Abstract

Conditional goal setting (CGS, the tendency to regard high order goals such as happiness, as conditional upon the achievement of lower order goals) is observed in individuals with depression and recent research has suggested a link between levels of dispositional mindfulness and conditional goal setting in depressed patients. Since interventions which aim to increase mindfulness through training in meditation are used with patients suffering from depression it is of interest to examine whether such interventions might alter CGS. Study 1 examined the correlation between changes in dispositional mindfulness and changes in CGS over a 3-4 month period in patients participating in a pilot randomised controlled trial of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT). Results indicated that increases in dispositional mindfulness were significantly associated with decreases in CGS, although this effect could not be attributed specifically to the group who had received training in meditation. Study 2 explored the impact of brief periods of either breathing or loving kindness meditation on CGS in 55 healthy participants. Contrary to expectation, a brief period of meditation increased CGS. Further analyses indicated that this effect was restricted to participants low in goal re-engagement ability who were allocated to loving kindness meditation. Longer term changes in dispositional mindfulness are associated with reductions in CGS in patients with depressed mood. However initial reactions to meditation, and in particular loving kindness meditation, may be counterintuitive and further research is required in order to determine the relationship between initial reactions and longer-term benefits of meditation practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interventions which use training in meditation to target psychiatric symptoms have become more and more widespread (e.g., Diodonna 2009), and research has demonstrated their effectiveness in a wide range of conditions (Hoffman et al. 2010). With this development, there is now an increased interest in learning about the mechanisms through which such interventions exert their effects. Knowing about these mechanisms is important to inform the incremental development of mindfulness-based interventions for different patient groups and mirrors developments in psychotherapy research in general, where researchers have become increasingly interested in investigating the course and mechanisms of change (Hayes et al. 2007).

Interestingly, psychotherapy research has shown that change is not always linear (Hayes et al. 2007), but often occurs in a discontinuous manner following episodes of destabilization in which symptoms are likely to show a transient worsening. Such trajectories seem particularly characteristic of treatments that involve elements of exposure—where avoidance is reduced for new learning experiences to become available. Interventions that use mindfulness meditation may produce similar patterns of change since exposure to inner experience is hypothesized to be one of the mechanisms through which they exert their effects. Indeed, the idea of working with hindrances during practice reflects the belief that destabilizing experiences are an important part of the transformative work of meditation.

Clinically, it is important to learn more about discontinuities in psychological change during psychotherapy for two reasons. Firstly, if treatment involves destabilizing effects that are too strong, these effects can easily undermine motivation. There is some evidence to suggest that initial reactions to meditation may be counterintuitive and that in groups with certain cognitive profiles, drop out from meditation-based treatment can be significant. In particular, individuals with a history of depression who are high in brooding appear to respond negatively when initially exposed to loving-kindness meditation (Barnhofer et al. 2010) and to drop out early from mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (Crane and Williams 2010), perhaps because initial experiences of meditation are too challenging. Knowing more about destabilizing effects may help to identify those individuals who are likely to need extra support to engage, who paradoxically might exactly be those who have the most to gain in the long term, and find ways of supporting participants in balancing these challenges. Secondly, research may help to see more clearly the nature of destabilizing effects. This is important since many of the effects of meditation arise in an implicit rather than explicit manner. For example, in our previous research, we have found changes in goal representations following an 8-week meditation course although goals were not addressed explicitly at any point in the course. Our aim in the current studies was to explore discontinuities in change by comparing the initial effects of short guided meditations with effects following several weeks’ practice as part of a mindfulness-based intervention.

Specifically, this paper explores the impact of mindfulness and meditation on self-regulation in relation to important life goals. Goals represent desired states, outcomes, or concepts which structure and guide behavior (e.g., Carver and Scheier 1998). Models of self-regulation typically suggest that goals are organized hierarchically, with abstract high-order goals placed at the top, goals which describe more specific desired outcomes intermediate, and goals which define concrete action steps located at the bottom of the hierarchy (e.g., Martin and Tesser 1989). While some links within the goal hierarchy are essential for successful goal pursuit (e.g., I must attend university on a regular basis in order to achieve the goal of obtaining a degree), it is suggested that individuals differ in the extent to which achievement of very high order, self-defining goals (e.g., happiness, self-worth, and fulfillment) is regarded as contingent on the attainment of particular lower order, more concrete goals. Specifically, Street (2001) introduced the term conditional goal setting (CGS) to refer to the tendency of some people to regard happiness and other similar high-order goals, as pursuable and achievable through attainment of particular lower-order outcomes (e.g., I can only be happy if…. I am financially secure, doing well at work, in a romantic relationship).

The concept of conditional goal setting shares many similarities with the theory of goal linking developed by McIntosh and colleagues (e.g., McIntosh et al. 1995). In both cases, it is suggested that because certain goals are over-valued as routes through which happiness can be achieved, an individual becomes vulnerable to depression. In particular, people who link goals, or set conditional goals, are regarded as being more likely to experience high levels of rumination and negative affect when goal progress falters because threats to even relatively low-order goals have implications for the likelihood of achieving high-order goals (e.g., McIntosh et al. 2009). People may also show a tendency to put happiness on hold, “when I achieve … I will be happy” while particular goals are being pursued which may act to undermine day-to-day well-being (Street 2001).

Consistent with the above suggestions, previous studies have shown that CGS is correlated with symptoms of depression in students (e.g., Street 2001), recently diagnosed cancer patients (Street 2003) and children (Street et al. 2003) as well as with levels of hopelessness amongst people with depression (Hadley and MacLeod 2010). It has also been demonstrated that people who engage in goal linking show higher levels of stress when their goals are challenged (McIntosh 1997). For example, the linking of the goal of biological parenthood to happiness and fulfillment is associated with greater emotional distress in infertile couples (Brothers and Maddux 2003), while dispositional goal linking assessed at a one time point predicts level of depression and physical symptoms in the context of hassles at least 2 weeks later (McIntosh et al. 1995). Finally, those who view their self-esteem as contingent upon particular achievements respond when these achievements are threatened with attempts at self-esteem preservation, at the expense of more productive goal-directed behavior (Crocker et al. 2006), again suggesting that setting conditional or linked goals may undermine optimum self-regulation. These findings together suggest that reducing levels of CGS may be helpful for people in general, and for people who suffer from depression in particular.

Although the factors determining level of conditional goal setting are not well established, recent research suggests that high levels of conditional goal setting are linked to lower levels of dispositional mindfulness in depressed patients (Crane et al. 2010). Dispositional mindfulness can be conceptualized as a trait-like variable, reflecting the extent to which people naturally orient their attention and awareness towards ongoing, moment to moment experiences and bring attitudes of acceptance, self-compassion and non-judgment to these (e.g., Baer et al. 2006, 2008). Although there are likely to be individual differences in trait mindfulness, it is also suggested both within the Buddhist tradition, and by proponents of clinical interventions such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (Kabat-Zinn 1990) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (Segal et al. 2002), that levels of mindfulness can be increased through meditation training.

One possibility is that treatments such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (Segal et al. 2002), which aim to increase levels of mindfulness, may act in part by modifying patients’ conditional goal setting tendencies. For example, Segal et al. argue that mindful awareness enables people to shift from an analytical “doing” mode of mind, dominated by a focus on discrepancies between current states and desired goals, to a more experiential “being” mode of mind, in which present moment experience predominates. In the being mode, which is explicitly cultivated in the meditative state, but which is thought to gradually become more and more available in everyday life with sustained practice, individuals are able to observe their own mental processes from a decentered perspective. Previous research has suggested that increases in dispositional mindfulness are associated with a letting go of maladaptive ideal self guides (Crane et al. 2008). It is plausible that increased mindfulness may also enable individuals to relate more flexibly to conditional goals and gain insight into the maladaptive consequences of conditional goal setting. Indeed, Shapiro et al. (2006) suggest that the cultivation of mindfulness enables individuals to “practice acceptance, kindness & openness even when what is occurring in the field of experience is contrary to deeply held wishes or expectations” (p. 377). This ability to remain open and accepting to the possibility of alternative sources of fulfillment if particular desired goals become unattainable is fundamentally incompatible with conditional goal setting, in which particular goals are seen as the only available path to fulfillment. Thus, cultivating mindfulness may gradually undermine conditional goal setting tendencies.

There are numerous forms of meditation practice. Two of the more commonly researched are mindfulness of breathing and loving-kindness meditation. Mindfulness of breathing is used to cultivate awareness and acceptance of sensory experiences and internal states including thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations. All experiences are accepted, and there is no intention to cultivate a particular emotional state. Loving-kindness meditation, in contrast, focuses on the cultivation of unconditional positive emotional states, such as kindness and compassion, directed both towards the self and towards others Salzberg (2002). Both forms of practice might be expected to have an impact on CGS in the longer term, mindfulness of breathing by increasing individuals’ ability to observe and decenter from their tendency to view happiness as conditional upon particular achievements or goals, and loving-kindness practice by giving individuals direct experience of their ability to cultivate a sense of joy and well-being independently of external circumstances (see Fredrickson et al. 2008, for a study exploring the cumulative effects of loving-kindness practice).

The first study reported here explores the impact of mindfulness training on conditional goal setting. We examined whether a course of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (Segal et al. 2002), which was supplemented by loving-kindness meditation practice towards the end of the course, led to changes in dispositional mindfulness or conditional goal setting over a 3–4-month period. This study used data from a sub-sample of the depressed patients who participated in Crane et al. (2010) and were randomized to a trial of MBCT for chronic/recurrent depression (Barnhofer et al. 2009). We hypothesized that individuals who had received treatment with MBCT would show greater reductions in CGS than those allocated to the waitlist condition and that changes in CGS over the 3–4-month period would be correlated with changes in dispositional mindfulness across the sample as a whole. We present the findings of study 1 below, before turning to study 2, a laboratory-based study that examined the impact of brief periods of meditation on conditional goal setting and the extent to which individual differences in a trait measure of goal-related self-regulation might influence initial responses to meditation practice.

Study 1

Method

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from the community, through media advertising, as well as from local GP practices, local psychologists, and non-statutory organizations providing support for people with depression. Volunteers were requested who were currently feeling depressed, who had also been depressed in the past, and who had suffered from suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

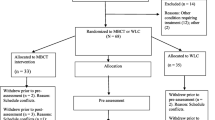

Participants were included in the study if they met current diagnostic criteria for major depression or reported the presence of residual symptoms following a full episode. All participants additionally had either a history of three or more episodes of depression or chronic depression. All had a history of suicidal ideation or behavior. Individuals with bipolar disorder, an eating disorder or OCD, borderline personality disorder, severe alcohol or substance dependence, learning difficulties, or a lack of fluency in written and spoken English were excluded. In total, 90 individuals from Oxfordshire contacted the research team in response to advertisements or as a result of referrals, of whom 31 were found to meet all criteria and requirements. Of those who had entered the trial, three participants withdrew prior to completion of post-treatment assessments, one participant did not provide complete data on the goals task at the baseline assessment, and two provided incomplete data on the measure of dispositional mindfulness. Complete data on the measures of relevance to the current report were therefore available for 25 participants (TAU, n = 11 and MBCT, n = 14). The main clinical outcomes of the trial, concerning change in clinical symptoms from baseline to follow-up, are reported in Barnhofer et al. (2009). The study received ethical approval from the local National Health Service research ethics committee (Ref: 07/Q1607/2).

Relevant Measures

Measure To Elicit Positive Future Goals and Plans (MEPGAP: Hadley and MacLeod 2010; Vincent et al. 2004)

Participants were given 60 s to generate as many goals as they could think of for the coming year in nine different life domains. Goals were defined as “things that you would like to happen or things that you would like to be true of your life in the future.” Participants described each goal, and this was recorded verbatim by the experimenter. Following the goal generation phase, participants reviewed their goals and selected the six most important. These goals were then transferred on to ratings sheets, and participants were asked to rate how likely they thought it was that they would achieve the goal on a scale from 1 (not at all likely) to 9 (extremely likely). For each goal, the participant then made ratings of the extent to which they regarded their happiness, self-worth, and fulfillment as dependent on achievement of the goals listed. For each rating, the respondent then chose which of two statements they agreed most with: “I can only be happy (fulfilled/have a sense of self-worth) if I achieve this goal” or “Even if I do not achieve this goal I can still be happy (fulfilled/have a sense of self-worth),” rating the extent to which they agreed with the chosen statement (“very strongly,” “strongly,” “moderately,” or “slightly”). Responses were re-coded into numerical values, so that very strongly agreeing with the statement “I can only be happy if I achieve this goal” translated into a score of 8, the highest level of conditional goal setting, while very strongly agreeing with the statement “Even if I do not achieve this goal I can still be happy” translated into a score of 1, the lowest level of conditional goal setting. The scores are then summed over the three conditional goal setting measures happiness, fulfillment, and self-worth, to give an overall conditional goal setting score. Each individual goal setting measure, as well as the overall score, has been shown to have high internal reliability (Crane et al. 2010). The task was administered by a research assistant blind to treatment allocation.

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al. 2006)

The 49-item version of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire was employed in this study. The FFMQ measures the following facets of mindfulness: non-reactivity, observing, acting with awareness, describing, and non-judging. Several of the five facets have high incremental validity in predicting psychological symptoms and well-being (Baer et al. 2006; Baer et al. 2008).

Procedure

Participants attended an initial session during which they were assessed by interview and through the completion of a number of self-report questionnaires. Those participants who were eligible for the study were invited to a second assessment session during which they completed several further questionnaires and the goals task. Following the completion of the baseline measures, participants were randomly allocated to either immediate treatment or to a waitlist condition. Those allocated to immediate treatment received an 8-week course of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, modeled very closely on the program outlined in Segal et al. (2002) with minor modifications for the client group, including the addition of a crisis plan and the introduction of loving-kindness meditation in week 6 of treatment. Following treatment, or the comparable waiting period (approximately 3–4 months from baseline to follow-up assessment), all participants who could be contacted were reassessed using the measures administered at the baseline assessment and those in the waitlist condition were offered treatment.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The mean age of the participants (nine males and 16 females) was 41.88 (SD = 10.61, range 26–64), and mean years of education was 15.50 (SD = 3.02, range 11–20). Thirteen participants were married or cohabiting; four were widowed, separated, or divorced; and eight were single. Fifteen participants were working full-time and seven part-time, and three were homemakers. The MBCT (n = 14) and TAU (n = 11) groups did not differ significantly in gender distribution, age, marital status, employment, or level of education.

Conditional Goal Setting

Mean CGS scores for participants allocated to MBCT were 90.71 (SD = 20.00) at baseline and 81.57 (SD = 18.79) at follow-up. For those allocated to TAU, the equivalent figures were 105.36 (SD = 16.43) and 103.18 (SD = 28.41). A repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that, by chance, CGS scores were higher at baseline in those allocated to TAU than those allocated to MBCT, F(1, 23) = 5.55, p < 0.05, but that there was no significant main effect of time and no significant interaction. Thus, while change in CGS was in the expected direction, there was no evidence from this small sample that MBCT was able to produce reliable reductions in CGS relative to a treatment as usual condition.

FFMQ

Mean FFMQ score for participants allocated to MBCT was 104.06 (SD = 20.76) at baseline and 113.57 (SD = 20.10) at follow-up. For those allocated to TAU, mean FFMQ score at baseline was 88.75 (SD = 16.32) and at follow-up was 89.72 (SD = 18.16). Repeated-measures ANOVA exploring the effects of MBCT on dispositional mindfulness indicated no significant main effects of time, but a significant main effect of group, F (1, 23) = 7.78, p = 0.01. There was no significant time × group interaction. Follow-up post hoc tests indicated that participants allocated to MBCT showed marginally higher FFMQ scores at baseline, p = 0.06 and significantly higher FFMQ scores at follow-up p = 0.005. However, there was no significant difference between the groups in FFMQ change over the trial period, although mean change was in a positive direction in those allocated to MBCT and negligible in those allocated to TAU.

As a result, we explored whether change over time in dispositional mindfulness was associated with comparable changes in conditional goal setting for the sample as a whole, irrespective of whether or not participants had received MBCT treatment. This analysis does not provide information about the effects of meditation practice on CGS, but as previous findings of an association between dispositional mindfulness and CGS were based on cross-sectional baseline data, analyzing change over time allows for an exploration of whether CGS and dispositional mindfulness change in parallel within a clinical population. Change scores were calculated for both measures. Inspection of the data indicated that both variables were normally distributed. However, two cases were moderate outliers in CGS change, and two were moderate outliers for FFMQ change. In order to preserve data, we computed Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficients to examine associations between change in CGS and change in FFMQ. These indicated a significant correlation across the sample as a whole, rho (25) = −0.45, p < 0.05, suggesting that increases in dispositional mindfulness tended to be associated with decreases in CGS (see Fig. 1). However, this pattern of association was not significantly stronger in those allocated to treatment with MBCT, rho (14) = 0.49, p = 0.076 than those allocated to TAU, rho (11) = 0.34, p = 0.31, and therefore, the overall pattern of associations could not be attributed to the group who had received meditation training.

Summary

While patterns of change for both the CGS and FFMQ measures were in the predicted direction, magnitude of change was relatively small and did not reach statistical significance. Study 1 nevertheless suggests that where dispositional mindfulness does change over time, levels of conditional goal setting will also change in parallel. In clinical studies of treatment interventions, many factors will converge to determine change in cognitive variables over time. With this in mind, study 2 took a different approach and considered the impact of a brief period of meditation on CGS processes in a healthy community sample. While in the traditions from which it originates meditation is usually regarded as an activity practiced over months and years, there is evidence that even short periods of meditation can produce measurable effects on cognitive and affective functioning. For example, Barnhofer et al. (2010) showed that brief periods of breathing meditation and loving-kindness meditation (15 min) produced state changes in affect and resting frontal asymmetry, a measure of approach-withdrawal motivation, assessed by EEG. Similarly, Hutcherson et al. (2008) found increases in positivity towards images of unfamiliar people following a very brief period of loving-kindness meditation, while Zeidan et al. (2010) found changes in performance on several cognitive tasks after only four 20-min sessions of mindfulness of breathing. These results suggest that it is meaningful to consider the impact of brief periods of meditation on cognitive variables such as CGS. This is not least the case because clinical research suggests that most drop out from mindfulness-based interventions occurs very early in treatment (e.g., Crane and Williams 2010), at a point when people may have tried meditation on only a few occasions.

Because it is unclear whether a single period of mindfulness of breathing practice would be sufficient to enable participants to observe their attachment to particular goals, and because loving-kindness meditation might be interpreted by some people to be explicitly about the desire to be happy, and hence might initially increase, rather than decrease, attachment to existing goals, study 2 was exploratory. It considered the immediate effects on CGS of brief periods of either breath-focused or loving-kindness meditation in a community sample with little prior experience of meditation practice and in particular the impact of individual differences in goal-related self-regulation (goal re-engagement—the ability to identify and engage with new rewarding goals when existing goals become unattainable, e.g., Wrosch et al. 2003) on response. Although exploratory, we hypothesized on the basis of previous research, that brief periods of both breathing meditation and loving-kindness meditation would reduce CGS (from pre-meditation levels), but that this effect would be attenuated, or reversed in those low in goal re-engagement.

Study 2

Method

Recruitment

Participants were recruited via posters placed in local community buildings, university buildings, and on local websites, as well as through word of mouth. Volunteers were requested who were aged 18 years of age or over, spoke fluent English, and had little experience of meditation (currently meditating less than once per week). Individuals interested in participating in the experiment were provided with an information sheet about the study. Those who remained interested having read this further information were invited to a testing session. In total, 55 participants attended this session and completed the experimental procedure. A further five were recruited but reported high levels of depression or anxiety during initial screening for eligibility within the experimental session and so were excluded before completing all measures. All participants received a small prize for participating in the study (e.g., confectionary). The study was approved by Oxford University Research Ethics Committee.

Materials and Measures

Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996)

The Beck Depression Inventory is a widely used 21-item self-report instrument for measuring severity of depressive symptoms. The BDI-II has high internal consistency and high 1-week test–retest reliability (Beck et al. 1996). Individuals scoring 20 or more on the BDI-II were excluded.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The Beck Anxiety Inventory is a 21-item questionnaire that measures the severity of symptoms of anxiety. Individuals scoring 19 or more on the BAI were excluded.

FFMQ (Baer et al. 2006)

See description in “Method” of “Study 1”.

MEPGAP—Adapted (Vincent et al. 2004; Hadley and MacLeod 2010)

The Measure to Elicit Positive Future Goals and Plans was utilized as described for study 1. However, in the current study, participants were randomly allocated to one of two conditions. In condition A, they completed ratings of goals 1, 3, and 5 before the meditation or rest period and goals 2, 4, 6 after the mediation or rest period, whereas in condition B, they did the reverse.

Goal Adjustment Questionnaire (Wrosch et al. 2003)

The Goal Adjustment Questionnaire is a 10-item self-report questionnaire, containing two subscales which explore the ability to disengage from unattainable goals (four items), and reengage with new goals when existing goals become unattainable (six items). Goal re-engagement, the ability to find new sources of meaning in life when existing goals are challenged, has the most relevance for conditional goal setting, since it appears to directly contrast with the belief that happiness, self-worth, and fulfillment can only be attained through achievement of particular, existing goals. Items on the re-engagement scale include “If I have to stop pursuing an important goal in my life… I convince myself that I have other meaningful goals to pursue (I seek other meaningful goals/I put effort toward other meaningful goals).” The goal re-engagement scale had excellent internal consistency in the current sample, α = 0.88.

Manipulations

Meditations

The two guided meditations utilized in the study were both approximately 15 min in length and were equated with regard to the amount of time during which the participants were receiving auditory instructions and the amount of time left silent for participants to practice on their own. In the guided breathing meditation, participants were invited to focus their attention on the sensations of their breathing, before broadening their field of awareness to bodily sensations as a whole. They were instructed that if they noticed that their mind had wandered during the meditation, they should notice where their attention had gone and then gently return their attention to the breath or body, without judging themselves.

The loving-kindness meditation began by asking participants to think about a good thing that they had done, or a good quality that they had, or if nothing came to mind to gently focus on their own wish to be happy. After this initial period, they were encouraged to direct feelings of loving-kindness towards themselves by silently repeating four phrases, “may I be safe,” “may I be happy,” “may I be healthy,” and “may I live with ease.” Once they had established loving kindness for themselves, they were asked to use the same phrases to cultivate loving kindness first for someone close, then to someone neutral, then to someone they did not know firsthand, and finally to all people, everywhere. These instructions were based on loving kindness, or metta, meditation as described by Salzberg (2002) and have been used in our previous research (see Barnhofer et al. 2010).

Rest Condition

Participants in the rest condition were instructed that they should find a position that was comfortable and then sit and relax, but try to remain awake. The period of rest lasted 15 min. The experimenter remained quiet and did not disturb the participant during the rest period.

Allocation of Participants to Groups

Participants were randomly allocated to one of six groups defined by allocation to either breathing, loving kindness, or rest and by completion of CGS ratings for goals 1, 3, and 5 preintervention and 2, 4, and 6 postintervention (A/B), or the reverse (B/A). Randomization to groups was conducted through the use of pre-prepared envelopes containing allocations, with an allocation picked at random from the envelope for each consecutive participant. Nineteen participants were randomly allocated to the breathing meditation group (10 females, nine males; nine A/B), 19 to the loving-kindness meditation group (12 females, seven males; 10 A/B), and 17 to the rest group (nine females, eight males; nine A/B). No main effects or interactions were observed when CGS order (A/B or B/A) was entered into the analyses, and so analyses were repeated (and are reported here) without this as a factor.

Procedure

Testing took place individually in a quiet room. At the start of the session, participants were given the information sheet to read and the opportunity to ask any questions. Written informed consent was then obtained. Participants began by filling in a series of questionnaires which gathered information on basic demographic characteristics, mood state (the BDI and BAI), and prior experience of meditation. Following review of this information, those participants who remained eligible (little experience of meditation, BDI and BAI < 20) completed the MEPGAP interview and made conditional goal setting ratings for three of their six most important goals. The procedures for the meditation or rest period were explained. The experimenter remained unobtrusive during the period of meditation or rest that followed to prevent distraction. After the meditation, the participant completed the second set of CGS ratings. Following the completion of these, they were fully debriefed and thanked for their time.

Data Analysis

Inspection of key variables indicated that CGS scores did not contain any outlying values. The pre-meditation/rest CGS score departed moderately from normality, while the post-meditation/rest CGS score was normally distributed. Since transformation of the pre-CGS score did not significantly improve the distribution, the untransformed data were retained.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants ranged in age from 20 to 63 years, with a mean of 27 years (SD = 9.62). The majority of the participants were white (76%); 11% were Asian, 7% were of mixed ethnicity, 2% were black, 2% were Hispanic, and 2% did not identify with any of the previous categories. Twenty-nine percent of the sample had completed only compulsory schooling, 62% had obtained an undergraduate degree, and 9% had obtained a postgraduate degree. Regarding marital status, 55% of the participants were single, 29% were in a relationship, 9% were married or cohabiting, and 7% were either separated, divorced, or widowed.

BDI-II and BAI Scores

The mean BAI score for the sample as a whole was 3.96 (SD = 3.13, range 0–13), out of a maximum total of 63, and the mean BDI score was 4.92 (SD = 4.15, range 0–14), also out of a maximum total of 63. Thus, the sample had low mean levels of depression and anxiety.

Conditional Goal Setting, Goal Re-engagement, and FFMQ

The mean total CGS score, across items measuring happiness, self-worth, and fulfillment for those goals rated before the meditation or rest period was 28.05 (SD = 11.77). This corresponds to a score of 3.06 (SD = 3.12) on each 1 to 8 scale, indicating that happiness, self-worth, and fulfillment were not regarded as highly contingent on successful attainment of important goals in this sample. In order to explore whether there was a significant association between CGS and dispositional mindfulness in this healthy community sample, baseline CGS scores were correlated with total FFMQ score. This revealed a significant negative correlation, r = −0.36, p = 0.007 (Spearman’s rho = −0.35, p = 0.008), suggesting that the previously found association between low dispositional mindfulness and high conditional goal setting is not confined to clinical groups (see Fig. 2).

The mean goal re-engagement score was 23.23 (SD = 3.96). Pearson’s correlation coefficients indicated that goal re-engagement was significantly correlated with total FFMQ score, r = 0.37, p = 0.005. Thus, people who had higher levels of dispositional mindfulness are more able to identify new rewarding goals when existing goals become unattainable. However, baseline levels of conditional goal setting and goal re-engagement were not significantly correlated with one another, r = −0.22, p = 0.11.

Effects of Meditation on Ratings of Conditional Goal Setting

In order to explore the effects of brief periods of meditation on ratings of CGS, we conducted a two (time: pre and post) by three (meditation type: breathing, loving kindness, and rest) repeated-measures ANOVA with CGS rating as the dependent variable. This revealed a main effect of time, F (1, 52) = 6.58, p = 0.013, but no significant main effect of group and no significant time × group interaction. Comparison of the means across the sample as a whole indicated that, contrary to expectation, levels of CGS increased slightly from pre- (M = 28.05, SD = 11.77) to post-meditation (M = 32.15, SD = 13.81) or rest across the sample as a whole.

In order to explore whether goal adjustment ability influenced reactions to meditation, we conducted a repeated-measures ANOVA, entering goal re-engagement ability as a second between-subjects factor. Participants were divided into three equal groups according to whether they reported low (eight breathing, six LK, and six rest), moderate (five breathing, eight LK, and four rest), or high (six breathing, five LK, and seven rest) levels of goal re-engagement. Changes in CGS were analyzed in a two (time: pre and post) by three (group: breathing, loving kindness, and rest) by three (re-engagement: low, moderate, and high) mixed ANOVA. As before, this revealed a main effect of time, F (1, 46) = 12.46, p = 0.001. There was also a significant two-way time × re-engagement interaction, F (2, 46) = 2.49, p = 0.02, qualified by a significant three-way time × re-engagement × group interaction F (4, 46) = 5.55, p = 0.001.

The three-way interaction was broken down into separate time × group ANOVAs for participants low, moderate, and high in goal re-engagement ability. The ANOVA for participants low in goal re-engagement ability revealed a significant main effect of time, F (1, 17) = 37.85, p < 0.001, and a significant time × group interaction, F (2, 17) = 16.50, p < 0.001. Post hoc tests indicated a significant increase in CGS ratings from pre- to post-meditation in participants allocated to the loving-kindness meditation condition (pre: M = 26.67, SD = 9.48; post: M = 49.50, SD = 7.87; p < 0.001), but no significant change in those allocated to breathing (pre: M = 31.25, SD = 12.98; post: M = 34.75, SD = 13.23, p = 0.18) or rest M = 33.67, SD = 13.23; post: M = 36.50, SD = 15.04, p = 0.34). In those low in goal re-engagement ability, allocated to loving-kindness meditation CGS scores increased from an average rating of approximately 3, to a rating of 5.5 on an eight-point scale. As shown in Fig. 3, this increase appeared to be highly consistent across the participants. In contrast, the ANOVAs for participants moderate or high in goal re-engagement ability indicated no significant main effects or interactions.

Discussion

The two studies presented in this paper explored the association between mindfulness and conditional goal setting and the impact of meditation training on these variables. Study 1 examined changes in dispositional mindfulness and conditional goal setting in a sample randomized to either immediate or delayed treatment with MBCT. Although there was no evidence of significant differential change in the two groups, patterns of change in mindfulness and CGS favored those allocated to MBCT, and across the sample as a whole increases in dispositional mindfulness over the 3–4-month period were associated with significant decreases in CGS. Study 2 confirmed the cross-sectional association between dispositional mindfulness and CGS in a sample with low levels of depression and anxiety. These findings together support the suggestion that a high level of dispositional mindfulness is associated with low conditional goal setting, and that where dispositional mindfulness changes significantly, levels of CGS are likely to also shift in parallel.

The results of study 2 indicated that participants who reported low goal re-engagement responded to a (brief and unfamiliar) loving-kindness meditation with marked increases in conditional goal setting, while those moderate or high in goal re-engagement, and those allocated to rest or breathing meditation, showed no significant change. The finding that people low in goal re-engagement ability responded negatively on initial exposure to loving-kindness meditation is consistent with the findings of previous research. It is recognized that people differ in their initial reactions to the practice (e.g., Salzberg 2002; Johnson et al. 2009; Barnhofer et al. 2010) and that it may take time for benefits to accrue. For example, Fredrickson et al. (2008) found that differences between controls and individuals practicing loving-kindness meditation on a daily basis only began to emerge after 2 weeks. In loving-kindness practice, participants are asked to direct feelings of loving kindness towards themselves and others through the silent repetition of phrases such as “may I be happy” and “may I live with ease.” For people who find it difficult to identify new meaningful goals, initial exposure to loving-kindness meditation may only serve to increase the desire to be happy and hence the salience and importance of existing goals, without generating sufficient unconditional positive affect to enable alternative paths to fulfillment to become apparent. As such, for individuals low in goal re-engagement (those who are known to find it difficult to engage with new rewarding goals when existing goals are challenged), it may be necessary to introduce loving-kindness meditation following greater preparation in order to reduce the likelihood of negative reactions, and indeed, greater experience with loving-kindness meditation may be required by most individuals before beneficial effects on psychological functioning emerge.

The absence of an effect of a brief period of breathing meditation on conditional goal setting may relate to a number of issues, but most importantly, the fact that participants completed only a 15-min meditation session in the lab. Although previous studies using similarly brief mode of processing manipulations, regarded by some as providing an analog of meditation, have demonstrated effects on cognitive variables (e.g., Watkins and Teasdale 2001, 2004), it is likely that 15-min is simply insufficient to bring about changes of the magnitude that would be required in order to alter ratings of conditional goal setting. In order to be able to observe and reflect on one’s own attachment to particular goals or outcomes, more extended practice over weeks or indeed months may be required. However, the fact that individuals low in goal re-engagement did not respond negatively to breathing meditation does suggest that it is the nature and content of loving-kindness practice, rather than meditation per se, which produced the negative impact of loving kindness on CGS, and in this regard, retaining a comparison of two distinct forms of meditation practice, albeit over a greater number of practice sessions, may be helpful in a future study.

A number of limitations of the current studies must be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample size employed in study 1, for comparisons between immediate and delayed treatment with MBCT, was small, and hence the study lacked power. Equally, although the overall sample size was adequate in study 2, groups defined on the basis of a goal re-engagement were again more restricted, and so the results, while they do not appear to be the result of outliers, should be interpreted cautiously. Second, in study 2, we employed a healthy sample whose levels of CGS were relatively low. This may have led to floor effects with little room for further reductions in CGS following meditation, and it would be interesting to explore the impact of both types of meditation on CGS in a sample likely to display stronger CGS tendencies at the outset. Finally, we did not explore whether the effects of meditation in study 2 were mediated by changes in state mindfulness, since the capacity to measure such changes is hampered by lack of a good measure, and indeed by consensus as to precisely what such a measure might assess.

Despite these limitations, the findings of the studies reported here are still of interest. They provide support for the proposed link between dispositional mindfulness and conditional goal setting, including evidence of both a cross-sectional association in a non-clinical sample and consistent patterns of change in the two variables in a clinical sample over a period of 3–4 months. Additionally, they add to existing evidence that initial exposure to meditation practice may have counterintuitive effects. This is important because our clinical trials have found that, when participants drop out from mindfulness-based interventions, they to do so early in treatment, after relatively little exposure to the practice of mindfulness. As meditation-based interventions becoming increasingly widespread, understanding the impact of individual differences on both initial and longer-term responses to meditation is likely to be of critical importance in improving the acceptability and effectiveness of treatment. Future research is now required to examine the relationship between initial reactions to meditation and longer-term response, as well as to clarify which forms of meditation practice are most accessible for individuals with particular cognitive profiles.

References

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lynkins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342.

Barnhofer, T., Crane, C., Hargus, E., Amarasinghe, M., Wider, R., & Williams, J. M. G. (2009). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as a treatment for chronic depression: A preliminary study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 366–373.

Barnhofer, T., Chittka, T., Nightingale, H., Visser, C., & Crane, C. (2010). State effects of two forms of meditation on prefrontal EEG asymmetry in previously depressed individuals. Mindfulness, 1, 21–27.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the BDI-II. San Antonio: Psychological.

Brothers, S. C., & Maddux, J. E. (2003). The goal of biological parenthood and emotional distress from infertility: Linking parenthood to happiness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 248–262.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1998). On the self-regulation of behaviour. New York: Cambridge University.

Crane, C., & Williams, J. M. G. (2010). Factors associated with attrition from mindfulness based cognitive therapy for suicidal depression. Mindfulness, 1, 10–20.

Crane, C., Barnhofer, T., Duggan, D. S., Hepburn, S. R., Fennell, M. J. V., & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and self-discrepancy in recovered depressed patients with a history of suicidality. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 775–787.

Crane, C., Barnhofer, T., Hargus, E., Winder, R., & Amarasinghe, M. (2010). The relationship between mindfulness and conditional goal setting in depressed patients. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42, 281–290. doi:10.1348/014466509X455209.

Crocker, J., Brook, A. T., Niiya, Y., & Villacorta, M. (2006). The pursuit of self-esteem: Contingencies of self-worth and self-regulation. Journal of Personality, 74, 1749–1771.

Diodonna, F. (Ed.). (2009). Clinical handbook of mindfulness. New York: Springer.

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1045–1062.

Hadley, S. A., & MacLeod, A. K. (2010). Conditional goal setting, personal goals and hopelessness about the future. Cognition and Emotion. doi:10.1080/02699930903122521.

Hayes, A., Hope, D. A., & Hayes, S. (2007). Towards an understanding of the process and mechanisms of change in cognitive behavioral therapy: Linking innovative methodology with fundamental questions. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 679–681.

Hayes, A. M., Laurenceau, J. P., Feldman, G., Strauss, J. L., & Cardaciotto, L. (2007). Change is not always linear: The study of nonlinear and discontinuous patterns of change in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 715–723.

Hoffman, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect on mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 169–183.

Hutcherson, C. A., Seppala, E. M., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Loving kindness meditation builds social connectedness. Emotion, 8, 720–724.

Johnson, D. P., Penn, D. L., Fredrickson, B. L., Meyer, P. S., Kring, A. M., & Brantley, M. (2009). Loving kindness meditation to enhance recovery from negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 499–509.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living. Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York: Dell.

Martin, L., & Tesser, A. (1989). Toward a motivational and structural theory of ruminative thought. In J. S. Uleman & J. S. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thought (pp. 306–326). New York: Guilford.

McIntosh, W. D. (1997). East meets west: Parallels between Zen Buddhism and social psychology. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 7, 37–52.

McIntosh, W. D., Harlow, T. F., & Martin, L. L. (1995). Linkers and non-linkers: Goal beliefs as a moderator of the effects of everyday hassles on rumination, depression and physical complaints. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 1231–1244.

McIntosh, E., Gillanders, D., & Rodgers, S. (2009). Rumination, goal linking, daily hassles and life events in major depression. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 17, 33–43.

Salzberg, S. (2002). Loving-kindness. The revolutionary art of happiness. Boston: Shambhala.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: The Guilford.

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 373–386.

Street, H. (2001). Exploring the role of conditional goal setting in the etiology and maintenance of depression. Clinical Psychologist, 6, 16–23.

Street, H. (2003). The psychosocial impact of cancer: Exploring relationships between conditional goal setting and depression. Psycho-Oncology, 12, 580–589.

Street, H., Nathan, P., Durkin, K., Morling, J., Dzahari, M. A., Carson, J., et al. (2003). Understanding the relationship between wellbeing, goal-setting and depression in children. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 155–161.

Vincent, P. J., Boddana, P., & MacLeod, A. K. (2004). Positive life goals and plans in parasuicide. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 11, 90–99.

Watkins, E., & Teasdale, J. D. (2001). Rumination and overgeneral memory in depression: effects of self-focus and analytical thinking. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 353–357.

Watkins, E., & Teasdale, J. D. (2004). Adaptive and maladaptive self-focus in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82, 1–8.

Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., Miller, G. E., Schulz, R., & Carver, C. S. (2003). Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: goal disengagement, goal re-engagement and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1494–1508.

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19, 597–605.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rosie Winder, Myanthi Amarasinghe, and Emily Hargus for their assistance with the data collection for study 1, as well as all our participants for giving their time to take part in the research.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0031-4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Crane, C., Jandric, D., Barnhofer, T. et al. Dispositional Mindfulness, Meditation, and Conditional Goal Setting. Mindfulness 1, 204–214 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0029-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0029-y