Abstract

The global ascent of the knowledge economy has opened an unprecedented opportunity to value the earth’s evolutionary and ecological fabric as a transnational reservoir of latent scientific knowledge that could define this emerging economy as profoundly as oil has shaped the industrial economy. It has also uniquely positioned the international resort enterprise to bring science into the heart of a business model in which quality and prestige grow along with investments in geographically unrestrained scientific discoveries and which delivers formidable legacy dividends in its defiance of monopoly over the funded research. The article expands on these original assertions, the accomplishments they ignited, and the academic credentials that fortify them, with an emphasis on the business model’s capacity to build novel economic foundations for global conservation and to empower basic science at the most challenging scale above national jurisdictions where it merits designation as common heritage of mankind. It discloses how the resort sites’ label as premier real estate wastes many of these sites’ worth as crossroads of wonder-packed connections among variously distant ecosystems, geological formations, and other pillars of the earth’s architecture. It translates this disclosure into a blueprint, for new-generation resorts, of the power to align a private enterprise system with appreciation of knowledge as a precursor of future knowledge and, in the process, to chart a transformative course for the global knowledge economy. An island portfolio in the Gulf of Panama and the Hawaiian island of Lanai are profiled in their distinctive potentials to emblematize the rewards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A United Nations press release titled Using Luxury Tourism, Science to Rethink Potential of Knowledge Economy (September 17, 2010) announced a UN-sponsored event I was honored to organize to reveal a new economic model deemed by the release “an unprecedented opportunity to fortify a knowledge bank with incalculable value to strengthen and sustain the emerging global knowledge economy, one that could elevate the conservation of the planet’s most exquisite and vulnerable places into an economic imperative” (United Nations Department of Public Information 2010). A sequel, an international symposium themed The Economic Epic of Earth’s Evolution and co-hosted by the West Coast Headquarters of the United States National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the University of California, Irvine (UC Irvine) on February 7, 2014, generated this opportunity’s centerpiece: a resort business model that engages scientific research to chart a new geography, diplomacy, and conservation legacy for the knowledge economy (UC Irvine 2014).

These two events marked cherished milestones in a most rewarding professional-cum-personal journey. They also acted as springboards towards further consolidation and rigorous vetting of a mission I have pursued since the 1990s: a mission to lay the foundations for a new economic geography structured by transnational bridges of knowledge that value the presently economically uncharted yet uniquely unifying territory of the earth’s evolutionary and ecological fabric and the priceless knowledge resource woven into this fabric. This endeavor has involved two parallel foci.

One focus has been shaped by my assertion that the knowledge-based economy’s premise on investments in research parks, scientific cities, and knowledge-based industries leaves out a dormant mega-reserve of the strength and sustainability of this twenty-first century economy. This mega-reserve, I have argued, is contained in the still largely unspoiled landscapes and seascapes of our planet, involving such features as rainforests, coral reefs, and other spectacularly biodiverse habitats. I view these extraordinary natural environments, most opulent in the world’s tropics, as treasuries of the knowledge mineral—the “raw material” of potential scientific knowledge that could define this new economy as profoundly as oil has shaped the industrial economy, not replacing oil but vastly outperforming it in endurance and lasting benefit to humanity. The following comparison is crucial to this daring prediction. The global volume of oil, or mineral ores, is just a sum of their deposits across the world. In contrast, the knowledge mineral grows in volume and, importantly, worth in the context of transcontinental evolutionary and ecological relationships that have a great potential to yield scientific discoveries and to revolutionize basic scientific research. And, unlike oil or mineral ore deposits, which are depleted over time, these transnational veins of the knowledge mineral actually increase in volume and value the more they are explored and used.

The implications for sustainable development and conservation are profound. A new economic outlook could emerge for some of the world’s poorer nations that collectively hold a lion’s share of the mega-diverse natural environments harboring huge untapped possibilities for scientific exploration that can lead to new knowledge and wealth creation. Transnational conservation projects could acquire an unprecedented momentum and investment draw by becoming integral components of novel economic blocks whose member nations could rise as prominent players in the knowledge economy. However, these outlooks entail a critical pre-condition. They must elevate the open-ended scientific exploration that will drive them above its current dependency on and struggle for government funding, to the command of stature in the world of corporate and private investments—a stature fuelled by rewards other than immediate profit-making.

This position, which underpins the other core focus of my mission, has grown from my reflections on the work in economics that defines the distinctive properties of knowledge as a public good (see Nelson 1959 and Arrow 1962 as the classic references) and from a question I posed to myself: Is there an industry of global presence and of an existing or potential business model that could defy the established paradigm of the incompatibility of “private profit opportunities” and “knowledge as public good”? I have answered this question by positing that the international tourism industry, led by the resort industry, could deliver this singular exception. Central to this perspective is the disclosure of the unmatched potential of the resort enterprise to reap major business dividends from investments in geographically unrestrained, monopoly-free basic research endeavors and, in the process, uniquely to facilitate the transformative scale of the economic model that treats the knowledge-rich natural capital as a lifeline of the global knowledge economy.

In a recent article, I endeavored to deliver a comprehensive presentation of the aforementioned two foci: of the original economic and business models that were shaped by this process and of the key publications, endorsements, and other recognitions of these two models’ joint capacity to shepherd transnational units of sustainable development cemented by science diplomacy and guarding giant pools of natural riches as their most precious stock (Ayala 2017). Emphasizing the “strategic synergies” that intertwine these economic and business models, I assert that tourism-based economies and knowledge economies, viewed in conventional terms as two dramatically different scenarios of economic development, can be combined to yield a major new economic model since they share a resource base of critical importance to their strength and growth potential—a resource under threat and gradually disappearing throughout the world. At both the conceptual and applied levels, the article seeks to complement existing directions and achievements in environmental economics, international conservation, and other relevant fields, guided by the aspiration to introduce new angles and catalysts of their confluence towards facilitating sustainable prosperity that is powered by knowledge and nurtured by heritage.

The present article expands on the business model and its ambition to awaken the extraordinary potential of the global crop of environmentally progressive resorts and ecophilanthropy-minded private estates collectively to provide a logistical and investment foundation for building transnational knowledge economies that draw strength from and strengthen the world’s premier natural heritage reserves. Part I of this article, titled “Nature’s Connectivity as a Development Philosophy,” chronicles the business model’s evolution, the academic credentials it entails, and the assurances it acquired when tested in a variety of geographical and cultural settings. It unfolds from two powerful sources of inspiration that opened my eyes to major untapped reserves of the resort product and the international resort industry, namely, hotel concepts native to Japan and Spain (Ayala 1991a). This retrospective provides the foundation on which, in Part II, I introduce the “Transnational Resort: The Power Broker of a Genuinely Global Knowledge Economy.” With references to the latest relevant trends in the industry, this blueprint extends the notion of luxury to a provision of a striking new intellectual dimension that opens new frontiers for “legacy investments” and bases the criteria for flagship projects on their capacity to stimulate economically savvy science and conservation collaborations among nations, corporations, and institutions not yet perceived as strategic partners in the current scenarios of international trade.

Part I. Nature’s Connectivity as a Development Philosophy

Green Resort Without Borders

Throughout the world, the most magical and seductive settings for resort developments coincide with the ecosystems that harbor treasure troves of yet-to-be unearthed knowledge. More often than not, the views afforded by the resorts’ privileged locations offer rare exposures to marvel-saturated environments that are either generally inaccessible or so vulnerable as to restrict severely or even preclude visitor access.

This observation led me to reflect on the travels and research that exposed me to icons of the technique of shakkei (“borrowed scenery,” “landscape captured alive”), mastered in Japanese garden art. This technique is boundless in bringing the beauty of variously distant natural environs directly into the layout of the garden, with no physical incursion into these areas. The Pure Land Gardens of Hiraizumi, focused on the sacred mountain Mount Kinkeisan and honored by UNESCO with the World Heritage recognition, offer the ultimate testimony to the might of shakkei-spirited landscape artistry.

Several of the ryokan—the traditional inns of Japan that now offer first-rate accommodations—integrate shakkei technique in their distinctiveness and strong sense of place. Since these two qualities are also important objectives of many resort master plans, a shakkei-inspired approach to transforming the scenery from being an asset of the site to becoming a defining element of the resort’s place-unique identity offers a valuable direction for resort design. However, appropriating a view of the resort destination’s land and marine surroundings merely as scenery would leave out the view’s information content—an untapped resource that could fuel interpretation-assisted, enlightening, and utterly sustainable encounters with landscapes and seascapes both within and beyond visual reach, taking the resort industry’s “greening” effort to an entirely new level of reach and benefit, across geographies.

The mobilization of this resource is conditioned on the recognition that intriguing affinities and connections can often be drawn between the ecosystems that envelope the resort’s choice setting and those in need of lasting protection in other parts of the host country or region. A strategic alliance that would enable the resort to provide ever richer insights into these affinities via ongoing access to their scientific exploration would reward the resort’s patrons with first-class intellectual pleasures, continuously upgraded in novelty and educational value. Importantly, it would encourage the resort’s active, and most marketable, patronage of variously distant pools of natural heritage riches with no actual physical impact by guests.

I integrated these arguments into three core principles—and design management solutions—that, in their interplay, would distinguish an ecoresort product from a resort product: the resort-plus scope of master-planning, an expanded capacity to assimilate, and a layered approach to product development (Ayala 1991b, 1995a, 1996a). While endeavoring to become self-contained and self-sustainable as a “closed” system in terms of re-use and recycling, with minimized demand on the destination’s non-renewable or scarce resources, an ecoresort ought to achieve the greatest possible “openness” between the components owned by the resort and those “borrowed.” I elevated the goal and techniques to maximize the capacity to “borrow,” rather than develop, landscape resources to be the driving element of the ecoresort master plan from the point of view of both the environmental and business benefits.

Taking into account the accelerating confluence of international tourism and international ecotourism, which manifested itself particularly in long-haul leisure travel and which made “resort ecotourism” a conceptual framework of enormous business and conservation potential (Ayala 1996b), I planted a vision of an unprecedented partnership of the international resort industry, heritage conservation, and sustainable development (Ayala 1995b). Two trail-blazing accomplishments achieved and perpetuated in the field of cultural heritage by Spanish paradors, made up in large part of historical monuments-turned-hotels, were instrumental in inspiring this vision and in awakening me to another major uncharted opportunity for the resort industry, science, and sustainable development.

The parador network’s systematic and successful effort to revive routes of civilizations, religions, and arts that cut across Spain and are magnets for travelers serious about exploring that country’s history and geography and which bestow an extra layer of interest and value on each parador product is one of those inspiring accomplishments. The other is the uniquely pro-active force of paradors’ patronage of culture: it does not just bring back to life past cultural achievements—it gives birth to new ones. A two-volume literary masterpiece featuring essays written about individual parador destinations by preeminent Spanish writers deeply versed in the culture of the corresponding regions (Secretaría General de Turismo 1986)—and translated into many languages—is an impressive example of the energy and national benefit that paradors collectively exert far beyond the fields of hospitality and heritage conservation. No comparable achievement exists at the interface of the hospitality industry—resort industry, in particular—and the natural world, be it on national, regional, or global levels.

Invitations from two countries, Fiji and Panama, allowed me to proceed with developing and testing a sustainable development model in which nationally scaled strategies of tourism, conservation, and research are pro-actively planned to grow in a mutually reinforcing relationship bonded by multi-hotel portfolios.

Tourism-Conservation-Research Infrastructure for a Nation’s Future

Fiji: the “TCR” Drawing Board

It is with gratitude that I recognize the late Michael J. Kemp, then general manager of the Regent of Fiji, for embracing my vision of an economic opportunity that would be powered by Fiji’s spectacularly diverse natural heritage, aided by science, and championed by the hotel industry. I am also indebted to him for mediating my vision’s exposure to that country’s political and business leaders.

The project I undertook at the invitation from the Fijian government revealed an astounding potential for added value that has been missed in the planning and development of that country’s tourism economy, notwithstanding Fiji’s offer of a number of upmarket resorts praiseworthy for their environmental and cultural sensitivity and contribution to conservation. This potential is rooted in the startling—yet, beyond academia, little known—array of island types, ecologies, geological formations, and fossil records that defines this South Pacific nation of more than 350 islands.

There are high and low islands, volcanic and limestone islands, islands that are rising and islands that are subsiding, and many other expressions of that country’s intricate geology that, in turn, accounts for fascinating diversities of climate and biodiversity. Innumerable examples of all stages in the development of oceanic coral reefs pervade the waters of the Fijian Archipelago. It is only at the level of the entire country that one can appreciate the attributes that, together, make Fiji an ideal laboratory for understanding the processes of island and coral reef formation over millions of years, for illustrating the profound impact of plate tectonics, and for many other insights into this monumental pool of knowledge of global significance.

Heritage themes, vigorously explored by science, would fortify the mesh of natural wonder that crisscrosses Fiji. Combined with the “ocean roads” of traditional cultures and their legacies, they would provide a unique foundation upon which Tourism, Conservation, and Research (“TCR”) could be master-planned to grow together and in support of the nation’s transformation into a premier “heritage destination” that is fed by a knowledge laboratory of value to various sectors of the economy (Ayala 1995c).

I have concluded that the scientific value of a nation’s heritage bounty could become the nation’s—and the industry’s—principal economic resource. Fiji inspired this position. Panama anchored its transformation into action.

Panama: “TCR” in Action

Panama is a meeting place of oceans and a bridge between continents, packed with spectacular botanical and faunal diversity. The country is also the seat of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), a bureau of the Smithsonian Institution, which has produced one of the most extensive databases available in the tropics. STRI’s research has zoomed in on the Isthmus of Panama and the surrounding littoral as unmatched models for evolutionary and biogeographical studies that may enable scientists to predict future changes of the tropical ecosystems.

Panama’s natural wealth of immense scientific importance, combined with the presence of STRI, are is the strongest cards Panama holds for building sustainable prosperity and international prestige and image. These two cards make Panama an ideal venue for forging a model TCR alliance and fashioning this alliance into an engine of a knowledge-powered economy that is nurtured by the country’s singular heritage identity.

An article in which I articulated these arguments and proposed an implementation strategy (Ayala 1997) was instrumental in prompting a national project, the TCR Action Plan for the Republic of Panama, at the invitation of the Panamanian government. I will highlight only the key outcomes pertinent to the subject of the present article.

The overall achievement of this TCR flagship (Ayala 1999, 2000a, 2004a, 2004b; Aguilar and Saied 2004) is first and foremost about the success in employing the TCR model’s core instrument of heritage themes to capture and extol the unrivaled geological, ecological, and cultural dynamics and complexity of Panama in a manner that simultaneously augments the scientific, conservation, and economic (particularly tourism) values of the interlinked heritage resources. STRI’s support and expertise ensured a cutting-edge outcome: a network of 23 heritage routes based on themes that span Panama on various spatial scales and which reach millions of years back in time, supplying an original instrument for presenting, protecting, and enhancing the national heritage while energizing the national economy.

Related and concurrently executed priorities were to ally government leaders of the most relevant sectors—in particular, tourism (Tribaldos 1998), environment (Endara 1998), and science (Sánchez 1998)—to bring STRI into this team (Rubinoff 1998), and to formalize this collaboration, as delivered by the Presidential Decree No. 327 engineered by the TCR Action Plan.

It was within this net of opportunities and safeguards that a pilot union of TCR hotel partners was formed and paired with leading-edge, conservation-relevant research, setting a precedent for hotel stewardship (Ayala 1998, 2000b). Concurrently, the Action Plan spotlighted one-of-a-kind opportunities for enlightened hotel investments along the TCR heritage themes. For example, as revealed by The Saga of the Isthmus theme, sediments saturated with preserved marine fauna and embedded in striking coastal exposures make the Bocas del Toro island group in Panama’s Caribbean a testament to the most complete history of the evolution of tropical marine life over the last 20 million years. This distinction—and inimitable competitive edge—would be shared by a resort project that would embrace this theme and the research behind it as catalysts of a heritage experience not replicable anywhere else in the world. Simultaneously, that same resort could take this singular experience to an even grander scale along The Route of the Three Oceans, which pairs the resort’s Caribbean/Atlantic Ocean setting with two distinctive oceanographic zones discovered on Panama’s Pacific side. The business rewards of such a move would generate rich dividends for science and conservation. Comparative genetic studies that would be carried out simultaneously in these “three oceans” of Panama would be of major significance for deciphering species evolution and adaptation.

This brings me to a distinctive characteristic of the heritage matrix I planted in Panama, namely, that it creates opportunities for the tourism and hotel industry as part of a larger opportunity for the nation. Three models of heritage-themed facilities set within the conceptual framework of the TCR Action Plan and designed by the acclaimed architect Frank O. Gehry (FOGA, Inc. 1999; Aguilar and Saied 2004) added a formidable reassurance and source of synergy. Areas plagued with poverty in parts of Panama, which, paradoxically, nearly invariably overflow with heritage wealth, emerged as superb T-C-R crossroads. A “TCR Cluster” of interdisciplinary studies, designed in collaboration with Panama’s City of Knowledge, offered a blueprint for a capacity-building academic program that would aid the TCR opportunity’s fulfillment in Panama and regionally. The coverage of the TCR Action Plan by influential media—ranging from Hotels (Miller 1999), Architecture (Hart 1999), and Condé Nast Traveller UK (D’Arcy 1999) to Science (Ayers 1999), Scientific American (Nemecek 1999), and Civilization, the magazine of the Library of Congress (Hogrefe 1999/2000)—cemented the foundations this project laid for distinguishing Panama, and Panama’s hotel industry, as stewards of a new-generation economy that values and secures the country’s greatest reserve of competitive strength: its heritage riches.

Formally endorsing the TCR model and its application in Panama on behalf of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Richard Nicholson, then CEO of AAAS, emphasized the TCR’s potential to use science in the promotion of human welfare and human progress on a scale that could not otherwise happen (Nicholson 1999).

Harnessing this potential on a national scale is just a tip of the iceberg. For me, the most consequential outcome of the Fiji- and Panama-scaled designs of the TCR union was the recognition that restricting such a union within a nation’s borders only scratches the surface of the opportunity for the industry, for the environment, and for humanity.

Part II. Transnational Resort: the Power Broker of a Genuinely Global Knowledge Economy

The greatest opportunities for advancing human welfare and human progress may well exist in insights into hidden connections or relationships between pre-existing elements. However, seeing the bigger webs of connections is a formidable challenge. Scheffer and van Nes (2018) point to an analogy from the financial world, when, after the collapse of the financial services firm Lehman Brothers, the global cascade of events ran through a network of connections between banks and other financial institutes that was largely hidden from the public eye. They conclude that understanding complex systems as a whole—and seeing a global web of connected systems—is crucial if we want to understand resilience and regime shifts, be it in the biosphere or in the human body.

The geography of wonder fashioned by nature is blind to political lines. Panama’s natural capital and its wonder content are intertwined with those of the entire Central American land bridge and with those of Colombia, Costa Rica, and Ecuador in the marine realm, along a biological corridor fuelled by the convergence of major oceanic currents and nurturing a spectacularly diverse marine life. Fiji’s dormant economic potential as an unparalleled heritage bank and ecological theater grows in promise and magnitude amidst the daunting diversity and complementarity of natural environments all across the Pacific island ecosystems and beyond. These transnational paths of wonder superbly lend themselves to environmentally enlightened business capitalization. They are dormant engines of exceptional heritage experiences, expandable across the globe in both content and influence on changing the perception and future of the currently economically marginalized heritage-rich habitats whose untapped economic worth is in the knowledge they contain.

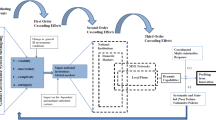

This position is at the heart of the mission of the Pangea World organization I founded (Ayala 2003; Lempinen 2006; Lew 2007; Loose 2013; Wiesnerová 2013). And from the platform of Pangea World, I have embarked on equipping this position with a “supra-structure” of guidance and facilitation that spans and blends three fronts. On the science front, the goal is to enact a dynamic web of trans-regional, cutting-edge research agendas whose promise to advance the frontiers of knowledge by unmasking the connectivity among variously distant threads of the earth’s natural fabric is not backed by the existing financial and logistical mechanisms of support for science. On the diplomacy front, the strategy is to build recognition and stature for these science-mapped, national jurisdictions bridging veins of the knowledge mineral and, thus, plant safeguards of the enhanced value and prestige that would reward a new breed of resorts master-planned (new projects) or allied (existing properties) as gateways into far-reaching labyrinths of wonder. On the knowledge economy front, the priority is to demonstrate that transnational research of natural legacies conducted under the umbrella of investments in world travel uniquely invites the treatment of the mobilized knowledge as a global asset destined to benefit all of humanity, since such an approach will further augment the involved investors’ influence on shaping business, philanthropic, and political leadership in our ever more knowledge-oriented world. It is at the crossroads of these three fronts that wonder meets legacy in a hospitality paradigm of infinite scale and appreciation potential. I have named that paradigm transnational resort.

A Momentous Synergy: the Evolving Encounter of Resort Business and Ecophilanthropy

Responsible luxury, conscientious luxury, and sustainable hospitality are among the terms that have become prominent definers of the quality of the hotel product and its competitive market position. In terms of its marketing muscle and financial capacity to shape this trend, the industry’s top-tier resort segment is worthy of a special look. The location on Baa Atoll, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, combined with the stewardship of manta rays research, coral reefscaping, and sea turtle protection aided by a marine discovery center, plays prominently in the positioning of the Four Seasons Resort Maldives at Landaa Giraavaru. Elsewhere, a commitment to protecting and championing the extraordinary marine environment of the Northern Lau Group of Fiji highlighted highlights the dimensions of the “ultra-luxury” of the Vatuvara Private Islands Resort on Kaibu Island.

I have observed ever stronger affinities between the growing emphasis that upscale resort developments place on blending exclusivity with research-courting environmental initiatives and the growing trend of pairing ecophilanthropy with a hotel-anchored business model. Most ecophilanthropic ventures involve conservation- and restoration-centered purchases of often vast swaths of natural areas. These land acquisitions or private concessions, and the biological and ecological research carried out within their boundaries, are increasingly complemented with environmentally minded hotel projects that become one—in mission and distinction—with these formidable expanses of private reserves. Inkaterra Reserva Amazónica, an “eco-luxury” lodge nestled within a more than 40,000-acre private concession adjacent to the biologically lush Tambopata National Reserve, set a precedent in 1970s when it was born as a visionary combination of a private reserve, then a small tourist lodge, and an environmental research center in the Peruvian Amazon (Dunford 2007; Rush 2005). The Mashpi Rainforest Biodiversity Reserve, a private concession spread across close to 3,000 acres of the cloud forest of the Ecuadorian Andes and now complete with the accolade-winning architecture of Mashpi Lodge, is a more recent example of the potential of blending conservation, science, and commerce in some of the biologically richest and fast disappearing places on earth (Doerr 2011).

The progressively blurred line between resort business and ecophilanthropy is no less detectable and laudable in the marine context. Misool Eco Resort is the perfect “ambassador” of a project that has transformed hundreds of square kilometers of ocean into a marine protection zone in the Indonesian archipelago of Raja Ampat (Chan 2015). Deservingly, it is included in a recent spotlight on nine eco-resorts whose status of “exceptional” is exemplified by their passion about “giving back in a big way” (Murphy 2016). The other profiled properties range from Leonardo DiCaprio’s Blackadore Caye off the coast of Belize (a “Restorative Island,” see also Satow 2015), Petit St. Vincent Resort, and The Brando on the Tetiaroa atoll in French Polynesia to island properties off the coasts of Tanzania (Thanda Island), Mozambique (AndBeyond Vamizi Island and Anantara Bazaruto Island Resort), Madagascar (Miavana), and Cambodia (Song Saa Private Island).

Each is a trail blazer in giving back to the benefit of coral reefs and marine life in its respective region. But each is also well positioned for an even grander ambition, as are like-minded properties in naturally privileged land settings. Each holds the potential to generate business and legacy premiums through investments in exploration and disclosure of wonder-rich relationships that tie their respective destinations’ natural wealth, and its research worth, to natural cradles of the knowledge capital across regions and political borders. The pursuit of this potential would be most conducive to partnerships of shared capacity to pioneer daring cross-national science and conservation initiatives in a pragmatically effective and economically sustainable fashion.

Such partnerships could also greatly facilitate science-guided protection of species whose migrations transcend multiple states’ exclusive economic zones and areas beyond national jurisdictions. Havice et al. (2018) examine a novel scientific approach that addresses the global extinction risks for endangered marine turtles via interlinked regional assessments whose scales—and goal to serve as “regional management units”—are defined by the turtles’ migratory patterns. This examination is of utmost relevance, contributing most notably in the attention it draws to the work of science and scientists in making ocean resources legible and therefore governable.

A Business Model that Renders Real Estate Values Obsolete

Partha Dasguptas’s groundbreaking work in economics offers an intriguing synergy. As Doctrow (2016) notes, Dasgupta, an economist at the University of Cambridge, realized that the economic models were neglecting an entire class of capital assets: natural resources. Over the course of his career, he has worked to put “natural capital” on an equal footing with other capital assets: he has advocated for measuring the strength of national economies based on their “inclusive wealth,” which includes the value of natural capital alongside infrastructure and human capital.

In the resort context, I argue, science holds the key to unlocking the “inclusive worth” of the resort sites—worth whose “inclusiveness” also extends to far-reaching environmental and social dividends.

Let us re-enter the world of crème de la crème locations for resort developments, from private islands set in some of the world’s most pristine marine environments to secluded tropical coasts fringed by rainforests and coral reefs and to other ever-scarcer habitats of natural wonder and beauty. These magical locations figure in the global resort-investment market as merely premier real estate, grossly underappreciated and undervalued by the failure to recognize and value many of these locations’ quality as unmatched crossroads of wonder-packed connections among variously distant ecosystems, geological formations, and other pillars of the earth’s architecture. I venture to suggest that the potential of a prospective resort site to serve as a portal into a range of such connections is of an even greater value for the site’s business and legacy capitalization than the natural assets of the site itself.

I will explain using a fascinating frontier of scientific research, comparative phylogeography, which illuminates the origins of marine and terrestrial biodiversity. Ecology, genetics, and evolution come together in comparative phylogenetic analyses that are helping to reveal some of the nature’s most intriguing histories and to discover otherwise unrecognized cradles of biological diversity that can be highly important in conservation efforts. John Avise, the founder of phylogeography (Avise 1987), calls for a carefully designed network of Phylogeographic Sanctuaries on each continent and in each marine region that could be promoted and distinguished in a similar fashion as historical landmarks honoring important events in human affairs (Avise 2008).

In the marine realm, phylogeography affirms that tropical oceans are characterized by biodiversity hotspots (including the Caribbean and the “Coral Triangle”—a mega-biodiverse marine habitat that stretches between the Philippines, Indonesia, and New Guinea) and endemism hotspots (pockets packed with species that are limited only to a restricted region, such as Hawaii and the Red Sea). Biodiversity hotspots have been widely recognized as evolutionary incubators producing new species. As Bowen et al. (2016) disclose, new research data are emerging that show that both biodiversity hotspots and endemism hotspots are important in producing novel evolutionary lineages and may work together to enhance biodiversity on the ocean planet.

The phylogeography of coral reef diversity, i.e., of the pattern of species richness on coral reefs, is of a particular relevance, since it represents a fundamental pre-condition for informed decisions regarding the conservation and management of these globally threatened and declining hotbeds of biodiversity. Notable contributions in this area (Reaka et al. 2008; Reaka and Lombardi 2011) are unmasking an intricate mosaic of cradles of species richness and of dispersal routes that draw affinities among variously distant ocean regions and archipelagos. Understanding the dynamics of speciation and extinction across these ancient gateways—with their legacy biotas as well as their newly sprouted species—by using recently available genetic techniques is, according to Reaka (2014), one of the greatest challenges and opportunities of the twenty-first century.

These global analyses, which are yielding insights unavailable from any one location, are also hard to match in their potential to fuel dazzling experiences and truly transnational legacies. They harbor immense promise to keep pushing the boundaries of visionary, cutting-edge science through geographically unrestrained inspiration. I share an outline of a “Reefs to Rainforests” globe-circling project envisioned by Avise and to be guided by his foresight under the auspices of Pangea World:

“Coral reefs and tropical rainforests are two of our planet’s richest biotic environments, yet exactly how they acquired and maintain their exceptional biodiversity remains mostly conjectural. In only a few stunning locations on planet Earth do these two habitats co-exist in close proximity. Such evocatively adjoined sites are valuable for many reasons. From a scientific perspective, they can be studied jointly and in the novel comparative framework of land-versus-sea to address innumerable questions about the ecological and evolutionary wellsprings of organic variety; furthermore, these paired environments offer a dual bounty of species and biological compounds of interest to both the basic and the applied sciences. From a conservation perspective, reefs and rainforests are biodiversity hotspots each clearly worthy of protection and monitoring in its own right, but even more so when the two are adjacent to one another. Finally, from the perspective of the hospitality industry and its clientele, pairs of juxtaposed reefs and rainforests hold a powerful allure that at its base is both esthetic and intellectual.”

A resort that would advocate and support an effort to link these two-habitat jewels into a transnational necklace of knowledge of universal value would not only seize a unique niche and business premium; it would also accelerate science and conservation in a major way.

Pangea World aspires to create “Paths of Wonder” across the globe, as a new platform for exchange and synthesis of scientific knowledge and for the development of intellectual delights that would become signatures of transnational resorts and of their capacity to treat their guests to unique insights into distant elements in the various global ecosystem networks, enhancing their awareness of planetary processes and the need to think globally in our future planning. The experience—live, uniquely meaningful, and uniquely immune to imitation by being offered from a vantage point inside a vast labyrinth of wonder—will be profoundly different from experiences gained in a museum. Moreover, there are no limits on the spatial expansion of this labyrinth. It can amount to millions of acres, is inherently very selective in the choice of land and marine habitats a transnational resort will “borrow” from different corners of the world, and is executed in an environmentally enlightened fashion that leaves no physical imprint. The larger and more ambitious the project becomes, the higher the scientific and conservation values of its natural stock and the grander its capacity to reward its patrons with unparalleled stimulation of the mind and systematically to upgrade the complexity, interest, and educational value of these intellectual treats through access to ongoing discoveries. While the extent of the project’s expansion will vary based on the investor’s ambition, it is safe to assert that the cost of such a dramatic amplification of the project’s boundaries through science-fuelled experience management will be a fraction of that which would be needed for an actual purchase of those assets, most of which, moreover, can never be bought.

This business strategy generates robust incentives for investments—not donations—into research, training, and conservation-tailored employment across vast land and marine habitats that are currently marginalized economically but possess untapped economic worth in the knowledge they contain. It lets the path of the project’s “contextual” expansion transcend strings of knowledge-rich natural sites demanding strict protection and, hence, prime candidates for transformation into research hubs whose integrity and economic security will be ensured by their wonder harvests’ central role in the project’s business plan. This creates “benefit zones” that dwarf—in scale and capacity for sustainable development—the existing approaches to linking business strategies with destinations’ conservation priorities.

Bringing science—and, through science, conservation—into the heart of a business model in which quality, competitiveness, and prestige grow along with the geographical footprint of the underwritten research is the core premise of a resort project’s rise to a transnational resort.

It is most meaningful to me that some of the initial endorsements of the concept that defines the transnational resort opportunity appeared in both hospitality and science publications. In an editorial in Hotels, Weinstein (2006) commends my endeavor to “inspire a new generation of luxury resorts as spas for the mind and as gateways into journeys of wonder that string and guard heritage marvels along the frontiers of scientific exploration” (p. 7). Writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Avise (2008) lends support to my ambition to value this new resort model as a catalyst of “a global archipelago of interconnected ‘wonder sites’ where the scientific study and preservation of nature are the explicit and formal motivation for linking sustainable economics with science” (p. 11567). Basic science endeavors of transnational and global ambition stand to gain the most.

Prominence Through Defiance of the Private Enterprise Economics of Basic Research

Koppelman et al. (2010) use the angle of science diplomacy to point out that international spaces outside of national jurisdictions—including Antarctica, the high seas, the deep sea, and outer space—will require entirely new approaches to international cooperation, informed by scientific evidence. Echoing this priority are discussions that are unfolding at the United Nations and across countries throughout the world on the subject of the urgent need to craft agreements to protect biodiversity in the high seas (Fox 2019). These international waters (i.e., waters farther than 200 nautical miles from shore) are attracting growing interest from researchers and companies searching for valuable marine genetic resources. As a result, international negotiations are intensifying in an effort to bridge two opposing views: declaring these resources the “common heritage of mankind” or leaving them free-for-all, patentable by anyone under the principle of the “freedom of the high seas” (Kintisch 2018). In their editorial in the recent issue of the International Social Science Journal, dedicated in its entirety to “Ocean Frontiers,” Havice and Zalik (2018) note that these unfolding processes and the projects aimed at governing the ocean and ocean resources stand to reshape human use and relationship with the oceans for generations to come.

As with the high seas, the transnational reservoir of knowledge and wonder contained in the threads of the earth’s evolutionary and ecological fabric is beyond national jurisdictions. Yet, it is precisely at this transnational level where the most exceptional opportunities exist for hospitality and science to meet and induce new industry standards for outstanding performance that stimulates knowledge, benefits the environment, and sets a new measure of exclusivity and purpose in world travel.

To further explain, I point out that humanity’s long-term security, prosperity, and health are critically dependent on a form of infrastructure that, regrettably, is undervalued and underfunded across the world: the infrastructure of fundamental science. Basic scientific research is largely dependent on government funding, and this dependence represents a major hindrance to the ambition and execution of research visions, particularly in basic science projects that transcend national borders.

Reif (2016) writes in The Wall Street Journal: “the qualities that make industry good at applied research and development—an appetite for immediate commercialization, a laser focus on consumer demand, an obligation to maximize short-term returns, and a proprietary attitude about information—make industry a bad fit for supporting basic scientific research” (p. A17). This observation echoes the influential work of Kenneth J. Arrow, a 1972 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences Laureate. While making the case for basic scientific research as the prime source of significant advances in knowledge, Arrow (1962) argued that appreciating and capitalizing on knowledge as a precursor of future knowledge do not align with the operation of private enterprise system and its emphasis on property rights.

As already noted in this article’s introduction, I have challenged the general validity of the conclusion about the incompatibility of “private profit opportunities” and “knowledge as public good” with a disclosure that the international tourism industry, led by the resort enterprise, can deliver a singular exception. I have established that the international resort enterprise is well positioned and economically motivated to defy the free-enterprise economics of basic research and to become the principal business partner with strong business interests vested in driving new, geographically unrestrained scientific discoveries for the purpose of exploiting these discoveries to enrich the rewards of world travel. Such an exploitation, which is primarily an exercise in interpretation, is not conditioned on the ownership of the underwritten scientific knowledge as intellectual property. In other words, the business value of monopoly over the funded basic research findings does not apply in the tourism context (Ayala 2017).

Loose (2013) well summarized the genesis of my position. “She began to wonder what industry could best serve as a conduit to bring these knowledge riches to the world. Which industry would, essentially, be okay with passing on the knowledge, scientific and otherwise, to the world free of charge. More than that, which industry would benefit from passing on that knowledge? And the one she came up with surprised even her: the international resort industry” (p. 17).

The implications are enormous and the transnational resort model seeks to harness them to the fullest. As both experience manager and ecophilanthropist, a transnational resort will capitalize on and shepherd discoveries brought to light through comparisons and correlations among research sites located across multiple countries and their exclusive economic zones. Its operation will, therefore, perfectly align with Pangea World’s principle that while knowledge derived from natural resources in a particular country should be shared with and benefit that country, the knowledge unlocked through cross-national insights into the earth’s natural legacies ought to be treated as a global asset of enormous potential to advance science, medicine, and other fields of value to humanity and to be unhindered in its promise to serve as a womb of future harvests of knowledge.

The Pacific Region offers a superb receptor.

The Pacific: an Economic Powerhouse of Wonder’s Crossroads

“A road map for the South Pacific economy,” which I devised for the UNESCO Office for the Pacific States (Ayala 2000c), explains what ignited my priority focus on the Pacific. I was alarmed to find out that the planning and building of the Pacific Island Nations’ tourism economies had virtually overlooked the daunting diversity and complementarity of natural environments within and across individual countries: a priceless asset that had been suppressed and wasted by the homogenized image of an “island paradise.” I planted an alternative: a development strategy that would interlink, value, and protect the region’s geological formations, archeological legacies, and land and marine ecosystems—many ranking as the biologically most opulent places on earth—as giant databanks that are systematically unlocked through science exploration in concert with developing a regional tourism industry second to none. The resort industry’s potential to shepherd and capitalize on this strategy was front and center. That UNESCO-sponsored study provided the foundations for an endeavor that has expanded far beyond its original South Pacific focus.

Named The Pacific Bridge to Noble Wealth (PBNW), this endeavor was inaugurated at an international conference hosted by the West Coast Headquarters of the National Academies (in Irvine, California) on April 15, 2009, and introduced with the unveiling of a partnership agreement Pangea World formalized with UNESCO Pacific in 2008 (Brennan 2009). As emphasized at that event, the collective scientific importance of the connections and dynamics that distinguish the Pacific Island Region’s spectacularly diverse natural heritage expands further in worth and prominence along affinities that can be drawn all the way to the islands and ecosystems of the Pacific coast of the Americas and, in the opposite direction, along the ocean-linked biological networks of the larger Indo-Pacific Region. For example, extending the Panama Paleontology Project coordinated by STRI and exploring such fundamental issues as the evolution of our planet’s climate and the formation of land and marine ecosystems across the magnificent geological and fossil records of Fiji and other Pacific Island Nations would be of immense promise.

Geography of Wonder as a New Diplomatic Frontier with a Hospitality Flair

An invitation from Sylvia Howard Fuhrman, then Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations, treated the PBNW agenda to further international exposure and endorsements. I gratefully embraced this opportunity to welcome heads of state, diplomats, and high-level UN officials at the United Nations International School (UNIS) in New York on September 19, 2010. The event profiled the PBNW as a pilot map of the economic geography of wonder and as a new approach to diplomacy guided by frontier science. The event’s UN context also provided a most fitting setting for the explanation of the utmost selectivity that will guide the choice of pilot “staging areas” for transnational resort projects. This selectivity pertains to the magnitude of the environmental and social benefit that the staging area—and the investment into the project that will be anchored in that area—will have the capacity to spur along knowledge bridges never before built. Spanning areas enclosed within different political or administrative borders, these bridges will stimulate the project’s signature identity as a tourism-scientific-diplomatic venture that exerts transformative influence in all three sectors that are touched by its distinctive identity.

A transnational resort blueprint that takes this perspective down to earth—and is master-planned to emblematize it—made its debut at the UNIS-hosted event. Intentionally, for the purpose of stressing the importance of conceptual and planning stages, I have not anchored this blueprint in a resort project that already operates or is under development. Rather, I have engaged an undeveloped-property asset of exquisite location, pristine natural condition, and other characteristics desired by a sophisticated resort in order to demonstrate the formidable added value to the seller, buyer, the host country and the host region, and humanity that would be generated if this prime real estate entered the market with exclusivity already sealed by a transnational dimension immune to imitation.

This chosen anchor, a privately owned island portfolio in Las Perlas Archipelago in the Gulf of Panama, is bathed by the Pacific waters in Panama’s coastal zone. It lies outside the borders of the Pacific Island Nations. It does not belong to the cluster of countries represented by the UNESCO Office for the Pacific States. Yet, its geological past and its ecology radiate deep into the Pacific in one direction and tie it with the Centro-American Isthmus and parts of South America in the opposite direction. While located within the political borders of Panama, it is deeply connected through natural forces with the legendary Galápagos Islands, located in the Pacific Ocean about 600 miles west off the coast of South America and politically belonging to Ecuador. These and other border-defying linkages uniquely position this island portfolio to serve as a trailblazer for investments in resort projects of transnational stature and legacy.

A Vantage Master Plan of the Trans-Pacific Resort Opportunity

Following its unveiling at the UNIS-hosted event, this flagship transnational-legacy invitation became the centerpiece of the before mentioned international symposium themed The Economic Epic of Earth Evolution, attended and addressed by prominent scientists, economic experts, and diplomats, and staged at the West Coast Headquarters of the National Academies on February 7, 2014.

Quoting from the University of California, Irvine News Release of February 11, 2014 (UC Irvine 2014): “Michael Clegg, the Donald Bren Professor of Biological Sciences at UC Irvine and foreign secretary of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, underscored the importance of the Pangea World concept as a model for sustainability. ‘In order to improve the quality of human life in the face of increasing demands on our earth’s resources, we must develop scientific approaches to problems of sustainability,’ Clegg said. ‘Pangea World’s vision embodies strategic synergies linking the creation and utilization of scientific knowledge to a business model firmly grounded in legacy investment opportunities’.

The cornerstone of the featured legacy investment opportunity, the island portfolio comprised of Isla Bayoneta, Isla Cañas, and Cañas-adjoining islet Isla La Caida and boasting 50 pristine beaches along more than 19 miles of the islands’ coastlines, would certainly qualify as prime real estate. In a traditional real estate–based approach, the worth of this portfolio would be the sum of the included properties’ values. In terms of their locations at the opposite sides of Las Perlas Archipelago, through this traditional lens, these properties are fragmented units.

Pangea World’s approach and valuation erased this fragmentation. The islands were collectively appraised—through scientific research already performed—as a veritable microcosm of the immense biological, ecological, and geological interest of Las Perlas archipelago of more than 200 islands. Moreover, this research, which involved STRI experts, has disclosed that Bayoneta and Cañas/La Caida Islands:

-

1.

Complement each other in revealing the geological story of the Galápagos Hot Spot, which, 80 million years ago, supplied the oldest “building blocks” of today’s Panama

-

2.

Enrich each other in showcasing the universal value of Las Perlas—just 10 thousand years young, split from Panama’s Pacific Coast by the rising sea level fed by the melting of the world’s glaciers—as an ideal place to witness the earliest stages of the process of evolution

-

3.

Reinforce each other as superb staging areas for interpretation-assisted insights into two mammoth pools of wonder. In one direction, insights into the biodiversity treasure trove of the Eastern Tropical Pacific Seascape that links the Gulf of Panama to the Galápagos Islands and other Pacific islands along the convergence of several major oceanic currents. In the other direction, insights into the islands’ ancestral land of the Isthmus, now boasting the Darién National Park—a UNESCO World Heritage site whose natural capital and knowledge content are intertwined with those of the Chocó-Darién Global Ecoregion that runs along the Pacific coast of eastern Panama, western Colombia, and northwestern Ecuador.

A strict focus on Bayoneta and Cañas Islands’ territories and their immediate surroundings would ignore the immense added value of their role in a monumental ecosystem complex, the richness of their geological connectivity with other parts of the Pacific, and the intricate relationships of these islands—as former mainland mountains—with continental flora and fauna, with all their potentials in terms of competitive and comparative advantages. Already in possession of this added value, this island portfolio boasts an enhanced spatial dimension, authenticated by world-class science, not conditioned on purchasing any additional real estate, and central to endowing the islands’ future facilities with the capacity to pursue unprecedented ecophilanthropic aspirations, without sacrificing the traditional pleasures of present-day luxury resorts and private retreats. Moreover, as a portal into the scientific exploration of the PBNW’s wonder paths that transcend international boundaries, this island portfolio is positioned to blaze a trail for the sustainable future of an entire region. This privileged position has already gained the support of heads of state in the region, as reflected in the following statement: “Pangea World’s strategy of interlinking and valuing multiple pools of knowledge-rich natural capital with a legacy investment in the Panama islands can provide a new economic geography for the future benefit of our people,” said Winston Thompson, Fiji’s ambassador to the United States. “We remain strongly committed to this vision” (UC Irvine 2014).

In its economic aspiration, this vision entails a most symbolic affinity with the Panama Canal. The Canal is an engineering marvel of unparalleled role in the movement and connectivity of world commerce. The PBNW is being laid out as a multi-channel canal for a transnational knowledge economy shaped by tectonic activity, evolution, and other forces that molded the veins of the knowledge mineral. By virtue of its anchorage in the naturally opulent Gulf of Panama that cushions the very Pacific entry to the Panama Canal, the Bayoneta-Cañas legacy property is guaranteed a singular niche in this canal of opportunities for the twenty-first century economy.

And there is another exceptional location along PBNW, which stands out for its capacity—strongly defined by its current ownership—to become an iconic crossroads of the earth’s natural wealth and knowledge-propelled economy and to share both the stewardship and prestige of that accomplishment with the already present luxury hotel partner. That location is Lanai.

What Lanai Could Be

The media coverage that has greeted the recent purchase of 98% of the 140 square-mile Lanai by Larry Ellison, co-founder of the information technology giant Oracle, has rightly and deservingly focused on the bold, most timely green vision that this transaction has brought to Hawaii’s sixth largest island. Mooallem (2014) points out that Ellison was drawn to the island by the potential of a great accomplishment, to be shaped by his vision of a premier tourist destination that doubles in value and prominence as “the first economically viable, 100% green community.” Ellison has set to turn Lanai into an environmental laboratory featuring solar power, electric cars, and organic farms and converting sea water to fresh water (Allen 2012) and, in the process, to create a world-class model of sustainability on the island (Werner 2014). A wellness company aimed at giving people solutions for more healthy living is now integral to this grand, sustainable society-building vision (Brodwin 2018). And so are luxury tourism pillars of the highest caliber. The Four Seasons Resort Lanai (originally Manele Bay), one of the two Four Seasons properties that Ellison acquired with the purchase, has already reopened after a profound transformation, with accolades that include its praise as the best Four Seasons resort in the world (Runnette 2016).

Indeed, Lanai has the potential to become the place of a great accomplishment. The ambition that is shaping this accomplishment is visionary and praiseworthy. Yet, I will suggest that this ambition does not do justice to the magnitude of the accomplishment that the Lanai-Ellison marriage could yield.

Oracle offers a reference of relevance. The corporation is a prominent “architect” of connectivity in the world increasingly shaped by information technologies, skills, and processes. Its footprint is global, on two fronts. Oracle continues to revolutionize how data is managed in today’s global, digital economy. At the same time, through Oracle Academy and other vehicles of social responsibility, the corporation continues to support millions of students worldwide, as an investment in the future of the evermore technology-driven global economy.

The purchase of Lanai has given Ellison an extraordinary springboard for making a complementary, but no less impactful, investment in the future of the natural capital for the knowledge economy and for doing so in a business-savvy fashion. The implementation is conditioned on the recognition and appreciation of Lanai’s strategic position within a broader and very prominent context. I will mention just three dimensions of this prominence.

The Hawaiian Archipelago, to which Lanai belongs, has been compared to the Galápagos Islands. These comparisons, premised on evolutionary vigor, favor Hawaii. For example, adaptive radiation—showcased by the Galápagos finches and constituting a centerpiece of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution—was even more prolific when it took place in Hawaii (Wylie 2015). The much deserved acclaim as an iconic laboratory of evolution that surpasses the Galápagos in the creative power of natural selection has not yet accrued to Hawaii outside academia.

The immense evolutionary importance of the Hawaiian Archipelago has and will continue to nurture scientific breakthroughs of global significance. The latest discoveries that Hawaii, a hotspot of ancient “legacy” species, is experiencing further evolutionary radiation and, thus, acts as an exporter of novel biodiversity in the tropical ocean realm (Bowen et al. 2016) are compounding this awesome reserve of wonder waiting to be revealed and guarded.

The World Heritage listed Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, a joint legacy of the former Presidents George W. Bush and Barrack Obama, is the largest contiguous, fully protected conservation area under the US flag. Its half-million-square-mile span of ocean, anchored by the uninhabited northwestern islands of Hawaii, is a giant sanctuary for endangered species and the home of some the world’s northernmost and healthiest coral reefs (Barnett 2016). While within the US exclusive economic zone, the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument belongs to all of humanity by virtue of its World Heritage status.

Viewed through the eye of Pangea World, first from the angle of natural assets, Lanai is a superb staging area whose singularity is not defined by what it possesses within its borders but, rather, by its treasure trove context. And this singularity, revisited from the angle of the exclusivity of Lanai’s hospitality offer and its clients’ profile, uniquely invites a strategy that would mobilize major business and legacy rewards by harnessing a huge performance-reserve from beyond the island’s borders.

Pioneering a hospitality offer that acquires a universal value by underwriting and extolling a lavish supply of wonder of universal value without intruding into that wonder would be most synergistic with the “great accomplishment” goal Ellison has set for Lanai. “Living” exhibits that would evolve in content with an ongoing input of science-mined, interpretation-tamed wonder, and which would serve as gateways into virtual excursions from Hawaii across other evolutionary hotspots of the Indo-Pacific and the world, would not be offered in a capsule of the natural museum in New York, London, or other contextually anonymous place. They would be savored live, within contextually genuine qualities of light, sound, aroma, and other sensory experiences. And they would profoundly enrich the core theme of Lanai’s positioning to travelers, which, as Seligson (2017) observes, is that it is a less “bottled paradise” version of Hawaii, geared towards open-minded and adventurous jet-setters who want privacy, exclusivity, and a bit of glamor.

On the tourism front, Seligson (2017) writes, “he [Ellison] wants to bring Lanai onto the ultra-high-end travel circuit—to put this remote stretch of volcanic rock on the St. Bart’s, Aspen, Courchevel, Hamptons, and Nantucket circuit.” No doubt, Ellison’s bold green vision for Lanai, infused with Four Seasons’ pampering, will easily insert Lanai into that circuit. But, simultaneously, Lanai could excel as a “summit” location and operation of an ultra-high-end circuit of wonder whose hospitality hosts would become major players on the world stage by revealing and protecting linked chains of ecological and evolutionary wonders across the planet. It would superbly complement the Bayoneta-Cañas island portfolio in charting the Panama Canal analogy for the twenty-first century knowledge economy.

Epilogue

Pangea World’s mission and aspiration are now enriched with a most meaningful association with Villa Tugendhat, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s architectural masterpiece and a UNESCO World Heritage treasure. An international press conference and signing act held on Villa Tugendhat’s premises in the Czech city of Brno on June 15, 2017, formally interlinked Pangea World’s endeavor to harness the free-flowing natural reservoirs of knowledge to benefit humanity and the spirit of the Villa, where the celebrated architecture and design by Mies van der Rohe revolutionized human relationship with the environment via masterful execution of free-flowing space.

In the words of Federico Mayor, as presented at the event: “It is deeply meaningful to me, as UNESCO’s former Director General, that Villa Tugendhat, an icon of UNESCO’s World Heritage mission, will become an icon of Pangea World’s global mission that values knowledge as the economic safeguard of the earth’s heritage.”

A global scale is the only scale with which to fully disclose, consolidate, value, and protect the free-flowing natural reserves of the knowledge stock, within a multiplicity of overlaying units delimited by geological, evolutionary, and ecological markers.

That is where the transnational resort model steps up to deliver new-generation resorts as masters of a high-value engagement of the elusive geography of wonder and as invitations to “global-citizen” investors and travelers of the means and motivation to achieve and pass on world-changing legacies. This market focus is pragmatic, subordinated to the emphasis on projects capable of contributions whose magnitude will draw international attention and seed inspiration across the world.

It has been my goal, since my earliest articles in peer-reviewed tourism and hospitality journals, to use the business incentive of setting new standards of excellence in experience management to build the intellectual, strategic, and operational frameworks for awakening the resorts’ dormant capacity to employ science-mediated revelation of wonder in a manner that generates economic energy, facilitates new scientific breakthroughs, creates novel employment opportunities in resource conservation, and portrays investments in knowledge-weighted appreciation of natural capital as emblems of business stewardship.

The transnational resort is a culmination of this journey. It lays the foundations for a new model of hotel portfolio, shaped by evolutionary, ecological, and other vital links among the natural knowledge banks and, thus, acquiring a global transformative capacity for linking science, conservation, and economic development in a manner that has never been attempted before. It heralds my position that the fast-progressing transformation of the global economy into a knowledge-based economy offers a unique momentum for activating the collective potential of the international resort enterprise to become the most powerful force to shape the world’s journey towards sustainability. Making that happen is the ultimate aspiration of my professional and also deeply personal mission.

References

Aguilar, E., & Saied, A. (2004). Cuando la conservación paga. Martes Financiero (Panama), 325(May 25), 8–10.

Allen, N. (2012). Oracle CEO Larry Ellison planning green experiment on Hawaiian island. The Telegraph (October 3). https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/environment/9583393/Oracle-CEO-Larry-Ellison-planning-green-experiment-on-Hawaiian-island.html.

Arrow, K. J. (1962). Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for invention. In Universities—National Bureau Committee for Economic Research and Committee on Economic Growth of the Social Science Research Council, The rate and direction of inventive activity: Economic and social factors (pp. 609–626). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Avise, J. C. (1987). Intraspecific phylogeography: the mitochondrial DNA bridge between population genetics and systematics. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 18(1), 489–522.

Avise, J. C. (2008). Three ambitious (and rather unorthodox) assignments for the field of biodiversity genetics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(Suppl. 1), 11564–11570.

Ayala, H. (1991a). International hotel ventures: back to the future. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 31(4), 38–45.

Ayala, H. (1991b). Resort landscape systems: a design management solution. Tourism Management, 12(4), 280–290.

Ayala, H. (1995a). Ecoresort: a ‘green’ masterplan for the international resort industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 14(3-4), 351–374.

Ayala, H. (1995b). The international resort industry, heritage conservation and sustainable development: towards an unprecedented partnership. Insula—International Journal of Island Affairs, 4, 32–47.

Ayala, H. (1995c). From quality product to ecoproduct: Will Fiji set a precedent? Tourism Management, 16(1), 39–47.

Ayala, H. (1996a). Resort ecotourism: a master plan for experience management. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 37(5), 54–61.

Ayala, H. (1996b). Resort ecotourism: a paradigm for the 21st century. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 37(5), 46–53.

Ayala, H. (1997). Resort ecotourism: a catalyst for national and regional partnerships. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 38(4), 34–45.

Ayala, H. (1998). Panama’s ecotourism-plus initiative: the challenge of making history. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 39(5), 68–79.

Ayala, H. (1999). A bridge to the millennium: the ideal and the promise of a heritage-driven economy. In M. S. Ratchford (Ed.), TCR strategic alliance: Tourism-Conservation-Research (pp. 13–20). Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Ayala, H. (2000a). Panama’s TCR action plan: building alliances for a heritage-driven economy. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 41(1), 108–119.

Ayala, H. (2000b). Surprising partners: hotel firms and scientists working together to enhance tourism. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 41(3), 42–57.

Ayala, H. (2000c). Vaka Moana—a road map for the South Pacific economy. In A. Hooper (Ed.), Culture and sustainable development in the Pacific (pp. 190-206). Asia Pacific Press.

Ayala, H. (2003). The art and power of welding science and heritage in a knowledge economy for the 21st century. In M. Konečný (Ed.), Digital Earth: information resources for global sustainability. Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Digital Earth (pp. 105–106). Brno: Masaryk University.

Ayala, H. (2004a). A strategic leadership vision for Panama – an original strategy. Business Panama, 25(5), 18–21.

Ayala, H. (2004b). Strategic synergies: Panama to showcase a new trade and investment paradigm for the world’s knowledge economy. Business Panama, 25(8), 8–12.

Ayala, H. (2017). The economic might of earth’s evolution: the epic promise of knowledge. SAGE Open (April-June), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017701975.

Ayers, T. (1999). Panama applies science to tourism and conservation efforts. Science, 284(5419), 1546–1547.

Barnett, C. (2016). Hawaii is now home to an ocean reserve twice the size of Texas. National Geographic (August 26). http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/08/obama-creates-world-s-largest-park-off-hawaii/#close.

Bowen, B. W., Gaither, M. R., DiBattista, J. D., Iacchei, M., Andrews, K. R., Grant, W. S., Toonen, R. J., & Briggs, J. C. (2016). Comparative phylogeography of the ocean planet. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(29), 7962–7969. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602404113.

Brennan, P. (2009). Ecological riches, economic engines: linking tourism and science. The Orange County Register (May 11). http://greenoc.freedomblogging.com/2009/05/11/ecological-riches-economic-engines-linking-tourism-and-science/7075/.

Brodwin, E. (2018). Billionaire Larry Ellison is teaming up with Steve Job’s former doctor to launch a mysterious wellness company on this private island. Business Insider (March 22). https://www.businessinsider.com/larry-ellison-new-wellness-company-food-hawaiian-island-2018-3.

Chan, M. J. (2015). Raja Ampat: the world’s most beautiful islands. Condé Nast Traveller (July). http://www.cntraveller.com/article/raja-ampat-islands-indonesia.

D’Arcy, D. (1999). Panama 2000. Condé Nast Traveller (December), 106-115.

Doctrow, B. (2016). QnAs with Partha Dasgupta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(22), 6090–6091.

Doerr, A. (2011). Send in the clouds. The New York Times Style Magazine (November 20), 136-141.

Dunford, J. (2007). Where Peru’s wild things are. The Guardian (December 30). http://www.theguardian.com/travel/2007/dec/30/peru.green.

Endara, M. (1998). Taking conservation of Panama’s natural resources into the twenty-first century. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 39(5), 73.

Fox, A. (2019). Mapping efforts envision vast ocean reserves. Science, 364(6435), 15.

Hart, S. (1999). Birdman of Panama. Architecture (April), 136-140.

Havice, E., & Zalik, A. (2018). Editorial: ocean frontiers, epistemologies, jurisdictions, commodifications. International Social Science Journal, 68(229-230), 219–235.

Havice, E., Campbell, L. M., & Braun, A. (2018). Science, scale and the frontier of governing mobile marine species. International Social Science Journal, 68(229-230), 273–289.

Hogrefe, J. (1999/2000). Panama on its own. Civilization (December/January), 50-55.

Kintisch, E. (2018). U.N. tackles gene prospecting on the high seas. Science, 361(6406), 956–957.

Koppelman, B., Day, N., Davison, N., Elliott, T., & Wilsdon, J. (2010). New frontiers in science diplomacy: navigating the changing balance of power. London: The Royal Society.

Lempinen, E. W. (2006). Ayalas’ passion for knowledge shines at AAAS event. Science, 312(5773), 542.

Lew, L. Y. (2007). Pangea World: combining tourism, science and environmental education. IOSTE (International Organization for Science and Technology Education) Newsletter, 10(1), 6–8.

Loose, T. (2013). Paradise with a purpose. OC Register Magazine (October 28), pp. 14-18.

Miller, G. (1999). Panama in transition. Hotels, 33(3), 44.

Mooallem, J. (2014). Kingdom come. The New York Times Magazine (September 28), pp. 22-29, 58-59.

Murphy, J. (2016). Inside Leonardo DiCaprio’s eco-resort and 8 more retreats where you can help protect the ocean. Vogue (November 14). http://www.vogue.com/article/luxury-island-resorts-that-protect-the-ocean.

Nelson, R.R. (1959). The simple economics of basic scientific research. The Journal of Political Economy, 67, 297–306.

Nemecek, S. (1999). A plan for Panama. Scientific American, 281, 26.

Nicholson, R. (1999). Keynote speech. In M. S. Ratchford (Ed.), TCR strategic alliance: tourism-conservation-research (pp. 21–24). Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Reaka, M. L. (2014). Out of Eden: tracing the patterns of global endemism and diversity. Paper presented at the Pangea World conference, The economic epic of earth’s evolution: the new geography, diplomacy, and legacy for the knowledge economy—from California to the world. Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Irvine, CA (February 7).

Reaka, M. L., & Lombardi, S. A. (2011). Hotspots on global coral reefs. In F. E. Zachos & J. C. Habel (Eds.), Biodiversity hotspots (pp. 471–501). Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Reaka, M. L., Rodgers, P. J., & Kudla, A. U. (2008). Patterns of biodiversity and endemism on Indo-West Pacific coral reefs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(Suppl. 1), 11474–11481.

Reif, L. R. (2016). The dividends of funding basic science. The Wall Street Journal, (December 6), A17.

Rubinoff, I. (1998). Science and ecotourism on the Isthmus of Panama. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 39(5), 78.

Runnette, C. (2016). Larry Ellison’s private Eden is open for business. Bloomberg (April 13). https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2016-04-13/four-seasons-manele-bay-lanai-hawaii.

Rush, G. (2005). Into the Peruvian wild. Departures (March/April), 143–148.

Sánchez, C. (1998). Tourism as a tool for knowledge and conservation of natural capital. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 39(5), 76.

Satow, J. (2015). An idea hits the beach. The New York Times/Sunday Business (April 5), 10.

Scheffer, M., & van Nes, E. H. (2018). Seeing a global web of connected systems. Science, 362(6421), 1357.

Secretaría General de Turismo (1986). From Parador to Parador Spain. Barcelona and Madrid: Luna Wennberg Editores.

Seligson, H. (2017). Larry Ellison wants Lanai to be the most incredible resort in the world. Town and Country (April 7). https://www.townandcountrymag.com/leisure/travel-guide/a9201006/larry-ellison-four-seasons-lanai/.

Tribaldos, C. (1998). Tourism champions conservation of a world crossroads’ heritage. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 39(5), 71.