Abstract

In the paper the data set from the experimental study on the influence of a fuel blend composition on the efficiency of steam co-gasification process was explored with the application of the principal component analysis and the hierarchical clustering analysis. Based on the analysis the synergy effects observed in the steam co-gasification process at the temperature of 700 and 900 °C were interpreted. In the co-gasification tests the significant differences between studied biomass types (Miscanthus Giganteus and Sida Hermaphrodita) were observed. The more pronounced synergy effects were reported in co-gasification of coal and Sida Hermaphrodita biomass blends than for coal and Miscanthus Giganteus biomass. Furthermore, more significant synergy effects in co-gasification of coal and Sida Hermaphrodita biomass were observed at lower temperature. A further, in-depth analysis of the relationships between the physical and chemical parameters of fuels and the product gas quality and volume enabled to determine the biomass content in a fuel blend, and the thermal conditions optimal for hydrogen-rich gas production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The utilization of biomass/biowaste, as a “zero-emission” energy source, in gasification systems is still negligible, mainly because of the limited supplies of biomass, resulting in a relatively small scale and poor cost-effectiveness of such systems. The technical problems inherently combined with the physical and chemical properties of biomass, such as tars formation and corrosion, are also disadvantageous. On the other hand, the conventional processes of thermochemical conversion of solid fuels, especially coal, are significant sources of emission of air contaminants, like particulates, carbon dioxide, sulfur and nitrogen oxides. Therefore, the process of co-gasification is expected to be the desired alterative to coal or biomass/biowaste gasification, with the particularly attractive option of hydrogen-rich gas production [1]. The process of steam co-gasification of coal and biomass is considered to be offering the benefits of scale (abundant reserves of a fossil fuel), decreased CO2 emission, since the “zero-emission” fuel is co-utilized, and production of a prospective, clean and environment friendly energy carrier − hydrogen. Numerous studies have been reported so far on co-gasification of various fuel blends in different gasifier configurations, but further research is still needed before a wide implementation of co-gasification is possible [2–4]. The research in the field of thermochemical processing of biomass is focused in particularly on fuel blends composition, optimization of a feeder design, selection of the adequate catalysts and operating conditions for gasification/co-gasification process [4–9]. A proper biomass pre-treatment is also crucial for the gasification process efficiency. The synergy effects in co-processing of biomass with other fuels have also gained a research interest recently [10–20] and further investigations are claimed to be needed for the in-depth understanding of the phenomena [21]. These effects include predominantly the enhanced process efficiency [10, 16, 20] and increased fuel reactivity [15, 17] observed in co-gasification.

In the paper the effects of steam co-gasification of Miscanthus Giganteus (MXG) and Sida Hermaphrodita (SH) biomass with coal at 700 and 900 °C are presented. For a more in-depth analysis of the relationships between the physical and chemical parameters of fuels and the product gas quality in steam gasification at various temperatures the chemometric methods of the principal component analysis (PCA) and the hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) were applied. This allowed to determine the optimal biomass content in a fuel blend, and the thermal conditions for the hydrogen-rich gas production.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Stand

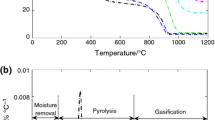

The experimental study on steam gasification and co-gasification of coal and biomass was conducted in a laboratory scale installation with a fixed bed reactor (see Fig. 1) [22, 23].

The tested hard coal samples (HC1, HC2, and HC3) were supplied by three different coal mines located in the Upper Silesian Coal Basin (Poland). The tested biomass samples, Miscanthus X Giganteus (MXG) and Sida Hermaphrodita (SH) were provided by plantation in Főhren (Germany) and Department of Agricultural Sciences in Zamość of University of Life Sciences in Lublin (Poland), respectively. The proximate and ultimate analyses of the tested fuels are presented in Table 1. The analyses were conducted in the accredited laboratory of the Central Mining Institute according to the relevant standards: PN-G-04560:1998 (contents of moisture and ash), PN-G-04516:1998 (contents of volatiles), PN-ISO 1928:2002 (heat of combustion and calorific value), PN-G-04571:1998 (contents of carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen), PN-G-04584:2001 (content of sulfur) and PN-G-04516:1998 (content of fixed carbon).

Studied coal and biomass samples were dried, ground and sieved to the fractions of particle size below 0.2 mm for coal and below 3 mm for biomass. The experiments were conducted in two stages. In the first one a sample of 10 g of coal or biomass was gasified with steam. In the second one fuel blends composed of coal and 20 or 40%w/w of biomass (MXG or SH) of the total mass of 10 g were processed in steam co-gasification. The gasification and co-gasification tests were performed at 700 and 900 °C under atmospheric pressure. The fuel samples tested were fed into the fixed bed reactor, and heated up in nitrogen atmosphere to the set process temperature (700 or 900 °C). After temperature stabilization steam as a gasification agent was injected with a flow rate of approximately 5 × 10− 2 cm3 s− 1. A dried and cooled product gas was analyzed on-line with the application of a gas chromatograph Agilent 3000 A (gas composition analysis) and a flow meter (gas volume).

Chemometric Methods of Data Analysis

In the chemometric analysis of the data studied the PCA and the HCA methods were applied. The studied experimental data set was organized into matrix X(17 × 20), where rows represent studied fuel samples (see Table 2) and columns correspond to the studied parameters listed in Table 3. The studied data organized into matrix X(17 × 20) included measurements performed within different magnitude ranges, and therefore it was centered and standardized before the PCA and HCA models were constructed [24].

The PCA is a chemometric technique of exploratory analysis of multivariate data sets [25–27] which allows to reduce data dimensionality, its visualization and interpretation. It decomposes the initial data organized in matrix X(m × n) into two matrices, S(m × fn) and D(n × fn), called score and loading matrices, respectively. M and n denote the number of objects and parameters, respectively, whereas fn denotes the number of significant factors called the principal components (PCs). Score and loading matrices are orthogonal. Providing that the reduction of data dimensionality is effective, it is possible to apply score vectors and loading vectors (i.e. the columns of matrices S and D, respectively) to visualize and interpret the relationships between the objects and the parameters in matrix X.

The HCA [24, 28–33] enables analyzing the structure of the data organized in matrix X(m × n) by tracing the similarities between the examined objects in the parameter space, and between the measured parameters in the object space. The results of the HCA are presented in the form of dendrograms differing in terms of the applied similarity measure between objects, as well as the way the similar objects are connected. For the continuous variables the Euclidean distance or the Manhattan distance are the similarities measures most often applied, whereas among the methods of similar objects clustering the single linkage, the complete linkage, the average linkage, the centroid linkage and the Ward’s linkage methods may be distinguished [34, 35]. The HCA does not allow for simultaneous tracing of the relationship between objects and parameters. This could be, however, overcome by complementing the HCA with a color map of the experimental data, enabling a more in-depth interpretation of the data structure, and tracing the similarities and differences between the clusters on a dendrogram [36, 37].

Results and Discussion

The total volumes of the main gas components generated in 1-h tests of coal and biomass gasification and co-gasification at the temperature of 700 and 900 °C are presented in Fig. 2.

The temperature is the crucial parameter in the endothermic processes of gasification and co-gasification. The total gas volumes generated in hard coal and biomass steam gasification and co-gasification at 900 °C were higher than at 700 °C. The average total gas volume increased in all studied gasification and co-gasification tests of approximately 11.52% with the temperature rise from 700 to 900 °C. At the temperature of 700 °C relatively low carbon conversion was observed. Moreover, the reversed Boudouard reaction led to the increase in carbon monoxide content in the product gas and a minor influence of the water gas shift reaction (WGS) on the ratio of carbon monoxide to carbon dioxide could be observed. At the temperature of 900 °C the reverse WGS reaction was observed resulting in the decreased content of carbon dioxide in the product gas. Based on the experimental results presented the synergy effects in steam co-gasification of coal and biomass could be also observed. These included the increase in the total gas volume in co-gasification in comparison with the values reported for gasification of coal and biomass separately (see Fig. 3). Significant differences between studied biomass samples (MXG and SH) were also observed; the more profound synergy effect was observed in co-gasification of coal with Sida Hermaphrodita biomass than for fuel blends containing Miscanthus Giganteus biomass (see Fig. 3).

Furthermore, for SH blends stronger synergy effects were observed at lower process temperature. The synergy effects consisting in an increase in product gas yields in co-pyrolysis and co-gasification of coal and biomass have been previously reported in the literature [3, 7, 16, 20]. The differences in the observed synergy effects for coal blends with different biomass could be attributed to the differences in ash content and composition, in particularly in terms of metal oxides content in biomass samples (see Table 4).

The alkali and alkali earth metals may present a potential catalytic activity in the gasification process [1, 5, 8, 16, 36]. Significant differences between MXG and SH were observed in terms of calcium, potassium, manganese and sodium content of catalytic potential in co-gasification process. Miscanthus Giganteus biomass was characterized by lower contents of these elements in ash than Sida Hermaphrodita, which was reflected in weaker synergy effects observed in co-gasification of coal with MXG than in co-processing of coal and SH biomass.

The chemometric methods of PCA and HCA were applied in a more in-depth analysis of the influence of a fuel blend composition, physical and chemical parameters of fuels tested and process temperature on process efficiency, and the synergy effects observed in steam co-gasification. The PCA model with four significant PCs described 95.35% of the data variance. Score plots and loading plots obtained as a result of the analysis are presented in Fig. 4.

The PC1 which described 60.32% of the total variance revealed the differences between MXG and SH biomass (objects nos 4 and 5) and all the remaining fuel samples resulting from the highest content of volatiles and hydrogen in a sample (parameters nos 3 and 8) and the lowest heat of combustion, calorific value, content of nitrogen and fixed carbon, as well as the lowest total gas, hydrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide volumes at 700 and 900 °C (parameters nos 4, 5, 9–14 and 16–19). Moreover, four groups of fuel samples and the uniqueness of HC1 (object no. 1) could be distinguished along PC1. The first group was composed of biomass samples (objects nos 4 and 5), the second of HC2 blends with 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass, and HC3 blends with 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass (objects nos 12, 13, 16 and 17). The third group collected HC1 blends with 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass, HC2 blends with 20%w/w MXG and SH, and HC3 blends with 20%w/w of MXG and SH biomass (objects nos 8, 9, 10, 11, 14 and 15). The fourth group was composed of HC2, HC3 and HC1 blends with 20%w/w of MXG and SH biomass (objects 2, 3, 6 and 7, respectively). HC1 (object no. 1) differed from all these groups mainly because of the highest heat of combustion, calorific value, the lowest content of nitrogen and fixed carbon in a sample, and the lowest total gas, hydrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide volumes at 700 and 900 °C (parameters nos 4, 5, 9–14 and 16–19, respectively). The PC2 (describing 17.76% of the total variance) additionally reflected the difference between sample HC1 and HC1 blends of 20 and 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass content (objects nos 1, 6, 7, 8 and 9), and all the remaining fuel samples. Based on the loading plots these differences could be attributed to the relatively high carbon content (parameter no. 7) and low ash content in a sample (parameter no. 2). The PC2 revealed also the uniqueness of sample HC2 resulting from the highest ash content (parameter no. 2) among all the studied fuel samples. The PC3, describing 14.23% of the total variance, showed the uniqueness of sample HC3 and blends of HC3 of 20%w/w of MXG biomass content (objects nos 3 and 14), whereas the PC4, describing 3.04% of the total variance, was constructed mainly due to the difference between the HC3 blend of 40%w/w of MXG biomass content (object no. 16) and blends of HC1 with 40%w/w of SH biomass and HC2 with 20%w/w of MXG biomass content (objects nos 9 and 10). The uniqueness of sample HC3 and HC3 blends with 20%w/w of MXG biomass (objects nos 3 and 14) could be attributed to the highest moisture content in a sample (parameter no. 1) and the lowest content of ash and nitrogen in a sample (parameters nos 2 and 9). The HC3 blend with 40%w/w of MXG biomass (object no. 16) was characterized by relatively high content of the total moisture, and sulfur in a sample, high volume of carbon monoxide produced at 900 °C (parameters nos 1, 6 and 18) and low volume of methane generated in co-gasification at 900 °C (parameter no. 20).

The loading plots revealed a positive correlation between the volatiles and hydrogen content in a sample (parameters nos 3 and 8); heat of combustion, calorific value, and volume of carbon dioxide at 700 and 900 °C (parameters nos 4, 5, 14 and 19); as well as content of nitrogen in a sample, and the total gas and hydrogen volumes at 700 and 900 °C (parameters nos 9, 11, 12, 16 and 17). Furthermore, a negative correlation was observed between volatiles and hydrogen content in a sample (parameters nos 3, 8), and nitrogen content in a sample, the total gas and hydrogen volumes at 700 and 900 °C (parameters nos 9, 11, 12, 16 and 17).

An efficient compression of the studied data was not possible with the application of the PCA, as the standard method of data exploration, and the results obtained required investigation of many two-dimensional plots. All the detailed conclusions presented above allowed extracting only general information on the analyzed experimental data. Therefore, the HCA method was applied to further explore the studied data organized in the matrix X(17 × 20). It allowed to reveal the internal data structure and thereof its clustering tendency. It enabled to analyze the data structure by tracing the similarities between studied fuel samples (objects) in the parameters space and parameters in the objects space. The Euclidean distance was applied as the similarity measure. The results of the analysis (see Fig. 5) were presented in the form of dendrograms constructed with the Ward’s linkage method.

Dendrogram of (a) 17 studied fuel samples in the space of 20 measured parameters (listed in Table 3) and (b) parameters in the objects space with (c) the color map of the studied data sorted according to the Ward linkage method

The dendrogram presenting the studied fuel samples in the space of 20 measured parameters (see Fig. 5a) revealed three main clusters. Cluster A collected coal samples HC2, and HC3, blends of HC2 with 20 and 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass, as well as blends of HC3 with 20 and 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass (objects nos 2, 3, 10–17). Cluster B grouped coal sample HC1, and blends of HC1 with 20 and 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass (objects nos 1 and 6–9), while cluster C was composed of MXG and SH biomass samples (objects nos 4 and 5). Furthermore, in cluster A two sub-clusters could be distinguished:

-

Sub-cluster A1 composed of coal sample HC2, blends of HC2 with 20 and 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass, and blends of HC3 with 20%w/w of SH biomass (objects nos 2, 10–13 and 15), and

-

Sub-cluster A2 grouping coal sample HC3, blends of HC3 with 20%w/w of MXG biomass, and blends of HC3 with 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass (objects nos 3, 14, 16 and 17).

The dendrogram constructed for the studied parameters in the objects space revealed four main groups (see Fig. 5b):

-

Group A composed of parameters nos 4, 5, 7, 10, 14 and 19, representing heat of combustion, calorific value, carbon and fixed carbon content in a sample, and carbon dioxide volume at 700 and 900 °C, respectively,

-

Group B including parameters nos 2, 9, 11, 12, 13, 16, 17 and 18, representing content of ash, and nitrogen in a sample, as well as the total gas, hydrogen and carbon monoxide volumes at 700 and 900 °C, respectively,

-

Group C collecting parameters nos 1, 6, 15 and 20, representing the total moisture and sulfur content in a sample, and methane volume at 700 and 900 °C, respectively, and

-

Group D composed of parameters nos 3 and 8, representing the volatiles and hydrogen content in a sample, respectively.

The dendrogram showed in Fig. 5a presented the data structure, but did not allow investigating the observed patterns in terms of studied parameters. To solve this problem the HCA was complemented with a color map of experimental data sorted according to the specific order of the studied fuel samples (objects) and parameters presented in Fig. 5a, b, respectively. The analysis of the dendrogram presenting studied fuels in the space of the measured parameters with the color data map (see Fig. 5c) enabled a more in-depth investigation of the resulting clustering tree.

Based on the interpretation of the dendrogram of objects in the space of measured parameters, and the color map of the experimental data it was concluded that coal samples HC2 and HC3, blends of HC2 with 20 and 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass, as well as blends of HC3 with 20 and 40%w/w MXG and SH biomass (objects nos 2, 3, 10–17) collected in cluster A were characterized by low volatiles and hydrogen content in a sample (parameters nos 3 and 8). The uniqueness of coal sample HC2, blends of HC2 with 20 and 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass, and blends of HC3 with 20%w/w of SH biomass (objects nos 2, 10–13 and 15) grouped in sub-cluster A1 was attributed to high ash content in a fuel sample (parameter no. 2), low heat of combustion, calorific value, fixed carbon content, and carbon dioxide volume at 700 and 900 °C (parameters nos 4, 5, 10, 14 and 19) and the lowest carbon content in a sample (parameter no. 7). Furthermore, the distinctiveness of coal sample HC2 was reported resulting from the highest ash content (parameter no. 2), relatively high nitrogen content in a sample, as well as high total gas, hydrogen, and carbon monoxide volumes at 700 and 900 °C (parameters nos 9, 11–13 and 16–18, respectively). Coal sample HC3, blends of HC3 with 20%w/w of MXG biomass, and blends of HC3 with 40%w/w of MXG and SH biomass (objects nos 3, 14, 16 and 17) collected in sub-cluster A2 were characterized by high total moisture and sulfur content in a fuel sample as well as methane volume at 700 °C (parameters nos 1, 6 and 15). The coal sample HC3 (object no. 3) was characterized by the highest total moisture and sulfur content in a sample (parameters nos 1 and 6) and high heat of combustion, calorific value and fixed carbon content in a sample (parameters nos 4, 5 and 10), whereas the blend of HC3 with 20%w/w of MXG biomass (object no. 14) was unique due to the highest methane volume at 700 °C (parameter no.15).

Coal sample HC1, and blends of HC1 with 20 and 40% of MXG and SH biomass (objects nos 1 and 6–9) collected in cluster B were characterized by high heat of combustion, calorific value, carbon and fixed carbon content in a sample, and carbon dioxide volume at 700 and 900 °C (parameters nos 4, 5, 7, 10, 14 and 19) as well as low total moisture and sulfur content in a sample and methane volume at 700 °C (parameters nos 1, 6 and 15). Moreover, the uniqueness of coal sample HC1 was observed resulting from the highest heat of combustion, calorific value, carbon, nitrogen and fixed carbon content in a fuel sample and the total gas, hydrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide volumes at 700 and 900 °C (parameters nos 4, 5, 7, 9–14, 16–19).

MXG and SH biomass samples belonging to cluster C (objects nos 4 and 5) differed from the remaining studied samples largely because of the lowest ash, nitrogen and fixed carbon content in a sample, the lowest heat of combustion and calorific value as well as the total gas, hydrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide volumes at 700 and 900 °C (parameters nos 2, 4, 5, 9–14 and 16–19), as well as the highest volatiles and hydrogen content in a fuel sample (parameters nos 3 and 8). Furthermore, the uniqueness of SH biomass was observed attributed to the relatively high total moisture content in a sample, and high methane volume at 700 °C (parameters nos 1 and 15).

Conclusions

The PCA enabled an in-depth analysis of the influence of a fuel blend composition, physical and chemical parameters of fuels tested and process temperature on gasification process efficiency. The HCA method was also applied to analyze the clustering tendency of the studied data set and to trace the similarities between studied fuel samples in the parameters space and parameters in the objects space. The average total gas volumes produced in coal and biomass steam gasification and co-gasification at 900 °C were higher than the respective values reported at 700 °C. The increase in the total gas volumes in co-gasification of coal with 20 and 40%w/w of biomass was observed in comparison with the values expected based on the results reported for gasification of coal and biomass separately. The significant differences between studied biomass samples were observed, reflected in the stronger synergy effect reported in co-gasification of blends of coal and Sida Hermaphrodita biomass than for blends of coal and Miscanthus Giganteus biomass. These differences may be attributed to various contents of selected metals in samples tested. Furthermore, more profound synergy effects were observed in co-gasification of coal blends with Sida Hermaphrodita biomass at 700 °C than at 900 °C, with the maximum value of the relative total gas volume increase observed for a blend containing 40%w/w of Sida Hermaphrodita biomass at 700 °C. The maximum hydrogen volume generated in co-gasification was reported for fuel blends containing 20%w/w of Sida Hermaphrodita biomass at both tested temperatures.

References

Kirkels, A.F., Verbong, G.P.J.: Biomass gasification: still promising? A 30-year global overview. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 15, 471–481 (2011)

Li, K., Zhang, R., Bi, J.: Experimental study on syngas production by co-gasification of coal and biomass in a fluidized bed. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 35, 2722–2726 (2010)

Collot, A.G., Zhuo, Y., Dugwell, D.R., Kandiyoti, R.: Co-pyrolysis and co-gasification of coal and biomass in bench-scale fixed-bed and fluidized bed reactors. Fuel. 78, 667–679 (1999)

Brar, J.S., Singh, K., Wang, J., Kumar, S.: Co-gasification of coal and biomass: a review. Int. J. For. Res. (2012). doi: 10.1155/2012/363058

Pinto, F., Lopes, H., Andre, R.N., Gulyurtlu, I., Cabrita, I.: Effect of catalysts in the quality of syngas and by-products obtained by co-gasification of coal and wastes. 1. Tars and nitrogen compounds abatemen. Fuel. 86, 2052–2063 (2007)

Pinto, F., Franco, C., Lopes, H., Andre, R.N., Gulyurtlu, I., Cabrita, I.: Effect of used edible oils in coal fluidised bed gasification. Fuel. 84, 2236–2247 (2005)

Lapuerta, M., Hernandez, J.J., Pazo, A., Lopez, J.: Gasification and co-gasification of biomass wastes: effect of the biomass origin and the gasifier operating conditions. Fuel Process. Technol. 89, 828–837 (2008)

Michel, R., Rapagnà, S., Di Marcello, M, Burg, P., Matt, M., Courson, C., Gruber, R.: Catalytic steam gasification of Miscanthus X giganteus in fluidised bed reactor on olivine based catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol. 92, 1169–1177 (2011)

Zhu, W., Song, W., Lin, W.: Catalytic gasification of char from co-pyrolysis of coal and biomass. Fuel Process. Technol. 89, 890–896 (2008)

Miccio, F., Piriou, B., Ruoppolo, G., Chirone, R.: Biomass gasification in a catalytic fluidized reactor with beds of different materials. Chem. Eng. J. 154, 369–374 (2009)

Moliner, R., Suelves, I., Lazaro, M.J.: Synergetic effects in the copyrolysis of coal/petroleum residue mixture by pyrolysis/gas chromatography: influence of temperature, pressure, and coal nature. Energ. Fuel. 12, 963–968 (1998)

Brage, C., Yu, Q., Chen, G., Sjostrom, K.: Tar evolution profiles obtained from gasification of biomass and coal. Biomass Bioenerg. 18, 87–91 (2000)

Yuan, S., Dai, Z., Zhou, Z., Chen, X., Yu, G., Wang, F.: Rapid co-pyrolysis of rice straw and a bituminous coal in a high-frequency furnace and gasification of the residual char. Bioresour. Technol. 109, 188–197 (2012)

Sonobe, T., Worasuwannarak, N., Pipatmanomai, S.: Synergies in co-pyrolysis of Thai lignite and corncob. Fuel Process. Technol. 89, 1371–1378 (2008)

Sjöstrom, K., Chen, G., Yu, Q., Brage, C., Rosen, C.: Promoted reactivity of char in cogasification of biomass and coal: synergies in the thermochemical process. Fuel. 78, 1189–1194 (1999)

Howaniec, N., Smoliński, A.: Effect of fuel blend composition on the efficiency of hydrogen-rich gas production in co-gasification of coal and biomass. Fuel. 128, 442–450 (2014)

Howaniec, N., Smoliński, A.: Steam co-gasification of coal and biomass—synergy in reactivity of fuel blends chars. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 38, 16152–16160 (2013)

Suelves, I., Lazaro, M.J., Moliner, R.: Synergetic effects in the copyrolysis of samca coal and a model aliphatic compound studied by analytical pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 65, 197–206 (2002)

Fei, J., Zhang, J., Wang, F., Wang, J.: Synergistic effects on copyrolysis of lignite and high-sulfur swelling coal. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 95, 61–67 (2012)

André, R.N., Pinto, F., Franco, C., Dias, M., Gulyurtlu, I., Matos, M.A.A., Cabrita, I.: Fluidised bed co-gasification of coal and olive oil industry wastes. Fuel. 84, 1635–1644 (2005)

Brar, J.S., Singh, K., Wang, J., Kumar, S.: Co-gasification of coal and biomass: a review. Int. J. Forest Res. (2012). doi: 10.1155/2012/363058

Howaniec, N., Smoliński, A., Cempa-Balewicz, M.: Experimental study of nuclear high temperature reactor excess heat use in the coal and energy crops co-gasification process to hydrogen-rich gas. Energy. 84, 455–461 (2015)

Smoliński A.: Coal char reactivity as a fuel selection criterion for coal-based hydrogen-rich gas production in the process of steam gasification. Energ. Convers. Manag. 52, 37–45 (2011)

Vandeginste, B.G.M., Massart, D.L., Buydens, L.M.C., de Jong, S., Lewi, P.J., Smeyers-Verbeke, J.: Handbook of chemometrics and qualimetrics: part B. Elsevier, Amsterdam (1998)

Joliffe, T.: Principal components analysis. Springer, New York (1986)

Massart, D.L., Vandeginste, B.G.M., Buydens, L.M.C., De Jong, S., Lewi, P.J., Smeyers-Verbeke, J.: Handbook of chemometrics and qualimetrics: part a. Elsevier, Amsterdam (1997)

Wold, S.: Principal components analysis. Chemomet. Intell. Lab. 2, 37–52 (1987)

Kaufman, L., Rousseeuw, P.J.: Finding groups in data; an Introduction to cluster analysis. Wiley, New York (1990)

Massart, D.L., Kaufman, L.: The interpretation of analytical data by the use of cluster analysis. Wiley, New York (1983)

Noworol, C.: Analiza skupien w badaniach empirycznych. Rozmyte modele hierarchiczne [Cluster analysis in empirical research. Fuzzy hierarchical models]. Panstwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warsaw (1989)

Romesburg, H.C.: Cluster analysis for researchers. Lifetime Learning Publications, Belmont (1984)

Smoliński, A.: Analysis of the impact of physicochemical parameters characterizing coal minewaste on the initialization of self-ignition process with application of cluster analysis. J. Sustain. Min. 13(3), 36–40 (2014)

Smoliński, A.: Gas chromatography as a tool for determining coal chars reactivity in a process of steam gasification. Acta Chromatogr. 20(3), 349–365 (2008)

Hartigan, J.A.: Statistical theory in clustering. J. Classif. 2, 63–76 (1985)

Ward, J.H.: Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58, 236–244 (1963)

Smoliński, A., Stempin, M., Howaniec, N.: Determination of rare earth elements in combustion ashes from selected polish coal mines by wavelength dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. Spectrochim. Acta B. 116, 63–74 (2016)

Smoliński, A., Walczak, B., Einax, J.W.: Hierarchical clustering extended with visual complements of environmental data set. Chemomet. Intell. Lab. 64, 45–54 (2002)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Poland, under Grant No. 10020217.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Smoliński, A., Howaniec, N. Chemometric Modelling of Experimental Data on Co-gasification of Bituminous Coal and Biomass to Hydrogen-Rich Gas. Waste Biomass Valor 8, 1577–1586 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-017-9850-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-017-9850-z