Abstract

Prasugrel is a third-generation thienopyridine that achieves potent platelet inhibition with less pharmacological variability than other thienopyridines. However, clinical experience suggests that prasugrel may be associated with a higher risk of de novo and recurrent bleeding events compared with clopidogrel in Japanese patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). In this review, we evaluate the risk of bleeding in Japanese patients treated with prasugrel at the doses (loading/maintenance doses: 20/3.75 mg) adjusted for Japanese patients, evaluate the risk factors for bleeding in Japanese patients, and examine whether patients with a bleeding event are at increased risk of recurrent bleeding. This review covers published data and new analyses of the PRASFIT (PRASugrel compared with clopidogrel For Japanese patIenTs) trials of patients undergoing PCI for acute coronary syndrome or elective reasons. The bleeding risk with prasugrel was similar to that observed with the standard dose of clopidogrel (300/75 mg), including when bleeding events were re-classified using the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium criteria. The pharmacodynamics of prasugrel was not associated with the risk of bleeding events. The main risk factors for bleeding events were female sex, low body weight, advanced age, and presence of diabetes mellitus. Use of a radial puncture site was associated with a lower risk of bleeding during PCI than a femoral puncture site. Finally, the frequency and severity of recurrent bleeding events during continued treatment were similar between prasugrel and clopidogrel. In summary, this review provides important insights into the risk and types of bleeding events in prasugrel-treated patients.

Trial registration numbers: JapicCTI-101339 and JapicCTI-111550.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is highly prevalent and is associated with an increased mortality rate in Asian countries, except in Japan, where the age-adjusted mortality rate in patients with CAD is lower than that in Western countries [1, 2].

Clinical guidelines for the management of patients with myocardial infarction (MI) advocate the co-administration of aspirin and a thienopyridine antiplatelet drug to reduce the risk of re-infarction and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [3, 4].

Clopidogrel is one of the most widely used drugs in this setting. As a prodrug, clopidogrel must undergo metabolism to its active form via members of the cytochrome P450 system, especially the isoform CYP2C19. However, this introduces some limitations, particularly regarding altered metabolism and reduced efficacy in patients with CYP2C19 polymorphisms or during co-administration with drugs that might block CYP2C19 activity. Clopidogrel is unlikely to be adequately effective in patients with poor platelet inhibition or polymorphisms associated with poor metabolism of clopidogrel, increasing the risk of subsequent cardiovascular events [5]. For these reasons, there is increasing reliance on pharmacogenomic testing to detect alleles associated with reduced or poor metabolism of clopidogrel. In addition, point-of-care assays are increasingly being used to monitor platelet activity.

Prasugrel is a third-generation thienopyridine that irreversibly inhibits platelet P2Y12 receptors. It is also a prodrug that is predominantly metabolized by CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 [6, 7]. Based on these properties, the pharmacology of prasugrel is less susceptible to CYP2C19 polymorphisms [8]. Therefore, it achieves potent platelet inhibition and is associated with less pharmacological variability than other thienopyridines. Nevertheless, some intrinsic and extrinsic factors may influence the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prasugrel, including body weight and age [9].

Several randomized controlled studies have compared the efficacy and safety of prasugrel and clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI for elective reasons or for acute coronary syndrome (ACS). These studies include TRITON-TIMI 38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38) [10], PRASFIT-ACS (PRASugrel compared with clopidogrel For Japanese patIenTs with ACS undergoing PCI) [11], and PRASFIT-Elective (PRASugrel compared with clopidogrel For Japanese patIenTs undergoing Elective PCI) [12].

The objectives of this review are to summarize the results of the recent PRASFIT studies, by comparing them with those of the TRITON–TIMI 38 study. We focus on the efficacy of both drugs and potential safety concerns identified in these studies. As described later in this review, some types of bleeding events were more frequent in prasugrel-treated patients in the PRASFIT studies. Therefore, we also examine the results of additional analyses of the PRASFIT studies aimed at elucidating the potential risk factors for bleeding and the possible opportunities to reduce the risk of bleeding.

Designs of the PRASFIT studies

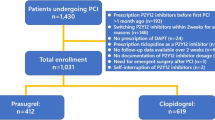

The designs of PRASFIT-ACS and PRASFIT-Elective, including the eligible patients and treatments received, are described in more detail in the original reports.

Briefly, PRASFIT-ACS [11] enrolled patients who satisfied all of the following criteria and were scheduled for coronary artery stenting: males/females aged ≥20 years; presence of chest discomfort or ischemic symptoms lasting ≥10 min within 72 h before randomization; ST-segment deviation ≥1 mm, or T-wave inversion ≥3 mm, or elevated levels of cardiac biomarkers for necrosis.

PRASFIT-Elective [12] enrolled patients aged ≥20 years who were scheduled for elective PCI to treat CAD such as stable angina or prior MI confirmed on coronary computed tomography.

Patients in both studies were randomized in a double-blind manner to receive either prasugrel or clopidogrel for 24–48 weeks, depending on the package insert for the stent being used. The loading/maintenance doses (LD/MD) were 20/3.75 mg for prasugrel and 300/75 mg for clopidogrel in both studies.

The primary endpoint in both studies was the incidence of MACE at 24 weeks. Bleeding events were evaluated as safety events, and five categories of bleeding events were defined: (1) non-coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)-related thrombolysis in (TI)MI major bleeding (major bleeding): intracranial or clinically significant bleeding with a decrease in hemoglobin of ≥5 g/dl; (2) non-CABG-related TIMI minor bleeding (minor bleeding): clinically significant bleeding with a decrease in hemoglobin ranging between 3 and <5 g/dl; (3) clinically relevant non-major or minor bleeding: bleeding from critical sites (e.g., retroperitoneal, intrapericardial, intravitreous/retinal, intraspinal, and intra-articular hemorrhage); gastrointestinal bleeding accompanied by decreased hemoglobin; gross hematuria not attributed to external factors; epistaxis requiring otolaryngology; gingival bleeding requiring dental treatment; bleeding requiring discontinuation of the study treatment at the investigator’s discretion; these bleeding events were accompanied by a decrease in hemoglobin of <3 g/dl; (4) other bleeding: bleeding events not satisfying criteria (1–3); and (5) life-threatening bleeding: a composite of fatal bleeding, bleeding requiring intravenous inotropic medication, and bleeding requiring the transfusion of ≥4 units of red blood cells. Bleeding events were recorded for up to 2 weeks after the last dose of the study drug.

Rationale for the prasugrel dose in the PRASFIT studies

In TRITON–TIMI 38, the LD/MD of prasugrel and clopidogrel were 60/10 and 300/75 mg, respectively. In both PRASFIT studies, the LD/MD of prasugrel were 20/3.75 mg, while those of the clopidogrel regimen were 300/75 mg, as used in TRITON–TIMI 38. The lower dose of prasugrel was chosen based on the results of a Japanese Phase II trial [13]. Patients were stratified according to their age and body weight into a standard-risk group (age <75 years and boy weight >50 kg) or a high-risk group (age ≥75 years and/or body weight ≤50 kg). Patients in the standard-risk group were randomized to prasugrel with a MD of either 3.75 or 5 mg, or 75 mg of clopidogrel. Patients in the high-risk group were randomized to receive prasugrel with a MD of either 2.5 or 3.75 mg, or 75 mg of clopidogrel. The LDs of prasugrel and clopidogrel were 20 mg (standard and high-risk groups) and 300 mg, respectively. The study showed that the rates of TIMI major and minor bleeding were similar among the three treatments in both the standard-risk and high-risk groups, and that the level of platelet inhibition was sufficient in both prasugrel arms of the standard-risk group and in the 20/3.75 mg arm in the high-risk group. These results indicate that the lower MD of prasugrel is sufficient in terms of antiplatelet effects in both the standard- and high-risk groups, supporting the use of a lower MD in Japanese patients than in Western patients.

Efficacy of prasugrel and clopidogrel in the TRITON-TIMI 38 and PRASFIT studies

TRITON-TIMI 38 in patients with ACS showed that prasugrel at a LD of 60 mg and MD of 10 mg was associated with a lower risk of the primary endpoint (death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke) than clopidogrel (LD/MD: 300/75 mg) [9.9 vs. 12.1%; hazard ratio (HR) 0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.73–0.90, P < 0.001] [10].

In the PRASFIT-ACS and PRASFIT-Elective studies, Japanese patients were randomized to either prasugrel or clopidogrel. The prasugrel dosing regimen was adjusted to a LD/MD of 20/3.75 mg considering the lower body weight of Japanese patients, but the clopidogrel regimen was the same as in TRITON–TIMI 38 (i.e., 300/75 mg). Both drugs were administered in combination with aspirin (81–300 mg for the first dose and 81–100 mg/day thereafter) for 24–48 weeks. The lower dose of prasugrel was chosen based on the results of a Japanese Phase II trial [13]. The primary endpoint was the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal ischemic stroke) at 24 weeks.

In PRASFIT-ACS, the incidence of MACE was slightly, although not significantly, lower in the prasugrel group than in the clopidogrel group (9.4 vs. 11.8%; HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.56–1.07). In PRASFIT-Elective, the incidence of MACE was 4.1 and 6.7% in the prasugrel and clopidogrel groups, respectively. P values were not calculated in PRASFIT-Elective for two reasons: (1) the study did not have a statistically adequate sample size, even though an extremely low incidence of events was predicted, and (2) clopidogrel was not indicated for patients with stable CAD undergoing PCI in any country at the time this study was planned and started. This means that, at the time of the study, both clopidogrel and prasugrel were being used in an experimental setting in PRASFIT-Elective, and the clinical efficacy and safety of both drugs in this setting were unknown. Therefore, P values were unlikely to be clinically meaningful.

A large registry of 23,994 clopidogrel-treated patients (18,029 ACS and 5965 non-ACS patients) and 2761 prasugrel-treated patients (2132 ACS and 619 non-ACS) has also been published [14]. The results of this registry revealed that the mortality rate was lower in the prasugrel group than in the clopidogrel group among ACS patients, but not in non-ACS patients. These results were consistent with those of randomized controlled trials.

Although prasugrel was associated with lower rates of the primary endpoints in TRITON-TIMI 38, it was associated with an increased risk of bleeding compared with clopidogrel. In a large registry of Swedish patients undergoing PCI [14], although the Mehran risk scores for bleeding were higher in prasugrel-treated patients than in clopidogrel-treated patients, the incidence of in-hospital bleeding was lower in prasugrel-treated patients. In the Japanese PRASFIT studies, prasugrel was associated with a low incidence of MACE and with a low risk of clinically serious bleeding. However, because the incidence of other bleeding (all bleeding other than major bleeding, minor bleeding, or clinically relevant non-major or minor bleeding events) was higher with prasugrel than with clopidogrel, physicians have become concerned that prasugrel may be associated with a higher risk of de novo and recurrent bleeding events compared with clopidogrel. To better understand the risk and characteristics of bleeding events during antiplatelet therapy in Japanese patients with CAD undergoing PCI, it is necessary to review the bleeding events related to both clopidogrel and prasugrel. Although some studies have provided insight into these issues in non-Japanese patients [14,15,16,17,18,19], these findings are not necessarily generalizable to Japanese patients. From this context, in the next parts of this review, we evaluate the risk of bleeding in Japanese patients treated with prasugrel based on the data published to date, and examine whether Japanese patients with a bleeding event are at increased risk of recurrent TIMI major and minor bleeding. This information is important because in routine clinical practice, the attending clinician may be concerned about a higher risk of bleeding in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy who had previously experienced bleeding.

Risk of bleeding in the PRASFIT studies

The incidence of non-CABG-related bleeding events in the PRASFIT studies is shown in Table 1. In PRASFIT-ACS (Table 1), the incidences of most types of non-CABG-related bleeding events were comparable in both groups, especially TIMI major bleeding, the composite of TIMI major and minor bleeding and clinically important bleeding, and bleeding events leading to discontinuation. Intriguingly, the majority of bleeding events in PRASFIT-ACS occurred within about 30 days of PCI (Fig. 1) [20]. In PRASFIT-Elective, the incidences of all types of non-CABG-related bleeding events were comparable in both groups (Table 1).

Reprinted from [23]

Kaplan–Meier analysis of the cumulative incidence of type 3 or type 5 bleeding events in patients in PRASFIT-ACS (a) and PRASFIT-Elective (b).

Considering that the protocol-specified definitions of bleeding events in both PRASFIT studies were based on the TIMI criteria [21] and may not be directly comparable with the definitions used in more recently implemented studies, the bleeding events were also classified using the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium criteria [22]. This analysis yielded similar distributions of bleeding events to those obtained using the protocol-specified criteria [23].

Bleeding events were also examined as safety endpoints in TRITON-TIMI 38 [10]. In particular, the incidences of non-CABG-related TIMI major bleeding (2.4 vs. 1.8%; HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.03–1.68, P = 0.03), life-threatening TIMI major bleeding (1.4 vs. 0.9%; HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.08–2.13, P = 0.01), major or minor TIMI bleeding (5.0 vs. 3.8%; HR 1.31, 95% CI 1.11–1.56, P = 0.002) were greater in the prasugrel group than in the clopidogrel group.

Considering the efficacy results of both PRASFIT studies, it seems that the adjusted dosing regimen of prasugrel was at least as effective as clopidogrel in terms of reducing the risk of MACE, consistent with TRITON-TIMI 38. Notably, prasugrel did not substantially increase the risk of bleeding events compared with clopidogrel in the PRASFIT studies, unlike that observed in TRITON-TIMI 38. The most logical explanation for this finding is that the lower prasugrel dose used in both PRASFIT studies did not induce excessive platelet inhibition, reducing the risk of major bleeding events. In a post hoc analysis of PRASFIT-ACS [24], the mean PRU was significantly lower in the prasugrel group than in the clopidogrel group throughout the treatment period. However, the mean PRU for prasugrel was greater in PRASFIT-ACS than the PRU reported in a study using loading/maintenance doses of 60/10 mg [25]. These results may help explain why the adjusted prasugrel dosing regimen in PRASFIT-ACS comprising loading/maintenance doses of 20/3.75 mg showed similar efficacy to the prasugrel regimen used in TRITON-TIMI 38, without increasing the risk of bleeding.

Factors associated with major, minor, and clinically relevant bleeding in the PRASFIT studies

In PRASFIT-ACS, the incidence of the composite of major, minor, and clinically relevant bleeding was 9.6% in both the prasugrel and clopidogrel groups. Potential predictors of this composite endpoint were evaluated in post hoc analyses of PRASFIT-ACS and PRASFIT-Elective combined. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was applied to estimate HRs with corresponding 95% CIs for various bleeding events with adjustment for the following covariates: disease type (ACS vs elective), sex, body weight, age, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and complications. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2010. The results are shown in Table 2. ACS was found to be a significant predictor of this endpoint. Accordingly, in this section, we focus on the PRASFIT-ACS study and risk of major, minor, and clinically relevant bleeding in ACS patients.

Several sub-analyses of the PRASFIT studies have been conducted to elucidate the factors associated with bleeding events in these studies. The efficacy and safety results of TRITON-TIMI 38 and the PRASFIT studies should be discussed in the context of the therapeutic window of antiplatelet activity. This concept implies that the risk of thrombotic events is increased in patients with high on-treatment platelet reactivity (i.e., low platelet inhibition), and that the risk of bleeding is increased in patients with low on-treatment platelet reactivity (i.e., high platelet inhibition) [26,27,28,29].

This possibility was assessed in a subanalysis of PRASFIT-ACS, in which a composite of major, minor, and clinically relevant bleeding in the acute (up to day 3) or chronic (from day 4 to 14 days after treatment discontinuation) was plotted against P2Y12 reaction units (PRU) and the vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein-phosphorylation reactivity index (VASP-PRI) measured at 5–12 h after the LD or in steady-state conditions (week 4) [20]. The composite of bleeding occurred in 9.6% of patients in each group. As illustrated in Fig. 2, on-treatment platelet reactivity was not associated with the incidence of bleeding events. An updated consensus on the definitions of on-treatment platelet reactivity to adenosine diphosphate and the risk of ischemic events and bleeding [30] proposed cutoff values for PRU (<85) and VASP-PRI (<16) for low on-treatment platelet reactivity and recommended that PRU and VASP-PRI should be kept above these values to reduce the risk of bleeding in clinical practice. Intriguingly, when we defined on-treatment platelet reactivity using these cutoff values, we found that the risk of bleeding in these patients was similar to that obtained using the other cutoff values [20]. These results imply that the risk of bleeding is not increased in patients with low on-treatment platelet reactivity. However, the number of patients with low on-treatment platelet reactivity defined using these cutoff values was low, so further study is needed to consider the relationship between the risk of bleeding and platelet reactivity.

Reprinted from [20]

Distribution of P2Y12 reaction units (PRU) and types of bleeding events according to the PRU in PRASFIT-ACS. a PRU at 5–12 h after the loading dose and bleeding events up to 3 days after starting treatment. b PRU at 4 weeks after the loading dose and bleeding events from 4 days after starting treatment with prasugrel or clopidogrel to 14 days after treatment discontinuation. PRU P2Y12 reaction units.

Possible predictors of bleeding events were also evaluated in univariate and multivariate analyses. As shown in Table 3, sex, body weight, age, and diabetes were significantly associated with bleeding in PRASFIT-ACS, but the use of prasugrel or clopidogrel was not associated with bleeding [20].

The influence of CYP2C19 allelic variants on platelet aggregation and MACE was also assessed in post hoc analyses of PRASFIT-ACS. However, consistent with the notion that prasugrel is hardly metabolized and activated by CYP2C19, reduced/loss-of-function alleles did not appreciably affect the incidence of major, minor, and clinically relevant bleeding events (Table 4) [23].

Another potential factor that might influence bleeding events is the type of access route used. In particular, the incidence of bleeding was consistently lower in patients who underwent PCI via a radial access route than in patients who underwent PCI via a femoral access route [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. A post hoc analysis of the PRASFIT studies was, therefore, conducted to examine whether the incidence of bleeding following PCI in Japanese patients varied by access site [38]. In that analysis, the incidence of bleeding events up to 3 days after PCI was compared according to the access route used.

Consistent with prior studies, the incidence of bleeding events was lower in patients who underwent PCI via the radial access route than in patients who underwent PCI via the femoral access route in PRASFIT-ACS. Meanwhile, in PRASFIT-Elective, there were no bleeding events in this period of time in patients who underwent PCI via the radial access route (Fig. 3).

Reprinted from [38]

Incidence of major or minor bleeding at the puncture site according to access route and allocated treatment (prasugrel or clopidogrel) in a, b PRASFIT-ACS and c, d PRASFIT-Elective according to the a, c femoral or b, d radial artery access routes. The values in brackets on each bar represent the numbers of patients with an event. *Fisher’s exact test.

The predictors of bleeding were also assessed in a post hoc analysis of the TRITON-TIMI 38 study [39]. In that series of analyses, multivariable Cox regression was conducted to identify possible predictors for serious bleeding defined as TIMI major or minor bleeding. The regression models were adjusted for treatment group, as well as baseline and procedural variables. The authors found that female sex, use of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, duration of intervention, age, assignment to prasugrel, regional characteristics, admission diagnosis of ST-elevation MI, femoral access for angiography, creatinine clearance, hypercholesterolemia, and arterial hypertension were independent risk factors for serious bleeding. In PRASFIT-ACS, female sex, body weight, age, and present of diabetes were independently associated with bleeding events, defined as a composite of TIMI major bleeding, TIMI minor bleeding, and clinically relevant non-major or minor bleeding. The study treatment was included as an explanatory variable in the multivariable model, but it was not associated with the composite bleeding endpoint. This lack of association between the study drug and the composite bleeding endpoint in the multivariable model with similar incidences of individual types of bleeding events is shown in Table 1.

Other bleeding

In PRASFIT-ACS, the incidence of other bleeding was significantly greater in the prasugrel group than in the clopidogrel group. However, the incidence of spontaneous bleeding was not significantly different between the two groups. This suggests that the higher incidence of bleeding is driven by extrinsic factors, such as PCI, in the prasugrel group. In post hoc CYP2C19 analyses of PRASFIT-ACS (Table 4), the incidence of other bleeding in intermediate metabolizers (IM) and poor metabolizers (PM) of antiplatelet drugs (based on CYP2C19 phenotypes) was higher in the prasugrel group than in the clopidogrel group. However, an additional analysis, which was performed to compare the incidence of other bleeding between prasugrel-treated IM + PM patients and clopidogrel-treated extensive metabolizer (EM) patients, revealed that the incidence in prasugrel-treated IM + PM patients was similar to that in clopidogrel-treated EM patients (44.7 vs. 41.5%; HR 1.14; 95% CI 0.83–1.58). By contrast, among those treated with clopidogrel, the incidence of other bleeding in IM + PM patients was significantly lower than that in EM patients (26.2 vs. 41.5%; HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.43–0.87). The incidence of other bleeding in prasugrel-treated EM patients was similar to that in clopidogrel-treated EM patients (43.8 vs. 41.5%; HR 1.15; 95% CI 0.80–1.65). Considering these results, the incidence of other bleeding in prasugrel-treated patients, regardless of the patient’s CYP2C19 phenotype, is similar to that in clopidogrel-treated EM patients.

Bleeding as a risk factor for recurrent bleeding

Because the occurrence of a bleeding event may increase the risk of recurrent bleeding events, a further post hoc subanalysis was conducted to determine whether an initial bleeding event (classified as other) was associated with the recurrence of aggravation of subsequent bleeding events. Because of the low number of events, patients who experienced other bleeding (all bleeding other than major bleeding, minor bleeding, or clinically relevant non-major or minor bleeding events) at least once from both studies were pooled together, and the outcome was defined as a bleeding occurring ≥1 day after the initial “other” bleeding event. The incidence rates of each type of bleeding event were calculated for events that occurred between ≥1 day after the initial “other” bleeding and up to 14 days after discontinuation of the study drug. Figure 4 shows the results of this pooled analysis. Overall, about one third of patients with an initial bleeding event experienced subsequent bleeding events, but there were no differences in the types of bleeding events between patients treated with prasugrel or clopidogrel. This new analysis indicates that there was no difference between prasugrel and clopidogrel in terms of the impact of an initial bleeding event on the occurrence of recurrent bleeding events or worsening of the initial bleeding event.

Conclusions

There are several important findings raised in this review. First, the bleeding risk with prasugrel at the doses (20/3.75 mg) adjusted for Japanese patients is similar to that observed with the standard dose of clopidogrel (300/75 mg). Consistent results were obtained when bleeding events were re-classified using the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium criteria. The post hoc analyses revealed no relationship between the pharmacodynamics of prasugrel and the risk of bleeding events. The main risk factors for bleeding events were female sex, low body weight, advanced age, and presence of diabetes mellitus, which differed from those reported in the TRITON–TIMI 38 study. The risk of bleeding during PCI could be reduced using a radial puncture site rather than a femoral puncture site. The incidence of bleeding in prasugrel-treated patients, regardless of the CYP2C19 phenotype, was similar to that in clopidogrel-treated EM patients. Finally, the frequency and severity of recurrent bleeding events during continued treatment were similar between prasugrel and clopidogrel.

Overall, the results presented in this review provide important insights into the risk and types of bleeding events in prasugrel-treated patients. These findings should also help reassure clinicians that prasugrel is effective in terms of reducing the risk of MACE without increasing the risk of bleeding events after PCI in Japanese patients.

References

Hata J, Kiyohara Y. Epidemiology of stroke and coronary artery disease in Asia. Circ J. 2013;77:1923–32.

Ohira T, Iso H. Cardiovascular disease epidemiology in Asia: an overview. Circ J. 2013;77:1646–52.

Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, Adams CD, Bridges CR, Casey DE Jr, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:645–81. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.004.

Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC Jr, King SB 3rd, Anderson JL, Antman EM, et al. 2009 Focused Updates: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (updating the 2004 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI Guidelines on Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (updating the 2005 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2009;120:2271–306. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.109.192663.

Oliphant CS, Trevarrow BJ, Dobesh PP. Clopidogrel response variability: review of the literature and practical considerations. J Pharm Pract. 2015;. doi:10.1177/0897190015615900.

Farid NA, Payne CD, Small DS, Winters KJ, Ernest CS 2nd, Brandt JT, et al. Cytochrome P450 3A inhibition by ketoconazole affects prasugrel and clopidogrel pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics differently. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:735–41. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100139.

Rehmel JL, Eckstein JA, Farid NA, Heim JB, Kasper SC, Kurihara A, et al. Interactions of two major metabolites of prasugrel, a thienopyridine antiplatelet agent, with the cytochromes P450. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:600–7. doi:10.1124/dmd.105.007989.

Gurbel PA, Bergmeijer TO, Tantry US, ten Berg JM, Angiolillo DJ, James S, et al. The effect of CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prasugrel 5-mg, prasugrel 10-mg and clopidogrel 75-mg in patients with coronary artery disease. Thromb Haemost. 2014;112:589–97. doi:10.1160/th13-10-0891.

Small DS, Farid NA, Payne CD, Konkoy CS, Jakubowski JA, Winters KJ, et al. Effect of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on the clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prasugrel. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:777–98. doi:10.2165/11537820-000000000-00000.

Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001–15. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706482.

Saito S, Isshiki T, Kimura T, Ogawa H, Yokoi H, Nanto S, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjusted-dose prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in Japanese patients with acute coronary syndrome: the PRASFIT-ACS study. Circ J. 2014;78:1684–92.

Isshiki T, Kimura T, Ogawa H, Yokoi H, Nanto S, Takayama M, et al. Prasugrel, a third-generation P2Y12 receptor antagonist, in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ J. 2014;78:2926–34.

Kimura T, Isshiki T, Ogawa H, Yokoi H, Yamaguchi T, Ikeda Y. Randomized, double-blind, dose-finding, phase II study of prasugrel in Japanese patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015;22:557–69. doi:10.5551/jat.26013.

Damman P, Varenhorst C, Koul S, Eriksson P, Erlinge D, Lagerqvist B, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention treated with prasugrel or clopidogrel (from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry [SCAAR]). Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:64–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.09.019.

Brener SJ, Oldroyd KG, Maehara A, El-Omar M, Witzenbichler B, Xu K, et al. Outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction treated with clopidogrel versus prasugrel (from the INFUSE-AMI trial). Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1457–60. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.02.002.

Clemmensen P, Roe MT, Hochman JS, Cyr DD, Neely ML, McGuire DK, et al. Long-term outcomes for women versus men with unstable angina/non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction managed medically without revascularization: insights from the TaRgeted platelet Inhibition to cLarify the Optimal strateGy to medicallY manage Acute Coronary Syndromes trial. Am Heart J. 2015;170(695–705):e695. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2015.06.011.

Klingenberg R, Heg D, Raber L, Carballo D, Nanchen D, Gencer B, et al. Safety profile of prasugrel and clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes in Switzerland. Heart. 2015;101:854–63. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306925.

Roe MT, Goodman SG, Ohman EM, Stevens SR, Hochman JS, Gottlieb S, et al. Elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes managed without revascularization: insights into the safety of long-term dual antiplatelet therapy with reduced-dose prasugrel versus standard-dose clopidogrel. Circulation. 2013;128:823–33. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002303.

Wilcox R, Iqbal K, Costigan T, Lopez-Sendon J, Ramos Y, Widimsky P. An analysis of TRITON–TIMI 38, based on the 12 month recommended length of therapy in the European label for prasugrel. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:2193–205. doi:10.1185/03007995.2014.944638.

Nishikawa M, Isshiki T, Kimura T, Ogawa H, Yokoi H, Miyazaki S, et al. No association between on-treatment platelet reactivity and bleeding events following percutaneous coronary intervention and antiplatelet therapy: a post hoc analysis. Thromb Res. 2015;136:947–54. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2015.09.014.

Wiviott SD, Antman EM, Gibson CM, Montalescot G, Riesmeyer J, Weerakkody G, et al. Evaluation of prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: design and rationale for the TRial to assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by optimizing platelet InhibitioN with prasugrel Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 38 (TRITON–TIMI 38). Am Heart J. 2006;152:627–35. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2006.04.012.

Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–47. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.110.009449.

Miyazaki S, Isshiki T, Kimura T, Ogawa H, Yokoi H, Nishikawa M, et al. Re-evaluation of bleeding events in the Japanese PRASFIT-Elective and PRASFIT-ACS clinical trials using the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium criteria. Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2015;4:5. doi:10.4172/2329-6607.1000162.

Nakamura M, Isshiki T, Kimura T, Ogawa H, Yokoi H, Nanto S, et al. Optimal cutoff value of P2Y12 reaction units to prevent major adverse cardiovascular events in the acute periprocedural period: post hoc analysis of the randomized PRASFIT-ACS study. Int J Cardiol. 2015;182:541–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.01.026.

Varenhorst C, James S, Erlinge D, Braun OO, Brandt JT, Winters KJ, et al. Assessment of P2Y(12) inhibition with the point-of-care device VerifyNow P2Y12 in patients treated with prasugrel or clopidogrel coadministered with aspirin. Am Heart J. 2009;157:562.e561–9. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.021.

Blindt R, Stellbrink K, de Taeye A, Muller R, Kiefer P, Yagmur E, et al. The significance of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein for risk stratification of stent thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:1329–34.

Bonello L, Mancini J, Pansieri M, Maillard L, Rossi P, Collet F, et al. Relationship between post-treatment platelet reactivity and ischemic and bleeding events at 1-year follow-up in patients receiving prasugrel. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1999–2005. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04875.x.

Cuisset T, Frere C, Quilici J, Gaborit B, Castelli C, Poyet R, et al. Predictive values of post-treatment adenosine diphosphate-induced aggregation and vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein index for stent thrombosis after acute coronary syndrome in clopidogrel-treated patients. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1078–82. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.007.

Cuisset T, Grosdidier C, Loundou AD, Quilici J, Loosveld M, Camoin L, et al. Clinical implications of very low on-treatment platelet reactivity in patients treated with thienopyridine: the POBA study (Predictor of Bleedings with Antiplatelet drugs). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:854–63. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2013.04.009.

Tantry US, Bonello L, Aradi D, Price MJ, Jeong YH, Angiolillo DJ, et al. Consensus and update on the definition of on-treatment platelet reactivity to adenosine diphosphate associated with ischemia and bleeding. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2261–73. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.101.

Bernat I, Horak D, Stasek J, Mates M, Pesek J, Ostadal P, et al. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by radial or femoral approach in a multicenter randomized clinical trial: the STEMI-RADIAL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:964–72. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.1651.

Jolly SS, Yusuf S, Cairns J, Niemela K, Xavier D, Widimsky P, et al. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography and intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes (RIVAL): a randomised, parallel group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1409–20. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60404-2.

Lee MS, Wolfe M, Stone GW. Transradial versus transfemoral percutaneous coronary intervention in acute coronary syndromes: re-evaluation of the current body of evidence. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:1149–52. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2013.08.003.

Mamas MA, Ratib K, Routledge H, Fath-Ordoubadi F, Neyses L, Louvard Y, et al. Influence of access site selection on PCI-related adverse events in patients with STEMI: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Heart. 2012;98:303–11. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300558.

Mehta SR, Jolly SS, Cairns J, Niemela K, Rao SV, Cheema AN, et al. Effects of radial versus femoral artery access in patients with acute coronary syndromes with or without ST-segment elevation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2490–9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.050.

Romagnoli E, Biondi-Zoccai G, Sciahbasi A, Politi L, Rigattieri S, Pendenza G, et al. Radial versus femoral randomized investigation in ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: the RIFLE-STEACS (Radial Versus Femoral Randomized Investigation in ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2481–9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.017.

Sciahbasi A, Pristipino C, Ambrosio G, Sperduti I, Scabbia EV, Greco C, et al. Arterial access-site-related outcomes of patients undergoing invasive coronary procedures for acute coronary syndromes (from the ComPaRison of Early Invasive and Conservative Treatment in Patients With Non-ST-ElevatiOn Acute Coronary Syndromes [PRESTO-ACS] Vascular Substudy). Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:796–800. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.049.

Saito S, Isshiki T, Kimura T, Ogawa H, Yokoi H, Nishikawa M, et al. Impact of arterial access route on bleeding complications in Japanese patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention- insight from the PRASFIT trial. Circ J. 2015;79:1928–37. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0276.

Hochholzer W, Wiviott SD, Antman EM, Contant CF, Guo J, Giugliano RP, et al. Predictors of bleeding and time dependence of association of bleeding with mortality: insights from the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38 (TRITON–TIMI 38). Circulation. 2011;123:2681–9. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.110.002683.

Acknowledgements

The PRASFIT-Elective and PRASFIT-ACS studies were sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Co., Ltd. Medical writing services were funded by Daiichi Sankyo, Co., Ltd. The authors also thank Nicholas D. Smith, PhD, for medical writing support, which was funded by Daiichi Sankyo, Co., Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Masakatsu Nishikawa has received honoraria from Sanofi Co. and Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. and research funding from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.; Takaaki Isshiki has received honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., MSD K.K., and Sanofi K.K., and patent fees from NIPRO Corporation; Takeshi Kimura has received honoraria, clinical research funding, and other research funding from Daiichi Sankyo Co, Ltd and Sanofi K.K.; Hisao Ogawa has received honoraria from AstraZeneca K.K., Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., Boehringer Ingelheim Japan, Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD K.K., Pfizer Japan Inc., Sanofi K.K., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., clinical research funding from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., and other research funding from Astellas Pharma Inc., AstraZeneca K.K., Boehringer Ingelheim Japan, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Kowa Company, Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD K.K., Novartis Pharma K.K., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shionogi & Co., Ltd., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Hiroyoshi Yokoi has received honoraria from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., MSD K.K., and Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., and clinical research funding from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Shunichi Miyazaki has received honoraria and clinical research funding from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. and MSD K.K.; Yasuo Ikeda has received honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., and research grants from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. and Sanofi K.K.; Masato Nakamura has received honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Sanofi K.K., and AstraZeneca K.K., clinical research funding from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. and Sanofi K.K., and other research funding from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Sanofi K.K., AstraZeneca K.K. Yuko Tanaka is an employee of Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. and undertook the data processing and statistical analysis; Shigeru Saito is a medical advisor for Terumo and has received honoraria from Abbot Vascular Japan, Boston Scientific Japan, and Medtronic.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishikawa, M., Isshiki, T., Kimura, T. et al. Risk of bleeding and repeated bleeding events in prasugrel-treated patients: a review of data from the Japanese PRASFIT studies. Cardiovasc Interv and Ther 32, 93–105 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12928-016-0452-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12928-016-0452-7