Abstract

Objectives

Positive effects of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) on occupational health have been demonstrated by several systematic review studies during the last two decades. So far, existing reviews excluded mindfulness-informed interventions (MIIs) that build on informal approaches or mixed techniques aiming at improving mindfulness indirectly. To address this research gap, the present comprehensive meta-analysis synthesizes the results of RCTs of MBIs and MIIs conducted in various workplace settings.

Method

A systematic literature search was conducted in five electronic databases complemented by manual search. Random-effects models were used to synthesize standardized mean differences (SMDs) for 25 outcomes and seven overarching categories of outcomes, and to detect various temporal effects. Meta-regressions were run to elucidate average SMDs between mindfulness intervention types and intervention and population characteristics, with the goal of detecting sources of heterogeneity and help guide the selection of the most appropriate mindfulness intervention type.

Results

Based on 91 eligible studies (from 92 publications), including 4927 participants and 4448 controls, the synthesis shows that MBIs and MIIs significantly improve mindfulness (SMD = 0.43; 95%-CI [0.33;0.52]), well-being (SMD = 0.63; 95%-CI [0.34;0.93]), mental health (SMD = 0.67; 95%-CI [0.48;0.86]), stress (SMD = 0.72; 95%-CI [0.54;0.90]), resilience (SMD = 1.06; 95%-CI [−0.22;2.34]), physical health (SMD = 0.45; 95%-CI [0.32;0.59]), and work-related factors (SMD = 0.62; 95%-CI [0.14;1.10]). Sensitivity analyses demonstrate a tendency towards smaller effect sizes due to extreme outliers. Effect sizes are stable in short-term follow-up assessments (1-12 weeks) for most outcomes, but not for long-term follow-up assessments (13-52 weeks). Meta-regressions suggest that observable intervention characteristics (e.g., online delivery) and population characteristics (e.g., age of participants), as well as study quality, do not explain the prevalence of heterogeneity in effect sizes.

Conclusions

Generally effective, mindfulness interventions are a useful tool to enhance aspects of employee health. However, because of heterogeneity and risk of bias, studies aiming at high-quality data collection and thorough reporting are necessary to draw firm conclusions.

Preregistration

A protocol of this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (Registration-No. CRD42020159927).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mind-body interventions are based on the concept that the mind and body are interconnected and mutually influence one another (Esch & Brinkhaus, 2020). These interventions have been found to reduce stress and promote overall health and productivity, often by increasing mindfulness among those who practice them (Esch & Brinkhaus, 2021). Mindfulness is understood as the intentional focus on bodily sensations, emotions, and thoughts, with the aim of developing awareness and nonjudgmental acceptance of these experiences (Grossman, 2015). Mindfulness interventions are gaining popularity in public and private organizations, where employees and leaders are increasingly encouraged to improve their mindfulness levels directly, or indirectly, through a variety of interventions (Vonderlin et al., 2020).

The scientific literature has identified a range of positive outcomes associated with mindfulness practice. For example, improving mindfulness promotes attention regulation, body awareness, emotion regulation, and self-awareness through neurological or neurophysiological changes (Esch, 2014; Hölzel et al., 2011) beyond the well-known reduction of stress. These skills can contribute to, e.g., enhanced well-being and other beneficial resources (Gu et al., 2015). Training in mindfulness can be facilitated through a variety of formal and informal techniques, as well as through programs that combine several exercises. These techniques can be defined as a family of “complex emotion- and attention-regulatory trainings” that are applied to achieve a variety of goals such as the development of well-being and emotional balance (Lutz et al., 2008, p. 163). These techniques, or combinations of techniques, can be categorized as either mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) or mindfulness-informed interventions (MIIs) (Michaelsen et al., 2021). MBIs typically focus on learning or improving mindfulness as the main mechanism of action and involve formal mental exercises, such as breathing meditation or body scan. The particularly well-known “Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction” (MBSR) program developed by Kabat-Zinn (1982), for example, is one of these methods. These formal techniques also influence so-called “informal mindfulness” through training effects established during the course of the program. These training effects include, e.g., increased attention in the present moment, an aspect that is also becoming more and more prevalent in everyday activities (Birtwell et al., 2019). Thus, effects derived from formal mindfulness concepts also increasingly influence informal components (Crane et al., 2014).

MIIs are influenced by the practice and philosophy of mindfulness, as well as other methodologies, that shape programs that are geared towards achieving specific outcomes, such as improving communication skills or physical flexibility (Crane et al., 2017; Griffith et al., 2019). These approaches promote mindfulness indirectly in a variety of ways, for example by means of breathing exercises or mindful movement sequences found in practices like yoga, tai chi, or qigong (Gaiswinkler & Unterrainer, 2016; Shelov et al., 2009). MIIs further include techniques that focus on promoting relaxation, acceptance or communication and do not exclusively utilize mental or formal mindfulness exercises for this purpose (Crane et al., 2017; Esch, 2020). The key difference is that MBIs place greater emphasis on cultivating mindfulness and present-moment awareness, while MIIs use mindfulness practices as one tool among others to achieve specific goals.

The distinction between MBIs and MIIs can be explained by the example of breathing-related exercises. The aforementioned breathing meditation is a mindfulness-based practice that involves focusing one’s attention on the breath, observing the natural flow of the breath and the sensations associated with it, and returning one’s attention to the breath whenever the mind wanders. The aim of breathing meditation is to cultivate present-moment awareness and develop greater concentration and mental clarity. Breathing exercises, on the other hand, are mindfulness-informed practices that may involve focusing on the breath, but are typically more structured and goal-oriented. Breathing exercises often involve specific patterns of inhaling and exhaling, such as deep breathing or alternate nostril breathing, and may be used to achieve specific physiological or psychological effects, such as stress reduction or improving lung functioning. The difference between these two practices is that breathing meditations are primarily focused on developing mindfulness and present-moment awareness, while breathing exercises are primarily focused on achieving specific physical or psychological outcomes. Yet, by engaging in breathing exercises, and its steady focus on the repetitive breathing manipulation, mindfulness can be improved indirectly.

The field of meditation and mindfulness interventions has experienced a rapid expansion in both general and medical contexts, as evidenced by the growing number of intervention studies and reviews (Creswell, 2017). There are a number of systematic reviews on the overall effectiveness of mindfulness programs in general (Eberth & Sedlmeier, 2012; Goyal et al., 2014; Ospina et al., 2007; Querstret et al., 2020), for mental disorders (Sedlmeier et al., 2012; Vancampfort et al., 2021; Virgili, 2015) and for specific medical indications, e.g., chronic pain or breast cancer (Crain et al., 2017; Cramer et al., 2012a, b; Khoo et al., 2019). Systematic literature reviews on specific additional aspects exist, for example demonstrating the effectiveness of mindfulness training or meditation in changing neuronal structures (Fox et al., 2014; Gotink et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2021).

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of mindfulness studies in the work context have demonstrated that both deficit-oriented parameters, such as burnout and depression, as well as resource-oriented parameters, such as job satisfaction and work performance, can be improved through mindfulness-based programs (Bartlett et al., 2019; Lomas et al., 2019; Richardson & Rothstein, 2008; Vonderlin et al., 2020). The evidence varies, however, from review to review and several questions regarding the impact of mindfulness training in the work context remain unanswered. Specifically, it is unclear what aspects, e.g., health, well-being, or work-specific factors, can be improved by which type of mindfulness training. Furthermore, the overall effectiveness has not yet been conclusively clarified, nor have distinct features of interventions, e.g., homework, or the duration of the interventions, been fully evaluated. In addition, existing reviews of mindfulness interventions in workplace settings have focused primarily on mindfulness-based interventions, with relatively little attention given to mindfulness-informed approaches.

Mindfulness interventions can be delivered in various formats, including group-based sessions with face-to-face interaction between trainers and participants, or individual sessions, where a trainer works on a one-on-one basis with an employee. Additionally, both types of teachings can be delivered through digital platforms, e.g., online seminars, webinars, or mindfulness apps. The use of digital formats to promote health and well-being in the workplace has been increasing even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, as evidenced by the growing amount of studies investigating digital formats (e.g., Bostock et al., 2019; Coelhoso et al., 2019; Lilly et al., 2019).

Our present work aims to provide a comprehensive statistical evaluation of a wide body of studies on MBIs and MIIs at the workplace which have been published since the analyses by Ospina et al. (2007, 2008). Due to a strong increase in the number of publications on MBIs in the work context, a renewed analysis is deemed appropriate and timely. In addition, to the best of our awareness, this is the first review to incorporate mindfulness-informed, rather than exclusively mindfulness-based, interventions. Expanding the scope of interventions studied is important, as there are a substantial number of intervention programs conducted in the real world for which there is currently no collective evidence of their effectiveness.

In this review, we pursued four main objectives. Firstly, we aimed to review both mindfulness-based and mindfulness-informed workplace interventions, and to identify their average effect sizes on well-being-, health-, and work-related outcomes. To achieve this objective, we analyzed studies in context of intervention types and outcome categories, and performed meta-regression analyses to provide additional analysis at a medium level of granularity. Secondly, we aimed to investigate the strength of the effects over time by looking at short- and long-term follow-up data. Thirdly, we aimed to identify the potential influence of different delivery modes of workplace mindfulness interventions, including online vs. analogue, and in-group vs. independent practice. Finally, we examined whether specific training characteristics, such as homework and intervention duration, correlate with the strength of the interventions’ effects.

These aspects are particularly relevant when translating research into practice. As outlined above, the last two decades of research on mindfulness interventions demonstrated beneficial effects in various settings. Yet, employers increasingly face the challenge of identifying offers that are both effective and resource-oriented, while also being well-received by employees. Self-guided and homework-based interventions are attractive formats of delivery from an employer’s perspective, but there are concerns that they may overly dilute well-established and proven mindfulness programs. As part of our comprehensive analyses, the present study provides insight into both lines of arguments with concrete practical relevance to employers interested in providing MBIs or MIIs at the workplace.

Method

The reporting of this systematic review and meta-analysis followed the expanded PRISMA checklist 2020 (Page et al., 2021) (see Supplementary Online Material, Table S1.1). As recommended by Cochrane (Lefebvre et al., 2021), all steps of study selection, data extraction and risk of bias assessment were conducted independently by two authors. Conflicts were discussed between the two researchers and unresolved conflicts were solved by a third researcher.

Search Strategy

In order to identify all relevant studies, a systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, PubPsych and PsycInfo, Scopus, and Cochrane CENTRAL in November 2019. The full search strategy can be found in Table S2.1. The following eligibility criteria were defined for the selection of relevant studies: Due to the large number of published studies on mindfulness in the workplace, only studies based on a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design were included in this review. RCTs with all types of control groups were included. Only individually randomized controlled trials were included; i.e., cluster-randomized studies were excluded, in order to increase comparability between study results. Specifically, interventions were required to be based on the central guiding principle of promoting mindfulness, and this had to be clearly recognizable in the description of the study. This means that all intervention descriptions mentioned either the explicit aim of increasing mindfulness or self-awareness (e.g., of bodily sensations, affect, or thoughts), or used mindfulness techniques to achieve other outcomes. Hence, in addition to classical MBSR or meditation interventions, we included interventions which are based on mindfulness-informed practices, such as yoga, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), or breathing exercises. The number or share of hours in the intervention related to mindfulness was irrelevant (as compared to Vonderlin et al., 2020), as long as mindfulness or its functions (e.g., increasing bodily awareness) was mentioned in the description of the intervention. Excluded are studies that examined health promotion on, for example, the basis of positive psychology (e.g., Feicht et al., 2013), but which did not pursue mindfulness as a central guiding principle. These inclusion criteria allow both mindfulness-based and mindfulness-informed interventions to be considered. We included only studies that analyzed mindfulness interventions that were offered in the workplace or initiated by the employing organization, with working adults as the target population. Another requirement for the inclusion of a study was its (online) publication between January 2005 and November 2019 in German or English language peer-reviewed scientific journals. The choice of the start date is based on the search period of the review by Ospina et al. (2007, 2008), which is the first comprehensive review on mindfulness interventions and serves as an important knowledge base for the current review. In addition, the two previous reviews by Bartlett et al. (2019) and Lomas et al. (2019) have not found any workplace mindfulness interventions published before 2005. Supplementary material of retrieved studies was screened for information, and study protocols were downloaded if available. Authors were contacted by e-mail for additional information, such as means (M), standard deviations (SD), and number of participants (N) of intervention and control groups after the intervention, if not available in the authors’ publications. These data were mandatory in order to determine whether studies could be included in the present meta-analysis. Conference abstracts were not included. The Rayyan software (rayyan.ai) was used to collect all search results and to screen titles and abstracts.

Data Extraction

Data extracted from the articles to a central Excel file included name of the intervention (original title), type of control group (active, passive or waiting list), mode of delivery of the mindfulness training, including in-class vs. individual training, online vs. offline, (additional) one-on-one support, the use of additional material, total duration of the intervention in hours and weeks, training location (at the workplace, centralized at a location outside the workplace, location-independent), whether the training took place during or outside working hours, and whether homework was compulsory. In addition, the number of participants per group at different measurement times, the mean age of participants, and the share of female participants were extracted. Furthermore, we extracted the country in which the intervention took place and the occupation of the study population. We noted means and standard deviations of all outcomes and the specific instruments used at all time points, i.e., pre-intervention (before = T0), post-intervention (immediately after the end of the intervention = T1), and all follow-ups. Follow-ups were aggregated into two time periods for analysis, namely 1 to 12 weeks (short-term) and 13 to 52 weeks (long-term). If studies had collected data more than once within these time periods, we chose to include the data referring to the shorter time period in our analysis. Some articles contain intermediate results, i.e., those collected during (e.g., in the middle of) the intervention. These were not extracted for the present study due to limited means of comparability. We also used timing of data collection as a continuous variable to detect the influence of time since the end of the intervention on intervention effectiveness. We analyzed only those outcomes that had been investigated by at least four of the identified studies. This decision on the minimum number of four studies per outcomes is in line with other reviews: Lomas et al. (2019) evaluated results from at least five studies, Bartlett et al. (2019) defined a minimum number of three studies, and Vonderlin et al. (2020) evaluated parameters represented by at least four studies. In this way, a balance is sought between the representation of the versatility of the effects of mindfulness interventions and the individual significance of the outcomes. Aspects examined in only few cases, such as aggression, fatigue, cognition, and various physiological markers, have therefore been omitted. Outcomes are aggregated into broad categories as explained below.

To assess the risk of bias, we calculated a dropout rate based on the reported numbers of observations in the texts. When dropout rates were not provided at all measurement points in the publication, we assumed no drop-outs occurred during the intervention. It is important to acknowledge that some articles contain contradictory information. To address this, we extracted either the most plausible or the most frequently mentioned information. If there was no information available, the gap was marked as “na” (not available).

Outcome Measures

The unexpected high number of studies including more than 400 different instruments (physiological outcomes, questionnaires, VAS, etc.), which were detected in the screening process, required categorization of outcomes. Therefore, all outcome measures were grouped into seven overarching categories with a total of 25 detailed subcategories. These categories are similar to those in Bartlett et al. (2019), and Vonderlin et al. (2020), and are outlined as followed and defined in Table S3.1. (1) Mindfulness is a parameter that is self-assessed through different questionnaires, such as the Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire, (2) Well-being parameters are comprised of self-assessed life satisfaction, relaxation ability/state of relaxation, self-compassion, subjective well-being, and self-efficacy, (3) Mental health parameters were also self-assessed by the participants, and are comprised of subjective information on various aspects of mental risk factors or illnesses, specifically affect, anxiety, burnout, depression, psychological inflexibility, sleep quality/impairment and subjective mental health, (4) Stress is represented by the parameter perceived stress, which is self-assessed though various questionnaires, (5) the parameter Resilience is also measured by different questionnaires, (6) Physical health parameters include both objective physiological factors that were taken by the study team and measure participants’ blood pressure, heart rate and heart rate variability (HRV), as well as subjective parameters including pain, and subjective physical health, (7) Work-related factors are outcomes that are directly related to the work context and include work engagement, absenteeism and productivity; these factors were also self-assessed in the studies included in the present analysis.

A detailed description of the subcategories (Table S3.1), including a list of instruments used and their assignment to outcome categories (Table S3.2), can be found in Supplementary file S3. The process of assigning instruments to (sub-)categories involved subjective assessments by the study team. We aimed to assign outcomes to similar categories as it was previously done in systematic reviews on mindfulness interventions in the workplace. However, previous reviews have not been fully consistent in assigning outcomes to categories. For example, Vonderlin et al. (2020) have assigned the parameters affect and relaxation to the category “well-being and life satisfaction”, and Lomas et al. (2019) have assigned life satisfaction, positive affect and resilience to the category “positive well-being”. As there is no uniform approach in the literature as to how psychological and subjective parameters causally relate to each other, an attempt was made to classify the parameters examined in as much detail as possible and in a way that does justice to the working context, while at the same time allowing for comparison to previous studies.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The Cochrane Collaboration’s risk-of-bias (RoB) tool 2.0 for RCTs was used to assess the potential for selection bias, performing bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and overall bias in the results of the studies analyzed. We included information from study protocols where this information was available. Risk of bias for each study was assessed for the subjective outcomes (such as stress, burnout, and mindfulness). Separate assessments for the objective physiological parameters (blood pressure, heart rate, HRV) were not carried out due to the predominant focus on subjective parameters within the included studies. This has been done similarly in previous reviews, for example in Vonderlin et al. (2020).

Synthesis Methods

The statistical software R was used to conduct the meta-analyses. We calculated Hedges’ g using post-intervention measures (Borenstein et al., 2009). If several instruments or subcategories were reported for one outcome category (e.g., all three subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory), we calculated average mean effects (e.g., total burnout) with appropriate standard errors according to Borenstein et al. (2009) using the agg-Command from package Mad (Version 0.8–2.1). We calculated absolute values of all SMDs after checking for negative results, which we did not detect. The values determined for Hedges’ g were interpreted according to the guidance by Cohen (1988), where |g|= 0.20–0.49 is a small effect, |g|= 0.50–0.79 is a medium size effect, and |g|≥ 0.80 is a large effect. We calculated average SMDs per outcome, averaged over outcome category using random-effects models with the restricted maximum likelihood method using the R package meta (version 4.18–0) and provided Forest plots including prediction intervals. Random-effects models were chosen to account for heterogeneity in the data, which is indicated in the results by I2 and τ2. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method was used to estimate the confidence interval of the average SMD. The aforementioned analyses were conducted for the data referring to post-intervention, short-term follow-up, and long-term follow-up. Linear mixed-effects models were estimated for six of the seven outcome categories based on post-intervention effects using the metafor package (version 2.4–0). There was insufficient data for the outcome “resilience”. These regressions include independent variables for all intervention and population characteristics with less than ten percent of missing data. These are the tri-/dichotomous variables type of control group (active vs. passive vs. wait-list), homework (yes vs. encouraged/no), in-class (yes vs. no), online (yes vs. no), one-on-one (yes vs. no), additional material (yes vs. no), the continuous variables weeks (= duration of intervention), share of female participants, and mean age of participants, as well as a factor variable intervention_s, which encompasses eight values according to the eight types of interventions as described in the “Results” section.

Sensitivity Analysis

Due to notable outliers among effect sizes in almost all outcome categories, we conducted sensitivity analyses in order to check for more plausible overall SMD estimates. For each model, influence analysis was conducted using the dmetar package (version 0.0.9000), which automatically provides leave-one-out analysis as well as influence and Baujat diagnostics as described in Viechtbauer and Cheung (2010). Studies that indicated to distort the average effect size due to strong heterogeneity (based on DIFFITS, Cook’s distance, and the covariance ratio) were excluded in a second set of average effect size calculations of each model using the find.outliers command.

Reporting Bias Assessment

Reporting bias is assessed by funnel plots including Egger’s test (Egger et al., 1997) and p-curves (Simonsohn et al., 2014) also using the dmetar package.

Results

Study Selection

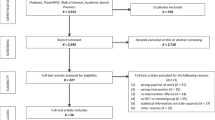

In total, 248 full-texts were read and reviewed, with 92 publications meeting qualification criteria to be included in this present systematic review. We had to exclude a large number of studies due to not meeting the predefined inclusion criteria: for example, year of publication was outside of defined publication range (mainly incorrectly indicated in databases), studies’ research design did not align with preferred study design (mostly study design was not indicated in abstracts) and missing data that could not be retrieved after contacting authors (see PRISMA chart in Fig. 1). One study was excluded, as it contained only outcomes that had been analyzed by less than three other studies. A high interrater reliability (Cohen’s kappa) of κ = 0.98 was achieved based on full-text screening. Some publications contain multiple studies examining different mindfulness interventions. Other studies compare several relevant intervention groups (for example, MBSR vs. yoga vs. passive control group). In these cases, the different study arms were listed and analyzed as separate studies. Thereby, control group sizes were divided by the number of active interventions in order to not inflate standard errors (Rücker et al., 2017). In a few cases, the mindfulness intervention acted as a control group. In these cases, the terms control and intervention group were reversed. If studies reported the results of the same mindfulness intervention for different target groups (for example, employees with high and low stress levels, or men and women), we combined the results and calculated standard errors as suggested in Higgins et al. (2021). In total, the evaluation comprises 91 intervention arms (= studies) from 92 published articles. A list of studies excluded after full-text screening can be found in Supplementary file S4.

Study Characteristics

The mindfulness interventions evaluated in the identified studies were divided into eight different intervention types, each of which can be assigned to either mindfulness-informed or mindfulness-based programs. The latter include MBSR courses, modified MBSR courses, meditation-only courses, and other mindfulness-based programs. Mindfulness-informed interventions include breathing training, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)-based courses, movement-oriented programs (yoga and qigong), and multimodal programs. The latter include, for example, communication, nutrition, and other exercises in addition to mindfulness training.

A total of 9375 working adults (4927 in intervention arms) participated in the included studies. The average intervention group size at the beginning of the studies (T0) was 54 participants, while the control groups consisted of 49 participants, on average. A total of 28 (31%) of the control groups were active control groups. The members of the active control group received another, typically “lighter”, intervention, for example, a flyer about health promotion options at the workplace. A total of 51 control groups were wait-list control groups, and in the other 12 studies, the control groups were passive; i.e., they did not receive any intervention. Average duration of interventions was 9.5 weeks. All included studies and their characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias for each study was assessed for the subjective outcomes (such as stress, burnout, and mindfulness). An interrater reliability (Cohen’s kappa) of κ = 0.84 was achieved. Supplementary file S5 shows the results of the assessment of the risk of bias for all five bias domains. Risk of bias was generally high, except in two studies, as further explained in the “Discussion” section.

Average SMD

Table 2 shows the results of the average SMD calculations for post-intervention measures. Forest plots can be found in Supplementary file S6. Average SMDs were statistically significant for all seven pooled outcome categories. For mindfulness (k = 39, SMD = 0.43, 95%-CI [0.33,0.52], I2 = 98.8%), well-being (k = 35, SMD = 0.63, 95%-CI [0.34,0.93], I2 = 98.9%), mental health (k = 68, SMD = 0.67, 95%-CI [0.48,0.86], I2 = 99.3%), stress (k = 59, SMD = 0.72, 95%-CI [0.54,0.90], I2 = 98.9%), physical health (k = 37, SMD = 0.45, 95%-CI [0.32,0.59], I2 = 99.6%), and work-related factors (k = 29, SMD = 0.62, 95%-CI [0.14,1.10], I2 = 99.1%), we estimated small to medium average effects, which are statistically significant at p < 0.001. For resilience, with a small number of studies (k = 8, SMD = 1.06, 95%-CI [− 0.22,2.34], I2 = 98.8%), we obtained a large average SMD, which was, however, hardly statistically significant. The SMD results in the subcategories are mixed and can be found in Table 2. Small to medium effect sizes were found for life satisfaction (k = 10, SMD = 0.40, 95%-CI [0.15,0.66], I2 = 95.5%), self-compassion (k = 5, SMD = 0.66, 95%-CI [0.18,1.13], I2 = 93.2%), subjective well-being (k = 8, SMD = 0.51, 95%-CI [0.14, 0.89], I2 = 94.0%), affect (k = 14, SMD = 0.93, 95%-CI [0.31, 1.54], I2 = 99.6%), anxiety (k = 23, SMD = 0.53, 95%-CI [0.31,0.74, I2 = 97.8%), burnout (k = 24, SMD = 0.70, 95%-CI [0.33,1.07], I2 = 99.0%), depression (k = 22, SMD = 0.51, 95%-CI [0.29,0.73], I2 = 98.7%), sleep (k = 15, SMD = 0.46, 95%-CI [0.22,0.70], I2 = 98.7%), subjective mental health (k = 15, SMD = 0.60, 95%-CI [0.34,0.85], I2 = 98.7%), heart rate variability (k = 7, SMD = 0.46, 95%-CI [0.15,0.78], I2 = 99.0%), pain (k = 10, SMD = 0.31, 95%-CI [0.11,0.52], I2 = 94.9%), subjective physical health (k = 25, SMD = 0.40, 95%-CI [0.30,0.50], I2 = 96.2%), job satisfaction (k = 20, SMD = 0.47, 95%-CI [0.25,0.68], I2 = 98.6%), and productivity (k = 6, SMD = 0.27, 95%-CI [0.18,0.36], I2 = 40.1%). Smaller or nonsignificant average effect sizes were found for relaxation, self-efficacy, psychological inflexibility, blood pressure, heart rate, absenteeism, and work engagement. The number of these studies, however, has been relatively small (k < 9) compared to the numbers of studies that analyzed the outcomes with small to medium significant effect sizes. Notable is a high level of heterogeneity and large prediction intervals for all outcomes except productivity. In addition, Forest plots showed that some studies have extremely large SMDs, while others have very small effect sizes. Therefore, the average results should be interpreted with caution. Results of sensitivity analyses and meta-regressions are discussed below.

Less than half of the studies analyzed outcomes between 1 and 12 weeks after the end of the intervention (Table 3). For the pooled categories mindfulness (k = 11, SMD = 0.53, 95%-CI [0.27,0.80], I2 = 98.3%), well-being (k = 11, SMD = 0.44, 95%-CI [0.30,0.58], I2 = 93.3%), mental health (k = 16, SMD = 0.56, 95%-CI [0.24,0,87], I2 = 99.2%), stress (k = 17, SMD = 0.61, 95%-CI [0.34,0.89], I2 = 99.1%), and physical health (k = 8, SMD = 0.43, 95%-CI [0.14,0.72], I2 = 91.6%), the average SMDs are statistically significant and of small to medium size. Small to medium average SMDs for the subcategories with at least four studies were found for burnout (k = 10, SMD = 0.43, 95%-CI [0.22,0.64], I2 = 93.5%), subjective mental health (k = 5, SMD = 0.55, 95%-CI [− 0.14,1.24], I2 = 90.0%), and subjective physical health (k = 6, SMD = 0.50, 95%-CI [0.07,0.92], I2 = 92.3%). Nonsignificant effect sizes were obtained for depression, job satisfaction, and pooled work-related factors. Average SMDs for long-term follow-ups could only be estimated for a small set of outcomes as the number of studies collecting data after 13 or more weeks was too small (Table 4). Average SMDs for pooled well-being factors and subjective physical health turned nonsignificant, while pooled mental health factors (k = 4, SMD = 0.21, 95%-CI [0.01,0.40], I2 = 89.4%), stress (k = 5, SMD = 0.50, 95%-CI [0.09,0.92], I2 = 92.6%), and pooled physical health factors (k = 4, SMD = 0.33, 95%-CI [0.13,0.54], I2 = 67.3%) have been found to have small and significant effect sizes. A high level of heterogeneity is also present here.

Sensitivity Analysis

Several studies included in our analysis show extreme outliers, with SMD values exceeding 4 (individual effect sizes are displayed in Supplementary file S6). In all cases, these large SMD values are due to significant differences between treatment and control groups at baseline. Interestingly, these outliers are not limited to small-case studies, but also occur in larger-scale studies, such as Pandya (2019) and Żołnierczyk-Zreda et al. (2016), who each included more than 90 participants in their studies. Because we identified only small variations in risk of bias assessment results, controlling for risk of bias in our estimations of average SMDs was not feasible. However, we performed sensitivity analyses without outliers detected through influence analyses and Baujat plots (Supplementary file S6) for all outcomes. This resulted in smaller SMDs for all pooled outcomes at post-intervention as seen in Tables 2 and 3. For the pooled outcomes mindfulness, well-being, mental health, stress and physical health, average SMDs dropped by 10–20% in size and remained significant; resilience (k = 7, SMD = 0.53, 95%-CI [0.26,0.80], I2 = 89.4%) turned significant. The average SMD of pooled work-related factors dropped by 50%, yet the effect remained small and significant. The average effect sizes of almost all subcategories remained similar in magnitude after removing outliers, and increased for self-compassion (k = 4, SMD = 0.80, 95%-CI [0.50,1.11], I2 = 79.5%), and turned significant for self-efficacy (k = 7, SMD = 0.64, 95%-CI [0.15,1.13], I2 = 98.3%) as well as for blood pressure (k = 6, SMD = 0.22, 95%-CI [0.04,0.40], I2 = 85.4%). Heterogeneity indicators are reduced at least slightly in all cases. Adjusted short-term follow-up effects were relatively similar to post-intervention effects. Only the average SMD of pooled well-being was rendered nonsignificant, while average SMDs for job satisfaction (k = 5, SMD = 0.25, 95%-CI [0.16,0.34], I2 = 60.8%) and work-related factors in general (k = 8, SMD = 0.26, 95%-CI [0.17,0.34], I2 = 50.7%) turned significant albeit small. There were no outliers in long-term follow-up studies.

Reporting Bias

Based on Egger’s tests and p-curves, we did not detect reporting bias, except for the category of well-being outcomes at post-intervention and long-term follow-up. These specific results can also be found in Supplementary file S6.

Meta-Regression Results

In total, six meta-regressions were run including the moderators for which there were less than 5% missing values (Table 5). For mindfulness, the moderators explained no amount of heterogeneity in effects sizes (R2 = 0.00), while for well-being, mental health, stress, physical health, and work-related factors, 47.77%, 43.14%, 14.75%, 44.45%, and 4.49% could be explained by the included moderators. The regressions show that MBSR interventions are more effective than ACT-related interventions, modified MBSR-courses, other mindfulness-based interventions, and multimodal interventions for well-being (b = 1.9, p < 0.001), and more effective than all other types of interventions for mental health (b = 3.23, p < 0.001). For physical health outcomes, MBSR-interventions are slightly more effective than ACT-related interventions (b = 0.37, p < 0.05) but not more effective than other types. Instead, meditation courses are more effective than all other interventions in improving physical health (b = 1.21, p < 0.001), except breathing interventions. Meditation interventions are relatively more effective than ACT-based interventions for mental health outcomes (b = 0.91, p < 0.01), and multimodal interventions are relatively more effective than ACT-based interventions for mental health outcomes (b = 0.88, p < 0.01). While these results point to an overall greater effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions over mindfulness-informed interventions, a separate analysis where these two groups of interventions were compared against each other, did not reveal such evidence. Instead, based on these findings, it can be concluded that certain types of interventions seem more effective for achieving some outcomes than others, but there is no systematic superiority by either mindfulness-based or mindfulness-informed interventions. Only MBSR courses seem to be more effective when compared to other types of interventions.

Among all included intervention characteristics, (additional) one-on-one sessions seem to increase effect sizes for well-being (b = 1.48, p < 0.05) and mental health outcomes (b = 0.43, p < 0.05). For mental health outcomes, in-class interventions seem to generate larger effect sizes (b = 0.56, p < 0.01). For physical health outcomes, some degree of heterogeneity can be explained by variations in effect sizes by type of control group, suggesting that studies with wait-list control groups provide larger effect sizes than studies with active control groups (b = 0.39, p < 0.01). For the outcome stress, studies with passive control groups provide on average larger effect sizes (b = 0.85, p < 0.05) than studies with active control groups. Interventions with homework seem to generate slightly smaller effect sizes for mental health outcomes (b = − 0.31, p < 0.05) than interventions in which there is no obligatory homework. Effect sizes of mental health outcomes decrease with increasing intervention length (b = − 0.04, p < 0.001). Finally, effect sizes of mental health outcomes (b = 0.01, p < 0.001) and stress (b = 0.01, p < 0.01) increase with a larger share of female participants.

The results further suggest that online interventions are just as effective as analogue interventions and that additional material provided for self-practice has no impact on effect sizes. Regressions were also conducted for all outcome groups with risk of bias domains and separately with measurement instruments (e.g., for mindfulness, Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale). Neither differences in risk of bias assessments nor variations by measurement instrument explained heterogeneity in effect sizes.

Due to the limited number of studies performing short-term and long-term follow-ups, meta-regressions could not be conducted beyond post-intervention time points. However, a continuous time variable was included in regressions for all outcomes to detect the potential rate of depreciation of effect sizes over time. The continuous time variable provided no significant results for any of these outcomes.

Discussion

Based on 91 eligible studies (from 92 publications), including 4927 participants and 4448 controls, the present synthesis shows that MBIs and MIIs significantly improve all seven overarching outcome categories. For mindfulness, stress, well-being outcomes, mental and physical health, and work-related outcomes, average effect sizes were small to medium, and large for resilience. Analyses of sub-categories revealed that MBIs and MIIs positively influence life satisfaction, self-compassion, subjective well-being, affect, anxiety, burnout, depression, sleep, subjective mental health, heart rate variability, pain, subjective physical health, job satisfaction, and productivity on average to a small to medium extent. Smaller or nonsignificant average effect sizes were found for relaxation, self-efficacy, psychological inflexibility, blood pressure, heart rate, absenteeism, and work engagement. Average SMDs at short-term follow-ups for the broad categories mindfulness, well-being, mental health, stress, and physical health remain statistically significant and of small to medium size. Small to medium average SMDs for the subcategories with at least four studies were found for burnout, subjective mental health, and subjective physical health. Nonsignificant effect sizes were obtained for depression, job satisfaction, and the overarching category work-related factors. Average SMDs in long-term follow-ups turned nonsignificant for well-being, subjective mental health, and work-related factors, while for mental health, stress and physical health, average effect sizes are small and marginally significant. Sensitivity analyses point mainly towards smaller effect sizes due to extremely high outliers. For the pooled categories mindfulness, well-being, mental health, stress and physical health, average SMDs dropped by 10-20% in size and remained significant. Dropping outliers from the model turned average effect sizes of self-efficacy and resilience to medium size and significant. The average SMD of work-related factors dropped by 50%, yet remained small and significant. The average effect sizes of almost all subcategories remained similar in magnitude after removing outliers, and increased to a large effect for self-compassion. The results of the original analyses indicate substantial heterogeneity, which is somewhat mitigated after the removal of outliers.

Several aspects of the studies may have contributed to heterogeneity. Firstly, variations in study design, including the type of intervention (e.g., MBSR vs. breathing intervention), intervention setting (e.g., group vs. individual), the duration of the intervention, and the type of control group (e.g., active control group vs. wait-list control group), may impact the results. Secondly, demographic differences in the populations studied, including factors such as age, gender, and health status, may also impact the results and increase heterogeneity. Thirdly, differences in the outcome measures (e.g., scores containing five questions vs. scores containing 20 questions) utilized may influence effect sizes in mindfulness studies. Finally, variations in the mindfulness intervention itself, such as the frequency and duration of practice and the level of practitioner experience, may also affect the results and contribute to heterogeneity. Many of these aspects have been extracted from the studies, but data are not available for all of these aspects. For example, only 71% of the included studies provided information on trainer qualifications, and this information is difficult to operationalize. Meta-regressions were run including intervention characteristics that were available for at least 90% of studies. Unfortunately, analyses of the available data provide little insight into the sources of heterogeneity. Some differences can be found by intervention type and type of control group. Here, MBSR and meditation courses tend to be more effective on average than most other formats. Studies with passive or wait-list control groups tend to show slightly larger impacts on all outcomes, though only significantly for pooled mental health and stress. For these two outcomes, a higher share of female participants is associated with larger effect sizes. In general, studies with in-class interventions and one-on-one sessions seem more effective for most outcomes, although only significantly for mental health and well-being.

In recent years, a few meta-analyses of RCTs investigating mindfulness interventions at the workplace have been published. This meta-analysis has been informed by Bartlett et al. (2019), Lomas et al. (2019), and Vonderlin et al. (2020), and adds three important features. See Table 6 for an overview of the present review characteristics. Firstly, the present meta-analysis extends the publication period of RCTs to November 2019, and therefore adds one more year to the period investigated by Vonderlin et al. (2020), and three to four years to Bartlett et al. (2019) and Lomas et al. (2019). Only Vonderlin et al. (2020) included two studies published before 2005 (our start date), which analyzed meditation interventions. As our results are generally in-line with Vonderlin et al. (2020), we believe that omitting these two studies in our meta-analysis does not generate a problem in the validation of our findings. Secondly, while target population and setting share similar features (working adults, workplace setting), the definition of interventions with respect to their mindfulness content varies. Lomas et al. (2019, p. 2) include “all forms of MBIs”, which is not further explained in the review. Bartlett et al. (2019) use a less vague inclusion restriction, namely interventions “explicitly described as mindfulness programs”, and Vonderlin et al. (2020, p. 3) include “any type of mindfulness/meditation-based intervention with at least 2 h of training and with mindfulness elements constituting at least 50% of the program”, which is a more precise description of studies. However, despite precise and easily comprehensible, only few studies provide such detailed information on the number of hours dedicated to mindfulness practice or the amount of mindfulness in relation to other topics involved in the training. In fact, we could not find this information in any of the studies selected. Therefore, we elaborated on an inclusion restriction that provided clarity and at the same time feasibility. It allowed to include interventions described as promoting mindfulness and/or self-awareness (bodily sensations, affect, or thoughts). This description considers the definition of mindfulness by Grossman (2015), as it also includes interventions that aim at promoting one of the principles of mindfulness, i.e., increased awareness about bodily sensations, affect or thoughts. The studies included in this review did not necessarily have to teach mindfulness as the core technique but use other forms that promote mindfulness indirectly. We thereby followed the description of the authors of the original studies, rather than following the literature on, for example, the mechanisms of yoga or other interventions (such as Riley & Park, 2015). For example, the yoga-based study by Alexander et al. (2015) is included, as their description contains the goal of enhancing self-awareness and one of their primary outcomes is mindfulness. Our definition allows for a wider interpretation than the one by Vonderlin et al. (2020), yet greater feasibility, and therefore allows to include mindfulness-informed interventions in addition to mindfulness-based interventions. All of the resulting interventions aim to promote mindfulness, while not necessarily being the main technique or mechanism. This inclusion restriction delivered 91 studies, which is more than all other meta-analyses in this area of research and allows for more detailed analyses on both outcome categories and moderators, as well as follow-up data. In general, results are in-line with the results of the aforementioned three meta-analyses. In comparison to Vonderlin et al. (2020), which employed a comprehensive analysis that is most similar to our research, we add novel elements to the analysis in relation to long-term assessments, and differences in moderator analyses, especially by type of intervention. Furthermore, our meta-analysis on workplace mindfulness is the first to include physiological outcomes. Despite the greater number of studies included in our analysis, we have observed similar evidence of heterogeneity and have yet to establish a consistent explanation for the variability among effect sizes. Specifically, our measures of heterogeneity are almost identical to those reported by Vonderlin et al. (2020), whom we used as a reference for our outcome clusters. Bartlett et al. (2019), who assessed very disaggregated SMDs based on the applied mindfulness questionnaires, reported somewhat lower indicators of heterogeneity. Similarly, Lomas et al. (2019) reported slightly lower heterogeneity indicators, albeit still within the medium to high range, as their study employed a more focused aggregation of outcome categories, but analyzed a smaller number of outcomes overall. Hence, the amount of heterogeneity does not appear to depend on the definition of interventions (mindfulness-based only, or also mindfulness-informed), but rather on the level of disaggregation of average SMDs.

Limitations and Future Directions

One of the main limitations of this review is the large heterogeneity in the results for almost all outcomes. With this heterogeneity at hand, the validity of the overall results is limited, as the calculated SMDs do not accurately reflect the combined results of the studies. With substantial heterogeneity, it is challenging to draw reliable conclusions about the overall effectiveness of mindfulness-based and mindfulness-informed interventions. By applying a random effects model, we aimed to mitigate the effect of heterogeneity on SMDs. Nonetheless, the identification of heterogeneity in the included studies suggests that comparability might not be attainable. Our approach to the amalgamation of mindfulness-based and mindfulness-informed interventions is based on the premise that both formal and informal mindfulness practices have the capacity to modify brain function, including amygdala function, which can have a consequential impact on individuals’ daily life beyond the practice of mindfulness per se, as demonstrated by previous research (Gotink et al., 2016; Hölzel et al., 2010; Kral et al., 2018). Hence, it appears reasonable to differentiate between mindfulness-based and mindfulness-informed interventions when the aim is to define their techniques and interventions. However, during the evaluation of the effectiveness of such interventions, this distinction might be extraneous, given that the lived experience of practitioners is not contingent on the type of intervention, but rather on the extent of changes in the brain that arise as a consequence of the practice and are perceived in everyday life (Hölzel & Ott, 2006). Notably, we identified that interventions within the groups of mindfulness-based and mindfulness-informed interventions exhibit heterogeneity, as well as within our eight subgroups. Thus, forthcoming systematic reviews ought to place greater emphasis on the frequency and nature of formal and informal mindfulness practices, and primarily analyze whether mindfulness has been improved as a result of the intervention. Additionally, future reviews should focus on specific techniques (e.g., body scan, alternate nostril breathing, mindful eating, yoga asana) instead of multi-component interventions. A cut-off point could be established to delineate which interventions effectively enhance mindfulness, and only these could be deemed as mindfulness interventions. The secondary outcomes of these more narrowly defined mindfulness interventions, such as reduced burnout risk and improved physiological parameters, could then be evaluated. It is also critical to endeavor to obtain further characteristics of interventions, for instance, by conducting interviews with the corresponding authors of published studies of mindfulness RCTs. These intervention characteristics can then be used to conduct sub- and meta-analyses. In future RCTs on the topic, researchers should use clear and consistent definitions and report as much information as possible when publishing their studies. It would be helpful if a group of researchers developed a comprehensive reporting list for social-psychological RCTs, comparable to the PRISMA checklist for systematic reviews. This checklist should then be obligatory to apply in future RCTs. Furthermore, future research employing RCTs benefits from including a homogeneous population in their study to reduce heterogeneity in meta-analyses. For example, they can limit their study to a specific age group, gender, or health condition (with or without psychological symptoms). This can help ensure that the studies are comparable. Standardized protocols may be one way to achieve more homogenous mindfulness interventions, or single techniques, and therefore more homogenous results across studies. Standardized protocols might have an impact upon effectiveness, as we have found that standardized MBSR interventions were more effective for well-being, mental and physical health outcomes. However, mindfulness is a multifaceted phenomenon that can be trained by various techniques. Also, trainers of mindfulness are diverse in their beliefs about what mindfulness is and how it can be taught.

Another main limitation of the data underlying this systematic review and meta-analysis is the presence of large outliers. Sensitivity analyses show that for some outcomes, results differ considerably when accounting for extreme outliers. These extreme outliers can be traced back to differences between outcome measures before intervention even in large group sizes, which hints at a poor randomization process.

For almost all studies, we detected a high risk of bias in all domains. In other reviews with psychosocial interventions, the risk of bias is similarly high (Bruin, 2015). The risk assessment here may be considered more conservative as in Vonderlin et al. (2020), as they did not judge the risk for two domains that usually result in high risks: performance bias and detection bias. These were included here, however, because some of the analyzed studies (e.g., Cheema et al., 2013) aimed at solving the problem of blinding staff and participants. In fact, some studies consistently show low to moderate risks of bias for all five domains (e.g., Baby et al., 2019; Dwivedi et al., 2015, 2016). This suggests that it is also possible to obtain robust results in the field of mindfulness intervention research. Especially, we believe that better RoB results can be achieved when study conductors take into account RoB-domains when planning interventions and summarizing findings. Taking into account the RoB assessment in this review, a solid statement on the evidence of the effectiveness of the presented mindfulness interventions on the target parameters is only possible to a limited extent and future research is necessary. As we did not detect any reporting bias, overall results are credible with respect to missing information.

The literature search was limited to the year 2019, which was shortly after the review protocol was published. The time lag between search and publication of results does not seem to influence up-to-datedness; however, as in following mindfulness research, we did not observe any large innovations or outstanding publications that would significantly change overall results.

The amount of publications detected has led to a number of changes compared to the original protocol. Most of them, however, were minor. Two major differences exist: Firstly, we categorized outcomes instead of analyzing each outcome individually. As explained, similarly to previous meta-analyses on the topic (Bartlett et al., 2019; Lomas et al., 2019; Vonderlin et al., 2020), categorizations were made to guarantee comparability of results. Secondly, the large amount of studies included permitted estimation of meta-regressions with the aim of identifying influences on average SMDs by study characteristics or mindfulness intervention types.

As outlined above, risk of bias was generally high. On the other hand, we detected no publication bias, suggesting no considerable lack in diversity of results.

Similarly to previous studies on this topic, the present review is subject to methodological limitations of the investigated RCTs. Generally, we suggest that in future RCTs on the topic, attention should be paid to the following aspects that improve methodological quality and reduce the risks of bias in the results obtained (Michaelsen et al., 2021). Firstly, a study protocol should be published before the start of the study. Secondly, a random number generation algorithm should be applied and the name of the tool should be reported. Thirdly, future RCTs should include sufficiently large study populations. Fourthly, different persons should be appointed for contact with participants and for the review of results. Fifthly, blinding of participants into intervention and control groups to outcome assessors should be guaranteed. Sixthly, it should be aimed for a reduction of drop-out rates and statistical methods to compensate for attrition should be applied. Lastly, study teams should consider implementing possibilities to verify actual exercise time.

Due to a limited number of studies, we are currently unable to draw firm conclusions about the long-term effectiveness. Therefore, we also suggest that future research aims to examine outcomes of occupational MBIs up until twelve months after the end of the intervention as well as include so far rarely investigated aspects, such as resource use and work ability, that also allow conclusions about productivity and efficiency. The latter might be especially relevant for decision making in the business context. Ideally, future publications of RCTs would also report on intervention characteristics, such as dosage and location, as well as information on the organizational environment, e.g., company size and work cultural aspects. Finally, despite no hints of publication bias in this review (in comparison to Bartlett et al., 2019, and Vonderlin et al., 2020), the research community should aim at publishing all results despite negative or null effects.

The findings suggest that policy makers should exercise caution when using these results to inform decision-making, as the variability in outcomes makes it challenging to identify the optimal course of action and allocate resources effectively. It is particularly noteworthy that the present review did not establish the cost-effectiveness of workplace mindfulness interventions, which should be taken into account by policy makers. In the evaluation of cost-effectiveness, various factors must be considered, including absenteeism, incapacity to work, productivity loss, employee turnover, and staff ratios. From the perspective of the healthcare system, the utilization of health care services, such as medical consultations for work-related accidents, is also a crucial indicator. The financial valuation of these factors is subject to variation across the existing literature. In this review, four different research articles (Hartfiel et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2016, 2020; van Dongen et al., 2016) have been included that analyzed distinct cost-effectiveness parameters. However, these studies included different parameters, so that no analysis of these factors was performed.

For business leaders, the results suggest that it is feasible and rewarding to integrate MBIs and MIIs in the workplace because of potentially visible effects on various domains related to mindfulness, physical and mental health parameters, well-being, stress, and work-related aspects. The effects are also sustainable as shown in the short-term and long-term follow-ups. As the populations of employees within the included studies were relatively diverse in terms of professions and sectors, these generally positive results seem to be applicable across various settings. Especially interesting is the finding that digital MBIs and MIIs appear to be as effective as analogue interventions, highlighting its suitability also in home-office contexts, for teams who work in different locations or other complex work environments, or as a cost-saving measure. Also remarkable is the result that post-intervention effectiveness does not seem to depend on the duration of an intervention, except for mental health outcomes.

Despite a general recommendation to implement mindfulness interventions in work settings, the review does not allow to provide specific advices on which specific mindfulness intervention to implement under which circumstances. Especially, certain structural and cultural aspects of an organization, and specific aspects of interventions that could not be captured in our analysis (e.g., size of the company, values of the company, spiritual content of the intervention) could potentially influence the effectiveness. In addition, we were not able to analyze more specific outcomes, such as aggressiveness, creativity or empathy, as well as the cost-effectiveness of MBIs and MIIs, as only few RCTs included relevant measurements. Because of large heterogeneity in the results, practitioners should consider individual factors, such as the general stress level of employees, their health history, and preferences, when making decisions about an intervention.

In conclusion, the present study employed a comprehensive meta-analytical approach to consolidate and synthesize the findings of a considerable number (k = 91) of RCTs that examined the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) and mindfulness-informed interventions (MIIs) in various workplace settings. While the current review substantiates the favorable effects of MBIs and MIIs across all outcomes, it is worth noting that some of the results should be approached with a degree of caution, as certain outcomes may have an overestimated average SMD, as indicated by sensitivity analyses. Nevertheless, despite the stringent exclusion criteria for positive outliers, all the effects remain statistically significant. The decision-makers of organizations must examine which outcomes are relevant to them when determining whether to adopt mindfulness interventions and which intervention to implement, while also considering the results of long-term follow-up studies conducted according to rigorous quality of reporting guidelines. Future systematic reviews could focus on particular mindfulness enhancing techniques and present more in-depth outcomes.

Data Availability

Template of data collection forms, data used for all analyses, and analytic code can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Studies marked with * are included in the synthesis.

*Aikens, K. A., Astin, J., Pelletier, K. R., Levanovich, K., Baase, C. M., Park, Y. Y., & Bodnar, C. M. (2014). Mindfulness goes to work: Impact of an online workplace intervention. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(7), 721–731. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000209

*Alexander, G. K., Rollins, K., Walker, D., Wong, L., & Pennings, J. (2015). Yoga for self-care and burnout prevention among nurses. Workplace Health & Safety, 63(10), 462–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079915596102

*Allexandre, D., Bernstein, A. M., Walker, E., Hunter, J., Roizen, M. F., & Morledge, T. J. (2016). A web-based mindfulness stress management program in a corporate call center: A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the added benefit of onsite group support. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58(3), 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000680

*Amutio, A., Martínez-Taboada, C., Delgado, L. C., Hermosilla, D., & Mozaz, M. J. (2015a). Acceptability and effectiveness of a long-term educational intervention to reduce physicians’ stress-related conditions. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 35(4), 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000002

*Amutio, A., Martínez-Taboada, C., Hermosilla, D., & Delgado, L. C. (2015b). Enhancing relaxation states and positive emotions in physicians through a mindfulness training program: A one-year study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20(6), 720–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2014.986143

*Arredondo, M., Sabaté, M., Valveny, N., Langa, M., Dosantos, R., Moreno, J., & Botella, L. (2017). A mindfulness training program based on brief practices (m-pbi) to reduce stress in the workplace: A randomised controlled pilot study. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 23(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10773525.2017.1386607

*Baby, M., Gale, C., & Swain, N. (2019). A communication skills intervention to minimise patient perpetrated aggression for healthcare support workers in New Zealand: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(1), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12636

*Baccarani, C., Mascherpa, V., & Minozzo, M. (2013). Zen and well-being at the workplace. The TQM Journal, 25(6), 606–624. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-07-2013-0077

*Bartlett, L., Lovell, P., Otahal, P., & Sanderson, K. (2017). Acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy of a workplace mindfulness program for public sector employees: A pilot randomized controlled trial with informant reports. Mindfulness, 8(3), 639–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0643-4

Bartlett, L., Martin, A., Neil, A. L., Memish, K., Otahal, P., Kilpatrick, M., & Sanderson, K. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of workplace mindfulness training randomized controlled trials. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(1), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000146

*Bhandari, R. B. (2017). Yogic intervention for coping with distress. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 12(11), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2017/29332.10944

*Bhandari, R. B., Acharya, B., & Katiyar, V. (2010). Corporate yoga and its implications. In C. T. Lim & J. C. H. Goh (Eds.), IFMBE Proceedings: Vol. 31. 6th World Congress of Biomechanics (WCB 2010). August 1–6, 2010 Singapore: In Conjunction with 14th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering (ICBME) and 5th Asia Pacific Conference on Biomechanics (APBiomech) (pp. 290–293). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-14515-5_75

Birtwell, K., Williams, K., van Marwijk, H., Armitage, C. J., & Sheffield, D. (2019). An exploration of formal and informal mindfulness practice and associations with wellbeing. Mindfulness, 10(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0951-y

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (Eds.). (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470743386

*Bostock, S., Crosswell, A. D., Prather, A. A., & Steptoe, A. (2019). Mindfulness on-the-go: Effects of a mindfulness meditation app on work stress and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(1), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000118

*Brinkborg, H., Michanek, J., Hesser, H., & Berglund, G. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of stress among social workers: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(6–7), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.009

Bruin, M. (2015). Risk of bias in randomised controlled trials of health behaviour change interventions: Evidence, practices and challenges. Psychology & Health, 30(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2014.960653

*Calder Calisi, C. (2017). The effects of the relaxation response on nurses’ level of anxiety, depression, well-being, work-related stress, and confidence to teach patients. Journal of Holistic Nursin: Official Journal of the American Holistic Nurses’ Association, 35(4), 318–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010117719207

*Cheema, B. S., Houridis, A., Busch, L., Raschke-Cheema, V., Melvilee, G. W., Marshall, P. W., Chang, D., Machliss, B., Lonsdale, C., Bowman, J., & Colagiuri, B. (2013). Effect of an office worksite-based yoga program on heart rate variability: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. BioMed Central Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 13(82), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-13-82

*Chin, B., Slutsky, J., Raye, J., & Creswell, J. D. (2019). Mindfulness training reduces stress at work: A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 10(4), 627–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1022-0

*Christopher, M. S., Hunsinger, M., Goerling, L. R. J., Bowen, S., Rogers, B. S., Gross, C. R., Dapolonia, E., & Pruessner, J. C. (2018). Mindfulness-based resilience training to reduce health risk, stress reactivity, and aggression among law enforcement officers: A feasibility and preliminary efficacy trial. Psychiatry Research, 264, 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.059

*Coelhoso, C. C., Tobo, P. R., Lacerda, S. S., Lima, A. H., Barrichello, C. R. C., Amaro, E., & Kozasa, E. H. (2019). A new mental health mobile app for well-being and stress reduction in working women: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(11), e14269. https://doi.org/10.2196/14269

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

*Cook, C. R., Miller, F. G., Fiat, A., Renshaw, T., Frye, M., Joseph, G., & Decano, P. (2017). Promoting secondary teachers’ well-being and intentions to implement evidence-based practices: Randomized evaluation of the achiever resilience curriculum. Psychology in the Schools, 54(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21980

*Crain, T. L., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Roeser, R. W. (2017). Cultivating teacher mindfulness: Effects of a randomized controlled trial on work, home, and sleep outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(2), 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000043

Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Paul, A., & Dobos, G. (2012b). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast cancer-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Oncology, 19(5), e343–e352. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.19.1016

Cramer, H., Haller, H., Lauche, R., & Dobos, G. (2012a). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for low back pain. A systematic review. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 12, 162. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-12-162

Crane, C., Crane, R. S., Eames, C., Fennell, M. J. V., Silverton, S., Williams, J. M. G., & Barnhofer, T. (2014). The effects of amount of home meditation practice in mindfulness based cognitive therapy on hazard of relapse to depression in the staying well after depression trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 63, 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.08.015

Crane, R. S., Brewer, J., Feldman, C., Kabat-Zinn, J., Santorelli, S., Williams, J. M., & Kuyken, W. (2017). What defines mindfulness-based programs? The warp and the weft. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003317

Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139

*Dahl, C. (2019). Warum es sich lohnt, gut für sich zu sorgen. Prävention Und Gesundheitsförderung, 14(1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11553-018-0650-5

*Dahl, C., & Dlugosch, G. E. (2020). Besser leben! Ein Seminar zur Stärkung der Selbstfürsorge von Psychosozialen Fachkräften. Prävention Und Gesundheitsförderung, 15(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11553-019-00735-2

*Duchemin, A.-M., Steinberg, B. A., Marks, D. R., Vanover, K., & Klatt, M. (2015). A small randomized pilot study of a workplace mindfulness-based intervention for surgical intensive care unit personnel: Effects on salivary α-amylase levels. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 57(4), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000371

*Dwivedi, U., Kumari, S., Akhilesh, K. B., & Nagendra, H. R. (2015). Well-being at workplace through mindfulness: Influence of yoga practice on positive affect and aggression. International Quarterly Journal of Research in Ayurveda, 36(4), 375–379. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-8520.190693

*Dwivedi, U., Kumari, S., & Nagendra, H. R. (2016). Effect of yoga practices in reducing counterproductive work behavior and its predictors. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(2), 216–219.

Eberth, J., & Sedlmeier, P. (2012). The effects of mindfulness meditation: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 3(3), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0101-x

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

*Elder, C., Nidich, S., Moriarty, F., & Nidich, R. (2014). Effect of transcendental meditation on employee stress, depression, and burnout: A randomized controlled study. The Permanente Journal, 18(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/13-102

Esch, T. (2014). Die neuronale Basis von Meditation und Achtsamkeit. Sucht, 60(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1024/0939-5911.a000288

Esch, T. (2020). Der Nutzen von Selbstheilungspotenzialen in der professionellen Gesundheitsfürsorge am Beispiel der Mind-Body-Medizin [Self-healing in health-care: Using the example of mind-body medicine]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz, 63(5), 577–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-020-03133-8

Esch, T., & Brinkhaus, B. (2020). Neue Definitionen der Integrativen Medizin: Alter Wein in neuen Schläuchen? Complementary Medicine Research, 27(2), 67–69. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506224

Esch, T, & Brinkhaus, B. (Eds.). (2021). Integrative Medizin und Gesundheit (1st ed.). MWV Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft.

*Fang, R., & Li, X. (2015). A regular yoga intervention for staff nurse sleep quality and work stress: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(23–24), 3374–3379. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12983

Feicht, T., Wittmann, M., Jose, G., Mock, A., Hirschhausen, E., & Esch, T. (2013). Evaluation of a seven-week web-based happiness training to improve psychological well-being, reduce stress, and enhance mindfulness and flourishing: A randomized controlled occupational health study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013, 676953. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/676953

*Flaxman, P. E., & Bond, F. W. (2010). Worksite stress management training: Moderated effects and clinical significance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(4), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020522

*Flook, L., Goldberg, S. B., Pinger, L., Bonus, K., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Mindfulness for teachers: A pilot study to assess effects on stress, burnout and teaching efficacy. Mind, Brain and Education, 7(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12026

Fox, K. C. R., Nijeboer, S., Dixon, M. L., Floman, J. L., Ellamil, M., Rumak, S. P., Sedlmeier, P., & Christoff, K. (2014). Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 43, 48–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016

*Franco, C., Mañas, I., Cangas, A. J., Moreno, E., & Gallego, J. (2010). Reducing teachers’ psychological distress through a mindfulness training program. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 655–666. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1138741600002328

Gaiswinkler, L., & Unterrainer, H. F. (2016). The relationship between yoga involvement, mindfulness and psychological well-being. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 26, 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2016.03.011

Gotink, R. A., Meijboom, R., Vernooij, M. W., Smits, M., & Hunink, M. G. M. (2016). 8-week Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction induces brain changes similar to traditional long-term meditation practice – A systematic review. Brain and Cognition, 108, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2016.07.001

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M. S., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., Berger, Z., Sleicher, D., Maron, D. D., Shihab, H. M., Ranasinghe, P. D., Linn, S., Saha, S., Bass, E. B., & Haythornthwaite, J. A. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018

*Grégoire, S., & Lachance, L. (2015). Evaluation of a brief mindfulness-based intervention to reduce psychological distress in the workplace. Mindfulness, 6(4), 836–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0328-9

*Grégoire, S., Lachance, L., & Taylor, G. (2015). Mindfulness, mental health and emotion regulation among workers. International Journal of Wellbeing, 5(4), 96–119. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v5i4.444

Griffith, G. M., Hastings, R. P., Williams, J., Jones, R. S. P., Roberts, J., Crane, R. S., Snowden, H., Bryning, L., Hoare, Z., & Edwards, R. T. (2019). Mixed experiences of a mindfulness-informed intervention: Voices from people with intellectual disabilities, their supporters, and therapists. Mindfulness, 10(9), 1828–1841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01148-0

Grossman, P. (2015). Mindfulness: Awareness informed by an embodied ethic. Mindfulness, 6(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0372-5

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006

*Hartfiel, N., Havenhand, J., Khalsa, S. B., Clarke, G., & Krayer, A. (2011). The effectiveness of yoga for the improvement of well-being and resilience to stress in the workplace. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 37(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.2916