Abstract

Objectives

Research interest in mindfulness, the capacity for present-oriented, nonjudgmental attention and awareness, and its relation to parenting has been growing in recent years. However, factors facilitating the association between mindfulness and parenting are not yet well understood. In the present study, we examined whether parents’ biased causal thinking about children’s misbehaviors, i.e., parental attributions, may mediate the link between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and parenting. Given that parents of children with clinically elevated mental health difficulties tend to report more biased parental attributions, we further examined whether the proposed mediation may differ across parents of children with and without clinical diagnoses or referrals for mental health difficulties.

Methods

Parents (59.8% mothers) of 8- to 12-year-old children with (n = 157) and without (n = 99) clinical diagnoses or referrals for mental health difficulties participated in online surveys assessing their mindfulness, parental attributions, and negative parenting behaviors.

Results

More mindful parents reported less negative parenting, with the link significantly mediated by less biased parent-directed attributions, but not child-directed attributions. The mediating effect via parent-directed attributions was significantly moderated by the child’s clinical status: the effect was retained only for parents of children with clinical diagnoses or referrals for mental health difficulties. No significant moderation effect emerged for child-directed attributions.

Conclusions

The results provide initial support for the links among parents’ mindfulness, parental attributions, and parenting. The present findings suggest that parental mindfulness may be important for less biased parental attributions, with implications for parenting behaviors at least in the context of children’s mental health disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Parents’ cognitions about their parenting and the causes of their children’s behavior have been the subject of numerous studies because of their key influence on parenting behaviors and, ultimately, children’s emotional and behavioral functioning (Johnston et al., 2018). One important and understudied factor that may be closely associated with parental cognitions is mindfulness. Mindfulness is the quality of consciousness marked by present-oriented attention and awareness without self-judgment of internal experiences (Baer et al., 2006). Individuals high in mindfulness have been shown to demonstrate heightened attention- and emotion-regulation skills as well as elevated positive regard for others as demonstrated through empathic responding and prosocial behavior (Dekeyser et al., 2008; Donald et al., 2019).

In the context of parenting, dispositional mindfulness, or the cognitive tendency to be mindful, has been researched in relation to parenting behaviors and children’s outcomes (Baer et al., 2006; Corthorn & Milicic, 2016). Researchers posit that parents who have generally high levels of dispositional mindfulness, which applies to contexts beyond parenting, are better able to demonstrate more positive and less negative parenting behavior (Parent et al., 2016). This assertion is supported by studies showing that parents with high levels of dispositional mindfulness tend to use more warm and responsive and less harsh and inconsistent parenting, ultimately linking to children’s well-being and positive development (Corthorn & Milicic, 2016; Gouveia et al., 2016; Siu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2019). Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis examining the link between parents’ mindful tendencies (e.g., attentive awareness, acceptance) and parenting found that mindfulness was correlated with less parental stress, laxness, and harshness in parenting across studies (Daks & Rogge, 2020). Another meta-analysis of 30 studies focusing on parents’ dispositional mindfulness and parenting also found that the correlation between dispositional mindfulness and negative parenting behaviors (overreactivity, harshness, parental anger) was similar in strength across parents of clinical and community samples of children (Kil, Antonacci, et al., 2021b). A recent longitudinal study with a community sample of parents demonstrated similar patterns: parents who were high in dispositional mindfulness reported using less negative (and more positive) parenting behavior over time, which in turn predicted less child internalizing and externalizing difficulties several months later (Parent et al., 2021).

While the link between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and parenting has been explored, only a handful of studies have examined its underlying mechanisms, or specific factors that may mediate their link. These studies have examined factors related to parenting as key mediators in the mindfulness and parenting behavior link, including interparental relationship quality and heightened mindful parenting (i.e., the use of mindfulness skills during parent–child interactions; Gouveia et al., 2016; Parent et al., 2016). Of particular relevance, cognitive factors such as parental stress and depressive symptoms appear to be important mediators (Campbell et al., 2017; Parent et al., 2010). For example, Campbell et al. (2017) found that parents’ lower stress during parent–child interactions accounted for the link between higher levels of dispositional mindfulness and better parental responsivity and sensitivity during childrearing.

Building upon studies linking dispositional mindfulness and cognitive factors with parenting behavior, in the present study, we propose that one mediator in the link between mindfulness and parenting may be parents’ cognitions about why children behave the way they do, i.e., parental attributions (Bugental & Johnston, 2000). Parental attributions have been classified into two domains: parent-directed or child-directed (Snarr et al., 2009). Biased parent-directed attributions reflect parents’ self-judgment that they lack parenting skills, while biased child-directed attributions reflect parents’ perceptions that their children are intentionally and purposefully misbehaving and are perhaps to blame for their behavioral difficulties.

The assertion that parental attributions may mediate between dispositional mindfulness and parenting is made based on a number of lines of evidence. First, the broaden-and-build model of mindfulness (Garland et al., 2015) posits that heightened mindfulness propels both self-compassion and other-oriented compassion, even in the face of negative experiences. Following this framework, parents who are high in dispositional mindfulness may be cognitively equipped to accept themselves in a self-compassionate way, and be less biased in their parent-directed attributions. Research supporting this assertion demonstrates that adults with high levels of mindfulness tend to report greater self-acceptance, even of negative characteristics (Pepping et al., 2013; Randal et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015). Such self-acceptance may propel fewer self-blaming attributions such as parent-directed attributions. In support of this hypothesis, Lippold et al. (2019) found in their prospective intervention study on parents of children 10 to 14 years of age that parents who used more mindfulness in parenting at the beginning of the study were less biased in their parent-directed attributions 8 weeks later, regardless of whether they spent those 8 weeks in a parenting intervention or in a control condition. Additionally, although not directly related to parenting contexts, correlational and intervention research on mindfulness in the context of anxiety and depression has similarly shown that individuals who are more mindful report fewer negative judgments about themselves and their perceived flaws (Goyer et al., 2022; Van Dam et al., 2014). Based on these studies, we may expect an association between higher dispositional mindfulness and less biased parent-directed attributions.

Turning to the other-oriented compassion proposed in the broaden-and-build model, parents who are high in dispositional mindfulness may be able to sustain positive and empathic regard for others, including their children when they misbehave or do not comply. As such, they may be less biased in their child-directed attributions. Research supporting this assertion shows that higher dispositional mindfulness is linked to greater interpersonal sensitivity, marked by empathy, perspective-taking, and prosocial behavior (Z. Chen et al., 2020; Dekeyser et al., 2008; Donald et al., 2019). Mindfulness-based intervention studies with individuals and couples have echoed these findings, reporting increased mindreading, acceptance, and heightened empathy following the interventions (Carson et al., 2004; Kappen et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2014). Thus, parents who are high in mindfulness may be expected to hold such other-oriented compassion during interactions with their children, taking their perspective and giving benefit of the doubt, even when they show challenging behaviors. Overall, based on this collective evidence, it may be expected that parents who are high in dispositional mindfulness may hold fewer parent-directed and child-directed attributions regarding their children’s difficult behavior.

As a second line of evidence supporting the hypothesized mediation, it is well established that parental attributions and parenting are linked. Johnston and Ohan (2005) have proposed that parental attributions for child behavior guide discipline practices and parenting responses in caregiving. A number of studies have supported this assertion, demonstrating that parents who hold biased parent-directed and child-directed attributions are more likely to endorse negative and less effective parenting practices (see Bugental & Corpuz, 2019; Johnston et al., 2018). However, in our hypothesized model, parental attributions may also be differentially associated with mindfulness and parenting behavior depending on whether children show elevated emotional or behavioral problems. For example, for parent-directed attributions, two studies on parents of children without clinically elevated difficulties have shown that parents holding more biased parent-directed attributions may use more lax parenting (Leung & Slep, 2006; Slep & O’Leary, 1998). However, other community-sampled parents have demonstrated no relation between parent-directed attributions and harsh or lax parenting (e.g., Smith & O’Leary, 1995). Meanwhile, for parents of children with disruptive behavior, those who hold more biased parent-directed attributions have been shown to use less positive parenting but more inconsistent discipline (Kil et al., 2020). In the context of child internalizing behaviors as well, biased parent-directed attributions have been linked to higher rates of child internalizing problems (Colalillo et al., 2015; Laskey & Cartwright‐Hatton, 2009). Thus, there is initial evidence to support that the extent to which biased parent-directed attributions are present may depend on whether children experience clinically elevated difficulties in mental health.

On the other hand, research on child-directed attributions has found that parents holding more biased child-directed attributions tend to use more harsh, intrusive, and overreactive parenting, and report greater anger about the child’s behavior (Kil, Aitken, et al., 2021a; Slep & O’Leary, 1998; Wagner et al., 2018). Additionally, child-directed attributions appear to be especially elevated in parents of children with clinically elevated behavioral difficulties (MacBrayer et al., 2003) and emotional problems such as anxiety (Sheeber et al., 2009). Even in community samples, parents who hold highly biased child-directed attributions have been found to report heightened externalizing (Nix et al., 1999; Snyder et al., 2005) and internalizing problems in their children (M. Chen et al., 2009). Indeed, these links between biased child-directed attributions, negative parenting, and elevated child mental health difficulties have been replicated in longitudinal studies (Johnston et al., 2009; Wagner et al., 2018). Thus, the body of evidence on child-directed attributions demonstrates consistent links between more biased attributions and heightened child emotional and behavioral difficulties. Overall, parents of children with clinically elevated levels of mental health difficulties may hold more biased parent- and child-directed attributions compared to parents of children without difficulties.

While the links between parenting and either mindfulness or parental attributions have been demonstrated in some samples, it remains unclear whether parental attributions may account for (i.e., mediate) the association between dispositional mindfulness and parenting behavior. Thus, our primary research aim was to examine whether parents’ tendency to make less biased parent- and child-directed attributions may mediate the association between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and their parenting behavior. We hypothesized that less biased parent- and child-directed attributions would mediate the association between higher levels of dispositional mindfulness and less negative parenting. Additionally, based on the literature reviewed above on differences in parental attributions and parenting across parents of children with and without clinically elevated difficulties, we expected that the hypothesized mediation may differ across these samples. Specifically, we hypothesized that the mediation effect would be stronger for parents of children with clinical diagnoses and those referred for mental health treatment than for parents of children without clinically elevated difficulties.

Method

Participants

Participants were 256 parents of children between 8 and 12 years of age. Of these, 157 were parents of children who had received clinical diagnoses or had been referred for mental health services because of elevated internalizing or externalizing problems, and 99 were parents of children who had not received any clinical diagnoses or referrals. Parent demographics by child clinical status are presented in Table 1.

Procedures

Participants were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) website. MTurk is a frequently used crowdsourcing platform in psychological research (Mason & Suri, 2012). On MTurk, potential participants browse available studies for participation, and if they meet inclusion criteria, they can self-enroll and complete participation for a small payment. For the present study, inclusion was restricted to participants who were parents, lived in Canada or the USA, and had a task approval rate over 95% on the platform. All parents consented to participation prior to beginning the survey. Participants were paid $5 USD for completing the survey. Study procedures were approved by the Ethics Board at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Canada.

Measures

Mindfulness

We assessed dispositional mindfulness in parents using the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-15 (FFMQ-15; Gu et al., 2016). A shorter form of the 39-item FFMQ (Baer et al., 2006), the FFMQ-15 includes a total of 15 items that target five facets of mindfulness: observing (e.g., I pay attention to sensations, such as the wind in my hair or sun on my face), describing (e.g., I’m good at finding words to describe my feelings), acting with awareness (e.g., I do jobs or tasks automatically without being aware of what I’m doing, reverse scored), nonjudgment (e.g., I believe some of my thoughts are abnormal or bad and I shouldn’t think that way, reverse scored), and nonreactivity (e.g., When I have distressing thoughts or images I just notice them and let them go). Responses across items are summed for an overall score of mindfulness, with higher values indicating higher levels of mindfulness. The FFMQ variants have been validated in parents of children of varying ages and clinical diagnoses (e.g., de Bruin et al., 2015; Kil & Grusec, 2020). Using the 15-item scale, interitem consistency as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha (α) for parents of children without clinical status was lower than expected, α = 0.66. Further investigation of the item-total statistics revealed low corrected item-total correlations, r = 0.08 and 0.04, respectively, for the nonjudgment items “When I have distressing thoughts or images, I ‘step back’ and am aware of the thought or image without getting taken over by it” and “When I have distressing thoughts or images I am able just to notice them without reacting,” in the parents of children without clinical status group. Omitting these items from both samples improved interitem consistency, as seen in Table 2. This 13-item scale was thus used for the present study. Descriptive statistics, reliability, and consistency for measures of interest are provided in Table 2.

Parental Attributions

We assessed parental attributions using the Parenting Cognition Scale (PCS; Snarr et al., 2009). Two subscales are derived: seven items target parent-directed attributions (e.g., I’m not structured enough with my child), and nine items target child-directed attributions (e.g., My child purposely tries to get me angry). Responses across items are summed by subscale, with higher values indicating more biased parental attributions. The scale has been validated for use with parents of children with and without clinical diagnoses (Snarr et al., 2009; Lysenko et al., 2021).

Negative Parenting

We assessed negative parenting using the Parenting Scale (Arnold et al., 1993). In the scale, 11 items target laxness (e.g., When I say my child can’t do something, I let my child do it anyway), and 10 items target overreactivity (e.g., After there’s been a problem with my child, I often hold a grudge). Although an additional subscale of verbosity exists, it has been found to show problematic reliability and validity (Salari et al., 2012) and thus is not included in this study. An overall negative parenting score was calculated by summing 21 items from laxness and overreactivity, with higher scores indicating more negative parenting. The PS has been validated for use with parents of children with and without clinical diagnoses (Freeman & DeCourcey, 2007; Rhoades & O’Leary, 2007).

Data Analyses

Data were first cleaned for quality due to collection via MTurk (see Chmielewski & Kucker, 2020). Participants who were deemed to have completed the online questionnaire too quickly (less than 8 min) were excluded from the dataset (n = 28). All variables were then standardized. In order to assess all hypotheses in a parsimonious model, we used PROCESS (Hayes, 2017) in SPSS to test for moderated multiple mediation. The moderator of child clinical status was coded using parents’ responses to a single question of whether their children did or did not have a diagnosis or clinic-referral for emotional or behavioral difficulties (1 = Yes, 2 = No). Child age, child sex, and parent gender were controlled in the model. Direct, indirect, and moderated indirect estimates were obtained through PROCESS. Bootstrapping at 10,000 samples was used to obtain 95% confidence intervals. Confidence intervals that do not cross zero are indicative of a significant estimate (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Results

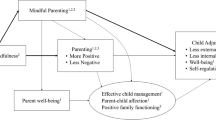

Correlations among the variables of interest are depicted in Table 2, and results of the moderated mediation model are presented in Table 3. As seen in Fig. 1, parents who reported higher levels of dispositional mindfulness reported less negative parenting. Parents who had higher levels of dispositional mindfulness were also less likely to hold biased parent-directed attributions, which in turn associated with less negative parenting. A significant mediation effect was found, such that less biased parent-directed attributions mediated the association between mindfulness and negative parenting. Furthermore, this mediation was significantly moderated by the child’s clinical status on the path between parent-directed attributions and negative parenting, as depicted in Table 4. That is, for parents of children clinic referred for or diagnosed with mental health difficulties, parent-directed attributions were positively associated with negative parenting behavior, which mediated the link between greater mindfulness and less negative parenting, as seen in Fig. 2. This mediation effect was not significant for parents of children without clinically elevated difficulties, however.

On the other hand, parents’ dispositional mindfulness levels were unrelated to child-directed attributions, although more biased child-directed attributions were associated with less negative parenting. The path between child-directed attributions and negative parenting was moderated by the child’s clinical status. That is, for parents of children without any clinic referrals or diagnoses, higher child-directed attributions were linked to more negative parenting. Meanwhile, for parents of children with clinic referrals or diagnoses, there was no significant link between child-directed attributions and negative parenting, although the trend was negative. The link between dispositional mindfulness and negative parenting was not mediated by child-directed attributions, and the moderated mediation was not significant. However, there was a significant difference in the moderated mediation effects for parents of children with vs. without clinical referrals or diagnoses, as depicted in Table 4.

Discussion

With increasing evidence of important associations between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and more positive, less negative parenting, there is a need to understand the mechanisms underlying this link. The present study assessed the mediating role of parental attributions on the link between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and parenting behavior. Findings demonstrated a direct association between greater mindfulness and less negative parenting, echoing numerous existing works. An indirect association also emerged, through parent-directed attributions: in line with our first hypothesis, parents who were more mindful tended to hold less biased parent-directed attributions, which in turn linked to less negative parenting. That parents with high levels of dispositional mindfulness tended not to attribute their children’s negative behaviors to their own parenting is in line with findings by Lippold et al. (2019), which found that parents who were mindful in their parenting behaviors made fewer parent-directed attributions over time. Building on these previous findings, our data suggest that, beyond mindful parenting skills, parents who have a cognitive capacity for mindfulness may also be less likely to attribute child misbehavior to their own lack of parenting skills. The findings also extend on the broaden-and-build model of mindfulness with a contextual lens on parenting, suggesting that parents who are highly mindful tend to be self-accepting and may reappraise difficult parenting situations in a self-compassionate manner.

On the other hand, child-directed attributions did not mediate the link between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and parenting behavior. We had hypothesized that parents who had higher levels of mindfulness may be more compassionate and empathetic to others, including their children. However, the present findings suggest that parents’ mindfulness may be unrelated to whether they attribute the cause of their children’s behavior to internal or purposeful child characteristics. Furthermore, this link was nonsignificant regardless of the child’s clinical status. One potential explanation for this unexpected finding may be that parents who have high dispositional mindfulness are not necessarily using mindfulness in their interactions with others. The FFMQ used in the present study captured parents’ dispositional mindfulness and related cognitive and affective regulatory skills, rather than the use of mindfulness skills in parenting. It has been shown that mindfulness skills facilitate interpersonal sensitivity (e.g., Berry & Brown, 2017). However, mindfulness skills applied to the interpersonal context—mindful parenting, for example, which embodies compassion and acceptance towards the child—may be more closely related to other-oriented thought processes such as child-directed attributions. Indeed, engaging in child-focused interpersonal mindfulness, i.e., mindful parenting, may be associated with engaging in fewer maladaptive child-directed attributions, particularly in the context of child mental health disorders that are considered to be uncontrollable by the child. It remains to be seen whether dispositional versus interpersonal forms of mindfulness may differently link to parent-directed and child-directed parental attributions, as well as whether this link differs across child clinical status.

In line with our second hypothesis, for parents of children with clinical diagnoses or clinic-referred for mental health difficulties, high levels of dispositional mindfulness were associated with less biased parent-directed attributions, and in turn, less negative parenting. This finding extends on knowledge of the associations between parent-directed attributions and parenting in extant literature, which has not been fully consistent (Leung & Slep, 2006; Slep & O’Leary, 1998). The present findings suggest that the parenting behaviors of parents of children with elevated mental health difficulties may be linked to their biased parent-directed attributions. It is possible that parents of children with elevated emotional and behavioral challenges may experience elevated parenting stress and negative emotional responses about parenting (Barroso et al., 2018; Vaughan et al., 2013), which may in turn contribute to diminished confidence in their parenting (Bogenschneider et al., 1997; Sevigny & Loutzenhiser, 2010), as well as negative parenting cognitions and behaviors. Additionally, it may be that these parents of children with mental health disorders themselves have mental health difficulties—i.e., demonstrating intergenerational transmission (Reck et al., 2016; Thornberry et al., 2003). Mental health disorders in parents may be associated with more negative thinking patterns, such as rumination, and lack of confidence about parenting skills (e.g., Dix & Meunier, 2009). However, further work is needed to clarify whether stress, parental mental health needs, or other factors indeed drive the inconsistencies in parent-directed attributions and parenting found in existing literature.

Although child-directed attributions did not mediate the link between parent mindfulness and parenting, and no significant moderated mediation emerged, biased child-directed attributions were related to more negative parenting for parents of children without clinical diagnoses or referrals for mental health difficulties. The finding is in line with previous work on families of children from community samples. Snarr et al. (2009) found in a community sample of parents of children without mental health difficulties that more biased child-directed attributions were correlated with more overreactive, lax, and aggressive parenting (Snarr et al., 2009). Similarly, other work has demonstrated that parents’ biased child-directed attributions are linked to harsher parenting of children without diagnosed difficulties, at least when those parents experience high stress (in the form of working memory load; Sturge-Apple et al., 2014). Borrowing from this latter study, since data collection for the present study took place during the first summer of the coronavirus pandemic, it is especially possible that parents may have been experiencing high levels of stress (Achterberg et al., 2021), with spillover into attributional style and parenting.

The lack of a significant association between child-directed attributions and negative parenting for those parents of children who are clinically involved is surprising. Past research appears to support a positive and significant association, with parents of children with elevated behavioral and attentional difficulties tending to ascribe more biased child-directed attributions compared to parents of children without such difficulties, and using more negative and power assertive parenting responses in turn (e.g., Dix & Lochman, 1990; Gerdes & Hoza, 2006; Johnston & Freeman, 1997). However, there also exist inconsistencies in past work. Echoing findings from the present study, in parents of clinic-referred children with behavioral difficulties, child-directed attributions have been shown to be unrelated to negative parenting, and surprisingly, positively correlated with positive parenting (Kil et al., 2020). Considering these inconsistencies in the literature, further research is needed to determine other factors that may further clarify how biased child-directed attributions may be linked to more or less negative parenting behaviors, particularly in families of children with elevated mental health difficulties.

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations must be considered in interpreting the present findings. First, the data were self-reported and cross-sectional, leading to a number of potential biases (common method, self-report bias) and lack of directionality in effects (Maxwell & Cole, 2007; Podsakoff et al., 2003). In particular, because the present study tested directionality of effects only based on existing longitudinal evidence, an alternative model in which parents’ mindfulness mediates the link between their attributions and parenting is equally plausible. Additionally, although MTurk is frequently used in psychology research, it has been subject to recent scrutiny for inconsistent data quality across studies (e.g., Chmielewski & Kucker, 2020). Collecting data using standard recruitment methods may be necessary to confirm the present findings. Another concern is that children’s internalizing versus externalizing problems were non-differentiated in our sample. Biased parental attributions appear to be more elevated in parents of children with behavioral than emotional difficulties (Kil et al., 2021a; Sawrikar & Dadds, 2018); thus, assessing domains of child difficulties separately may be useful. Similarly, differentiating diagnosed, treated, and only clinic-referred but not yet assessed clinical samples may be helpful to gain a nuanced understanding of how these links may emerge in diverse clinical contexts. Furthermore, the present parent sample was high in SES, mostly White or European-descent, and mostly married, limiting the generalizability of these findings. Finally, the present study did not assess mindful parenting. Considering work finding that dispositional mindfulness and mindful parenting are highly correlated (Kil et al., 2021b), future work may examine the relative importance and directionality of effects of mindfulness and mindful parenting for parental attributions.

With regard to specific and testable future directions, parental attributions have been implicated as important markers of parents’ treatment readiness and child outcomes following interventions for their children’s mental health difficulties. For example, two recent systematic reviews identified that, across diagnoses, less biased parental attributions may be associated with improvements in children’s behavioral difficulties and treatment engagement (Kil et al., 2021a), and that children’s behavioral outcomes can be enhanced by explicitly highlighting parental attributions within behavioral parent training (Sawrikar & Dadds, 2018). However, we still know little about how to best target biased parental attributions. Although no mindfulness-based parenting interventions have specifically focused on changing parental cognitions, some existing work suggests that such interventions may be successful in reducing biased parental attributions (Townshend et al., 2016). In light of this existing literature and the differential findings for clinical and non-clinical samples in the present study, future research is needed that (1) confirms and further investigates the mechanisms underlying the lack of association between parents’ mindfulness and child-directed attributions, and (2) assesses whether targeting parents’ mindfulness may be effective in reducing their parent-directed attributions and thereby improving treatment-related outcomes in clinical settings.

Overall, the present findings show that parent mindfulness is associated with less biased parent-directed attributions, and that these attributions may be differentially linked to maladaptive parenting skills across parents of children with and without clinically elevated difficulties. While further work is needed to confirm and extend on these findings, the present work serves as a promising foundation for understanding the role of parents’ mindfulness on their causal attributions for child difficulties and their parenting behaviors.

Data Availability

Data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data is not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

References

Achterberg, M., Dobbelaar, S., Boer, O. D., & Crone, E. A. (2021). Perceived stress as mediator for longitudinal effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on wellbeing of parents and children. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–14.

Arnold, D. S., O’Leary, S. G., Wolff, L. S., & Acker, M. M. (1993). The parenting scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 137–144.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45.

Barroso, N. E., Mendez, L., Graziano, P. A., & Bagner, D. M. (2018). Parenting stress through the lens of different clinical groups: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(3), 449–461.

Berry, D. R., & Brown, K. W. (2017). Reducing separateness with presence: How mindfulness catalyzes intergroup prosociality. In J. C. Karremans & E. K. Papies (Eds.), Mindfulness in social psychology (pp. 153–166). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Bogenschneider, K., Small, S. A., & Tsay, J. C. (1997). Child, parent, and contextual influences on perceived parenting competence among parents of adolescents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 345–362.

Bugental, D. B., & Corpuz, R. (2019). Parental attributions. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (pp. 722–761). Routledge.

Bugental, D. B., & Johnston, C. (2000). Parental and child cognitions in the context of the family. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 315–344.

Campbell, K., Thoburn, J. W., & Leonard, H. D. (2017). The mediating effects of stress on the relationship between mindfulness and parental responsiveness. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 6(1), 48–59.

Carson, J. W., Carson, K. M., Gil, K. M., & Baucom, D. H. (2004). Mindfulness-based relationship enhancement. Behavior Therapy, 35(3), 471–494.

Chen, M., Johnston, C., Sheeber, L., & Leve, C. (2009). Parent and adolescent depressive symptoms: The role of parental attributions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(1), 119–130.

Chen, Z., Allen, T. D., & Hou, L. (2020). Mindfulness, empathetic concern, and work-family outcomes: A dyadic analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103402.

Chmielewski, M., & Kucker, S. C. (2020). An MTurk crisis? Shifts in data quality and the impact on study results. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(4), 464–473.

Colalillo, S., Miller, N. V., & Johnston, C. (2015). Mother and father attributions for child misbehavior: Relations to child internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(9), 788–808.

Corthorn, C., & Milicic, N. (2016). Mindfulness and parenting: A correlational study of non-meditating mothers of preschool children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(5), 1672–1683.

Daks, J. S., & Rogge, R. D. (2020). Examining the correlates of psychological flexibility in romantic relationship and familydynamics: A meta-analysis. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 214–238.

de Bruin, E. I., Blom, R., Smit, F. M., van Steensel, F. J., & Bögels, S. M. (2015). MYmind: Mindfulness training for youngsters with autism spectrum disorders and their parents. Autism, 19(8), 906–914.

Dekeyser, M., Raes, F., Leijssen, M., Leysen, S., & Dewulf, D. (2008). Mindfulness skills and interpersonal behaviour. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(5), 1235–1245.

Dix, T., & Lochman, J. E. (1990). Social cognition and negative reactions to children: A comparison of mothers of aggressive and nonaggressive boys. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(4), 418–438.

Dix, T., & Meunier, L. N. (2009). Depressive symptoms and parenting competence: An analysis of 13 regulatory processes. Developmental Review, 29(1), 45–68.

Donald, J. N., Sahdra, B. K., Van Zanden, B., Duineveld, J. J., Atkins, P. W. B., Marshall, S. L., & Ciarrochi, J. (2019). Does your mindfulness benefit others? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the link between mindfulness and prosocial behaviour. British Journal of Psychology, 110(1), 101–125.

Freeman, K. A., & DeCourcey, W. (2007). Further analysis of the discriminate validity of the parenting scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29(3), 169–176.

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2015). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: A process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 26(4), 293–314.

Gerdes, A. C., & Hoza, B. (2006). Maternal attributions, affect, and parenting in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comparison families. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(3), 346–355.

Gouveia, M. J., Carona, C., Canavarro, M. C., & Moreira, H. (2016). Self-compassion and dispositional mindfulness are associated with parenting styles and parenting stress: The mediating role of mindful parenting. Mindfulness, 7(3), 700–712.

Goyer, M. S., McKee, L. G., & Parent, J. (2022). Positive and negative interpretation biases in the relationship between trait mindfulness and depressive symptoms in primarily white emerging adults. Mindfulness, 1–13. Online First

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Crane, C., Barnhofer, T., Karl, A., Cavanagh, K., & Kuyken, W. (2016). Examining the factor structure of the 39-item and 15-item versions of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire before and after mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for people with recurrent depression. Psychological Assessment, 28(7), 791–802.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

Johnston, C., & Freeman, W. (1997). Attributions for child behavior in parents of children without behavior disorders and children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(4), 636.

Johnston, C., Hommersen, P., & Seipp, C. M. (2009). Maternal attributions and child oppositional behavior: A longitudinal study of boys with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 189.

Johnston, C., & Ohan, J. L. (2005). The importance of parental attributions in families of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity and disruptive behavior disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8(3), 167–182.

Johnston, C., Park, J. L., & Miller, N. V. (2018). Parental cognitions: Relations to parenting and child behavior. In M. R. Sanders & A. Morawska (Eds.), Handbook of parenting and child development across the lifespan (pp. 395–414). Springer.

Kappen, G., Karremans, J. C., & Burk, W. J. (2019). Effects of a short online mindfulness intervention on relationship satisfaction and partner acceptance: The moderating role of trait mindfulness. Mindfulness, 10(10), 2186–2199.

Kil, H., & Grusec, J. E. (2020). Links among mothers’ dispositional mindfulness, stress, perspective-taking, and mother-child interactions. Mindfulness, 11(7), 1710–1722.

Kil, H., Aitken, M., Henry, S., Hoxha, O., Rodak, T., Bennett, K., & Andrade, B. F. (2021a). Transdiagnostic associations among parental attributions, child behavior and psychosocial treatment outcomes: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1–27.

Kil, H., Antonacci, R., Shukla, S., & De Luca, A. (2021b). Mindfulness and parenting: A meta-analysis and an exploratory meta-mediation. Mindfulness, 1–20.

Kil, H., Martini, J., & Andrade, B. F. (2020). Parental attributions, parenting skills, and readiness for treatment in parents of children with disruptive behavior. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 42, 464–474.

Laskey, B. J., & Cartwright-Hatton, S. (2009). Parental discipline behaviours and beliefs about their child: Associations with child internalizing and mediation relationships. Child Care Health and Development, 35(5), 717–727.

Leung, D. W., & Slep, A. M. S. (2006). Predicting inept discipline: The role of parental depressive symptoms, anger, and attributions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 524.

Lippold, M. A., Jensen, T. M., Duncan, L. G., Nix, R. L., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2019). Mindful parenting, parenting cognitions, and parent-youth communication: Bidirectional linkages and mediational processes. Mindfulness, 1–11.

Lysenko, M., Kil, H., Propp, L., & Andrade, B. F. (2021). Psychometric properties of the parent cognition scale in a clinical sample of parents of children with disruptive behavior. Behavior Therapy, 52(1), 99–109.

MacBrayer, E. K., Milich, R., & Hundley, M. (2003). Attributional biases in aggressive children and their mothers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 698.

Mason, W., & Suri, S. (2012). Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods, 44(1), 1–23.

Maxwell, S. E., & Cole, D. A. (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 23.

Nix, R. L., Pinderhughes, E. E., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., & McFadyen-Ketchum, S. A. (1999). The relation between mothers’ hostile attribution tendencies and children’s externalizing behavior problems: The mediating role of mothers’ harsh discipline practices. Child Development, 70(4), 896–909.

Parent, J., Dale, C. F., McKee, L. G., & Sullivan, A. D. W. (2021). The longitudinal influence of caregiver dispositional mindful attention on mindful parenting, parenting practices, and youth psychopathology. Mindfulness, 12, 357–369.

Parent, J., Garai, E., Forehand, R., Roland, E., Potts, J., Haker, K., Champion, J. E., & Compas, B. E. (2010). Parent mindfulness and child outcome: The roles of parent depressive symptoms and parenting. Mindfulness, 1(4), 254–264.

Parent, J., McKee, L. G., Rough, J. N., & Forehand, R. (2016). The association of parent mindfulness with parenting and youth psychopathology across three developmental stages. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 191–202.

Pepping, C. A., O’Donovan, A., & Davis, P. J. (2013). The positive effects of mindfulness on self-esteem. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(5), 376–386.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In A. F. Hayes, M. D. Slater, & L. B. Snyder (Eds.), The SAGE sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research (pp. 13–54). Sage.

Randal, C., Pratt, D., & Bucci, S. (2015). Mindfulness and self-esteem: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1366–1378.

Reck, C., Nonnenmacher, N., & Zietlow, A.-L. (2016). Intergenerational transmission of internalizing behavior: The role of maternal psychopathology, child responsiveness and maternal attachment style insecurity. Psychopathology, 49(4), 277–284.

Rhoades, K. A., & O’Leary, S. G. (2007). Factor structure and validity of the parenting scale. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(2), 137–146.

Salari, R., Terreros, C., & Sarkadi, A. (2012). Parenting scale: Which version should we use? Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34(2), 268–281.

Sawrikar, V., & Dadds, M. (2018). What role for parental attributions in parenting interventions for child conduct problems? Advances from research into practice. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(1), 41–56.

Sevigny, P. R., & Loutzenhiser, L. (2010). Predictors of parenting self‐efficacy in mothers and fathers of toddlers. Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(2), 179–189.

Sheeber, L. B., Johnston, C., Chen, M., Leve, C., Hops, H., & Davis, B. (2009). Mothers’ and fathers’ attributions for adolescent behavior: An examination in families of depressed, subdiagnostic, and nondepressed youth. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(6), 871–881.

Siu, A. F. Y., Ma, Y., & Chui, F. W. Y. (2016). Maternal mindfulness and child social behavior: The mediating role of the mother-child relationship. Mindfulness, 7(3), 577–583.

Slep, A. M. S., & O’Leary, S. G. (1998). The effects of maternal attributions on parenting: An experimental analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 12(2), 234.

Smith, A. M., & O’Leary, S. G. (1995). Attributions and arousal as predictors of maternal discipline. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19(4), 459–471.

Snarr, J. D., Slep, A. M. S., & Grande, V. P. (2009). Validation of a new self-report measure of parental attributions. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 390–401.

Snyder, J., Cramer, A., Afrank, J., & Patterson, G. R. (2005). The contributions of ineffective discipline and parental hostile attributions of child misbehavior to the development of conduct problems at home and school. Developmental Psychology, 41(1), 30–41.

Sturge-Apple, M. L., Suor, J. H., & Skibo, M. A. (2014). Maternal child-centered attributions and harsh discipline: The moderating role of maternal working memory across socioeconomic contexts. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(5), 645.

Tan, L. B. G., Lo, B. C. Y., & Macrae, C. N. (2014). Brief mindfulness meditation improves mental state attribution and empathizing. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e110510.

Thornberry, T. P., Freeman-Gallant, A., Lizotte, A. J., Krohn, M. D., & Smith, C. A. (2003). Linked lives: The intergenerational transmission of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(2), 171–184.

Townshend, K., Jordan, Z., Stephenson, M., & Tsey, K. (2016). The effectiveness of mindful parenting programs in promoting parents’ and children’s wellbeing: A systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 14(3), 139–180.

Van Dam, N. T., Hobkirk, A. L., Sheppard, S. C., Aviles-Andrews, R., & Earleywine, M. (2014). How does mindfulness reduce anxiety, depression, and stress? An exploratory examination of change processes in wait-list controlled mindfulness meditation training. Mindfulness, 5(5), 574–588.

Vaughan, E. L., Feinn, R., Bernard, S., Brereton, M., & Kaufman, J. S. (2013). Relationships between child emotional and behavioral symptoms and caregiver strain and parenting stress. Journal of Family Issues, 34(4), 534–556.

Wagner, N. J., Gueron-Sela, N., Bedford, R., & Propper, C. (2018). Maternal attributions of infant behavior and parenting in toddlerhood predict teacher-rated internalizing problems in childhood. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(sup1), S569–S577.

Xu, W., Rodriguez, M. A., Zhang, Q., & Liu, X. (2015). The mediating effect of self-acceptance in the relationship between mindfulness and peace of mind. Mindfulness, 6(4), 797–802.

Zhang, W., Wang, M., & Ying, L. (2019). Parental mindfulness and preschool children’s emotion regulation: The role of mindful parenting and secure parent-child attachment. Mindfulness, 10(12), 2481–2491.

Acknowledgements

The authors express thanks to the parents who participated in this study, as well as research assistants who helped with data collection.

Funding

The first author was supported by a Discovery Fund Fellowship from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. The third author was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HK conceptualized the study, collected data, conducted formal analysis and investigation, and wrote the initial draft. SS contributed to data collection, writing the initial draft, and reviewing and editing. BFA contributed to study conceptualization and reviewing and editing the paper, and supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study’s procedures have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kil, H., Shukla, S. & Andrade, B.F. Mindfulness, Parental Attributions, and Parenting: the Moderating Role of Child Mental Health. Mindfulness 13, 1782–1792 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01916-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01916-5