork.org/sites/default/files/7.%20A%20New%20Approach%20to%20Funding%20Social%20Enterprises.pdf

COM (2011)0682. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Social business initiative. Creating a favourable climate for social enterprises, key stakeholders in the social economy and innovation {SEC(2011) 1278 final} (2011, October 25). Retrieved February 14, 2022 from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0682:FIN:EN:PDF

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitati ve Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (3rd edn). Sage: London, UK.

Daggers, J., & Nicholls, A. (2016). Academic research into social investment and impact investing : The status quo and future research. In Routledge Handbook of Social and Sustainable Finance. Routledge.

Davies, A., Mulgan, G., Norman, W., Pulford, L., Patrick, R., & Simon, J. (2012, December 1). Systemic innovation, social innovation. European Comission. Available at https://www.siceurope.eu/sites/default/files/field/attachment/SIE%20Systemic%20Innovation%20Report%20-%20December%202012_1.pdf. Acessed 19 Nov 2022.

de Bruin, A., Shaw, E., & Lewis, K. V. (2017). The collaborative dynamic in social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(7-8), 575–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1328902

Dohrmann, S., Raith, M., & Siebold, N. (2015). Monetizing social value creation: A business model approach. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 5, 127–154. https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2013-0074

Dowling, E. (2017). In the wake of austerity: Social impact bonds and the financialisation of the welfare state in Britain. New political economy, 22(3), 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1232709

Ferreira, S., Fidalgo, P., Giovannini, M., Almeida, J., Pinto, H., Lima, T. M., Ramos, M. E., & Ferreira, V. (2021). Trajetórias institucionais e modelos de empresa social em Portugal. CES – Universidade de Coimbra.

Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2012). A theory of fields. Oxford University Press.

Geobey, S., Westley, F. R., & Weber, O. (2012). Enabling social innovation through developmental social finance. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 3(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2012.726006

GIIN. (2021). Global Impact Investing Network. In Annual impact investor survey (11th ed.). Retrieved February 12, 2022 from https://thegiin.org/research/publication/impact-investing-market-size-2022

Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative health research, 27(4), 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2012). Seeking qualitati ve rigor in inducti ve research: Notes on the GioiaMethodology. Organizati onal Research Methods, 16(1), 1–17.

Höchstädter, A. K., & Scheck, B. (2015). What’s in a name: An analysis of impact investing understandings by academics and practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(2), 449–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2327-0

Huybrechts, B., Nicholls, A., & Edinger, K. (2017). Sacred alliance or pact with the devil? How and why social enterprises collaborate with mainstream businesses in the fair trade sector. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(7-8), 586–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1328905

Lall, S. (2019). From legitimacy to learning: How impact measurement perceptions and practices evolve in social enterprise–social finance organization relationships. Voluntas, 30, 562–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-00081-5

Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24, 691–710. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2553248

Lehner, O. M., & Nicholls, A. (2014). Social finance and crowdfunding for social enterprises: A public–private case study providing legitimacy and leverage. Venture Capital, 16(3), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2014.925305

Maduro, M., Pasi, G., & Misuraca, G. (2018). Social impact investment in the EU. EUR 29190. EN, Publications Office of the European Union.

Mangram, M. E. (2018). ‘Just married’ – clean energy and impact investing: a new ‘impact class’ and catalyst for mutual growth. The Journal of Alternative Investments, 20(4), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.3905/jai.2018.1.061

Martin, M. (2015). Building impact business through hybrid financing. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 5(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2015-0005

McWade, W. (2012). The Role for Social Enterprises and Social Investors in the development struggle. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2012.663783

Mendes, A.M.SC., & Pinto, F.N.C.B. (2018). Importância económica e social das IPSS em Portugal. CNIS – Confederação Nacional das Instituições de Solidariedade Social.

Michelucci, F. V. (2017). Social impact investments: Does an alternative to the anglo-saxon paradigm exist? Voluntas, 28, 2683–2706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9783-3

Mollinger-Sahba, A., Flatau, P., Schepis, D., & Purchas, S. (2020). New development: Complexity and rhetoric in social impact investment. Public Money & Management, 40(3), 250–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1714318

Miles, M., & Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitati ve Data Analysis. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Morse, J. (2000). Determining sample size [Editorial]. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 3–5.

Mulgan, G. (2015). Social finance. Does ‘investment’ add value? In A. R. Nicholls, Paton, & J. Emerson (Eds.), Social finance (pp. 45–63). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198703761.003.0002

Nicholls, A., & Emerson, J. (2015). Social finance: Capitalizing social impact. In A. R. Nicholls, Paton, & J. Emerson (Eds.), Social finance (pp. 1–41). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198703761.001.0001

OECD/European Union. (2017). Portugal Inovação Social: An integrated approach for social innovation. In Boosting Social Enterprise Development Good Practice Compendium (pp. 169–177). OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019). Social impact investment 2019: The impact imperative for sustainable development. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264311299-en

Pettigrew, A. M. (1990). Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organization Science, 1(3), 267–292. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2635006

Phillips, S. D., & Johnson, B. (2021). Inching to impact: The demand side of social impact investing. Journal of Business Ethics, 168, 615–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04241-5

Pirson, M. (2012). Business models and social entrepreneurship. In H. K. Baker & J. R. Nofsinger (Eds.), Socially responsible finance and investing: Financial institutions, corporations, investors, and activists (pp. 2–20). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118524015.ch4

PSI. Portugal social innovation. (2021, October 20). Mapa Interativo da Inovação Social. https://inovacaosocial.portugal2020.pt/projetos/

Quinn, Q. C., & Munir, K. A. (2017). Hybrid categories as political devices: The case of impact investing in frontier markets. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 51, 113–150.

Ramesh, S. (2020). Entrepreneurship in China and India. Journal of Knowledge Economy, 11, 321–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-018-0544-y

Regulation (EU) No 346/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council European Social Entrepreneurship Funds. (2013, April 17). Official Journal of the European Union, L 115, pp 18–38. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R0346&from=en

Regulation (EU) 2017/1991 (2017) Amending Regulation (EU) No 345/2013 on European venture capital funds and Regulation (EU) No 346/2013 on European social entrepreneurship funds. (2017, November 10). Official Journal of the European Union, L293, 1–18. Retrieved February 22, 2023 from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32017R1991

Resolution of the Council of Ministers. (2014). Criation of Estrutura de Missão Portugal Inovação Social (EMPIS)., 73-A. (2014, Dezember 16). Republic Diary No. 73-A/2014, Series 1, pp 6130-(2) a 6130-(4). Retrieved March 20, 2023 from https://dre.pt/dre/en/detail/resolution-of-the-council-of-ministers/73-a-2014-65908878

Rexhepi, G. (2016). The architecture of social finance. In O. M. Lehner (Ed.), Routledge Handbook of Social and Sustainable Finance (pp. 35–49). Routledge.

Rodin, J., & Brandenburg, M. (2014). The power of impact investing: Putting markets to work for profit and global good. Wharton Digital Press.

Roundy, P. T. (2019). Regional differences in impact investment: a theory of impact investing ecosystems. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(4), 467–485. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-11-2018-0302

Roundy, P., Holzhauer, H., & Dai, Y. (2017). Finance or philanthropy? Exploring the motivations and criteria of impact investors. Social Responsibility Journal, 13(3), 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-08-2016-0135

Teddlie, C., & Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806292430

Tekula, R., & Andersen, K. (2019). The role of government, nonprofit, and private facilitation of the impact investing marketplace. Public Performance & Management Review, 42(1), 142–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2018.1495656

Tekula, R., & Shah, A. (2016). Impact investing: Funding social innovation. In O. M. Lehner (Ed.), Routledge Handbook of Social and Sustainable Finance (pp. 125–136). Routledge.

Then, V., & Schmidt, T. (2020). Debate: Comparing the progress of social impact investment in welfare states—a problem of supply or demand? Public Money & Management, 40(3), 192–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1714302

Vogt, W. P. (1999). Dictionary of statistics and methodology: A nontechnical guide for the social sciences. Sage.

Zivkovic, S. (2017). Addressing food insecurity: A systemic innovation approach. Social Enterprise Journal, 13(3), 234–250.

Acknowledgements

Authors are deeply grateful for the contribution of all the interviewees, without whom it would not have possible to do this research. This work has been supported by the following Brazilian research agencies: FAPESP—grant 2018/10288-5. We acknowledge also Portuguese FCT funding support with multi-year research funding UIDB/04521/2020 (ADVANCE/CSG).

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This research involves interviews with human participants. The research followed the conduct of the institutions to which authors are affiliated. All participants had their identity preserved and were warned at the beginning of the interview that they could stop responding and that they had the right to refuse to answer any questions. All interviews were recorded, and the statement is at the beginning of them.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Christopoulos, T.P., Verga Matos, P. & Borges, R.D. An Ecosystem for Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation: How the State Integrates Actors for Developing Impact Investing in Portugal. J Knowl Econ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01279-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01279-9