Abstract

Objectives

Despite sexual minority (SM), i.e. individuals who identify as lesbian women, gay men, bisexual, or pansexual, individuals presenting worse mental health outcomes when compared to heterosexual individuals, they face more difficulties in accessing affirmative and quality health services. This study is a mixed-method non-randomized single-arm trial targeting SM individuals assessing the feasibility and exploratory findings from an affirmative mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion-based group intervention (Free2Be).

Method

Eighteen participants who self-identified as SM, with a mean age of 30.80 years old, underwent a face-to-face group intervention with 13 weekly sessions (Free2Be). Feasibility was assessed in three domains (acceptability, practicality, and preliminary effectiveness) with self-report questionnaires and hetero-report interviews, during and after the intervention, and using a mixed-methods approach. Using a pre–post and participant-by-participant design, changes were assessed in self-reported internalized stigma, psychopathology indicators, and mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion processes.

Results

The Free2Be was acceptable and feasible in all three domains. Participants who completed the intervention (≥ 80% of attendance) revealed significant or reliable decreases in stress and social anxiety symptoms, self-criticism, and fear of compassion for the self.

Conclusions

The study provides evidence of the feasibility of the intervention. This affirmative mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion-based group intervention seems to be feasible and acceptable for SM individuals. These promising findings warrant further investigation within a pilot study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Sexual minority (SM) individuals are a diverse population which includes monosexual individuals (e.g., gay men and lesbian women), bi + individuals (e.g., bisexual, pansexual, queer), and a spectrum of asexual sexual orientations (American Psychological Association, 2021). These identities experience stigmatization by heteronormative and heterosexist cultures. Heteronormativity is the assumption that heterosexuality is the standard for defining normal sexual behaviour (APA, 2023a; Warner, 1991) and heterosexism is the ideological system which denies and stigmatizes any non-heterosexual form of behaviour, identity, relationship, or community (APA, 2023b; Herek, 1990). Not surprisingly, SM individuals present poorer mental health indicators when compared to their heterosexual peers, namely mental disorders, shame, substance abuse, suicidal ideation, and self-harm behaviours (King et al., 2008; Nappa et al., 2022; Ross et al., 2018; Santos, 2021). The Minority Stress Model has been proposed to elucidate the consequences and impact of stigma on SM individuals’ mental health and conceptualizes two types of stressors: distal and proximal. Distal stressors correspond to objective events directly related to social stigma and do not depend on individual subjective perspective (e.g., macroaggressions and microaggressions). Proximal stressors are related to subjective and inner events, that is, the cognitive and emotional processing of social stigma, and include expectations of rejection, concealment of sexual orientation, and internalized stigma (Frost & Meyer, 2023; Meyer, 2003).

The mental health disparities experienced by SM individuals are exacerbated by the difficulties they face in accessing adequate and affirmative healthcare services. Due to minority stress processes and difficulties, most SM and other minority gender identities individuals that resorted to specialized services were searching for psychotherapy (69.80%), facing many difficulties when accessing the health care they need (Saleiro et al., 2022). The lack of education and information on sexuality-related themes by health professionals and their difficulty in approaching sexual identity issues mirrors the (in)visibility of non-normative sexuality in health contexts and the non-affirmative current interventions (Albuquerque et al., 2016; Lopes et al., 2016; Pieri & Brilhante, 2022). In sum, minority stressors increase the risk for psychopathology and decrease the access to and benefit from affirmative evidence-based treatments (Hambrook et al., 2022).

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based psychological approach that encompasses cognitive, emotional/affective, and behavioural techniques (Hofmann et al., 2012) and it is suitable for targeting pivotal SM-specific phenomena (cf. Carvalho et al., 2022; Pachankis, 2014). More recent CBT approaches encompassing a diverse range of client situations incorporate interventions focused on mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion (Gilbert, 2010; Hayes, 2004; Kennedy & Pearson, 2021): as example, mindfulness-based interventions (MBI; Ivtzan, 2020; Kabat-Zinn, 1994), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 1999, 2012), Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT; Gilbert, 2009, 2010; Gilbert & Simons, 2022), and Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC; Germer & Neff, 2019; Neff & Germer, 2013). Mindfulness refers to a conscious choice and intention to focus attention on what is happening here and now, with curiosity, openness, and without judgment, regardless of whether the experience is positive, negative, or neutral (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). Acceptance is also a voluntary adoption of an open, receptive, flexible, and nonjudgmental attitude toward the present moment supported by a willingness to connect with unpleasant internal experiences or situations and interactions that will likely trigger them (Hayes et al., 2012). Self-compassion is related to a sensitivity to one’s own suffering with a deep commitment to alleviate and/or prevent it (Gilbert, 2005). Additionally, the affirmative approach promotes self-determination of SM individuals and recognizes them as natural part of human diversity (American Psychological Association, 2021; Skinta, 2021). This approach also requires professionals to respect and celebrate different identities while validating the oppression felt by SM individuals, valuing each individual, and avoiding stereotypes (Mendoza et al., 2020).

The CBT processes underlying the abovementioned CBT therapies (i.e. mindfulness, acceptance, and self-compassion) have been proven to be useful and positive also for SM persons. In fact, a systematic review of mindfulness-based (MBCT and MBSR) and mindfulness-informed (ACT, DBT, MSC, and CCT) interventions highlighted the improvement of behavioural outcomes and health indicators for Sexual and Gender Minority individuals (SGM; Sun et al., 2021). Specifically, SGM young adults reported that mindfulness increased the sense of psychological safety and the development of valuable insights for emotional regulation (Iacono et al., 2022). Another systematic review of ACT with SGM individuals showed that this intervention helped to increase psychological flexibility and, consequently, to decrease negative mental health indicators (Fowler et al., 2022). Specifically, acceptance promoted a shift in the relationship with unhelpful cognitions (e.g. internalized homophobia) and empowerment in self-expression (Stitt, 2022). Also, self-compassion was found to be negatively associated with minority stressors (Helminen et al., 2022) and with negative mental health outcomes among SM individuals (e.g., depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, internalized stigma; Carvalho & Guiomar, 2022). Specifically, SGM young adults indicated self-compassion as a coping strategy against stigma, using the compassionate self in physical, psychological, interpersonal, and societal challenges (Iacono et al., 2022). Furthermore, affirmative and adapted interventions for SM persons had a better acceptability, when compared to standard interventions (Iacono et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2021).

To the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence-based psychological intervention, adapted for SM individuals, which integrates mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion in the same programme. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to describe the development and assess the feasibility of a new affirmative mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion-based group intervention for SM individuals (Free2Be), in order to explore the viability of a pilot study. Specifically, this study aimed to assess feasibility according to three domains proposed by Bowen et al. (2009), namely acceptability, practicality, and preliminary effectiveness, during and after the intervention, and using a mixed-method approach (quantitative and qualitative).

Method

Participants

Eighteen participants were recruited and distributed into three intervention groups according to the proximity of residence. There were three groups in three Portuguese cities (Coimbra, Lisbon, and Oporto). The mean age was 30.80 years old (SD = 9.70). Considering gender, 55.60% self-identified as men, 27.80% as women, and 16.70% as non-binary individuals. Considering sexual orientation, 27.80% self-identified as gay, 27.80% as pansexual, 22.20% as lesbian, 16.70% as bisexual, and 5.60% as queer individuals. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

Participants were included according to the following criteria: (1) majority (> 18 years old); (2) SM self-identified; (3) residence in Portugal; (4) perfectly understanding of Portuguese oral and written language; and (5) informed and free consent. The following exclusion criteria were used: (1) currently receiving individual or group therapy; (2) Major Depressive Disorder – severe specifier (according to the DSM-5); (3) Hypo/maniac Episode – without full remission (according to the DSM-5); (4) Psychosis Characteristics in the last 2 months (according to the DSM-5); (5) social impairment from Substance Use Disorder (according to the DSM-5); and (6) high suicide risk (according to the Suicide Risk Index). These criteria were chosen to optimize participant safety and ensure that the study results were both accurate and meaningful.

Procedure

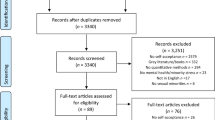

The current study is a single-armed pre-post psychological intervention study with an embedded qualitative and quantitative process of feasibility assessment. Participants who met the inclusion criteria for the study received the Free2Be intervention (experimental group). All the methodology initially projected was followed during this study. This paper is reported according to the CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials (Eldridge et al., 2016), and considering the adjustments and omissions for non-randomised feasibility studies (Lancaster & Thabane, 2019). Online Resource 1 (Supplementary Information) provides a complete checklist. Additionally, this investigation was approved by the Ethics Committee of the host institution on the 2nd of November 2019. All participants filled out an informed and free consent concerning their participation.

The recruitment happened in two phases. First, the researchers resorted to a database with potential participants that had shown a willingness to participate in a previous phase of a larger investigation (cross-sectional study on mental health in SM individuals). In a second moment recruitment was made through an online call on social media and shared in the LGBTQIA + Portuguese Services’ newsletter (these services are recognized as specialized on LGBTQIA + by the Portuguese Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality and have their own psychological services). There was no financial compensation for participation.

Regarding the eligibility interview, several structured clinical diagnostic interviews were used, namely the Clinical Interview for Bipolar Disorders (CIBD; Azevedo et. al, 2021), the Clinical Interview for Psychotic Disorders (CIPD; Martins et al., 2019), the references in the pocket guide to the DSM-5 diagnostic exam (Nussbaum, 2013), and the Suicide Risk Index (Veiga et al., 2014). These interviews assessed the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were conducted by the principal investigator (who was also a senior therapist).

The Free2Be occurred in spacious rooms with chairs arranged in a circle. The intervention setting and the coffee break space were different and clearly delimited. Two groups occurred inside LGBTQIA + services and another in the health care facility of a university. All the sessions were conducted by a main therapist and a co-therapist. Both therapist and co-therapists had a background and training in clinical CBT and had specific training in mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion techniques adapted to SM individuals.

During the intervention, participants assessed each session. At the end of the intervention, participants assessed aspects of feasibility, namely the acceptability via an online interview. Interviews were conducted by independent evaluators, had an average duration of 45 min, and were transcribed and de-identified. The interview comprised two parts: the first included quantitative data (cf. Participants-Reported Quantitative Feasibility: Acceptability) and the second included open-ended questions with qualitative data (cf. Participants-Reported Qualitative Feasibility: Acceptability).

Psychological Intervention: Free2Be

Free2Be is a manualized 13-week, face-to-face group intervention, based on mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion. It comprises one introductory session (pre-session) followed by 12 intervention sessions. This is a new and original psychological intervention developed by the authors based on different theoretical and therapeutic backgrounds considering previous research on their effectiveness. The therapeutic techniques used were derived from MBI, ACT, CFT, and MSC, and were interconnected throughout the sessions. Considering the target population, the Minority Stress Model (Frost & Meyer, 2023; Meyer, 2003) and affirmative approach are also considered, that is, depathologization of sexual orientation, normalization of some emotional difficulties as understandable responses to SM-related stress, encouragement of assertive and open self-expression to cope with SM-related consequences, validation of unique SM strengths, and the construction of an authentic relationship as an essential resource in mental health (Pachankis et al., 2022, 2023).

The pre-session lasts about 90 min, and the remaining sessions last approximately 135 min (120 min in session and a 15-min break). The pre-session includes the presentation of the main therapist, the co-therapist, and the participants, and addresses participants expectations and fears as well as safety rules. Session 1 has a different structure from the other sessions, including an overview of all contents, and setting a common language. All remaining sessions have the same structure to keep a sense of familiarity and to decrease the uncertainty and fear of the unexpected (anxiety inherent to participation in an intervention group). This general structure is as follows: (1) Welcoming; (2) Brief initial practice; (3) Discussion of the home practice; (4) Session specific content 1; (5) Poem; (6) Break; (7) Soft landing; (8) Session specific content 2; (9) Closing; and (10) Home practice. The Welcoming is an initial moment to make participants feel welcome. The Brief initial practice is a short version of a previous practice for grounding and increasing emotional willingness for the session. In the Discussion of the home practice, participants have a moment for home practices check-in, and to share their direct personal experiences in a group discussion. Session-specific contents 1 and 2 are the most extended moments in the session, including the rationale of the session’s topic(s) and related exercises or practices (also allowing some minutes for inquiry and debriefing of the practice/exercise). The Poem is related to the session’s topic and it is relevant because it highlights mindfulness, acceptance, and compassionate experiences. The Break is an important moment of relaxation and interaction between participants. The Soft landing is a brief practice to bring participants attention back to the moment and to the second part of the session, and it can also be used daily for participants’ grounding in their natural context. In Closing, a summary reminds participants of the main topics of the sessions, and in the Home practice, the therapist suggests and clarifies the therapeutic homework. Table 2 presents an overview of the Free2Be session themes, practices, and exercises (a more detailed description of each Free2Be session topic is provided in Online Resource 2).

Measures

The indicators of feasibility were assessed considering three criteria of the framework by Bowen et al. (2009) and will be presented in the following.

Participant-Reported Quantitative Feasibility: Acceptability

It was operationalized as satisfaction of each session, global satisfaction with the intervention, relevance of the sessions, perceived appropriateness of the sessions, helpfulness of the sessions, helpfulness of the participant’s manual, adequacy of the practices and exercises, and probability of recommending the Free2Be to others. Additionally, participants reported the most helpful sessions and practices. The satisfaction of each session was assessed at the end of each session with a 6-point Likert scale adapted from Campbell and Hemsley (2009; Session Rating Scale) and Quirk et al. (2013; Group Session Rating Scale) considering: respect received by the therapists in the session; respect received by group participants in the session; the approach of therapists in the session; their own involvement in the session; clarity of the session content; and the utility/helpfulness of the session. The remaining variables (e.g., global satisfaction with the intervention, helpfulness of the sessions, probability of recommending the Free2Be to others) were assessed through a post-intervention interview with an independent evaluator with a 5-point Likert scale, from nothing (1) to extremely (5).

Participant-Reported Qualitative Feasibility: Acceptability

At the end of the intervention, participants answered two questions: “What did you find positive and facilitator about this intervention?” and “What was the barriers to the embodiment of the intervention?”. Despite the questions being centred around two themes (facilitators and barriers), they were conducted in a manner that allowed participants to respond freely. Interviewers did not pose additional questions to guide the participants. Additionally, suggestions for improvement were asked.

Objective Measures of Feasibility: Practicality

It was operationalized as attendance and dropout rates (objective measures of retention).

Clinical Outcomes: Preliminary Effectiveness

Operationalized as differences in internalized stigma, psychopathology indicators, mindfulness, acceptance, and compassionate processes (fears of compassion for self, self-criticism, and psychological flexibility). Completer participants filled out self-report questionnaires pre- and post-intervention. These measures are described below.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual Identity Scale (LGBIS)

Originally from Mohr and Kendra (2011) and with a European Portuguese version from Oliveira et al., (2012), this scale has 33 items distributed in seven subscales that assess different dimensions of sexuality identity. Participants rate items on a 7-point Likert scale from totally disagree (1) to totally agree (7), with higher mean scores indicating higher levels sexuality identity dimensions. In this study, only the subscale identity dissatisfaction corresponding to internalized stigma (e.g., “I wish I were heterosexual”) was used. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.87 to 0.93 (depending on the sample) in the original version, 0.83 in the Portuguese version, and 0.91 in this study.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales – 21-Item Version (DASS-21)

Originally from Lovibond and Lovibond (1995), and with a European Portuguese version from Pais-Ribeiro et al. (2004), this scale has 21 items divided into three subscales: depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from did not apply to me at all (0) to applied to me very much or most of the time (3), with higher scores indicating greater negative affect. In this study, only stress factor was used (e.g., “I was intolerant of anything that kept me from getting on with what I was doing”). Cronbach’s alphas were 0.89 in the original version, 0.81 in the Portuguese version, and 0.89 in this study.

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS)

Originally from Mattick and Clarke (1998) and with a European Portuguese version from Pinto-Gouveia and Salvador (2001), this scale has 19 items and assesses fears of general social interaction (e.g., “I worry about expressing myself in case I appear awkward”). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all characteristic or true of me (0) to extremely characteristic or true of me (3), with higher total scores indicating higher levels of social anxiety. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.88 to 0.94 (depending on sample) in the original version, 0.90 in the Portuguese version, and 0.92 in this study.

Fears of Compassion Scale (FCS)

Originally from Gilbert et al. (2011) and with a European Portuguese version from Simões (2012), this scale assesses fears, blocks, and resistances to compassion. With three subscales, the FCS identifies barriers to giving compassion to others (10 items), to receiving compassion from others (13 items) and to giving compassion to the self (15 items). Participants rate items on a 5-point Likert scale, from don’t agree at all (0) to completely agree (4), with higher total scores indicating higher levels of fears of compassion. In this study, only fears of giving compassion to the self was used. The Cronbach’s alphas were 0.85 in the original version, 0.94 in the Portuguese version, and 0.91 in this study.

Forms of Self-criticizing/Attacking and Self-reassuring Scale (FSCRS)

Originally from Gilbert et al. (2004) and with a European Portuguese version from Castilho et al. (2015), this scale assesses how individuals typically think and react when things go wrong for them. With three subscales, the FSCRS identifies two forms of self-criticism (inadequate self and hated self) and an alternative self-to-self relationship (reassured self). Self-criticism as a composite measure that includes both the inadequate self (9 items, e.g., “There is a part of me that puts me down) and the hated self (5 items, e.g., “I have become so angry with myself that I want to hurt or injure myself”) was used. Participants rated items on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all like me (0) to extremely like me (4), with higher total scores indicating higher levels of self-criticism. The Cronbach’s alphas were 0.90 and 0.86 in the original version, ranged between 0.72 and 0.91 in the Portuguese version (depending on the sample), and 0.93 in this study.

Comprehensive Assessment of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Processes – 18 Items (CompACT-18)

Originally from Francis et al. (2016) and with a European Portuguese version from Trindade et al. (2021), this multidimensional scale assesses psychological flexibility. The CompACT-18 has three subscales: Openness to experience, with five items, e.g., “I try to stay busy to keep thoughts or feelings from coming”; Behavioural awareness, with five items, e.g., “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present”; and Valued actions, with eight items, e.g., “I make choices based on what is important to me, even if it is stressful”. Participants rate the items on a 7-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (6), with higher total scores indicating higher levels of psychological flexibility. In this study, only the total score was used. The Cronbach’s alphas were 0.84 in the original version and 0.91 in this study.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviations) were used for measures of feasibility. Due to the sample size—and in order to reduce type I error—the statistical tests used were non-parametric: Kruskal–Wallis H to explore differences between more than two groups, Z Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test as a repeated-measures analysis, and Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact to compare more categorical variables in more than two groups. These analyses were run in the SPSS v.27. The participant-by-participant design through the Reliable Change Index (RCI) for completer participants was calculated for six self-reported outcome measures corresponding to questionnaires factors and/or total. The RCI was used to calculate if there was a significant improvement, no change, or deterioration from pre- to post-intervention. \(RCI= \frac{{x}_{2}-{x}_{1}}{\sqrt{2{(SD0\sqrt{1-\alpha })}^{2}}}\), where x2 represents the result of the individual in the post-intervention, x1 represents the results of the individual in the pre-intervention, SD0 represents the standard deviation of the variable in a normative sample, and α represents the internal consistency of the scale in that same sample (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). RCI scores with a magnitude of 1.96 or greater regardless of direction (i.e. RCI ≥|1.96|) represented a reliable change (Jacobson & Truax, 1991; Zahra & Hedge, 2010) at 95%, and participants were classified as “Improved” or “Deteriorated” considering these values (Parsons et al., 2009). To compute the RCI, we searched data of the European Portuguese validations and, when existing, on Portuguese SM samples: LGBIS Identity dissatisfaction: α = 0.83, SD0gay = 1.30, SD0lesbian = 1, SD0bisexual = 1.20 (European Portuguese validation, Oliveira et al., 2012); DASS-21 Stress: α = 0.91, SD0 = 5.10 (Portuguese SM sample, Manão et al., 2024); SIAS: α = 0.94, SD0 = 1.60 (Portuguese SM sample, Santos, 2021); FCS for self: α = 0.94, SD0 = 12.40 (European Portuguese validation, Simões, 2012); FSCRS Self-criticism: α = 0.91, SD0 = 0.90; CompACT-18 Psychological flexibility: α = 0.84, SD0 = 14.10 (European Portuguese validation, Trindade et al., 2021).

For objective measures of retention, the researchers classified participants considering the number of sessions completed: completer (≥ 80% of attendance, ≥ 10 sessions) and non-completer (< 80% of attendance, < 10 sessions) (Cullen et al., 2011). Dropouts corresponded to participants that did not complete the post-intervention assessment.

For qualitative methodology, the thematic content analysis was used. Following the transcription of interviews, one researcher read and coded the content. This process followed Erlingsson and Brysiewicz's (2017) procedures, progressing from the lower level of abstraction (meaning unit as manifest content) to a higher level of abstraction (category as latent content). Specifically, the codification followed this sequence: meaning unit → condensed meaning units → code → category. Despite the questions having been open-ended, they were intentionally focused on facilitators and barriers topics. Thus, all categories belong to these themes.

Results

Participant-Reported Quantitative Feasibility: Acceptability

During the intervention, participants rated each session at the end of the sessions. Figure 1 graphically represents the scores over time of feeling respected by the therapists in session, feeling respected by group participants in the session, the appropriateness of the therapist approach in the session, their own involvement in the session, clarity of the content of the session, and the utility of the session. The general mean, considering all rates, was 4.70.

In general, almost all mean values were above 4.50, indicating very good values of acceptability. Exceptions were found only in the “involvement of participants” in the first sessions and the “approach of the therapist” in session 11. That is, the participants started the intervention with little engagement and reported gradually increasing involvement throughout the sessions. The approach of the therapists in session 11 was not well received by the participants. These aspects would be considered in the improvement of the future intervention.

After the intervention, completer participants also assessed the Free2Be. All participants expressed a very or extreme global satisfaction with the programme, and found the sessions very or extremely relevant and appropriate. The majority of participants considered the sessions (80%), and participants’ manual very or extremely helpful (90%). Seventy per cent of participants shared that the practices and exercises were very or extremely adequate. These results are detailed in Table 3.

Participants also referred that the most helpful sessions were, in descending order: session 6 (From self-criticism to self-compassion), session 11 (Driving my life), session 2 (Regulating emotions), session 3 (Where to?), session 8 (My story, my mind and me), session 9 (Who commands my ship?), and session 12 (Living fully). Considering practices, Mindfulness in daily life, Safe place, Soothing breathing rhythm, Flashcards, Soothing touch, Training acceptance, Mindful breathing, and Thanking the mind were reported as the most helpful.

Participant-Reported Qualitative Feasibility: Acceptability

With the questions made (“What did you find positive and facilitator about this intervention?” and “What was the barriers to the embodiment of the intervention?”), the researchers searched by two themes: positive and facilitative aspects of the intervention, and barriers to engaging with the intervention. Within these themes, thematic content analysis revealed several categories. For Theme 1 (facilitators), both therapist and group-related categories were identified. For Theme 2 (barriers), categories associated with group exercises, initial difficulties, and personal management were identified.

Under Theme 1 (facilitators), participants reported, specifically, the empathy, respect, proximity, and professionalism (as aspects related to therapists), and safe environment and knowledge acquired (as a group-related aspects) (codes). Some examples (meaning units) included statements such as “the therapists had good communication and respect”, and “I felt heard” (pertaining to therapists’ empathy), “no impositions” and “without ideologic discussions, respecting different points of view with acceptance” (related to therapist’ respect), “no distance between therapists and group” and “therapists showed their human side and their vulnerability” (concerning therapists’ proximity), “the group had different backgrounds, histories and ages, and the therapists have done an excellent management of this” and “professional attitude” (addressing therapists’ professionalism), “I felt comfortable with the other participants” and “good relationship with one another” (about the group’s safe environment), and “It is good to meet different people that share different stories and perspectives” and “we understood that we had to know how to listen and when to speak – it was a learning experience” (about the knowledge acquired within the group).

Into Theme 2 (barriers), participants reported, specifically, group exercises, initial difficulties, and personal management (codes). Some participants reported initial shyness and difficulty in opening up to other participants (e.g., “I felt difficulty at the beginning of the program, I was tense and felt inhibited”, “initial embarrassment”), and suggested more activities in small groups (e.g., “More exercises in small groups and not in the big group”; “More exercises in groups of two.”). Another aspect reported was related to personal management, such as “tiredness” associated with session schedules (end of the day) and “personal difficulties reconciling work and intervention schedules”). Figure 2 presents a schematic representation depicting themes, categories, and codes identified through thematic content analysis.

Finally, when asked about suggestions for improvement of Free2Be, participants referred some topics/suggestions about the recruitment and the group size. Concerning recruitment, they mentioned social networks and SM-related contexts: LGBTQIA + associations (newsletter, WhatsApp groups), LGBTQIA + services and associations, and internet pages addressed to SM individuals (e.g., online blogs and informational pages). Regarding group size, different perspectives emerged: some participants considered five to seven participants by group adequate, but other participants would prefer groups of ten participants (but no more than that), while still ensuring time/opportunity to share personal perspectives and opinions.

Objective Measures of Feasibility: Practicality

Considering the objective measure of retention, the attendance ratio was 78% (14 participants) and the dropout ratio was 22% (4 participants). Considering the participants’ attendance, ten were completer participants (71.40%) and four were non-completer participants (28.60%). Attendance ranged from 12 and 13 sessions (M = 12.50, SD = 0.50) for completers and from five and eight sessions (M = 6.30, SD = 1.50) for non-completer participants. These ratios are presented in Table 3 and the number of sessions attended by each participant is presented in Table 1.

Clinical Outcomes: Preliminary Effectiveness

The sociodemographic characteristics of all subsamples (completers, non-completers, and dropouts) can be found in Online Resource 3 (Supplementary Information). Statistic tests of comparison revealed that there were no significant differences between groups in terms of age, gender, and sexual orientation. In this sense, all three groups were considered equivalent and comparable.

All groups were compared in the pre-intervention in terms of the outcome measures: internalized stigma, stress symptoms, social anxiety, fear of compassion for self, self-criticism, and psychological flexibility. No differences were found throughout the Kruskal–Wallis H test: Hinternalized.stigma = 2.94, p = 0.23; Hstress = 2.67, p = 0.26; Hsocial.anxiety = 2.76, p = 0.25; Hfear.compassion.self = 3.94, p = 0.14; Hself.criticism = 2.04, p = 0.36; and Hflexibility = 1.14, p = 0.57.

Repeated measures of the Z Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test were performed to test differences in all variables between the pre-intervention and the post-intervention, both in completer and in non-completer participants. At post-intervention, completer participants presented a significant decrease in fear of compassion for self and in self-criticism. The remaining outcomes did not present significant differences despite the overall improvement in scores from pre- to post-intervention (all means in post-intervention were lower than in pre-intervention in negative outcomes and higher in positive outcomes). In non-completer participants, no significant differences were found in any outcome. Details are in Table 4.

Considering the reduced sample size, the analyses of participant-by-participant pre- vs post-intervention scores were performed using the Reliable Change Index (RCI) to assess the reliability of individual changes. The results are summarised in Table 5. After the intervention, 70% of completer participants reliably decreased levels of social anxiety, and 40% reliably decreased stress symptoms and their fear of compassion for self. Considering that each participant (10) was assessed in the six outcomes (60 variables), deterioration was only found in four of these variables (6.60%).

Discussion

Free2Be is the first affirmative, mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion-based group intervention for Sexual Minorities (SM) individuals. This study aimed to describe the development of the Free2Be intervention and to assess its feasibility with exploratory analyses of effectiveness, and to explore the viability to later conduct a pilot study. The framework from Bowen et al. (2009) was used for this purpose, with three indicators: acceptability, practicality, and preliminary effectiveness, during and after the intervention, and using a mixed-method approach (quantitative and qualitative). The main results highlighted good indicators of feasibility in all domains, suggesting that it may be an effective intervention for SM individuals (completer participants revealed significant or reliable decreases in stress and social anxiety symptoms, self-criticism, and fear of compassion for the self).

In general, the acceptability assessed by participants was also very good in both quantitative and qualitative results, reinforcing the pertinence and viability of a pilot study. The general mean was 4.70 (with a maximum of 5) and they considered the intervention relevant, appropriate, and helpful. In qualitative assessment by participants, some positive aspects were highlighted, namely about the utility of the intervention, therapist positive attitudes, and group environment. These results reinforcing the relevance and utility of tailored interventions for this population align with other interventions studies and recommendations (Iacono et al., 2022; Stitt, 2022; Sun et al., 2021). Pachankis et al. (2023) alert to the need of considering affirmative CBT, based on clinical practice and validated interventions, to increase awareness of the impact of minority stress on SM individuals’ mental health and in their self-perception. Additionally, the sharing of SM resilience and intersectional experiences can be a source of empowerment coping mechanism and validation of genuine relationships (Pachankis et al., 2023). The respectful, accepting, and professional posture of the therapist was also valued by the participants. In fact, it is important that therapists have an ethical and supportive relationship, and that they can help the development of strategies by the participants. Finally, the perception of the group as a safe space was referred as important. The Minority Stress Model (Frost & Meyer, 2023; Meyer, 2003) already refers the social protective factors and a safe place contributes to feelings of acceptance, connection, validation, and/or belonging through safe connections (Diamond & Alley, 2022; Gilbert, 2020; Slavich et al., 2023).

Additionally, the group intervention was revealed to be feasible considering that it was possible to retain a sufficient number of attendees. The attendance ratio was 78%, divided into 71.40% of completer participants (attended 10 or more sessions) and 28.60% non-completer participants (attended less than 10 sessions). The dropout ratio was 22% consistent with what was found in other intervention groups for SM. For example, a CBT group intervention for adult British SM with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and/or stress revealed a dropout ratio of 21.80% (Hambrook et al., 2022).

To assess the preliminary effectiveness, two types of analyses were conducted to explore the differences in clinical outcomes: mean comparisons and individual changes. Considering the means, non-completer participants did not show any significant differences in outcome measures between pre- and post-intervention. Completer participants, on the other hand, significantly decreased fears of compassion for self and self-criticism in post-intervention. That is, participants that attended more than ten sessions significantly improved their openness to empathy and action to alleviate their own suffering, and showed a significant reduction in self-critical attitudes when something fails or they fall short. These changes in psychological processes seem to show that Free2Be may be effective in improving processes associated with well-being and in the reduction of psychopathology. The remaining outcomes (internalized stigma, social anxiety symptoms, and psychological flexibility) did not present a significant difference. However, through the visual inspection of scores, there was an overall improvement, suggesting a tendency in the reduction of all outcomes.

Due to the small sample size, an RCI analysis was performed to explore the changes considering individual trajectories. Social anxiety and stress symptoms emerged as the clinical outcomes with more improvements (70 and 40% respectively), showing that the Free2Be may be effective in improving some psychopathology indicators. In general, the higher percentages in clinical outcomes represented unchanged classification, which may be interpreted as quite positive in SM individuals which have a higher degree of risk of developing those clinical symptoms. Four participants presented deterioration: participant 1 in psychological flexibility, participant 2 and 8 in social anxiety symptoms, and participant 4 in internalized stigma. In all these situations, it was possible to verify that the scores in post-intervention were still within the normative values. This fact may also be related to any life relevant life events that may cause normal fluctuations in these variables, within normative values.

In sum, positive results were found in psychological symptoms (stress and social anxiety) and compassion processes (fears of compassion for self and self-criticism), and non-significant results were found in internalized stigma and psychological flexibility. The reduction of stress symptoms is an important result considering the additional stress that SM individuals are victims due to their minority status (minority stress). Although this minority stress processes devised social stigma (Meyer, 2003), individual processes associated to the self-to-self relationship such as fears of compassion for self and self-criticism, targeted by compassion-techniques, seem to have had a positive role in reduction of stress symptoms in SM individuals. These results are in line with Iacono et al. (2022) study in which SGM young adults reported self-compassion as a coping strategy against stigma. Considering the prevalence of social anxiety disorder, heterosexual individuals presented prevalences between 2.70 and 11.50%, while nonheterosexual individual’s prevalences ranged between 6.60 and 22.30% (Mahon et al., 2021). The apparent significative and positive impact of Free2Be in social symptoms appears as clinically important, especially in this population with higher levels of social anxiety. Since social anxiety is associated with the fear of being negatively evaluated by others, we hypothesized that the Free2Be may have increased the sense of social safety. Additionally, the group modality and the sharing of personal experiences may have had an impact on the sense of common humanity and, consequently, on how one perceives the self and the others.

On the other hand, the specific proximal minority stress (internalized stigma) and psychological flexibility did not reveal a significant and/or reliable decrease, and only processes associated to self-compassion (fear of self-compassion and self-criticism) had positive results. A Compassion-Focused Therapy with other minority groups (transgender and gender non-conforming) found similar results: non-significant decrease in internalized transphobia and a significant improvement in self-compassion (Sessions et al., 2023). Despite the absence of significant changes in internalized stigma, which was an unexpected result, self-compassion interventions seem to have a positive effect on negative processes (fears of compassion and self-criticism) and stress symptoms but not on internalized stigma. A recent study of Seabra et al. (2024) that analysed the indirect effect of internalized stigma, shame, and self-criticism in the relationship between discrimination and psychological outcomes found that only shame and self-criticism revealed to be total mediators of this relationship. Despite being preliminary results, it is important to reflect about internalized stigma-focused interventions with SM individuals. Maybe the positive results in mental health indicators on SM individuals can depend, primarily, on psychological general processes such as self-compassion. In fact, self-compassion is negatively associated with minority stressors (Helminen et al., 2022) and with negative mental health outcomes among SM individuals (e.g., psychopathology and internalized stigma; Carvalho & Guiomar, 2022). More longitudinal studies are necessary to understand the processes underlying better mental health indicators. If self-compassion can function as an effective coping strategy with general stigma (Iacono et al., 2022), acceptance in psychological flexibility allows to shift the relationship with unhelpful cognitions such as internalized stigma (Stitt, 2022). Since in this study psychological flexibility did not show any significant decreases, this may account for the also not significant results in the decrease of internalized stigma. Future studies will help to better understand the relationship between these variables.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the abovementioned results and discussion, some limitations should be considered. There was no control group or random allocation in the current study, precluding the conclusion that results are exclusively due to the Free2Be. Additionally, the small sample size does not allow generalisation of these results. In this study, the size of the sample did not have enough power to explore intragroup differences (e.g., sexual orientation) or draw reliable conclusions about the programme’s efficacy.

Additionally, intersectionality was not contemplated. Previous studies reported differences, for example, in self-compassion, when analysed for more than one minority characteristic (Vigna et al., 2018, 2020). The small sample did not allow to explore the impact of other variables considering different minorized characteristics.

Considering all results and feedback, some suggestions to consider in a future pilot study emerged. To ensure a better generalisation of results, it will be relevant to have a control group, considering more sociodemographic variables, and a process of randomization when allocating participants. Furthermore, it would be important to consider other cities/residence areas to administrate the Free2Be. Additionally, the sample should be bigger to allow statistical power and more robust and reliable results. Follow-up assessments will allow further longitudinal analyses of clinical outcomes, as well as mechanisms of change.

Considering the structure and content of the psychological intervention, some changes will be considered. For example, a more explicit group dynamic for participants to get to know each other better should be included in the pre-session, which would facilitate the involvement of participants in the initial sessions. Sessions 2, 3, 8, and 10 should be reorganized, in order to be shortened. This change should keep the practices and exercises that participants highlighted. The content and topics in the session should be selected, namely in Session 10, in order to shorten the session. Sessions 2, 3, and 8 were three of the sessions reported as most helpful and the topics should be kept but simplified to shorten the session. The Passengers on the bus metaphor in session 11 should be changed from a group to an individual format to improve the involvement in the activity and the individual experience. Crosswise, all sessions should seek to integrate more moments in small groups, as suggested by participants.

In the post-intervention interview, completer participants reported some barriers to the involvement in the intervention: group exercises, initial difficulties, and personal management. To improve attendance ratios, future pilot studies should consider larger groups than this study (about 8–10 participants) that facilitate the sharing of individual experiences and perspectives, more moments in smaller groups for a decrease of the difficulty in opening up with other participants, and look into the group sessions time schedule so they do not occur at the end of the day, avoiding tiredness.

In general, all assessed domains had good values, suggesting that the Free2Be (a new, culturally tailored, mindfulness, acceptance, and compassion-based group intervention for SM in Portugal) can be effective in the intervention with SM individuals. Free2Be seems to be effective to increase positive psychological processes and to decrease psychopathology indicators. The main changes were in significant or reliable decreases in fear of compassion for self, self-criticism, social anxiety, and stress symptoms. The feasibility results were encouraging and suggest that the Free2Be is viable and would benefit from a pilot study.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

No AI services were used during the preparation of this paper.

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are not available due to the participants not having provided consent for the data to be shared.

References

Albuquerque, G. A., Garcia, C. D. L., Quirino, G. D. S., Alves, M. J. H., Belém, J. M., Figueiredo, F. W., Paiva, L. D. S., Do Nascimento, V. B., Maciel, É. D. S., Valenti, V. E., De Abreu, L. C., & Adami, F. (2016). Access to health services by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: Systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 16, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0072-9

American Psychological Association. (2021). APA Guidelines for psychological practice with sexual minority persons. www.apa.org/about/policy/psychological-practice-sexual-minority-persons.pdf

American Psychological Association. (2023a). Heteronormativity. https://dictionary.apa.org/heteronormativity

American Psychological Association. (2023b). Heterosexism. https://dictionary.apa.org/heterosexism

Azevedo, J., Martins, M. J., Castilho, P., Barreto, C., Pereira, A., & Macedo, A. (2021). Pertinence and development of CIBD - clinical interview for bipolar disorders. European Psychiatry, 64(S1), S619. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.1646

Bowen, D. J., Kreuter, M., Spring, B., Cofta-Woerpel, L., Linnan, L., Weiner, D., Bakken, S., Kaplan, C. P., Squiers, L., Fabrizio, C., & Fernandez, M. (2009). How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 452–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002

Campbell, A., & Hemsley, S. (2009). Outcome rating scale and session rating scale in psychological practice: Clinical utility of ultra-brief measures. Clinical Psychologist, 13(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284200802676391

Carvalho, S. A., & Guiomar, R. (2022). Self-compassion and mental health in sexual and gender minority people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. LGBT Health, 9(5), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2021.0434

Carvalho, S. A., Castilho, P., Seabra, D., Salvador, M. do C., Rijo, D., & Carona, C. (2022). Critical issues in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with gender and sexual minorities (GSMs). The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 15(E3). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X21000398

Castilho, P., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, J. (2015). Exploring self-criticism: Confirmatory factor analysis of the FSCRS in clinical and nonclinical samples. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 22(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1881

Ciarrochi, J., Bailey, A., & Hayes, S. C. (2008). A CBT practitioner’s guide to ACT : How to bridge the gap between cognitive behavioral therapy & acceptance & commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

Cullen, A. E., Soria, C., Clarke, A. Y., Dean, K., & Fahy, T. (2011). Factors predicting dropout from the reasoning and rehabilitation program with mentally disordered offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(3), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854810393659

Diamond, L. M., & Alley, J. (2022). Rethinking minority stress: A social safety perspective on the health effects of stigma in sexually-diverse and gender-diverse populations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 138, 104720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104720

Eldridge, S. M., Chan, C. L., Campbell, M. J., Bond, C. M., Hopewell, S., Thabane, L., Lancaster, G. A., Altman, D., Bretz, F., Campbell, M., Cobo, E., Craig, P., Davidson, P., Groves, T., Gumedze, F., Hewison, J., Hirst, A., Hoddinott, P., Lamb, S. E., … Tugwell, P. (2016). CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ, 355, i5239. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5239

Erlingsson, C., & Brysiewicz, P. (2017). A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 7(3), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001

Fowler, J. A., Viskovich, S., Buckley, L., & Dean, J. A. (2022). A call for ACTion : A systematic review of empirical evidence for the use of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy ( ACT ) with LGBTQI + individuals. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 25(July), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2022.06.007

Francis, A. W., Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2016). The development and validation of the Comprehensive assessment of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy processes (CompACT). Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 5(3), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2016.05.003

Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2023). Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Current Opinion in Psychology, 51, 101579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101579

Germer, C., & Neff, K. (2019). Teaching the mindful self-compassion program: A guide for professionals. The Guilford Press.

Gilbert, P. (Ed.). (2005). Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203003459

Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15(3), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.107.005264

Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge.

Gilbert, P. & Simons, G. (2022). Compassion focused therapy: Clinical practice and applications. Routledge.

Gilbert, P., Clarke, M., Hempel, S., Miles, J. N. V., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticizing and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466504772812959

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84(3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608310X526511

Hambrook, D. G., Aries, D., Benjamin, L., & Rimes, K. A. (2022). Group intervention for sexual minority adults with common mental health problems: Preliminary evaluation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 50(6), 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1352465822000297

Harris, R. (2019). ACT made simple (an easy-to-read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy) (2nd ed.). New Harbinger Publications.

Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 639–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80013-3

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Helminen, E. C., Ducar, D. M., Scheer, J. R., Parke, K. L., Morton, M. L., & Felver, J. C. (2022). Self-compassion, minority stress, and mental health in sexual and gender minority populations: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 30(1), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000104

Herek, G. M. (1990). The context of anti-gay violence: Notes on cultural and psychological heterosexism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 5(3), 316–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626090005003006

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1

Iacono, G., Craig, S. L., Crowder, R., Brennan, D. J., & Loveland, E. K. (2022). A qualitative study of the LGBTQ+ youth affirmative mindfulness program for sexual and gender minority youth. Mindfulness, 13(1), 222–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01787-2

Irons, C., & Beaumont, E. (2017). The compassionate mind workbook: A step-by-step guide to developing your compassionate self. Robinson.

Ivtzan, I. (2020). Handbook of mindfulness-based programmes: Mindfulness interventions from education to health and therapy. Routledge.

Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12

Jinpa, T. (2016). A fearless heart: How the courage to be compassionate can transform our lives. Hudson Strest Press.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hachette Books.

Kennedy, F., & Pearson, D. (2021). Integrating CBT and third wave therapies: Distinctive features. Routledge.

King, M., Semlyen, J., Tai, S. S., Killaspy, H., Osborn, D., Popelyuk, D., & Nazareth, I. (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-8-70

Kolts, R. L. (2016). CFT made simple: A clinician’s guide to practicing compassion-focused therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

Kolts, R. L., Bell, T., Bennett-Levy, J., & Irons, C. (2018). Experiencing compassion-focused therapy from the inside out: A self-practice/self-reflection workbook for therapists. The Guilford Press.

Lancaster, G. A., & Thabane, L. (2019). Guidelines for reporting non-randomised pilot and feasibility studies. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 5, 114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0499-1

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u

Mahon, C. P., Lombard-Vance, R., Kiernan, G., Pachankis, J. E., & Gallagher, P. (2021). Social anxiety among sexual minority individuals: A systematic review. Psychology and Sexuality, 13, 818–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.1936140

Manão, A., Seabra, D., & Salvador, M. C. (2024). Measuring shame related to sexual orientation: Validation of Sexual Minority - External and Internal Shame (SM-EISS). Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-024-00976-7

Martins, M. J., Palmeira, L., Xavier, A., Castilho, P., Macedo, A., Pereira, A. T., Pinto, A. M., Carreiras, D., & Barreiro-Carvalho, C. (2019). The Clinical Interview for Psychotic Disorders (CIPD): Preliminary results on interrater agreement, reliability and qualitative feedback. Psychiatric Research, 272, 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.176

Mattick, R. P., & Clarke, J. C. (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(4), 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10031-6

McKay, M., Greenberg, M. J., & Fanning, P. (2020). The ACT workbook for depression and shame: Overcome thoughts of defectiveness and increase well-being using acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

Mendoza, N. S., Moreno, F. A., Hishaw, A., Gaw, A. C., Fortuna, L. R., Skubel, A., Porche, M. V., Roessel, M. H., Shore, J., & Gallegos, A. (2020). Affirmative care across cultures: Broadening application. Clinical Synthesis, 18(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20190030

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Mohr, J. J., & Kendra, M. S. (2011). Revision and extension of a multidimensional measure of sexual minority identity: The lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(2), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022858

Nappa, M. R., Bartolo, M. G., Pistella, J., Petrocchi, N., Costabile, A., & Baiocco, R. (2022). “I do not like being me”: The impact of self-hate on increased risky sexual behavior in sexual minority people. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19, 737–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00590-x

Neff, K., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the Mindful Self-Compassion Program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21923

Neff, K., & Germer, C. K. (2018). The mindful self-compassion workbook: A proven way to accept yourself, build inner strength, and thrive. The Guilford Press.

Nussbaum, A. M. (2013). The pocket guide to the DSM-5™ diagnostic exam. American Psychiatric Publishing.

O’Donoghue, E. K., Morris, E. M. J., Oliver, J., Johns, L. C., & Hayes, S. C. (2013). ACT for psychosis recovery: A practical manual for group-based interventions using acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

Oliveira, J. M., Lopes, D., Costa, C. G., & Nogueira, C. (2012). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity scale (LGBIS): Construct validation, sensitivity analyses and other psychometric properties. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 334–347. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n1.37340

Pachankis, J. E. (2014). Uncovering clinical principles and techniques to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21(4), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12078

Pachankis, J. E., Harkness, A. R., Jackson, S. D., & Safren, S. A. (2022). Transdiagnostic LGBTQ-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy: Therapist guide. Oxford.

Pachankis, J. E., Soulliard, Z. A., Morris, F., & Seager van Dyk, I. (2023). A model for adapting evidence-based interventions to be LGBQ-affirmative: Putting minority stress principles and case conceptualization into clinical research and practice. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 30(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.11.005

Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., Honrado, A., & Leal, I. (2004). Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das Escalas de Ansiedade, Depressão e Stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 5(1), 229–239.

Parsons, T. D., Notebaert, A. J., Shields, E. W., & Guskiewicz, K. M. (2009). Application of reliable change indices to computerized neuropsychological measures of concussion. International Journal of Neuroscience, 119(4), 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207450802330876

Pepping, C. A., Kirby, J., & Petrocchi, N. (2017). Coming out of depression: A compassion-focused approach. Unpublished manual.

Pieri, M., & Brilhante, J. (2022). “The light at the end of the tunnel”: Experiences of LGBTQ+ adults in Portuguese healthcare. Healthcare, 10(1), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010146

Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Salvador, M. C. The social interaction anxiety scale and the social fobia scale in the Portuguese population. In Proceedings of the 31st Congress of the European Association for Behaviour and Cognitive Therapy, Istanbul, Turkey, 2 June 2001.

Quirk, K., Miller, S., Duncan, B., & Owen, J. (2013). Group Session Rating Scale: Preliminary psychometrics in substance abuse group interventions. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 13(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2012.744425

Ross, L. E., Salway, T., Tarasoff, L. A., MacKay, J. M., Hawkins, B. W., & Fehr, C. P. (2018). Prevalence of depression and anxiety among bisexual people compared to gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755

Saleiro , S. P., Menezes, N. R., & Gato, J. (2022). Estudo nacional sobre necessidades das pessoas LGBTI e sobre a discriminação em razão da orientação sexual, identidade de género e características sexuais. Comissão para a Cidadania e Igualdade.

Santos, D. L. (2021). Shame, coping with shame and psychopathology: A moderated-mediation analysis by sexual orientation. [Master’s thesis] Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of University of Coimbra. https://estudogeral.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/96518/1/Tese_Diana%20Louisa%20Santos_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 6 Jan 2023.

Seabra, D., Carvalho, S., Gato, J., Petrocchi, N., & Salvador, M. C. (2024). (Self)tainted love: Shame and self-criticism as self-discriminatory processes underlying psychological suffering in sexual minority individuals. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2024.2333777

Sessions, L., Pipkin, A., Smith, A., & Shearn, C. (2023). Compassion and gender diversity: Evaluation of an online compassion-focused therapy group in a gender service. Psychology and Sexuality, 14(3), 528–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2023.2181097

Simões, D. (2012). Medo da Compaixão: estudo das propriedades psicométricas da Fears of Compassion Scales (FCS) e estudo da sua relação com medidas de Vergonha, Compaixão e Psicopatologia. [Master’s thesis] Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of University of Coimbra. http://hdl.handle.net/10316/23280

Simón, V., & Germer, C. K. (2011). Aprender a Practicar Mindfulness. Sello Editorial.

Sinclair, M., & Beadman, M. (2016). The little ACT workbook: An introduction to acceptance and commitment therapy. Crimson.

Skinta, M. D. (2021). Contextual behavior therapy for sexual and gender minority clients: A practical guide to treatment. Routledge.

Skinta, M. D., & Curtin, A. (2016). Mindfulness and acceptance for gender and sexual minorities: A clinician’s guide to fostering compassion, connection, and equality using contextual strategies. New Harbinger Publications.

Slavich, G. M., Roos, L. G., Mengelkoch, S., Webb, C. A., Shattuck, E. C., Moriarity, D. P., & Alley, J. C. (2023). Social safety theory: Conceptual foundation, underlying mechanisms, and future directions. Health Psychology Review, 17(1), 5–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2023.2171900

Stitt, A. L. (2020). Act for gender identity: The comprehensive guide. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Stitt, A. L. (2022). Of parades and protestors: LGBTQ + affirmative acceptance and commitment therapy. Journal of LGBTQ Issues in Counseling, 16(4), 422–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/26924951.2022.2092931

Sun, S., Nardi, W., Loucks, E. B., & Operario, D. (2021). Mindfulness-based interventions for sexual and gender minorities: A systematic review and evidence evaluation. Mindfulness, 12(10), 2439–2459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01710-9

Trindade, I. A., Ferreira, N. B., Mendes, A. L., Ferreira, C., Dawson, D., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2021). Comprehensive assessment of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy processes (CompACT): Measure refinement and study of measurement invariance across Portuguese and UK samples. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 21, 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.05.002

Turrell, S. L., & Bell, M. (2016). ACT for adolescents: Treating teens and adolescents in individual and group therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

Veiga, F. A. da, Andrade, J., Garrido, P., Neves, S., Madeira, N., Craveiro, A., Santos, J. C., & Saraiva, C. B. (2014). IRIS: A new tool for suicide risk assessment. Psiquiatria Clínica, 35(2), 65–72. http://rihuc.huc.min-saude.pt/handle/10400.4/1861

Vigna, A. J., Poehlmann-Tynan, J., & Koenig, B. W. (2018). Does self-compassion covary with minority stress? Examining group differences at the intersection of marginalized identities. Self and Identity, 17(6), 687–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2018.1457566

Vigna, A. J., Poehlmann-Tynan, J., & Koenig, B. W. (2020). Is self-compassion protective among sexual- and gender-minority adolescents across racial groups? Mindfulness, 11(3), 800–815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01294-5

Walser, R. D., Sears, K., Chartier, M., & Karlin, B. E. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy for depression in veterans: Therapist manual. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. https://www.treatmentworksforvets.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ACT-D-Therapist-Manual.pdf

Warner, M. (1991). Introduction: Fear of a queer planet. Social Text, 29, 3–17.

Williams, M., Teasdale, J., Segal, Z., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (2007). The mindful way through depression - Freeing yourself from chronic unhappiness. The Guilford Press.

Zahra, D., & Hedge, C. (2010). The reliable change index: Why isn’t it more popular in academic psychology. Psychology Postgraduate Affairs Group Quarterly, 76, 14–19.

Acknowledgements

We are genuinely grateful to participants who voluntary accepted to participate in Free2Be and provide many valuable insights. The Associação Plano I, Serviços da Ação Social da Universidade de Coimbra, and ILGA Portugal were tireless providing space and logistics. Thank you for that, namely to Paula Allen, Carla Novais, António Queirós, Maria João Martins, Sara Malcato, and Gonçalo Aguiar. Additionally, thanks to my professional colleagues: eight experts who assessed Free2Be (Ana Galhardo, Catarina Rego Moreira, Julieta Azevedo, Marcela Matos, Maria João Martins, Mariana Vaz Marques, Paula Castilho, and Sérgio A. Carvalho) and four psychologists responsible for post-treatment interviews (Cláudia Pires, Diogo Carreiras, Julieta Azevedo, and Raquel Guiomar). To Andreia Manão, Tiago Castro, and Luís Pinheiro, we are grateful for your collaboration as co-therapists.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). This work was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Foundation for Science and Technology, FCT, Portugal) under Grant number SFRH/BD/143437/2019 (“Mental Health and Well-Being in Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual (LGB) People: Conceptual Model and Compassion-Based Intervention”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Daniel Seabra: conceptualization, development of the intervention, resources and material, coordination of the intervention, conducting the intervention, methodology, interpretation of results, writing an original draft of the manuscript. Jorge Gato: review and editing of the final manuscript. Nicola Petrocchi: development of the intervention, resources and materials, review and editing of the final manuscript. Maria do Céu Salvador: conceptualization, development of the intervention, resources and materials, coordination of the intervention, supervisor of the intervention, interpretation of results, review and editing of the final manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics and Deontology Commission of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

All participants gave their informed written consent before participating in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seabra, D., Gato, J., Petrocchi, N. et al. Affirmative Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Compassion-Based Group Intervention for Sexual Minorities (Free2Be): A Non-Randomized Mixed-Method Study for Feasibility with Exploratory Analysis of Effectiveness. Mindfulness (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02403-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02403-9