Abstract

Objectives

Meditation is increasingly popular, and yet studies of meditation-related adverse effects, or experiences of unusual psychological states, have mostly focused on those of extremely unpleasant or pleasant nature, respectively, despite the wide range of possible experiences. We aimed to create an instrument to capture meditation-related experiences of varied intensity and subjective valence.

Method

We collected detailed data from 886 US meditators after screening over 3000 individuals to generate a sample representative of major types of meditation practices and experience levels. Participants answered questions about meditation history, mental health, and 103 meditation-related experiences identified for the development of the Inventory of Meditation Experiences (IME).

Results

Parallel analysis guided the eventual determination of factors; exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis yielded good model-to-data fit on a 30-item, 3-factor version of the scale. The total scale and subscales showed expected correlations with measures of adverse effects, meditation characteristics, and mental health symptoms. Analysis indicated utility in examining experience intensity and valence as potentially distinct or combined features of experiences.

Conclusions

The IME is a psychometrically valid tool that may prove useful to assess a variety of meditation-related experiences that account for both the intensity and subjective valence of those experiences.

Preregistration

While several hypotheses were preregistered (https://osf.io/r8beh/), the present study pertains only to the development and validation of the instrument.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Research suggests that meditation may lead to benefits across several mental and physical health domains in both non-clinical (Galante et al., 2021) and psychiatric (Goldberg et al., 2018) populations. The largest body of research on the impact of meditation exists within the context of mindfulness-based programs (MBPs): secular psychosocial training programs inspired by Buddhist meditation practices (Crane et al., 2017; Kabat-Zinn, 2011). Literature from meditative traditions identifies a wide range of experiences that can arise with meditation practice, from profoundly positive to challenging and potentially harmful. These include experiences of bliss, peace, hallucinations, affective disturbances, somatic, conative, and social changes, and profound changes in self-concept (see, for example, Berkovich-Ohana & Wittmann, 2017; Britton et al., 2021; Dorjee, 2016; Lindahl et al., 2017; Millière et al., 2018; Woods et al., 2023). A near-exclusive focus on the benefits of meditation may preclude a thorough understanding of other possible effects — particularly unexpected, and/or distressing experiences, or those of unusual psychological states (Galante et al., 2023a, b; Lindahl et al., 2017).

The study of unexpected, unusual, and/or distressing meditative experiences often falls within two broad categories: (1) religious, spiritual, or mystical experiences, or (2) adverse effects (Taves, 2020). Within the context of religious, spiritual, or mystical experiences, the focus is commonly on purportedly blissful experiences observed in meditation practices and/or psychoactive drug use (de Deus Pontual et al., 2023; Hanley et al., 2020; Vieten et al., 2018; Zanesco et al., 2023), the latter of which may have important relationships with the former (e.g., Millière et al., 2018). Within the context of adverse effects, the focus is commonly on negative, challenging, and potentially harmful consequences of meditation practice (see, for example, Britton et al., 2021; Farias et al., 2020; Goldberg et al., 2022; Lindahl et al., 2017; Schlosser et al., 2019).

Despite the disparate intensities and valences attributable to experiences within these two contexts, the studied phenomena may be indistinct. In fact, the categorical appraisal of these effects as positive or negative may instead reflect the ways the experiences are queried, the population being studied, and the social and cultural context of the research than the effects themselves (Lindahl et al., 2017, 2020; Taves, 2020). For example, the endorsement of an experience as either a necessary “sign of progress,” desirable or undesirable side effect, or mere distraction may vary between traditions, teachers, and individual meditators (Grabovac, 2015; Lindahl et al., 2020; Lomas et al., 2015).

As stated above, extant instruments of meditation-related experiences are largely designed to assess either a mystical, self-transcendent experience or a psychopathological state or vulnerability (de Deus Pontual et al., 2023; Taves, 2020). A major issue among the former is that such measures rarely distinguish the experience (i.e., contents, intensity) from its appraisal (i.e., valence, impact; Taves, 2020). We make no ontological claims about the nature of conscious experience, noting that it is challenging (by some accounts, impossible) to separate experience from its affective tone (see, for example, Ekman et al., 2005; Gross & Feldman-Barrett, 2011). Instead, we focus on the framing or meaning making of experience that influences how one comes to understand experience in relation to a constructed narrative of experience (see, for example, Bruner, 1991). It is also important to note that momentary appraisal and retrospective appraisal may be quite different, especially when reporting adverse effects (Goldberg et al., 2022). The assessment of adverse effects, however, typically presumes that the endorsement of items is likely to be interpreted as negative and undesired. Extant instruments predominantly assume experiences to be categorically positive or negative by definition, without allowing for the possibility of individual differences in experience. Thus, there is a potentially limited understanding of the varied impacts of meditation practice (positive, neutral, or negative) on meditators.

Another major issue is that there are many different overlapping definitions of meditation-related negative experiences, and incident rates vary considerably depending on how such events are defined. Such variation has important implications for harms monitoring, reflecting a failure to differentiate types of events (deterioration of existing symptoms, emergence of new symptoms, treatment-specific vs. generic symptoms, etc.) and different degrees of potential harm (transient distress to lasting functional impact; see, for example, Britton et al., 2021). As a result of using similar terms to reflect different types of potential harms, incident rates are shown to range from 3.7% for those experiencing adverse effects (among a meta-analysis of MBPs; Farias et al., 2020) to approximately 60–70% for those assessed having unpleasant experiences immediately after an MBP (Baer et al., 2021). It is important, therefore, to consider the various definitions used in the medical literature broadly, the meditation literature specifically, and the implications of these definitions on reporting meditation experiences. The term side effect denotes any unintended effects that result from the intervention. An adverse effect is usually defined as a subjectively unpleasant experience attributed to the intervention (Edwards & Aronson, 2000). An adverse effect is a subjectively unpleasant experience that happened during an intervention but may not be a direct result of the intervention, while an unpleasant experience is a loose way to refer to an experience that may or may not be due to the intervention.

The consequences of any of the aforementioned experiences could range from a transient nuisance to functional impairment with highly variable degrees and durations (see Britton et al., 2021 for a detailed discussion). Without assessing (1) the experience, (2) its interpretation (i.e., valence, significance, etc.), and (3) its functional impact, it is impossible to know the extent to which an event may be harmful to an individual. There is also considerable variation of reported meditation-related experiences due to the disparate range of items used to assess these experiences. It is highly common to ask about adverse effects or undesired experiences with a single question (Cebolla et al., 2017; Pauly et al., 2022; Schlosser et al., 2019). Despite their common use, single-item questionnaires are particularly problematic; rates of adverse effects have been shown to be underestimated by up to 70% using single-item measures (Britton et al., 2021). In a recent cross-sectional study using both the single-item measure and a 10-item self-report checklist to detect adverse effects, 32.26% of participants endorsed a single-item question, whereas 50% of individuals endorsed at least one item of the 10 items (Goldberg et al., 2022). Comparatively, the meditation experiences interview (MedEx-I) queried 44 side effects among 96 participants during a randomized controlled trial of modified mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, identifying an adverse effect rate of 58% (Britton et al., 2021). Single-item queries of unpleasant experiences (that asked about “challenging,” “unwanted,” or “extremely unpleasant” experiences) have estimated prevalence rates ranging from 22.0 to 32.2% (Cebolla et al., 2017; Goldberg et al., 2022; Pauly et al., 2022; Schlosser et al., 2019). However, data from studies with more than one type of assessment (e.g., Britton et al., 2021; Goldberg et al., 2022) indicate the range should likely be 60–70% higher. These observations suggest that more inclusive measures of experiences are necessary.

It is presently difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the incidence rates of meditation-related experiences, as well as their impact (positive or negative) on meditators. New scale development is required to ensure instrument items span the comprehensive range of meditation-related experiences, that the instruments allow for individual differences with respect to valence ratings of these experiences (positive-neutral-negative), and that the instruments permit the implementation of commonly accepted definitions of the experiences.

The present study seeks to address major limitations in the literature by developing a psychometrically valid measure of meditation-related experiences, balanced across positive, neutral, and negative experiences. The measure was designed to have participants report both the intensity and valence of each experience, such that endorsement of unpleasant, unexpected experiences can be identified in alignment with the commonly accepted definition of an adverse effect (Edwards & Aronson, 2000). We enrolled US meditators via the Prolific survey platform. To ensure a broad distribution of meditation experience, we stratified our final sample on meditation type and experience level, per the categories reported in a large-scale nationally representative US survey (National Center for Health Statistics., 2018). We also collected information about characteristics that would help us validate the measure (psychological distress, trauma, tendency towards unusual beliefs and experiences, tendency towards psychotic-like ways of thinking, as well as information about meditation practice history). The present study aimed to develop and validate a measure of meditation-related experiences.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited to a screener survey (part 1) via Prolific. The screener survey helped ascertain eligibility for the main study, which included the following criteria: 18 years or older, resided in the USA, and had experience with meditation. Quotas were implemented to approximate National Health Interview Survey 2017 meditation categories (mindfulness, mantra, spiritual; National Center for Health Statistics., 2018) and balance number of individuals in beginner (0–100 h), intermediate (101–1000 h), or advanced (>1000 h) experience categories.

Procedures

Study data were collected between August and September 2022. After providing informed consent, potential participants completed a pre-screening survey (Part 1) for which they were reimbursed £0.15. As discussed above, the pre-screening survey determined eligibility and match to quotas. If determined to be eligible for the main survey (Part 2), based on real-time efforts to balance meditation type and experience, participants were invited to participate within 24 hr. Sociodemographic, meditation practice, and mental health questions were presented first in a fixed order. Then, participants received IME/MRAES items in different orders, the potential effects of which will be addressed in a separate publication. Participants were reimbursed £3.30 for their time.

Measures

Screener

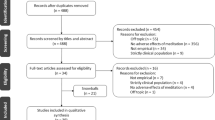

The screener survey included questions regarding engagement in meditation during the past 12 months (yes/no), type of meditation practice per NHIS categories (mindfulness, mantra, spiritual), and lifetime meditation expertise (0–10 h, 11–100 h, 101–500 h, 501–1000 h, 1001–5000 h, > 5000 h). While we recognize that the NHIS categories are somewhat arbitrary, we were aiming to match available nationally representative data (see, for example, Davies et al., 2024). As specified in our pre-registration, quotas were examined in real time to attempt to match meditation type to previous categories, and to balance expertise (beginner, intermediate, advanced). While 3276 responses were recorded during the screener, only 1788 individuals were invited to take part in the main study as a function of eligibility (partially determined by quotas).

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographics

Participants were asked to provide the year they were born, the highest level of education they completed from eight possible categories, and to identify their religious or spiritual beliefs. Prolific provided further demographics including sex, age, first language, current country of residence, nationality, country of birth, student status, and employment status.

Mental Health

Substance Use

We used a modified, shortened version of the Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST; Humeniuk et al., 2010), in which participants were asked about lifetime exposure and past 12-month frequency of substance use. We included nine substance categories: tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, inhalants, sedatives, hallucinogens, and opioids.

Psychedelics Use

If participants indicated lifetime exposure to hallucinogens in the ASSIST question, they were asked to answer a follow-up questionnaire from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016) inquiring about their lifetime classic psychedelic use. The psychedelic drugs inquired about were Ayahuasca, DMT, LSD, Mescaline, PCP, Peyote, Psilocybin, or “Other.”

Psychological Distress

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., 2002) is a 10-item questionnaire measuring psychological distress. Items index symptoms of anxiety and depression over the past 30 days. Responses were made on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (None of the time) to 5 (All of the time). Total scores provide a clinical indication of the presence of low (10–15), moderate (16–21), high (22–29), or very high (30–50) levels of psychological distress, as well as the likelihood of a mental disorder, ranging from likely well (10–19), likely mild mental disorder (20–24), likely moderate mental disorder (25–29), and likely severe mental disorder (30–50). Internal consistency was excellent: α = 0.94, ω = 0.93.

Trauma

The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5; Prins et al., 2016) identifies probable PTSD in primary care settings, with a diagnostic accuracy of 92.7% (95% CI, 89.6–95.9) (Bovin et al., 2021). If indicating lifetime exposure to traumatic events, participants are presented with 5 items measuring past month symptom severity. A total score of 4 or higher was used to indicate probable PTSD.

Unusual Beliefs and Experiences

The Unusual Beliefs and Experiences Subscale of the Personality Inventory of the DSM-5 (PID-UBE; Krueger et al., 2012) comprises 8 items relating to the UBE personality trait facet from the Adult PID-5. UBEs are a common schizotypal characteristic (Crego & Widiger, 2017). Responses were made on a 4-point Likert scale between very false or often false and very true or often true. Responses were averaged to generate a total score. A cut-off of 1.5 standard deviations from normative data was used to indicate likely clinical significance (Miller et al., 2022). Internal consistency was good: α = 0.86, ω = 0.87.

Psychoticism

The Psychoticism Inventory from PID-5 Brief Form (PID-5-BF; Krueger et al., 2012) represents 5 items measuring the personality trait domain of psychoticism in the PID-5-BF. Responses were made on the same 4-point Likert scale as the PID-UBE. Responses were made on a 4-point Likert scale between very false or often false and very true or often true. Responses were averaged to generate a total score and a cut-off of 1.5 standard deviations from normative data was used to indicate likely clinical significance (Miller et al., 2022). Internal consistency was acceptable: α = 0.78, ω = 0.79.

Meditation History

Meditation Practice Background

In addition to the NHIS 2017 meditation categories and lifetime experience categories reported in the screener (to manage quotas), participants were asked further meditation practice questions. For a more detailed lifetime hours calculation, participants were asked to provide years and months of regular practice, the average number of weekly meditations, and the approximate length of each session. Lifetime hours were calculated as a multiplier of regular years of practice, weekly frequency, and approximate length (see, for example, Bowles et al., 2022), adjusting each variable by winsorization (Wilcox, 2017), where it exceeded 3.29 standard deviations from the mean. Participants were also asked the total number of days they had spent on retreat, if their practice was aligned to a spiritual tradition, the context of their meditation (e.g., unguided, guided by an app), which (if any) meditation apps they used for practice, and whether they predominantly meditated alone or with others. They were also asked to select from among a list of 14 meditation techniques (Matko et al., 2021) that best characterized their practice. They were also asked to identify the extent to which various reasons (e.g., dealing with mental health challenges, self-improvement, spiritual growth) had motivated their engagement in meditation over the past 12 months.

Meditation-Related Experiences

Inventory of Meditation Experiences

To assess a broad range of meditation-related experiences, we combined items from a variety of pre-existing scales. We did this as we were unable to identify a single measure that reflected the broad range of experiences and permitted the separation of experience types from appraisal. The initial Inventory of Meditation Experiences (IME) item pool contained over 250 items and was generated by reviewing and collating existing measures of (1) mystical experiences (see, for example, Hanley et al., 2018; Hood, 1975; MacLean et al., 2012; Nour et al., 2016; Pahnke, 1969); (2) anomalous experiences (see, for example, Galante, Montero-Marin, et al., 2023; Irwin, 2015; Lange et al., 2000; Studerus et al., 2010; Taves et al., 2023); (3) meditation-related adverse effects including the 10-item Meditation-Related Adverse Experiences Scale — Mindfulness-Based Practice (MRAES; Britton et al., 2018); and (4) other contemplative experiences including 59 experiences documented in the Varieties of Contemplative Experience Codebook (Lindahl et al., 2017). For a full list of scales reviewed, see Table S1 (Supplementary Information). New items were generated to fill theoretical and valence-related gaps in the initial item pool. Following item generation, authors removed or combined repetitive and irrelevant items resulting in a final pool of 103 items, often slightly modified from their original form. While a pilot of these items would have been useful, our primary initial purpose per the pre-registration was not scale generation; we only proceeded with psychometric analyses upon the realization that (a) primary hypothesis testing (incidence and predictors of AEs) would be improved by psychometric analysis, and (b) such a scale would make a significant contribution to the field. The final 30-item scale is available in the Supplementary Information. The full set of all 103 items and their properties are available as a supplemental file.

Participants recorded the extent to which they had experienced each of the 103 items during or after meditation, prayer, or chanting without any specific temporal frame of reference. The instructions clearly informed participants to only rate items they had experienced as a result of their practice and not due to any other altered state (such as drugs or alcohol). A 6-point Likert scale was presented as follows: 1 — No, not at all; 2 — So slight, cannot decide; 3 — Slight; 4 — Moderate; 5 — Strong; 6 — Extreme.

Items endorsed as Slight (3) or above were further assessed for valence. Participants were asked to rate each item on a 7-point Likert scale: 1 — extremely unpleasant, 2 — modestly unpleasant, 3 — mildly unpleasant, 4 — neutral (neither pleasant nor unpleasant, 5 — mildly pleasant, 6 — modestly pleasant, 7 — extremely pleasant. To reduce participant burden and to ensure comparable completion time across participants, only 50 of the possible 103 items were presented for valence ratings. If participants endorsed more than 50 items, they were asked to assess the valence of a random selection of 50 of the items that they endorsed. If participants endorsed less than 50 items, they were asked to assess the valence of all items they endorsed plus the hypothetical valence (i.e., the valence they anticipate they would feel if they did have the experience) of a random selection of unendorsed items to ensure 50 questions per participant.

Meditation-Related Adverse Effects

To contextualize responses relative to previous estimates (Goldberg et al., 2022), participants were also presented with a slightly modified version of the MRAES (Britton et al., 2018), reflecting the most common disabling symptoms endorsed among a qualitative survey of meditators (Lindahl et al., 2017). The items were slightly adapted from their original form (Britton et al., 2018) to expand upon 3 double-barrelled items (e.g., “I had trouble thinking clearly and/or making decisions”), using the same response format as unusual experiences listed above. Endorsement of any of the 14 items as Slight or greater was interpreted as having had that experience. Note that this is a departure from prior versions of the scale which have used a yes/no response format. The occurrence, severity, and length of functional impairment of adverse effects were then examined in three follow-up questions. Internal consistency was excellent: α = 0.90, ω = 0.90.

Data Analyses

Participants who failed two or more attention checks (from 4 items presented among other measures which instructed the participant to select a particular response option); showed a lack of response variability or excessive response variability; or who were identified as multivariate outliers (i.e., Mahalanobis’ distance equivalent to p < 0.001) were excluded from analyses. Only participants with complete data (with exception of valence ratings) were included in analysis. As a maximum of 50 items were presented to participants for valence rating, selected at random, valence data was presumed to be randomly missing by design. Missing values for valence were estimated via multiple imputation by random forests.

Primary analyses focused on intensity data only; additional exploratory analyses examined intensity and valence. To ascertain number of factors to fit via exploratory factor analysis (EFA), modified parallel analysis (Drasgow & Lissak, 1983; Horn, 1965) was implemented using the nFactors package on the correlation matrix of the full dataset using 5000 randomly generated datasets to identify the 95th percentile. The dataset was split into two (the former twice as large as the latter, to allow for more robust model estimation) to facilitate model generation and confirmation in separate datasets. Model generation was undertaken via iterative EFA and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), implemented on the first dataset, and model confirmation was undertaken via CFA, implemented on the second dataset. EFA was implemented as principal axis factoring with promax rotation using the maximum likelihood estimated via the fa package in R. When a plausible model was identified via EFA, constrained estimation was implemented via CFA using the WLSMV estimator in lavaan, specifying that the data be treated as ordinal. Less than adequate fit resulted in further refinement and additional EFA, until good fit was achieved. Model-to-data fit was assessed using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), Standardized Root-Mean-Squared Residual (SRMR), and Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Fit was compared against recommended criteria: CFI ≥ 0.95, TLI ≥ 0.95, SRMR ≤0.08, RMSEA ≤0.06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). As these criteria are conservative and based on parcel-level factor analysis, we did not adhere to these as strict cut-offs, acknowledging CFI/TLI values ≥ 0.90 to be acceptable (see, for example, Brown, 2006)). Upon achieving good model-to-data fit in the first sample, CFA was fit to the second dataset for independent verification. Final estimates were generated via fitting CFA to the full dataset.

While statistical power calculations are challenging in factor analysis, simulation studies indicate that sample sizes of 300–500 result in adequate power (e.g., 80%) and acceptable type I error rates (≅5 % or less) when using similar analytic methods to those proposed herein, within requirements moving to 1000 participants for extremely non-normal data (Bandalos, 2014). Suggestions for participant to item ratios indicate 10:1 or 20:1 yield the lowest error rates (Costello & Osborne, 2005). With 100 items and extremely skewed data, we would need 1000 participants to meet simulation requirements for power and 10:1 item/participant recommendations. Assuming a reduction in the item pool of at least 50%, n = 500 would result in adequate power. Thus, we aimed for minimum sample of n = 600 to permit separate exploratory and confirmatory analyses (n = 300 each) and up to 1000 to enable adequate power to test the final model in cases of extreme non-normality.

Results

Sociodemographics and Mental Health

We invited 1788 participants to Part 2, of whom 1302 completed the survey (response rate = 72.87%). Two-hundred participants were excluded for failing attention checks, leaving 1102 participants to be screened against additional a priori criteria. A further 216 participants were excluded for the following reasons: 33 took over 63 hr (3832 min; outlier defined as 3rd Quartile + 2 × Interquartile Interval) to complete the survey; 14 reported practicing before the age of 12 years; 9 failed to provide all required data; 1 exhibited an excessively variable response pattern; and 159 were identified as multivariate outliers. The final sample was n = 886.

Participants had a median age of 40, only slightly higher than population median age of 38.88 (U.S. Census Bureau). Participants were 51.35% female (slightly higher than 50.47% in the population; U.S. Census Bureau), and 71.11% non-Hispanic white (aligned with 71% reported in the population: U.S. Census Bureau). Thus, the sample was approximately nationally representative on age, race/ethnicity, and gender. In addition, 60.61% held a bachelor’s degree or higher, and most participants identified as non-religious (45.20%) or Christian (40.34%).

Participants were, on average, moderately distressed, and just below the cut-off for likely mental disorder (Kessler et al., 2002). The sample exhibited a rate of likely mental disorder (42.78%, per K10) that approximately matched self-reported mental health diagnosis (37.47%, Table 1). Rates of Psychoticism as well as Unusual Beliefs and Experiences were aligned with those of community samples (Miller et al., 2022).

Meditation

Deviating from NHIS 2017 data but aligned with recent work (Goldberg et al., 2022), we had mostly mindfulness meditators (52.7%, n = 467), followed by spiritual meditators (35.1%, n = 311), and mantra meditators (12.2%, n = 108). The sample reflected a broad range of meditation experience. Self-selected categories indicated 38.37% beginner practitioners (0–100 hr), 38.83% intermediate practitioners (101–1000 hr), and 22.80% advanced practitioners (>1000 hr), though participants were predominantly intermediate practitioners per estimated lifetime hours of practice (Table S2).

Practice characteristics are shown in Table 2. The median estimated lifetime practice hours were 284, with the middle 50% of the sample having an estimated amount between 111 and 780 hr. The sample, on average, had 8 years of meditation experience and practiced 4.6 times a week for about 22 min per session. Only 28.1% of participants had attended a meditation retreat. Most of the sample (62.5%) engaged in unguided practice, while 19.9% primarily used meditation apps to support their practice.

Meditation-Related Experience Items

The most common response, on average, to any item was that it was not experienced (Fig. 1). While items were, in general, positively skewed, the majority of items were within an acceptable range of normality regarding skewness (96.12% < |3|) and kurtosis (97.09%; < |10|; see Brown, 2006) with an absolute max of 3.68 for skew and 15.06 for kurtosis. Mean valence ratings (provided only for those items endorsed as slight or greater) indicated that 39 items were experienced as neutral, 27 items as negative, and 35 items as positive. While MRAES items were largely perceived as negative (10/14 items rated by ~75% as negative) among those experiencing them, 4 items were rated neutral (per mean). There was substantial variation around mean appraisals (Fig. 1). For example, some participants rated items unpleasant for which the mean rating was pleasant, and vice versa.

Response density by subscale item for experience intensity and valence. Density ridgeline plots generated with a smoothing bandwidth of 0.4. Each line/ridge represents a single item and the height of the curve represents the density of that item. Left panel reflects item-level endorsement of experiences; right panel represents valence ratings for each item among those participants who endorsed the experience as slight or greater. Items are colored by susbcale (yellow, Distortions in self/reality; red, Disabling; green, Enabling)

Factor Analysis

Factor analysis is a multi-step procedure that requires identification of number of factors, extraction via EFA, and model refinement (Costello & Osborne, 2005). Once a model is specified, additional constraints can be imposed via CFA though less than optimal model-to-data fit may require an iterative approach, using both EFA and CFA, to refine the model. Parallel analysis indicated that up to 7 factors had eigenvalues greater than those from the 95th percentile of randomly generated data (eigenvalues: F1, 29.60; F2, 10.71; F3, 4.00; F4, 2.66; F5, 2.24; F6, 1.80; F7, 1.74). The dataset was randomly divided into a large first sample for EFA and a smaller second sample. EFA was performed on the first random sample, exploring k = 1–7. A 3-factor solution was most interpretable, in addition to fitting the data reasonably well. As model-to-data fit was not optimal (per CFA), items with standardized factor loadings < 0.3, communalities higher than 2, or high cross-loadings (≥0.25 on a second factor or less than 2:1 primary to secondary factor loading ratio) were systematically removed. Given the non-normal distribution of the data, CFA using weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) was essential to reliably assess model-to-data fit. The WLSMV estimator is recommended over other popular methods (e.g., maximum likelihood) for ordinal data (Muthén, 1993), and has been shown to perform well under violations of normality (Flora & Curran, 2004). Items were eliminated systematically, and additional CFA was implemented to re-examine fit. As shown in Table 3, an acceptable model-to-data fit was achieved with 3 factors across 54 items. Progressive item elimination was implemented (excluding items with low standardized factor loadings and/or high modification index values) until good model-to-data fit was achieved. The resultant 30-item model fit the data acceptably well in the second sample.

Items from the 30-item scale (hereafter: IME) provided robust factor loadings in the full sample (Table 4). No item loaded on its respective factor < 0.55. The scale and subscales showed excellent reliability in the IME and were classified as enabling experiences (those experiences that contribute to growth/well-being), disabling experiences (those experiences that interfere with function), or distortions in sense of self/reality (those experiences that reflect a distortion in the way one understands oneself or the word; total: α=0.92, Enabling: α=0.91, Disabling: α= 0.91, Distortions in self/reality: α= 0.90). While there were reasonably strong associations between Enabling experiences and Distortions in self/reality (r = 0.476, p < 0.001), Disabling symptoms were unrelated to the former (r = 0.071, p = 0.035) and only modestly related to the latter (r = 0.338, p < 0.001).

Considering that endorsement in the first instance pertains to intensity of experience (wherein endorsement below slight or higher indicates likely absence of the experience), Enabling experiences had the highest mean item endorsement (93.9% endorsed at least 1 item at slight or higher intensity), followed by Distortions in self/reality (65.7% endorsed at least 1 item at slight or higher intensity), with Disabling experiences exhibiting the lowest mean item endorsement (58.4% endorsed at least 1 item at slight or higher intensity). Enabling experiences were, on average, positively valenced, while Disabling experiences were, on average, negatively valenced. Distortions in self/reality were, on average, rated as neutral. While Enabling and Disabling experiences were largely positive and negative, respectively, some proportions of the sample endorsed these experiences as neutral (Fig. 1). Notably, Distortions in self/reality had broadly distributed valence across the full scale. Among IME items, intensity and valence magnitude (i.e., coding mildly as 1, modestly as 2, and extremely as 3, regardless of whether the direction was unpleasant or pleasant) were strongly correlated; the average correlation was r = 0.766 (SD = 0.059; range, 0.565–0.849), all p-values < 0.001. These results indicate that a more intense response typically corresponded with greater valence magnitude (i.e., more pleasant or unpleasant). Modifying the scoring such that scores were a product of intensity × valence (wherein valence ranged from −3 to 3), resulted in good model-to-data fit using the same 30-item model as above, χ2(402) = 1150.35, CFI = 0.951, TLI = 0.947, RMSEA = 0.050 (90% CI, 0.047, 0.054), SRMR = 0.048. These findings should be interpreted with caution, however, given a large number of missing values (due to lack of valence value among those participants who did not endorse an item at a threshold of at least slight or greater).

Convergent/Divergent Validity

To examine whether there was convergence with previously used measures of adverse effects, we examined point-biserial correlations with a single adverse effects (AE) query (I personally have had a challenging, difficult, or distressing experience as a result of my meditation practice), a follow-up question regarding impairment (My meditation-related challenging, difficult, or distressing experiences impaired my ability to function), and modified items from the MRAES (Britton et al., 2018). As shown in Table 5, scores on the newly developed scale and its subscales were significantly associated with AE definitions (except for Enabling items and AE with Impairment). The Disabling subscale showed the strongest associations, while the Enabling subscale showed the weakest associations. As other scales of adverse effects have used a binary response format (yes/no, see Britton et al., 2018), and because decisions of adverse effects must be binary, we also explored possible thresholds for making such a classification. For total score, the threshold that yielded the largest tetrachoric correlation with all three AE definitions was slight intensity and mild unpleasantness (Generic AE, r = 0.48; AE with Impairment, r = 0.39; MRAES, r = 0.84; Table S3).

The total scale and its subscales showed good convergent/divergent validity more generally (Table 5). Only duration (i.e., amount of practice per session) was associated with the total scale score. However, all mental health problem scales were positively associated with the total scale score, indicating increasingly intense unusual experiences were associated with greater mental health issues. Critically, the subscales were differentially related to practice characteristics and mental health. Frequency and lifetime hours were positively associated with Enabling experiences. Duration was associated with Enabling experiences and experiences of Distortions in self and reality. Years of practice was negatively associated with Disabling experiences, indicating those with less practice were more likely to endorse more and more intense Disabling experiences. Psychological distress and PTSD were most associated with Disabling experiences and not associated with Enabling experiences. Psychotic personality and unusual belief tendencies were most associated with experiences of Distortions in self/reality.

Discussion

The aim of the present work was to develop a psychometrically valid measure of meditative experiences of unusual psychological states capturing a range of positive to negative experiences. In a representative sample of 886 US meditators with experience reflecting a range of styles and levels of expertise, we found support for a 3-factor, 30-item version of the Inventory of Meditation Experiences (IME). Model-to-data fits — estimated using the weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted estimator — were good despite the skewed distributions of the responses. Intensity ratings correlated strongly with the magnitude of valence ratings. The factors represented Enabling experiences, Disabling experiences, and Distortions in self and reality, commonly observed domains among examination of unusual experiences in meditators (see, for example, Lindahl et al., 2017; Vieten et al., 2018). The scale showed strong associations with previously used measures of adverse effects (AEs), and results indicated a potential item-level threshold (≥ slight and ≥ mildly unpleasant) for dichotomous classification of AEs. The subscales showed good convergent/divergent validity with meditation experience, mental health, and psychotic-like personality tendencies. Those looking for a briefer way to assess AEs might focus on the 10 Disabling subscale items, noting a limited ability to identify psychotic experiences and unusual beliefs relative to the Distortions in self/reality subscale. The IME is a promising tool to measure the full range of experiences in relation to meditation and related practices and shows sensitivity to identify unusual experiences and potentially adverse effects.

The scale was comprised of three subscales: Enabling experiences, Disabling experiences, and Distortions in self/reality. The items of the Enabling features subscale capture generally beneficial experiences, including some mystical and anomalous experiences. Notably, these experiences were the most commonly endorsed, rated as more intense, and were generally appraised as having a more positive valence. These items were not especially associated with adverse effects and were associated with greater frequency and duration of meditation practice, as well as higher overall levels of meditation experience. The importance of experiences such as these as possible mechanisms of growth has previously been emphasized (see, for example, Vieten et al., 2018). The presence of Enabling items reflects an important balance in capturing a variety of experiences that occur in relation to meditation.

The items of the Disabling features subscale capture mental health and somatic experiences with substantial overlap to one of a limited number of meditation-related adverse effects measures (6/10 concepts from MRAES; Britton et al., 2018). On average, Disabling items were less common (occurring in approximately 20% of individuals) and were generally negative. They were the most predictive of other indicators of adverse effects, and showed strong associations with psychological distress, and psychotic-like personality. The subscale showed smaller positive associations with unusual beliefs and experiences and PTSD symptoms. Interestingly, endorsement of items on this subscale was negatively associated with time (years) engaged in meditation. In other words, those with less meditation experience overall were less likely to endorse these items. One possible explanation is survival bias, wherein those who experience these types of symptoms (given their negative nature) are more likely to discontinue practice, as such, those who persist in practice, on average, are less likely to have had such experiences or to recall them.

The items of the Distortions in self/reality subscale represent changes in one’s concept of self, space, and/or time, as well as some cognitive and perceptual shifts. On average, these items were only slightly more common than Disabling experiences and less common than Enabling experiences. The items of this subscale were largely rated as neutral, though they exhibited the most variance in valence, suggesting that they were potentially of mixed valence (both within and between participants). The Distortions in self/reality were associated with other definitions of adverse effects, though considerably less so than Disabling experiences. Items on the Distortions subscale were positively associated with practice duration (the amount of time dedicated to an individual session). Endorsement of these items was most associated with psychotic-like personality tendencies and unusual beliefs and experiences. The subscale showed modest associations with psychological distress and PTSD.

The scale overall showed significant, positive associations with previously used measures of adverse effects (see, for example, Goldberg et al., 2022). Notably, the Disabling subscale showed some of the strongest associations with AEs, while the Enabling subscale showed some of the weakest associations with AEs (including no association with functional impairment). These results demonstrate that different experiences (i.e., enabling, disabling, distortions in self/reality) are associated with different outcomes among meditators, as indicated by different correlation patterns. Of critical importance, no threshold for indicating an AE is proposed herein. As the commonly accepted definition of an AE is simply that an event is unexpected or unintended and perceived as negative (Edwards & Aronson, 2000), asking about intensity (with slight or greater indicating presence) and valence permits examination of AEs. However, verification requires follow-up work that includes interviews (see, for example, Britton et al., 2021). Only once item endorsement has been compared to interviewer-based classification can any threshold be determined. Nonetheless, all subscales showed some association with self-reported AEs, and there was considerable variability in valence ratings, indicating that idiosyncrasies in the interpretation of meditation experience ought to be considered. Nonetheless, intensity and valence were strongly correlated, and the factor model provided preliminary evidence of model-to-data fit for intensity × valence scores. Future work should investigate scoring that uses some combination of intensity and valence.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite the potential value of the present work, limitations must be acknowledged. Our participants were acquired via an online platform, Prolific, and as such, may not be representative of the broader population of meditators. While we acquired a sample with a relative breadth of practice type and experience amount, participants largely practiced without guidance and had relatively limited retreat experience relative to samples of experienced practitioners (28.1% in the present study vs. 63.5%; Schlosser et al., 2019). Additionally, convergent and divergent validity were assessed against only a limited number of measures, and none focused on unusual or extraordinary experiences. It is worth noting, however, that many measures of unusual or extraordinary experiences have relatively poor psychometric properties (see, for example, de Deus Pontual et al., 2023) and thus, including such measures may not have offered much in the way of robust conclusions. Another potential limitation is that our measure included response items that contained a variable wording format (for example, “I felt…” vs. “A sense that…”). The difference in stem could potentially have created method effects in the psychometric model. The fact that the final solution includes a mix of items with difference stems within each factor somewhat mitigates this concern, but future work should examine potential revision of items and/or method effects models.

Limitations notwithstanding, we are unaware of a psychometrically valid measure of unusual meditation-related experiences that covers the full range of experiences (i.e., negative, neutral, and positive) while also providing the possibility for assessing an experience as an AE. Given the increasing number of people who have tried meditation (over half of all Americans; PEW Religious Landscape Study, 2017), it is critical that there is an active means to assess people’s experiences that is not solely reflective of symptomatic deterioration (which fails to capture the emergence of novel experiences; see, for example, Van Dam & Galante, 2023) and can capture idiosyncratic responses (i.e., possible negative responses to purportedly positive experiences; possible positive responses to purportedly negative experiences). Current estimates of unusual and adverse effects vary dramatically by the method used to assess them. Rates of unpleasant or adverse effects are highest in systematic queries (see, for example, Baer et al., 2021; Britton et al., 2021), and lowest in non-systematic, passive monitoring (see, for example, Wong et al., 2018), leading to estimates that range from <1% to greater than 70%. Rates of extraordinary (positive) experiences are estimated to be as high as 88% (Vieten et al., 2018). Commonly used, single-item queries of unexpected, unpleasant, adverse, or challenging experiences yield estimates of 20–25% (see, for example, Cebolla et al., 2017; Schlosser et al., 2019), though systematic examination suggests that such approaches (vs. systematic interview) yield higher rates of false negative than true negative outcomes (see, for example, Britton et al., 2021). The strong psychometric properties of the IME indicate a valid measure that fills a critical gap in the literature towards more robust assessment of meditation-related experiences in practice and a better estimate of prevalence rates.

Data Availability

Datasets and materials related to this study will be made available on the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/3mn9y.

References

Anderson, K. K., Norman, R., MacDougall, A., Edwards, J., Palaniyappan, L., Lau, C., & Kurdyak, P. (2018). Effectiveness of early psychosis intervention: Comparison of service users and nonusers in population-based health administrative data. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(5), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17050480

Baer, R., Crane, C., Montero-Marin, J., Phillips, A., Taylor, L., Tickell, A., Kuyken, W., & The MYRIAD team. (2021). Frequency of self-reported unpleasant events and harm in a mindfulness-based program in two general population samples. Mindfulness, 12(3), 763–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01547-8

Bandalos, D. L. (2014). Relative performance of categorical diagonally weighted lest squares and robust maximum likelihood estimation. Structural Equation Modelling, 21(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.859510

Berkovich-Ohana, A., & Wittmann, M. (2017). A typology of altered states according to the Consciousness State Space (CSS) model: A special reference to subjective time. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 24(3–4), 37–61.

Bovin, M. J., Kimerling, R., Weathers, F. W., Prins, A., Marx, B. P., Post, E. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2021). Diagnostic accuracy and acceptability of the primary care posttraumatic stress disorder screen for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) among US veterans. JAMA Network Open, 4(2), e2036733. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36733

Bowles, N. I., Davies, J. N., & Van Dam, N. T. (2022). Dose–response relationship of reported lifetime meditation practice with mental health and wellbeing: A cross-sectional study. Mindfulness, 13(10), 2529–2546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01977-6

Britton, W. B., Lindahl, J. R., & Cooper, D. J. (2018). Meditation-related adverse effects scale, mindfulness-based program version (MRAES-MBP). Brown University.

Britton, W. B., Lindahl, J. R., Cooper, D. J., Canby, N. K., & Palitsky, R. (2021). Defining and measuring meditation-related adverse effects in mindfulness-based programs. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(6), 1185–1204. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702621996340

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press.

Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18, 1–21.

Cebolla, A., Demarzo, M., Martins, P., Soler, J., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2017). Unwanted effects: Is there a negative side of meditation? A multicentre survey. PLOS ONE, 12(9), e0183137. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183137

Census Bureau, U. S. (n.d.). 2020 Census Detailed Demographic and Housing Characteristics File A (Detailed DHC-A). U.S. Department of Commerce Retrieved May 3, 2024, from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2023/dec/2020-census-detailed-dhc-a.html

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Retrieved on May 3, 2024 from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2015-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-methodological-summary-and-definitions

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices for exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868

Crane, R. S., Brewer, J., Feldman, C., Kabat-Zinn, J., Santorelli, S., Williams, J. M. G., & Kuyken, W. (2017). What defines mindfulness-based programs? The warp and the weft. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003317

Crego, C., & Widiger, T. A. (2017). The conceptualization and assessment of schizotypal traits: A comparison of the FFSI and PID-5. Journal of Personality Disorders, 31(5), 606–623. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2016_30_270

Davies, J. N., Faschinger, A., Galante, J., & Van Dam, N. T. (2024). Prevalence and 20-year trends in meditation, yoga, guided imagery and progressive relaxation use among US adults from 2002 to 2022. OSF Preprint. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/73q6v

de Deus Pontual, A. A., Senhorini, H. G., Corradi-Webster, C. M., Tófoli, L. F., & Daldegan-Bueno, D. (2023). Systematic review of psychometric instruments used in research with psychedelics. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 55(3), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2022.2079108

Dorjee, D. (2016). Defining contemplative science: The metacognitive self-regulatory capacity of the mind, context of meditation practice and modes of existential awareness. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1788. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01788

Drasgow, F., & Lissak, R. I. (1983). Modified parallel analysis: A procedure for examining the latent dimensionality of dichotomously scored item responses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(3), 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.68.3.363

Edwards, I. R., & Aronson, J. K. (2000). Adverse drug reactions: Definitions, diagnosis, and management. The Lancet, 356(9237), 1255–1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02799-9

Ekman, P., Davidson, R. J., Ricard, M., & Wallance, B. A. (2005). Buddhist and psychological perspectives on emotions and well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00335.x

Farias, M., Maraldi, E., Wallenkampf, K. C., & Lucchetti, G. (2020). Adverse effects in meditation practices and meditation-based therapies: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142(5), 374–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13225

Flora, D. B., & Curran, P. J. (2004). An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods, 9, 466–491. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466

Galante, J., Friedrich, C., Dawson, A. F., Modrego-Alarcón, M., Gebbing, P., Delgado-Suárez, I., Gupta, R., Dean, L., Dalgleish, T., White, I. R., & Jones, P. B. (2021). Mindfulness-based programmes for mental health promotion in adults in nonclinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLOS Medicine, 18(1), e1003481. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003481

Galante, J., Grabovac, A., Wright, M., Ingram, D. M., Van Dam, N. T., Sanguinetti, J. L., Sparby, T., van Lutterveld, R., & Sacchet, M. D. (2023a). A framework for the empirical investigation of mindfulness meditative development. Mindfulness, 14(5), 1054–1067. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02113-8

Galante, J., Montero-Marin, J., Vainre, M., Dufour, G., Garcia-Campayo, J., & Jones, P. B. (2023b). Altered states of consciousness caused by a mindfulness-based programme up to a year later: Results from a randomised controlled trial. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/znh3f

Goldberg, S. B., Lam, S. U., Britton, W. B., & Davidson, R. J. (2022). Prevalence of meditation-related adverse effects in a population-based sample in the United States. Psychotherapy Research, 32(3), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2021.1933646

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011

Grabovac, A. (2015). The stages of insight: Clinical relevance for mindfulness-based interventions. Mindfulness, 6(3), 589–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0294-2

Gross, J. J., & Feldman-Barrett, L. (2011). Emotion generation and emotion regulation: One or two depends on your point of view. Emotion Review, 3, 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073910380974

Hanley, A. W., Dambrun, M., & Garland, E. L. (2020). Effects of mindfulness meditation on self-transcendent states: Perceived body boundaries and spatial frames of reference. Mindfulness, 11(5), 1194–1203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01330-9

Hanley, A. W., Nakamura, Y., & Garland, E. L. (2018). The Nondual Awareness Dimensional Assessment (NADA): New tools to assess nondual traits and states of consciousness occurring within and beyond the context of meditation. Psychological Assessment, 30(12), 1625–1639. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000615

Hood, R. W. (1975). The construction and preliminary validation of a measure of reported mystical experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 14(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/1384454

Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30, 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289447

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Humeniuk, R., Henry-Edwards, S., Ali, R., Monteiro, M., & Poznyak, V. (2010). The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): Manual for use in primary care. World Health Organization.

Irwin, H. J. (2015). Paranormal attributions for anomalous pictures: A validation of the Survey of Anomalous Experiences. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 79(918), 11–17.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2011). Some reflections on the origins of MBSR, skillful means, and the trouble with maps. Contemporary Buddhism, 12, 281–306.

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S.-L. T., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074

Krueger, R. F., Derringer, J., Markon, K. E., Watson, D., & Skodol, A. E. (2012). Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychological Medicine, 42(9), 1879–1890. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711002674

Lange, R., Thalbourne, M. A., Houran, J., & Storm, L. (2000). The Revised Transliminality Scale: Reliability and validity data from a Rasch top-down purification procedure. Consciousness and Cognition, 9(4), 591–617. https://doi.org/10.1006/ccog.2000.0472

Lindahl, J. R., Cooper, D. J., Fisher, N. E., Kirmayer, L. J., & Britton, W. B. (2020). Progress or pathology? Differential diagnosis and intervention criteria for meditation-related challenges: Perspectives from Buddhist meditation teachers and practitioners. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1905. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01905

Lindahl, J. R., Fisher, N. E., Cooper, D. J., Rosen, R. K., & Britton, W. B. (2017). The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists. PLOS ONE, 12(5), e0176239. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176239

Lomas, T., Cartwright, T., Edginton, T., & Ridge, D. (2015). A qualitative analysis of experiential challenges associated with meditation practice. Mindfulness, 6(4), 848–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0329-8

MacLean, K. A., Leoutsakos, J.-M. S., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2012). Factor analysis of the Mystical Experience Questionnaire: A study of experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51(4), 721–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2012.01685.x

Matko, K., Ott, U., & Sedlmeier, P. (2021). What do meditators do when they meditate? Proposing a novel basis for future meditation research. Mindfulness, 12(7), 1791–1811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01641-5

Miller, J. D., Bagby, R. M., Hopwood, C. J., Simms, L. J., & Lynam, D. R. (2022). Normative data for PID-5 domains, facets, and personality disorder composites from a representative sample and comparison to community and clinical samples. Personality Disorders, 13(5), 536–541. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000548

Millière, R., Carhart-Harris, R. L., Roseman, L., Trautwein, F.-M., & Berkovich-Ohana, A. (2018). Psychedelics, meditation, and self-consciousness. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1475. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01475

Muthén, B. (1993). Goodness of fit with categorical and other nonnormal variables. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 205–234). Sage.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2018). National Health Interview Survey, 2017. Public-use data file and documentation. [dataset]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/1997-2018.htm

Nour, M. M., Evans, L., Nutt, D., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2016). Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: Validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 269. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

Pahnke, W. N. (1969). Psychedelic drugs and mystical experience. International Psychiatry Clinics, 5(4), 149–162.

Pauly, L., Bergmann, N., Hahne, I., Pux, S., Hahn, E., Ta, T. M. T., Rapp, M., & Böge, K. (2022). Prevalence, predictors and types of unpleasant and adverse effects of meditation in regular meditators: International cross-sectional study. BJPsych Open, 8(1), e11. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1066

Pew Research Center. (2017). PEW Religious Landscape Study. Retrieved May 3, 2024 from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscape-study/

Prins, A., Bovin, M. J., Smolenski, D. J., Marx, B. P., Kimerling, R., Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A., Kaloupek, D. G., Schnurr, P. P., Kaiser, A. P., Leyva, Y. E., & Tiet, Q. Q. (2016). The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(10), 1206–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5

Schlosser, M., Sparby, T., Vörös, S., Jones, R., & Marchant, N. L. (2019). Unpleasant meditation-related experiences in regular meditators: Prevalence, predictors, and conceptual considerations. PLOS ONE, 14(5), e0216643. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216643

Studerus, E., Gamma, A., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2010). Psychometric evaluation of the Altered States of Consciousness Rating Scale (OAV). PLOS ONE, 5(8), e12412. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012412

Taves, A. (2020). Mystical and other alterations in sense of self: An expanded framework for studying nonordinary experiences. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(3), 669–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619895047

Taves, A., Ihm, E., Wolf, M., Barlev, M., Kinsella, M., & Vyas, M. (2023). The Inventory of Nonordinary Experiences (INOE): Evidence of validity in the United States and India. PLOS ONE, 18(7), e0287780. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287780

Van Dam, N. T., & Galante, J. (2023). Underestimating harm in mindfulness-based stress reduction. Psychological Medicine, 53(1), 292–294. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000447X

Vieten, C., Wahbeh, H., Cahn, B. R., MacLean, K., Estrada, M., Mills, P., Murphy, M., Shapiro, S., Radin, D., Josipovic, Z., Presti, D. E., Sapiro, M., Chozen Bays, J., Russell, P., Vago, D., Travis, F., Walsh, R., & Delorme, A. (2018). Future directions in meditation research: Recommendations for expanding the field of contemplative science. PLOS ONE, 13(11), e0205740. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205740

Wilcox, R. R. (2017). Introduction to robust estimation and hypothesis testing (4th ed.). Academic Press.

Wong, S. Y. S., Chan, J. Y. C., Zhang, D., Lee, E. K. P., & Tsoi, K. K. F. (2018). The safety of mindfulness-based interventions: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1344–1357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0897-0

Woods, T. J., Windt, J. M., Brown, L., Carter, O., & Van Dam, N. T. (2023). Subjective experiences of committed meditators across practices aiming for contentless states. Mindfulness, 14(6), 1457–1478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02145-0

Zanesco, A. P., King, B. G., Conklin, Q. A., & Saron, C. D. (2023). The occurrence of psychologically profound, meaningful, and mystical experiences during a month-long meditation retreat. Mindfulness, 14(3), 606–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02076-w

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions This research was supported by the Contemplative Studies Centre, established by a Philanthropic Gift from the Three Springs Foundation, Pty, Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: NTVD and JT; analysis: NTVD and JT; data curation: NTVD, JT, AB, and JND; writing — original draft: NTVD and JT; writing — review and editing: NTVD, JT, AB, JND, and JG; funding acquisition: NTVD

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study had ethics approval from the University of Melbourne ethics committee. All procedures were performed in accordance with the standards recommended by the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent updates.

Informed Consent

All participants provided informed consent prior to beginning any study procedures.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

No artificial intelligence tools were used to analyze the data or generate/finalize the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 1825 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Dam, N.T., Targett, J., Burger, A. et al. Development and Validation of the Inventory of Meditation Experiences (IME). Mindfulness 15, 1429–1442 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02384-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02384-9