Abstract

Objectives

The prevalence of overweight and obesity is high in adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), and the availability of and engagement in self-determined health and wellness programs is limited. The objective of the present study was to assess the effectiveness of the Mindfulness-Based Health Wellness (MBHW) program of using telehealth to enable families to teach a field-tested lifestyle change program to their adolescents with IDD. The program encouraged the adolescents to self-determine the parameters of the program that they could use to self-manage their weight through a lifestyle change process.

Method

Eighty adolescents were randomized into experimental (n = 42) and control (n = 38) groups. The experimental group engaged in the MBHW program as taught by their families, and the control group engaged in treatment as usual (TAU) in a randomized controlled trial. Adolescents in the experimental group self-determined the parameters of each of the five components of the MBHW program and engaged in self-paced weight reduction using a changing-criterion design.

Results

All 42 adolescents in the experimental group reached their target weights and, on average, reduced their weight by 38 lbs. The 38 adolescents in the control group reduced their weight by an average of 3.47 lbs. by the end of the study. There was a large statistically significant effect of the MBHW program on reduction of both weight and body mass index (BMI) for adolescents in the experimental group. Family members and adolescents rated the MBHW program as having high social validity, and the intervention was delivered with a high degree of fidelity.

Conclusions

Families can support adolescents with IDD to use the MBHW program to effectively self-manage their weight through a lifestyle change program. Future research should use an active control group, assess maintenance of weight loss across settings and time, use relative fat mass (RFM) for estimating body fat percentage, and evaluate the impact of consuming highly processed foods on weight loss interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

People with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) typically evidence compromised health status due to numerous health inequities when compared to their neurotypical peers (Havercamp & Bonardi, 2022; Johnston et al., 2022). For example, people with IDD generally have a much higher level of inactivity and sedentary behavior than those in the general population, which is linked to higher rates of cardio-metabolic risks, obesity, and multi-morbidity (Gawlik et al., 2018; Same et al., 2016; Tyrer et al., 2019). In turn, obesity has been reported to underlie many chronic health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, osteoporosis, and depression (Phillips et al., 2014; Ranjan et al., 2018; Sari et al., 2016), as well as some cancers (Patterson et al., 2013). Unfortunately, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in people with IDD can be as high as 69% (Ryan et al., 2021). The level of obesity also varies with the level of intellectual impairment in people with IDD (86%, 72%, and 51% in mild, moderate, and severe/profound, respectively) and type of residence (79% of those who lived independently or with family, 74% in group homes, and 60% in residential care; Ryan et al., 2021).

The gravity of health concerns due to obesity has resulted in increased attention being paid to developing and evaluating interventions for people with IDD. Early studies included both single- and multiple-component weight reduction programs (Spanos et al., 2013). For example, (a) Mendonca et al. (2011) and Wu et al. (2010) reported programs that used physical activity alone, (b) McCarran and Andrasik (1990) and Sailer et al. (2006) used behavioral self-control programs, (c) Fisher (1986) and Fox et al. (1984) used physical activity combined with behavioral self-control, (d) Bertoli et al. (2008) used diet alone, (e) Chapman et al. (2005) used physical activity and diet, and (f) Melville et al. (2011) and Saunders et al. (2011) used physical activity, diet, and behavior change strategies. Each of these studies reported successful interventions, with statistically significant weight loss in the participants. However, the absolute changes in body weight in these studies failed to meet the National Institutes of Health (National Institutes of Health [NIH], 2000) guidelines for the clinically significant mean weight loss criterion of 5 to 10% of initial body weight.

More recent studies have produced clinically significant reductions in weight in some or all participants that met the NIH criterion of 5 to 10% reduction of preintervention body weight. For example, Nabors et al. (2021) reported a pilot study that evaluated a healthy eating and exercise program for young adults with IDD. Of the 17 young adults who participated in the program, five met the NIH criterion with 5 to 10% reductions in their initial body weight. While other participants reported minimal changes, some reported increased body weight by the end of the program. However, all benefitted from the program in terms of improved knowledge of health behaviors. In another pilot study, Matheson et al. (2019) evaluated the effects of a parent-delivered weight-loss treatment for autistic children. While pre-and post-intervention weights of the autistic children were not reported, six lost 9.5 lbs. by the end of the treatment period, with two reaching healthy weight range. Whether the reduction in weight met NIH guidelines could not be established from the reported data.

Ptomey et al. (2018) reported a randomized controlled trial of two dietary approaches to weight management in adults with IDD who had mild to moderate intellectual impairments. The experimental diet was the enhanced Stop Light Diet (eSLD), which led to 6.4% and 8.7% weight loss at 6 months and 12 months, respectively, in a similar population in a single-arm study (Saunders et al., 2011). In the Ptomey et al. (2018) two-arm study, the eSLD diet was compared to a conventional diet (CD; Jensen et al., 2014). The participants were also encouraged to increase their physical activity, self-monitor their diet, and attend monthly counseling/educational sessions. At 6 months, the participants in the eSLD arm evidenced 7% weight loss compared to 3.8% in the CD arm. But, at 18 months, there was negligible difference between the two conditions, with those in the eSLD arm reporting 6.7% vs. 6.4% in the CD arm. Both interventions met the NIH criterion for clinically meaningful weight loss at 18 months of intervention.

Shlesinger et al. (2018) evaluated the effectiveness of a comprehensive health-wellness intervention on weight and body mass index (BMI) in five residential school students with neurodevelopmental disorders. The participants ranged in age from 11 to 19 years, were diagnosed with autism and co-occurring disorders, and were obese in terms of their BMI. Following a 1-month baseline phase, they participated in the intervention that included (a) diet-nutrition, (b) exercise-physical activity, (c) health informatics monitoring, and (d) care provider training. The length of the intervention ranged from 15 to 25 weeks. Results showed substantial decreases in both weight and BMI during the intervention. The weight loss across the five participants was 19%, 16%, 7%, 8%, and 19%, respectively. These figures indicate that all five participants met the NIH criterion for clinically meaningful weight loss. Duhanyan et al. (2020) systematically replicated the procedures used in this study with an additional four participants who were aged 16 to 19 years and diagnosed with autism. Following intervention, the four evidenced 9%, 11%, 23%, and 15% weight loss by the end of the intervention, again meeting the NIH criterion for clinically meaningful weight loss. In terms of social validity, parents of the adolescents positively rated the intervention with regard to procedures and outcomes.

The Mindfulness-Based Health Wellness (MBHW) program, a multicomponent intervention that consists of mindfulness-based practices, physical exercise, behavioral strategies, and nutrition knowledge, was developed to enable people to make lifestyle changes that lead to self-management of weight and enhanced physical wellness. In the initial study, Singh et al. (2008a) used an early version of the MBHW program with a 30-year-old neurotypical man who was morbidly obese and wanted a lifestyle change. The man successfully reduced his weight from 315 to 171 lbs. and maintained the reduced weight during the 5-year follow-up period. His lifestyle change involved increased physical activity, greater food awareness, eating healthy foods, and not eating rapidly, which resulted in substantially reducing serious medical risk factors, and eliminated physical discomfort and mobility problems due to his excessive weight.

The MBHW program was used as an intervention with an adolescent with Prader-Willi syndrome, which is commonly linked with relentless food seeking, insatiable appetite, and obesity (Singh et al., 2008b). After several failed attempts at managing his obesity through a wide range of weight management programs, his family requested that he be given the opportunity to use the MBHW program. At baseline, his weight was 256 lbs. He then participated in the MBHW program using a changing-criterion design (Barlow et al., 2009), which enabled him to make choices regarding the number and length of each step in the changing criterion for weight reduction, with a goal of achieving body weight of 200 lbs. He reached his pre-determined weight and then maintained his weight below 200 lbs. during the 3-year follow-up period. In a follow-up study, three individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome used an enhanced version of the MBHW program, reached their desired body weight, and maintained the gains during the 3-year maintenance period (Singh et al., 2011). The first adolescent’s weight was 345 lbs. at baseline and 146 lbs. at termination of the program, with an average weight of 140 lbs. during the 3-year follow-up period. The second adolescent’s weight was 153 lbs. at baseline and 111 lbs. at termination of the program, with an average weight of 106 lbs. during the 3-year follow-up period. The third adolescent’s weight was 150 lbs. at baseline and 106 lbs. at termination of the program, with an average weight of 96 lbs. during the 3-year follow-up period. The adolescents in both of these studies more than met the NIH criterion for clinically meaningful weight loss. The addition of opportunities for self-determined actions and the use of self-determination skills (e.g., choice making, decision-making, goal setting, self-management) were an enhancement to this intervention and align with theory and research suggesting that creating opportunities for self-determination can enhance motivation and goal attainment across life domains (Shogren & Raley, 2022).

In a larger study, Myers et al. (2018) assessed the effectiveness of a telehealth parent-delivered MBHW program with overweight or obese adolescents and young adults with IDD on their body weight within a changing-criterion design. The five-component MBHW program included physical exercise, healthy eating and nutrition, mindful eating, mindful response to thoughts of hunger, and a mindfulness practice to control the urge to eat. The 30 participants who successfully completed the program had an average weight of 164 lbs. at baseline, lost an average of 37 lbs. (23%) by the end of intervention, and maintained their target weight for four consecutive years at a mean weight of 127.37 lbs. In terms of social validity, the participants’ self-ratings showed great satisfaction with the program in meeting their desired weight goals, and they unanimously indicated that they would recommend the program to their peers. The data suggested the MBHW program exceeded the NIH criterion for clinically meaningful weight loss and that further evaluation using a randomized controlled trial (RCT) was warranted.

The aim of the present study was to directly replicate and extend the findings of Myers et al. (2018) by evaluating the effectiveness of a telehealth family-delivered MBHW program for adolescents with IDD on their body weight when compared to treatment as usual (TAU) in a RCT. We hypothesized that families will successfully learn the MBHW program via telehealth training and teach their adolescents with IDD to use the program with fidelity, resulting in greater clinically and statistically significant weight loss when compared to a TAU condition.

Method

Participants

We conducted a power analysis to estimate appropriate sample size for multiple linear regression (MLR) with two predictors. To detect an effect size f2 of 0.15 with probability of 80% and p < 0.05, the estimated required sample size was 68 cases. In anticipation of attrition, we initially recruited a larger sample of participants. The eligibility criteria for inclusion in the study required the participant to (a) be an adolescent with IDD; (b) be overweight or obese (i.e., BMI of 25 or above) as certified by their family physician or nurse; (c) have medical clearance to participate in the MBHW program; (d) express an interest and motivation to engage in a healthy lifestyle; (e) be committed to adhering to the program requirements over several years; (f) agree to a regular six-monthly medical checkup by their family physician and being weighed by the nurse; (g) have access to a personal smartphone; and (h) have two caregivers (i.e., both parents or a parent and one other adult family member) who (i) were committed to assisting the participants to engage in the program protocol; (ii) were willing to be trained in the experimental procedures; (iii) agreed to participate in the program across several years; (iv) agreed to communicate with the researchers on a regular basis; and (v) had access to Google Hangouts and WhatsApp for telehealth training and communication.

We recruited possible participants via a number of sources, including relevant listservs in developmental disabilities, word of mouth, announcements in family physician offices, and convenience sampling. This resulted in an initial sample of 112 possible participants who resided throughout the USA. Of the 86 that met eligibility criteria, 43 were assigned (using simple randomization) to the MBHW experimental group and 43 to the TAU group. Prior to the initiation of the study, 1 participant dropped out of the MBHW group and 5 from the TAU group due to personal and family reasons. This left a total of 42 adolescents in the MBHW group and 38 in the TAU group. All adolescents had mild impairments in intellectual functioning, and their ages ranged from 13 to 20 years, with an average age of 17 years (SD = 1.41). Twelve received prescribed psychotropic medications for psychiatric disorders. None of the adolescents had Prader-Willi syndrome or other appetite-related disorders that could have been associated with overweight and obesity. Weight at entry into the study was assessed by a nurse at each adolescent’s primary care setting, and medical clearance was obtained from the family physician for participation in the study. The adolescents had a history of engaging in weight reduction initiatives, including behavior management plans, restricted diets, physical exercise, over-the-counter drugs, and designer weight reduction meal plans, but none of these produced significant or sustained weight reduction. Table 1 presents the participants’ key demographic characteristics. There were no significant age and sex differences between the MBHW and TAU groups (p > 0.50), but there were significantly more males in both groups (n = 58) compared to females (n = 22), χ2(1) = 16.20, p < 0.001.

As for family participants, 80 mothers, 52 fathers, and 28 other family members of the adolescents participated in the study. All of them volunteered to learn the MBHW program and to implement it with the adolescents. The mean age of the group of family members was 46.5 years. They self-reported their socioeconomic status as middle class, were educated at the community college or university level, and had regular full-time or part-time employment.

Procedure

The study was a RCT with adolescents with IDD using the MBHW program vs. TAU. Given the MBHW group used a changing-criterion design (Barlow et al., 2009), following randomization, the TAU group participants were yoked 1:1 to the RCT participants so that the data collection period was the same for each yoked pair of participants. Overall, the procedure was a direct replication of the Myers et al. (2018) study for the MBHW group but updated for healthy eating and nutrition information. The participants’ family members were responsible for teaching and implementing the MBHW program with their adolescents. In a two-stage intervention process, telehealth training on the MBHW program was provided to the family members followed by in vivo training of the adolescents by their family members.

Telehealth Training of Family Members

Training

The telehealth aspect of the procedure involved providing instructions to the family members via Google Hangouts (a web-based communication platform now upgraded to Google Chat) during the 10-week baseline phase. As in the Myers et al. (2018) study, the training involved “(1) explaining the study protocol to each family members; (2) explaining the 5-component intervention; (3) rehearsing or discussing each component of the intervention, with increasing depth as training progressed, until the family members achieved knowledge and competency on the training steps; (4) engaging in the mindfulness interventions so that the family members would be able to respond to any experiential questions posed by their adolescent; (5) role playing the training with each other in preparation for teaching their adolescent; (6) learning data collection and reliability procedures; and (7) developing a procedure and schedule for transmitting the data via WhatsApp, an encrypted instant messaging system for smartphones” (p. 243).

During the training, support for the family members was provided in real time matched to their training needs when they most needed or wanted assistance. Such real-time support has the potential for skillfully assisting family members when they may not know how to handle next steps in the training or may be likely to err in the training sequence or content. We used a variation of the just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs; Nahum-Shani et al., 2017) methodology which enabled us to dynamically respond to the training needs of the family members through provision of the right amount and type of support at the right time via telehealth technology. The family members needed an average of 10 to 12 h of instructional time from the expert MBHW program trainer and an average of 2 h of JITAI assistance.

Competency of Family Members

The family members’ competency in terms of skills displayed when teaching and implementing the MBHW program was rated via live Google Hangouts on a 20-item MBHW Skills Training Monitoring Form. An expert MBHW program trainer observed and rated two training sessions per participant during the first week of training.

Trainer

An expert MBHW trainer who had a life-long personal practice of meditation and extensive experience in training families led the instructions for the family members in all aspects of the study protocol. Training was provided to members of the family who volunteered to be included in the study.

In Vivo Training of the Adolescents

Experimental Design

To assess the effectiveness of the MBHW program in a controlled manner within the RCT, we used a changing-criterion design (Barlow et al., 2009), with a 10-week baseline phase and an intervention phase with self-directed criterion changes. A 10-week baseline phase was instituted to assess the weekly weight of the participants in the absence of any programmed intervention. The participants were encouraged to continue with their typical eating and health management routines. In addition, together with their family members, the adolescents weighed and recorded their weights on the same day and at about the same time each week.

Experimental Intervention: The Mindfulness-Based Health Wellness (MBHW) Program

The family members instructed their adolescents in the components and requirements of the MBHW program, one component at a time. They used standard behavioral instructions that included successive approximations and errorless learning strategies, demonstrations, modeling, and positive reinforcement for learning. The five components of the MBHW program were adapted and updated from those used in previous studies (Myers et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2008a, b, 2011). A brief description of the five components of the MBHW program is presented in Table 2, an updated summary of nutritional guidance on healthy eating (i.e., second component) is presented in Table 3, and the training steps for the Soles of the Feet (SoF) practice for hunger (i.e., fifth component) are presented in Table 4.

The intervention included opportunities for the adolescents to make choices in each component of the MBHW program. For example, with the weight reduction component, the adolescents were required to self-determine the number of pounds of weight they planned to reduce at each criterion change. The changing-criterion design enabled each participant to use stepwise benchmarks for self-paced reduction of weight, thus enabling successive approximations to their eventual desired weight. To meet the requirements of the experimental design, the adolescents needed to reduce their weight to just below the pre-determined number of pounds during three consecutive weeks before they could step down to the next level. All adolescents set the criterion change at 5 lbs. for ease of remembering the amount of weight they needed to reduce at each step. That is, they reduced the weight requirement by 5 lbs. when three consecutive weekly weight measurements were at or just below the existing weight criterion. The length of each criterion change was not preset, and the participants were free to work on weight reduction at their own pace, moving as quickly or slowly as they could manage. In part, this was determined by how well their body adjusted to the changing nutritional intake during the intervention, thus avoiding premature weight plateaus before reaching their target weights (Franz et al., 2007). At their weekly weighing, the family members and adolescents discussed current weight, the current weight criterion goal, and when a new weight criterion could come into effect.

Control Intervention: Treatment as Usual (TAU)

Each family controlled their adolescent’s weight using methods of their choosing and could make changes during the study. The range of methods used included physical exercise, restricted eating, commercial diet programs, dietitian-developed meal plans, behavioral weight management programs, family-initiated meal plans, restricted fast foods, and no formal or informal interventions. The family members reported the procedures used, as well as any changes made during the study.

Measures

We used the same definitions, procedures, and measures for collecting outcome data as specified in the Myers et al. (2018, pp. 246–247) study, namely (1) each adolescent’s weight as measured by the adolescents (weekly during baseline and intervention phases); (2) reliability checks on the adolescent’s weight as measured by one of the family members; (3) six-monthly weight data as measured by the adolescent’s family physician nurse; (4) criterion changes; (5) BMI (i.e., weight divided by height squared) recorded in the last week of baseline and the last week of intervention; and (6) social validity ratings by the participants and family members at the end of the intervention phase. These outcome measures were recorded for the experimental and control groups, except for criterion changes and social validity ratings which were applicable only for the experimental group participants. In addition, we collected data on fidelity in terms of teaching and implementation of various aspects of the MBHW program, including (a) observation by the expert MBHW trainer of family members training of the SoF practice to their adolescents and rated on the 40-item Meditation on the Soles of the Feet (SoF) Trainer Monitoring Form, and (b) the following four aspects of the MBHW program: (i) adherence (i.e., extent to which the core training components of each program were taught); (ii) dosage (i.e., the number of training sessions delivered); (iii) quality (i.e., extent to which the trainer delivered the program components and contents as intended); and (iv) responsiveness (i.e., extent to which the trainer was responsive and skillfully engaged with the participants) (Dane & Schneider, 1998).

Data Analyses

The family members submitted all data weekly throughout the baseline and intervention phases using WhatsApp. Research staff checked the data weekly for completeness and followed up with the family members if the data were incomplete or delayed. This procedure resulted in no missing data.

Given the amount of weight loss was highly individualized, MLR was conducted with the participants’ weight and BMI post-intervention as outcome variables and the MBHW (vs TAU) as the main predictor while controlling for the baseline weight and BMI. Weight and BMI data were distributed close to normal with no significant outliers, and skewness and kurtosis values were within conservative criteria of ± 1 meeting assumptions of the MLR.

Results

Process Outcomes

Competency of Family Members in Using the MBHW Program .

The competency ratings of the family members across 84 training sessions (i.e., two training sessions per participant) ranged from 86 to 97% (mean = 93%).

Walking

Adherence to the self-determined walking schedule and goal in terms of number of steps walked ranged from 76 to 100% (mean = 88%) across all participants during the experimental intervention.

Weight

Reliability of weight assessments by the family members and adolescents was defined as both reporting the participant’s weight within ± 1 lb. Agreement reliability was computed at 100% for the duration of the study. A second independent reliability check, performed twice a year by the family physician’s nurse during six-monthly physician wellness examinations, also showed an agreement reliability of 100%.

Criterion Changes

The adolescents’ self-determined average number of criterion changes needed to reach target weight goals ranged from 3.60 to 11.20, with a mean of 7.60 changes.

Time to Target Weight

Given that each adolescent self-determined the time taken to reach each stepwise weight criterion meant that the time to reach the final target weight criterion varied across participants. On average, the length of time to final target weight was 83 weeks (SD = 13.50), with substantial variability across the adolescents.

Fidelity

The overall fidelity ratings of 84 family members’ training sessions of SoF with their adolescents ranged from 82 to 98% (mean = 94%). In terms of dimensions of family members’ implementation of the MBHW program, the overall fidelity ratings were (i) 100% for teaching the core training components of the program (i.e., adherence); (ii) 100% for the number of training sessions delivered (i.e., dosage); (iii) a mean of 85% (range = 82 to 97%) for the extent to which the trainer delivered the program components and contents as intended (i.e., quality); and (iv) a mean of 92% (range = 87 to 100%) for the extent to which the trainer was responsive and skillfully engaged with the participants (i.e., responsiveness).

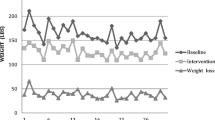

Program Outcomes

All 42 participants in the experimental group reached their target weights. On average, the participants in the experimental group had a baseline (pre-intervention) weight of 178.83 lbs., a post-intervention weight of 140.83 lbs., and a weight loss of 38 lbs. In comparison, the participants in the control group had an average baseline (pre-intervention) weight of 173.39 lbs., a post-intervention weight of 169.92 lbs., and a weight loss of 3.47 lbs. (Fig. 1). On average, the participants in the experimental group had a baseline (pre-intervention) BMI of 29.50, a post-intervention BMI of 23.16, and BMI decrease of 6.34. In comparison, the participants in the control group had an average baseline (pre-intervention) BMI of 29.76, a post-intervention BMI of 29.13, and a BMI decrease of 0.63 (Fig. 2).

Mean weights for the MBHW and TAU groups at the baseline and after the MBHW intervention. Mean difference is statistically significant at baseline (p < 0.05) and at post-intervention (p < 0.01). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Note: MBHW = Mindfulness-Based Health Wellness program; TAU = treatment as usual

Mean body mass index (BMI) for the MBHW and TAU groups at the baseline and after the MBHW intervention. Only post-intervention mean difference is statistically significant (p < 0.01). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Note: MBHW = Mindfulness-Based Health Wellness program; TAU = treatment as usual

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations (SD), and standard error of the mean for weight and BMI at the baseline and post-intervention by experimental and control groups are presented in Table 5. The main results of the MLR analyses are included in Table 6 and show that after controlling for the baseline weight and BMI, a large statistically significant effect of the MBHW on reduction of both weight and BMI was evident by f2 > 3.00. This large effect size of the MBHW is reflected by standardized β close to 0.90, which predicts a weight and BMI reduction for almost one standard deviation by virtue of the MBHW based on the sample distribution. There was a significant effect of the baseline weight and BMI supporting usefulness to control for it contributing to higher precision of the main results.

Social Validity

The 42 adolescents from the experimental group rated five social validity statements with reference to the MBHW program they had engaged in. Ratings were on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). When asked if they were keen to be enrolled in the health wellness program, 5 adolescents stated they were neutral, 22 were somewhat keen, and 15 were strongly keen (Table 7). This range of responses suggests that some family members may have subtly influenced their adolescents into participating in the program. All adolescents agreed that it was worth participating in the program, and while it was effortful and time consuming, it enabled them to meet their lifestyle change goals. In addition, all adolescents stated they would recommend the MBHW program to their peers. Finally, all family members highly rated the social validity of the program in terms of meeting their adolescent’s lifestyle change goals.

Discussion

This study can be contextualized within a developmental framework for evaluating the effectiveness of an emerging intervention for self-managing weight within a lifestyle change process (Onken et al., 2014; Rounsaville et al., 2001). The MBHW program was developed to assist people who had difficulty in self-managing their weight for whatever reason. The initial studies focused on developing and testing whether the intervention was internally valid and could be replicated across individuals with or without a biological basis for their weight gains (Singh et al., 2008a, b, 2011). Once initial effectiveness of the intervention was minimally established, Myers et al. (2018) undertook a feasibility study that assessed whether the MBHW program could be used in the community by parents to teach their adolescents with IDD to self-manage their weight. The present study extended this research trajectory by testing the external validity of the MBHW program in a randomized controlled trial with similar participants and directly replicating the Myers et al. (2018) intervention protocol.

The key finding of the present study was that families can support adolescents with IDD to use the MBHW program effectively to self-manage their overweight and obesity. The effect size for weight reduction was large and exceeded the NIH (2000) guidelines for clinically significant mean weight loss criterion of 5 to 10% of initial body weight. In addition, there was a large effect size for reduction in BMI across participants in the experimental group. Ratings by the adolescents and their families indicated that the MBHW program had a high degree of social validity. Furthermore, this study showed that family members could be taught the program protocol via telehealth, followed by the family members undertaking in vivo training of their adolescents with high degree of training fidelity, and tracking and making the data available to the researchers on an App in real time. One of the key next steps in the development of this intervention should involve effectiveness research that examines its utility in community settings, with community therapists/providers. Such research could also include an examination of the moderators and the mechanisms of action of the program components (Kazdin, 2007, 2008; Weisz et al., 2014). For example, it would be of some importance to assess how much of the outcome variance can be accounted for by embedding self-determination throughout the intervention components.

Pilot and feasibility studies with small samples of people with IDD have reported statistically and/or clinically significant reductions in weight loss in some or all participants (e.g.,Duhanyan et al., 2020; Matheson et al., 2019; Nabors et al., 2021; Shlesinger et al., 2018). In the only two-arm RCT study that compared dietary interventions, Ptomey et al. (2018) reported differential weight loss due to the two interventions at 6 months, but the difference was not maintained at 18 months. However, both interventions met the NIH criterion for clinically meaningful weight loss in the participants. Research on lifestyle change for enhancing health and wellness in people with IDD is very limited, with a meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials showing significant change effects only for waist circumference (Willems et al., 2018). The present study adds to the literature on lifestyle change, showing large effect sizes for weight loss and reduction in BMI to within the normal range in the experimental group.

There has been a call for mindfulness-based programs to embed opportunities for self-determination throughout the intervention delivery to enhance the participants’ intrinsic motivation to engage in mindfulness-based programs (Shogren & Singh, 2022). Indeed, having self-determination seamlessly infused within a program may enhance the participants’ sense of self-management of the process of the intervention. A strength of the present study was that opportunities for self-determination were embedded throughout the intervention, and engaging in self-determined actions (e.g., choice making, goal setting, self-directing, and managing activities) was a requisite component for being fully engaged in the program. For example, the participants had (a) to decide on the form of their physical exercise, how many steps to take each day, and what distal reinforcers to use as positive consequences for meeting their goals; (b) an abundance of daily choices with regard to healthy eating; (c) to determine how to eat each meal mindfully; (d) to choose a visualization to personify their feelings of hunger between meals; and (e) to decide when to engage in the SoF practice to rapidly gain control over their urge to eat between meals and to stop eating at the first sign of feeling full. The strongest component, however, was embedded in the changing-criterion design which required the participants to choose and set the goals for the pace at which they reduced their weight in a stepwise fashion. Taken together, this profusion of opportunities for self-determined actions likely contributed to enhanced intrinsic motivation as well as enhanced goal-directed actions in the MBHW program. This enhanced motivation most likely supported persistence with the MBHW program when motivation waned, but this remains an empirical question for future research.

Another consideration is that the MBHW program was contextualized within a family systems perspective. While there are many ways of reducing weight in the short term, a lifestyle change program that can be maintained over time by people with intellectual impairments requires social support from family members. The MBHW program is a robust lifestyle change intervention that may be difficult to initiate, implement, and maintain by almost any individual without family or social support. Given the length of the intervention, intrinsic motivation may wane when weight reduction slows or reverses direction, when the individual’s body physiology reaches a stuck point as it invariably does in weight reduction programs, or when psychological factors in obesity (e.g., low self-worth, poor body image, self-criticism, occasional emotional eating) overwhelm the individual. In such situations, family members who not only assist with the program but also engage in various aspects of the lifestyle change process itself provide much needed strength and support for the individual with intellectual impairment to persist with their lifestyle goals.

An additional strength of the present study is that it used mainstream wireless technology that is readily available to everyone, including people with IDD. Given the connectivity, size, portability, and ease of use, people with IDD use smartphones at about the same rates as the general population in western countries (Morris et al., 2017), and increasingly so in eastern countries, such as in India (Arun & Jain, 2022) and South Korea (Kim & Lee, 2021). In addition, smartphones and tablets are being used for programming daily activities for people with IDD, such as for independently accessing leisure activities and making video calls to others in the community (Lancioni et al., 2017, 2020). Using mainstream wireless technology for telehealth programs, such as the MBHW program used in the present study, provides a seamless way of engaging families in health wellness programs.

Limitations and Future Research

This study is not without limitations. The key limitation is the use of TAU instead of an active control condition comparable with the MBHW program. While much can be said for assessing the effects of a new intervention against what is currently available to and used by families and their children, only an active control condition can answer the crucial question about effectiveness. In our study, a TAU or no-treatment control group served as a neutral comparison for the experimental group receiving the MBHW program. One problem with the use of a TAU control group is the likelihood of placebo effects that may enhance the effectiveness of the experimental group due to expectation of improvement. Mindfulness-based interventions, like the MBHW program, have a high risk of expectation bias, and the participants may show purported intervention effects which could have resulted from non-specific factors such as quality of therapeutic alliance and relationship, empathy, being non-judgmental, time spent with a reflective person, and so on. The likelihood of such effects is much lower when parents or families are the therapists, and the target variable (weight) is produced by physiological/biological and behavioral changes which are not easily susceptible to non-specific factors. However, to have a methodologically rigorous efficacy or effectiveness study, an active control condition is needed that mimics the mechanics of the experimental intervention but without the specific mechanisms that produce its effects. We also highlighted how the inclusion of opportunities for self-determining engagement across all phases of the intervention is a strength of the MBHW program; however, ongoing research is also needed to examine direct impacts on self-determination, motivation, and optimal ways to promote self-determination in health and wellness lifestyle interventions.

Another limitation is the lack of maintenance data across settings (e.g., when the adolescents move from home into independent living arrangements) or time (i.e., long-term follow-up). There are innumerable diets and fads that can readily reduce a person’s weight in the short term, but the key is maintenance of the weight change over time. Fortunately, earlier studies of the MBHW program provide suggestive evidence of what might be expected in terms of long-term maintenance of such a lifestyle change program. These studies show that the effects are maintained for at least 3 years (Singh et al., 2008b), 4 years (Myers et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2011), or 5 years (Singh et al., 2008b) post-intervention without regaining lost weight.

Previous studies on weight reduction in people with IDD defined overweight and obesity in terms of BMI reflecting an index of weight for height. Following the World Health Organization (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight), overweight has been defined as BMI equal to or greater than 25 and obesity as equal to or greater than 30. Aligned with previous studies, we also used this reporting standard for weight in our intervention studies. However, recent studies have reported that BMI and high body fat percentage (i.e., adipose tissue mass relative to total body weight) are independently associated with increased mortality (Padwal et al., 2016). The issue of BMI having limited accuracy in estimating body fat percentage may result in misclassification of body fat–defined obesity (Romero-Corral et al., 2008). A recent study has suggested that relative fat mass (RFM) may be a better predictor of whole-body fat percentage (Woolcott & Bergman, 2018) and that RFM can be used clinically to improve body fat–defined obesity classification. This should be a consideration in future clinical intervention studies.

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/default.aspx), over a third of children and adolescents in the USA consume fast food daily. Fast foods are highly processed foods (HPFs) that include refined carbohydrates and/or added fats and are high in sodium. Regular consumption of HPFs result in negative consequences, including 12% of children exhibiting addictive-like eating phenotype, otherwise known as food addiction (Gearhardt & Schulte, 2021). In addition to being associated with such characteristics as impulsivity, reward dysfunction, and emotional dysregulation, it may lead to lower quality of life and poor response to weight-loss interventions (Gearhardt & DiFeliceantonio, 2022). Given these findings and their direct applicability to people with IDD we added a cautionary note on consuming HPFs in the nutritional guidelines included in the MBHW program. We are uncertain of the impact of regularly consuming HPFs on weight reduction efforts, but suggest that future research explore it in the interest of providing better community public health and wellness education, including to those on the neurodevelopmental continuum.

Data Availability

The data are available in Supplementary Materials.

References

Arun, P., & Jain, S. (2022). Use of smart phone among students with intellectual and developmental disability. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, 9, 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-022-00279-3

Barlow, D. H., Nock, M., & Hersen, M. (2009). Single-case experimental designs (3rd ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Bertoli, S., Spadafranca, A., Merati, G., Testolin, G., Veicsteinas, A., & Battezzati, A. (2008). Nutritional counseling in disabled people: Effects on dietary patterns, body composition and cardiovascular risk factors. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 44(2), 149–158.

Chapman, M. J., Craven, M. J., & Chadwick, D. D. (2005). Fighting fit? An evaluation of health practitioner input to improve healthy living and reduce obesity for adults with learning disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 9(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629505053926

Dane, A. V., & Schneider, B. H. (1998). Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control. Clinical Psychology Review, 18(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00043-3

Duhanyan, K., Shlesinger, A., Bird, F., Harper, J. M., & Luiselli, J. K. (2020). Reducing weight and body mass index (BMI) of adolescent students with autism spectrum disorder: Replication and social validation of a residential health and wellness intervention. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 4(2), 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-020-00153-y

Fisher, E. (1986). Behavioral weight reduction program for mentally retarded adult females. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 62, 359–362. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1986.62.2.359

Fox, R. A., Haniotes, H., & Rotatori, A. (1984). A streamlined weight loss program for moderately retarded adults in a sheltered workshop setting. Applied Research in Mental Retardation, 5(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0270-3092(84)80020-X

Franz, M. J., VanWormer, J. J., Crain, A. L., Boucher, J. L., Histon, T., Caplan, W., Bowman, J. D., & Pronk, N. P. (2007). Weight-loss outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(10), 1755–1767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017

Gawlik, K., Zwierzchowska, A., & Celebańska, D. (2018). Impact of physical activity on obesity and lipid profile of adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(2), 308–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12406

Gearhardt, A. N., & DiFeliceantonio, A. G. (2022). Highly processed foods can be considered addictive substances based on established scientific criteria. Addiction, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16065

Gearhardt, A. N., & Schulte, E. M. (2021). Is food addictive? A review of the science. Annual Review of Nutrition, 41, 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-110420-111710

Havercamp, S. M., & Bonardi, A. (2022). Special issue introduction: Addressing healthcare inequities in intellectual disability and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 60(6), 449–452. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-60.6.449

Jensen, M. D., Ryan, D. H., Apovian, C. M., Ard, J. D., Comuzzie, A. G., Donato, K. A., Hu, F. B., Hubbard, V. S., Jakicic, J. M., Kushner, R. F., Loria, C. M., Millen, B. E., Nonas, C. A., Pi-Sunyer, F. X., Stevens, J., Stevens, V. J., Wadden, T. A., Wolfe, B. M., & Yanovski, S. Z. (2014). 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 63, 2985–3023. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee

Johnston, K. J., Chin, M. H., & Pollack, H. A. (2022). Health equity for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. JAMA, 328(16), 1587–1588. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.18500

Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432

Kazdin, A. E. (2008). Evidence-based treatment and practice: New opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. American Psychologist, 63(3), 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146

Kim, K. M., & Lee, C. E. (2021). Internet use among adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities in South Korea. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(3), 724–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12843

Lancioni, G. E., Singh, N. N., O’Reilly, M. F., Sigafoos, J., Alberti, G., Zimbaro, C., & Chiariello, V. (2017). Using smart phones to help people with intellectual and sensory disabilities perform daily activities. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 282. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00282

Lancioni, G. E., Singh, N. N., O’Reilly, M. F., Sigafoos, J., Alberti, G., Perilli, V., Chiariello, V., Grillo, G., & Turi, C. (2020). A tablet-based program to enable people with intellectual and other disabilities to access leisure activities and video calls. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 15(1), 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2018.1508515

Matheson, B. E., Drahota, A., & Boutelle, K. N. (2019). A pilot study investigating the feasibility and acceptability of a parent-only behavioral weight-loss treatment for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 49(11), 4488–4497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04178-8

McCarran, M. S., & Andrasik, F. (1990). Behavioral weight-loss for multiply handicapped adults: Assessing caretaker involvement and measures of behavior change. Addictive Behavior, 15(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(90)90003-G

Melville, C. A., Boyle, S., Miller, S., Macmillan, S., Penpraze, V., Pert, C., Spanos, D., Matthews, L., Robinson, N., Murray, H., & Hankey, C. R. (2011). An open study of the effectiveness of a multi-component weight-loss intervention for adults with intellectual disabilities and obesity. British Journal of Nutrition, 105, 1553–1562. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510005362

Mendonca, G. V., Pereira, F. D., & Fernhall, B. (2011). Effects of combined aerobic and resistance exercise training in adults with and without Down syndrome. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 92, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.09.015

Morris, J. T., Sweatman, W. M., & Jones, M. L. (2017). Smartphone use and activities by people with disabilities: User survey 2016. Journal on Technology and Persons with Disabilities, 5, 50–66.

Myers, R. E., Karazsia, B. T., Kim, E., Jackman, M. M., McPherson, C. L., & Singh, N. N. (2018). A telehealth parent-mediated mindfulness-based health wellness intervention for adolescents and young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 2(3), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-021-00192-z

Nabors, L., Overstreet, A., Carnahan, C., & Ayers, K. (2021). Evaluation of a pilot healthy eating and exercise program for young adults with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disabilities. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities, 5(4), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-021-00214-w

Nahum-Shani, I., Smith, S. N., Spring, B. J., Collins, L. M., Witkiewitz, K., Tewari, A., & Murphy, S. A. (2017). Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: Key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(6), 446–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9830-8

National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLB), and North American association for the Study of Obesity (NAASO). (2000). The practical guide: Identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Bethesda, MD: Author (NIH Publication # 00–4084).

Onken, L. S., Carroll, K. M., Shoham, V., Cuthbert, B. N., & Riddle, M. (2014). Reenvisioning clinical science: Unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(1), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613497932

Padwal, R., Leslie, W. D., Lix, L. M., & Majumdar, S. R. (2016). Relationship among body fat percentage, body mass index, and all-cause mortality: A cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164, 532–541. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-1181

Patterson, R. E., Rock, C. L., Kerr, J., Natarajan, L., Marshall, S. J., Pakiz, B., & Cadmus-Bertram, L. A. (2013). Metabolism and breast cancer risk: Frontiers in research and practice. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113, 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.08.015

Phillips, K. L., Schieve, L. A., Visser, S., Boulet, S., Sharma, A. J., Kogan, M. D., Boyle, C. A., & Yeargin-Allsopp, M. (2014). Prevalence and impact of unhealthy weight in a national sample of US adolescents with autism and other learning and behavioral disabilities. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(8), 1964–1975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1442-y

Ptomey, L. T., Saunders, R. R., Saunders, M., Washburn, R. A., Mayo, M. S., Sullivan, D. K., Gibson, C. A., Goetz, J. R., Honas, J. J., Willis, E. A., Danon, J. C., Krebill, R., & Donnelly, J. E. (2018). Weight management in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A randomized controlled trial of two dietary approaches. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31, 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12348

Ranjan, S., Nasser, J. A., & Fisher, K. (2018). Prevalence and potential factors associated with overweight and obesity status in adults with intellectual developmental disorders. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31. Suppl, 1, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12370

Romero-Corral, A., Somers, V. K., Sierra-Johnson, J., Thomas, R. J., Collazo-Clavell, M. L., Korinek, J., Allison, T. G., Batsis, J. A., Sert-Kuniyoshi, F. H., & Lopez-Jimenez, F. (2008). Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. International Journal of Obesity, 32(6), 959–966. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.11

Rounsaville, B. J., Carroll, K. M., & Onken, L. S. (2001). A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage 1. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.8.2.133

Ryan, J., McCallion, P., McCarron, M., Luus, R., & Burke, E. A. (2021). Overweight/obesity and chronic health conditions in older people with intellectual disability in Ireland. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 65(12), 1097–1109. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12900

Sailer, A. B., Miltenberger, R. G., Johnson, B., Zetocha, K., Egemo, K., & Hegstad, H. (2006). Evaluation of a weight loss treatment program for individuals with mild mental retardation. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 28(2), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1300/J019v28n02_02

Same, R. V., Feldman, D. I., Shah, N., Martin, S. S., Al Rifai, M., Blaha, M. J., Graham, G., & Ahmed, H. M. (2016). Relationship between sedentary behavior and cardiovascular risk. Current Cardiology Reports, 18(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-015-0678-5

Sari, H. Y., Yılmaz, M., Serin, E., Kısa, S. S., Yesiltep, Ö., Tokem, Y., & Rowley, H. (2016). Obesity and hypertension in adolescents and adults with intellectual disability. Acta Paulista De Enfermagem, 29(2), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0194201600024

Saunders, R. R., Saunders, M. D., Donnelly, J. E., Smith, B. K., Sullivan, D. K., Guilford, B., & Rondon, M. F. (2011). Evaluation of an approach to weight loss in adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-49.2.103

Shlesinger, A., Bird, F., Duhanyan, K., Harper, J. M., & Luiselli, J. K. (2018). Evaluation of a comprehensive health-wellness intervention on weight and BMI of residential students with neurodevelopmental disorders. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 2(4), 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-018-0081-5

Shogren, K. A., & Raley, S. K. (2022). Self-determination and causal agency theory: Integrating research into practice. Springer.

Shogren, K. A., & Singh, N. N. (2022). Intervening from the “inside out”: Exploring the role of self-determination and mindfulness-based interventions for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 6(2), 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-022-00252-y

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Singh, A. N., Winton, A. S. W., Singh, J., McAleavey, K. M., & Adkins, A. D. (2008a). A mindfulness-based health wellness program for an adolescent with Prader-Willi syndrome. Behavior Modification, 32(2), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507308582

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Singh, A. N., Winton, A. S. W., Singh, J., McAleavey, K. M., Adkins, A. D., & Singh, D. S. J. (2008b). A mindfulness-based health wellness program for managing morbid obesity. Clinical Case Studies, 7(4), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507308582

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Singh, A. N. A., Winton, A. S. W., Singh, A. D., & Singh, J. (2011). A mindfulness-based health wellness program for individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 4(2), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2011.583489

Spanos, D., Melville, C. A., & Hankey, C. R. (2013). Weight management interventions in adults with intellectual disabilities and obesity: A systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition Journal, 12, 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-12-132

Tyrer, F., Dunkley, A. J., Singh, J., Kristunas, C., Khunti, K., Bhaumik, S., Davies, M. J., Yates, T. E., & Gray, L. J. (2019). Multimorbidity and lifestyle factors among adults with intellectual disabilities: A cross-sectional analysis of a UK cohort. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 63(3), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12571

Weisz, J. R., Ng, M. Y., & Bearman, S. K. (2014). Odd couple? Re-envisioning the relation between science and practice in the dissemination-implementation era. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613501307

Willems, M., Waninge, A., Hilgenkamp, T. I. M., van Empelen, P., Krijnen, W. P., van der Schans, C. P., & Melville, C. A. (2018). Effects of lifestyle change interventions for people with intellectual disabilities: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(6), 949–961. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12463

Woolcott, O. O., & Bergman, R. N. (2018). Relative fat mass (RFM) as a new estimator of whole-body fat percentage: A cross-sectional study in American adult individuals. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 10980. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29362-1

Wu, C. L., Lin, J. D., Hu, J., Yen, C. F., Yen, C. T., Chou, Y. L., & Wu, P. H. (2010). The effectiveness of healthy physical fitness programs on people with intellectual disabilities living in a disability institution: Six-month short-term effect. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(3), 713–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2010.01.013

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge with thanks all participants who participated in the study.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rachel E. Myers: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation. Oleg N. Medvedev: data analyses, validation, writing–reviewing and editing. Jisun Oh: conceptualization, methodology, writing—reviewing and editing. Karrie A. Shogren: conceptualization, methodology, writing—reviewing and editing. Giulio E. Lancioni: conceptualization, methodology, writing—reviewing and editing. Nirbhay N. Singh: conceptualization, supervision, methodology, data curation, investigation, writing—reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Myers, R.E., Medvedev, O.N., Oh, J. et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Telehealth Family-Delivered Mindfulness-Based Health Wellness (MBHW) Program for Self-Management of Weight by Adolescents with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Mindfulness 14, 524–537 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02085-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02085-9