Abstract

The lime industry is a highly energy intensive industry, with a huge presence worldwide. To reduce both production costs and pollutants emissions, some lime production plants are introducing more environmentally-friendly energy sources, such as local agro-industry residues. In this paper, a numerical tool is presented, which simulates a large-scale Parallel Flow Regenerative (PFR) kiln that currently uses coke as main fuel. The developed tool aims at investigating the combustion process under conditions of co-firing of coke and biomass and to assist the plant operators in the optimization of such operating conditions. To achieve this goal, a two-way coupling Euler–Lagrange approach is used to model the dynamics of the particulate phase and their interaction with the gas phase. Pyrolysis, volatiles oxidation and char oxidation are modelled by kinetics/diffusion-limited model (for heterogeneous reactions) and mixture fraction approach (for homogeneous reactions). Moreover, two methods are investigated for representing the limestone bed: a porous medium (PM) approach and a “solid blocks” (BM) tridimensional mesh. Comparison of the results for the case of 100% coke showed that the ideal “blocks” method is more accurate as it adequately simulates the scattering of fuel particles through the PFR kiln anchor, which is limited with the PM approach. Moreover, the temperature profile, maximum and minimum temperatures, as well as CO2 and O2 concentrations at outlet, are comprised in the expected range for this technology, according to available literature. Finally, the predicted results of a co-firing case with 60% biomass (in mass) were validated with measurements in an industrial facility, with production capacity of 440 calcium oxide tons per day. The results suggest that the model is fairly accurate to predict gas temperature, as well as O2 and NOX concentrations at the kiln outlet. Although some improvements are recommended to refine the CFD predictions, these promising results and the high computational efficiency laid the foundation for future modelling of co-firing of coke and biomass, as well as the modelling of the lime calcination process. It also paves the way for facilitating the reduction of pollutant emissions thus contributing to a more sustainable lime production.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Statement of Novelty

This paper presents a novel method that modelled the combustion of coke and biomass in a parallel flow regenerative (PFR) lime kiln. For that purpose, an equivalent (in terms of heat transfer and pressure drop) representation of the limestone bed is developed and coupled with comprehensive CFD co-firing models. Moreover, the predicted data are compared to measurements in a full-scale industrial facility. Current literature on PFR kilns is very scarce and, to the best of the author’s knowledge, simulation analysis of co-firing in PFR kilns has not been reported earlier.

Introduction

Globally, lime is the main source of calcium worldwide, thanks to its relatively low cost and its geographical distribution. Also, it is the largest-selling alkali and the fifth most produced chemical with multiple applications in sectors such as iron and steel, flue gas, water and sludge treatments, civil and construction engineering, agriculture, soil protection, food and feed additives and pharmaceuticals [1]. In 2006, total world lime production achieved 313 Mt, being EU production the 8.6% with more than 100 companies [2]. Lime is produced by the calcination of limestone (mainly formed by calcium carbonate CaCO3) to produce calcium oxide (CaO), releasing CO2 [3]. This endothermic reaction takes place at a temperature between 900 °C and 1200 °C, hence is a highly intensive energy process, where fuel accounts between 30 and 60% of production costs [4] and 30% of GHG emissions [5]. The potential reduction of CO2 emissions by substituting current fossil fuel by carbon–neutral fuels can reach a 20% in a state-of-the-art lime plant and up to 40% if it is integrated into a conventional cement plant [6]. In that sense, the reduction of GHG emissions due to combustion processes in the industrial sector is a crucial topic in the European Roadmap in order to achieve the goal of a reduction of 83% to 87% in 2050 [7]. Moreover, the best approach to improve the kiln efficiency is to enhance the control of its operational parameters, specifically ratio limestone/fuel supply, combustion air excess, size distribution of the limestone rocks, and temperature of the bed [8].

Three main types of modern kilns are used for the calcination of lime. The main product of shaft kilns (also called High Performance Shaft—HPS kilns) is the low-reactive quicklime (diameter of raw stone from 20 to 175 mm), which presents multiple applications. The Parallel Flow Regenerative (PFR) kilns are devoted to the production of high-reactive, soft-burnt quicklime (stone diameter from 90 to 125 mm), mainly used in the steel industry. Finally, the rotary kilns are used to produce dolomitic lime and higher purity quicklime (stone diameter from 15 to 40 mm) [9]. Two other technologies have been extensively used during the last decades, but recently overcame. On the one hand, the Annular Shaft Kilns (ASK) are used in the production of high-reactive quicklime, but its energy consumption and capital expenditure (CAPEX) are higher than PFR. On the other hand, for the soda ash and sugar industry, where a moderate-reactive lime and high concentration of CO2 are necessary, only mixed-feed single shaft kilns can be used. This technology, which uses coke as fuel, is also extensively used for quicklime calcination in developing economies [10]. Despite the fact that, in 2006, there were a total of 597 kilns producing commercial lime in EU-27, of which 551 (about 90%) were shaft kilns [4], the literature devoted to the modelling of combustion process in lime kilns is very limited. This can be mainly explained due to the difficulties of modelling gas–solid reactors, such as PFR lime kilns, which involve a number of physical, chemical and thermal phenomena that are dependent from each other and thus require an iterative procedure. Those phenomena include flow motion of the solid and gas phases, heat transfer by conduction, convection and radiation and, finally, mass transfer by the homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions. In addition, the numerical discretization of full-scale industrial kilns involves very large mesh, with hundred thousands of computing cells, due to the large dimensions of such reactors. Accordingly, simplifications are needed in the modelling schemes in order to allow computing in a reasonable time.

Most of the literature is focused on shaft kilns and most of the cases present analytical models. The common approach of the analytical (semi-empirical) models is to consider the bed of stones as a porous medium. The modelling is focused on the calcination processes, by uncoupling the transport equations inside the limestone bed from the gas composition and gas and wall temperatures. It is worth underlining that the limestone calcination process used to be mathematically modelled in one dimension (i.e., the furnace height [11]) and it is controlled by heat transfer mechanism (not by kinetics) [12]. This approach has been found on single shaft using natural gas [13, 14] or heavy oil as fuel [15], ASK with natural gas as fuel [16, 17], and mixed-feed shaft kilns with coke [18, 19].

In [20], the analytical modelling of both HPS and PFR furnaces is extensively presented, using natural gas and lignite as fuels. This work compares both technologies and the impact of the fuel at commercial scale, and it demonstrates the challenges associated with the validation in this kind of kiln. The model has been validated only by pressure drop and wall heat losses measurements. On the other hand, a detailed analytical model for rotary kilns is presented in [21], with specific focus on heat transfer and scaling up, and an extensive validation process at laboratory scale.

Validation challenges have been also observed in the most advanced Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD from now onwards) models of PFR kilns [22]. This work presents a CFD-DEM coupled model [23] for a full scale PFR kiln, on different operation stages using natural gas as fuel. Despite the high quality of the model and its high computational cost, this model has been only validated under commissioning phase with two temperature probes.

On the other side, the application of CFD methods to combustion process in diverse technologies at industrial scale are plentiful and there exist numerous references in the available literature, e.g. [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Specifically, the pulverized coal combustion was investigated through different approaches (e.g., generalized finite rate model and mixture fraction /PDF approach) so as to compare them and select the most appropriate for the large-scale rotary lime kiln case. In reference [36], a three-dimensional CFD simulation is performed using similar methods to those exposed in the present paper, but in a rotary kiln. Particularly, the calcination of limestone bed and its effects were simplified.

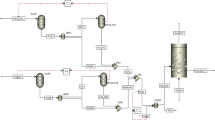

The present study develops a CFD model that aims to calculate the flow of gas and fuel particles, temperatures and pressure drop inside the kiln during the combustion of pulverized solid fuel. The main goal is to simulate the combustion process that occurs in the PFR shaft kiln located near Zaragoza (Spain) and to be the basis for improvement of operating conditions when co-firing is performed. The PFR kiln object of this study is schematized in Fig. 1. It is worth to note that the CFD model needs to balance accuracy, to capture the main characteristics of combustion in the shaft kiln, and computational cost. This requirement stems from usability for practical purposes: it takes almost three days to observe a change of behavior in the kiln or a shift in the quality of the lime product after a modification of the operation conditions. Once such a model is available, it can be used to predict the behavior of the kiln upon changes in the mode of operation. Thus, the plant operators may evaluate the impact of modifying the fuel on the pollutant emissions, the aerodynamics and the temperature profile before attempting such modification in the actual kiln. This will not only save time and money, but also prevent performing tests with a negative result in the actual facility.

Adapted from [37]

PFR shaft kiln analyzed in the present study

To reach this main objective, the present work develops a novel method to model the co-firing process of coke and biomass in an industrial PFR lime kiln with a focus on the coupling between combustion process and the non-reactive physical behavior of the limestone bed. The main novelty is the development of a computationally efficient CFD model of a full scale PFR lime kiln applied to biomass/coke co-firing. The current literature on PFR kilns is very scarce, and the few CFD models are focused on very detailed (and computationally expensive) simulations of the limestone bed using natural gas as fuel. The model presented in this paper has been extensively validated with real plant data and due to the relatively low computation cost could be subsequently used for control and optimization issues in the industrial environment.

Case Study

Natural limestone is crushed to stones of several centimeters and subject to a process of calcination at high temperatures that produces calcium oxide (lime) and carbon dioxide [38]. This process used to be carried out in shaft kilns [10], where high temperatures are produced by burning fuel within a continuously moving bulk of stones. The so called “soft-burnt lime” is a highly reactive product obtained at temperatures around 900 °C (1173 K) [39]. Higher temperatures set a process of recrystallization that should be avoided, since it negatively affects the reactivity of the lime.

The kiln to be analyzed is a PFR shaft kiln, which operates in cycles as follows: the burner lances in shaft 1 transport the fuel along with the primary combustion air, while the lances of the shaft 2 expel only primary combustion air. The shaft 1 is called the burning shaft, while the shaft 2 is the regenerative shaft (see Fig. 1). The operation is schematically depicted in Fig. 2. Limestone enters via the upper part of both shafts. The burner lances at the top of the burning shaft inject fuel and primary combustion air, thus setting ignition. Moreover, secondary combustion air enters uniformly through the upper part of the burning shaft, while refrigerating air (also called “lime cooling air”) comes uniformly from the bottom of both shafts. Note that this operation mode also pre-heats the combustion air.

Left: frontal view showing the air and fuel inlets, as well as limestone and gas circulation. Right: frontal (up) and lateral (down) views that will be used to report the results of the CFD simulations (see Sect. 4). The profiles of wall temperature is presented in the left (calcination zone 1173 K—inlet/outlet 300 K)

After a cycle of several minutes, the shafts reverse their roles, i.e., the shaft 2 becomes the burning shaft (where fuel, and primary and secondary combustion airs are injected), and the shaft 1 becomes the regenerating shaft, where only primary air is introduced and where gases are exhausted. The kiln continuously operates in this alternating mode. Limestone is calcined in the burning shaft in parallel flow (fuel and stones flow in the same direction), while the limestone in the regenerative shaft is pre-heated in counter flow by the hot gases that cross the channel near the base. Further details are given below when addressing the computational model.

In the present study, the kiln uses pulverized solid fuels for the combustion process. Although several types of solid fuels have been tested at the facility, up to date the main fuel that is used consists in coke, i.e., a fossil fuel composed mostly of carbon (88% in mass), with low content of ashes and volatile matter. The coke is imported from North America and, due to its high purchase cost and the environmental impacts associated to its use, the facility aims at partly replacing it by a local and more environmentally-friendly solid fuel, i.e., solid biomass. This type of fuel differs substantially from fossil fuels in their larger content of volatiles and lower calorific value. On the other hand, the biomass fuels generally present the advantage of producing lime with a lower sulfur content, thus increasing its quality and its market price. The use of biomass also positively impacts on the de-carbonization of the process by reducing greenhouse gas and pollutant emissions, especially nitrogen oxides (NOX) and sulfur oxides (SOX). On the contrary, the milling of biomass usually consumes more energy compared to mineral fuels, hence particle size uses to be higher in the case of solid biomass in order to maintain the fuel pretreatment costs [40]. The plant uses two different mills, one for each type of fuel. After the mills, the pulverized fuels are stored separately in intermediate storages before being mixed and fed into the kiln. In the present work, the solid biomass that is used to develop and validate the present CFD simulations consists in grape seeds flour, which proceeds from local agro-industries. The proximate and ultimate analyses, as well as heating value, of the biomass and the coke considered in this study are shown in Table 1. Moreover, Table 2 presents the pulverized fuel spherical particle diameter, following Rosin–Rammler distributions.

Computational Model

Physical Models

The calculations necessary to understand and to assess the interaction between gas flow and combustion inside the kiln were carried out using the commercial software FLUENT (v17.2). The main well-known model governing equations are presented in Appendix 1 and more detail may be found in [41]. The dynamics of the gas inside the kiln are modeled by the steady-state Reynolds averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations. Turbulence closure is included via the standard k-ε model with standard wall functions. This formulation is an appropriate compromise in industrial applications between a realistic representation of turbulent flow and a fast calculation. Moreover, previous studies underlined a good agreement between this formulation and experimental results in very different multiphase reactors such as a shaft kiln modelled by a system of packed spheres [42], or a rotary kiln [43]. Wall functions are based on empirical equations and allow an accurate representation of the turbulence without solving the viscosity-affected region close to the walls (with a substantial increase of computational resources).

The dynamics of the particulate phase (both coke and biomass) and their coupling with the gas phase is modeled using a two-way coupling Euler–Lagrange approach. This approach takes into account the composition of the particles (mass fractions of ash, volatiles and fixed carbon), their particle size distribution, as well as the processes of devolatilization and char oxidation. Due to the micrometric size of the particles, they are dragged by the flow without dynamically affecting it. However, there is a bi-directional exchange of momentum, energy and mass between the fuel particles and the gas flow. The number of particles is determined from the mass flow rate of fuel, as well as the density and size distribution of the particles. In the case of co-firing, two combusting particles are defined, one for coke and another for the corresponding biomass. Each one has its own composition and kinetic properties as detailed below. Since the biomass is mixed with the coke prior to injection in the furnace, two injections for each lance in the burning shaft are defined, one for each type of fuel.

The radiative heat transfer is computed using the P1 model. Although this simple model is known to present some deviations at very high and low temperatures, it was chosen for its simplicity and because of our moderate temperature of interest. i.e., around 900 °C in the whole simulation volume. By other side, the P1 model takes into account the radiative exchanges between the gas and the particles (as well as the wall and bed surfaces) and it has shown to be accurate in the simulation of both pulverized coal and biomass combustion [44,45,46]. The absorption coefficient of the gas is modeled through the weighted-sum-of-grey-gases (WSGG) approach. Scattering of particles is assumed to be isotropic since the particles are small enough to be considered almost spherical and because the particle rotation is included in the treatment. These two factors tend to average-out anisotropies in the scattering due to particles. On the other hand, the gas is considered incompressible since maximum velocities are of the order of tens of meters per second (Ma < 0.3). Therefore, the actual density of the gas is determined according to the ideal gas model. Finally, the heat transfer mechanism in the particles is computed by a simple heat balance to relate the uniform temperature of the particle to the convective heat transfer (using the using the Ranz and Marshall’s correlation) and the absorption/emission of radiation at the particle surface from P-1 model.

Co-firing Model

The combustion of fuel particles involves three main processes: devolatilization, oxidation of volatile products and char oxidation. Devolatilization consists in the release of volatile products, such as tar and low molecular weight gases, from the fuel particles. In the case of oxygen-rich fuels, such as biomass, large quantities of CO and CO2 can be formed. Subsequently, volatiles are oxidized in the presence of combustion air supplied to the system. The main contents of the gas are CO, CO2, H2O, H2, CH4 and other hydrocarbons. The char core left by the devolatilization mostly consists of C, N, and O and it is slowly oxidized in the presence of the oxygen contained in the air.

The devolatilization of both coal and biomass particles is modeled assuming that all devolatilization process occurs in one step according to the reaction [47]:

where \(X\) is the volatile fraction, and \({k}_{a}\) is the rate constant. Kinetics is defined by a first order single step Arrhenius model:

where \({X}^{*}\) is the amount of volatiles released at complete pyrolysis, \(R\) is the gas constant (J kmol−1) and \(T\) is the absolute temperature (K).

The frequency factor (\({A}_{a}\)) and activation energy (\({E}_{a}\)) for the kinetic rate were obtained from literature and presented in Table 3. Coke devolatilization was assimilated to anthracite [41]. Grape seed devolatilization kinetics were obtained by means of Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis (TGA) experiments under similar combustion conditions [48].

The char combustion model applied was the kinetics/diffusion-limited based on the models of Baum and Street [49] and Field [50], assuming a first order C–O2 reaction mechanism. The Burnout Stoichiometric Ratio was fixed to 1.33, assuming that C (s) is oxidized to CO [28, 51,52,53,54]. The combustion rate is defined as the variation of mass of char particle \({(m}_{p})\) according to:

where \({A}_{p}\) is the surface area of the particle, \({P}_{ox}\) is the partial pressure of oxygen, \({D}_{0}\) is diffusion rate coefficient and \({R}_{c}\) is the kinetic rate of combustion of char [41]:

The value of the mass diffusion limited rate constant (\({C}_{1}\)) was set to 5·10–12 [55]. The values of the kinetic parameters (Table 3) were determined from the composition of the fuel according to Hurt and Mitchell correlation [56].

The combustion of the gases is modeled using the mixed-is-reacted model. This approximation is valid for reacting flows with high Damköhler numbers (Da ≫ 1). In this model, thermochemistry is reduced to a single parameter, the so-called mixture fraction [28], which is defined as the mass fraction of burned and unburned fuel. This approach has the advantage of introducing only one more transport equation to the scheme. Mass fractions of fuel, oxidant and products are simulated by solving the mean and variance of the mixture fraction transport equation for each fuel, with a specific probability density function (PDF) for each solid fuel (coke and biomass).

With respect to the emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOX), their formation is estimated as a post-process. There are three main sources of NOX during combustion: thermal NOX, prompt NOX and fuel NOX. Thermal NOX are formed through the oxidation at high temperatures of the nitrogen that comes within the combustion air. By other side, prompt NOX are formed by the oxidation of the fuel nitrogen in the presence of radicals such as C, CH and CH2. Finally, the dominant source of NOX emissions during the solid fuels combustion is the so-called “fuel NOX”, which arises from the oxidation of the nitrogen contained in both the volatiles and the char residue. To conclude, Table 4 summarizes the values used to set up the NOX model in the present calculations. The values used for the biomass predictions were taken from available literature for similar fuels [57, 58]. As expected, the NOX modelling routes for biomass and coke are different due to the nature of the fuels. Biomass contains more nitrogen, but the conversion routes to NOX favor the formation of NH3 instead of HCN. Since the latter is a precursor of NOX, using biomass fuels usually results in a reduction of NOX emissions.

Limestone Calcination Model

Due to the process of comminution, limestone particles present an average size of 4 cm, which, for simulation purposes, would require the representation of tens of thousands solids to fill in the actual volume of the kiln. In the literature, there are studies that tackle this problem by simulating only a section of the kiln and by employing a hybrid DEM-CFD technique, e.g. in [23, 59]. A CFD simulation models the flow of gas through a porous medium, while limestone movement is computed by means of a discrete element method (DEM) simulation running in parallel. In this approach, the gas flow is unaffected by the dynamics of the stones, while it provides the temperature distribution according to which the calcination process is computed. The DEM simulation allows to compute the conversion degree of the limestone as it moves downwards through the kiln. This hybrid approach is very accurate as regards to mechanical movement and conversion reactions of the solids (limestone), but the fuel combustion is either approximated by a volumetric heat source term [59] or it is calculated by a standard “one-step methane/air combustion” using an Arrhenius rate expression [23]. Moreover, despite the relatively low number of cells (120,000 computing cells for CFD simulation in [23]), the CFD-DEM coupling method is complex and, above all, highly time-consuming, which make its use for industrial scale simulations problematic. DEM simulations are more computationally expensive than CFD [60], especially for the large amount of stones involved in this case. In addition to the two different types of simulations, it is necessary to implement a communication system to translate data between them. As a result, a simulation involving a section of a similar kiln (not the whole volume) can last up to three weeks [22].

Taking into consideration that the present study is focused on the understanding and improvement of the combustion process under co-firing conditions and that it consists in an industry-oriented approach, the authors built up two different models to account for the limestone. Then, the results of each model are compared and the most appropriate representation of limestone is selected for running the complete set of simulations. In the first method, a porous medium approach is used to model the lime contained within the volume of the kiln. This method is very convenient because it allows generating a high-quality mesh (see Fig. 3), composed of 3.5 × 106 cells. Most of them are hexahedral (mean cell size 56 mm), except around the lances and the crossover channel, where tetrahedral cells are used (only 12 cells present an aspect ratio below 0.2).

The porous medium is modeled by setting an appropriate value of the porosity, as well as its permeability and inertial loss coefficient, which can be determined from the known size distribution of stones in the kiln. Values are shown in Table 5. The porosity obtained was 0.36, which is in agreement with values reviewed from literature, e.g. [23]. The porous medium approach applies the Darcy law to compute the gradient of pressure imposed upon the flowing gas along the porous zone, and the corresponding velocity field.

The second method for limestone representation considers the presence of stones as a series of solid bricks scattered inside the kiln. In this model, the bricks are sized such that the free volume they leave matches the estimated porosity as calculated earlier (0.36). Mesh generation is more difficult in this case and a grid-independence study is carried out in order to find out the most suitable cell size (see Appendix 2). This idealized geometry obtained by this method, as well as the mesh generated, are depicted in Fig. 4, where the mean cell size of structured hexahedral cells varies from 8 × 8 × 50 to 25 × 25 × 50 mm, with a minimum of 6 cells between bricks.

Boundary Conditions and Model Implementation

The process of calcination is not modeled in the present simulations, as the main objective of this study is to evaluate the impact of biomass co-firing on the combustion parameters inside the kiln. For the porous medium approach (method 1), the appropriateness of the conditions for the calcination process is assessed by monitoring the gas temperature; i.e. the appropriate value is expected to be around 900 °C, as suggested by previous review [4]. In the approach using solid bricks (method 2), the brick walls constitute a boundary condition, where the wall temperature is coupled to the temperature of the surrounding fluid by convective heat transfer. In this way, the temperature of each brick is dynamically calculated, instead of being fixed.

Given that calcination is not modelled, the large amount of carbon dioxide liberated during the calcination process has to be taken into account during the simulations. This is important not only for the correct calculation of gas species concentrations, but also for the calculation of the radiative heat transfer since carbon dioxide is a participative gas [61]. The presence of carbon dioxide has been considered by introducing this gas component through air inlets. To estimate the carbon dioxide concentration at inlets, actual data from lime production is used (CO2 mole fraction = 0.33). The suitability of this solution has been ascertained by checking the oxygen concentration at the exit of the kiln. This model with carbon dioxide in air inlets produced an oxygen concentration in good agreement with measurements in the kiln.

As regards the temperature boundary conditions for the kiln walls, a temperature of 900 °C (1173 K) is fixed on kiln walls at the calcination zone and the ambient temperature is fixed at bottom and top inlets (see Fig. 2).

Finally, the RANS equations are solved using the SIMPLE scheme for the pressure–velocity coupling and PRESTO for pressure interpolation. The under-relaxation values are reduced with respect to their default values. This scheme allows obtaining a converged solution for the flow and energy first, prior to activate particle injection. Using a single 2.9 GHz CPU, it takes around 6 h to obtain the converged solution of the flow and energy equations. The wall clock time required to reach a stable solution with particles injection and combustion depends on each simulation case, but the average is approximately 24 h.

The refractory walls are made of magnesite (see properties in Table 5), with an internal emissivity set at 0.7. This value was raised with respect to the tabulated value of 0.38 in order to adjust the wall temperature of the kiln since ageing is known to increase the emissivity of refractories, see e.g. [62]. The burner lances are made of carbon steel, whose properties are also set in the database of the solver. Finally, the bricks are assumed to be composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Accordingly, the internal emissivity of the bricks was set to 0.8 [63], and the heat transfer coefficient was estimated at 5 W/m2-K. In order to estimate this value, the authors averaged the result of known Nusselt number correlations for vertical and horizontal walls using the Reynolds number estimated from preliminary simulations.

Finally, a logic diagram is included in Fig. 5 to summarize the overall methodology used in the present work. On the left (see Fig. 5a) are depicted the steps followed to construct the numerical simulation, i.e., from the geometrical representation to the post-processing step, while the Fig. 5b represents the flow chart used to set up the co-firing model.

Results and Discussion

The simulated cases correspond to operation modes tested by the industrial facility and they are summarized in Table 6. The depicted fuel flow rate and the air flow rate were provided by plant operators, as well as the air distribution through the primary/secondary combustion airs and cooling air. Thus, 11% of the air is primary air used to convey the fuel to the kiln through the lances. Around 55% of the air is secondary combustion air that enters through the upper part of the burning shaft of the kiln, while the rest is cooling air entering mainly through the bottom (see Fig. 2). The power input is computed from the heating value of the fuels used (see Table 1) and their mass flow rate. The substitution base for the co-firing case (BMG60) is a mass basis, thus this case corresponds to a blend of fuel composed of 40% coke and 60% biomass. The conditions in fuel blend and air distribution were retrieved from actual operation of the kiln. Note that this choice leads to an important variation in power input with respect to the cases where only coke is used as fuel, due to the large difference in heating values.

Coke Combustion

Coke Combustion with Porous Medium (PM0)

In this section, the results obtained using the porous medium approach are presented, in the case of 100% coke as fuel. The temperature profile is shown in Fig. 5, for the frontal and lateral views of the shaft kiln (see studied views in Fig. 2). The left panel shows that the ignition seems to start far below the burner lances and that the flame front is not appropriately delimited. As a result, the burning shaft (left) presents a low average temperature, well below the required temperature for calcination, i.e., 900 °C. The regenerative shaft, by other side, presents a much higher temperature, although the distribution is not homogeneous. Indeed, there is a clear horizontal gradient, with high temperatures concentrated near the outer wall of the regenerating shaft.

More striking are the differences stressed out in the lateral view (Fig. 6b), which corresponds to the burning shaft. Two narrow streams of air at ambient temperature coming from the lances can be clearly observed. Higher temperatures appear well below the lances and are concentrated in two separated regions. There does not seem to exist any spreading or diffusion of air and temperature to the rest of the burning shaft. This contrasts to what one would intuitively expect to see, since the stones form random networks of channels through which the combustion air, the fuel particles and the gases produced from the combustion process should circulate and diffuse.

The statistical analysis of temperature profiles shows that average temperature is 400 °C and the maximum is 1400 °C. This is very low considering that calcination requires at least 900 °C and that the adiabatic temperature of coke is around 2000 °C. The 3rd quartile of the temperature distribution is 300 °C and the skewness is 1.2. Both data indicate that the distribution is skew toward the left (low temperatures), which is not very realistic. Finally, the kurtosis of the distribution is around 4 (a high value of the kurtosis implies greater deviations or greater outliers). Hence, the temperature profile obtained with the porous model presents several inaccuracies.

The profile of velocities is presented in Fig. 7 in a logarithmic scale, to make its structure apparent. As can be seen, the highest velocities are concentrated at the exit of the lances and the velocity magnitude drops very fast by two orders of magnitude, i.e., from more than 50 m/s to around 2 m/s. This is the anticipated effect of the porous medium, and intuitively, what one expects from a bed of the stones filling in the lime kiln.

Finally, Fig. 8 depicts the trajectories of the fuel particles. Firstly, it may be seen that the fuel particle trajectories are in complete correspondence with the temperature profile in Fig. 6 and explains the lack of turbulence and spreading in the movement of the gases inferred from that figure. Secondly, it seems counterintuitive that particles move in such an orderly way in a medium filled with stones. This observation adds to the fact that if temperatures were as shown in Fig. 6, the process of calcination would be highly uneven, at odds with reality. The main issue is that FLUENT v17.2 code applies a sink of momentum in the region defined as porous medium; this affects the velocities of the particles, but it does not alter their trajectories. Moreover, since the medium is defined as isotropic, the small lateral velocities are almost completely suppressed. For all the reasons mentioned above, it may be concluded that the porous medium model is not an appropriate approach for simulating the presence of lime stones in the PFR shaft kiln.

Coke Combustion with the Brick Model (BM0)

For the reasons just exposed, the authors were led to consider a more realistic representation of the limestone. As a compromise with computer demands, an idealized representation of stones as regular bricks filling the kiln was chosen, as can be seen in Fig. 4. As explained in “Limestone calcination model” section, the distribution of bricks is such that the available fluid volume matches the bed porosity, with the same particle size distribution as the limestone in the actual facility. The properties of limestone are set on the faces of the bricks, being the inner volume empty since no fluid is circulating inside them. The brick’s walls interact thermally with the surrounding gases, being radiation and convection considered in the brick model developed.

As can be seen in Fig. 9, the temperature profile in this model is much more homogeneous than in the porous medium approach (PM0). In the BM model the flame front (with temperatures around 1000 °C) develops earlier, in such a way that the burning shaft (on the left in Fig. 9a) presents a more homogeneous distribution of temperatures. In the regenerative shaft, the temperatures are also more homogeneous than in the porous model (PM0), and the horizontal gradient is inappreciable. There is a striking difference between the right panels of Figs. 9 and 6, the former being very homogeneous in the center of the burning kiln, as one intuitively expects for a homogeneous calcination of the lime. The homogenizing effect achieved is ultimately due to the considerable number of surfaces added, which contribute to heat transfer via convection and radiation. The new surfaces may also explain the rise in maximum temperature with respect to the porous medium model (PM0), although more simulations would be needed to ascertain this point.

The statistical analysis of temperature profiles presents very realistic values. The average and maximum temperatures are 800 °C and 1900 °C, respectively (the average temperature in the calcination zone is around 1000 °C, as expected). The 3rd quartile, the skewness and the kurtosis of the distribution are 1200 °C, 0.1 and 1.4, respectively, thus representing more homogeneous, realistic and consistent values in comparison to the real process.

The logarithmic velocity profile shown in Fig. 10 looks similar to that of the porous model, see Fig. 7. The left panel shows the highest velocities concentrated just at the lances outlet, followed by a sharp and homogeneous drop of around two orders of magnitude. The plane in between the bricks shows a very homogeneous velocity profile, just as in the porous model, but the fluid velocity is higher because there is no impediment to the flow and there is more flow of air since plant operators increased the excess air (see conditions of simulated cases in Table 6).

For the BM0 case, it is interesting to depict the profile of oxygen, in molar fraction (see Fig. 11). It shows that full combustion is delayed until the central region of the burning shaft. However, once combustion starts, the process takes place quite homogeneously inside the burning kiln (except in the area close to the bottom, where cooling air is injected). Close to the exit of the regenerative shaft, the concentration of oxygen slightly increases due to the air supplied through the regenerative lances.

With respect to the fuel particles trajectories, Fig. 12 illustrates that the brick model (BM0) effectively scatters the particles through the burning shaft anchor; this effect can be clearly observed at the outlet of the burner lances. Moreover, it can be seen that there exists a channeling effect in the spaces let by adjacent bricks. These results are more realistic than the previous model (PM0). Also, there is a close correspondence between Figs. 12 and 9, and it is apparent that the correct representation of fuel particle trajectories is crucial in order to achieve an accurate prediction of the temperature and gas composition profile inside the kiln.

By comparing the results obtained with both methods (porous model and bricks model), it may be concluded that the bricks model is a more accurate representation of the bed of stones inside the kiln; hence, it will be used in subsequent calculations.

Coke Combustion Validation

The validation of numerical simulations with experimental data is a challenging task in an industrial environment. On one hand, only few process variables are monitored during furnace operation; mainly outlet temperature and flue gas composition (O2, CO, NOX and SO2). On the other hand, the simulation of some critical process performance indicators is out of the scope of this work (e.g. calcination rate or changes on granulometry of limestone). Finally, the measurements on this kind of plants present several uncertainties due to factors such as variability on raw materials and fuel composition, status of the maintenance of the furnace refractory lining, positioning of the sensors, etc.

For all these reasons, a specific experimental campaign for 100% coke combustion validation has not been carried out (only for co-firing was possible to run specific tests). Instead, an indirect validation of the simulations has been developed. Firstly, the results have been discussed and compared with the plant operator’s rule-of-thumb. Secondly, the CFD simulations have been compared to available literature data, which are summarized in Table 7. In total, ten different research works related to simulation and modelling of lime kilns were found. With respect to the lime kiln technology, only the works of Do [20] and Krause et al. [22] modelled PFR kilns, with co-firing of natural gas and lignite, and with natural gas, respectively). As regards the use of coke as fuel, the works of El-Fakharany [18] and Shagapov et al. [19] reported coke combustion in Mixed Feed Lime Kilns, with higher granulometry and longer combustion times. The other references are related to other kind of lime kilns and different fuels. In all the cases, the temperature ranges in the calcination zone are comparable to the one obtained in the present work, i.e., between 900 and 1300 °C. The maximum temperature obtained in this work is higher than other models mainly for two reasons, peak temperatures of single particles are not simulated in analytical models (but fully modelled on discrete CFD simulations) and coke combustion present higher adiabatic flame temperature than natural gas or lignite. This temperature (1551 °C) is similar to other applications of similar pulverized fuel combustion [25]. Therefore, besides the complexity of all the phenomena involved and the limitation of available data for validation, it may be said that the simulations present a reasonable agreement with plant operation.

Application to Biomass Co-firing (BMGS60)

Once it was determined that the bricks model allows calculating a realistic representation of the gas and fuel particles circulation inside the kiln, the model is applied to a case of co-combustion of coke and biomass. According to a potential operation mode of the plant, the fuel blend is made of 40% coke and 60% biomass, on a mass basis. In this case, the total fuel flow rate was reduced with respect to the BM0 and PM0 cases, which, added to the lower heating value of the biomass, resulted in a much lower power input (see Table 6). Moreover, air excess applied in case of co-firing conditions BMGS60 is extremely high (i.e., 199%). For all the above-mentioned reasons, the temperature profile depicted in Fig. 13 results in lower temperatures and less homogeneous distribution in comparison to temperature profile in BM0 case (see Fig. 9).

The burning shaft shows the effect of the volatiles combustion of biomass in the form of chaotic plumes above the exit of the lances, as well as some “hot spots” below the burner lances. In the regenerative shaft (the right shaft of Fig. 13a), horizontal gradients of temperature appear, which was absent in the case of 100% coke (BM0 case).

As can be seen in Fig. 14, the velocity profile obtained in this BMGS60 case is very similar to that obtained in BM0 case (Fig. 10). In both cases, there is a fast drop of the velocity magnitude at the burner lances outlet. Notwithstanding, the velocity distribution in BMGS60 case is slightly less homogeneous.

On the other hand, the trajectories of fuel particles are depicted in Fig. 15. General features are similar to those of BM0 case (see Fig. 12), but there are also important differences. Firstly, there are more particles since biomass is grinded thinner than coke (see Table 2). Secondly, the particles trajectories are more homogeneously distributed. This effect is found for both shafts and it is more apparent in the lateral view (Fig. 15b). The close correspondence of the particles distribution with the temperature and velocity profiles highlights the importance of particle dynamics to understand combustion process in such technology.

Thus, in the present case, the most important differences are shown in the temperature profile but must be attributed to the mentioned reduction in total fuel flow rate (and thus power input) with respect to BM0 case, and not only to the presence of biomass in the fuel blend.

Comparison of predicted results with experimental data is fundamental for the validation of the CFD simulation tool developed. In comparison to laboratory facilities, the instrumentation available in industrial facilities is usually much reduced and, accordingly, the amount of experimental data for the validation is limited. In this study, available data included the gas temperature at the crossover channel, as well as gaseous emissions at the exhaust gas outlet. In Table 8, the comparison of measurement data and numerical predictions is shown for the BMGS60 case. As can be seen, the numerical predictions are in good correlation with measured data.

The average temperature in the bridge area is very similar for both cases, as does the concentration of O2 at the exit. The calculated NOX emissions at exit are slightly lower, but still in good agreement with measured data. The difference may be due to the conversion routes to NOX formation and/or to values used in the models.

On the other hand, the concentration of CO and SO2 are overpredicted by the numerical model. The computation of combustion product species is based on the two-mixture-fraction non-adiabatic non-premixed combustion model. In this model was created a 5D look-up table with 19 species (simplifying the definition of species emitted during devolatilization and excluding some intermediate species in the gas combustion and SO2 mechanisms). Hence, the computation of CO and SO2 could be subsequently refined with a more detailed look-up table.

It is possible to refine the computation of SO2 using the SOX model implemented in Ansys Fluent. This model includes several sub-models related to detailed kinetics and turbulent interactions. However, the model strongly increases the computational cost, and it has not been used in this work. Moreover, the dry desulphurization process has not been modeled. It is possible that lime (and unreacted) limestone is absorbing partially SO2, resulting in the formation of CaSO4. This is a well-known desulfurization process that takes place in the range of temperatures reached inside the kiln [39].

The excess of CO in the simulation, compared to measured values could be due to two main additional factors. On the one hand, the main product of char oxidation is CO in the simulations (Burnout Stoichiometric Ratio was set at 1.33). This approach is extensively used in literature for biomass/coal co-firing simulations [28, 51,52,53,54]. However, in the present case it probably overestimates the generation of CO. On the other hand, the calcination process has been simplified (see Section “Limestone calcination model”) hence the production of CO2 due to calcination is not computed locally and it is included as a CO2 source with air inlets. This approach reduces the amount of oxygen available in the flame section and increases the amount of CO2 in the kiln that probably inhibits the oxidation of CO to CO2.

The present results show that CFD simulations can serve as a helpful tool for analyzing and improving the operation in an actual and fully-operating lime PFR kiln. This new tool may assist plant operators in the optimization of co-firing conditions, which are crucial to ensure that pollutant emissions are under established limits, the quality of lime produced is satisfactory, and the operational costs are minimized.

Conclusions and Future Work

The main goal of the present work was to develop a CFD model for the combustion process inside a lime calcination PFR shaft kiln that combines accuracy with computation time in obtaining results, since the model is intended to be used as a benchmark to predict optimum operation conditions in an actual plant. Under this perspective, a series of simplifications was introduced. The most important of which concerns the representation of the limestone inside the kiln. In a first approach, the bed of stones is treated as a continuous porous medium with appropriate values of the porosity and permeability. In a second approach, limestone is represented as an arrangement of bricks scattered in the volume of the kiln. The results have shown that the porous medium approach produces unrealistic results of the temperature distribution, as well as the fuel particles trajectories. On the contrary, the second approach renders a more realistic representation of fluid dynamics within the kiln, in line with the expected effect of the actual bed of stones.

The model has been validated with literature data (for a 100% coke simulation) and experimentally validated at industrial scale for a co-combustion case of 40% coke and 60% biomass, on a mass basis. The results show a good agreement for gas temperature, O2 concentration and NOX at the exit. However, the simulations overestimate SO2 and CO concentrations, mainly due to limitations of the model. Overall, considering the limited data for validation, the complexity of the involved phenomena and the hypothesis to reduce the computational cost, the simulations present a good agreement with real operation data.

As a result, the model developed in this study can be used to adjust the operating conditions of PFR kilns, e.g., when the fuel blend is modified or when the PFR kiln power is increased. Notwithstanding, some improvements are recommended in order to refine the CFD simulation results:

-

Smaller bricks and irregular disposition. Smaller bricks would enhance the resemblance to the stones, while an irregular disposition would be more similar to the random distribution of voids through which fuel particles circulate. It would also help to cover the volume that is currently empty next to the lances and the channel.

-

A heat sink term can be added to the bricks in order to model the consumption of energy due to the process of calcination. This could lead to a more accurate prediction of temperatures of the bricks themselves, but also of the gas flowing through the kiln.

-

The calcination degree can be improved by taking into account the distribution of carbon dioxide along the shaft height. Also, it can be included in a time-dependent run in order to account for process history.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article itself.

Abbreviations

- BM:

-

Bricks model

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- CPU:

-

Central processing unit

- DEM:

-

Discrete element model

- GHG:

-

GreenHouse gas

- HPS:

-

High performance shaft

- PFR:

-

Parallel flow regenerative

- PM:

-

Porous medium

- RANS:

-

Reynolds averaged Navier stokes

- TGA:

-

Thermo-gravimetric analysis

- WSGG:

-

Weighted-sum-of-grey-gases

- C D :

-

Drag coefficient

- C G1 :

-

Mixture fraction transport coefficient constant (2.86)

- C G2 :

-

Mixture fraction transport coefficient constant (2.0)

- C p :

-

Specific heat (J/kg K)

- C 1,2,μ :

-

Standard k- ε turbulence model constants

- f :

-

Mixture fraction

- f w,0 :

-

Initial particle moisture mass fraction

- F D :

-

Particle drag force (N)

- G :

-

Mixture fraction variance incident radiation (W)

- h :

-

Enthalpy (kJ/kg)

- I :

-

Radiant intensity (W/m2 sr)

- k :

-

Turbulent kinetic energy (m2 s2)

- n:

-

Refraction index

- Nu:

-

Nusselt number (Nu = hc LC/λ)

- p:

-

Pressure (N /m2)

- Pr:

-

Prandtl number (Pr = μCP/λ)

- qR :

-

Radiative heat absorbed (W/m2)

- R:

-

Ideal gas constant (8.3145 J/mol K)

- Re:

-

Reynolds number (Re = ρvL/μ)

- s:

-

Radiative direction (Iλ)

- Sh:

-

Sherwood number (Sh = km Lc/D)

- Si :

-

Source term of governing equation

- Tm :

-

Mean temperature (K)

- Tp :

-

Particle temperature (K)

- \({\varvec{T}}_{\infty }\) :

-

Gas temperature (K)

- α:

-

Molar absorption coefficient

- \({{\varvec{\upvarepsilon}}}\) :

-

Viscous dissipation (m2 s−3)

- ε p :

-

Particle emissivity

- \({\varvec{\lambda}}\) :

-

Thermal conductivity (W/m K) wavelength (m)

- \({\varvec{\varPhi}}\) :

-

Radiation dispersion

- \({\varvec{\rho}}\) :

-

Density (g/m3)

- \(\Omega^{\prime}\) :

-

Solid angle (rad)

- \({\varvec{\sigma}}\) :

-

Stephan-Boltzmann constant (5.67 × 10–8 W/m2 K4)

- σ k,ε :

-

Standard k- ε turbulence model coefficients

- \({\varvec{\sigma}}_{{\varvec{L}}}\) :

-

Prandtl number \(\left( {\sigma_{L} = \frac{{\mu C_{P} }}{\lambda }} \right)\)

- \({\varvec{\sigma}}_{{\varvec{s}}}\) :

-

Radiative dispersion factor

- \({\varvec{\sigma}}_{{\varvec{T}}}\) :

-

Turbulent Prandtl number \(\left( {\sigma_{T} = \frac{{\mu_{T} C_{P} }}{\lambda }} \right)\)

- \({\varvec{\mu}}\) :

-

Viscosity (kg/m s)

- \(\mu_{v}\) :

-

Kinematic viscosity (kg/m s)

- \(\mu_{{\text{T}}}\) :

-

Turbulent viscosity (kg/m s)

- \({\varvec{\theta}}_{{\varvec{R}}}\) :

-

Radiative temperature (K)\((\theta_{R} = \left( {I/4\sigma )^{4} } \right)\)

References

Oates, J.A.H.: Lime and limestone: chemistry and technology, production and uses. Wiley, Germany (1998)

Lechtenböhmer, S., Nilsson, L.J., Åhman, M., Schneider, C.: Decarbonising the energy intensive basic materials industry through electrification—implications for future EU electricity demand. Energy 115, 1623–1631 (2016)

van Deventer, J.S.J., White, C.E., Myers, R.J.: A roadmap for production of cement and concrete with low-CO2 emissions. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 12(9), 4745–4775 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-020-01180-5

Schorcht, F., Kourti, I., Scalet, B. M., Roudier, S., Delgado Sancho, L.: Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for the Production of Cement, Lime and Magnesium Oxide. European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for prospective technological studies. Report EUR 26129 EN, (2013)

Alcántara, V., et al.: A study case of energy efficiency, energy profile, and technological gap of combustion systems in the Colombian lime industry. Appl. Therm. Eng. 128, 393–401 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.09.018

Meier, A., Gremaud, N., Steinfeld, A.: Economic evaluation of the industrial solar production of lime. Energy Convers. Manag. 46(6), 905–926 (2005)

European Commission. A Roadmap for moving to a competitive low carbon economy in 2050, COM/2011/0112. (2011)

Sagastume Gutiérrez, A., Cogollos Martínez, J.B., Vandecasteele, C.: Energy and exergy assessments of a lime shaft kiln. Appl. Therm. Eng. 51(1), 273–280 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2012.07.013

EuLA—European Lime Association, “Kiln Types. https://www.eula.eu/about-lime-and-applications/production/kiln-types/ (2021)

Piringer, H.: Lime shaft kilns. In: INFUB—11th European Conference on Industrial Furnaces and Boilers, INFUB-11, pp. 75–95. (2017)

Bes, A.: Dynamic process simulation of limestone calcination in normal shaft kilns. Ph.D. Thesis, Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg, (2006)

Belošević, S., Tomanović, I., Beljanski, V., Tucaković, D., Živanović, T.: Numerical prediction of processes for clean and efficient combustion of pulverized coal in power plants. Appl. Therm. Eng. 74, 102–110 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPLTHERMALENG.2013.11.019

Hallak, B., Specht, E., Herz, F., Gröpler, R., Warnecke, G.: Influence of particle size distribution on the limestone decomposition in single shaft kilns. Energy Procedia 120, 604–611 (2017)

Herz, F., Hallak, B., Specht, E., Gröpler, R., Warnecke, G.: Simulation of the limestone calcination in normal shaft kilns. In: 10th European Conference on Industrial Furnaces and Boilers (INFUB), pp. 1–10. (2015)

Filkoski, R.V., Petrovski, I.J., Gjurchinovski, Z.: Energy optimisation of vertical shaft kiln operation in the process of dolomite calcination. Therm. Sci. 22(5), 2123–2135 (2018)

Senegačnik, A., Oman, J., Širok, B.: Annular shaft kiln for lime burning with kiln gas recirculation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 28(7), 785–792 (2008)

Senegačnik, A., Oman, J., Širok, B.: Analysis of calcination parameters and the temperature profile in an annular shaft kiln. Part 2: results of tests. Appl. Therm. Eng. 27(8–9), 1473–1482 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPLTHERMALENG.2006.09.026

El-Fakharany, M.: Process simulation of lime calcination in mixed feed shaft kilns. PhD Thesis, Otto-von-Guericke-Universitat Magdeburg, (2012)

Shagapov, V.S., Burkin, M.V.: Theoretical modeling of simultaneous processes of coke burning and limestone decomposition in a furnace. Combust. Explos. Shock Waves 44(1), 55–63 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10573-008-0008-y

Do, D. H.: Simulation of lime calcination in normal shaft and parallel flow regenerative kilns. PhD Thesis, Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg, (2012)

Owens, W.D., et al.: Thermal analysis of rotary kiln incineration: comparison of theory and experiment. Combust. Flame 86(1), 101–114 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-2180(91)90059-K

Krause, B., et al.: 3D-DEM-CFD simulation of heat and mass transfer, gas combustion and calcination in an intermittent operating lime shaft kiln. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 117, 121–135 (2017)

Krause, B., Liedmann, B., Wiese, J., Wirtz, S., Scherer, V.: Coupled three dimensional DEM–CFD simulation of a lime shaft kiln—calcination, particle movement and gas phase flow field. Chem. Eng. Sci. 134, 834–849 (2015)

Mikulčić, H., von Berg, E., Vujanović, M., Priesching, P., Tatschl, R., Duić, N.: Numerical analysis of cement calciner fuel efficiency and pollutant emissions. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 15(3), 489–499 (2013)

Liu, Y., Shen, Y.: Three-dimensional modelling of charcoal combustion in an industrial scale blast furnace. Fuel 258, 116088 (2019)

Kær, S.K., Rosendahl, L.A., Baxter, L.L.: Towards a CFD-based mechanistic deposit formation model for straw-fired boilers. Fuel 85(5), 833–848 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2005.08.016

van Loo, S., Koppejan, J.: Biomass combustion modelling workshop. In: van Loo, S., Koppejan, J. (eds.) International energy agency, bioenergy agreement task 19. Seville, Spain (2000)

Pallarés, J., Gil, A., Cortés, C., Herce, C.: Numerical study of co-firing coal and Cynara cardunculus in a 350 MWe utility boiler. Fuel Process. Technol. 90(10), 1207–1213 (2009)

Rezeau, A., Díez, L.I., Royo, J., Díaz-Ramírez, M.: Efficient diagnosis of grate-fired biomass boilers by a simplified CFD-based approach. Fuel Process. Technol. 171, 318–329 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2017.11.024

Guo, F., Zhong, Z.: Simulation and analysis of coal and biomass pellet in fluidized bed with hot air injection. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 11(3), 1115–1123 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-018-0309-7

Ghenai, C., Janajreh, I.: CFD analysis of the effects of co-firing biomass with coal. Energy Convers. Manag. 51(8), 1694–1701 (2010)

Dong, W., Blasiak, W.: CFD modeling of ecotube system in coal and waste grate combustion. Energy Convers. Manag. 42(15–17), 1887–1896 (2001)

Li, J., Singer, S.L.: An efficient coal pyrolysis model for detailed tar species vaporization. Fuel Process. Technol. 171, 248–257 (2018)

Mazza, G.D., Soria, J.M., Gauthier, D., Reyes Urrutia, A., Zambon, M., Flamant, G.: Environmental friendly fluidized bed combustion of solid fuels: a review about local scale modeling of char heterogeneous combustion. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 7(2), 237–266 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-015-9461-5

Mungyeko Bisulandu, B.-J.R., Marias, F.: Modeling of the thermochemical conversion of biomass in cement rotary kiln. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 12(2), 1005–1024 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-020-01001-9

Macphee, J. E., Jermy, S. M. M., Tadulan, E.: CFD modelling of pulverized coal combustion in a rotary lime kiln. In: 7th International Conference on CFD in the minerals and process industries, pp. 1–6 (2009)

“PFR kilns for soft-burnt lime.” https://www.maerz.com/portfolio/pfr-kilns-for-soft-burnt-lime/?lang=en. Accessed 16 Jul 2021

Wang, Y., Lin, S., Suzuki, Y.: Study of limestone calcination with CO2 capture: decomposition behavior in a CO2 atmosphere. Energy Fuels 21(6), 3317–3321 (2007)

Moropoulou, A., Bakolas, A., Aggelakopoulou, E.: The effects of limestone characteristics and calcination temperature to the reactivity of the quicklime. Cem. Concr. Res. 31(4), 633–639 (2001)

Spliethoff, H., Hein, K.R.G.: Effect of co-combustion of biomass on emissions in pulverized fuel furnaces. Fuel Process. Technol. 54(1–3), 189–205 (1998)

ANSYS Inc., ANSYS Fluent User’s Guide, Release. Accessed 17 Feb 2016

Mohammadpour, K., Woche, H., Specht, E.: CFD simulation of parallel flow mixing in a packed bed using porous media model and experiment validation. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 53(3), 475–484 (2017)

Mikulčić, H., et al.: The application of CFD modelling to support the reduction of CO2 emissions in cement industry. Energy 45(1), 464–473 (2012)

Mikulčić, H., Vujanović, M., Duić, N.: Improving the sustainability of cement production by using numerical simulation of limestone thermal degradation and pulverized coal combustion in a cement calciner. J. Clean. Prod. 88, 262–271 (2015)

Klason, T., Bai, X.S., Bahador, M., Nilsson, T.K., Sundén, B.: Investigation of radiative heat transfer in fixed bed biomass furnaces. Fuel 87(10–11), 2141–2153 (2008)

Liu, F., Swithenbank, J., Garbett, E.S.: The boundary condition of the PN-approximation used to solve the radiative transfer equation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 35(8), 2043–2052 (1992)

Herce, C., de Caprariis, B., Stendardo, S., Verdone, N., De Filippis, P.: Comparison of global models of sub-bituminous coal devolatilization by means of thermogravimetric analysis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 117(1), 507–516 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-014-3648-z

Brillard, A., Brilhac, J.F., Valente, M., Alberto, J., Brillard, C.A.: Modelization of the grape marc pyrolysis and combustion based on an extended independent parallel reaction and determination of the optimal kinetic constants. Comput. Appl. Math. 36, 89–109 (2017)

Baum, M.M., Street, P.J.: Predicting the combustion behaviour of coal particles. Combust. Sci. Technol. 3(5), 231–243 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1080/00102207108952290

Field, M.A.: Rate of combustion of size-graded fractions of char from a low-rank coal between 1200°K and 2000°K. Combust. Flame 13(3), 237–252 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-2180(69)90002-9

Bhuiyan, A.A., Naser, J.: Computational modelling of co-firing of biomass with coal under oxy-fuel condition in a small scale furnace. Fuel 143, 455–466 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2014.11.089

Drosatos, P., Nikolopoulos, N., Karampinis, E., Strotos, G., Grammelis, P., Kakaras, E.: Numerical comparative investigation of a flexible lignite-fired boiler using pre-dried lignite or biomass as supporting fuel. Renew. Energy 145, 1831–1848 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.07.071

Bonefacic, I., Frankovic, B., Kazagic, A.: Cylindrical particle modelling in pulverized coal and biomass co-firing process. Appl. Therm. Eng. 78, 74–81 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.12.047

Wang, X., et al.: Numerical study of biomass Co-firing under Oxy-MILD mode. Renew. Energy 146, 2566–2576 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.08.108

Du, Y., Wang, C., Lv, Q., Li, D., Liu, H., Che, D.: CFD investigation on combustion and NOx emission characteristics in a 600MW wall-fired boiler under high temperature and strong reducing atmosphere. Appl. Therm. Eng. 126, 407–418 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.07.147

Hurt, R.H., Mitchell, R.E.: Unified high-temperature char combustion kinetics for a suite of coals of various rank. Symp. Combust. 24(1), 1243–1250 (1992)

Widmann, E., Scharler, R., Stubenberger, G., Obernberger, I.: Release of NOx precursors from biomass fuel beds and application for CFD-based NOx postprocessing with detailed chemistry. In: Proc. of the 2nd World Conference and Exhibition on Biomass for Energy, Industry and Climate Protect, pp. 1384–1387 (2004)

Brunner, T., Biedermann, F., Kanzian, W., Evic, N., Obernberger, I.: Advanced biomass fuel characterization based on tests with a specially designed lab-scale reactor. Energy Fuels 27(10), 5691–5698 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/ef400559j

Bluhm-Drenhaus, T., Simsek, E., Wirtz, S., Scherer, V.: A coupled fluid dynamic-discrete element simulation of heat and mass transfer in a lime shaft kiln. Chem. Eng. Sci. 65(9), 2821–2834 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CES.2010.01.015

Scherer, V., Wirtz, S., Krause, B., Wissing, F.: Simulation of reacting moving granular material in furnaces and boilers an overview on the capabilities of the discrete element method. Energy Procedia 120, 41–61 (2017)

Chen, L., Yong, S.Z., Ghoniem, A.F.: Oxy-fuel combustion of pulverized coal: characterization, fundamentals, stabilization and CFD modeling. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 38(2), 156–214 (2012)

Touloukian, Y.S., DeWitt, D.P.: Thermal radiative properties: metallic elements and alloys (thermophysical properties of matter). Springer, Berlin (1970)

Quinn Brewster, M.: Thermal radiative transfer and properties. Wiley, Hoboken (1992)

ANSYS Inc., ANSYS Fluent Theory Guide, Release. Accessed 17 Feb 2016

Stern, F., Wilson, R., Shao, J.: Quantitative V&V of CFD simulations and certification of CFD codes. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 50, 1335–1355 (2006)

Acknowledgements

The authors kindly acknowledge data-sharing from CIARIES plant in La Puebla de Albortón, Zaragoza (Spain).

Funding

Open access funding provided by ENEA within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This work was developed as part of the STEAMBIO project, funded by EC Horizon 2020 Programme and SPIRE public private partnership under Grant Agreement No. 636865. Carlos Herce is supported by ENEA-Italian Ministry of Ecological Transition under the National Electrical System Research Program “Ricerca del Sistema Elettrico Nazionale”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Governing Equations of CFD Model

The CFD governing equations used in this work are implemented in ANSYS Fluent commercial code. No modifications have been made and more details can be found in [41, 64] (see Table

9).

Appendix 2 Independence Mesh Study

The goal of this section is to study to which degree the results obtained depend on the mesh used to run the calculations. To this end, simulations of the same case have been run with three different meshes obtained by refining and coarsening a medium sized mesh that has been used to carry out the simulations in this document. The case chosen for this verification is the bricks model using coke as fuel. To carry out a mesh verification it would be ideal to have three meshes with very different sizes, i.e., number of cells [65]. However, in this particular case, where the volume essentially consists of narrow channels between the bricks it is very difficult to coarse or refine the mesh to a large extent. By one hand, regarding coarsening, the minimum number of cells in a channel is three, otherwise flow is not well defined. By other hand, when coarsening, introducing many elements in the channel distorts them, which negatively affects the solution, instead of improving it as should be for a thin mesh. For these reasons we are forced to consider a not very wide span in mesh sizes.

In Table

10 we have summarized the key parameters of the three meshes used along with relevant temperatures inside kiln for comparison. The number of cells is the number of small volumes in which the mesh is subdivided, while h is the average linear size of the cells. The ratio of the linear sizes, coarser to medium and medium to refined, gives a more intuitive idea of the relative size of the meshes. Note that the refined mesh differs from the medium more than does the coarser, this is due to the limitation mentioned above regarding the minimum number of cells in a channel.

Next, we consider the average temperature of the front and lateral planes that we have used for comparison through this document, the average temperature of all the bricks, the temperature at the exit of the kiln and the average temperature of the gas inside the kiln. Finally, columns 5 and 6 show the relative difference (expressed as a percentage) between the result obtained with meshes medium and coarser, and medium and refined, respectively.

It is immediately apparent that the results are less different between refined and medium meshes, than between the latter and the coarser. Roughly, the difference is an order of magnitude smaller, expressed as a percentage. This is even more telling taking into account that refined and medium meshes differ more, as evidenced by their ratio, than does the coarser respect to the medium. By comparing the results of meshes medium and refined, one can conclude that the medium mesh is robust, so refining leads to almost negligible improvements while increasing the complexity of the case and the calculation time. By other hand, simplifying by coarsening the mesh leads to differences of 10% in the results, which given the comparison medium-refined, have to be considered less accurate.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arévalo, R., Rezeau, A. & Herce, C. CFD Analysis of Co-firing of Coke and Biomass in a Parallel Flow Regenerative Lime Kiln. Waste Biomass Valor 13, 4925–4949 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-022-01833-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-022-01833-7