Abstract

Objectives

Loving-kindness meditation (LKM) has been shown to improve wellbeing and positive emotions in clinical and non-clinical populations. The main goal of the present study was to examine whether LKM might be an effective intervention to promote positive mental health using the Positive Mental Health Scale (PMH) and to decrease depression, anxiety, and stress in university students.

Methods

The sample (n = 110) consisted of university students in Germany. One half of them (n = 55) underwent LKM intervention. They were compared with a matched control group (n = 55) which did not receive treatment. All participants completed positive and negative mental health measures at baseline and 1-year follow-up assessments. LKM participants additionally completed the same measures before and after treatment. Multiple analyses of variance were conducted to test for short- and long-term effects of LKM on positive and negative mental health measures.

Results

A significant short-term effect of LKM on anxiety and PMH was found. Long-term analyses revealed a significant decrease of depression, anxiety, and stress for LKM completers, and a significant increase of depression, anxiety, and stress for the control group.

Conclusions

The results suggest that LKM enhances mental health in university students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Evidence suggests that college and university students in the USA and a number of other countries (Auerbach et al., 2018; Orygen, 2017) have greater levels of stress and psychopathology than ever before (Lipson et al., 2019). Self-reported diagnoses, especially depression and anxiety disorders, are increasing (Eisenberg et al., 2013), suggesting that mental health problems are a growing public health concern on campuses. In comparison to students not suffering from mental health problems, affected students additionally report poorer relationships with other students and faculty members, less of engagement in campus clubs and activities, and lower grade point average as well as lower rates of graduation (Storrie et al., 2010; Byrd and McKinney, 2012; Keyes et al., 2012; Salzer, 2012).

According to a recent study by the Barmer health insurance company (Grobe et al., 2018) examining German university students, the proportion of 18- to 25-year-olds diagnosed with mental disorders in Germany rose by 38% between 2005 and 2016. Furthermore, about 17% of students corresponding to almost half a million (around 470,000) people, who had previously been regarded as healthy, appeared to be affected by a mental disorder. In particular, depression, anxiety disorders, and panic attacks among young people seem to be on the rise (Grobe et al., 2018). Despite this, only a small minority of students seem to receive adequate treatment for their mental disorders (Auerbach et al., 2016). A lack of psychotherapeutic support, coupled with a fear of stigma, prevents many from accessing the treatment they need (Vidourek et al., 2014). It might, therefore, be useful to implement low-threshold treatments to reach a high number of students.

A meta-analysis by Regehr et al. (2013) identified the effectiveness of various interventions aimed at reducing stress in university students. Their results revealed that cognitive, behavioral, and mindfulness interventions were associated with decreased symptoms of anxiety and lower levels of depression and cortisol (Regehr et al., 2013). Whereas mindfulness-based interventions have successfully been conducted in university settings (Collard et al., 2008; de Vibe et al. 2013, 2015; Halland et al. 2015; Solhaug et al., 2016; Galante et al., 2018), loving-kindness meditation (LKM) has only recently been examined as a potential intervention for university students’ mental health.

Loving-kindness, also known as metta (in Pali), is derived from Buddhism and refers to a mental state of unconditional kind attitudes toward all beings. LKM is centrally related to, and includes the practice of, mindfulness (Hofmann et al., 2011). The core psychological operation is to train to generate one’s kind intentions toward certain targets. Practitioners silently repeat phrases, such as “may you be happy” or “may you be free from suffering” toward targets. Targets change gradually with practice, from easy to difficult: generally beginning with oneself, followed by loved ones, then neutral people, difficult individuals, and finally all beings. LKM exercises are believed not only to broaden attention but also to enhance positive emotions, and lessen negative emotional states (Dalai Lama and Cutler, 1998; Hofmann et al., 2011).

Meta-analyses suggest that LKM interventions improve health and wellbeing more generally, and positive emotions more specifically in clinical and non-clinical populations (Zeng et al., 2015; Galante et al., 2014). For instance, LKM has been shown to enhance daily experiences of positive emotions in working adults (Fredrickson et al., 2008). With regard to university students, only a few studies have examined the effect of LKM on positive emotions (May et al., 2011; May et al., 2014) or connectedness (Aspy and Proeve, 2017). May et al. (2011, 2014), for example, explored the efficacy of a self-training focused on loving-kindness among university students. The authors found increases of positive affect and decreases of negative affect right after meditation practice. LKM might, therefore, be a potentially efficacious and cost-effective intervention to increase mental health in students as it provides a low-threshold treatment without stigmatization, can be conducted in group settings, and can be easily practiced almost everywhere. Researchers have concluded that universities should employ preventive interventions that potentially reach larger groups of students and not merely rely on individual counseling services (Regehr et al., 2013).

The main goal of the present study was to examine whether LKM might be an effective intervention to promote mental health. Specifically, we hypothesized that participants receiving the LKM intervention will exhibit (1) an increase in positive mental health factors and (2) a decrease in depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. In addition, we aimed to (3) examine whether potential short-term effects endure over a follow-up period of 6 months. The LKM intervention group was not randomized but compared with a matched control group.

Methods

Participants

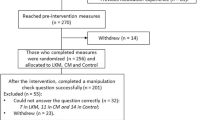

The sample of the present study consisted of participants of the Bochum Optimism and Mental Health (BOOM) program, a cross-sectional and longitudinal study, collecting information about students’ mental health, annually. To assess data, a collective e-mail including a participation invitation and an online-link of the self-report survey is sent to freshmen at our university, who gave permission to be contacted for study participation, at the beginning of winter semester. Data for this study were collected in five subsequent years (2011–2016) in student populations. All students, who completed at least the second online inquiry (n = 540) were offered to participate in LKM. Overall n = 96 (17.7%) students showed general interest in participation, n = 70 of them decided to participate; n = 15 students were not enrolled in the study because they could not make time for the training. Therefore, n = 55 students attended at least one LKM session, n = 5 (9.1%) participants dropped out after the first and second training session, and n = 3 (5.45%) students did not complete the post-LKM assessment. Finally, n = 40 LKM completers (72.72%) took part in the follow-up assessment 6 months after the intervention and 1 year after baseline assessment. Because the purpose of the program was a low-threshold intervention for university students rather than psychotherapy for clinical populations, no exclusion criteria were used and the students were not screened for mental disorders. Age at baseline ranged from 19 to 30 years (M = 22.83, SD= 2.11) and n = 39 (70.9%) of the sample were female. Twenty-five participants (45.5%) were not in a relationship; none of the participants had children. At baseline, the majority (n = 29) of the sample was in their fifth semester of study (M = 5.49, SD = 1.38), and the three most common faculties were Philology, Psychology, and Law.

Among BOOM participants a control group (n = 55) was drawn matching age (M = 22.92, SD = 2.19), gender (70.9% female), semester (M = 5.48, SD = 0.75), and faculty affiliation of the LKM treatment sample. Thirty-eight of them (69.09%) completed the follow-up assessment 1 year after baseline assessment. The conducted power analyses resulted in adequate power for the main associations.

Procedures

After being informed about the procedure of the study, all participants gave written informed consent. As part of the BOOM study, participants completed the below mentioned questionnaires at baseline assessment (time 1) and at follow-up assessment (time 4) 1 year after baseline. In addition to their participation in the BOOM study, LKM participants also completed the above-mentioned questionnaires right before the first session of LKM (time 2), which took place 5 months after baseline, and directly after the last session of LKM intervention (time 3), 5 weeks after time 2. Since the control group did not receive any treatment, they were not tested at time 2 or time 3.

Participants received LKM according to the treatment manual by Totzeck et al. (unpublished manual), based on the LKM manual by Sandra M. Finkel (see Fredrickson et al., 2008). LKM was administered in five group sessions with 3–8 participants per group. The median number of sessions attended was five (M = 4.32, SD = 0.82). All sessions lasted 60 min; they were conducted by one of the four—previously LKM trained—psychologists (n = 3 female), who were also meditation experienced trainers, and supervised by a licensed psychotherapist. Treatment adherence of the trainers was assessed after each session with a one-item self-report (“I managed to adhere to the manual”) on a scale ranging from 0 (“Not at all”) to 7 (“Totally”). Overall, self-reported treatment adherence was very good (M = 6.01, SD = 0.82).

Each session started with a group meditation (15–25 min), followed by a check on participants’ progress and answering questions (20 min), as well as a presentation about features of the meditation and how to integrate concepts from the workshop into one’s daily life (20 min). At the first session, participants were given a CD that included a short version of LKM meditation (10 min) and they were assigned to practice this recording at home, at least 5 days per week. In each session, all participants were asked whether or not they had managed to practice 5 days per week. During the first week, participants practiced a meditation directing love and kindness toward themselves. During the second week, the meditation added loved ones. During subsequent weeks, the meditation expanded from self to loved ones, to acquaintances, to strangers, and finally, to all living beings. The first meditation lasted 15 min, and the final one lasted 25 min.

Measures

DASS-21

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (Henry and Crawford, 2005) is a 21-item self-report instrument measuring the three negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and tension/stress over the past week using a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (“did not apply to me at all”) to 3 (“applied to me very much or most of the time”). Consistency values for the three DASS subscales were α = .87 for depression (DASS-D), α = .77 for anxiety (DASS-A), and α = .84 for stress (DASS-S) in the current sample.

PMH

The Positive Mental Health Scale (Lukat et al., 2016) assesses emotional and psychological aspects of wellbeing across nine items (e.g., “I enjoy my life.”), rated on a scale ranging from 1 (“do not agree”) to 4 (“agree”), with higher scores indicating greater positive mental health. Unidimensional structure, good convergent and discriminant validity have been demonstrated in various populations (Lukat et al., 2016). Cronbach’s alpha was excellent in this study: α = .91.

SHS

The Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky and Lepper, 1999) is a 4-item scale that assesses global subjective happiness. Two items ask respondents to characterize themselves using both absolute ratings ranging from 1 (“not a very happy person”) to 7 (“a very happy person”) and ratings relative to peers also ranging from 1 (“less happy”) to 7 (“more happy”). Two items of the SHS offer brief descriptions of happy and unhappy individuals and ask respondents the extent to which each characterization describes them from 1 (“not at all”) to 7 (“a great deal”). Convergent and discriminant validity have been confirmed in several studies (e.g., Lyubomirsky, 2001); in the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was also very good: α = .86.

Data Analyses

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 24.0) was used to analyze the research data. In order to investigate baseline differences between LKM and control group, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted using the two groups as between-subjects variables and DASS, PMH, and SHS as dependent variables. Short-term effects of LKM intervention on mental health were examined using a MANOVA with repeated measures: the two experimental times (pre-LKM = time 2 and post-LKM = time 3), served as within-subjects variables and DASS, PMH, and SHS scores as dependent variables. Finally, another MANOVA with repeated measures was conducted to examine long-term effects: baseline (time 1) and follow-up assessment (time 4) served as within-subjects variables; LKM and control group as between-subjects variables; and DASS, PMH, and SHS as dependent variables. Pairwise comparisons between assessments and between groups were computed. Homogeneity of error variances was tested using the Mauchly test for sphericity. In case of significant results of the Mauchly test, a Greenhouse-Geisser correction was conducted. The level of significance was set as p < .05 (two-tailed). Partial η2 was calculated as an estimate of effect size. According to Cohen (1992; 1988) a partial η2 of .01 can be considered small, .06 medium, and .14 large effect.

Results

Baseline Analyses

At baseline, the DASS scores were slightly higher and the PMH and SHS scores were slightly lower in the LKM group as compared with the control group. The MANOVA using the two groups as between-subject variables and DASS, PMH, and SHS as dependent variables resulted in no significant differences (all p values > .07). Baseline results are presented in Table 1.

Short-term Effects of LKM

Between baseline and pre-LKM assessment (time 2) 5 months after baseline, none of the scores changed significantly (all p values > .70). Throughout the LKM intervention, we observed a significant multivariate Time effect (F(1, 46) = 21.54, p < .001; Wilks’ λ = .681; ηp2 = .32). The repeated measures MANOVA from pre- (time 2) and post-intervention (time 3) showed significant changes during the course of LKM only for DASS-Anxiety (F(1, 46) = 10.08, p = .003; Wilks’ λ = .820; ηp2 = .18), and PMH (F(1, 46) = 6.92, p = .012; Wilks’ λ = .869; ηp2 = .13), but not for the other measures (all p values > .08). All mean scores as well as changes between pre- and post-intervention assessment are presented in Table 2.

Long-term Effects of LKM

Results of the repeated measures MANOVA from baseline (time 1) and follow-up (time 4) as the within-subjects factor revealed a significant multivariate Time*Intervention interaction effect (F(1, 76) = 7.87, p = .003; Wilks’ λ = .906; ηp2 = .09). All changes of DASS, PMH, and SHS scores between baseline and follow-up assessment are presented in Table 3.

All three DASS-subscale scores significantly decreased in the LKM intervention group between baseline and follow-up assessment: DASS-D (F(1, 76) = 22.16, p < .001; Wilks’ λ = .774; ηp2 = .23), DASS-A (F(1, 76) = 22.16, p < .001; Wilks’ λ = .774; ηp2 = .23), and DASS-S (F(1, 76) = 11.40, p = .001; Wilks’ λ = .870; ηp2 = .13). Within the control group, none of the three DASS-subscales decreased. Instead, DASS-D (F(1, 76) = 8.20, p = .005; Wilks’ λ = .903; ηp2 = .10) significantly increased. In addition, the DASS-S (F(1, 76) = 4.62, p < .035; Wilks’ λ = .943; ηp2 = .06) also significantly increased within the control group between baseline and follow-up assessment.

With regard to the positive measures, no further significant increase was found: neither in the LKM treatment group, nor in the control group (all p values > .10). However, results did reveal a significant decrease of SHS within the control group (F(1, 76) = 4.95, p = .029; Wilks’ λ = .939; ηp2 = .06).

Finally, the LKM group scored significantly lower than the control group in DASS-D (F(1, 79) = 6.01, p = .016; ηp2 = .07), and DASS-S (F(1, 79) = 4.38, p = .04; ηp2 = .05) at follow-up. Further significant differences were not found (all other p values > .30). An overview about these findings is presented in Fig. 1 a and b.

a Changes of DASS scores of LKM treatment group and control group between baseline and follow-up assessment. DASS, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; numbers represent the four assessment times. *p < .05, **p < .005. The blue lines depict significant changes in the LKM treatment group. b Changes of PMH and SHS scores of LKM treatment group and control group between baseline and follow-up assessment. PMH, Positive Mental Health Scale; SHS, Subjective Happiness Scale; numbers represent the four assessment times. *p < .05

Discussion

The main purpose of the present study was to investigate whether LKM might be an effective intervention to promote mental health in university students: we hypothesized that participants receiving the LKM intervention would show (1) an increase in positive mental health factors as well as (2) a decrease in depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms.

According to the first hypothesis, subjective happiness did not change, whereas positive mental health as assessed using the PMH increased significantly after LKM termination. In addition, results revealed a significant decrease of anxiety scores after LKM participation. However, depression and stress scores did not decrease. Therefore, our second hypothesis was only partially confirmed. These findings are in contrast with previous studies showing a stronger short-term effect of LKM on negative emotions (e.g., Fredrickson et al., 2008; May et al., 2014). However, our intervention was conducted during a very stressful period for the participating students: the majority of them were in their fifth semester of study and, therefore, right before graduation (B. Sc.). This might have provoked increases in stress and depression because further stressful events might have occurred. However, even more surprising though is our finding of a short-term decrease in anxiety symptoms throughout LKM. Similar to other mindfulness-based treatments, the meditation might have caused a relaxation effect leading to the decrease of anxiety symptoms. However, we additionally found a short-term increase of positive mental health after LKM termination suggesting a stronger effect above and beyond relaxation. Positive mental health, as assessed with the PMH, comprises emotional as well as psychological components of wellbeing and indicates positive functioning (Lukat et al., 2016). As mentioned above, positive mental health has been shown to predict the remission of anxiety disorders (Teismann et al., 2018). Taking these findings into account, it is possible that there is a unique interplay between positive mental health and anxiety. Future studies will be needed to investigate this possible association.

Our third aim was to examine whether short-term effects of LKM have enduring effects over a follow-up period of 6 months. Interestingly, all three DASS subscale scores of LKM participants significantly decreased from baseline to follow-up assessment: depression, anxiety, as well as stress levels decreased. With regard to the control group, the opposite effect was found; all three DASS subscale scores increased, including a significant increase in depression and stress scores. These results fit into the picture of previous studies. Encountering new experiences, relationships, and living situations (Byrd and Mckinney, 2012; Lipson et al., 2015) during the university period gives rise to stress experiences that can impact mental health (Soet and Sevig, 2006). Another contributing factor might be the fact that the onset of common mental disorders, such as anxiety or depressive disorders, occurs during late adolescence and early adulthood (Kessler et al., 2007). The university years, therefore, represent a period of increased vulnerability for the development of mental health challenges. Because participants in the present study were advanced students, they were likely confronted with difficult life decisions that might have produced additional stress. Future research should examine whether students show different levels of resilience or vulnerability, depending on how far along they are in their respective study programs. However, the LKM intervention appeared to not only impede the progress of mental health problems but also might have contributed to a more positive mental health of LKM participants when compared with their matched counterparts in the control group. Although previous studies have shown that LKM training can have a significant impact on negative affect in the short term (e.g., Fredrickson et al., 2008), the results of the present study suggested that LKM had no effect on depressive symptoms in the short term, whereas depressive symptoms decreased significantly in the long term. This effect might be partially due to depressive symptoms going beyond the sensation of negative affect. In addition, LKM training might lead to further improvements in daily life, such as closer interpersonal relationships (e.g., Cohn & Fredrickson, 2010) or psychological distress (e.g., Shonin et al., 2015). These improvements might also be associated with a further reduction of depressive symptoms. Further studies are needed to examine these associations in the short and long term.

We allowed every interested students to attend LKM. Although we did not randomize participants to the conditions, the self-selection of students also displays that these students were probably aware of their increasing mental health challenges. At baseline assessment, we did find subclinical scores on the DASS measure. According to the DASS cut-off scores, the mean scores of LKM participants were within the category of “mild depressive” and “mild anxious.” Their acceptance to participate in LKM training, hereby, also represents a search for assistance to enhance mental health.

Limitations and Future Research

First of all, common method biases must be taken into consideration when evaluating the results of the present study. The fact that participants were asked to report their own perceptions on multiple constructs in the same survey might have produced spurious effects due to the nature of the measurement instruments rather than to the constructs being measured. In addition, we did not assess the actual amount of participants’ weekly practice time. Since previous studies reported that there was no significant association between practice time and daily positive emotions in their intervention (e.g., May et al., 2011; Jazaieri et al., 2014), we focused on the information whether or not participants managed to practice at least 5 days per week. However, it remains unclear whether the intensity of practice might influence individual improvement. Furthermore, we cannot determine which part of the LKM intervention might be the effective component. As the meta-analysis by Zeng et al. (2015) already pointed out, several components of LKM might contribute to positive effects. Future research should, therefore, address this question by examining the effect of the single components of LKM.

References

Aspy, D. J., & Proeve, M. (2017). Mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation: effects on connectedness to humanity and to the natural world. Psychological Reports, 120(1), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294116685867.

Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Axinn, W. G., Cuijpers, P., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., et al. (2016). Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 46(14), 2955–2970. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001665.

Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., et al. (2018). WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127, 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000362.

Byrd, D., & McKinney, K. (2012). Individual, interpersonal, and institutional level factors associated with the mental health of college students. Journal of American College Health, 60(3), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2011.584334.

Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power for the behavioural science (2nd ed). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

Cohn, M. A., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2010). In search of durable positive psychology interventions: predictors and consequences of long-term positive behavior change. Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.508883.

Collard, P., Avny, N., & Boniwell, I. (2008). Teaching mindfulness based cognitive therapy (MBCT) to students: the effects of MBCT on the levels of mindfulness and subjective well-being. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 21(4), 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070802602112.

Lama, D., & Cutler, H. (1998). The art of happiness: a handbook for living. Rockland: Compass Press.

Eisenberg, D., Hunt, J., & Speer, N. (2013). Mental health in American colleges and universities: variation across student subgroups and across campuses. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827ab077.

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1045–1062. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013262.

Galante, J., Dufour, G., Vainre, M., Wagner, A. P., Stochl, J., Benton, A., Lathia, N., Howarth, E., & Jones, P. B. (2018). A mindfulness-based intervention to increase resilience to stress in university students (the mindful student study): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Public health, 3(2), e72–e81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30231-1.

Galante, J., Galante, I., Bekkers, M.-J., & Gallacher, J. (2014). Effect of kindness-based meditation on health and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1101–1114. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037249.

Grobe, T. G., Steinmann, S., & Szecsenyi, J. (2018). Barmer medical report (7th edition). Berlin: Barmer

Halland, E., de Vibe, M., Solhaug, I., Tyssen, R., Friborg, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Bjørndal, A. (2015). Mindfulness training improves problem-focused coping in psychology and medical students. College Student Journal, 49(3), 387–398.

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS- 21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657.

Hofmann, S. G., Grossman, P., & Hinton, D. E. (2011). Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: potential for psychological interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 1126–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.003.

Jazaieri, H., McGonigal, K., Jinpa, T., Doty, J. R., Gross, J. J., & Goldin, P. R. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of compassion cultivation training: effects on mindfulness, affect, and emotion regulation. Motivation and Emotion, 38, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-013-9368-z.

Kessler, R. C., Amminger, G. P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Lee, S., & Ustün, T. B. (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(4), 359–364. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c.

Keyes, C. L. M., Eisenberg, D., Perry, G. S., Dube, R. D., Kroenke, S. R., & Dhingra, S. S. (2012). The relationship of level of positive mental health with current mental disorders in predicting suicidal behavior and academic impairment in college students. Journal of American College Health, 60(2), 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2011.608393.

Lipson, S., Gaddis, S., Heinze, J., Beck, K., & Eisenberg, D. (2015). Variations in student mental health and treatment utilization across U.S. colleges and universities. Journal of American College Health, 63(6), 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2015.1040411.

Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E. G., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Services, 70, 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800332.

Lukat, J., Margraf, J., Lutz, R., van der Veld, W. M., & Becker, E. S. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Positive Mental Health Scale (PMH-scale). BMC Psychology, 4, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0111x.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46, 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006824100041.

Lyubomirsky, S. (2001). Why are some people happier than others?: the role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. American Psychologist, 56, 239–249.

May, C. J., Burgard, M., Mena, M., Abbasi, I., Bernhardt, N., Clemens, S., et al. (2011). Short-term training in loving-kindness meditation produces a state, but not a trait, alteration of attention. Mindfulness, 2(3), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0053-6.

May, C. J., Weyker, J. R., Spengel, S. K., Finkler, L. J., & Hendrix, S. E. (2014). Tracking longitudinal changes in affect and mindfulness caused by concentration and loving-kindness meditation with hierarchical linear modeling. Mindfulness, 5(3), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0172-8.

Orygen. (2017). The national centre of excellence in youth mental health. Under the radar. The mental health of Australian university students. Melbourne: Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health.

Regehr, C., Glancy, D., & Pitts, A. (2013). Interventions to reduce stress in university students: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 148, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.026.

Salzer, M. (2012). A comparative study of campus experiences of college students with mental illnesses versus a general college sample. Journal of American College Health, 60(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2011.552537.

Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., Compare, A., et al. (2015). Buddhist-derived loving-kindness and compassion meditation for the treatment of psychopathology: a systematic review. Mindfulness, 6, 1161–1180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0368-1.

Soet, J., & Sevig, T. (2006). Mental health issues facing a diverse sample of college students: results from the college student mental health survey. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 43(3), 410–431. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1676.

Solhaug, I., Eriksen, T. E., de Vibe, M., Haavind, H., Friborg, O., Sørlie, T., & Rosenvinge, J. H. (2016). Medical and psychology student's experiences in learning mindfulness: benefits, paradoxes, and pitfalls. Mindfulness, 7, 838–850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0521-0.

Storrie, K., Ahern, K., & Tuckett, A. (2010). A systematic review: students with mental health problems: a growing problem. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01813.x.

Teismann, T., Brailovskaia, J., Totzeck, C., Wannemüller, A., & Margraf, J. (2018). Predictors of remission from panic disorder, agoraphobia and specific phobia in outpatients receiving exposure therapy: the importance of positive mental health. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 108, 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.06.006.

de Vibe, M., Solhaug, I., Tyssen, R., Friborg, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., Sorlie, T., & Bjørndal, A. (2013). Mindfulness training for stress management: a randomised controlled study of medical and psychology students. BMC Medical Education, 13, 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-107.

de Vibe, M., Solhaug, I., Tyssen, R., Friborg, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., Sorlie, T., Halland, E., & Bjorndal, A. (2015). Does personality moderate the effects of mindfulness training for medical and psychology students? Mindfulness, 6(2), 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0258-y.

Vidourek, R. A., King, K. A., Nabors, L. A., & Merianos, A. L. (2014). Students’ benefits and barriers to mental health help-seeking. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 1009–1022. https://doi.org/10.1080/2F21642850.2014.963586.

Zeng, X., Chiu, C. P. K., Wang, R., Oei, T. P. S., & Leung, F. Y. K. (2015). The effect of loving-kindness meditation on positive emotions: a meta-analytic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1693. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsyg.2015.01693.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Helen Copeland-Vollrath for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. Christina Totzeck received a PhD Scholarship by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation for this project. Stefan G. Hofmann receives financial support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (as part of the Humboldt Prize), NIH/NCCIH (R01AT007257), NIH/NIMH (R01MH099021, U01MH108168), and the James S. McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Initiative in Understanding Human Cognition – Special Initiative. Support by the Alexander von Humboldt Professorship awarded to Jürgen Margraf by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CT: designed and executed the study, conducted the data analyses, and wrote the paper. TT and SGH: collaborated in the writing and editing of the study. RVB: collaborated in the analyses of the data and wrote part of the results. VP and AW: collaborated in the editing of the final manuscript. JM: designed the study and collaborated in the editing of the final manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

After being informed about the procedure of the study, all participants gave written informed consent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Statement

All authors state their compliance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). They also agree to the ethical standards of the Faculty of Psychology’s Ethical Commission of the Ruhr University Bochum. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology at the Ruhr University Bochum.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Totzeck, C., Teismann, T., Hofmann, S.G. et al. Loving-Kindness Meditation Promotes Mental Health in University Students. Mindfulness 11, 1623–1631 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01375-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01375-w