Abstract

Objectives

this scoping review aimed to explore the diversity of existing nature-based mindfulness (NBM) interventions. The specific objectives of this review were to (1) describe the practices and methods that are used in NBM interventions, and to (2) determine the environmental conditions that are typically associated with NBM interventions.

Method

Thirty peer-reviewed scientific studies were identified via a systematic PRISMA search protocol and then thematically analysed and categorically organised.

Results

In relation to the first research objective, a typological scheme for classifying NBM interventions was proposed in which four main categorizations of NBM interventions were identified, including (1) conventional practices combined with nature, (2) activity-based practices using nature, (3) NBM therapy practices, and (4) emerging practices. These themes demonstrate the diversity of existing NBM interventions and provide a more integrated understanding of the applicability of these interventions across different clinical and non-clinical contexts. In relation to the second research objective, existing NBM interventions were found to be conducted in (1) naturally occurring, (2) curated natural, and (3) simulated natural environments. Within these categories, a diverse range of restorative environments were identified as suitable contexts for NBM interventions, with forest-based interventions being the most commonly used environment.

Conclusions

Overall, this study contributes to a more integrated understanding of the practices, methods, and environmental conditions typical of existing NBM interventions, proposes a classification scheme for NBM interventions, and identifies a number of new developments within the field as well as promising avenues for future research and practice.

Preregistration

This study has not been preregistered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mindfulness, historically rooted in Eastern spiritual practices, has evolved significantly within secular Western contexts since the 1970s, largely due to the efforts of Jon Kabat-Zinn (Noonan, 2014; Raj & Kumar, 2019). Initially embracing a spiritual and theoretical approach, mindfulness has shifted towards a more pragmatic application in contemporary settings (Lee et al., 2021). Although today’s Western conceptualization of mindfulness incorporates central Buddhist principles and preserves foundational tenets such as wakefulness of mind and the development of insight (Nnanavamsa & Kirshnasamy, 2014; Rhys Davids & Stede, 1959), it is also recognized as a distinct, emerging cultural phenomenon (Schmidt, 2011). Thus, this modern adaptation draws from Eastern philosophy but diverges in certain respects from traditional Buddhist practices (Lee et al., 2021; Schmidt, 2011). Today, mindfulness is well-defined as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat-Zinn, 2003, p. 145).

Since its introduction into Western secular settings, several mindfulness-based practices (MBPs) have been developed, which typically cultivate mindfulness through a variety of methods that facilitate self-awareness, emotional regulation, self-compassion, and the capacity for positive change (Davis & Hayes, 2011; Janssen et al., 2018). This is achieved in most cases by applying the so-called "three pillars of mindfulness”, namely intention, attitude, and attention, which emphasize maintaining intentional focus in the here-and-now, with a non-judgmental attitude, whilst paying attention to all sensory experiences (Rush & Sharma, 2017).

As one of the first Western MBPs, Kabat-Zinn and colleagues developed Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and intended to bring the practice of mindfulness into mainstream secular settings (non-religious) to relieve debilitating anxiety and chronic pain (Marchand, 2012; Wielgosz et al., 2019). Another widely supported standardized MBP within Western contexts used to improve psychological wellbeing is Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Gotink et al., 2016; Hofmann & Gómez, 2017). Following decades of practice and research, both MBSR and MBCT are widely accepted as effective MBPs for the treatment of anxiety and depression, as well as general stress management (Gotink et al., 2016; Hofmann & Gómez, 2017; Marchand, 2012).

Another MBP that has been growing in popularity is nature-based mindfulness (NBM) (Djernis et al., 2019). NBM is a nature-incorporating mindfulness practice where nature itself, along with the relationship formed between the individual and nature, is regarded as an essential therapeutic component that is linked to improved mental health and psychological restoration (Bragg & Atkins, 2016; Choe et al., 2020a; Huynh & Torquati, 2019; Naor & Mayseless, 2021; Scopelliti et al., 2019).

Nisbet et al. (2009) viewed this person–nature relationship as an experience of connectedness to nature (CN), which can be described as “the affective, cognitive, and experiential relationship individuals have with the natural world or a subjective sense of connectedness with nature” (p. 719). This connection to nature has been associated with the capacity to develop a deepened sense of wellbeing (Howell & Passmore, 2013; Lumber et al., 2017), and is considered to be psychologically restorative (Bragg & Atkins, 2016; Scopelliti et al., 2019). Two theories that address the psychologically restorative properties of nature include attention restoration theory (ART; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989) and stress reduction theory (SRT; Ulrich, 1983), which are both rooted in the biophilia hypothesis. The term biophilia was first used by Fromm (1992) to describe “the passionate love of life and of all that is alive.” (p. 406). This was further developed by Wilson (1984) to include having an inherent affiliation for natural forms of life. Since then, it has been conceptualized as an innate tendency to positively respond to nature, which stems from the need to adapt to an evolving environment (Scopelliti et al., 2019).

SRT holds that nature-based settings have the capacity to evoke positive emotions and enhance recovery in a broad spectrum of psychological domains (Choe et al., 2020a; Herzog & Strevey, 2008). Overall, SRT is predicated on the assumption that nature plays a key role in facilitating stress recovery (Herzog & Strevey, 2008). ART, on the other hand, focuses on the restoration of functional cognitive capability, and is based on the view that nature-based settings restore limited and depleted cognitive resources, and importantly, the ability to pay attention (Choe et al., 2020a). Overall, ART posits that involuntary attention (also referred to as maintaining a soft fascination; Kaplan, 1995) to nature enhances the capacity for psychological restoration (Huynh & Torquati, 2019; Naor & Mayseless, 2021; Pearson & Craig, 2014; Scopelliti et al., 2019).

From these two theories, it is clear that intentional engagement with nature is generally supported as being psychologically restorative and conducive to higher levels of psychological wellbeing (Bragg & Atkins, 2016). Engagement with nature has been linked to a number of restorative psychological benefits. These benefits include increased positive affect and mood (Capaldi et al., 2015; Djernis et al., 2019; Hewitt et al., 2013), buffering against poor mental health or the negative health impact of stressful life events (Van den Berg & Custers, 2011), improved psychiatric symptom load such as anxiety (Sahlin et al., 2015), and enhanced overall wellbeing (McMahan & Estes, 2015).

As such, NBM is regarded as a potentially valuable mindfulness intervention for the enhancement of mental health and a variety of therapeutic outcomes (Lücke et al., 2019; Naor & Mayseless, 2021; Sahlin et al., 2015). Despite its widespread application and a significant number of research studies supporting the psychological benefits of NBM, there is little integrated knowledge concerning the practices and methods used as part of NBM interventions (Djernis et al., 2019). Similarly, while nature is widely regarded as an important restorative element that enhances therapeutic outcomes, there is no comprehensive overview of the environmental conditions that are typically used in NBM interventions (Djernis et al., 2019; Lymeus et al., 2019). These gaps likely hamper efforts at establishing a focused research agenda and effectively building on existing research. As such, a need exists to obtain a consolidated picture of scholarly work on the topic (Djernis et al., 2019); to identify any gaps in existing research; and to identify common themes that cross-cut various studies. These outcomes could provide this field with a more coherent foundation, supported by literature, which could guide and facilitate future research efforts as well as practical developments and improvement within NBM interventions.

To address the lack of integrative knowledge, the overarching aim of the scoping review study was to develop a better understanding of the diversity of contemporary NBM interventions. In order to achieve this overarching aim, the following research questions were formulated to guide the study: (1) What practices and methods are used in NBM interventions, and (2) environmental conditions are typically associated with NBM interventions?

Method

Given that the overarching aim of the study was to describe and better understand the diversity of existing NBM interventions, a scoping review was considered an ideal approach. This specific type of review is a form of knowledge synthesis that provides a comprehensive summary overview of a given topic, without necessarily developing a hypothesis, theory, or framework (Sucharew & Macaluso, 2019).

Approach and Design

The framework for scoping reviews, proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), was used for this review study. The framework consists of five stages, including: Stage 1—identifying the research question; Stage 2—identifying relevant studies; Stage 3—study selection; Stage 4—charting the data, and Stage 5—collating, summarizing, and reporting the results, as discussed next.

Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

During Stage 1, the research questions were developed to address the study's overall aim, which was to achieve an integrative understanding of NBM interventions, specifically in relation to NBM intervention-related methods, practices, and environmental conditions used in NBM interventions. To adequately address this aim, two research questions were formulated: (1) what practices and methods are used in NBM interventions, and (2) environmental conditions are typically associated with NBM interventions?

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

During Stage 2 of the review process, the following keywords were used to guide the search strategy: nature-based OR natur* OR green* OR wilderness OR outdoor* OR ecotherapy OR eco therapy OR eco-therapy OR nature-based therapy OR wilderness therapy OR horticultural therapy OR nature therapy OR nature-based intervention OR nature-assisted therapy OR restorative nature OR nature exposure OR restorative garden OR therapeutic garden OR woods OR green space AND mindfulness OR meditati* OR therapy AND methods OR interventions OR program*. Thereafter, additional keywords were identified, from the yielded results, and used to expand and enhance the search.

Stage 3: Study Selection

Stage 3 (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) involved selecting relevant studies, which included screening processes and quality appraisals of the articles identified. As per the recommendations of Arksey and O’Malley (2005), this scoping review aimed to be as comprehensive as possible when identifying potentially relevant studies. This scoping review therefore maintained a broad scope of inquiry (Brien et al., 2010) and did not have specific inclusion or exclusion criteria concerning participant demographics.

The inclusion criteria that guided the process of identifying relevant studies (Stage 3; Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) were as follows: scientific literature published over the past 12 years, peer reviewed studies that are in the English language, and only studies explicitly addressed nature and mindfulness.

The decision to use a 12-year timeframe for including studies is based on the emergence of significant literature in the field, as identified by Djernis et al. (2019). This benchmark study did not include any publications prior to 2009, as the authors noted that the field of NBM practice, despite growing in popularity in recent years, is still in its infancy (Djernis et al., 2019). Furthermore, although environmental psychology has long examined the relationship between mindfulness and restorative environments (nature), researchers have neglected, until recently, research on practice-based applications like NBM interventions and the setting in which these occur (Lymeus et al., 2019; Owens & Bunce, 2022). This gap further underscores the importance of focusing on recent studies in our current research.

The initial phase of Stage 3 involved screening the title and abstract of each article (n = 2071) as a method of determining relevance. Based on this initial process, the researcher could gauge whether the article under scrutiny addressed the research aim and objectives and whether it focused on nature-based mindfulness. This was an iterative process that required the researcher to implement and refine the search strategy, include additional articles identified through other sources, and review each article against the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria (Levac et al., 2010).

Thereafter, the remaining articles were individually assessed by reading the full article multiple times to determine eligibility (n = 203). This process was guided by the following questions: (1) Does it meet the inclusion criteria?; (2) does it meet the quality appraisal criteria set out by Dixon-Woods et al. (2006), including criteria for scientific rigour? As recommended by Levac et al. (2010), the articles were independently reviewed by two of the authors. After this, any discrepant views related to specific articles were collaboratively discussed with the aim of achieving consensus.

The appraisal process was guided by the prompts set out by Dixon-Woods et al. (2006) which were used as evaluative guidelines in determining the quality of the research articles under scrutiny. The appraisal prompts by Dixon-Woods et al. (2006) are: (1) Are the aims and objectives of the research clearly stated?; (2) is the research design clearly specified and appropriate for the aims and objectives of the research?; (3) do the researchers provide a clear account of the process by which their findings we reproduced?; (4) do the researchers display enough data to support their interpretations and conclusions?; and (5) is the method of analysis appropriate and adequately explicated?

Stage 4: Charting Data

As recommended by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), in Stage 4, data should be charted according to a specified set of categories, which, in the present study, included: author(s), year of publication, intervention type, aims of the study, methodology, and any important results. In accordance with this, the primary researcher extracted relevant data from the selected sources and tabulated these findings into a summarized format. This was also done to avoid omitting findings valuable to the synthesis (Levac et al., 2010; Noyes & Lewin, 2010). Refer to the supplementary data for summary of extracted data (Table S1).

Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Stage 5 (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) includes the analysis and reporting of the findings. Given that a scoping review is designed “to map a wide range of literature, and to envisage where gaps and innovative approaches may lie” (Ehrich et al., 2002, p. 28), the analysis aimed to address these aspects. For the analysis, Thomas and Harden’s (2008) process was followed, which included (1) coding article texts line-by-line, (2) developing descriptive themes, and (3) generating analytical themes. To enhance the accuracy and trustworthiness of the themes, and thus the scientific rigour of the study, ATLAS.ti was used to facilitate the thematic synthesis (Rambaree, 2014). The primary, secondary, and tertiary reviewers ensured that the themes identified from the analysis were reported in a methodical and descriptive manner that accurately reflected the findings.

Results

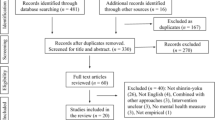

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 2,145 publications were identified from database searches (2,105) and from other sources (40). In total, 2,071 publications were screened after duplicates (128) had been removed. After screening titles and abstracts, 1,922 records were excluded based on those studies’ foci falling outside of the current research objectives. After these exclusions, 203 full-text articles emerged that were eligible for further assessment. These were assessed in accordance with the Dixon-Woods et al. (2006) protocols for quality appraisal, and the inclusion/exclusion criteria of this study. This resulted in the exclusion of a further 173 articles, leaving a total of 30 articles that were included in this review.

Figure 1 depicts the process of identifying and selecting articles in accordance with PRISMA reporting guidelines (Moher et al., 2009).

Research Objective 1: Practices and Methods Used in NBM Interventions

The first research objective focused on identifying the different methods and practices used in existing NBM interventions. From the analysis, it was apparent that NBM interventions are quite diverse, and as a result lend themselves to applications in diverse settings, ranging from clinical (e.g., focused on stress-related disorders and depression) to non-clinical (e.g., relaxation and general stress reduction) contexts. Four main themes emerged from the analysis, which, along with their corresponding sub-themes, provide a useful scheme for classifying and organising NBM interventions in accordance with the practices and methods used. These include: (1) conventional mindfulness practices combined with nature, (2) activity-based practices using nature, (3) NBM therapy practices, and (4) emerging practices.

Within each of these broad, overarching themes, several specific subthemes were identified based on the different methods of facilitating mindfulness (which refers to the mindfulness techniques used), as well as the methods of nature incorporation (which refers to the manner in which, and to what extent nature is used) that were employed. Figure 2 provides a summative graphic illustration of the emergent themes and subthemes associated with research question one, which could also serve as a scheme for classifying NBM interventions.

Theme 1: Conventional Mindfulness Practice Combined with Nature

The first theme, conventional mindfulness practices combined with nature, represents a grouping of NBM interventions that stem from pre-existing, conventional MBPs. As NBM interventions, these MBPs use conventional practices and methods, and apply these in a nature-based context. Two primary practices emerged as subthemes from the articles included in this review: (1) adapted mindfulness interventions and (2) stand-alone NBM interventions.

Adapted mindfulness interventions describe a grouping of pre-existing standardized mindfulness interventions adapted and integrated into a nature-based setting. Therefore, NBM interventions under this category comprise pre-existing MBPs conducted within a nature-based context. Examples include using mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) (Choe et al., 2020a; Djernis et al., 2019) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (Djernis et al., 2019) in a nature-based context.

MBSR and MBCT-based NBM practices comprise complete mindfulness training protocols that use a variety of attention training techniques to facilitate mindfulness (Djernis et al., 2019). The techniques include concentration meditation (i.e., object awareness), open-awareness meditation (i.e., sensory awareness), and an awareness of the present moment itself (Djernis et al., 2019). In addition to attention training, these adapted mindfulness interventions use mindful movement and body scanning to facilitate mindfulness (Choe et al., 2020a, 2020b), all within the context of a natural environment.

Overall, adapted mindfulness interventions adhere to the original MBPs’ mindfulness training protocol and, therefore, do not change the methods used to achieve a state of mindfulness. The only notable change identified in these adapted mindfulness interventions is using a nature-based context instead of a non-natural context (Choe et al., 2020a; Djernis et al., 2019). The reasoning behind this contextual change derives from the notion that nature enhances restorative processes and reflective attitudes, which facilitate the capacity to achieve a state of mindfulness (Choe et al., 2020a).

Stand-alone interventions constitute a grouping of NBM interventions designed or intended to stand as a complete intervention. Given that it is a complete NBM intervention, these MBPs cannot be implemented outside of nature-based contexts, as nature forms an integral part of the design. Therefore, the design of stand-alone interventions carefully considers both the implementation of conventional MBPs and the purposeful use of nature. This consistent emphasis on nature differs from adapted mindfulness interventions where nature can form part of, or be removed from the mindfulness intervention, since it merely serves as a setting to facilitate the development of mindfulness.

A prominent example of such a stand-alone MBP identified in the review is restoration skills training (ReST), which is an adapted version of MBSR (Djernis et al., 2019; Lymeus et al., 2020). ReST, while based on the MBSR mindfulness training protocol, is designed to capitalize on the restorative effects of nature by intentionally focusing on, or engaging with, the nature-based context (Lymeus et al., 2019, 2020). The facilitation of mindfulness in ReST, therefore, incorporates nature into different mindfulness techniques from the MBSR mindfulness training protocol (i.e., open monitoring, a Zen mindfulness method, or mindful movement; Lymeus et al., 2018, 2019) by "drawing attention to present experiences in the environment, stimulating curiosity, facilitating decentring, and restoring attention regulation capabilities” (Lymeus et al., 2020, p. 5).

In summary, conventional mindfulness practices combined with nature describe a grouping of NBM interventions that use pre-existing, conventional MBPs within a nature-based context. Within this theme, adapted mindfulness interventions and stand-alone NBM interventions emerged from the review. The central mechanism that facilitates mindfulness in these interventions is the pre-defined mindfulness training protocol that is applied in a natural setting (Choe et al., 2020a; Djernis et al., 2019). By contrast, stand-alone NBM interventions use adapted versions of conventional MBPs, such as MBSR, and nature plays a central role throughout the intervention (Lymeus et al., 2020). Thus, the mindfulness training protocol is adapted in such a manner that the method of nature incorporation cannot be removed from the intervention, which distinguishes it from adapted mindfulness interventions (Djernis et al., 2019; Lymeus et al., 2019).

Theme 2: Activity-based Practice

A second theme that was identified, activity-based practices, represent a grouping of NBM interventions that focus on various ways of being active in and engaging with nature, with the aim of facilitating a state of mindfulness. In contrast to the conventional mindfulness-based practices described above, the activity-based component of these interventions play a central role in achieving a state of mindfulness, rather than using a predefined conventional mindfulness training protocol carried out in a nature-based context. The four predominant types of practices that fall under this specific theme are (1) immersive practices, (2) adventure-based practices, (3) horticultural practices, and (4) animal-assisted practices.

Immersive practices describe a grouping of NBM interventions that are typically more passive practices and primarily focus on mindfully engaging with, or immersing oneself in, nature. This focus aims to shift attention to nature and guides the individuals to attend to the present sensory experiences in the environment (Clarke et al., 2021).

Examples of immersive practices identified in the review include different types of forest therapy interventions, also known as forest bathing (Clarke et al., 2021) or Shinrin-Yoku (Ambrose-Oji, 2013). These are considered immersive practices since forest therapies facilitate mindfulness by immersing (i.e., ‘bathing’) oneself in nature and consciously being aware of the experience in nature (Clarke et al., 2021).

One of the most common methods used to facilitate mindfulness is forest walking. This involves mindful and slowly walking in a forest while mindfully attending to one’s sensory experiences (Ambrose-Oji, 2013; Clarke et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2017; Yeon et al., 2021). Other methods that facilitate mindfulness identified in this review are forest viewing (mindfully observing and taking in the forest environment) and Qi-Qong, which is a traditional Chinese mind–body-spirit meditative practice using gentle movement or poses that are commonly performed in a natural setting (Lee et al., 2017).

Adventure-based practices describe a grouping of NBM interventions that typically incorporate adventure-based activities as the predominant method of facilitating mindfulness. These adventure-seeking activities, also referred to as nature-based activities (NBAs; Høegmark et al., 2021) or mindfulness-based experiences (MBEs; Russell et al., 2016), use adventure as the core method that aims to facilitate mindfulness.

The current review identified numerous programmes that facilitate mindfulness using adventure, such as Shunda Residential (Russell et al., 2016), the Wildman Programme (Høegmark et al., 2021), trauma-informed wilderness therapy (TWIT) (Johnson et al., 2020), and Wetland nature-based health interventions (Maund et al., 2019). These programmes typically use different types of NBAs/MBEs, including rock climbing (Russell et al., 2016), fishing (Høegmark et al., 2021; Maund et al., 2019), and trekking (Johnson et al., 2020).

Whereas immersive practices use nature in more passive ways to facilitate mindfulness, these adventure-based practice activities employ a more active approach, incorporating activities that can range from being minimally active (i.e., fishing or birdwatching; Høegmark et al., 2021; Maund et al., 2019) to substantively more active or demanding (i.e., canoeing and hiking; Russell et al., 2016). Notwithstanding the level of activity, NBAs/MBEs are used to encourage individuals to practice and develop mindfulness skills and a reflective attitude during the activity (Russell et al., 2016). Instructors/guides therefore tend to encourage continuous self-reflection and being mindful throughout the different activities. For example, encouraging the use of mindfulness-based skills during “a rock climbing experience may involve a client directly confronting his physical abilities and fear of heights, which may be related to fears that the client might have confronting stressors and post-treatment social situations that may lead to relapse and misuse” (Russell et al., 2016, p. 322). In addition to self-reflection, some adventure-based practices incorporate specific techniques or therapeutic approaches to enhance the facilitation of mindfulness in these programmes. TWIT, for example, includes techniques and approaches such as trauma-sensitive yoga, a mindfulness-based complimentary approach focusing on “a combination of breathing exercises, physical movement, and intentional relaxation” (Johnson et al., 2020, p. 880).

Horticultural-based practices describe a grouping of NBM interventions that use gardening or nature-based work to facilitate mindfulness. This review identified only one such horticultural-based practice with a direct link to the facilitation of mindfulness. While there are numerous examples of such interventions, most only contain a limited, tenuous, or implied link to mindfulness. A horticultural-based practice involves engaging with nature productively and mindfully through gardening activities such as fruit potting (Vujcic et al., 2017). In addition to the horticultural activities, dedicated rest periods in nature and meditation in nature-based contexts are added to aid the NBM intervention (Vujcic et al., 2017). The central mechanism of change therefore appears to be productive garden/nature-based work that involves contact with a restorative environment (Vujcic et al., 2017).

Animal-assisted practices describe a grouping of NBM interventions that focus on methods that aim to develop a mindful person-animal relationship. As with horticultural-based practices, findings related to animal-assisted practices are limited. Of the 203 full-text articles assessed for eligibility (Fig. 1), only one article featured an NBM intervention associated with animal-assisted practices. For this reason, the results also reflect only one source and lack confirmability.

From the identified article, the core method of facilitating mindfulness entails the development of a mindful relationship between the animal and the individual (Burgon, 2013). In this context, mindfulness skills such as body scanning (aimed to increase awareness of sensory experiences of different body parts), are conducted on/near the animal to allow the individual to stay in the present moment, increase self-awareness, and accept the here-and-now experience (Burgon, 2013). These skills increase an awareness of one’s behaviours and reactions and affect relationship formation (Burgon, 2013).

In summary, activity-based practices represent a large grouping of NBM interventions that focus on direct engagement with nature through various activities. Immersive, adventure-based, horticultural, and animal-assisted practices are distinguished from one another, but all involve different forms of active engagement with nature, or some form of physical activity in nature-based contexts as the main method used to facilitate mindfulness.

Theme 3: NBM Therapy Practice

This theme is used to describe a grouping of NBM interventions that use experiences and activities in a nature-based context that extend beyond the purpose of being a mindfulness intervention. In other words, these NBM interventions include different methods of facilitating mindfulness, but these form part of a greater therapeutic process. These NBM interventions therefore represent a combination of practices and methods from the previously discussed themes along with other therapeutic processes to achieve predefined therapeutic goals that both incorporate and extend beyond a focus on mindfulness.

The main NBM therapy practice identified in this review is nature-based therapy (NBT) (Corazon et al., 2010, 2018a, 2018b; Poulsen et al., 2016, 2018; Sidenius et al., 2017a, 2017b), also termed Nacadia NBT (NNBT) (Stigsdotter et al., 2018) and NBT in Nacadia (NBTN) (Corazon et al., 2018b). Nacadia is an evidence-based healing forest garden design located in the North American and North European parts of the arboretum (Corazon et al., 2010; Sidenius et al., 2017b; Stigsdotter et al., 2018). The design of the garden supports the NBT programme in that it offers a diverse range of meaningful therapeutic spaces that match and support the individual’s treatment process and the desired objectives of the programme itself (Sidenius et al., 2017b).

NBT is a 10-week treatment programme, with well-defined operational goals (Corazon et al., 2010). These goals are “based on the therapeutic use of sensory experiences, horticultural activities, nature-related stories, and symbols” (Corazon et al., 2010, p. 35), and are achieved by means of the four central components of NBT interventions, which are (1) individual therapeutic conversations, (2) mindfulness techniques conducted in group and individual settings, (3) nature-based activities, and (4) simply being/relaxing in nature (Corazon et al., 2018b; Sidenius et al., 2017a; Stigsdotter et al., 2018). In addition to this, these interventions typically include homework to practice the techniques that had been learnt (i.e., mindful meditation techniques) to further support the development of a mindful state and the therapeutic goals (Stigsdotter et al., 2018).

Several methods to facilitate mindfulness are employed within NBT, which includes sensory awareness exercises (i.e., body scanning techniques to enhance awareness in the present moment), mindful movement (stretching, dynamic yoga, and mindful walking), mindful meditation exercises, and breathing techniques (Corazon et al., 2018a; Poulsen et al., 2016; Sidenius et al., 2017a, 2017b). Similarly, there are several methods of nature incorporation where nature is used as a tool for the creation of nature-related stories, symbols, and the here-and-now sensory experiences in nature (Corazon et al., 2010, 2018b). Through these means, engagement with nature encourages reflective attitudes and can “create a bridge of parallels between the processes in nature and the patient’s own life situation, thereby evoking acceptance, understanding, and positive change” (Corazon et al., 2010, p. 41), which are all central to mindfulness.

Nature-based rehabilitation (NBR) (Sahlin et al., 2015) also emerged as a subtheme. While the NBR treatment programme differs from NBT, both are developed from environmental psychology and cognitive theories (Sahlin et al., 2015; Stigsdotter et al., 2018) and share similar conceptions and central components.

As with NBT, NBR is based on (1) nature-based activities, and (2) simply being/relaxing in nature, as well as (3) “traditional medical rehabilitation methods” (Sahlin et al., 2015, p. 1930), which refers to the use of therapeutic conversations, methods of facilitating mindfulness, and relaxation techniques (Sahlin et al., 2015). Examples of facilitating mindfulness and incorporating nature are horticultural activities and guided meditations that include conventional mindfulness techniques (Sahlin et al., 2015). Overall, NBR appears to be a valuable NBM therapy practice, but has a limited scientific basis since, as Sahlin et al. (2015) stated, it is still a relatively new approach aiming to address the lack of established rehabilitation interventions for stress-related illnesses.

In summary, this category broadly represents NBM interventions that are specifically designed as a therapeutic programme or intervention with broad therapeutic objectives, and not only a mindfulness intervention. These NBM therapy practices are highly integrative and unique in that their design integrates a variety of different methods, techniques, and ways of nature incorporation to facilitate mindfulness.

Theme 4: Emerging Practice

Several promising NBM interventions have emerged relatively recently. Although not yet well-established or widely used, these interventions seem to be attracting increasing attention in NBM research and practice, and thus, offer potentially effective and innovative approaches within clinical and non-clinical contexts. Among these emerging interventions, the review identified two main practices, including (1) virtual reality and (2) guided imagery.

Virtual reality (VR) simulates reality through virtual technological innovation (Rozmi et al., 2020). These simulations represent an environment or object as if it were real. The application of VR simulations is diverse, such as using flat screen displays and other 2D visualization technologies (Abdullah et al., 2021), 3D mobile-based virtual reality with a game-like design (Rozmi et al., 2020), video recordings (Wang et al., 2019) and simple big screen projections (Choe et al., 2020b, 2021).

The current review identified two examples of VR practices that are considered well-developed NBM interventions. These include a game-based VR approach (Rozmi et al., 2020) and an MBSR-based intervention adapted to a VR context (Choe et al., 2020b).

The game-based VR approach uses a 3D game concept (collecting orbs in a virtual forest) that motivates the player to explore the forest, which in turn facilitates mindfulness (Rozmi et al., 2020). This approach focuses on creating an interactive and immersive forest experience (Rozmi et al., 2020). The design ascribes to the views of immersive practices that have been described earlier in that it draws on the practice of mindfully walking in a highly restorative (albeit virtual) nature-based context to facilitate mindfulness (Rozmi et al., 2020).

The MBSR-based intervention adapted to a VR context uses a standardized eight-week MBSR programme, but intentionally integrates it with an immersive VR environment (i.e., woodland simulation via pre-recorded projection; Choe et al., 2020b). The design, therefore, is similar to adapted conventional NBM interventions, but uses a virtual representation of nature. The methods that are most commonly used to facilitate mindfulness are breathing exercises, body awareness exercises (such as body scanning), sitting meditation, and mindful movement (Choe et al., 2020b).

The VR practices identified in this review focused extensively on design considerations, with a particular emphasis on incorporating small elements that can have a significant effect on the realism and immersive quality of VR NBM interventions. For example, it appears that 3D VR simulations of nature-based contexts offer greater realism (Wang et al., 2019) and are more immersive compared to 2D simulations (Abdullah et al., 2021). Similarly, the greater the sensory stimuli (concerned with visual and auditory sensory domains), the greater the immersive appeal (Abdullah et al., 2021). These design considerations aim to enhance the methods of nature incorporation that facilitate mindfulness.

Guided imagery (GI), the second subtheme, involves guidance and facilitation by a therapist/instructor through a pre-defined script to generate internal images of a natural environment (Nguyen & Brymer, 2018) to facilitate a state of mindfulness. In the context of NBM interventions, nature-based guided imagery is a tool to guide the individual towards imagining (i.e., creating an internal image) his/her preferred nature-based context (Nguyen & Brymer, 2018). Nature-based guided imagery incorporates suggestive relaxation cues while visualizing this restorative environment, which potentially facilitates mindfulness (Nguyen & Brymer, 2018).

Given that only one article was identified on this topic among the 203 full-text articles assessed for eligibility (Fig. 1; PRISMA flow chart), information in this area remains sparse. While GI is a well-defined practice in the therapeutic space, it has not yet received explicit attention as an NBM intervention. Despite this, from the reviewed article it does appear that trait mindfulness influences the effectiveness of GI, since trait mindfulness moderates the capacity to achieve a mindful state (Nguyen & Brymer, 2018). This presents a possible area for future research attention.

Overall, the effect of urbanization leading to decreased access to natural environments seems to be a significant driver behind the rapid development of these emerging practices (Nguyen & Brymer, 2018; Rozmi et al., 2020; Abdullah et al., 2021). By such means, individuals who normally cannot access green spaces are provided the opportunity to experience natural simulated environments (Abdullah et al., 2021) and their associated benefits, which could include an increased state of mindfulness. Taken together, this theme represents a group of NBM interventions that are not yet fully established but show promising innovative solutions that address the effects of urbanization.

Research Objective 2: NBM Environmental Conditions

The second research objective focused on the environmental conditions typically associated with NBM interventions. The review of relevant studies reflected that the nature-based contexts used within NBM interventions are highly heterogeneous and diverse in terms of vegetation, landscapes, climates, and seasonal periods. Within this diversity, three main themes emerged, each representing a broad category of environmental conditions used in NBM interventions. These include (1) naturally occurring environments, (2) curated natural environments, and (3) simulated natural environments. Figure 3 provides a visual depiction of the identified themes and subthemes.

Theme 1: Naturally Occurring Environment

This first category represents pre-existing natural spaces that are used for NBM interventions. These environments are not designed, manipulated, or influenced. The naturally occurring environments that are used for NMB interventions are diverse and include terrestrial (land-based) as well as aquatic (water-based) ecosystems. They consist of different biotic (i.e., living factors such as vegetation and animals) and abiotic (i.e., non-living factors such as water and temperature) elements that combine to form various unique environments. The natural environments identified are (1) immersive terrestrial environments, (2) immersive semi-aquatic environments, (3) non-immersive terrestrial environments, and (4) animal environments.

From the review, NBM interventions mostly used immersive terrestrial environments. Examples of such environments include forests and woodlands. These environments share similar characteristics, such as an abundance of vegetation and diversity of biotic and abiotic elements that have the potential to engulf the individual and to elicit an immersive experience (Ambrose-Oji, 2013). Because they have the potential to remove a person from life's stressors (Clarke et al., 2021), these immersive environments create ideal conditions for NBM interventions. Their immersive quality enhances restorative potential, since “by engaging with the forested environment through the senses, attentional focus is shifted away from cognitions and emotions, to encourage engagement with nature” (Clarke et al., 2021, p. 9). Thus, these environments support the capacity to be fully present in the here-and-now, which is an essential element of mindfulness (Ambrose-Oji, 2013).

Immersive semi-aquatic environments represent part-terrestrial and part-aquatic environments. Of the 203 full-text articles assessed for eligibility (Fig. 1), only one article featured the use of such a semi-aquatic immersive environment, and more specifically a wetland. Wetlands are immersive semi-aquatic environments characterized by rich and abundant vegetation that can instil a sense of peace and quiet, and of “being connected to something bigger than themselves” (Maund et al., 2019., p. 9). The increased experience of meaning and connection to nature, and of removal of an individual from life's stressors, is considered essential to achieving a state of mindfulness (Maund et al., 2019).

The third type of naturally occurring environment is open landscape terrestrial environments. Open landscapes can consist of vegetation that is either rich in biodiversity or quite monotonous, such as fynbos or grasslands. However, this review only identified one open landscape (i.e., grasslands), which is typically characterized as monotonous in biotic and abiotic features, with vast open vistas. Despite the monotony, these environments are thought to create a sense of freedom and enhance a sense of clarity and a relaxed state of mind (Burgon, 2013), which facilitate mindfulness.

The fourth environment used in NBM interventions—animal environments—which was also only identified once in the review, incorporates nature-based contexts that focus on the animal kingdom to facilitate mindfulness. From the article, it seems that interacting with animals is used to facilitate mindfulness by improving self-awareness or encouraging a state of mental stillness/calmness (Burgon, 2013). For example, in equine-assisted therapy participants are encouraged to build a relationship with a horse, which requires them to mimic the horse’s state of calmness through an increased awareness of their body language and emotional regulation (Burgon, 2013). This concerted effort to build a relationship with the animal therefore develops mindfulness skills, such as a non-judgmental acceptance of the present experiences and an increased awareness of one’s body or behaviours (Burgon, 2013).

Theme 2: Curated Natural Environment

This theme describes manipulated environments that have been designed to resemble a natural space. Curated environments that are commonly used for NBM interventions were found to be either (1) purposefully curated spaces, or (2) existing curated spaces used for NBM interventions. NBM interventions use these environments as restorative green spaces (Lymeus et al., 2019; Sidenius et al., 2017b; Vujcic et al., 2017).

Purposefully curated spaces are nature-based contexts specifically designed or manipulated for the NBM intervention. A prominent example of such an environment is Nacadia, also known as the Healing Forest Garden Nacadia (Corazon et al., 2010). Nacadia is an evidence-based garden created to cultivate a sense of safety, serenity, and mental peace (Corazon et al., 2018b; Sidenius et al., 2017b). The design therefore aims to create different spaces, such as immersive and sensory-rich spaces, to optimally facilitate restorative processes and a mindful state (Corazon et al., 2018b; Poulsen et al., 2016; Sidenius et al., 2017b). Overall, however, the review suggests that these purposefully curated spaces feature much less prominently than existing curated spaces used for therapeutic purposes.

Existing curated spaces differ from intentionally curated spaces in that they are not designed primarily for intervention purposes, but are identified and used as adequate contexts for facilitating mindfulness. Examples identified in this review include public parks (otherwise known as parklands) and botanical gardens (Choe et al., 2020a; Lymeus et al., 2019). Parklands usually include lawns and some surrounding vegetation (trees/shrubs) (Choe et al., 2020a, 2021), as well as additional features such as benches or wooden bridges that may allow for distant views (Choe et al., 2021). These differ from botanical gardens in that botanical gardens are oftentimes more diverse and sensory-rich compared to parklands, and can include aspects such as tropical greenhouses with dense rainforest vegetation or more open areas (Lymeus et al., 2018, 2020).

Although these curated spaces are not specifically designed for therapeutic purposes, these nature-based contexts provide restorative effects and, as with intentionally curated spaces, they have the capacity to support the facilitation of mindfulness in NBM interventions (Choe et al., 2020a, 2021; Lymeus et al., 2018, 2019).

Theme 3: Simulated Natural Environment

The third theme describes environments that aim to recreate different biotic and abiotic factors to artificially simulate natural spaces such as those outlined in Themes 1 and 2. From the review, two innovative means of artificially reproduced natural environments for the sake of facilitating mindfulness were identified, which were (1) virtual environments and (2) imagined environments.

Closely related to the theme emerging practices described above as part of Research Question 1, virtual environments simulate nature-based contexts by different technological means, such as large pre-recorded 2D nature projections (Abdullah et al., 2021; Choe et al., 2020b) or a head-mounted device simulating a 3D environment (Rozmi et al., 2020). Regardless of the technological means used, the goal of these simulations is to provide representations of nature-based contexts to facilitate relaxation (Rozmi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019) and enhance the successful facilitation of mindfulness in NBM interventions (Choe et al., 2020b).

As described with Themes 1 and 2, the most used virtual environments are forest-like environments (including woodlands) that are characterized as immersive and rich in biodiversity (Choe et al., 2020b; Rozmi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). In some cases, adding human-made features (e.g., a platform, bench, or hammock) to the environment encourages a relaxed mental state, further facilitating mindfulness (Wang et al., 2019).

Simulated parklands are another example of virtual environments that emerged from literature, and closely mimics the public park nature-based contexts described in Theme 2. An example of these simulations includes video projections of a green mown lawn with surrounding trees and shrubs, as one would see in an actual parkland (Choe et al., 2020b). However, discussions on the way in which these simulated parkland environments facilitate mindfulness are minimal. Choe et al. (2020b) did not find a significant difference between simulated parklands and woodlands in terms of their effectiveness in facilitating mindfulness. It is thought that while simulated immersive environments (i.e., woodlands or forests) facilitate mindfulness through rich sensory and immersive experiences, simulated parklands facilitate mindfulness by achieving a sense of openness in nature, which is also highly restorative (Choe et al., 2020b).

Information on imagined environments, the second identified means of artificially reproducing nature-based contexts, is limited in this review. Of the 203 full-text articles assessed for eligibility (Fig. 1), only one article featured guided imagery as a means of simulating nature-based contexts. Keeping in mind that this subtheme is reflective of one source only, the use of nature-based guided imagery also seems to rest on a preference for immersive environments (i.e., forest, mountain, and ocean conditions; Nguyen & Brymer, 2018) generally representing biodiverse terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

Both VR and nature-based guided imagery are based on the premise that artificially reproducing a nature-based context through different means of VR technological applications or visualization techniques could hold significant value in terms of the facilitation of mindfulness. While promising, these approaches require further research to develop a solid evidence base as NBM interventions.

Discussion

Research Question 1, which was aimed at identifying what practices and methods are used in NBM interventions, resulted in the generation of four themes: (1) conventional mindfulness practices combined with nature, (2) activity-based practices using nature, (3) NBM therapy practices, and (4) emerging practices. When looking at these categorizations it is clear that NBM interventions exhibit significant diversity and lend themselves to a wide range of therapeutic contexts.

HReST or MBSR-based NBM practices are for instance both conventional practices that are used for the treatment of stress-related difficulties (ReST; Lymeus et al., 2019) or to improve general wellbeing (MBSR; Choe et al., 2020a). NBM interventions such as Shunda or forest therapies are both activity-based practices that have been effectively used for either the treatment of substance-use disorders (Shunda; Russell et al., 2016) or depressive symptoms (forest therapies; Lee et al., 2017). Other examples include using NBT, an NBM therapy practice aimed at improving symptoms of binge eating disorders (Corazon et al., 2018a, 2018b); guided imagery, which falls under emerging practices, to improve anxiety symptoms (Nguyen & Brymer, 2018); and MBSR, adapted to a VR context, also an emerging practice, aimed at improving mental health and wellbeing (Choe et al., 2020b). These are only a few examples of different NBM interventions that apply a variety of methods and practices in different clinical and nonclinical settings. Based on the above, it becomes clear that the diverse methods of facilitating mindfulness and incorporating nature in the different NBM interventions create a flexible and inclusive approach that is suitable for application in a vast range of clinical and nonclinical contexts.

Considering this diversity of practices and methods in multiple contexts, population group suitability is an important factor to consider when determining the potential effectiveness of NBM interventions and their associated practices and methods. This factor was considered in several reviewed studies (see Høegmark et al., 2021; Maund et al., 2019; Russell et al., 2016). For example, MBEs, according to Russell et al. (2016), are regarded as suitable and effective NBM intervention approaches for young adult males suffering from substance-use disorders. Similarly, Høegmark et al. (2021) reported that the predominant use of NBAs to facilitate mindfulness, which is considered a non-traditional therapeutic approach, was particularly effective and suitable for male populations who are more likely to resist traditional pathology-based or treatment-based approaches. One possible reason for this finding is that “nature can be experienced by the participants as a neutral place where they are not constantly reminded that they are engaged in a health course, and they are to a lesser extent reminded that they are sick” (Høegmark et al., 2021, p. 15).

While the review did not explicitly focus on the population group suitability, findings did suggest the possible significance of this factor. Consequently, when considering the use of NBM interventions and the specific methods and practices employed, effectiveness should ideally be evaluated in a population-specific context rather than in a general manner. As such, the question is not so much which practices and methods should be used?, but rather which practices and methods should be used for this specific population?.

The review of practices and methods used in NBM interventions identified multiple forms of nature-based engagement aimed at facilitating mindfulness, including direct, indirect, passive, and active forms of engagement. For example, canoeing is a form of direct and active engagement with nature (Russell et al., 2016), whereas mindful movement in nature is considered indirect and more passive (Choe et al., 2020a; Clarke et al., 2021). During the course of the review, there were no indications that some forms of engagement were necessarily more effective than others in terms of facilitating mindfulness. Instead, the findings indicate that all forms of nature-based engagement (direct, indirect, passive, and active) are potentially suitable to facilitate mindfulness (see Burgon, 2013; Choe et al., 2020a; Clarke et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2020; Lymeus et al., 2019; Russell et al., 2016). Literature supports this conclusion, stating that all forms of nature-based engagement have the capacity to develop a multidirectional relationship between nature and the individual (Meuwese et al., 2021; Stigsdotter et al., 2011), which is important for the facilitation of mindfulness. Therefore, it may be that engagement with nature in any of a variety of different ways positively impacts mindfulness to some degree. This lack of differentiation between specific forms of nature engagement in terms of its effectiveness in facilitating mindfulness, could however be due to the lack of comparative studies on the topic. The effectiveness of using different forms of nature-based engagement to facilitate mindfulness fell outside of the scope of this research, but represents a potentially fruitful avenue for future research.

The second research question, which was aimed at identifying what environmental conditions are typical of NBM interventions, prompted the identification of the following three themes: (1) naturally occurring environments, (2) curated natural environments, and (3) simulated natural environments.

From these themes, it is again clear that a wide range of environmental conditions have the capacity to facilitate mindfulness. Despite differences in the characteristics of the nature-based contexts used, all were reported to have restorative potential and to facilitate a state of mindfulness. For instance, environments characterized as biodiverse, sensory-rich, and secluded, such as wetlands and forests, were reported to offer restorative characteristics that adequately facilitate mindfulness (Clarke et al., 2021; Maund et al., 2019). Similarly, environments that are regarded as less biodiverse and more populated, such as parklands, are likewise capable of facilitating mindfulness (Choe et al., 2020a), as are the virtual environments that were employed in some of the emerging NBM interventions (Choe et al., 2020b).

Findings from existing literature did, however, suggest that individual preference, possibly mediated by one’s mental state, may play a role in how effective different environmental conditions are in eliciting mindfulness (Corazon et al., 2010; Poulsen et al., 2016, 2018). This contention is supported by Poulsen et al. (2016), who found that an individual is likely to “seek a connection between the characteristics of the natural setting in the location of their choice and their mental state” (p. 6). This perceived match between the environment and mental state is a subjective experience that may also change as the intervention progresses, since mental state is considered dynamic and subject to change (Poulsen et al., 2016).

As such, even though all environmental conditions included in the review are reported to have restorative potential and the capacity to facilitate mindfulness, individuals may prefer environments that match their mental state. This matching is necessary to achieve an optimal restorative state, and is referred to as compatibility (Kaplan, 1995), which is defined as “a good fit between a person’s inclinations or goals and what the setting facilitates or encourages” (Herzog et al., 2011b, p. 91). This compatibility between the environment and the individual’s inclination and motivation (and therefore the need at that specific time), increases the perceived support the environment offers (Berto, 2014; Herzog et al., 2011a). Since it is reasonable to assume that most individuals would prefer an environment that is perceived as supportive, compatibility may be a vital consideration when deciding on a particular nature-based context for the facilitation of mindfulness. The potential significance of this in the context of NBM interventions is not a well-researched area. As such, it may be of benefit to better understand whether individuals with certain mental states (i.e., depressive or anxious inclinations) perceive certain environmental conditions as more compatible, and therefore, more supportive. This improved understanding could better inform the choice of environmental conditions, and their associated characteristics, to optimally facilitate mindfulness in NBM interventions.

In this review, forest/woodland environments were the most commonly used to facilitate mindfulness. These immersive and sensory-rich environments are highly restorative and are considered natural healers (Abdullah et al., 2021; Clarke et al., 2021; Poulsen et al., 2016). They embody Kaplan’s (1995) restorative characteristics, offering a sense of being away, fascination, extent, and compatibility. However, the review shows that other environments that may offer similar characteristics and benefits have been largely underrepresented. This is supported by Maund et al. (2019), who point out that wetlands, characterized as biodiverse and sensory-rich, “represent a valuable ecosystem for the promotion of mental health that, to date, has been largely overlooked” (p. 11). To address this neglect, future research could consider exploring the mindfulness-inducing properties and benefits of a diverse range of new and previously overlooked environments, such as alternative nature conservation areas (e.g., bushveld, floral kingdoms, or marine protected areas) that possibly offer similar outcomes in the facilitation of mindfulness. As a benefit of doing so, this field may find greater diversity in NBM contextual applications and improved accessibility due to the greater variety of applicable environmental contexts.

As part of the theme representing simulated environments, nature-based VR simulations emerged as the predominant area of focus (Abdullah et al., 2021; Choe et al., 2020b; Rozmi et al., 2020). More specifically, research has focused on using VR as a potentially innovative solution that addresses, at least in part, issues of accessibility due to increasing rates of urbanization (Abdullah et al., 2021; Rozmi et al., 2020). While not a prominent finding in this review, nature-based guided imagery (GI) also emerged as a method used to simulate natural environments that address the effects of urbanization (Nguyen & Brymer, 2018). In the past, these approaches have been criticized for lacking professional training and for the lack of proper implementation (Sierpina et al., 2007). However, since then new avenues and possibilities for training opportunities have been subjected to scholarly research (Rao & Kemper, 2017), and has contributed to its scientific rigor. Current literature indicates that mindfulness-based guided imagery practices are effective and feasible cost-effective approaches (Bigham et al., 2014; Carroll, 2022).

Despite these favourable views, guided imagery as an NBM intervention seems underutilized, and consequently under-researched, based on the fact that this review only identified one article using nature-based GI (see Nguyen & Brymer, 2018). Given that even simulated environments are regarded as highly restorative and as having the capacity to improve mindfulness (Choe et al., 2021), future studies could focus on developing nature-based GI as an NBM intervention. Nature-based GI may represent a cost-effective means of facilitating mindfulness in the absence of actual natural spaces, while still capitalizing on nature’s restorative benefits. Given that simulated environmental conditions are not bound to the constraints of the physical world, future research could explore novel environments that would be inaccessible in the context of regular NBM interventions. For example, underwater VR environments or aerial VR environments could offer a wider variety of newly accessible environmental conditions and novel avenues for the facilitation of mindfulness that are not restricted by the structures of existing NBM interventions or the physical environments that individuals have access to.

Limitations and Future Research

This review was not without limitations. Firstly, the inclusion criteria were limited to English language peer-reviewed studies. The studies included therefore generally represent perspectives and practices of dominant Western cultures, and possibly do not adequately address, for instance, African or Eastern perspectives. The findings may therefore also be limited in terms of their generalizability. Within these constraints, and in line with the rationale for doing a scoping review, the authors did endeavour to be as inclusive as possible in terms of the themes and subthemes identified in the existing literature. Topics like horticultural practices and animal-assisted practices (interventions within activity-based practices), GI (an intervention within emerging practices), and NBR (an intervention within NBM therapy practices) were therefore included, although they were represented by only a small number of studies. The relative scarcity of information on these aspects could possibly be ascribed to the small number of studies specifically related to these practices, or to the fact that existing studies contain only a tenuous or absent link to mindfulness. Both of these potential limitations offer lacunae that could be addressed in future research.

Overall, this scoping review aimed to provide an integrative understanding of existing NBM interventions by addressing the following two research objectives: (1) to describe what practices and methods typically form part of NBM interventions, and (2) to determine the environmental conditions that are typically associated with NBM interventions. From the included studies (n = 30), a typological scheme for categorizing NBMS was proposed (Fig. 2) in which four main categorizations of NBM interventions were identified, including (1) conventional practices combined with nature, (2) activity-based practices using nature, (3) NBM therapy practices, and (4) emerging practices.

It was found that NBM interventions offer a diversity of non-traditional approaches that are suitable in various clinical and nonclinical contexts. Compared to pathology or treatment-based approaches, these interventions appear to be met with less client resistance. Furthermore, the review suggested areas of research that would enhance evidence-based practice by addressing ways to improve the suitability and effectiveness of various types of NBM interventions. As such, it is proposed that research focuses on population group suitability and individual compatibility with certain types of nature engagement.

In relation to the second research objective, three environmental conditions emerged that characterize the natural contexts within which existing NBM interventions typically take place, including (1) naturally occurring environments, (2) curated natural environments, and (3) simulated natural environments. It was found that all environmental conditions and their associated characteristics offered restorative conditions that effectively contribute to the facilitation of mindfulness. However, focused research is needed to determine whether certain environmental characteristics are perceived as more or less supportive for certain mental states, and to integrate previously overlooked environments to expand on existing NBM interventions and facilitate improved accessibility. Simulated natural environments offer potential alternatives in this regard, which include the development of cost-effective environmental simulations (nature-based GI) and the exploration of novel environments that are not bound to constraints associated with having physical access to natural spaces.

Overall, this review offers a more integrated understanding of the different practices and environments currently used within the existing field of NBM intervention. This could serve as a basis upon which future research can build to address the gaps noted in the discussion, and thereby enhance evidence-based practice.

Data Availability

Data available within the article.

References

Abdullah, S. S., Rambli, D. R. A., Sulaiman, S., Alyan, E., Merienne, F., & Diyana, N. (2021). The impact of virtual nature therapy on stress responses: a systematic qualitative review. Forests, 12(12), 1776. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12121776

Ambrose-Oji, B. (2013). Mindfulness practice in woods and forests: An evidence review. Research Report for The Mersey Forest, Forest Research.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Berto, R. (2014). The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: a literature review on restorativeness. Behavioral Sciences, 4(4), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs4040394

Bigham, E., McDannel, L., Luciano, I., & Salgado-Lopez, G. (2014). Effect of a brief guided imagery on stress. Biofeedback, 42, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-42.1.07

Bragg, R., & Atkins, G. (2016). A review of nature-based interventions for mental health care. Natural England Commissioned Reports, Number 204.

Brien, S. E., Lorenzetti, D. L., Lewis, S., Kennedy, J., & Ghali, W. A. (2010). Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implementation Science, 5, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-2

Burgon, H. (2013). Horses, mindfulness and the natural environment: observations from a qualitative study with at-risk young people participating in therapeutic horsemanship. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 17(2), 51–67.

Capaldi, C. A., Passmore, H.-A., Nisbet, E. K., Zelenski, J. M., & Dopko, R. L. (2015). Flourishing in nature: a review of the benefits of connecting with nature and its application as a wellbeing intervention. International Journal of Wellbeing, 5, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v5i4.1

Carroll, R. C. (2022). Guided imagery: harnessing the power of imagination to combat workplace stress for health care professionals. Journal of Interprofessional Education and Practice, 28, 100518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2022.100518

Choe, E. Y., Jorgensen, A., & Sheffield, D. (2020a). Does a natural environment enhance the effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR)? Examining the mental health and wellbeing, and nature connectedness benefits. Landscape and Urban Planning, 202, 1003886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103886

Choe, E. Y., Jorgensen, A., & Sheffield, D. (2020b). Simulated natural environments bolster the effectiveness of a mindfulness programme: a comparison with a relaxation-based intervention. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 67, 101382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101382

Choe, E. Y., Jorgensen, A., & Sheffield, D. (2021). Examining the effectiveness of mindfulness practice in simulated and actual natural environments: secondary data analysis. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 66, 127414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127414

Clarke, F. J., Kotera, Y., & McEwan, K. (2021). A qualitative study comparing mindfulness and Shinrin-Yoku (forest bathing): practitioners’ perspectives. Sustainability, 13(12), 6761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126761

Corazon, S. S., Stigsdotter, U. K., Jensen, A. G. C., & Nilsson, K. (2010). Development of the nature-based therapy concept for patients with stress-related illness at the Danish Healing Forest Garden Nacadia. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture, 20, 34–51.

Corazon, S. S., Sidenius, U., Vammen, K. S., Klinker, S. E., Stigsdotter, U. K., & Poulsen, D. V. (2018a). The tree is my anchor: a pilot study on the treatment of BED through nature-based therapy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112486

Corazon, S. S., Nyed, P. K., Sidenius, U., Poulsen, D. V., & Stigsdotter, U. K. (2018b). A long-term follow-up of the efficacy of nature-based therapy for adults suffering from stress-related illnesses on levels of healthcare consumption and sick-leave absence: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010137

Davis, D. M., & Hayes, J. A. (2011). What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychotherapy, 48(2), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022062

Dixon-Woods, M., Cavers, D., Agarwal, S., Annadale, E., Arthur, A., Harvey, J., Hsu, R., Katbamna, S., Olsen, R., Smith, L., Riley, R., & Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(35), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35

Djernis, D., Lerstrup, I., Poulsen, D., Stigsdotter, U., Dahlgaard, J., & O’Toole, M. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of nature-based mindfulness: effects of moving mindfulness training into an outdoor natural setting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173202

Ehrich, K., Freeman, G., Richards, S., Robinson, I., & Shepperd, S. (2002). Short report how to do a scoping exercise: continuity of care. Research, Policy and Planning, 20(1), 25–29.

Fromm, E. (1992). The anatomy of human destructiveness. Macmillan.

Gotink, R. A., Meijboom, R., Vernooij, M. W., Smits, M., & Hunink, M. G. (2016). 8-week mindfulness-based stress reduction induces brain changes similar to traditional long-term meditation practice: a systematic review. Brain and Cognition, 108, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2016.07.001

Herzog, T. R., & Strevey, S. J. (2008). Contact with nature, sense of humor, and psychological well-being. Environment and Behavior, 40(6), 747–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916507308524

Herzog, T. R., Hayes, L. J., Applin, R. C., & Weatherly, A. M. (2011a). Incompatibility and mental fatigue. Environment and Behavior, 43(6), 827–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510383242

Herzog, T. R., Hayes, L. J., Applin, R. C., & Weatherly, A. M. (2011b). Compatibility: an experimental demonstration. Environment and Behavior, 43(1), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509351211

Hewitt, P., Watts, C., Hussey, J., Power, K., & Williams, T. (2013). Does a structured gardening programme improve wellbeing in young-onset dementia? A preliminary study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(8), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802213X13757040168270

Høegmark, S., Andersen, T. E., Grahn, P., Mejldal, A., & Roessler, K. K. (2021). The Wildman programme-rehabilitation and reconnection with nature for men with mental or physical health problems-a matched-control study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111465

Hofmann, S. G., & Gómez, A. F. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 40(4), 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.008

Howell, A. J., & Passmore, H.-A. (2013). The nature of happiness: Nature affiliation and mental well-being. In C. L. M. Keyes (Ed.), Mental well-being: International contributions to the study of positive mental health (pp. 231–257). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5195-8_11

Huynh, T., & Torquati, J. C. (2019). Examining connection to nature and mindfulness at promoting psychological well-being. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 66, 101370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101370

Janssen, M., Heerkens, Y., Kuijer, W., Van der Heijden, B., & Engels, J. (2018). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on employees’ mental health: a systematic review. PLoS ONE, 13(1), e0191332. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191332

Johnson, E. G., Davis, E. B., Johnson, J., Pressley, J. D., Sawyer, S., & Spinazzola, J. (2020). The effectiveness of trauma-informed wilderness therapy with adolescents: a pilot study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 12(8), 878–887. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000595

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: a psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Lee, I., Choi, H., Bang, K. S., Kim, S., Song, M., & Lee, B. (2017). Effects of forest therapy on depressive symptoms among adults: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030321

Lee, J., Kim, K. H., Webster, C. S., & Henning, M. A. (2021). The evolution of mindfulness from 1916 to 2019. Mindfulness, 12(8), 1849–1859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01603-x

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Lücke, C., Braumandl, S., Becker, B., Moeller, S., Custal, C., Philipsen, A., & Müller, H. (2019). Effects of nature-based mindfulness training on resilience/symptom load in professionals with high work-related stress-levels: findings from the WIN-Study. Mental Illness, 11(2), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIJ-10-2019-0001

Lumber, R., Richardson, M., & Sheffield, D. (2017). Beyond knowing nature: contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLoS One, 12(5), e0177186. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177186

Lymeus, F., Lindberg, P., & Hartig, T. (2018). Building mindfulness bottom-up: meditation in natural settings supports open monitoring and attention restoration. Consciousness and Cognition, 59, 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2018.01.008

Lymeus, F., Lindberg, P., & Hartig, T. (2019). A natural meditation setting improves compliance with mindfulness training. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 64, 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.05.008

Lymeus, F., Ahrling, M., Apelman, J., Florin, C. M., Nilsson, C., Vincenti, J., Zetterberg, A., Lindberg, P., & Hartig, T. (2020). Mindfulness-Based Restoration Skills Training (ReST) in a natural setting compared to conventional mindfulness training: psychological functioning after a five-week course. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1560. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01560

Marchand, W. R. (2012). Mindfulness-based stress reduction, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and Zen meditation for depression, anxiety, pain, and psychological distress. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 18(4), 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000416014.53215.86

Maund, P. R., Irvine, K. N., Reeves, J., Strong, E., Cromie, R., Dallimer, M., & Davies, Z. G. (2019). Wetlands for wellbeing: piloting a nature-based health intervention for the management of anxiety and depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224413

Mcmahan, E. A., & Estes, D. (2015). The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: a meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10, 507–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.994224

Meuwese, D., van der Voort, N., Dijkstra, K., Krabbendam, L., & Maas, J. (2021). The value of nature during psychotherapy: a qualitative study of client experiences. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 765177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.765177

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097